Investigating whether connecting people can promote subnational economic development: Evidence from China–ASEAN friendship cities

Abstract

Whether maintaining a close relationship with China can benefit economic performance in the postpandemic era is a crucial concern for countries around the world. This study employs the difference-in-difference (DID) model and propensity score matching to estimate the impact of connecting people proposed by the Belt and Road Initiate (BRI) on the subnational economic development of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) cities. The quasi-natural experiment of DID is based on the establishment of China–ASEAN friendship cities. We capture the ASEAN subnational economic development by calibrated satellite nighttime light data. Our findings show that the establishment of a friendship-city relationship has a positive impact on the subnational economic development of China–ASEAN cities. Further analysis indicates that bilateral trade, China's direct investment in contracted projects, and mutual visits by national leaders may be the underlying channels for boosting the economic development of China–ASEAN friendship cities. This study contributes to the literature on friendship city and provides ex-ante implications on the BRI from the perspective of connecting people with first-hand empirical evidence.

1 INTRODUCTION

There have been unforeseen challenges since 2020, ranging from the significant impact of the pandemic on the global economy, racism campaigns, and the China–US trade war. These have also fueled antiglobalization sentiments in some economies, resulting in a re-discussion of economic integration and cooperation. However, it is infeasible to promote human civilization and preserve sustainable development through noncooperative global governance in the face of unanticipated challenges. China advocates the path of inclusive globalization that emphasizes a community of shared future for mankind by seeking common ground while reserving differences and cooperating in many fields to achieve an all-win benefit (Liu & Dunford, 2016). One of the representative proposals that reflect China's value of sustainable international cooperation is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). BRI calls for an open and inclusive pattern of sustainable international economic, political, and cultural cooperation and development through multiple types of increased connectivity, including promoting policy coordination, connectivity of infrastructure and facilities, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and closer people-to-people ties1 (Xi, 2013). Yet, important questions arise on the long-term socioeconomic connectivity of the initiative within BRI countries, and how the Chinese government will position itself on connectivity sustainability. The initiative of connecting people and creating closer people-to-people ties stands out among the five dimensions of connectivity. International people-to-people ties could take place both at the macro and micro levels. First, for instance, in terms of national cooperation, Premier Zhu Rongji and the leaders the of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries signed the framework agreement on economic cooperation in November 2002 at the Sixth China–ASEAN leaders' meeting, which resulted in the completion of the China–ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA) in 2010. CAFTA is the most populous and the largest free trade area composed of developing countries, and it makes consistent contributions to the economic development of Asia and the world. In early 2020, ASEAN became China's first large trade partner, and China has been the biggest trade partner of ASEAN for a decade.2 In October 2013, during his visits to Indonesia and Malaysia, President Xi Jinping delivered a speech about the initiative of “building a China–ASEAN community with a shared future,” while emphasizing the significance of the China–ASEAN relationship.

Second, globalization has resulted in a substantial increase in people-to-people interactions at top-down levels, regardless of national borders. This has further resulted in subnational entities that enhance international engagement by conducting city diplomacy. Friendship city is the most representative form of city diplomacy under the framework of national diplomacy. It refers to a stable diplomatic relationship between international subnational entities, such as provinces, districts, states, prefectural cities, and counties, to promote city development. This kind of relationship, which is achieved through friendship city exchange activities before the formal signing of the cooperation agreement, is aimed at promoting cooperation in various fields, and enhancing the folk emotions between the residents of the friendship cities. Consistent with the above definition, the city entities involved in this study refer to subnational administrative divisions covering the provincial, district, and municipal levels. Regarding subnational communication, China and ASEAN countries began to establish connections of city diplomacy in 1992. In August 1992, Beijing and Jakarta of Indonesia established an agreement on the friendship-city relationship. Consequently, more connecting-people cooperation between the friendship cities in the fields of tourism, health, sports, and youth exchange started to flourish.

The root of the friendship city phenomenon can be traced back to the aftermath of the Second World War, a period of emotional healing after the destructive disaster. There are slightly different appellations of city-to-city ties around the world. Close city-to-city ties are referred to as “Twin City” in Britain, and in some European countries, “Brother City” in Russia, and “Sister City” in the United States and Japan. Premier Zhou Enlai refer to as “Friendship City” to express the equality between both cities when China established the first pair of friendship cities (Tianjin, China and Kobe, Japan). In this study, we refer close city relationships collectively as Friendship City for the unity of concept. China has experienced decades of flourishing development of friendship-city relations. China established its first pair of friendship cities and the China International Friendship City Association for international friendship city management in 1973 and 1992, respectively. By the second quarter of 2018, China had established 2453 pairs of friendship cities with 136 countries worldwide, while the number of friendship cities with Asian countries accounted for about 33%. While it is a global topic that requires comprehensive investigation, researchers are ignorant of basic subnational interaction and have paid little attention to the economic impact of friendship city. Moreover, the relevant empirical studies focusing on foreign local development with subnational-level statistics are still scarce. Therefore, this study is motivated to bridge this gap by investigating whether friendship-city relations can benefit subnational economic growth through remote sensing data.

This study uses ASEAN as the research sample because ASEAN remains in in-depth connectivity with China among the countries of the BRI (Yu et al., 2010). More importantly, ASEAN maintains a pivotal hub of the BRI in both trade and investment cooperation with China. First, in terms of a general evaluation of bilateral cooperation, we obtain the international cooperation index of BRI countries during 2016–2018 from the Belt and Road Big Data Report published by the State Information Center which is affiliated to the National Development and Reform Commission.3 The index values of sample ASEAN countries4 and average values of BRI countries are shown in Table 1. The international cooperation index is a comprehensive appraisal of the five connectivities of BRI construction based on five dimensions of policy dialog, infrastructure connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial support, and people-to-people connectivity. A greater index value represents a higher degree of bilateral cooperation in the above five dimensions. According to Table 2, the bilateral cooperation index of each sample ASEAN country is higher than the average value of BRI countries, indicating that ASEAN countries enjoy long-run and in-depth cooperation with China in comparison with the average level of BRI countries.

| Country | Correlation coefficients | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before calibration | (2) After calibration | (3) Before calibration | (4) After calibration | |

| Cambodia | 0.8057a | 0.8961a | 0.5586 | 0.8644 |

| Indonesia | 0.2293a | 0.9992a | 0.6194 | 0.9166 |

| Laos | 0.9003a | 0.9852a | 0.7837 | 0.9559 |

| Malaysia | 0.2443a | 0.9812a | 0.7941 | 0.9574 |

| Myanmar | 0.6247a | 0.9334a | 0.2425 | 0.9040 |

| Philippines | 0.2548a | 0.9987a | 0.7295 | 0.8328 |

| Thailand | 0.2636a | 0.9993a | 0.5483 | 0.8942 |

| Vietnam | 0.3364a | 0.9969a | 0.4119 | 0.8343 |

- a Pearson's correlation coefficients that are significant at the 1% level.

| ASEAN countries | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | 60.98 | 70.17 | 68.46 |

| Indonesia | 71.33 | 70.70 | 69.86 |

| Laos | 65.98 | 64.81 | 67.07 |

| Malaysia | 69.89 | 70.91 | 72.71 |

| Myanmar | 61.43 | 60.99 | 63.49 |

| Philippines | 46.33 | 53.15 | 58.84 |

| Thailand | 74.01 | 74.74 | 73.82 |

| Vietnam | 70.74 | 72.21 | 75.25 |

| Average value of BRI countries | 43.55 | 45.11 | 47.12 |

- Abbreviations: ASEAN, Association of Southeast Asian Nations; BRI, Belt and Road Initiative.

- Source: State Information Center–The Belt and Road big data report (2016–2018).

