Way of love and after-marriage well-being: Evidence from China

Abstract

Based on 2010 China Family Panel Studies, we use Ordered Probit, Instrumental Variables, and Conditional Mixed Process to analyze the effect of different ways of love on after-marriage well-being. The findings are: (i) Compared with arranged marriage, free love can significantly increase the well-being of married residents. (ii) In heterogeneity analysis, the promotion effect of free love on well-being is more obvious among the couples 2 years after marriage, residents with positive personal values, the post-80s, and rural areas. (iii) In mechanism analysis, married residents who met through free love will significantly enhance their ability to get along with others, increase their intimacy with their spouses, improve family harmony, and reduce their emphasis on family succession, thus further enhancing their well-being.

1 INTRODUCTION

“Marriage is more than being together” (Kefalas et al., 2011). Nowadays, young adults not only marry and have children later than previous generations, but they also take more time to get to know each other before tying the knot. Marriage means a lot for young adults: even if they get married, the well-being of both husband and wife could also be affected by various problems (Carr et al., 2014). Nearly half of all married people regret “walking down the aisle”: the issue is so common that it's even got the name “Post-nuptial remorse.” Especially in China, nearly 63.3% of married couples had ever regretted getting married.1 This discordant family element may affect after-marriage well-being, generate intergenerational transmission, and harm social harmony and stability. The reason behind this, besides the irreconcilable contradiction between the husband and wife, may be caused by different approaches in initial acquaintance. As to subjective well-being, the free love marriage is also significantly higher than the arranged marriage.2

Based on the Chinese Marriage Well-being Index in 2018, for those who had ever regretted getting married, the percentage of arranged marriage is significantly higher than free love (the TGI of arranged marriage is 45.2 higher than free love).3 Besides, the probability of mental or physical derailment of the arranged marriage couple was significantly higher than the free love marriage couple (7.8% higher). Thus, compared with free love, the after-marriage well-being of arranged marriage partners is lower.

As for the ways of marriage acquaintance, there were only a few ways in ancient times, such as parents' orders and matchmakers' words. With the development of the economy, there are more ways to know each other, such as online chat, marriage introduction, and various forms. Whether these diversified forms of marriage can be freely chosen by residents will greatly affect the well-being and stability of life after marriage. Therefore, the way of love could be divided into meeting at school, meeting at the workplace, meeting at the residence, introduced by friends, arranged by parents and so on4.

In different countries and cultures, researchers have studied the relationship between way of love and after-marriage well-being with opposite results. Some say arranged marriages are happier and last longer than free love marriages (Epstein et al., 2013; Gupta & Singh, 1982). For example, Gupta and Singh (1982) visited 50 couples in the northwestern Indian city Jaipur and found that couples who married in love began to show less affection for each other after 5 years of marriage. In contrast, couples who were married by their parents' arrangement started out with a low love level, but their feelings gradually increased and after 5 years, they greatly surpassed those who were married by free love.

On the contrary, some scholars believe that free love marriage is happier. With the popularization of social freedom and equality, free love marriage is becoming more and more popular. In the mainstream economic theory, people's preferences are diversified: the more opportunities there are, the higher utility they have (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2010). Compared with arranged marriage, free love marriage allows young couples to freely use all kinds of capital, such as bride price and dowry, more conducive to personal after-marriage well-being and family harmony (Edlund & Lagerlöf, 2006).

In all, there are differences in the subjective well-being evaluation of individuals in different types of marriage, which may be related to regions, cultures, and personal concepts. Marriage is often seen as a starting point of a happy life (White et al., 1986), and the way of love should also have profound influence on the after-marriage well-being. We attempt to explore the effect of way of love on after-marriage well-being, a supplement to the existing literature on marriage and well-being.

To this end, we use the survey data of China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in 2010. First, we found that compared with arranged marriage, free love marriage significantly improves the after-marriage well-being of married residents. To alleviate the potential missing variables to some extent, we attempt to select “the sex ratio of unmarried groups in 1996 and the urbanization rate in 1964” as the instrumental variables of free love, and the conclusion is still valid. Second, marriageable age, individual personality or age, family structure, and region have different influences on couples' after-marriage well-being (Asadullah et al., 2018). We found that the promotion effect of way of love on after-marriage well-being is more obviously within 2 years after marriage, in residents with positive values, the post-80s, and in rural areas. Third, we try to select the close relationship with the spouse, family harmony, and fertility as the proxy indicator of interpersonal relationships to conduct the mechanism test. We found that the interpersonal relationship will significantly increase residents' ability to get along with people, increase their intimacy with their spouses, and reduce the emphasis on money and procreation.

The possible contributions are as follows: First, from the perspective of the way of love exploring after-marriage well-being could enrich the existing literature on marriage and well-being. Second, from the aspects of getting along with others, attaching importance to money, intimate relationship with spouse, and fertility, we probe into the influence of the way of love on the living state of the residents after marriage. It is helpful to further guide the youth-adult to establish a correct view of love and marriage, and further promote family harmony and social stability.

