Does Chinese policy banks' overseas lending favor Belt Road Initiative countries?

Abstract

This paper examines how Chinese policy banks responded to China's Belt Road Initiative (BRI) using transaction-level international syndicated loan data. Employing a difference-in-differences (DID) estimation, we show that Chinese policy banks increased aggregate lending (number of loans and loan amounts) to firms from the BRI countries compared to those from the non-BRI countries after the initiative. This increase was more pronounced among firms along the continental route and in the infrastructure sectors. We also find that Chinese policy banks' loans to the BRI borrowers were associated with reduced spread, lowered collateral requirement, and extended maturity. Moreover, our results suggest that Chinese policy banks gave more support to firms from the BRI countries with weaker economic performance, more fragile institutional quality, and closer political interests. Overall, our study highlights the supportive role played by Chinese policy banks in implementing a national globalization strategy.

1 INTRODUCTION

A significant but controversial debate in the banking sector is the impact of policy lending on a state-owned bank's loan performance. State-owned banks in developing countries have been found to serve political motives other than profit-maximization goals (Berger et al., 2004; Berger, 2007; Dinc, 2005). For instance, in Brazil, lending from government banks was politically targeted (Coleman & Feler, 2015). In a similar vein, recent studies suggest that Chinese state-owned banks are directed to support low-performing firms with credits (Bailey et al., 2011; Podpiera, 2006). Also, China's overseas lending is unsurprisingly guided by its foreign policies (Dreher & Fuchs, 2016; Dreher et al., 2018).

The past two decades have seen China demonstrating growing importance as a fund provider to the developing world (Horn et al., 2021). Following the “going global” strategy and the focus on “win–win” cooperation, China's state-to-state lending emphasizes the linkages between aid, trade, and investment, and its form of finance has expanded from aid and grants to preferential loans and joint ventures (Brautigam, 2009; Dreher & Fuchs, 2016). It is thus intriguing to investigate China's state-level commercial lending under the grand Belt Road Initiative (BRI), as this kind of large-scale globalization strategy is rare in other countries.

To financially support the BRI, China has been distributing substantial investments to BRI-related projects through outbound direct investment (ODI), bilateral funds, and commercial bank loans (Devonshire-Ellis, 2019). Existing studies on the BRI have touched upon China's outward direct investments and outbound state-to-state lending (Du & Zhang, 2018; Du et al., 2021; Liao et al., 2020; Sun & Liu, 2019). To our best knowledge, there are no prior studies that formally explore China's official response to the BRI countries from the perspective of corporate commercial loans. Thus, a natural question is how Chinese lenders, especially the policy banks, responded to the national strategy in the international commercial loan market.

This study aims to investigate the pattern of firm-level syndicated loans from Chinese policy banks at both the country-aggregated and the deal levels.1 We focus on policy banks since they are strongly motivated to echo the BRI and thus may present different lending behaviors relative to nonpolicy banks.2 More specifically, the policy banks in China are state-owned while they have a distinct lending purpose compared to nonpolicy state-owned banks. The establishment of policy banks aims at relieving the nonpolicy state-owned banks' financing constraints so that they can perform commercially in China. In other words, Chinese policy banks are responsible for directing loans to long-term projects such as infrastructure in comparison to other nonpolicy banks (including state-owned and private banks).3

Employing a difference-in-differences (DID) estimation strategy, we find the empirical results that loans from Chinese policy banks are more likely to flow to firms in the BRI countries with preferential loan terms. Specifically, the aggregate-level loan deals and amounts on average increased by 31 percentage points and 177 folds, respectively. Those loans favor companies in countries along the continental route and in the infrastructure industries among the BRI participants. The deal-level results show that, compared with the non-BRI borrowers, the BRI borrowers faced a 57-percentage-point drop in loan spread, a 52% decrease in the probability of secured loans, and an 85-percentage-point increase in maturity.

We also conduct a series of additional tests using alternative samples and specifications to confirm the robustness of our findings. First, we find that our DID estimates pass the parallel trend test and are sensitive to the falsified policy initiation year if we change the policy shock year from 2013 to 2011. Second, we re-estimate our baseline model using alternative samples with only non-Chinese borrowers or non-Chinese lenders, finding unchanged main results. Last, we show that our baseline results are robust to alternative policy treatment status by using the corresponding year of signing the BRI agreement.

To understand the potential mechanisms that shape the findings, we consider three possible economic channels based on borrower countries' characteristics: economic performance, institutional quality, and political stability. The estimates for the channel variables suggest that Chinese policy banks provide more credit support to companies in countries with weaker economic performance, lower institutional quality, and closer political relations.

This study distinguishes the existing literature from the following strands. First, recent works primarily focus on the economic impacts of the BRI, such as cross-border trade and investments (Du & Zhang, 2018; Gallagher & Irwin, 2014; Liao et al., 2020; Sun & Liu, 2019), national-level lending (Du et al., 2021), and Fintech household borrowing responses (Zhang et al., 2022). We are among the first to provide firm-level evidence on international lending by Chinese policy banks.

Second, studies on China's overseas lending concern state-to-state lending from China to developing countries, mainly in the aid form (Dreher & Fuchs, 2016; Dreher et al., 2018). This literature finds that loans from China tend to have economic, institutional, and political preferences. We contribute to the literature by revisiting China's overseas lending from the perspective of corporate commercial loans and investigating potential driving factors in the BRI context.

Third, our study relates to the worldwide policy-driven nature of state-owned banks. Prior works find that the lending of government-owned banks often complies with policies (Bailey et al., 2011; Coleman & Feler, 2015; Podpiera, 2006). We provide new evidence on how national strategies affect Chinese policy banks' overseas lending activities using a quasi-natural experiment setting, thereby expanding our understanding of state share and political affiliation effects on banks' behavior.

Last, this study complements the syndicated loan literature on cross-border syndicated lending pricing and nonpricing terms (Chan et al., 2015; Gonas et al., 2004; Haselmann & Wachtel, 2011). Specifically, our work relates to the discussion on how state ownership and government support affect the policy banks' cross-border syndicated lending (Gadanecz et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2017). We generate novel empirical insights by examining Chinese state-owned policy banks' international syndicated lending through the lens of BRI.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the background, and Section 3 discusses the related literature and hypotheses development. Section 4 describes the data sources and summary statistics. Section 5 presents our research design and the main results. Section 6 examines the heterogeneous analysis, and Section 7 checks the robustness of the findings. Conclusion remarks are made in Section 8.

