Addressing the Crisis in the Treatment of Osteoporosis: A Path Forward

ABSTRACT

Considerable data and media attention have highlighted a potential “crisis” in the treatment of osteoporosis. Specifically, despite the availability of several effective drugs to prevent fractures, many patients who need pharmacological therapy are either not being prescribed these medications or if prescribed a medication, are simply not taking it. Although there are many reasons for this “gap” in the treatment of osteoporosis, a major factor is physician and patient concerns over the risk of side effects, especially atypical femur fractures (AFFs) related to bisphosphonate (and perhaps other antiresorptive) drug therapy. In this perspective, we review the current state of undertreatment of patients at increased fracture risk and suggest possible short-, intermediate-, and long-term approaches to address patient concerns, specifically those related to AFF risk. We suggest improved patient and physician education on prodromal symptoms, extended femur scans using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to monitor patients on antiresorptive treatment, better identification of high-risk patients perhaps using geometrical parameters from DXA and other risk factors, and more research on pharmacogenomics to identify risk markers. Although not the only impediment to appropriate treatment of osteoporosis, concern over AFFs remains a major issue and one that needs to be resolved for effective dissemination of existing treatments to reduce fracture risk. © 2016 American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Introduction

In a recent perspective,1 we highlighted a potential “crisis” in the treatment of osteoporosis. Specifically, despite remarkable advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis, there is increasing evidence that many patients who should receive pharmacological treatment are either not being offered appropriate medications or are simply not taking these medications. A major reason for this “gap in treatment” appears to be patient concerns over bisphosphonate-related and perhaps other antiresorptive drug-related side effects, including osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and atypical femur fractures (AFFs). This issue was highlighted recently by an article by Gina Kolata in the New York Times titled, “Fearing Rare Side Effects, Millions Take Their Chances with Osteoporosis.”2 In this follow-up perspective, we expand upon the public health impact of osteoporotic fractures, the problem of undertreatment of patients at high risk for these fractures, and propose a potential path forward to address specifically the concerns that patients with osteoporosis have about available treatments that reduce their high risk of fractures.

The Changing Public Health Impact of Osteoporotic Fractures

Osteoporotic fractures lead to substantial morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic impact. Hip fractures, the most devastating of all fractures, are associated with an approximate 25% 1-year mortality rate3 and lead to 65,000 deaths each year in the US alone. More than half of the patients who experience hip fractures are permanently incapacitated and up to 20% spend time in a skilled-care nursing facility.4 Hip fracture survivors who were not in a state of poverty at the time of their event are more than twofold more likely to become destitute after such a fracture.5 The number of women who will experience a fracture in 1 year exceeds the combined number of women who will experience incident breast cancer, myocardial infarction, or stroke across all ethnic groups.6 Fractures also have considerable socioeconomic consequences and lead to an estimated burden on society of $18 billion annually in the US and 36 billion euros in Europe;7, 8 these costs are expected to double by 2050. Patients fear fractures. When hypothetical scenarios of fracture health states were presented to patients at high fracture risk,9 a hip fracture requiring time in a nursing home received a “preference” weighting only slightly better than experiencing binocular blindness, which was only slightly closer to the anchor health state of death.

Until recently, the problem of osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures in particular appeared to be coming under better control, although many factors beyond anti-osteoporosis medication use (eg, changing smoking habits or obesity) may have contributed to this decline. Thus, epidemiologic data from both the US and Canada beginning in the late 1990s and extending through the mid-2000s suggested that age-adjusted rates of hip fractures were declining.10, 11 Similar findings over comparable time periods were found in Denmark and in Belgium, where the decline in hip fractures followed an increase in prescription of osteoporosis therapies.12, 13 An interrupted time series analysis conducted using data from the United Kingdom showed that a reduction in hip fractures followed the release of a generic form of alendronate and a published guidance from the National Institute on Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on osteoporosis management.14 Similar temporal trends were observed in Spain and in other parts of Europe.15