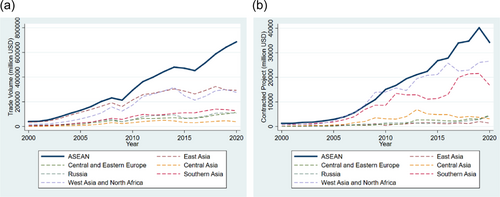

Furthermore, ASEAN countries continue playing an active and predominant role in economic cooperation with China in comparison with other BRI countries. We collect statistics about the number of China's import and export and investment in contracted projects with 65 BRI countries from China's National Bureau of Statistics. We divide the BRI countries into seven regions based on the category of Belt and Road Research Database of CSMAR, including ASEAN, East Asia, Central, and Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Russia, Southern Asia, and West Asia and North Africa. The BRI countries category is reported in Table A2.

The left picture of Figure 1 demonstrates China's trade volumes along with BRI countries, while China's economic cooperation in completed contracted projects with BRI countries is shown in the right picture of Figure 1. Both trade volumes and contracted projects in ASEAN and non-ASEAN regions rose over the period shown, but the figures for ASEAN were significantly higher. The international trade volume of China–ASEAN countries increased sharply from 39,521.51 million USD in 2000 to 292,903.59 million USD in 2010. And the number hit 685,504.81 million USD in 2020, more than twice that of 2010. Whereas, the largest trade volume of other BRI regions peaked at 323,818.75 million USD in 2018, which accounts for about half the amount of the ASEAN in the same year (323,818.75/587,739.5). Second, the contracted projects of China–ASEAN countries were worth 1252.27 million USD in 2000, and rose to 15,083.8 million USD in 2010 when ASEAN started to become the largest partner of China's foreign contracted projects. And the number hit 40,190.8 million USD in 2019, more than two and a half times that of 2010.

To sum up, the ASEAN region is an important cooperation partner in both trade and investment in contracted projects. Under such circumstances, ASEAN countries are representative examples of BRI regions for examining the micro-level economic effect of China–ASEAN friendship-city relations.

To proxy the subnational people-to-people connectivity, we compile friendship city-pairing data between China and ASEAN countries from 2000 to 2013, including Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos. Our sample period covers the data before 2013 because the latest nighttime light data of Defense Meteorological Satellite Program's Operational Line-Scan System (DMSP–OLS) is not available since 2013, and the new source of NPP-VIIRS nighttime light data only covers the years since 2012. Note that these two sources are not comparable due to different sensors and lack of unified on-board calibration. Nevertheless, the examination of subnational economic performance before 2013 can exclude the confounding influence of the BRI launch. This means that such estimation represents the lower bound of the friendship city effect because the launch of BRI would enhance bilateral economic cooperation since 2013.

Based on the establishment of friendship-city data, we construct a quasi-natural experiment in which difference-in-difference (DID) and propensity score matching (PSM) methods are used to estimate the economic effect of friendship-city relationships. The difficulty of examining the subnational economic effect on ASEAN countries is the dearth of economic statistics. For example, the General Statistics Office of Vietnam5 discloses nationwide statistics while the city-level statistics of Vietnam covering our sample period are not available. Likewise, this issue of lacking subnational economic statistics exists in other ASEAN countries. Therefore, it is hardly feasible to obtain conventional subnational economic development indicators for ASEAN countries. To fill this gap, we collect city-level data from remote sensing data sets to capture regional economic development and match it with the friendship city-pairing data from the International Friendship City Association. By documenting a set of intact city-level indicators of ASEAN cities, our findings suggest that the establishments of friendship-city relationships significantly promote the regional economic development of China–ASEAN friendship cities. This profound impact is transmitted through the channels of bilateral trade, China's direct investment in contracted projects, and national leaders’ mutual visits.

The marginal contributions of this study are as follows. First, we contribute to the current literature by providing the first empirical study examining the impact of friendship-city relations with China on regional economic development. Second, this study sheds light on whether and how friendship city establishment influences subnational economic development, and supplements prior literature on diplomatic relations and economic development at the city level. Third, we present novel evidence of economic outcomes of connecting subnational entities in developing countries from outer space by combining remote sensing data sets with econometric estimation. Hence, this study provides implications for the goal of connecting people proposed by the BRI.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

In this section, we develop the theoretical logic of our study based on a literature review of diplomatic relations and regional economic development to propose our hypotheses.

2.1 Political relations and regional economic development

Most related studies focus on political relationships with the state as a subject engaging in economic or social activities. For instance, diplomatic stability is a significant determinant of international trade, investment, and various channels of people-to-people communication.

First, under the current complex domestic and international economic circumstances, the quality of bilateral political relations significantly affects the trade flows of the countries involved. Pollins (1989) documents theoretical evidence of the significant effects of diplomacy on import levels. Acemoglu and Yared (2010) suggest that the openness and policies of international trade, finance, and technology are embedded in political decisions. Meanwhile, prior studies suggest an affirmative conclusion, indicating that the country with lower barriers or more liberalized trade regimes experiences a higher annual growth rate (Frankel & Romer, 1999; Wacziarg & Welch, 2008). International trade is one of the most important driving forces of national wealth (Irwin & Terviö, 2002; Noguer & Siscart, 2005), and unimpeded trade should be a significant channel for the friendship city to prospect. However, data on city trade volume in developing countries are not currently accessible. Additionally, bilateral geographic distancing reflects transaction costs, such as those of transportation and logistics. Consequently, geographic proximity equals an important trade advantage (Anderson & Wincoop, 2003; Giuliano et al., 2014). Therefore, we further use geographic distance as an alternative proxy for trade cost to investigate whether the trade channel can enhance the association between friendship-city relationships and subnational economic development.

Second, previous studies indicate that direct investment is also an influence channel of political or diplomatic relations. Sun and Liu (2019) document international data on China's diplomatic partnership strategy and find a positive impact on the outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) of Chinese firms. Du and Zhang (2018) find that China's state-own firms played a leading role in infrastructure sectors of Chinese overseas direct investment in response to the BRI. A friendly political relationship between the host country and the home government has a significant positive impact on OFDI, while political conflicts between the two countries inhibit investment cooperation (Biglaiser & DeRouen, 2007; Li & Vashchilko, 2010). Friendship-city ties have also built a communication platform for bilateral economic cooperation, hence reducing the transaction cost of foreign investment through diversified business activities and improving the decision-making and implementation efficiency of investment behavior (Büthe & Milner, 2008). In particular, the capacity and expertise of China's infrastructure in international cooperation and development is the most important feature distinguishing the BRI from many other international cooperation mechanisms. This is important because China experienced a significant investment in infrastructure that facilitated rapid economic growth, while some of the BRI countries have underinvested in infrastructure (Huang, 2016; Lu et al., 2018). Given the comparative advantage of China, the promotion of China's foreign contracted projects in infrastructure is the key element of bilateral cooperation. In fact, China's foreign contracted projects business covers more than 100 countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe. As an important form of foreign economic cooperation, foreign contracted projects have been an international strategy for Chinese firms since China's reform and opening. Therefore, the establishment of friendship cities can also promote regional economic upgrades through the cooperation of foreign contracting projects.

Third, the establishment and subsequent upgrade of friendship-city relationships involve bilateral communication and mutual visits by citizens and national leaders. State visits by national leaders are the highest form of foreign exchange between the two countries. Further, it can improve bilateral trade (Nitsch, 2007). Among the different forms of visits, the economic effect of Chinese leaders' visits on trade and investment is more significant than that of the leaders of the host countries (Yan et al., 2019; J. Zhang et al., 2011). In sum, bilateral leader visits can reinforce the linkage effect of friendship-city relationships on economic development among economies.