2 INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

2.1 The Belt Road Initiative

BRI is a long-term international project of China's integration into the global economy. Aiming at deepening infrastructure and trade linkage around the globe, BRI encompasses six main economic corridors: Eurasia Land Bridge, China–Mongolia–Russia, China–Central Asia–West Asia, China–Indo-China Peninsula, China–Pakistan, and Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar. The initiative focuses on both land and sea connectivity. Specifically, the Silk Road Economic Belt was put forward by President Xi in autumn 2013 during his visit to Kazakhstan, linking China with South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean through the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea. The other is the New Maritime Silk Road which starts from China's coast and reaches Europe and East Africa through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. According to Huang (2016), BRI covers more than 60 emerging market economies with 64% of the global population and 30% of the world's total output. Therefore, the BRI provides enormous potential for China's economic integration and development.

2.2 Chinese banking sector reform and policy bank

The Chinese government launched comprehensive banking reforms to commercialize the traditional state-owned banks in the 1990s (Park & Sehrt, 2001). The four state-owned banks (including the Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, the Agricultural Bank of China, and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China) have been transformed into market-functioning and profit-oriented institutions (García-Herrero et al., 2009). In other words, the reforms separated the commercial lending and policy lending of the four big banks and further introduced three state-owned policy banks: Agricultural Development Bank of China (ADBC), China Development Bank (CDB), and Export-Import Bank of China (EIBC). In line with the national and regional strategy, policy banks are state-owned and mainly involved with policy-related lending and infrastructure financing.

Each policy bank is dedicated to a distinct lending purpose. In particular, ADBC offers loans to government projects related to agriculture and rural areas in China. CDB raises funds for large investment projects such as infrastructure, energy, and transportation. EIBC specializes in trade financing, which benefits Chinese exports and technologically advanced machinery and equipment imports. Thus, most funding for the BRI projects is primarily raised from Chinese policy banks.

2.3 The international syndicated loan market

The international syndicated loan market is an ideal platform for our research since it is a relatively open cross-border market and is relatively free of national features (Gadanecz, 2004). A borrower in this market can receive loans from either or both the domestic and foreign banks. The granular loan data records detailed information on contracts, including date, amount, borrower and lender characteristics, maturity, interest rate, and so forth. Syndicated lending has become a major international financial instrument that allows risk sharing in the last two decades. Early in 2007, the international syndicated loan market volume reached 3.4 trillion US dollars and took up one-third of global funds (Thomson Financial, 2007). By the end of 2016, the outstanding syndicated loan by Chinese banks had hit 919.4 billion US dollars, which was 11.35% of the total corporate loans in China (Wang et al., 2017).

3 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

A burgeoning literature shows that loans from Chinese state-owned banks often comply with national policies. For instance, Podpiera (2006) finds that Chinese state-owned commercial banks provide more credit support to provinces with lower enterprise profitability. Bailey et al. (2011) conclude that Chinese state-owned banks supply policy loans to keep low-performing firms afloat. Moreover, Gallagher and Irwin (2014) find that project-level ODI loans from Chinese state-owned lenders (i.e., banks) under the “going global strategy” are with subsidized interest rates, which implies that those banks' lending decisions are primarily policy-driven.

In the international syndicated loan market, state-supported banks' behavior is also different from the other participant lenders. Gadanecz et al. (2008) show that banks with state support in explicit or implicit guarantees are associated with lower syndicated loan pricing. The effect is more substantial when the state has higher significant bank ownership. To illustrate, Wang et al. (2017) investigate Chinese banks' cross-border syndicated lending characteristics and find that banks with more state ownership tend to lend to developing countries.

The situation is especially relevant for Chinese state-owned policy banks directly supported by the state under the BRI. As those official lenders incorporate the national interest of gaining China's sustainable access to global trade and investment opportunities (Kaplan, 2016), their syndicated lending is likely motivated by this grand national policy. On top of political motives, borrowers' identity as BRI participants may effectively reduce the cultural and political distance with Chinese state-linked lenders, leading to more preferential loan terms (Giannetti & Yafeh, 2012; Mian, 2006).

Furthermore, the defining feature of the BRI is the infrastructure-led integration plan, which indicates that the initiative aims at win-win goals, as most of the BRI participants are developing countries with inadequate infrastructure facilities. In Asian developing economies, the demand for infrastructure investment is estimated to hit 8 trillion US dollars by 2020, which is mostly not met by the existing multilateral and regional development financing institutions (Asian Development Bank Institute, 2009; Bhattacharyay, 2012). The implementation of BRI is expected to ease the bottleneck for global connectivity—transportation costs by improving the construction of transport infrastructure. Compared with the maritime route (i.e., the Maritime Silk Road), the continental route (i.e., the Silk Road Economic Belt) focuses on transportation infrastructure constructions (Herrero & Xu, 2017). China's emphasis on infrastructure construction and interconnectivity benefits both borrowers and lenders.

On the one hand, participating countries could gain considerable financing through company-level loans to help narrow their infrastructure investment gaps. On the other hand, China benefits by expanding its trade networks and relieving the under-employed domestic industries (Dollar, 2016). Therefore, Chinese policy banks may lend more to countries along the continental route among the BRI participants. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H1.Relative to nonpolicy banks, Chinese policy banks prefer borrowers in the BRI participant countries, especially those along the continental route and in the infrastructure sectors.

Chinese financing is in the form of patient capital that could forgo short-term returns in hopes of substantial benefits from long-term relationships (Kaplan, 2016). It emphasizes infrastructure and heavy industries that could speed up economic growth (Gallagher et al., 2012). By meeting the needs of developing countries, China could secure future commercial contracts (Dreher et al., 2018; Kaplan, 2016).

This approach's rationale is that the government's implicit guarantee backs loans by Chinese state-owned policy banks once the borrowers have trouble with loan repayments (Kaplan, 2016). Consequently, state-owned policy banks are willing to undertake national strategies and endure market volatility to establish long-term relationships with companies in developing countries, especially under the connectivity goal of BRI. It could imply China's long-term ambition for a commercial position in the global marketplace. Owning to this distinct patient capital characteristic, those policy banks are more likely to forgo the market financing criteria and prefer companies in BRI countries with development gaps and potentials. Thus, we posit the second hypothesis:

H2.Relative to nonpolicy banks, Chinese policy banks show more support to BRI borrowers with weaker economic performance.