The rest of this paper is as follows: Section 2 describes the literature review and hypothesis. Section 3 provides the model, data, and descriptive statistics. Section 4 reveals empirical results analysis. Section 5 presents the conclusion.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS

2.1 Literature review

Well-being is a subjective feeling, so it has always been considered in the field of psychological research. In fact, classical and neoclassical economics is precisely based on people's subjective feelings, and utility is used to measure people's well-being and satisfaction. Married life is often regarded as an important part of people's well-being, which has been repeatedly confirmed by many researchers (White et al., 1986). Diener et al. (2004) found that marriage can provide people with economic security, increase people's economic sources, and thus improve people's well-being. Luo and Klohnen (2005) concluded that there is a strong correlation between the homogeneity of some factors among spouses and subjective well-being. For the theoretical basis of marriage and satisfaction, we mainly discuss the sociology of choice theory and economics of marriage matching theory.

According to the choice theory in the field of sociology, the single choice may be a bad thing, and diversity of choice may improve satisfaction (Iyengar & Warburton, 2011). According to this theory, arranged marriages mean that the range of marriage partners is designated by parents or a third party, so the choices are limited. However, free love marriage means that the choice of a marriage partner is not subject to others, and all people that they know or may know are possible marriage partners. This theory is also consistent with the Chinese Marriage and Love Report, which shows that most of the emotional disputes or conceptual contradictions after marriage are caused by the single choice of initial acquaintance mode. In terms of the happiness index, free love is also significantly higher than arranged marriage.5

Choice theory provides an explanation for the practical significance of “free love tide,” but an important reason why most young people resist parents' arranged marriage is whether there is love in parents' arranged marriage. Xiaohe and Whyte (1990) think that the traditional marriage is arranged by parents, and most young people at marriageable age will be arranged by parents, but both husband and wife may have no emotional foundation. With the development of society, arranged marriage has changed to free love obviously. Some scholars also think that marriage in free love is happier. Huang et al. (2012) investigated the marriage satisfaction between arranged marriage and free love in China, the results show that free love is happier than arranged marriage.

Most of the studies are discussed from the sociological point of view, while few studies are theoretically or empirically analyzed from the economic point of view, especially those that directly pay attention to the influence of the cognitive approach with spouse on the well-being after marriage. Most of the literature studies the relationship between the marriage matching model and marriage quality from the theory of marriage-matching. The research of Rogler and Procidano (1989) found that age mismatch and the social class difference had no correlation with the potential risk of divorce. Watson et al. (2004) found that marital satisfaction was mainly related to their own personality characteristics by using the samples of newly married couples. At the same time, there was a significant positive correlation with the spouse's ability, vocabulary, and reasoning test, but there was no significant correlation with other similar factors, such as age and education level. The research of Luo and Klohnen (2005) showed that homogeneity of some factors between partners, such as political stand, is strongly correlated with subjective well-being.

With the rise of the divorce rate and the improvement of mate selection standards, it is particularly important to study the relationship between way of love and after-marriage well-being. Although many scholars have done a lot of work on the marriage, there is not much on marital well-being from the perspective of acquaintance. Free love and parents' arrangement are not only life choices but also two ways of marriage-matching. Edlund and Lagerlöf (2006) believed that, compared with marriages in which parents participate, free love allows young couples to master the right to use betrothal gifts and thus is more conducive to marital happiness. Huang et al. (2012) used Chinese data to conduct empirical research, and the results showed that free love was happier. Furthermore, Huang et al. (2017) established a theoretical model of marriage matching, which divided the matching methods into free love and parental participation. They found that couples whose parents participated in marriage matching took care of their parents more after marriage, but this filial piety was at the expense of the happiness of the couple, which was consistent with Becker et al. (2016). Different from the existing literature, this paper aims to further improve the previous studies, introduce the cognitive approach to arranged marriage, and study the influence of free love and arranged marriage on happiness, which also enriches the research of marriage matching and happiness.

2.2 Hypothesis

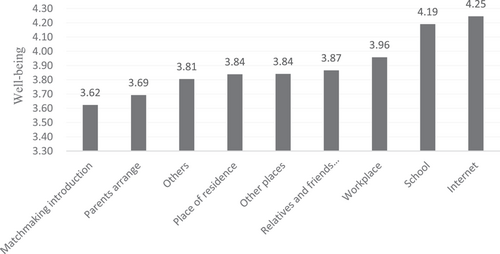

Mainstream economics believes that people's preferences have diversity, and the more choices, the more utility. The difference between free love and parental arrangement lies in the choice of marriage partners: free love has a wider range of partners, while the parental arrangement is chosen by parents and has a smaller range of options. To understand the heterogeneity of the influence of different cognitive approaches on residents' subjective well-being on different occasions, Figure 1 depicts the well-being score of different ways of love (acquainted at different locations) among the investigated groups. We found that met through Internet has the highest score (4.25) followed by through school (4.19) and workplace (3.96). Parents' arrangement and matchmaking are significantly lower than other types. We need to further explore the ways that way of love affects after-marriage well-being from the perspective of personal concepts and family values. The people who choose arranged marriage with their parents may be likely to have difficulties in free love in their real life. The way of love may also affect the subjective after-marriage well-being through the change of personal thoughts and family concepts. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

-

Hypothesis 1: Compared with arranged marriage, free love significantly improves the well-being of married residents.

