How to choose a craniotomy for the intracranial foreign bodies when the airway was occupied: a case report

Abstract

Background

Intracranial foreign bodies caused by trauma are rare in clinical emergency cases. Similar reports in the past pay less attention to establish artificial ventilation for these patients for the following anesthesia and surgery.

Case information

We reported a 3-year-old boy who suffered from oral penetration of the cerebellum from the skull base by a chopstick after a fall. To avoid pediatric tracheotomy, we conducted a reconstruction analysis by spiral CT scan and found a transnasal tracheal intubation pathway allowing the endotracheal tube through, successfully established artificial ventilation, and smoothly implemented the removal surgery of foreign bodies under general anesthesia. The child was cured and discharged without surgical complications or sequelae during the follow-up.

Conclusion

Imaging technology plays an important role in determining airway during endotracheal intubation.

Introduction

The intracranial foreign body injuries are a common type of injury in wartime medical treatment and has a high proportion of occurrence (Alvis-Miranda HR, et al., 2016; Pilipenko G, et al., 2020), but are rare disease in civilian health care. The human brain is protected by the rugged skull, but some special intracranial traumas could be caused by penetrating the external auditory canal (Charlton A, et al., 2019), orbital cavity (Yoshihara S, et al., 2019), sinuses, and skull base (Wen YH, et al., 2017), thus causing intracranial foreign bodies, which is determined by the anatomical characteristics of vertebrates. Due to the special cranial approach, such injuries are closely related to the distribution of blood vessels and nerves, even resulting in more serious consequences than the simple cranial injury. Therefore, once a patient is diagnosed, the foreign body must be removed as early as possible to avoid complications or secondary injuries from displacement (Brawanski N, et al., 2016; Rahimizadeh A, 2019). We report a case of anesthesia in a child with an intracranial foreign body. Moreover, the path of endotracheal intubation can be quickly determined by CT scan so that the artificial airway can be quickly established and emergency surgery can be carried out in time. A case of patient with intracranial foreign bodies when the airway was occupied in our hospital, which is reported as follows.

Case presentation

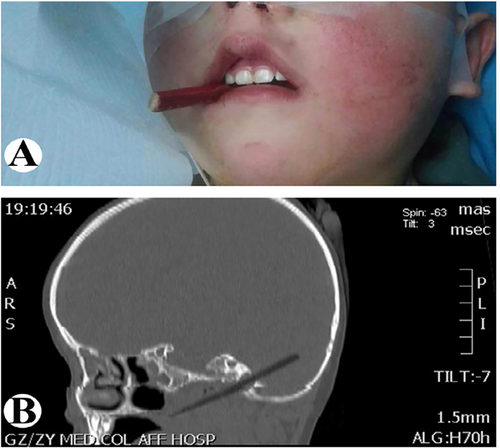

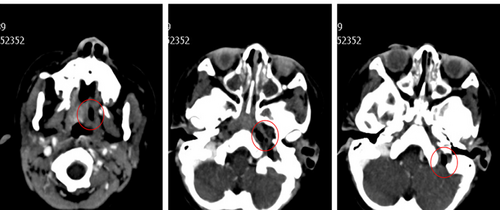

A 3-year-old boy whom weight 17 kg had suffered from oral penetration of a chopstick after a fall at lunch for 8 hours. Physical examination showed trismus and biting the chopstick, which was exposed 5 cm out of the incisors (Figure 1). GCS15 showed voluntary opening eyes, correct verbal exchanges, and activities as requested. There was a small amount of blood in the oral cavity but without active bleeding. Laboratory tests showed no abnormalities. Cranial CT was diagnosed as foreign bodies in the left posterior fossa (Figure 1). We hypothesized that the path of endotracheal intubation could be evaluated by imaging. However, we are concerned that MRI may increase foreign body displacement in this patient with transport. Therefore, we performed another enhanced spiral CT scan and analyzed the endotracheal intubation path and maximum intensity projection (MIP). Foreign bodies were across the oral cavity with a left nasal opening (Figure 2), insignificantly oppressing the deep cervical vein at the end of the left sigmoid sinus (Figure 2) and passing through the jugular foramen into the left cerebellar hemisphere (Figure 2). The opening of the right nasal passage was complete, between which and the glottis, there was a space through the endotracheal tube.