Besides the development needs, the quality of institutions in the borrower countries might also matter in the international lending market (Dreher & Fuchs, 2016). Hainz and Kleimeier (2012) find that development banks are more likely to participate in loan contracts originated from risky institutional environments since their presence in the contract can mitigate the political risk. Under patient capital characteristics, the lending of Chinese state-owned policy banks may not apply the conventional risk evaluation method but focus more on the connectivity objective of BRI. Moreover, compared with nonpolicy banks, Chinese policy banks under the government's implicit guarantee tend to endure high risk in borrower countries and serve national interests in the wake of the BRI. Our third hypothesis is as follows:

H3.Relative to nonpolicy banks, Chinese policy banks direct more loans to BRI borrowers with poorer institutional quality.

Moreover, China's overseas lending is closely linked to political interests. In developing countries where China operates as a primary lender, high levels of foreign policy alignment are observed in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting similarity and the recognition of the One-China policy (Dreher & Fuchs, 2016; Dreher et al., 2018). The connectivity goal of BRI stresses the importance of forming a close partnership with participant countries. Apart from the tangible infrastructure channel, strengthening the relationship with politically like-minded countries could be an intangible channel to achieve the goal. Hence, Chinese state-owned policy banks may use increased loan amounts and preferential terms to reward the BRI participants' political friendship. Relative to nonpolicy banks, Chinese state-owned policy banks are politically sensitive and may prefer borrower companies in countries that are politically close to China. Thus, we derive our final hypothesis:

H4.Relative to nonpolicy banks, Chinese policy banks favor BRI borrowers with close political interests.

4 DATA, SAMPLE, AND SUMMARY STATISTICS

4.1 Data sources and variable construction

Our aggregate-level dependent variables are the country-year-aggregated number of syndicated loan deals and total amounts (in natural logarithm). For the deal-level analysis, we use the three main outcome variables: (1) spread, (2) whether the loan is secured or not, and (3) maturity. The syndicated loan data are obtained from the Thomson Reuters Loan Pricing Corporation Dealscan database (LPC Dealscan), commonly used in recent loan literature (Ashraf & Shen, 2019; Chan et al., 2015; Keil & Müller, 2020). Dealscan gathers data from borrowers' Securities and Exchange Commission filings, research from banks, and other reliable public sources. It contains detailed and updated documentation on commercial syndicated loan contracts, including pricing (spread) and nonpricing terms (amount, maturity, collaterals, etc.). The database also includes characteristics of borrowers and lenders, such as company names, locations, and industries. Each loan has a unique identifier, and Dealscan records loan-level information such as loan purpose, start and end dates, and so forth.

Our moderating variables include (1) economic performance, (2) institutional quality, and (3) political relations. We measure the economic performance by the 4-year average GDP before the BRI (in natural logarithm). We retrieve data on institutional quality from the World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) for heterogeneous analysis. The WGI consists of six dimensions of governance: voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law, and control of corruption. As to the political relations, we obtain the UNGA voting data and measure the state preferences over foreign policy by the voting similarity score. Following Bailey et al. (2017), the UN voting similarity score is estimated by a spatial model that shows how states translate their preferences into votes. Bailey et al. (2017) use the Metropolis–Hasting/Gibbs sampler to estimate the model parameters. A higher similarity score indicates more common interests (thus better relations). In addition, we also collect the country-level economic data from the Penn World Table 9.1 (Feenstra et al., 2015) for the control variables, covering countries' income level, input, output, and productivity.

Next, we follow Du and Zhang (2018) to construct the belt-road country list. As BRI coverage is constantly expanding, we verify the list according to the official news on each country's most recent participation in the BRI and record the year of signing the agreement. We identify 28 countries as BRI participants among 54 countries in our sample size, with 14 on the land belt and 14 on the sea road.4

4.2 Sample selection

Our sample selection criterion is as follows. The initial deal-level sample is merged from three separate Dealscan data: loan facility, loan pricing, and company information. We exclude companies located in tax havens (Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, and Jersey) as firms' use of tax haven subsidiaries may affect loan terms (Richardson et al., 2020) and contaminate the results. We also exclude Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, following Du and Zhang (2018). To investigate the response of Chinese official lenders in the wake of BRI, we exclude all foreign lender banks located in China from the entire sample based on their names and public information. Moreover, we identify domestic (Chinese) borrower companies located in foreign countries according to the shareholding structure5 and then exclude those identified Chinese borrowers from the initial sample to ensure the robustness of our findings.6 To gauge the policy impact of BRI on loan flows to the real economy, we further exclude borrowers from the financial sectors. We construct the country pair-year loan data by aggregating the deal-level data based on the borrower–lender country pair.

Corresponding to our hypotheses, we construct separate subsamples of Chinese policy and nonpolicy banks; borrowers on the continental and maritime routes. We also construct two samples by dividing the deal-level borrowers into the infrastructure or noninfrastructure sectors and aggregating them based on borrower–lender country pairs.7

4.3 Summary statistics

The summary statistics for all the variables are reported in Table 1 at both country aggregated (Panel A) and deal levels (Panel B), respectively.8 The average number of overseas lending deals granted by Chinese policy banks is 2.39 per year and the average loan amount is about USD 0.089 billion. During the sample periods, the GDP for the sample countries averages USD 1097 billion, with a mean score of 1.152 in institutional quality and 2.565 in voting similarity.9 At the deal level, the average loan spread imposed by a Chinese lender to borrowers is 2.869 basis points, with around 72.8% of deals secured by collaterals and an average maturity of 64.84 months.

| Variables | Observations | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Aggregate level | |||||

| No. of deals | 378 | 2.394 | 1.284 | 0.000 | 15 |

| Aggregate amount (billion) | 378 | 0.089 | 0.288 | 0.000 | 0.383 |

| Avg. GDP (billion) | 378 | 1097 | 2303.736 | 12.13 | 19,485 |

| Avg. WGI | 378 | 1.152 | 0.512 | −1.388 | 1.856 |

| Avg. UN voting | 378 | 2.565 | 1.0174 | 0.040 | 3.361 |

| Creditworthiness | 378 | 56.659 | 43.927 | 0.498 | 255.311 |

| Panel B: Deal level | |||||

| Spread | 197 | 2.869 | 1.419 | 0.750 | 8.000 |

| Whether secured | 151 | 0.728 | 0.325 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Maturity (log) | 169 | 4.172 | 0.772 | 1.946 | 5.485 |

- Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; UN, United Nations; WGI, Worldwide Governance Indicators.