2.2 Friendship city and people-to-people connectivity

Friendship city is the most fundamental form of city diplomacy, which is an important component of people-to-people connectivity in the BRI. A pair of friendship cites represent the partnerships established by cities of different countries to develop stable relations based on the mutual understanding of each other's society and culture, and the need to promote mutual economic and trade ties (Amiri & Sevin, 2020; Tang, 2015). In contrast to the diplomatic paradigm that the subject is referred to as the state, the subject of city diplomacy is city entities that establish and implement agreements with foreign counterparts. Such agreements consist of long-term cooperation in fields such as education, culture and health, youth exchanges, politics, economy, and science, thereby highlighting the role of subnational governments in global engagement (Zelinsky, 1991). Zhao (2014) and Chen et al. (2020) argue that the initial orientation of China's city diplomacy focuses on building people-to-people bonds; it has, however, shifted to a practical direction related to economic and social interests since the 21st century and has become a significant driving force for economic cooperation between cities. There are various activities related to commercial communications on the platform of friendship cities. For instance, Beijing Foton Motor signed the Jakarta new energy bus cooperation agreement with the Indonesian public transport authorities and Jakarta public transport department in 2014.6 The subnational economic cooperation is still thriving despite the pandemic challenges. For example, the Finnish chamber of commerce entrepreneur delegation was invited to the investment of construction in Beijing for industry-oriented communication in 2021.7

Furthermore, Baycan-Levent et al. (2010) show that the existence of any former relationship, economic benefit, and city characteristic similarity affect the success of establishing a friendship-city relationship. And Baycan-Levent et al. (2008) find that both sides of European friendship cities enjoy an increase in investment growth through a small-sample questionnaire survey. Albeit an intriguing question to the international community, there are few empirical studies to analyze whether friendship-city relations have generated real effects on emerging economies. Although Chen et al. (2020) and Y. Zhang et al. (2020) have provided national evidence that the establishment of a friendship- city relationship can significantly promote the export volume of Chinese products and China's overseas investment, and Tong et al. (2020) have discussed the Chinese firm-level export to the BRI countries from a perspective of China's soft power, their studies only focused on the perspective of China's interest. Whereas, literature or empirical evidence of the economic impact on counterparts, especially on the subnational entities remains scarce. From the arguments of the above viewpoints, the steady development of the city-to-city relationship is not only beneficial to cultural exchanges but also facilitates economic activities for both sides. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses.

- Hypothesis H1: The establishment of a friendship-city relationship can promote regional economic development.

- Hypothesis H2: The underlying channels of the impact of a friendship-city relationship include bilateral trade, direct investment, and mutual visits by national leaders.

3 DATA, VARIABLES, AND ESTIMATION MODEL

3.1 Nighttime light data

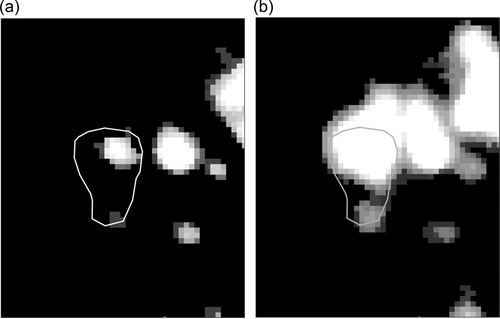

Since the National Geophysical Data Center released the nighttime stable light data from DMSP/OLS Nighttime Lights Time Series data set, an increasing number of economists have begun to use this big data of nighttime light to evaluate regional economic activity. The digital number values (i.e., the DN value) derived from satellite images ranging from 0 to 63 directly reflect the regional nighttime light brightness, which offsets the lack of economic development record in underdeveloped areas (Donaldson & Storeygard, 2016; Henderson et al., 2012; Michalopoulos & Papaioannou, 2014). Henderson et al. (2012) have provided a systematic verification that the DN value derived from the nighttime light data set is supplementary and a useful proxy for conventional socioeconomic statistics such as GDP growth in developing countries and subnational regions. For instance, the mean value of DN extracted from DMSP/OLS provides a proxy of African regional economic development to identify the influences of institutional factors (Michalopoulos & Papaioannou, 2014). We extract ASEAN city-level light data using global DMSP/OLS nighttime light images and the light changes of sample images of Naypyidaw, the capital city of Myanmar are shown in Figure A2. However, satellite sensors can be affected by factors, such as atmospheric absorption and scattering, deteriorated air quality, and worn-out equipment, which means that the original data cannot be used directly due to issues, such as abnormal fluctuations, top-coded pixels, and time discontinuity. Therefore, a series of calibrations are necessary to ensure the reliable application of light data. In this study, we follow two threads of research, including the remote sensing literature (Cao et al., 2015; Elvidge et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012) and economic literature (Liu et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2015), to calibrate raw nighttime data. We follow their three-step calibration method to convert the raw data sets into a comparable and continuous time-series data set. Specifically, the entire calibration process includes intersensor, averaging, and intrasensor calibration, and the corresponding changes in total DN values and numbers of lit pixels are demonstrated in Figure 1.

Given that the DMSP/OLS nighttime light data sets have been updated to 2013, we can obtain nighttime light images from five satellite sensors during the period between 1998 and 2013: F12 (1998–1999), F14 (2000–2003), F15 (2000–2007), F16 (2004–2009), and F18 (2010–2013), for a total of 24 stable average light images. It should be noted that the images from the extended years of 1998–1999 serve to be the benchmark for subsequent years for intra-sensor calibration because the intrasensor calibration is a recursive calculation that may result in a lack of benchmark for data from the year 2000.

The independent variable is the DN value of pixel j within the invariant target region s in the radiance-calibrated image of 2006 from global radiance-calibrated nighttime lights.9 The dependent variable is the original DN value of pixel j in the same target region s from 24 light images in year t. Estimated parameters , , and model R2 values of Equation (1) are reported in Table A1.

Parameters and are then incorporated into Equation (2). represents the DN values of pixel j in year t after intersensor calibration. from the right-hand side of the equation represent the original DN values before calibration. After the calibration of Equation (2), the brightness of different satellites and different pixels in different years are re-adjusted based on a common standard, making the DMSP/OLS nighttime light data sets comparable. After intersensor calibration, the top-coded limit of the DN value is further eliminated.

Through the above three-step calibration, the issues of DN value fluctuation of unstable pixels and abnormal values are effectively alleviated. Accordingly, we extracted the average DN values of ASEAN cities from the calibrated data set as a proxy for subnational economic development.

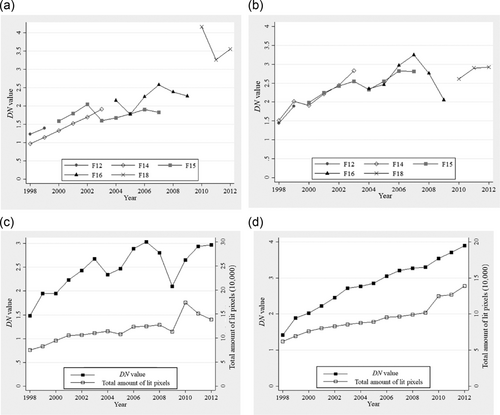

3.2 Validation of calibration

As it is inaccessible to gain city-level economic statistics of ASEAN countries, we first use Vietnam as an example to illustrate the three-step calibration process in this section. Specifically, we present the pixel-level DN changes and the total amount of lit pixels extracted from Vietnam during the whole calibration process in Figure 2. Figure 2a shows the DN average values of different satellites and years separately before calibration. There are overlaps of DN values and a sharp leap in 2010 due to extreme outliers according to Figure 2a. Therefore, without any calibration, the raw datasets cannot be directly utilized to extract time-series statistics. Figure 2b shows the DN values after inter-sensor calibration. Through inter-calibration, the pixels of different satellite becomes comparable based on the same scale. Figure 2c-d illustrates both average DN values and the total amount of lit pixels after averaging and intra-sensor calibration respectively. As can be seen from Figure 2d, the calibrated nighttime light image exhibits comparable continuity in both DN values and lit pixel numbers, which is an important foundation before applying for fine-level economic research.

