DNA methylation biomarkers for noninvasive detection of triple-negative breast cancer using liquid biopsy

Funding information: Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum; German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg

Abstract

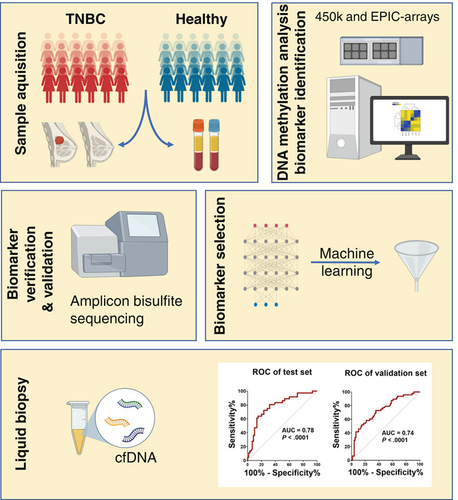

Noninvasive detection of aberrant DNA methylation could provide invaluable biomarkers for earlier detection of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) which could help clinicians with easier and more efficient treatment options. We evaluated genome-wide DNA methylation data derived from TNBC and normal breast tissues, peripheral blood of TNBC cases and controls and reference samples of sorted blood and mammary cells. Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between TNBC and normal breast tissues were stringently selected, verified and externally validated. A machine-learning algorithm was applied to select the top DMRs, which then were evaluated on plasma-derived circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) samples of TNBC patients and healthy controls. We identified 23 DMRs accounting for the methylation profile of blood cells and reference mammary cells and then selected six top DMRs for cfDNA analysis. We quantified un-/methylated copies of these DMRs by droplet digital PCR analysis in a plasma test set from TNBC patients and healthy controls and confirmed our findings obtained on tissues. Differential cfDNA methylation was confirmed in an independent validation set of plasma samples. A methylation score combining signatures of the top three DMRs overlapping with the SPAG6, LINC10606 and TBCD/ZNF750 genes had the best capability to discriminate TNBC patients from controls (AUC = 0.78 in the test set and AUC = 0.74 in validation set). Our findings demonstrate the usefulness of cfDNA-based methylation signatures as noninvasive liquid biopsy markers for the diagnosis of TNBC.

Graphical Abstract

What's new?

While early diagnosis of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is associated with heightened responsiveness to chemotherapy, biomarkers that can be detected noninvasively are needed to support early TNBC diagnosis. Our study suggests that such markers may exist in the form of methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Evaluation of methylation data from breast tissue and peripheral blood and plasma samples from TNBC patients and controls revealed the existence of aberrant methylation within 23 genomic regions in TNBC cases. Three differentially methylated regions exhibited marked differences in cell-free DNA levels between cases and controls, highlighting their potential as noninvasive markers for TNBC detection.

Abbreviations

-

- AUC

-

- area under the curve

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- cfDNA

-

- circulating cell-free DNA

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- ddPCR

-

- droplet digital PCR

-

- DMR

-

- differentially methylated region

-

- ER

-

- estrogen receptor

-

- HER2

-

- epidermal growth factor receptor 2

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- OS

-

- overall survival

-

- PCA

-

- principal component analysis

-

- PR

-

- progesterone receptor

-

- RFS

-

- recurrence-free survival

-

- ROC

-

- receiver operating characteristic

-

- TNBC

-

- triple negative breast cancer

1 INTRODUCTION

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive breast cancer (BC) subtype. It is characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression and accounts for 15% to 20% of all invasive BC cases in the Caucasian population. TNBC occurs most frequently in young or premenopausal women and African Americans.1 In addition, TNBCs are typically of higher histologic grade and are associated with a more advanced disease stage and poorer survival compared to other subtypes.2 The absence of the three hormone receptors presents a treatment challenge for targeted therapy and therefore neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy remains the mainstay of systemic medical treatment for TNBC patients.2, 3 Given that early-stage TNBC patients respond better to neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy,4 early detection can then have a high impact on patients' survival by preventing development of metastases.