In general, women's after-marriage well-being is higher than that of men, possibly because women have less responsibility and work stress than men (Perelli-Harris et al., 2019). The increase in personal income does have a significant increase in after-marriage well-being (Lucas, 2007). However, well-being reflects people's living conditions: it is inevitable for them to compare their actual income with average social income and personal expected income. Hence, the relationship between relative income and well-being should be more emphasized (Caporale et al., 2009). As married life tends to be gradually ordinary, after-marriage well-being may be highly affected by marriageable age (Johnson et al., 2017). Personal values and ethics also have a significant impact on after-marriage well-being: For instance, those who overemphasize material wealth may have a lower level of after-marriage well-being (Biswas-Diener, 2008). Compared with the post-1960s and post-1970s generation, the post-1980s generation may be more open in mind under the wave of reform and opening-up, and free love may have a greater impact on this group (Wang, 2013). A larger proportion of married couples with children have experienced arranged marriages, and they may bear more reproductive pressure from parents or other family members. Therefore, families with children are less happy in arranged marriages between parents (Huang et al., 2012). Due to the lack of adequate economic and social security in rural areas, there is a huge difference between the happiness of free love and marriage arranged by parents. When parents or a third party help to find a blind date, they are more inclined to choose the one with strong economic strength, that is, they tend to use money to replace love (Huang et al., 2017). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Way of love affect after-marriage well-being by sex, relative income, marriageable age, personal values, age, family structure and region.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Model specification

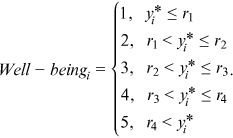

are different cut-off point. When the disturbance term distribution conforms to the normal distribution, it is the Ordered Probit model. The key to selection lies in latent variables yi*, the equation of latent variables is shown in Formula (1). Based on Clark et al. (2010), we established the following econometric model:

are different cut-off point. When the disturbance term distribution conforms to the normal distribution, it is the Ordered Probit model. The key to selection lies in latent variables yi*, the equation of latent variables is shown in Formula (1). Based on Clark et al. (2010), we established the following econometric model:

()

()Well-beingi is the after-marriage well-being of respondent i, Free Lovei is the way of love. Xi is a set of control variables, including individual level, family level, and local level factors. εi is the random disturbance term. Most importantly, the exact residence status could not be obtained before this survey, a probability sampling weight was assigned to each person in the CFPS, which corresponds to the representation of the residents in the population. Hence we use such sample weights in all our analyses.

3.2 Endogeneity discussion

In general, how you meet your current spouse affects the after-marriage well-being of the current married group, but could it be the other way around? We believe that we can only get married after meeting our present spouse, and there will be no problem that the level of after-marriage well-being will in turn affect the couple's cognitive approach, and the reverse cause is relatively weak. In addition, while the previous models control as many personal, family, and provincial variables as possible, it is still possible that other factors such as cultural atmosphere and regional environment, affect the way of love and well-being simultaneously. In a word, no matter what kind of situation is mentioned above, it means that free love is a kind of self-choice behavior, not a random occurrence. This will lead us to be unable to correctly infer the effect of free love on the well-being of married residents.

Then, we consider using the Generalized Ordered Probit Model without parallel regression assumption to test the robustness, and the results of the variable we are interested in-Free Love-remain basically unchanged in all results (Wooldridge, 2010). Meanwhile, the Ordered Probit Model imposes some quite strong identifying restrictions on the single crossing property for the marginal effects, we move stepwise from the lowest category y = 1 to the highest category y = 5, and the basic result of the marginal effects' estimation are first negative and then positive (β1 > 0), which is consistent with the single-crossing property for the marginal effects (Boes & Winkelmann, 2006). Therefore, we still use the Ordered Probit Model to estimate in the following estimation.

3.3 Selection of instrumental variables

To alleviate the potential bias of missing variables as much as possible, we employ the historical instrumental variables in the Ordered Probit Model. Historical variables are less likely to be related to the explained variables through macro factors, therefore, historical variables are relatively exogenous instrumental variables (Chen et al., 2020).