Then, we derive total DN values of sample ASEAN countries from raw data and calibrated data and obtain two sets of correlation coefficients between DN value and real GDP adjusted by a constant dollar of 2010. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 1 report the before- and after-calibration results in terms of data correlation, respectively. It is clear that both before- and after-calibration results exhibit a significantly positive correlation, which indicates the rationality basis of using nighttime light data to proxy economic development. Nevertheless, the correlation coefficients of before-calibration in column (1) for most countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand are lower than 0.3. On the contrary, the correlation coefficients of after-calibration in column (2) are larger than 0.89 with a maximum value exceeding 0.99, which all present higher values than before-calibration in column (1). In brief, the correlation tests validate the calibration results of raw data.

Furthermore, we use a simple OLS model to examine the overall fitted value (R2) of nighttime light data and GDP data at the country level. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 1 show the R2 values before and after the calibration, respectively. All of the R2 values of ASEAN countries are greater than 0.83 with a maximum value reaching 0.9574 after the calibration, while each R2 value is less than 0.8 before calibration. In sum, through the comparison of the before- and after-calibration results, the three-step calibration of DN value is valid and applicable for fine-level ASEAN study.

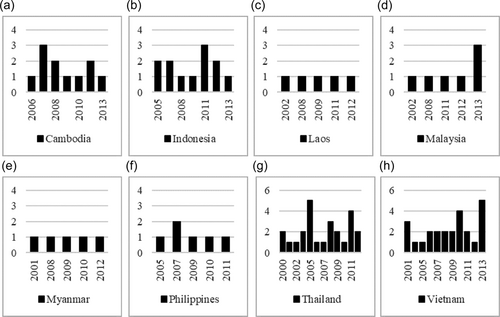

3.3 Establishment data of friendship city

We collect paring data of China–ASEAN friendship cities from 2000 to 2013 from the website of the China International Friendship City Association. The sample size is 101 pairs of friendship cities (Figure 3). The total number of friendship cities varies in different countries. Thailand and Vietnam ranked the top in the establishment of China–ASEAN friendship cities from 2000 to 2013. In all, the growth trend of establishing the China–ASEAN friendship-city relationship remains steady, indicating the development potential of connecting people-to-people bonds.

We use the establishment year of a friendship city as the policy shock in the DID model to examine whether and to what extent subnational economic growth responds to the friendship-city relationship. In general, we define an indicator FriendshipCity equals 1, if the city establishes a friendship-city relationship with China in year t and afterward, and 0 otherwise.

However, it should be noted that among all China–ASEAN friendship-city relations, 60.2% of the ASEAN friendship cities belong to second-level administrative divisions (cities), while 39.8% of the friendship cities belong to first-level administrative divisions (provinces). For instance, there are friendship-city pairs like Xiamen (China)–Surabaya (Indonesia), Nanning (China)–Haiphong City (Vietnam), and friendship-province relations, such as Hainan Province (China)–Quang Ninh Province (Vietnam), Yunnan Province (China)–Bali Province (Indonesia), and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (China)–Prey Veng Province (Cambodia) in our sample.

In the former case, the friendship-city relationship is established at the city level, which is the second-level administrative division of a country. It is straightforward that for a second-level administrative division that has established friendship-city relations, the corresponding city is defined as 1, and 0 otherwise because most of the second-level administrative divisions of ASEAN countries are cities. However, the latter example of a friendship-city relationship between bilateral provinces is a relationship of friendship province. Regarding the friendship-province relationship, we define two variables City and Prov to better distinguish the friendship-province effect. For instance, there is a friendship-province relationship between Yunnan Province (China) and Bali Province (Indonesia) in 2003. In the situation, the variable City equals 1 for the capital city Denpasar; while Prov equals 1 for all nine cities of Bali Province, including Denpasar, Klungkung, Jembrana, Tabanan, Gianyar, Karangasem, Badung, Buleleng, Bangli city.

In sum, for variable City, only the provincial capital city of the first-level administrative divisions (province) that established the friendship-city relations is defined as 1, and 0 otherwise. Second, for variable Prov, all subordinate administrative divisions, that is, all cities in the province are defined as 1, and 0 otherwise. In this case, the coefficient of City reflects ASEAN capital-city-level interaction while the coefficient of Prov reveals the effect of all cities’ economic development within the same “friendship province.”

We set the division between provincial capital cities and all cities for the following reasons. First, the provincial capital city, as the economic center of the province, is regarded as a representative of the economic development of a province. If the friendship-city relationship is established with a province, such an economic impact would naturally have a primary effect on the capital city. However, can this influence radiate from the provincial capital city to all cities within the same friendship province? We attempt to answer this question by constructing the variable of Prov to investigate whether the establishment of a friendship province has a “global effect” that covers the entire friendship province. According to the above hypothesis, we expect the coefficient of City/Prov to be significantly positive, indicating that friendship-city relationships can promote the economic development of ASEAN friendship cities.

3.4 Control variables at city level

3.5 Control variables at country level

Additionally, macro factors have a profound impact on local economic development. Therefore, we draw a set of country-level control variables to mitigate the endogeneity of the omitted variables. Moreover, we can only evaluate the above factors using country-level data, owing to the opaqueness of government information in ASEAN at the city level. The variable of human capital, Edu, is the proportion of people over 15-years-old receiving higher education (Barro & Lee, 2013). The variable Fix is the proportion of fixed-asset investment in the GDP. FDI is the proportion of foreign direct investment to GDP, representing the economic openness of the country. Gov is the proportion of government expenditure to GDP, indicating government intervention in the economy. Table 3 reports the variable explanation and data sources.

| Variables | Definition | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | LnDN | The natural log of the average DN value of each city indicates the subnational economic development. | https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/dmsp/downloadV4composites.html |

| Explanatory Variables (FriendshipCity) | City | An indicator variable equal to 1 if the city establishes a friendship-city relation with China in year t and after. | http://www.cifca.org.cn |

| In particular, when the friendship-city relation is established between provinces, City is defined as 1 for the provincial capital city, and 0 otherwise. | |||

| In this case, the definition focus on capital-city-level interaction. | |||

| Prov | The same indicator variable setting as City. | http://www.cifca.org.cn | |

| Note that Prov is defined as 1 for all the cities in the same provinces, and 0 otherwise when the friendship-city relation is established between provinces. | |||

| This definition tests the global effect on all of the cities' economic development within the same “friendship province.” | |||

| Control variables at the city level | Lnarea | The natural log of city land area (square km). | https://gadm.org/download_country_v3.html |

| Lnalt | The natural log of city average altitude (km). | http://www.worldclim.org/ | |

| Suit | Suitability index for agriculture based on temperature and soil quality measurements. | http://nelson.wisc.edu/sage/data-and-models/atlas/maps.php?datasetid=19&includerelatedlinks=1&dataset=19 | |

| Lndist | The natural log of the distance between the city center and the nearest coastline (km). | https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/shorelines/gshhs.html | |

| Petro | An indicator variable is equal to 1 if there is petrol or gas in the city, 0 otherwise. | https://www.prio.org/data/11 | |

| Lnpop | The natural log of the city population. | LandScan data set | |

| https://landscan.ornl.gov/ | |||

| Mono | Spatial demographic agglomeration degree of ASEAN provincial capital city, calculated based on the population of CBD 3 km buffer divided by the provincial population. | Calculated by authors following Liu et al. (2017) | |

| Control variables at the country level | Edu | The proportion of people over 15-years-old receiving higher education represents the human capital. | Barro and Lee (2013) |

| http://www.barrolee.com/ | |||

| Fdi | Foreign direct investment scaled by GDP represents economic openness. | EIU national data set | |

| Fix | Fixed asset investment scaled by GDP represents the capital investment. | EIU national data set | |

| Gov | Government expenditure scaled by GDP represents the government intervention. | EIU national data set |

- Abbreviations: ASEAN, Association of Southeast Asian Nations; CBD, central business district; DN, digital number; GDP, gross domestic product.