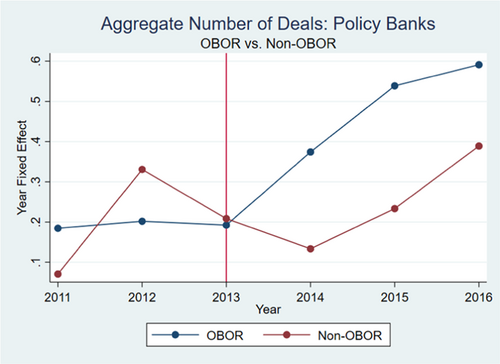

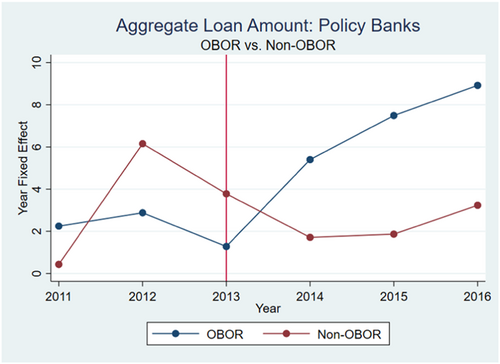

Figures 1 and 2 plot the development of the Chinese policy bank's aggregate loan number and amount along the BRI. To construct the average developing trend, we follow the strategy of Schularick and Alan (2012) to estimate the fixed country-year effects regressions and present the estimated year effects. Starting from 2013, BRI participants show continuous loan growth relative to the nonparticipants, both in the deal number and amount.

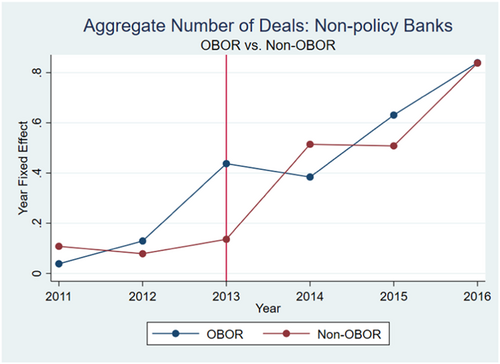

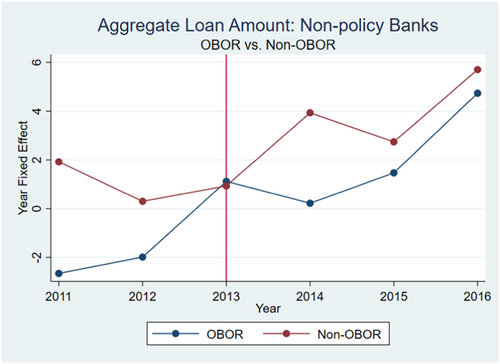

Figures 3 and 4 present the aggregate lending of Chinese nonpolicy banks along the BRI. A slight divergence in the evolution of BRI and non-BRI loans occurs after 2013. Compared with the lending flow of state-owned policy banks in Figures 1 and 2, the loan flow of nonpolicy banks presents a different pattern, where non-BRI participants seem to have similar or even greater borrowing power than BRI participants. Three years after the initiative, the two groups roughly remain at the same level.

The graphical analysis shows that under the backdrop of BRI, loans from Chinese policy banks favor countries along the BRI route. In contrast, Chinese nonpolicy banks are indifferent between BRI and non-BRI countries. To draw more rigorous conclusions, we further conduct a formal regression analysis to examine the lending activities of Chinese policy banks relative to nonpolicy banks towards BRI borrowers after the BRI.

5 RESEARCH DESIGN AND MAIN RESULTS

5.1 Aggregate level: Loan volume

5.2 Deal level: Loan characteristics

5.3 Main results

Table 2 reports the DID estimation results of our main analysis. At the aggregate country level, Chinese policy banks increase significantly more loan deals and aggregate loan amounts to the BRI countries than to the non-BRI countries, as shown in columns (1) and (2) of panel A. The number of loan deals and the loan amount increased by 31% and 177 folds, respectively, compared with the loans to non-BRI countries after the initiative.

| Aggregate | Deal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.268*** | 5.181*** | −0.569** | −0.515** | 0.617** |

| (0.098) | (1.787) | (0.236) | (0.220) | (0.264) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Panel B: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.227** | 4.130** | −0.742** | −0.892** | 2.946*** |

| (0.0972) | (1.670) | (0.305) | (0.357) | (0.480) | |

| Observations | 150 | 150 | 58 | 51 | 41 |

| Panel C: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.336** | 8.904*** | −0.890*** | −0.354*** | 0.770*** |

| (0.146) | (2.771) | (0.133) | (0.010) | (0.090) | |

| Observations | 174 | 174 | 75 | 56 | 40 |

| Panel D: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.160 | −1.626 | −0.318 | 0.010 | 1.149 |

| (0.160) | (2.151) | (0.304) | (0.186) | (0.699) | |

| Observations | 228 | 228 | 139 | 95 | 129 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel E: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.196 | 1.852 | −0.256 | 0.143* | −0.152*** |

| (0.132) | (1.979) | (0.240) | (0.083) | (0.044) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Panel F: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.244 | 2.175 | 0.877 | −0.0767 | −0.280** |

| (0.263) | (3.235) | (0.689) | (0.248) | (0.121) | |

| Observations | 204 | 204 | 198 | 351 | 299 |

| Panel G: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.0740 | 0.750 | 0.870** | 0.169 | 0.235 |

| (0.143) | (1.955) | (0.411) | (0.171) | (0.182) | |

| Observations | 294 | 294 | 221 | 335 | 333 |

| Panel H: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.200 | 2.853 | −0.133 | 0.155* | −0.199*** |

| (0.141) | (1.903) | (0.248) | (0.082) | (0.065) | |

| Observations | 366 | 366 | 1722 | 857 | 2731 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table shows the impact of BRI on Chinese policy banks' overseas lending responses to firms from BRI countries. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results based on Equation (1) and Columns (3)–(5) are at the deal level based on Equation (2). Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

For the deal-level analysis, the full sample results in Columns (3)–(5) of Panel A capture a supportive gesture of Chinese policy banks in reducing the financing costs of borrowers and the effects are economically and statistically significant. Compared with non-BRI borrowers, BRI borrowers experienced 57 percentage points drop in loan spread, a 52% decrease in the probability of secured loans, and 85 percentage points increase in maturity. The above results extend the findings of Gadanecz et al. (2008) that banks' lending behavior in the international syndicated loan market is affected by government support and banks' state-ownership is associated with low loan spreads.