Liquid biopsies have potential applications for minimally-invasive and earlier cancer management than conventional approaches.5 They can be applied for screening, diagnosis and prognosis of disease, personalized treatment or even during and after treatment, enabling clinicians and patients to adapt therapy and monitor disease burden accordingly.6 The identification of molecular biomarkers to support noninvasive earlier detection and prognosis of TNBC is an urgent clinical need which may improve survival in these patients. So far, several molecular markers have been proposed as potential biomarkers for TNBC,7 however, sensitive and specific biomarkers are still missing. DNA methylation signatures in cell-free DNA have been shown to be sensitive and specific for early detection of multiple cancer types,8 and several previous studies have reported differentially methylated genes in TNBC tissues compared to normal breast tissue or other BC subtypes.9, 10

Here, we report on the identification of DNA methylation biomarkers for TNBC using methylome data of tumor tissues and their application as noninvasive markers on cfDNA. We identified, verified and validated 23 differentially methylated regions (DMRs). Finally, ranking of the DMRs using a machine learning algorithm and clinical validation in cfDNA samples demonstrated that our findings hold potential for noninvasive detection of TNBC.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study populations and samples

TNBC fresh-frozen tissues from 123 patients and plasma samples from 139 patients (60 patients provided both tumor tissue and plasma) participating in the Städtisches Klinikum Karlsruhe Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum Breast Cancer Study (SKKDKFZS) were selected.11 Information on known and potential risk factors and follow-up was collected for all study participants from medical records, pathology reports and/or questionnaires. Table S1 summarizes the main characteristics of the study participants including the established BC risk factors age at diagnosis, menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal), family history of breast/ovarian cancer (yes, no), body mass index (BMI) (<20, 20 to <25, 25 to <30, ≥30 kg/m2) and parity (yes, no). Table 1 shows the histopathological data of the TNBC patients including histology (ductal, lobular, ductolobular, medullary, other), histological grade (G1, G2, G3), tumor size (in situ, T1, T2, T3, T4), lymph node status (N0, ≥N1), metastatic status (M0, M1), stage (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) and follow-up data (number of recurrences, number of deaths; median durations of follow-up and recurrence-free time [years]).

| Tumor tissue cohorta (n = 123) | Plasma cohorta (n = 139) | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Histology | ||

| Ductal | 94 (76) | 86 (62) |

| Lobular | 10 (8) | 17 (12) |

| Ductolobular | 8 (7) | 12 (8.6) |

| Medullary | 6 (5) | 10 (7.2) |

| Other | 5 (4) | 14 (10) |

| Histological grade | ||

| G1 | 2 (2) | 6 (4.3) |

| G2 | 50 (41) | 64 (46) |

| G3 | 71 (58) | 69 (49.6) |

| Tumor size | ||

| In situ | 1 (1) | 1 (0.7) |

| T1 | 32 (26) | 68 (49) |

| T2 | 84 (68) | 62 (44.6) |

| T3 | 6 (5) | 2 (1.4) |

| T4 | 0 (0) | 6 (4.3) |

| Lymph node status | ||

| N0 | 56 (46) | 85 (61) |

| ≥N1 | 65 (53) | 53 (38) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Metastatic status | ||

| M0 | 115 (93) | 134 (96.4) |

| M1 | 6 (5) | 5 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Stage | ||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (0.7) |

| 1 | 16 (13) | 42 (30.2) |

| 2 | 68 (55) | 69 (49.6) |

| 3 | 28 (23) | 18 (12.9) |

| 4 | 6 (5) | 5 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 4 (3) | 4 (2.9) |

| Follow-up | ||

| Recurrences | 37 (30) | 23 |

| Deaths | 35 (28) | 33 |

| Median follow-up (years) | ||

| Overall survival | 6.5 | 7 |

| Recurrence-free survival | 2.1 | 2.7 |

- a Tumor tissue and plasma from 202 TNBC patients were included in the two sample cohorts. There is an overlap of 60 patients (who provided both tumor tissue and plasma) between the two cohorts.

DNA was isolated from 123 fresh-frozen tumor samples of TNBC cases. After quality control, the DNA samples were applied to down-stream DNA methylation analysis. The plasma samples were derived from 139 TNBC patients and 84 healthy controls. Of the TNBC plasma cohort, 60 patients provided both tumor and plasma (test set) and 79 patients provided plasma only (validation set). To independently confirm our data from the tumor-informed approach, we analyzed the plasma samples of the two sample sets separately.

Blood samples from healthy individuals were collected by the German Red Cross Blood Service of Baden-Württemberg-Hessen (Mannheim, Germany) from September to December 2019 for plasma isolation. All blood donors were females aged 30 to 55 years at the time of blood donation. Details on the study populations can be found in Methods S1.