3.6 Estimation model

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

4.1 Descriptive statistics

We obtain a balanced panel data set during the period from 2000 to 2013 by excluding samples with missing variables, and we winsorize continuous control variables at the 1% and 99% percentiles. Table 4 provides the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The mean value of City is 0.012, indicating that 1.2% of the cities belong to the treatment group when only provincial capital cities are labeled as treatment cities. The mean value of Prov is 11.1%, indicating that 11.1% of the cities belong to the treatment group if all cities in the two provinces are labeled as treatment cities. Additionally, the suitability for agriculture index is 0.495 on average, and approximately 11% of the cities in ASEAN have oil or natural gas resources, indicating a good natural endowment of agriculture and energy resources. Regarding country-level control variables, the proportion of people receiving higher education in the sample is 0.151, the city level of economic openness is 0.027, and the proportions of fixed asset investment and government expenditure are 0.242 and 0.101, respectively. Overall, the macro-level control variables used in this study are consistent with the economic development of ASEAN countries.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnDN | 0.633 | 1.920 | −8.023 | 5.017 | 51,254 |

| City | 0.012 | 0.110 | 0 | 1 | 51,254 |

| Prov | 0.111 | 0.314 | 0 | 1 | 51,254 |

| Lnarea | 6.086 | 1.484 | 0.874 | 11.41 | 51,254 |

| Lnalt | 4.560 | 1.599 | −1.843 | 7.831 | 51,254 |

| Suit | 0.495 | 0.290 | 0 | 0.998 | 51,254 |

| Lndist | 3.657 | 1.335 | −1.287 | 6.699 | 51,254 |

| Petro | 0.110 | 0.314 | 0 | 1 | 51,254 |

| Lnpop | 5.067 | 1.450 | −0.497 | 10.65 | 51,254 |

| Mono | 0.161 | 0.194 | 0 | 1 | 51,254 |

| Edu | 0.151 | 0.117 | 0 | 0.668 | 51,254 |

| Fdi | 0.027 | 0.022 | −0.025 | 0.143 | 51,254 |

| Fix | 0.242 | 0.047 | 0.098 | 0.351 | 51,254 |

| Gov | 0.101 | 0.031 | 0.034 | 0.171 | 51,254 |

4.2 DID results

Table 3 shows the baseline DID regression results. There may be an inverse causal relationship between the city and national control variables and city economic development. Adding endogenous control variables to the regression equation may result in a "bad control" problem (Angrist & Pischke, 2009). Therefore, the estimates have a large error without accuracy. Therefore, we do not introduce any control variables in columns (1) and (4) of Table 5. As shown, the establishment of China–ASEAN friendship-city relation significantly promotes the economic growth of ASEAN friendship cities, regardless of whether control variables are added. The coefficients of City and Prov are significantly positive at the 1% level. Columns (1)–(3) show that the friendship-city relationship significantly boosts the regional economic development of ASEAN countries. Note that the results in columns (4)–(6) demonstrate that the friendship-city relationship also significantly benefits the economic development of second administrative cities within the first-level administrative division; that is, all cities in the friendship-province can enjoy economic benefit from the friendship-city relationship. Therefore, the economic effects of friendship-city relationships are profound and extensive.

| Explanatory variables | Dependent variable = LnDN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| City | 2.445 (0.151)*** | 0.670 (0.080)*** | 0.662 (0.080)*** | |||

| Prov | 0.694 (0.073)*** | 0.128 (0.035)*** | 0.122 (0.035)*** | |||

| Lnarea | −0.173 (0.024)*** | −0.174 (0.024)*** | −0.164 (0.024)*** | −0.164 (0.024)*** | ||

| Lnalt | −0.033 (0.013)** | −0.032 (0.013)** | −0.034 (0.013)** | −0.034 (0.013)** | ||

| Suit | 0.541 (0.070)*** | 0.537 (0.070)*** | 0.518 (0.070)*** | 0.516 (0.070)*** | ||

| Lndist | −0.170 (0.018)*** | −0.170 (0.018)*** | −0.168 (0.017)*** | −0.168 (0.017)*** | ||

| Petro | 0.371 (0.052)*** | 0.368 (0.052)*** | 0.363 (0.052)*** | 0.362 (0.051)*** | ||

| Lnpop | 0.878 (0.021)*** | 0.878 (0.021)*** | 0.889 (0.021)*** | 0.889 (0.021)*** | ||

| Mono | −0.390 (0.053)*** | −0.425 (0.071)*** | −0.384 (0.053)*** | −0.410 (0.071)*** | ||

| Edu | 0.043 (0.020)** | 0.034 (0.020)** | ||||

| Fdi | 0.040 (0.004)*** | 0.041 (0.004)*** | ||||

| Fix | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | ||||

| Gov | −0.008 (0.005) | −0.008 (0.005) | ||||

| Constant | −1.221 (0.248)*** | −2.293 (0.345)*** | −3.694 (0.297)*** | −1.686 (0.246)*** | −2.399 (0.346)*** | −3.783 (0.298)*** |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.147 | 0.711 | 0.712 | 0.139 | 0.710 | 0.711 |

| Observation | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 |

- Note: Robust standard errors are clustered by city and reported in parentheses. The coefficients of the fixed effects for year and country are suppressed for brevity.

- Abbreviations: DID, difference-in-difference; DN, digital number.

- *, ** and ***Statistical significance at the p < 0.10, p < 0.05, and p < 0.01 levels, respectively.

Regarding the control variables, the natural resource endowment of each city plays an important role in economic development. The regression coefficients of the suitability index for agriculture (Suit), petrol and gas resources (Petro), and city population (Lnpop) are significantly positive, indicating that the city's economic growth is higher with better agricultural resources, richer natural resources, and a larger population. The land area of cities (Lnarea), average altitude (Lnalt), distance to the coastline (Lndest), and city spatial agglomeration degree (Mono) are significantly negative. Note that a negative Mono means a more monocentric spatial structure of the provincial capital city causes a crowding-out effect on the economic development of other cities in the same province, which is consistent with the spatial explanations of Liu et al. (2017). Additionally, the economic openness of ASEAN economies (Fdi) and human capital (Edu) have a significant positive impact on city economic growth, which is consistent with existing literature. However, the estimates of physical capital (Fix) and government expenditure (Gov) are not significant. This may be attributed to the fact that the economic power of national investment and government intervention of ASEAN countries cannot be transmitted to the city through an effective channel.

4.3 PSM–DID results

Although the baseline results of DID estimation support that the friendship-city relationship is significantly related to subnational economic growth, there may be concerns of sample self-selection bias due to the limitations of data. Therefore, we construct a counterfactual framework of PSM–DID to alleviate the estimation error caused by inherent selection bias.

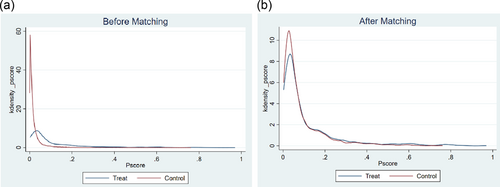

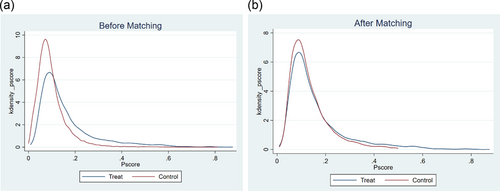

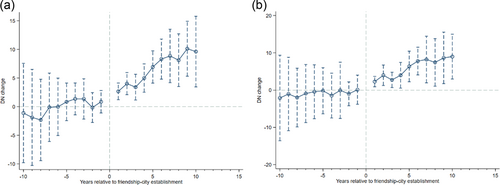

We test the precondition of parallel trend using the sample used in the benchmark regression and PSM sample to rule out the endogeneity concern of time-varying DID. The parallel trend tests are reported in Figure A1. In this section, we use the PSM–DID method to verify the robustness of the baseline results to overcome the systematic disparity between friendship cities and other cities. In the PSM–DID process, we conduct a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching for each year based on City and Prov. Figures 4 and 5 show the matching results plotted by the kernel density curve of the propensity score values between the treatment and control groups. The blue line indicates the treatment sample that has established city diplomatic relations with China, whereas the red line refers to the control sample. The kernel density lines of propensity scores in the treatment and control groups became closer after PSM matching, indicating a reliable matching result and a reasonable selection of characteristic variables.