Next, we examine subsample impacts on the lending activities from Chinese policy banks: borrowers along the continental route or the maritime route. Panel B of Table 2 shows the lending responses of Chinese policy banks towards borrowers along the continental route at both country aggregated level and deal level after the BRI implementation. The aggregate-level results in Columns (1) and (2) find that loans from Chinese policy banks primarily flew to countries along the continental route, both from intensive and extensive margins. Regarding the economic magnitude, the number of loan deals and the loan amount on average raised by 25.5% and 61 times. Furthermore, we find loans to firms in those segments would have preferential terms concerning reduced spread (74 percentage points), less collateral (89 percentage points), and extended maturity (18 folds), as shown in Panel B of Columns (3)–(5).

In Panels C and D, we compare the different lending responses of the Chinese policy banks in the wake of BRI for the borrowers in the infrastructure sectors and noninfrastructure ones separately. As reported in Columns (1)–(2) of Panel C, Chinese policy banks prefer BRI participants in the infrastructure sectors with more aggregated deals and amounts after the policy shock, relative to the nonpolicy banks.

Our findings could be justified by the financing needs of large-scale infrastructure projects in the land-belt countries (Cerutti & Zhou, 2018; Herrero & Xu, 2017), agreeing with the conclusions regarding China's ODI (Du & Zhang, 2018). Besides, the deal-level results in Columns (3)–(5) of Panel C are also quantitatively similar to our main findings. These results echo Gallagher and Irwin (2014) that loans from state-owned creditors to projects under the “going global strategy” enjoy subsidized interest rates. In comparison, all the coefficients in Panel D become statistically insignificant, suggesting that BRI borrowers in the noninfrastructure sectors are treated similarly regardless of the policy announcement.

We also conduct a variance inflation factor (VIF) test by using these variables to check multicollinearity. The mean of all variables is 2.39, indicating that the multicollinearity issue is not a concern for this study. Overall, our results show that loans from Chinese policy banks prefer borrowers in BRI countries, especially those along the continental route and in the infrastructure sectors after the policy announcement, which is in line with our first hypothesis.

6 HETEROGENEITY ANALYSIS

In Table 3, we uncover the heterogeneity in the main relationship between Chinese policy banks and the BRI borrowers after the BRI announcement. Panel A shows the triple DDD estimates for the channel variables, the economic performance. The aggregate-level results in Columns (1) and (2) suggest that more loans (in terms of deals and amounts) flow to BRI participants with lower prepolicy GDP. This result echoes extant literature on China's state-driven lending support to the developing world (Dreher & Fuchs, 2016; Dreher et al., 2018; Kaplan, 2016).

| Aggregate | Deal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: Economic performance | |||||

| Post × BRI country × Avg. GDP (log) | −0.240** | −3.301** | 1.216*** | −0.253** | 2.483* |

| (0.118) | (1.595) | (0.187) | (0.119) | (1.177) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Panel B: Institutional quality | |||||

| Post × BRI country × Avg. WGI | −0.290** | −4.750** | −2.579*** | −1.268*** | 3.954*** |

| (0.142) | (2.191) | (0.219) | (0.125) | (0.445) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Panel C: Political relations | |||||

| Post × BRI country × Avg. UN voting | 2.147*** | 27.260*** | −3.639*** | −5.674*** | 3.033*** |

| (0.447) | (7.780) | (0.417) | (0.0125) | (0.439) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel D: Economic performance | |||||

| Post × BRI country × Avg. GDP (log) | 0.212** | 2.309** | −0.597** | −0.226** | 0.145*** |

| (0.0858) | (1.143) | (0.289) | (0.101) | (0.0530) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Panel E: Institutional quality | |||||

| Post × BRI country × Avg. WGI | 0.300** | 4.458** | −0.766* | 0.202 | 0.408* |

| (0.146) | (2.027) | (0.395) | (0.145) | (0.203) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Panel F: Political relations | |||||

| Post × BRI country × Avg. UN voting | 0.248 | 3.810 | −1.497 | −0.367 | −0.236 |

| (0.210) | (3.060) | (1.045) | (0.219) | (0.226) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table examines the heterogeneous impacts of Chinese policy banks increasing their loan deals and amount towards BRI participant countries with preferential terms after the policy announcement. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results based on Equation (3) and Columns (3)–(5) are the deal level results. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are only added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; UN, United Nations; WGI, Worldwide Governance Indicators.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

However, at the deal level, the nonpricing terms of loans from policy banks share similar patterns with loans from nonpolicy commercial banks. As borrowers in countries with weaker economic performance have a higher risk of default, the associated collateral requirement is higher along with the shorter approved maturity. Following Hypothesis 2, Chinese state-owned policy banks provide loans to meet the development needs of BRI borrowers with weaker economic performance.

Next, we compare the lending responses of Chinese policy banks towards BRI borrowers with different institutional quality in Panel B of Table 3. The first two columns show that Chinese state-owned policy banks demonstrate a more supportive role at the aggregate level than nonpolicy banks. In contrast, both banks share similar lending patterns at the deal level in Columns (3)–(5) regarding loan spreads and maturity, though nonpolicy banks are less responsive than policy banks. These results infer that nonpolicy banks might be more prudent when lending to BRI countries with inferior institutional quality than policy banks, especially at the aggregate level. In other words, policy banks are more aggressive at both the aggregate and deal levels. Hence, in line with Hypothesis 3, our findings distinguish from prior literature that China's cross-border lending is independent of recipients' institutional quality (Buckley et al., 2007; Cheung & Qian, 2009; Dollar, 2018; Dreher & Fuchs, 2016).

In Panel C, we also examine whether the BRI borrowers with different prepolicy political relations with China alter the lending decisions of Chinese policy banks after the policy shock. Columns (1) and (2) suggest that BRI borrowers in countries with similar political interests to China receive more loan support from Chinese state-owned policy banks. This finding is in line with previous literature by Firth et al. (2008), who argue that state banks lend a helping hand to corporate borrowers due to political goals. It is possible because the credits could serve as a reward or inducement for recipients to vote in line with China (Dreher et al., 2018; Kraay, 2014; Mattlin & Nojonen, 2015). In contrast, nonpolicy banks (in Panel F) are not politically motivated, thus being less sensitive to borrower countries' political relations with China. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is also validated.

7 ROBUSTNESS CHECK

In this section, we present some additional tests to show the robustness of our main results.