Specifically, we use two historical variables at the provincial level as instrumental variables: the sex ratio of unmarried groups in 19966 and the urbanization rate in 1964.7 The first instrumental variable is the sex ratio of unmarried people in 1996, that is, the ratio of the male population to the female population. If the unmarried male population is larger than the unmarried female population in one area, which means that the gender ratio in the area is unbalanced, and it is even more difficult for unmarried men to find suitable partners. Meanwhile, parents are more likely to interfere with their children's choice of marriage. The faster the sex ratio rises, the larger the value of the gender ratio. We conclude that the instrumental variable is negatively correlated with free love.

Another instrumental variable is the urbanization rate in 1964. Unmarried groups in areas with a high urbanization rate have a more open mind, and they are more likely to choose the way of free love. Therefore, we conclude that the urbanization rate in 1964 has a positive correlation with free love. Next, we need to consider the exogenous of urbanization rate in 1964 as an instrumental variable. The urbanization rate may affect the explained variables in other ways than free love. For example, residents in areas with a high urbanization rate have relatively good economic conditions, which leads to higher well-being, so they are not completely exogenous. Based on this, we add the control variables such as individual income and family income into the model. These variables can largely alleviate the endogeneity of the urbanization rate as an instrumental variable.

3.4 Data

We use the data from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) conducted by the China Social Science Survey Center of Peking University, and select the year 2010 for the empirical test. First, CFPS contains information related to the way individuals meet their spouses, including parents arrangement, at school, at the workplace, at residence, friend introduction, matchmaking, and through the Internet, which can better identify the influencing factors of after-marriage well-being and thus is consistent with the results of this paper. Second, the survey samples cover 25 provinces in China, with a target sample size of 16,000 households. The questionnaire consists of four main types: community, family, adult, and children. It is the most comprehensive and representative follow-up survey of Chinese families nationwide. Third, the data of 2010 is selected because it is the first year of the data survey, more representative than the surveys in the following rounds. Due to the absence of samples in subsequent rounds over time, the missing values of explanatory variables are also very serious.8

In this paper, the research object is limited to the married group over 20 years old (including 20 years old). According to the actual age calculated by the survey year, the legal marriageable age of Chinese males is above 22 years old, and that of Chinese females is above 20 years old. After eliminating the family records without personal codes and missing or inapplicable samples, the final sample size was 15,970, among which 7769 were males and 8201 were females. The definitions of each variable are shown in Table A2.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULT

4.1 Main model

Table 1 shows the estimation results of the Ordered Probit Model. The direction of the marginal effect of the independent variable on the minimum (maximum) of the dependent variable is opposite (same) to the sign of the coefficient, while for the value of the dependent variable in the middle, the sign of the coefficient is not always consistent with the direction of the marginal effect under the value of a particular independent variable. The marginal effect estimation gives more valuable information on the basis of verifying the global parameter estimation. Therefore, in columns (2)–(6) of Table 1, we also show the marginal impact of each option of well-being.

| Variables | Well-being | The marginal effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very unhappy | Unhappy | General | Happy | Very happy | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Free Love | 0.1284*** | −0.0068*** | −0.0106*** | −0.0274*** | 0.0011** | 0.0438*** |

| (0.0456) | (0.0024) | (0.0038) | (0.0098) | (0.0005) | (0.0155) | |

| Gender | −0.0752*** | 0.0040*** | 0.0062*** | 0.0161*** | −0.0006** | −0.0256*** |

| (0.0213) | (0.0011) | (0.0018) | (0.0045) | (0.0003) | (0.0072) | |

| Age | −0.0379*** | 0.0020*** | 0.0031*** | 0.0081*** | −0.0003*** | −0.0129*** |

| (0.0049) | (0.0003) | (0.0004) | (0.0010) | (0.0001) | (0.0017) | |

| Age2 | 0.0365*** | −0.0019*** | −0.0030*** | −0.0078*** | 0.0003*** | 0.0125*** |

| (0.0050) | (0.0003) | (0.0004) | (0.0011) | (0.0001) | (0.0017) | |

| Hukou | −0.1855*** | 0.0098*** | 0.0154*** | 0.0397*** | −0.0016*** | −0.0632*** |

| (0.0266) | (0.0014) | (0.0023) | (0.0057) | (0.0006) | (0.0091) | |

| Nationality | −0.0995** | 0.0053** | 0.0082** | 0.0213** | −0.0008* | −0.0339** |

| (0.0388) | (0.0021) | (0.0032) | (0.0083) | (0.0004) | (0.0132) | |

| Education | 0.0041 | −0.0002 | −0.0003 | −0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 |

| (0.0441) | (0.0023) | (0.0037) | (0.0094) | (0.0004) | (0.0150) | |

| Health | 0.2699*** | −0.0143*** | −0.0223*** | −0.0577*** | 0.0023*** | 0.0920*** |