2.2 Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling

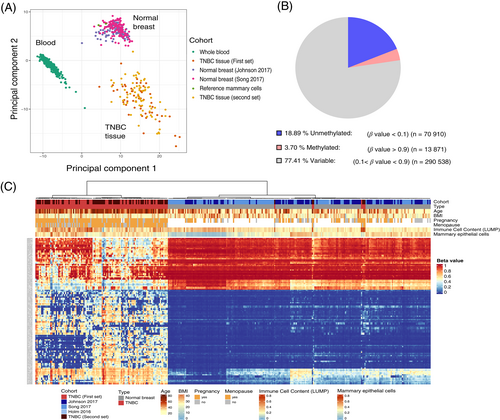

DNA methylation profiling of 123 TNBC tissues was performed at the DKFZ Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility (Heidelberg, Germany) using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip (n = 52) and the EPIC array (n = 71) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To account for cell type heterogeneity, we used the Houseman algorithm for reference-based deconvolution using DNA methylation data from sorted cell types. Estimated proportions of various mammary cells (fibroblasts, epithelial and endothelial cells), adipocytes and immune cells (using the LUMP: leukocytes unmethylation for purity algorithm) were used as covariates to account for cell type heterogeneity in bulk tumor methylation data.12, 13

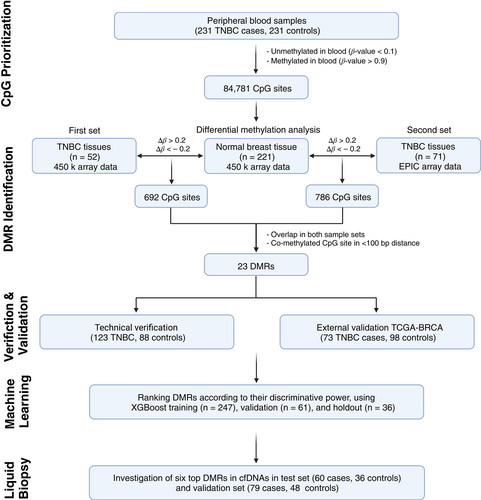

Additionally, to minimize the false positive detection and to increase the signal-to-noise ratio in cfDNA analysis, we selected CpG sites that were almost completely methylated (β-value >0.9) or unmethylated (β-value <0.1) in peripheral blood DNA (Figure 1) using methylation data from our previous genome-wide methylation study on 231 TNBC cases and 231 controls.14

Next, to identify DMRs, we compared the methylation level at the prioritized CpG sites (n = 84 781) between the two sets of TNBC tissues (first set: n = 52, second set: n = 71) and normal breast tissues (n = 221) (Figure 1). The methylation datasets under evaluation are provided in Table 2.

| Sample type | N | Platform/dataset |

|---|---|---|

| Whole blood (TNBC) | 231 | 450 k (in-house) |

| Whole blood (healthy) | 231 | 450 k (in-house) |

| Solid tissue (TNBC) | 123 | 450 k and EPIC (in-house) |

| Solid tissue (normal breast) | 221 | 450 k (GEOa) |

| Solid tissue (TNBC) | 73 | 450 k (TCGA) |

| Solid tissue (normal breast) | 98 | 450 k (TCGA) |

| Reference cell types | 46 | 450 k (GEOb) |

- Abbreviations: GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

- a GSE101961 and GSE88883.

- b GSE122126, GSE35069 and GSE74877.

2.3 Verification and external validation of the identified DMRs

The identified DMRs were verified by amplicon bisulfite sequencing at single-molecule resolution. PCR primers were designed manually and also using the AmpliconDesign webserver to amplify candidate loci from bisulfite-converted DNA15 (Table S2). For an external validation, DNA methylation datasets of TNBC tissues (n = 73) and normal breast tissues (n = 98) from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA-BRCA) were applied. Details on the method can be found in Methods S1.

2.4 Selection of top classifier DMRs by machine learning

To select CpG sites with the most predictive power, an eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model was trained based on methylation levels of CpG sites overlapping with the selected DMRs. In this respect, the TNBC and normal breast tissue cohorts were split into training (n = 247; Healthy = 159; TNBC = 88), validation (n = 61; Healthy = 39; TNBC = 22) and holdout (n = 36; Healthy = 23; TNBC = 13) datasets. Model training and hyperparameter tuning was performed on the training cohort using a fivefold cross-validation approach with a grid-search algorithm using the R caret package. Details on the method can be found in Methods S1.