Further, we used the matched data to conduct the DID estimation. Table 6 reports the PSM–DID regression results. The PSM–DID results are consistent with the baseline DID estimation. The coefficients of City and Prov in all regressions in Table 6 are significantly positive at the 1% level, whereas the magnitude of coefficients decreases compared with Table 5. This result shows that the conclusion using PSM–DID remains unchanged. In other words, the economic development of China–ASEAN cities after the establishment of friendship-city relations is greater than that of non-friendship-city relations. In summary, the DID and PSM–DID results verify hypothesis H1.

| Explanatory variables | Dependent variable = LnDN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| City | 0.797 (0.012)*** | 0.541 (0.008)*** | 0.556 (0.008)*** | |||

| Prov | 0.230 (0.004)*** | 0.166 (0.021)*** | 0.176 (0.022)*** | |||

| Constant | −0.573 (0.222) | −5.905 (0.426)*** | −7.476 (0.863)*** | −1.051 (0.163)*** | −3.185 (0.421)*** | −3.725 (0.437)*** |

| Controls at the city level | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Controls at the country level | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.297 | 0.819 | 0.822 | 0.065 | 0.726 | 0.727 |

| Observation | 882 | 882 | 882 | 8410 | 8410 | 8410 |

- Note: Robust standard errors are clustered by city and reported in parentheses. For brevity, the coefficients of the control variables and fixed effects for year and country are suppressed.

- Abbreviations: DN, digital number; PSM–DID, propensity score matching–difference-in-difference.

- *, **, and ***Statistical significance at the p < 0.10; p < 0.05; p < 0.01 levels, respectively.

4.4 Endogeneity discussion: Placebo test

First, it is a permanent challenge to exclude the endogeneity of empirical analysis. Besides, there are also not enough detailed city-level statistics to control the sample self-selection bias in this study. To address such endogeneity concerns, we first try to control city-level characteristics as much as possible in a city fixed effect model. Second, we adopt several methods of causal inference, including DID with a parallel trend test, PSM–DID, and placebo tests to alleviate self-selection bias. In particular, the parallel trend test provides important evidence, indicating that even though the choice of a city to establish the friendship-city relationship is not random, the pre-establishment economic performance of friendship cities and non-friendship cities does not present a significant difference. Moreover, the setting of DID is a powerful model that can provide a relatively clean estimation and allows us to look at the effect of policy intervention. In the above section, we further use PSM to balance the unobserved disparity between treatment and control groups to reduce self-selection bias. The coefficient of City/Prov in baseline DID is 0.662 (0.122). While in terms of PSM–DID estimation, the coefficient is 0.556 (0.176) in PSM–DID. The coefficients of DID model and the PSM–DID model are similarly and significantly positive, indicating that the results remain robust in the above quasi-experiment settings.

To further validate the robustness of baseline results, we propose a placebo design to testify whether the results are driven by other unobserved factors. The original core variable of baseline results, City/Prov, denotes the years of friendship city establishment and afterward. Our placebo method is to construct a “pseudoestablishment year” based on the real establishment year of friendship-city relations.

The sample of friendship cities is divided into two subgroups taking the year 2007 as the establishment boundary. First, for the friendship cities that establish the friendship-city relation before 2007 (including 2007), the pseudoestablishment year would be set as a postestablishment year. We define a dummy variable City_Placebo (Prov_Placebo), which equals 1 for the real establishment year postponed for 2 or 3 years. Second, for the other friendship cities with establishment year after 2007, the pseudoestablishment year would be set in advance. In this case, the placebo variable City_Placebo (Prov_Placebo) equals 1 for the pre-establishment year that is advancing the real establishment year for 2 or 3 years. If the coefficients of the placebo variable are not significantly positive, then it means that the pseudo friendship-city relations do not bring positive influence, and the causal inference of the friendship-cities relationship on subnational economic development in the baseline regression is supported.

Table 7 reports the placebo test results. Placebo test results of pseudo-establishment on the scale of 2 years are shown in columns (1) and (3), and columns (2) and (4) represent pseudo-establishment on the scale of 3 years. All of the coefficients of the placebo variables (City_Placebo/Prov_Placebo) are insignificantly positive, indicating that pseudo friendship-city relationships do not have a significant impact on local economic development. This shows that the significant positive effect on subnational economic growth in the baseline DID model is driven by the friendship-city relationship establishment, instead of other policy shocks.

| Explanatory variables | Dependent variable = LnDN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 2 years | 3 years | 2 years | 3 years | |

| City_Placebo | 0.125 (0.104) | 0.140 (0.102) | ||

| Prov_Placebo | 0.076 (0.069) | 0.077 (0.067) | ||

| Constant | −2.328 (0.349)*** | −2.330 (0.328)*** | −2.336 (0.343)*** | −2.336 (0.348)*** |

| Controls at the city level | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls at the country level | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.725 | 0.736 | 0.736 | 0.736 |

| Observation | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 |

- Note: Robust standard errors are clustered by city and reported in parentheses. For brevity, the coefficients of the control variables and fixed effects for year and country are suppressed.

- Abbreviation: DN, digital number.

- *, **, and ***Statistical significance at the p < 0.10, pp < 0.05, and p < 0.01 levels, respectively.

5 TESTS OF UNDERLYING CHANNELS

5.1 Channel of bilateral trade

In recent years, international trade between China and ASEAN countries has developed rapidly. Since the establishment of the ASEAN–China free trade zone in 2010, the free trade zone has not only boosted China–ASEAN trade but has also prompted ASEAN to become China's second-largest trade partner in 2019.10 Meanwhile, according to the China–ASEAN Business Council, China's trade with ASEAN has reached 85.32 billion USD, and ASEAN has historically become China's largest trading partner in 2020.11 This trade connection remains strong even after the impeded trade and business shutdown caused by the global pandemic, which shows that trade exchanges have become a driving force for China–ASEAN regional economic development. The establishment of friendship-city relationships can reduce the distance between people from different backgrounds and enhance economic and trade exchanges. Therefore, trade exchanges between China and ASEAN countries could be an underlying channel of the economic development of ASEAN cities.