| (0.0236) | (0.0014) | (0.0020) | (0.0050) | (0.0008) | (0.0080) | |

| Income | 0.0074*** | −0.0004*** | −0.0006*** | −0.0016*** | 0.0001** | 0.0025*** |

| (0.0028) | (0.0001) | (0.0002) | (0.0006) | (0.0000) | (0.0009) | |

| Work | 0.0124 | −0.0007 | −0.0010 | −0.0027 | 0.0001 | 0.0042 |

| (0.0229) | (0.0012) | (0.0019) | (0.0049) | (0.0002) | (0.0078) | |

| Internet User | 0.0916*** | −0.0048*** | −0.0076*** | −0.0196*** | 0.0008* | 0.0312*** |

| (0.0348) | (0.0019) | (0.0029) | (0.0074) | (0.0004) | (0.0119) | |

| Family Size | 0.0222*** | −0.0012*** | −0.0018*** | −0.0047*** | 0.0002** | 0.0076*** |

| (0.0059) | (0.0003) | (0.0005) | (0.0013) | (0.0001) | (0.0020) | |

| Province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 16,165 | 16,165 | 16,165 | 16,165 | 16,165 | 16,165 |

- Note: Robust standard error in brackets. Province is a province dummy variable.

- ***, **, and * are significant at the level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

The basic results showed that free love significantly improves the well-being of married residents. Specifically, free love can increase the probability of “happy” and “very happy” by 0.1% and 4.4% respectively. Hence, free love couples tend to have more positive emotional feelings, further enhancing residents' well-being.

4.2 Endogeneity discussion

Since the data used in this paper are observational data obtained through a sampling survey, for a normative empirical paper, endogeneity discussion, such as reverse causality, omission of variables, sample selection bias, and so forth, cannot be ignored. There is a need to discuss whether the observed married population is aware of possible endogeneity problems through different ways of love. For this problem, we try to select the instrumental variable to alleviate the endogeneity problem.

Specifically, we take two approaches. First, we use the conditional mixed process (CMP) estimation method9 to simultaneously estimate free love and after-marriage well-being determining equation. The set equation of well-being is the same, but the set equation of free love adds instrumental variables: The sex ratio of unmarried people in 1996 and the urbanization rate in 1964. This is mainly because the sex ratio of unmarried people and the urbanization rate have an important impact on individuals' free love choices. The results are presented in columns (1) of Table 2. It can be found that the positive effect of free love on subjective after-marriage well-being is still robust after using the CMP method.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | Free Love | 2SLS | Free Love | 2SLS | |

| Free Love | 0.1121** | 17.6585*** | 17.1972*** | ||

| (0.0424) | (4.0391) | (4.6631) | |||

| Sex ratio | −0.0024*** | ||||

| (0.0005) | |||||

| Urban64 | 0.0003*** | ||||

| (0.0001) | |||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| F value | 20.8781 | 17.4918 | |||

| Observations | 16,165 | 15,933 | 15,933 | 15,756 | 15,756 |

- Note: Columns (2) and (4) are the first-stage regression result of the instrumental variable, and columns (3) and (5) are the second-stage regression result of the instrumental variable. Robust standard error in brackets. Province is a province dummy variable.

- ***, **, and * are significant at the level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Second, we use the two-stage least squares estimation (2SLS), and the instrumental variable is the sex ratio of unmarried people in 1996 and the urbanization rate in 1964. For the relevance of the instrumental variable, it is closely related to the individual decision of free love (the first-stage F value is 20.88 and 17.49, which are greater than 10). The results shown in columns (3) and (5) of Table 2 further verify the conclusion.

4.3 Sub-sample regression

According to existing literature, marriageable age and personal characteristics have divergent effects on residents' well-being (Luhmann et al., 2012). Therefore, we attempt to explore the heterogeneous effect of way of love on subjective well-being from the perspectives of marriageable age and personal personality. The results are presented in Table 3.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Love | 0.6981** | −0.2472 | 0.3712** |

| (0.3149) | (0.1751) | (0.1480) | |

| Free Love × MarryAge3–7 | −0.9765** | ||

| (0.4375) | |||

| Free Love × MarryAge > 7 | −0.5672* | ||

| (0.3167) | |||

| Free Love × Confidence | 0.1060** | ||

| (0.0506) | |||

| Free Love × Money | −0.2719* | ||

| (0.1541) | |||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 16,165 | 16,138 | 16,165 |

- Note: MarryAge1–2, MarryAge3–7, MarryAge> 7 mean 1–2 years, 3–7 years, and over 7 years after marriage, respectively. We choose MarryAge1–2 as the base group, hence it does not show in the table. Confidence indicates the degree of confidence in the future (1 = “lowest” to 4 = “highest”); Money indicates how much you value money (1 = “lowest” to 4 = “highest”). Robust standard error in brackets. Province is a province dummy variable.