2.5 Isolation of circulating cell-free DNA and bisulfite conversion

Plasma samples of 139 TNBC patients (test set: n = 60, validation set: n = 79) and 84 healthy controls (test set: n = 36, validation set: n = 48) were kept at −80°C until use. For each sample, cfDNA was extracted from 2 mL of plasma using the QIAamp MinElute ccfDNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Bisulfite conversion was carried out on cfDNA samples using the manufacturer's protocol for low concentration DNA samples (EpiTect bisulfite kit; Qiagen).

2.6 MethyLight droplet digital PCR

For investigation of the top DMRs in circulating cfDNA, MethyLight droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) was performed as previously described by us.14 Specific TaqMan probe assays were designed and ddPCR was employed for sensitive detection of aberrant methylation at target DMRs in cfDNA samples. The TaqMan probe assays were designed to include multiple nearby CpG sites considering co-methylation pattern of those CpGs. The length of amplicons was kept as short as possible to maintain higher likelihood of detection. All steps including droplet generation, thermal cycling and droplet reading were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols (Bio-Rad). The list of primer and Taqman probe sequences is provided in Table S3.

2.7 Statistical analyses

The diagnostic performance of individual selected CpGs was assessed using logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC)/area under the curve (AUC) analysis. In TNBC cases, the association of CpG methylation levels with clinical and epidemiological factors (age, menopausal status, family history of breast/ovarian cancer, BMI, parity), histopathological tumor parameters (grade, size, lymph node status, metastatic status, stage) and overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) was assessed. OS was defined as the time between TNBC diagnosis and death or last follow-up, whichever occurred first. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the time between TNBC diagnosis and reappearance of disease (locoregional relapse, distant metastasis). Mann-Whitney test, Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test and Spearman's correlation coefficient were used to assess associations between methylation levels and clinical, epidemiological and histopathological parameters. The impact of methylation level on OS was analyzed in a Cox regression model. Kaplan-Meier estimates and log-rank test were derived for methylation levels at median cut-off. To account for established prognostic factors, a multivariable Cox regression model including age, tumor grade, stage, tumor size and node status was fitted. Individual P-values were adjusted for multiple testing using Holm correction to control the family-wise error rate. All analyses have been done using R 3.6 with add-on packages rms, survival and pROC.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient and sample characteristics and data sets analyzed

We analyzed genome-wide methylation data (Illumina 450 k and EPIC arrays) of a total of 852 DNA samples from peripheral blood of 231 TNBC patients and 231 controls, 123 TNBC and 221 normal breast tissues and 46 reference cell including neutrophils, B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, monocytes, natural killer cells and various mammary cells (Table 2, Figure 1). Principal component analysis (PCA) using methylome data showed a clear separation of the samples into different clusters (Figure 2A). The TNBC tissues formed a more dispersed cluster that may be due to tumor heterogeneity and different ratios of tumor to nontumor cells in each sample. Clinical, epidemiological and histopathological characteristics of the TNBC patients and their tumors as well as follow-up data are provided in Tables S1 and 1, respectively. In summary, family history of breast/ovarian cancer was reported by 11% of patients. Ductal invasive carcinoma was the most common histological type, followed by lobular carcinoma. The majority of patients who provided tumor tissue and/or plasma had nonmetastatic disease (93% and 96.4%, respectively) and only a few patients had metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and sampling. The mean and median ages at diagnosis of TNBC were 57.0 and 58.6 years, respectively. Median follow-up of TNBC patients was 6.5 years for OS and 2.1 years for RFS.

3.2 Identification, verification and validation of differentially methylated regions

The data analyses performed to identify the most promising DMRs are shown in Figure 1. Considering that PBLs are the main source of cfDNA in healthy individuals, we prioritized those CpG sites that were almost completely methylated (β-value >0.9) or unmethylated (β-value <0.1) in peripheral blood DNA (Figure 2B) using data from our previous study.14 Following differential analysis, 23 DMRs (18 hypermethylated, 5 hypomethylated) with 52 CpGs were identified. The heatmap of hierarchical clustering shows the TNBC tissues and the normal breast tissues grouped into two main clusters (Figure 2C). The probes with their genomic location; position relative to known genes and CpG islands, and methylation data at the 52 CpG sites are shown in Table S4. The identified DMRs yielded AUCs ranging from 0.739 to 0.987 for discrimination of TNBC from normal breast tissue. Methylation levels at all 52 CpG sites were associated with TNBC in unadjusted and age-adjusted conditional logistic regression analysis (all P < .001; Table S4).