7.1 Parallel trend test

Other variables and fixed effects are similarly defined in Equation (1). The deal-level model is similarly specified as Equation (2) by replacing the actual policy treatment date with the time dummies and interaction terms. The results in Table 4 show no statistical difference in trends between the two groups in the preshock periods, as all the interaction terms before 2014 are insignificant at both the country aggregated and the deal levels. Thus, the parallel trend assumptions are valid in this study.

| Aggregate | Deal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| 2011 × BRI country | 0.0670 | 0.185 | 0.0276 | −0.250 | 0.486 |

| (0.0653) | (1.222) | (0.157) | (0.169) | (0.582) | |

| 2012 × BRI country | −0.0946 | −2.657 | 0.604 | 0.250 | −0.790 |

| (0.0533) | (1.894) | (0.313) | (0.222) | (0.515) | |

| 2013 × BRI country | 0.0952 | −0.981 | 0.571 | 0.150 | −0.401 |

| (0.0979) | (1.807) | (0.482) | (0.222) | (0.641) | |

| 2014 × BRI country | 0.182*** | 2.868** | −1.033** | −0.450** | 0.897*** |

| (0.0485) | (1.046) | (0.258) | (0.200) | (0.0304) | |

| 2015 × BRI country | 0.140* | 2.296** | −0.501** | −0.450* | 1.245** |

| (0.0636) | (0.870) | (0.190) | (0.228) | (0.612) | |

| 2016 × BRI country | 0.0298 | 0.833 | 0.416 | 0.250 | 0.988 |

| (0.0985) | (2.227) | (0.445) | (0.169) | (0.732) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel B: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| 2011 × BRI country | −0.0687 | −3.321 | −0.0852 | −0.255 | −0.0774 |

| (0.147) | (2.576) | (0.301) | (0.217) | (0.156) | |

| 2012 × BRI country | 0.0130 | −1.174 | 0.140 | −0.200 | 0.00956 |

| (0.143) | (2.239) | (0.322) | (0.308) | (0.219) | |

| 2013 × BRI country | 0.242 | 1.645 | −0.341 | −0.311 | 0.0655 |

| (0.155) | (2.218) | (0.463) | (0.375) | (0.186) | |

| 2014 × BRI country | −0.181 | −1.919 | 0.0879 | −0.270 | −0.0959 |

| (0.182) | (2.627) | (0.387) | (0.192) | (0.226) | |

| 2015 × BRI country | 0.0920 | 1.129 | −0.0838 | −0.216 | −0.0740 |

| (0.180) | (2.249) | (0.444) | (0.138) | (0.188) | |

| 2016 × BRI country | −0.0388 | 1.166 | 0.207 | −0.194 | 0.0288 |

| (0.179) | (2.489) | (0.481) | (0.269) | (0.192) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table shows the parallel trend test on the impact of the BRI on the loans to firms from BRI countries. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results based on Equation (4), and Columns (3)–(5) are at the deal level. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

7.2 Placebo test

Second, we also perform a placebo test to demonstrate the robustness of our main findings further. We set 2011 as the falsified policy announcement year and only the remaining pretrend periods (i.e., 2010–2013) as our new sample size. We then re-estimate Equation (1) based on the new sample at the country aggregate level. For the deal-level analysis, we use September 7, 2011, as the supposititious BRI announcement date and exclude observations after the actual announcement date September 7, 2013. We retest our Equation (2) using this reduced sample. Table 5 finds statistically insignificant results of the falsified policy announcement dates at the country aggregate and deal levels.

| Aggregate | Deal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.130 | −3.736 | 0.682 | 0.416 | −0.086 |

| (0.238) | (4.917) | (0.598) | (0.825) | (0.290) | |

| Observations | 171 | 171 | 58 | 30 | 100 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel B: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.235 | −4.203 | 0.665 | −0.117 | −0.268 |

| (0.224) | (3.309) | (0.400) | (0.230) | (0.236) | |

| Observations | 162 | 162 | 251 | 349 | 534 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table indicates the placebo test on the impact of the BRI on the loans to firms from BRI countries. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results based on Equation (1), using 2011 as the falsified policy announcement year and only the remaining pretrend periods (i.e., 2010–2013) as the new sample size. Columns (3)–(5) are at the deal level and use September 7, 2011, as the supposititious BRI announcement date and exclude observations after the actual announcement date, September 7, 2013. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

7.3 Alternative sampling: Non-Chinese borrowers

One may also be concerned about two endogeneity issues resulting from the demand and supply side. The first one is the potential source of the omitted variable bias, which is likely to be correlated with both the BRI implementation and loan responses. For instance, prior literature claims that concessional loans from Chinese state-owned policy banks to developing countries often remain within the Chinese financial system through the bank account of Chinese lead contractors under the context of BRI (Horn et al., 2021; Mattlin & Nojonen, 2011). We restrict our sample by dropping the borrowers whose parent firms are from China to mitigate this concern. In other words, we exclude borrowers pertaining to Chinese subsidiaries in the BRI countries.

In Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, our results are entirely consistent with those in Table 2. These findings squarely suggest that the aggregate number and volumes of loans increase significantly even for foreign borrowers in the BRI countries rather than merely for Chinese borrowers after the policy initiative. Moreover, the deal-level results after excluding overseas Chinese firms, as shown in Columns (3)–(5), are in line with our baseline estimates of the full sample (i.e., Table 2). Therefore, we unveil a different lending pattern of state-linked lenders in the international syndicated loan market, which is commercial in nature.

| Aggregate | Deal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.250** | 5.487** | −1.469*** | −0.601** | 0.941*** |

| (0.101) | (2.150) | (0.121) | (0.260) | (0.255) | |

| Observations | 312 | 312 | 90 | 130 | 129 |

| Panel B: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.225** | 3.994** | −1.205*** | −0.932** | 1.028* |

| (0.082) | (1.706) | (0.186) | (0.291) | (0.551) | |

| Observations | 144 | 144 | 56 | 44 | 41 |

| Panel C: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.321** | 8.475*** | −0.890*** | −0.354*** | 0.770*** |

| (0.146) | (2.811) | (0.133) | (0.010) | (0.090) | |

| Observations | 168 | 168 | 47 | 39 | 40 |

| Panel D: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.121 | −0.452 | −0.190 | 0.0366 | 1.269* |

| (0.148) | (2.468) | (0.335) | (0.191) | (0.643) | |

| Observations | 216 | 216 | 43 | 91 | 89 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel E: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.216 | 2.292 | −0.346 | 0.161* | −0.104* |

| (0.133) | (2.038) | (0.246) | (0.095) | (0.054) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 737 | 1080 | 963 |

| Panel F: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.242 | 2.128 | 1.089* | −0.0886 | −0.276** |

| (0.264) | (3.233) | (0.617) | (0.257) | (0.126) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 189 | 333 | 288 |

| Panel G: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.0628 | 0.811 | 0.714 | 0.171 | 0.247 |

| (0.140) | (1.965) | (0.414) | (0.168) | (0.180) | |

| Observations | 294 | 294 | 219 | 333 | 331 |

| Panel H: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.112 | 3.073 | −0.290 | 0.181* | −0.115 |

| (0.121) | (1.840) | (0.255) | (0.102) | (0.072) | |

| Observations | 366 | 366 | 518 | 747 | 632 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table assesses the impact of the BRI on loans towards borrowers using non-Chinese borrowers as a subsample. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results and Columns (3)–(5) are at the deal level. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

7.4 Alternative sample: Non-Chinese lenders

Another possible concern is the sample selection of Chinese lenders. Chinese banks with greater loan balances are usually state-owned. The BRI participant countries may aim at state-to-state trade cooperation such as export quotas and input product discounts rather than banks' loans. One might wonder if the effect of BRI implementation came from other omitted factors correlated with the policy initiative and the lending responses. To formally address this issue, we use an alternative sample of all non-Chinese lenders to re-estimate Equations (1) and (2) and confirm our main findings.