First, since trade data for ASEAN cities are not available, this study evaluates the trade intensity between ASEAN cities and China at the national level. We define the median value of total bilateral trade volume, including import and export between ASEAN and China as the threshold to construct a dummy variable Trade. Trade equals 1 if the proportion of trade volume between the ASEAN country and China is greater than the median and 0 otherwise. We identify the influence of bilateral trade intensity on the relationship between friendship-city relationship and subnational economic development by adding the interaction term FriendshipCity*Trade into the benchmark model. Table 8 presents the test results for the trade channel. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8 present the estimates after considering the intensity of bilateral trade. Consistent with our initial findings, the coefficients of City and Prov are positive and significant (p < 0.01) in the DID model. A positive coefficient suggests greater economic development for the treatment cities in the post-period. Moreover, as predicted, the interaction term between FriendshipCity and trade is positive and significant (p < 0.1), suggesting that the association between friendship city and economic development is stronger in treatment cities after the establishment of friendship city. This shows that when bilateral trade between ASEAN countries and China is closer, the impact on the economic development of the friendship-city relationship is more significant.

| Explanatory variables | Dependent variable = LnDN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral trade | Direct investment | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| City | 0.639 (0.080)*** | 0.837 (0.091)*** | 0.582 (0.087)*** | |||

| Prov | 0.104 (0.035)*** | 0.359 (0.031)*** | 0.132 (0.038)*** | |||

| FriendshipCity × Trade | 0.582* (0.012) | 0.561 (0.194)*** | ||||

| Trade | −0.277 (0.034)*** | −0.311 (0.037)*** | ||||

| FriendshipCity× lnDistB | −0.379 (0.010)*** | −0.457 (0.041)*** | ||||

| lnDistB | 0.045 (0.117) | 0.069 (0.018)** | ||||

| FriendshipCity × Project | 0.250 (0.109)** | −0.067 (0.067) | ||||

| Project | 0.013 (0.018) | 0.026 (0.060) | ||||

| Constant | −1.937 (0.356)*** | −5.905 (0.426)*** | −2.499 (0.024)*** | −3.424 (0.360)*** | −2.404 (0.358)*** | −2.404 (0.358)*** |

| Controls at the city level | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls at the country level | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.713 | 0.712 | 0.713 | 0.713 | 0.713 | 0.712 |

| Observation | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 |

- Note: Robust standard errors are clustered by city and reported in parentheses. For brevity, the coefficients of the control variables and fixed effects for year and country are suppressed. Variable FriendshipCity in columns (1), (3), and (5) represents the variable City, the treatment of the provincial capital city when the friendship-city relationship is established in the province, while FriendshipCity in (2), (4), and (6) represents the variable Prov, treatment of all cities within a province when the friendship-city relationship is established in the province.

- *, **, and *** Statistical significance at the p < 0.10, p < 0.05, p < 0.01 levels, respectively.

Second, we include the spherical distance between China's border and the city centroid of ASEAN countries to capture the trade costs with China. Specifically, we add the natural logarithm of the spherical distance lnDistB calculated using ArcGIS to the baseline specification (6). The estimates are shown in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 8. The coefficients of the interaction term FriendshipCity × lnDistB are significantly negative (p < 0.01), suggesting that increased geographical distance from China induces greater trade costs for friendship cities and diminishes the impact of the friendship-city relationship on city economic development, which further validates the influential channel of bilateral trade on how a friendship-city relationship boosts subnational economic development.

5.2 Channel of direct investment

The proxy for direct investment is the amount of China's foreign contracted project, defined as the project. Specifically, Project equals 1 if the foreign contracted project completion amount between China and ASEAN countries is greater than the median and 0 otherwise. The interaction term FriendshipCity*Project is included in specification (6), and the estimates are presented in columns (5) and (6) of Table 8. As shown, the coefficient of the interaction item FriendshipCity*Project in column (6) shows that China's investment in ASEAN countries has no significant effect on the economic promotion of all cities in the provinces that have friendship-city relations. Whereas, the coefficient of the interaction item FriendshipCity*Project in column (5) direct investment of contracted projects has a significant effect (p < 0.05) on the friendship cities and friendship-province represented by sole provincial capital cities, indicating that foreign direct investment may also be an effective channel for only provincial capital cities. In other words, China's direct investment in the contracted project is an effective channel for a friendship-city relationship, but the effect is limited within provincial capital cities.

In sum, the channel test results of trade and direct investment support the influential channels proposed by hypothesis H2.

5.3 Channel of mutual visits by national leaders

Following Nitsch (2007), we use the number of national leaders' state visits12 between China and ASEAN to construct a set of dummies to capture different aspects of the leaders' state visits, by adding interaction terms into the specification (6). We define the following variables: (1) Visit1 equals the total number of visits to ASEAN countries by China's leaders, including the President, Prime Minister, and other senior officials; (2) Visit2 equals the total number of visits to China by foreign leaders, including the president, prime minister, and other senior officials of an ASEAN country; (3) Visit3 equals the total number of visits to ASEAN countries by China's president and prime minister; (4) Visit4 equals the total number of visits to ASEAN countries by China's other senior officials at or above the ministerial level. In this section, we report the results of the variable City as an example in Table 9.

| Explanatory variables | Dependent variable = LnDN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| City | 0.654 (0.107)*** | 0.555 (0.148)*** | 0.600 (0.111)*** | 0.630 (0.120)*** |

| visit1 | 0.012 (0.001)*** | |||

| City × visit1 | 0.005 (0.002)* | |||

| visit2 | 0.001 (0.002) | |||

| City× visit2 | 0.030 (0.026) | |||

| visit3 | 0.003 (0.001)** | |||

| City × visit3 | 0.028 (0.012)** | |||

| visit4 | 0.010 (0.002)** | |||

| City × visit4 | 0.010 (0.005)* | |||

| Constant | −2.152 (0.264)*** | −2.071 (0.262)*** | −2.082 (0.262)*** | −3.424 (0.360)*** |

| Controls at the city level | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls at the country level | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.710 | 0.712 | 0.712 | 0.714 |

| Observation | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 | 51,254 |

- Note: Robust standard errors are clustered by city and reported in parentheses. For brevity, the coefficients of the control variables and fixed effects for year and country are suppressed.

- *, **, and ***Statistical significance at the p < 0.10; p < 0.05; p < 0.01 levels, respectively.

First, columns (1) and (2) of Table 9 reflect the different effects of state visits by Chinese and foreign leaders, while columns (3) and (4) of Table 6 reflect the effects of visits by Chinese leaders from different official levels. As shown in column (1), the coefficient of Visit1 is significantly positive (p < 0.01), suggesting that Chinese leaders' state visits to ASEAN countries can promote the economic development of all friendship cities. The coefficient of the interaction term City*Visit1 is significantly positive (p < 0.1), but the magnitude is relatively small (0.005). This indicates that the economic promotion effect of leaders' state visits to friendship cities is greater than that of non-friendship cities and, in particular, the visits of Chinese leaders can enhance the association between friendship-city relations and the economic development of China–ASEAN friendship cities. In contrast, column (2) shows that the coefficients of Visit2 and City × Visit2 are insignificant, indicating that ASEAN leaders' visits to China do not have significant economic effects on ASEAN friendship cities. Furthermore, columns (3) and (4) in Table 9 show the comparison of the effects of state visits by Chinese leaders and senior officials or above ministers. The City × Visit3 coefficient of column (3) is 0.028 and significant (p < 0.05); the City× Visit4 coefficient of column (4) is 0.010 (p < 0.10). Therefore, the visits of China's top-level leaders to ASEAN countries have a greater economic magnitude than those of officials at the ministerial level. The results show that the exchange form of state visits of high-level national leaders is a possible channel that affects the relationship between friendship-city relations and subnational economic development. Therefore, the channel of mutual visits by national leaders proposed by hypothesis H2 is verified.

6 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Motivated by the questions of whether and to what extent the friendship-city relationship affects a city's economic development in developing economies, we document a data set of China–ASEAN friendship cities by collecting multiple city-level data. We collect paring data of friendship cities, subnational economic indicators from nighttime light data sets, and ASEAN city-level characteristics that include natural resource endowment and geographical features. Based on the empirical analysis of DID, PSM–DID models, and placebo test, we find that connecting people in the form of the friendship-city relationship between 2000 and 2013 is a key impetus for regional economic performance that has boosted the subnational economic development of China–ASEAN friendship cities. Further tests show that bilateral trade, China's investment in contracted projects, and state visits by national leaders may be the underlying channels. We contribute to prior literature by providing empirical evidence on whether and how friendship city establishment influences subnational economic development and shed light on the economic effect of city diplomatic interaction and the potential of connecting people to pave the Belt and Road forward.