- ***, **, and * are significant at the level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Subjective well-being is based on value judgment. To what extent, the improvement of after-marriage well-being may be related to marriageable age or personal characteristics. Hence we set the intersection of free love with different marriageable ages (MarryAge1–2, MarryAge3–7, MarryAge > 7), personal confidence in the future (Confidence), and value of money (Money), and the results are shown in Table 3. In terms of marriageable age, we consider MarryAge1–2 as the base group, the intersection of Free Love × MarryAge3-7 and Free Love × MarryAge > 7 are significantly negative, which means marriageable age below 2 years has the largest promotion effect on after-marriage well-being. But the value of the coefficients of Free Love × MarryAge > 7 is smaller than Free Love × MarryAge3–7.

Free Love marriage after 1–2 years is the most harmonious period. However, after 3–7 years of marriage, it is inevitable that there will be mutual frictions in daily life, and the well-being decreases. But after 7 years of marriage, this kind of romantic relationship becomes very stable, and the well-being in turn increase.

In terms of personal characters, the coefficient of Free Love × Confidence is significantly positive at the 5% level. Residents who have more confidence in the future are inclined to see the brightness of life after Free Love marriage (Yoo, 2005), and they are more likely to hold a persistently optimistic attitude toward creating well-being for each other. The coefficient of Free Love × Money is significantly negative at the 10% level. Residents who overemphasize money also reflect a heavy burden of life to some extent. Therefore, the effect of way of love on after-marriage well-being will decrease due to the overemphasis on money.

In addition, residents of different generations, family structures, and urban and rural areas often have different attitudes toward marriage types and marriage satisfaction, which will be discussed separately in this paper.

People of different generations tend to have different attitudes toward types of marriage and marital satisfaction. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 4 are the results of heterogeneity analysis among age groups. Compared with the post-60s and post-70s, the impact of the reform and opening-up tide in the post-80s is more open-minded and the living conditions are relatively better. At the same time, for love, young people will pursue the other's feelings and romance.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Age40–50 | Age30–40 | Age20–30 | Have Child | No Child | Rural | Urban |

| Free Love | 0.1162** | 0.1273** | 0.1065** | 0.5054* | 0.1154** | 0.1116** | 0.1537 |

| (0.0483) | (0.0501) | (0.0474) | (0.2659) | (0.0501) | (0.0530) | (0.0976) | |

| Post-60s × Free Love | 0.0643 | ||||||

| (0.1246) | |||||||

| Post-70s × Free Love | 0.0083 | ||||||

| (0.1078) | |||||||

| Post-80s × Free Love | 0.2538* | ||||||

| (0.1500) | |||||||

| Post-60s | −0.1355 | ||||||

| (0.1238) | |||||||

| Post-70s | −0.0019 | ||||||

| (0.1067) | |||||||

| Post-80s | −0.2159 | ||||||

| (0.1502) | |||||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.0297 | 0.0294 | 0.0295 | 0.0767 | 0.0311 | 0.0328 | 0.0262 |

| Observations | 16,165 | 16,165 | 16,165 | 592 | 9831 | 8307 | 7858 |

- Note: Post-60s refers to the age between 40 and 50 years old; Post-70s refers to the age between 30 and 40 years old; Post-80s refers to the age between 20 and 30 years old. The age is compared to the survey year 2010. Robust standard error in brackets. Province is a province dummy variable.

- ***, **, and * are significant at the level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Columns (4) and (5) of Table 4 show the heterogeneity analysis results of whether married couples have children or not. We found that, whether there are children or not, free love significantly improves couples' well-being compared with arranged marriage. This means that different family structures (such as whether there are children or not) are still robust for the result of this paper. In other words, a larger proportion of married couples with children have experienced arranged marriages, and they may bear more fertility pressure from parents or other family members.

Columns (6) and (7) of Table 4 show the results of urban and rural heterogeneity analysis. The results show that free love has a positive impact on couples' well-being in both rural and urban areas. In rural areas, compared with arranged marriage, free love has a more significant impact on improving couples' well-being, but this difference has no significant impact in urban areas. The possible reason is that the “two-way asymmetric flow” between urban and rural areas makes the “dualistic structure system of urban and rural areas” in the marriage world more stable. Compared with rural areas, Chinese urban residents and their parents generally have pensions and medical insurance, and they don't rely too much on their children in providing for the aged, so their parents won't interfere too much no matter whether their children choose free love or parents arranged. However, in rural areas, various safeguard measures are relatively weak, which makes the marriage arranged by parents subject to more interference, thus having more negative effects on children's well-being.