These favorable trends in hip fracture incidence have not, however, been observed consistently in all groups. In the US, for example, not all demographic groups had the same reduction in age-adjusted hip fracture rates that had been observed predominantly among white and Asian women. Among Hispanic Americans and to a lesser degree African Americans, there was either a slight increase or a plateauing of age-standardized hip fracture rates in the late 2000s.16 Of even greater concern, recent examination of US Medicare data showed that past temporal reductions in age-adjusted hip fractures appear to be plateauing in the US starting around 2012.17 In Australia, in the late 2000s, a similar trend and even a slight increase in fracture rates was associated with a temporal decline in bisphosphonate prescriptions.18 It is unclear what has caused these apparent changes in country-specific fracture rates, but there is concern that a decline in testing and treatment for osteoporosis, discussed below, is one potential explanation. Newer data from Sweden and Denmark suggest that this changing fracture pattern is at least partially attributed to period and cohort effects, including changing use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and non-osteoporosis medications that may affect bone, vitamin D supplementation, changing patterns of physical activity, urbanization, greater overall longevity, and the growing obesity epidemic.19 Being cautious of the ecologic fallacy when interpreting such population trends is, of course, necessary, but more investigation into one potential cause, the current and future impact of an almost uniform international decline in osteoporosis testing and treatment, is clearly warranted.

Undertreatment of Patients at High Risk for Osteoporotic Fractures

Studies from the US and from Europe have documented a substantial decrease in the use of bisphosphonates in recent years. Data from the US Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and the National Inpatient Survey demonstrated that after an increase in oral bisphosphonate use between 1996 and 2006, there was a decline of more than 50% between 2008 and 2012.20 In a survey of osteoporosis in the European Union, a similar pattern of bisphosphonate use was observed with an increase between 2001 and 2007–8 followed by a decline in the following 3 years.21 The causes of decreased bisphosphonate use cannot be directly inferred from these studies, although the timing of the onset of declining use, shortly after media reports and FDA announcements about safety concerns, suggests that fear of adverse effects is one factor.20, 22 Other possible contributory factors include more accurate targeting of bisphosphonate therapy to high-risk individuals, appropriate cessation of use after treatment for some years, and/or switching to alternative therapies.

Given the recent decline in bisphosphonate use, a key question is whether this is observed in the highest-risk populations, for example in those who have recently suffered a hip fracture. Such individuals are known to be at high risk of further fractures, including hip fracture,23 and there is wide consensus amongst national guidelines that bone-protective therapy should be prescribed. In a retrospective observational cohort study based on US administrative claims data, Solomon and colleagues24 reported a fall in osteoporosis medication use between 2001 and 2011 in individuals hospitalized for hip fracture, from 40% to 21%, which suggests that the highest-risk populations are, in fact, not receiving appropriate therapy. Factors associated with a reduced likelihood of being prescribed osteoporosis medication after hip fracture included older age and male sex, whereas use of medication prefracture was strongly associated with medication use postfracture.

Undertreatment of patients with hip fracture has also been reported from other parts of the world. In a large cross-national study, Kim and colleagues compared treatment rates after hip fracture in patients from the US, Korea, and Valencia, Spain.25 Six months after fracture, treatment rates in US subjects were less than 20%, whereas somewhat higher, albeit still suboptimal, rates were found in Korean and Spanish subjects (42% and 28%, respectively). There was also a significant trend for decreased use over time of oral bisphosphonates in Korea and Spain. Adherence, defined as the proportion of days covered by prescription in the first year of treatment, was low, ranging between 43% and 70%, thus compounding the problem of undertreatment.

Low treatment rates after incident clinical fracture have also been reported from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW), a prospective observational practice-based study in postmenopausal women from the US, Canada, Europe, and Australia.26 Only 25% of previously treatment-naive women were taking osteoporosis medication after hip fracture; the highest treatment rates were found in women with clinical spine fracture, although still inappropriately low at 42%. Even in women with more than one incident fracture during 1 year of follow-up, only 35% were prescribed bone-protective medication. Baseline calcium use and a baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis were significantly associated with increased use of osteoporosis medications.

Collectively, these data demonstrate an alarming decline in rates at which osteoporosis medications are prescribed, especially among high-risk patients, including those who suffer a hip fracture. Possible causes include underdiagnosis of osteoporosis, concerns about adverse effects, misunderstanding of the benefit/risk ratio, poor coordination of health care systems for fracture patients (eg, lack of fracture liaison services in the US and parts of Europe), and inadequate access to appropriate investigation and treatment.