Unsurprisingly, the statistical significance of all the coefficient estimates in Table 7 vanishes. In other words, we could hardly find any difference for non-Chinese lenders between lending patterns to BRI and non-BRI borrowers, even along the continental route and the maritime route, and the infrastructure sectors. Thus, this finding also substantiates our claim that Chinese policy banks render more financial support to BRI participants after the BRI announcement.

| Aggregate | Deal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) |

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.06 | −0.575 | 0.068 | 0.023 | −0.011 |

| (0.083) | (0.884) | (0.102) | (0.023) | (0.030) | |

| Observations | 768 | 768 | 149,197 | 183,272 | 190,450 |

| Panel B: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.043 | 0.874 | 0.176 | 0.012 | 0.050 |

| (0.143) | (1.112) | (0.158) | (0.028) | (0.051) | |

| Observations | 300 | 300 | 21,355 | 44,926 | 34,822 |

| Panel C: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.111 | 0.816 | 0.095 | −0.014 | 0.017 |

| (0.107) | (1.26) | (0.189) | (0.030) | (0.049) | |

| Observations | 588 | 588 | 32,068 | 45,566 | 46,213 |

| Panel D: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.041 | 0.302 | 0.060 | 0.024 | −0.017 |

| (0.084) | (0.995) | (0.106) | (0.028) | (0.039) | |

| Observations | 618 | 618 | 117,129 | 137,706 | 144,237 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the impact of the BRI on loans towards borrowers using non-Chinese lenders as an alternative sample. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results and Columns (3)–(5) are at the deal level. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

7.5 Alternative proxy for policy treatment: Year of signing the BRI agreement

The results are reported in Table 8. Columns (1)–(2) find positive and significant coefficients for the aggregate-level results, implying that the lending decisions targeting BRI countries are roughly the same. On the deal level, the coefficients in Columns (3)–(5) present strikingly consistent findings that loans from Chinese policy banks to those borrowers are correlated with a lower spread than those of nonpolicy banks.

| Variables | Aggregate | Deal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) | |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.243* | 5.909** | −17.51*** | −0.284** | 1.240** |

| (0.142) | (2.846) | (2.314) | (0.122) | (0.528) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Panel B: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.295** | 5.332* | −1.379* | −0.278* | 0.277*** |

| (0.132) | (3.001) | (0.543) | (0.149) | (0.091) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Panel C: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.288** | 5.523* | −0.173*** | −0.577*** | −0.033 |

| (0.137) | (2.930) | (0.001) | (0.166) | (0.245) | |

| Observations | 174 | 174 | 75 | 56 | 40 |

| Panel D: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.053 | 2.022 | 0.321 | 0.173 | −1.800*** |

| (0.144) | (2.575) | (0.383) | (0.243) | (0.539) | |

| Observations | 228 | 228 | 139 | 95 | 129 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel E: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.062 | 2.059 | 0.106 | −0.012 | −0.291 |

| (0.172) | (2.172) | (0.485) | (0.201) | (0.355) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Panel F: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.145 | 3.333 | 0.398 | −0.114 | 0.033 |

| (0.131) | (3.001) | (0.265) | (0.094) | (0.121) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Panel G: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Treatpost | −0.257 | −0.492 | −0.879 | −0.291 | 0.164 |

| (0.200) | (3.084) | (0.831) | (0.181) | (0.115) | |

| Observations | 294 | 294 | 221 | 335 | 333 |

| Panel H: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Treatpost | 0.211 | 2.438 | 0.102 | −0.146 | −0.277 |

| (0.157) | (2.315) | (0.585) | (0.131) | (0.358) | |

| Observations | 366 | 366 | 1722 | 857 | 2731 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the impact of the BRI on loans toward borrowers based on the signing time of the BRI agreement as an alternative policy treatment. Columns (1) and (2) are the country aggregated results based on Equation (5) and Columns (3)–(5) are at the deal level. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

7.6 Additional control variable: Creditworthiness

Our baseline model may still be subject to the omitted variable bias. For instance, in addition to economic growth, a country's creditworthiness could also affect its oversea borrowing (Tiruneh, 2004). Thus, our DID estimates in Table 2 could be biased since countries' credit situation is omitted. To address this issue, we follow Khayat (2020) and use domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP) to proxy the borrower country's creditworthiness. We do not use total credit to GDP since it would double count the oversea lending. The domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP) data is from the World Development Indicators (WDI). We re-estimate all the regressions in Table 2 by controlling countries' creditworthiness and we report the results in Table 9. Not to our surprise, the estimates are statistically and economically similar (though slightly smaller in magnitude) to our baseline results, indicating that the omitted credit variable does not affect our main conclusions.

| Variables | Aggregate | Deal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| No. of deals (log) | Aggregate amount (log) | Spread | Whether secured | Maturity (log) | |

| Policy banks | |||||

| Panel A: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.266*** | 5.132*** | −0.539** | −0.503** | 0.603** |

| (0.097) | (1.786) | (0.206) | (0.210) | (0.238) | |

| Observations | 378 | 378 | 197 | 151 | 169 |

| Panel B: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.226** | 4.128** | −0.740** | −0.881** | 2.936*** |

| (0.095) | (1.668) | (0.303) | (0.355) | (0.452) | |

| Observations | 150 | 150 | 58 | 51 | 41 |

| Panel C: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.325** | 8.903*** | −0.886*** | −0.352*** | 0.759*** |

| (0.145) | (2.770) | (0.131) | (0.009) | (0.086) | |

| Observations | 174 | 174 | 75 | 56 | 40 |

| Panel D: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.159 | −1.616 | −0.308 | 0.009 | 1.148 |