4.4 Mechanism analysis

As mentioned above, compared with arranged marriage, free love can better promote after-marriage well-being. But the reason behind it is still unknown, hence we need to further explore the way that way of love affects the well-being of married residents from the perspective of personal thoughts and family concepts. In Table 5, interaction with others, closeness with the spouse, satisfaction with the family, and reproduction willingness are selected as the proxy variable on the level of personal thoughts. These four variables are all ranked indicators of numbers 1–5: from small to high means from not very important to very important.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction | Closeness | Satisfaction | Reproduction | |

| Free Love | 0.1663*** | 0.0889* | 0.0865* | −0.0936* |

| (0.0478) | (0.0495) | (0.0509) | (0.0498) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 16,139 | 16,165 | 16,165 | 16,165 |

- Note: Robust standard error in brackets. Province is a province dummy variable.

- ***, **, and * are significant at the level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

The reasons for choosing these proxy variables are: (1) We investigate married residents, and find that the influence of the way of love on residents' well-being is closely related to their personal ideas after marriage. (2) The ability to get along with others, represents the residents' personal ideas of openness and inclusiveness, and is also an important way to promote well-being. (3) Residents who have a close relationship with their spouse expect a happy and harmonious family and are more likely to promote well-being after marriage. (4) The emphasis on procreation may cause more mental pressure and reduce subjective well-being (Camfield et al., 2009).

It can be seen from Table 5 that free love marriage could significantly promote married residents' ability to get along with others, lift their closeness with the spouse, increase the satisfaction of the family and alleviate reproduction willingness. To some extent, the residents of free love could soften their mental pressure of traditional reproduction thoughts and thus contribute to their after-marriage well-being.

5 CONCLUSION

To empirically test the effect of way of love on after-marriage well-being, we employ 2010 China Family Panel Studies and use Ordered Probit, Instrumental Variables, and Conditional Mixed Process to analyze the effect. The findings are: (i) Compared with arranged marriage, free love could significantly increase the well-being of married residents. (ii) The promotion effect of free love on well-being is more obvious 2 years after marriage and residents with positive personal values, in the post-80s, and rural areas. (iii) In mechanism analysis, married residents met through free love will significantly increase their ability to get along with others, increase their intimacy with their spouses, improve family harmony, and reduce their emphasis on family succession, thus further enhancing their well-being.

The main implications of this paper are as follows: First, the results of this paper show that, compared with arranged marriage, free love significantly improves the well-being of married residents. Arranged marriage is a multidimensional intervention by parents on marital life issues such as mate selection, wedding planning, economic property, children's birth education, and marital relations. Due to the lack of emotional foundation, arranged marriage will often bring both husband and wife a certain amount of mental pressure. Hence we should respect personal preferences and give lovers more freedom of choice in the marriage market.

Second, we also prove that residents' ability to get along with others will significantly increase after marriage well-being through the way of free love, their intimacy with their spouse will be increased, their family harmony will be improved, and their emphasis on family succession will be reduced. It also tells us that couples who meet through free love are more responsible for their families, and pay more attention to spiritual needs than material couples.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Bowen Li: Writing – original draft; writing – review & editing. Cai Zhou: Methodology; software. Ji Luo: Supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, the participants in the 2020 International Symposium on Contemporary Labor Economics for their useful discussions, the data of China Family Panel Studies supported by Peking University, and the effective suggestions of Zhang Sisi, Li Changhong of Jinan University and Wu Yiping of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

APPENDIX A:

(see Table A1–A3)

| How do you meet your spouse/partner | 2018 | 2016 | 2014 | 2012 | 2010 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | |

| Meet at school | 221 | 5.7 | 194 | 5.3 | 171 | 4.4 | 302 | 5.6 | 753 | 2.8 |

| Meet at workplace | 516 | 13 | 511 | 14 | 440 | 11 | 773 | 14 | 2400 | 8.9 |

| Meet at residence | 292 | 7.6 | 293 | 8.0 | 310 | 7.9 | 313 | 5.9 | 1825 | 6.8 |

| Friend introduction | 957 | 24 | 930 | 25 | 950 | 24 | 1422 | 26 | ||

| Matchmaking introduction | 108 | 2.8 | 115 | 3.2 | 63 | 1.6 | 168 | 3.1 | 990 | 3.7 |

| Arranged marriage | 133 | 3.4 | 142 | 3.9 | 186 | 4.8 | 153 | 2.9 | 1174 | 4.4 |

| Meet by Internet | 40 | 1.0 | 34 | 0.9 | 20 | 0.5 | 59 | 1.1 | 57 | 0.2 |

| Others | 70 | 1.8 | 49 | 1.3 | 47 | 1.2 | 82 | 1.5 | 459 | 1.7 |

| Total | 3875 | 100 | 3655 | 100 | 3884 | 100 | 5346 | 100 | 26,722 | 100 |

| Variable names | Variable definitions |

|---|---|

| Explained variable | |

| Well-being | Very unhappy—1–2–3–4–5—very happy |

| Key variables | |

| Free Love | “How do you know your spouse?” In this paper, the value of free love is 1 (meet at school, meet at work, meet in residence, meet in other places, meet through relatives, meet through friends, meet through marriage agency, meet through the Internet), and the value of parents' arranged marriage is 0. |