Potential Solutions to the Problem of Undertreatment of Osteoporosis

Specific approaches to improve appropriate treatment of patients with osteoporosis

As reviewed in the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research task force reports,27, 28 although the relative risk of AFFs in patients taking bisphosphonates is increased, the absolute risk of AFFs in these patients is low, ranging from 3.2 to 50 cases per 100,000 person-years. Even though this risk may rise to as high as ∼100 per 100,000 person-years with long-term (>5 years) use,27 the overall risk of therapy and benefit/risk ratio with these drugs remains extremely favorable for those patients at high fracture risk of common osteoporotic fractures. Despite these reassuring statistics, primary care physician and patient attitudes have been greatly influenced by the media attention given to AFFs. There is pervasive concern among physicians, and particularly among patients, that these fractures may be vastly underreported and are perceived by many patients as a severe and somewhat paradoxical consequence of treatment intended to reduce fracture risk. As the documented decline in osteoporosis treatment demonstrates,20-22 the current approach of trying to familiarize patients with the favorable benefit/risk ratio is simply not working. As such, the challenge is to demonstrate to patients that we have heard their concerns. Key ways to address patient concerns include developing ways to diagnose AFFs before they occur and, over the longer term, to identify those patients who may be at increased risk of this complication even before starting osteoporosis medications.

Table 1 lists potential short-, intermediate-, and long-term approaches to address patient concerns about the risk of AFFs. Better patient and physician education is certainly a key component, including defining as clearly as possible the favorable benefit/risk ratio of bisphosphonates. Indeed, the best estimates are that with bisphosphonate therapy, one would prevent anywhere from 80 to 5000 fragility fractures for every AFF possibly induced by treatment.29 Additionally, patients should be appropriately counseled to recognize the prodromal symptoms of AFF, such as new groin or hip pain, and to report these to their health care provider. One way to do this might be to develop brief, standardized, and simple-to-administer questionnaires for common prodromal symptoms of AFF that could be linked to prescription renewals by physicians. Also on the provider side, appropriate decision-making tools need to be developed to guide physicians and health care providers regarding identifying high-risk patients and when to order follow-up studies, such as femur X-rays or extended femur dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA imaging; see below), particularly in patients who have been on therapy for more than 3 to 5 years.

| Short term |

|

|

| Intermediate term |

|

| Long term |

|

|

|

|

- AFF = atypical femur fracture; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

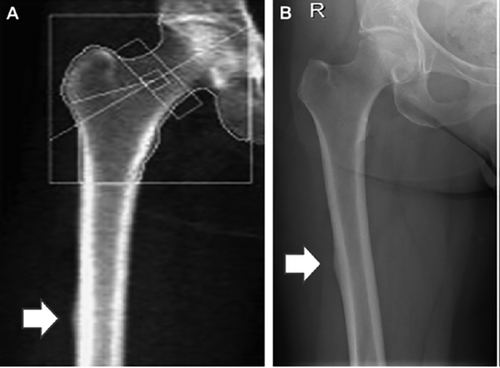

A second short-term approach that could be implemented fairly rapidly is incorporating DXA imaging of the femur in the region where AFFs typically occur to identify potential early signs of an impending AFF. The feasibility of this approach has been demonstrated by McKenna and colleagues,30 who studied 257 patients over the age of 50 years, all of whom had been on bisphosphonate therapy for more than 5 years. Using an extended femur scan at the time of routine DXA (Fig. 1A), they found abnormal DXA images (eg, “flaring” or “beaking” of the cortex) in 19 subjects (7.4%). Follow-up radiographs (Fig. 1B) showed evidence of incomplete AFF in 7 patients (2.7%) (5 with periosteal flare and 2 with a visible fracture line), 7 showed no abnormality, and 5 showed an unrelated radiographic abnormality. It is important to note that although radiographic findings suggestive of AFF were noted in 2.7% of patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy in this convenience sample of patients, population data on clinical AFFs indicate a far lower prevalence, at worst in the range of 0.13% to 0.22%.31 In addition, the majority of patients with radiographic changes consistent with partial or incomplete AFF may not, in fact, progress to clinical AFFs.32 Nonetheless, monitoring patients for such radiographic changes would clearly identify a potentially high-risk subgroup for more extensive imaging and consideration of drug discontinuation as appropriate.

Importantly, Hologic (Bedford, MA, USA) currently offers the option of performing this extended femur scan on its new scanners, and this approach has been approved by the FDA for monitoring AFF risk; GE Lunar (Madison, WI, USA) is in the process of offering a similar option, also recently approved by the FDA, as an update to existing software. Thus, baseline and follow-up “monitoring” scans performed perhaps annually starting 3 to 5 years after the initiation of therapy makes eminent clinical sense, analogous to monitoring liver enzymes for patients on a statin or serum creatinine for patients starting ACE inhibitors. Although providing some measure of reassurance to patients, it would still be important to guard against false reassurance and to emphasize that patients also notify their health care providers regarding onset of symptoms that might signal an AFF.