CT images of intracranial foreign bodies. (A) Trismus and biting the chopstick, which was exposed 5 cm out of the incisors. (B) Computed Tomography was diagnosed as foreign bodies in the left posterior fossa.

Images of enhanced spiral CT scan. (A) Foreign bodies were across the oral cavity with a left nasal opening. (B) Insignificantly oppressing the deep cervical vein at the end of the left sigmoid sinus, and (C) passing through the jugular foramen into the left cerebellar hemisphere.

Preoperatively, the emergency tracheal incision equipment was prepared and a 4.5 F reinforced endotracheal tube was selected to wrap the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope for endotracheal intubation (Pentax FI-9BS) (Figure 3). After successful anesthesia with sevoflurane in oxygen, the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope was inserted into the right nasal cavity for exploration of the oral and pharyngeal cavities. There was a suitable space for endotracheal tube between the opening of the right nasal passage and the glottal so that the endotracheal tube would go through without touching the chopstick. Then the endotracheal tube was inserted into the glottis keeping away from the chopstick. After successful intubation, the end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) detector was connected. When the CO2 waveform was detected, immediate intravenous injection of intravenous anesthetics and muscle relaxants was given for maintaining intravenous anesthesia, and the anesthesia machine was connected for manual mechanical ventilation.

The flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope for endotracheal intubation (Pentax FI-9BS).

Under the microscope, the foreign bodies' position into the cranium was fully exposed, and a 20 cm foreign body was pulled out from the oral cavity, which was into the cranium for 3 cm. The duration of surgery lasted 129 minutes, and the intraoperative blood loss was 150 ml. The boy was sent back to neurosurgical ICU, and the endotracheal tube was removed after six hours, without active bleeding and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid in the oral cavity. Antibiotics were used to prevent intracranial infection during and three days after the operation. The hospital stay was 22 days, and the postoperative 3-month review showed good intracranial recovery and healthy physical, without complications.

Discussion

After reviewed, regrettably all literature reported in the past 30 years (1990-2020), we found only a few reports that described whether the difficulties were encountered during anesthesia of these patients. Among these reports, just one case concerned the difficult airway caused by an intracranial foreign body, which was not implemented the craniotomy (Zou W, et al., 2009). However, in the case of being unable to move the foreign body and even open mouth, the conventional identification of airway was meaningless (Loftus PA, et al., 2014). Since the rear opening of the nasal passage might be blocked by the foreign body, blind attempts of transnasal endotracheal intubation could cause disastrous consequences (Schwarz D, et al., 2015). Preoperative tracheostomy and establishment of reliable airway management were relatively safe. However, the tracheotomy was not included in the removal surgery of the intracranial foreign body just as a helpless choice. If this way was selected to establish the airway, the possible consequences must be accepted, such as long-term carrying with the tube, wound hemorrhage, pneumothorax, mediastinal emphysema, tracheal stenosis, and requested tracheal reconstruction after many years (D'Souza JN, et al., 2016). Currently, there were no authoritative guidelines to explain such cases on how to establish the artificial ventilation. Therefore, any anesthesiologist in charge of such patients would face a huge challenge. Despite the special condition of injury in this case that a chopstick was coincidentally inserted into the cerebellum through the jugular foramen, the injured boy would have the opportunity to be healed if the foreign body could be successfully removed. Therefore, the possibility of general endotracheal intubation was of great significance for this patient. It was not emphasized that such cases must be given endotracheal intubation instead of tracheotomy. However, the successful experiences of this case reminded us that the role of imaging techniques in helping to determine the airway could not be ignored. If the endotracheal intubation was a better choice, CT scan, ultrasound examination and other uncommon items might provide a great help for our analysis and airway management and even reverse the whole situation.

Ethical statement

All the experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (No. KKL-2020-311).

Consent to participate

Written consent was signed for all the patients of aged 18 years or above. For patients under 18, a legal guardian or parent signed the consent form.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest were declared.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 81660193.

Transparency statement

The authors affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Authors' contribution

Liu-De Xing delivered the main conception, drafted the work and approved the final version; Juan Li assisted with recording data; Dan Wen, Fan Zhang and Yu-Hang Zhu supported the work with multiple files.