| (0.160) | (2.151) | (0.304) | (0.185) | (0.689) | |

| Observations | 228 | 228 | 139 | 95 | 129 |

| Nonpolicy banks | |||||

| Panel E: BRI versus non-BRI | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.195 | 1.853 | −0.252 | 0.142* | −0.150*** |

| (0.130) | (1.978) | (0.222) | (0.080) | (0.043) | |

| Observations | 546 | 546 | 1943 | 1192 | 3064 |

| Panel F: Continental route versus maritime route | |||||

| Post × Continental route | 0.243 | 2.177 | 0.875 | −0.075 | −0.281** |

| (0.251) | (3.235) | (0.681) | (0.243) | (0.119) | |

| Observations | 204 | 204 | 198 | 351 | 299 |

| Panel G: Infrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | −0.073 | 0.751 | 0.868** | 0.168 | 0.233 |

| (0.142) | (1.951) | (0.401) | (0.169) | (0.179) | |

| Observations | 294 | 294 | 221 | 335 | 333 |

| Panel H: Noninfrastructure sectors | |||||

| Post × BRI country | 0.185 | 2.852 | −0.132 | 0.154* | −0.198*** |

| (0.140) | (1.910) | (0.246) | (0.081) | (0.063) | |

| Observations | 366 | 366 | 1722 | 857 | 2731 |

| Loan characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table shows the impact of BRI on Chinese policy banks' overseas lending responses to firms from BRI countries. Creditworthiness is measured by the ratio of a country's domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP) and is considered in all specifications. Country and year fixed effects (FE) are controlled in all columns, while industry FE and loan characteristics are added in Columns (3)–(5). Robust standard errors are clustered by borrower country level and reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

8 CONCLUSION

This paper investigates Chinese policy banks' lending responses to firms from BRI countries relative to Chinese nonpolicy banks, using loan-level data from 2010 to 2016. Our empirical results show that Chinese policy banks increased lending to BRI countries' firms in the number of loans and the aggregate loan amount relative to the non-BRI countries after the initiative. At the deal level, we also confirm that loans from Chinese policy banks to BRI borrowers after the policy initiative are associated with reduced spread, lowered collateral requirement, and extended maturity. Such effect was more pronounced among firms residing along the continental route and in the infrastructure sectors.

Moreover, our findings illustrate that Chinese policy banks gave more support to firms from BRI countries with weaker economic performance, more fragile institutional quality, and closer political interests. The qualities of Chinese state-owned policy banks demonstrate a patient capital characteristic (Kaplan, 2016), which focuses on the development potential of borrower countries rather than the immediate economic return under market-based criteria. This lending strategy relies on the home government's implicit guarantee for loan security. It aims for more substantial benefits from long-term relations with participant countries in the form of commercial opportunities.

Our study provides evidence that Chinese policy banks actively respond to the policy initiative in the international syndicated loan market. The aggregate and disaggregate lending results may help policymakers and multinational corporations understand the involved financial parties and the recipients' profiles. Our research pinpoints the primary driver of financial resources and thus informs future BRI participants. Overall, this study contributes to the literature by showing the supportive role played by Chinese policy banks in international syndicated loans under the BRI.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Xin Chen: Investigation; project administration; writing–original draft. Heyang Fang: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis. Yun Liu: Project administration; validation; writing–review & editing. Yifei Zhang: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None declared.

APPENDIX A:

| Variables | Definitions | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Aggregate level | ||

| No. of deals (log) | Natural logarithm of the country-year-aggregated number of syndicated loan deals. | Dealscan |

| Aggregate amount (log) | Natural logarithm of the country-year-aggregated number of syndicated loan amounts. | Dealscan |

| Avg. GDP (log) | Natural logarithm of the 4-year average GDP before the BRI (i.e., 2010–2013). | Penn World Table 9.0 |

| Avg. WGI | The 4-year average of the WGI indicator before the BRI (i.e., 2010–2013). The WGI indicator is constructed by averaging the six governance dimensions. | World Bank |

| Avg. UN voting | The 4-year average of the ideal points distance before the BRI (i.e., 2010–2013). The ideal points distance, constructed from countries' votes, represents the similarity between each country's foreign policy and China's. | Bailey et al. (2017) |

| Creditworthiness | The ratio of a country's domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP). | World Bank |

| Panel B: Deal level | ||

| Spread | Loan spread over LIBOR, in basis points. | Dealscan |

| Whether secured | A dummy variable equals one if the loan is secured and zero otherwise. | Dealscan |

| Maturity (log) | Natural logarithm of the loan maturity. | Dealscan |

- Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; UN, United Nations; WGI, Worldwide Governance Indicators.

| Total country | BRI country | Continental route | Belarus, Belgium, Hungary, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Netherlands, Oman, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan; |

| Maritime route | Bangladesh, Burundi, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Indonesia, Kenya, Kiribati, South Korea, Nigeria, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam; | ||

| Other countries | Angola, Argentina, Australia, Bahamas, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, Ghana, India, Luxembourg, Mauritius, Monaco, Mozambique, Norway, Panama, Philippines, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, USA, Venezuela. |

- Note: This table lists the detailed country list of our full sample. We classify the total country into BRI and non-BRI countries. We further divide the BRI country into two subgroups based on the route type: continental or maritime route, disclosed by the central government.

REFERENCES

- 1 In this study, we refer to a firm-level syndicated loan as one deal.

- 2 The Chinese state-owned policy banks include the Agricultural Development Bank of China, China Development Bank, and China Export-Import Bank.

- 3 State banks, including the state-owned commercial banks and the policy banks, are still the dominant players in the financial system in China (Shih, 2004).

- 4 See Appendix Table 2 for the detailed country list regarding BRI and non-BRI countries and their route type.

- 5 Horn et al. (2021) point out that cross-border loans issued by Chinese official lenders to risky borrowers are mostly directed to Chinese firms that operate projects in the recipient countries.

- 6 We identify a company in foreign countries as a Chinese borrower based on four criteria: (1) Chinese enterprises; (2) the company has a Chinese controlling shareholder with shareholding larger or equal to 30%; (3) the actual controller is the state; (4) private companies who operate entirely in Mainland China.

- 7 The infrastructure sectors in our sample mainly incorporate mining, transportation, and energy, and we manually identify the borrowers in the infrastructure sectors based on the industry SIC code provided by Dealscan.

- 8 See Appendix Table 1 for detailed variable definitions.

- 9 The scale of our UN voting similarity score is similar to that of Bailey et al. (2017) which ranges from −3 to 3 for the five permanent members of the UN Security Council in the United Nations General Assembly.