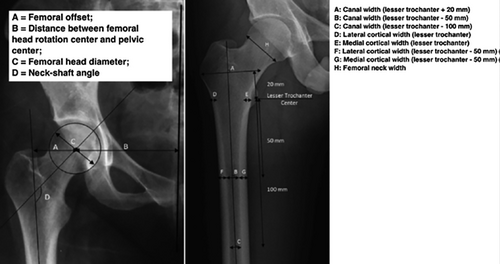

In addition to these short-term approaches, over the intermediate term (Table 1), we need to develop new tools to identify patients at increased AFF risk after treatment. As an example, Mahjoub and colleagues33 compared femur geometrical data (Fig. 2) using AP radiographs of the pelvis in 56 AFF patients versus 112 controls with traumatic or fragility hip fractures. In this analysis, patients with AFF had several geometrical features that distinguished them from controls, including an excessive femoral offset, proximal femur neck angle in varus, and greater proximal cortical thickness. If this approach could be validated in larger cohorts and incorporated into a baseline DXA scan, it may serve to identify a subset of patients in whom either shorter duration of therapy and/or closer follow-up on therapy are warranted. Another potential risk factor for AFF is Asian race. Thus, Lo and colleagues34 noted a high proportion of those with atypical fracture had contralateral femur findings and focal cortical thickening, especially among Asians. The race distribution of atypical fractures differed dramatically from hip fractures in the Kaiser database: hip fractures, whites, 85%; blacks, 3%; Hispanics, 6%; and Asians, 5%. In contrast, the race distribution of atypical femur fractures was whites, 45%; blacks, 0%; Hispanics, 5.3%; and Asians, 50%. Asian women tend to have lower bone mineral density (BMD) and shorter hip axis length, suggesting that femoral biomechanical differences may contribute to the risk of atypical fractures.34 Other risk factors for AFF are remarkably similar to risk factors for typical osteoporotic fractures, including rheumatoid arthritis and >6-month use of glucocorticoids.35

The long-term vision (Table 1) for tackling the AFF problem includes a number of research strategies and stimulation of the new drug pipeline, which has been inexorably declining. On the research side, there has been a suggestion that genetic factors may play a role in conferring risk for AFF, such as the observation noted above that AFFs may occur more in Asian women.34 In fact, a small pilot study using an exome array in 13 patients with AFF and 268 controls identified a greater number of rare variants in the cases compared with the controls. The analyses were restricted to the variants with minor allele frequencies less than 3%, which limited the ability to make meaningful inferences about individual variants. There was no evidence of enrichment of any specific pathways using all of the results.36 At the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Roca-Ayats and colleagues performed whole exome sequencing in three sisters who developed AFFs while taking bisphosphonates and three unrelated AFF cases.37 They found that all three affected sisters harbored a p.Asp188Tyr mutation in the GGPS1 (geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase) gene, which is critical to osteoclast function, and can also be inhibited by bisphosphonates. This study was far too limited in size to have the power to identify genetic risks for AFF, yet provided early evidence that there may be a genetic predisposition to AFF. Ongoing studies are needed that can leverage well-phenotyped cases and controls in sufficient numbers to have the power to detect rare variants associated with AFFs, while not overlooking the possibility that common variants in multiple genes may contribute as well. Also noteworthy is a recent study of DNA methylation changes in bisphosphonate users that might implicate differential gene expression conferred by use of osteoporosis medications. This represents another promising line of research to identify the underlying epigenetic drivers of AFF risk in bisphosphonate users.38

Looking ahead to closing the treatment gap in osteoporosis, one of the most troubling concerns is the lack of new drug development. There is a need to bring new drugs to this growing market. As the average life expectancy increases worldwide, there will be a steady rise in the proportion of the population who are older than 65 years and even 75 years, and thus at risk for osteoporotic fractures, just by virtue of advancing age alone. There will be a need for new osteoporosis drugs that are effective in reducing common fractures, while circumventing the AFF side effect, which has been observed in most drugs with antiresorptive mechanisms. Recent activities provide encouragement for the possibility that drug approval requirements may be changing. The Biomarkers Consortium-Bone Quality Project is attempting to qualify a surrogate marker for fracture prediction that could be used in clinical trials,39 obviating the need for multiple large randomized trials with fracture as an endpoint. If such a surrogate marker is approved for osteoporosis drug development, this will provide a financial incentive to bring new drugs to market.