The main implications of this study are as follows. First, the global cooperation strategy of the BRI led by China could reach an all-win benefit with mutual cooperation through profound city-to-city ties. Despite various challenges posed by the initiative to their national strategies, countries along the BRI have the potential to improve their economic conditions by exploring complementarities through in-depth multiple-level people-to-people exchanges, trade, and China's contracted infrastructure in the platform of the friendship-city relationship. The construction of the friendship-city relationship has shed light on developing five dimensions of connectivity proposed by the BRI, and friendship-city relations should be prioritized during the process of developing people-to-people connectivity between different countries and the world.

International cooperation is the core of regional development built on the pillars of mutual trust. In particular city-to-city ties in the form of friendship-city relationships enhance mutual understanding through intensifying people-to-people connectivity, building friendship, and deepening mutual trust. With greater mutual trust, the subnational close cooperation in economic activities, trade, exchange of culture, and so forth, is able to thrive in a stable circumstance. Moreover, countries along the BRI with a mutual-trust network of friendship cities should take advantage of international trade and infrastructure construction and enhance the interconnection and cooperation channels. For instance, with China's strengths in infrastructure and manufacturing and Vietnam's advantages in industrial labor, the two countries have much unique capacity to offer to each other and draw upon each other's strong points.

From the perspective of developing the friendship-city network, it is important not only to encourage Chinese enterprises to go abroad but also to accentuate the Chinese city itself as a distinguishing landscape on the international stage. The establishment of the friendship-city network is not only conducive to promoting cultural exchanges and enhancing China's soft power but also is effective in promoting the globalization and diversified development of modern cities. For this reason, it is vital for China's local government to emphasize the friendship-city network by expanding subnational conversations and activities oriented toward trade and investment and other economic cooperation.

At last, the emergence of novel big data sources assists to extend subnational socioeconomic studies on a large spatial scale. However, we could not extend our study to a broader window since the latest DMSP/OLS nighttime light data set ended in 2013. Future studies could take advantage of the long time-series big data such as NPP-VIIRS to construct alternative proxies and investigate the effects of regional policy on a larger scale at finer administrative levels.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fangying Pang: Formal analysis; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review and editing. Jingjing Tang: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Writing – review and editing. Hanwen Xie: Data curation; Software.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the attendants and editors who participated in the Chinese Economist Society (CES) 2021 Annual Conference and the forum of the 5th China Trade Power for their constructive comments. The editors' and reviewers' constructive comments on the paper are also gratefully acknowledged. Any errors, opinions, and omissions are our own. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (No. 71764001) and Ministry of Education Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences (No. 17XJC790012).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None declared.

APPENDIX A:

1. Parallel trend examination

2. Estimated parameters of intersensor calibration model

| Satellites | Year | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F12 | 1998 | 1.8857 | 0.5692 | 0.7768 |

| 1999 | 1.3018 | 0.8469 | 0.8235 | |

| F14 | 2000 | 1.7623 | 0.6908 | 0.8971 |

| 2001 | 1.5192 | 0.7893 | 0.8837 | |

| 2002 | 1.2849 | 0.7133 | 0.8663 | |

| 2003 | 1.6747 | 0.7096 | 0.8726 | |

| F15 | 2000 | 1.9862 | 0.6594 | 0.8569 |

| 2001 | 1.8509 | 0.6811 | 0.8541 | |

| 2002 | 1.9294 | 0.7398 | 0.8712 | |

| 2003 | 1.3605 | 0.8599 | 0.8375 | |

| 2004 | 1.4109 | 0.8244 | 0.8764 | |

| 2005 | 1.0915 | 0.8203 | 0.8412 | |

| 2006 | 1.6094 | 0.8894 | 0.8637 | |

| 2007 | 1.7923 | 0.9821 | 0.8579 | |

| F16 | 2004 | 1.4766 | 0.8759 | 0.9233 |

| 2005 | 1.0843 | 0.8562 | 0.9129 | |

| 2006 | 1.3209 | 0.7821 | 0.9025 | |

| 2007 | 1.9506 | 0.8831 | 0.8351 | |

| 2008 | 1.5295 | 0.8965 | 0.8002 | |

| 2009 | 2.0836 | 0.7182 | 0.7983 | |

| F18 | 2010 | 1.9085 | 0.7859 | 0.8405 |

| 2011 | 1.8701 | 0.8984 | 0.8792 | |

| 2012 | 2.0134 | 0.7911 | 0.9091 | |

| 2013 | 2.1321 | 0.7208 | 0.8642 |

3. Illustration of DMSP-OLS nighttime images

To further verify the authenticity of using nighttime lights to capture subnational economic development in ASEAN countries, we provide two images based on the capital relocation event of Naypyidaw of Myanmar in 2005 in Figure A2. Figure A2 presents images of Naypyidaw before and after the capital relocation with zoom ratio of 1:338,000 based on the ArcGIS platform. It can be seen that after the capital relocation in 2006, the DN values have been significantly expanded and enhanced. It reflects that Myanmar's capital relocation has rapidly driven the socioeconomic development of Naypyidaw. The change of night light data is synchronized with the ASEAN subnational economic development.

4. Region category of BRI countries

| ASEAN | Southern Asia | East Asia | Central and Eastern Europe | Russia | West Asia and North Africa | Central Asia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaysia | Maldives | Mongolia | Serbia | Montenegro | Russia | Palestine | Azerbaijan | Uzbekistan |

| Singapore | Sri Lanka | South Korea | Bulgaria | Moldova | Georgia | Iran | Tajikistan | |

| Indonesia | Bengal | North Korea | Romania | Republic of Macedonia | Egypt | Armenia | Kazakhstan | |

| Brunei Darussalam | Pakistan | Croatia | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Israel | Iraq | Kyrgyzstan | ||

| Philippines | India | Slovakia | Latvia | Jordan | Saudi Arabia | Turkmenistan | ||

| Thailand | Afghanistan | Hungary | The Czech Republic | Syria | Bahrain | |||

| Cambodia | Nepal | Slovenia | Ukraine | Turkey | Yemen | |||

| Laos | Timor-Leste | Albania | Belarus | Lebanon | The United Arab Emirates | |||

| Vietnam | Bhutan | Estonia | Kuwait | |||||

| Myanmar | Lithuania | Oman | ||||||

| Poland | Qatar | |||||||

- Source: CSMAR–The Belt and Road research database.

REFERENCES

- 1 Available at http://www.china.org.cn/english/china_key_words/2019-04/17/content_74691589.htm.

- 2 Available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/.

- 3 For example, the Belt and Road Big Data Report 2018 is available at http://www.sic.gov.cn/News/614/9766.htm.

- 4 The sample countries include Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos. We excluded Singapore and Brunei from our sample because there is no comparable control group for these two countries as Singapore is regarded as a megacity economy, and Brunei is a small country with a 5765 km2 territory and a population of less than 450,000 in 2018.

- 5 General Statistics Office of Vietnam, https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/national-accounts/publication/. Note that the only subnational statistics we can find started from 2015 to 2018 and the source is at https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2020/05/socio-economic-statistical-data-of-63-provinces-and-cities/.

- 6 Available at http://wb.beijing.gov.cn/home/yhcs/sjyhcs/sj_yz/sj_yz_yjds/sj_yz_yjds_csgk/201912/t20191231_1547112.html.

- 7 Available at http://wb.beijing.gov.cn/home/yhcs/qjyhcs/zxdt/202111/t20211109_2532905.html.

- 8 Cao et al. (2015) provide similar results at China's mainland level, and the R2 value maintains larger than 0.83 in the power model.

- 9 The file's name is F16_20051128-20061224_rad_v4, available at https://ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/dmsp/download_radcal.html.

- 10 https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201911/02/WS5dbcd83ba310cf3e3557501d.html

- 11 http://www.china-aseanbusiness.org.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=81&id=33468

- 12 The data of national leaders’ mutual visits are collected from China Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.