| Control variables | |

| Gender | Male = 1, female = 0 |

| Age | Actual age calculated according to the survey year, unit: age |

| Age2/100 | In order not to make the order of magnitude |

| Hukou | Your current hukou status is (agricultural hukou = 1, others = 0) |

| Han | May I ask if your ethnic composition is (Han = 1, others = 0) (the one registered on the household register shall prevail) |

| PartyMember | Which organizations do you belong to (Party member = 1, others = 0) |

| Education | Your education level (junior college or above = 1, others = 0) |

| Health | Health status of respondents (health = 1, others = 0) |

| Income | Last year, your total personal income was (yuan) |

| Work | Do you have a job now? (There is = 1, there is no = 0) |

| InternetUser | Excuse me, do you use the Internet? (Yes = 1, no = 0) |

| FamilySize | How many people are there in your family?(Employer: Person) |

| Instrumental variables | |

| The sex ratio of unmarried groups in 1996 | Unmarried male population to female Population in 1996 (×100) |

| The urbanization rate in 1964 | The ratio of urban population to total population in 1964 |

| Variable | Full sample (N = 16,165) | Free love (N = 15,545) | Arranged marriage (N = 620) | SE (mean) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Difference | |

| Well-being | 3.8471 | 0.9984 | 3.8565 | 0.9979 | 3.6129 | 0.9838 | 0.2436*** |

| Free Love | 0.9616 | 0.1921 | |||||

| Gender | 0.4859 | 0.4998 | 0.4871 | 0.4998 | 0.4565 | 0.4985 | 0.0307* |

| Age | 47.0727 | 13.3283 | 46.7839 | 13.1611 | 54.3145 | 15.3137 | −7.5307*** |

| Age2 | 23.9347 | 13.1814 | 23.6193 | 12.9284 | 31.8420 | 16.5772 | −8.2237*** |

| Hukou | 0.7094 | 0.4540 | 0.7022 | 0.4573 | 0.8903 | 0.3127 | −0.1881*** |

| Han | 0.8972 | 0.3036 | 0.9058 | 0.2922 | 0.6839 | 0.4653 | 0.2219*** |

| PartyMember | 0.0849 | 0.2787 | 0.0856 | 0.2797 | 0.0677 | 0.2515 | 0.0178 |

| Education | 0.0624 | 0.2418 | 0.0646 | 0.2458 | 0.0065 | 0.0801 | 0.0581*** |

| Health | 0.7603 | 0.4269 | 0.7676 | 0.4224 | 0.5790 | 0.4941 | 0.1885*** |

| Income | 6.3326 | 4.1632 | 6.3445 | 4.1827 | 6.0329 | 3.6287 | 0.3116* |

| Work | 0.5382 | 0.4986 | 0.5401 | 0.4984 | 0.4903 | 0.5003 | 0.0498** |

| InternetUser | 0.1276 | 0.3336 | 0.1320 | 0.3385 | 0.0161 | 0.1261 | 0.1159*** |

| FamilySize | 4.2471 | 1.7901 | 4.2235 | 1.7738 | 4.8371 | 2.0755 | −0.6136*** |

REFERENCES

- 1 “Have you ever regretted getting married?” asked by the 2018 China Marriage Happiness Power Index Research Report. About 63.3% of couples have regretted their marriage.

- 2 According to the 2018 China Marriage and Love Happiness Index Research Report, the happiness index of arranged marriage and love is 75.3 points, while the happiness index of free marriage and love is 79.2 points, which is significantly higher than arranged marriage and love.

- 3 TGI index = the proportion of groups with certain characteristics in the target population/the proportion of groups with the same characteristics in the population × standard number 100. TGI index represents the difference of users' attention to problems with different characteristics. TGI index equals to 100 indicates the average level, while higher than 100 indicates that users of this type pay more attention to certain problems than the overall level.

- 4 Specifically, as mentioned in the questionnaire, “How do you know your spouse?” In this paper, the value of free love is 1 (meet at school, meet at work, meet in residence, meet in other places, meet through relatives, meet through friends, meet through marriage agency, meet through the Internet), and the value of parents' arranged marriage is 0.

- 5 According to the 2018 China Marriage and Love Happiness Index Research Report, the happiness index of arranged marriage and love is 75.3 points, while the happiness index of free marriage and love is 79.2 points, which is significantly higher than arranged marriage and love.

- 6 The data from China's macroeconomic database in 1996 is a relatively early macroeconomic variable that can be collected.

- 7 The data from the 1964 China Census.

- 8 See the Table A1 for details.

- 9 CMP is applicable to two types of models: (1) The model of recursive data generation process is established. (2) It is simultaneous, but a set of recursive equations can be constructed by means of instrumental variables, such as two-stage least square method, which can be used to estimate the structural parameters uniformly in the final stage.