An additional long-term strategy to close the treatment gap is to better align recommendations and guidelines regarding screening and treatment of patients at risk for fracture. In contrast to guideline development in areas such as hyperlipidemia40 and hypertension,41 which produce regular unified and updated guidelines, osteoporosis guidelines come from a number of different organizations such as the National Osteoporosis Foundation42 and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.43 At least in the US, a single guideline for fracture prevention would help providers follow a well-accepted strategy. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we need much better patient engagement strategies to help build trust with our patients; this is a prerequisite for any approach that would increase treatment rates for those patients at high fracture risk.

An external assessment of osteoporosis management and research

The American Society for Bone and Mineral Research and its members have been very fortunate to have decades of strong support for basic and clinical research efforts by NIH from multiple Institutes. At a fiscal level, this has led to support for randomized trials, larger observational cohort studies, and novel high-risk, high-impact proposals, as well as bench studies that in some cases have the potential to translate to the bedside. For the most part, these efforts have paid substantial dividends with respect to osteoporosis medications. More recently, attention at the federal level has focused on patient-specific outcomes as primary endpoints for diseases of the musculoskeletal system. For example, numerous tools have been developed to measure individual aspects of disease progression as well as the impact of treatment. But surprisingly, we have few measures that provide insight into how patients view current treatment modalities for osteoporosis, nor how much risk an individual is willing to tolerate for adherence to these agents. Fortunately, NIH has been quick to recognize the enormity of the problem and is committed to providing several possible long-term approaches in collaboration with clinician-scientists in our field. The most compelling is the potential investment into a systematic review of the scientific basis for current osteoporosis treatments, both in terms of benefits and risks, through the Office of Disease Prevention. This effort could ultimately lead to a greater scientific consensus while at the same time incorporating the fundamental importance of patient perspectives into future algorithms. NIH can also promote the development of tools that clinicians can use to gauge patient knowledge and willingness to adhere to anti-osteoporosis therapies. Undoubtedly, both short- and long-term efforts in collaboration with NIH will be necessary at several levels to address this urgent problem.

Although this perspective is focused principally on patient and physician concerns over AFFs, fear of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) also represents a significant barrier to treatment. Although rare in people treated for osteoporosis with bisphosphonates, with an estimated incidence of only 0.001% to 0.01%,44 reports of its occurrence and the associated media exposure have created significant concerns among patients, physicians, and dental practitioners. As with AFFs, there is a need to communicate more clearly to patients and their physicians and dentists the rarity of ONJ and the positive benefit/risk balance of bisphosphonate therapy in people at high risk of fracture. In addition, because dental disease is a major risk factor for the development of ONJ, taking measures to maintain good oral hygiene and dental health can further minimize the chances of developing this rare adverse effect.

Summary and Conclusions

In this perspective, we have highlighted increasing evidence that decades of progress in finding new treatments for osteoporosis could be undone by patient and physician fears over the risk of AFFs related to long-term bisphosphonate (and perhaps other antiresorptive drug) treatment. Although nonpharmacological measures such as fall prevention, increased physical activity, and home-safety interventions are important components of a fracture prevention program, pharmacological treatment is clearly indicated for many patients, and fear of AFFs is preventing these patients both from being prescribed osteoporosis medications and from taking such medications even if prescribed. Indeed, although there is debate over the use of bisphosphonates or other osteoporosis drugs for primary prevention of fractures in lower-risk individuals,45 there is agreement that high-risk individuals, particularly those with a previous history of fragility fractures, benefit from pharmacological therapy.46 Although we need to continue to stress the favorable benefit/risk ratio of osteoporosis treatments in the patients who truly need pharmacological therapy, quoting relevant statistics to patients is not sufficient to allay their concerns. As a community of “experts” in osteoporosis, we need a focused, concerted, and effective effort to alleviate patient concerns. In this perspective, we have attempted to outline a possible path forward to addressing this important problem for our field and for our patients.

Disclosures

SK, JAC, CR, and JC state that they have no conflicts of interest. DPK has received royalties from Springer for editing a book on osteoporosis, royalties from Wolters Kluwer for UpToDate, and a grant to his institution from Merck. He has also served on a Scientific Advisory Board for Merck. His institution has received grant funding from Policy Analysis, Inc. KGS has served as a consultant to Amgen, Merck, and Radius. ES has received research support to her institution from Lilly and Amgen for studies related to idiopathic osteoporosis in premenopausal women and from Merck for studies of high-resolution imaging of bone microarchitecture.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Joan McGowan and Ms Ann Elderkin for helpful comments and suggestions.

Authors’ roles: All authors were involved in drafting and reviewing this manuscript.