Using amplicon bisulfite sequencing, all DMRs were verified. The coverage and quality statistics of the targeted bisulfite sequencing analysis are for each sample summarized in Table S5. The methylation status of all DMRs was consistent with the initial data from the Illumina methylation arrays. Representative results of the amplicon sequencing of the 23 DMRs in TNBC and normal breast tissues are shown in Figure S4.

For independent validation of the DMRs, we analyzed the available TCGA-BRCA data. Statistically significant methylation differences between the TNBC and normal breast tissues were found, with a P-value ≤.0001 for all available CpG sites and methylation differences in the range of 0.22 to 0.43, confirming our findings (Figure S2).

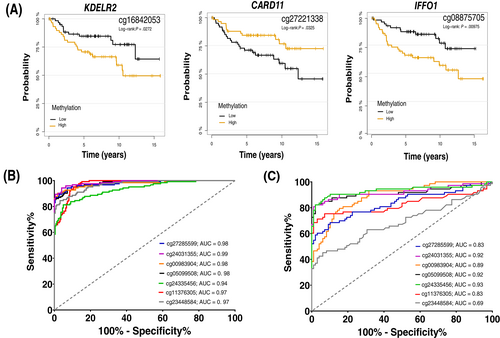

Aberrant DNA methylation could affect expression of the associated genes, which may have prognostic potential. In that respect and using the Kaplan-Meier (KM) plotter tool, we analyzed gene-expression data of several combined BC studies to see whether expression of genes associated with the DMRs predicts patient survival.16 Using the median to split gene expression level, expression levels of nine genes including CARD11, EPSTI1, IFFO1, KDELR2, MIAT, PPP1R16B, SLC7A4, TXNR and ZNF750 were associated with OS of BC patients (Figure S3). The methylation levels of three of these genes, CARD11, IFFO1 and KDELR2, were also associated with OS in our study cohort (Figure 3A).

3.3 Correlation of methylation levels with clinical, epidemiological and histopathological parameters

Next, we assessed, whether methylation levels of 52 CpG sites which are located in the 23 selected DMRs are associated with age, menopausal status, family history of breast/ovarian cancer, BMI, parity and histopathological tumor parameters including histological grade, tumor size, lymph node status, metastatic status and stage. Two statistically significant associations were detected in analysis adjusted for multiple testing. Methylation levels at six CpG sites in three DMRs corresponding to the PPP1R16B, SFRP5 and CPXM1 genes were associated with age at diagnosis (Spearman's rank correlation, Padj < .05) (Table S6). Patients with an early age at diagnosis had lower methylation levels than those with a late age. Further, methylation levels at 10 DMRs corresponding to the ALPL, PPP1R16B, FAM110B/IMPAD1, SFRP5, KIAA1949, PRDM16, CPXM1, TXNRD1, SPHK2 and PROCA1 genes were associated with tumor grade (Mann-Whitney test, Padj < .05) (Table S7). Methylation levels were significantly different in grade 3 tumors compared to grade 1/grade 2 tumors (Figure S4).

3.4 Prioritization of top classifiers for liquid biopsy applications

A machine learning algorithm was applied to select CpG sites within the DMRs that have the highest predictive power to discriminate TNBC patients from healthy controls. We, therefore, trained an XGBoost model based on the training cohort that predicted patients of the validation and holdout datasets independently with an accuracy of 100%. Subsequent feature selection based on the CpG sites with the highest model contribution, revealed 12 CpGs that accurately discriminate TNBC patients from healthy controls (Figure S5A,B). With respect to diagnostics, the AUC values of all selected top sites were close to one (range 0.94-0.99), demonstrating their high potential as biomarkers for TNBC diagnosis (Figure 3B). Somewhat lower AUC values (range 0.69-0.93) were calculated using TCGA-BRCA data (Figure 3C).

3.5 Sensitive detection of methylation markers from cfDNA

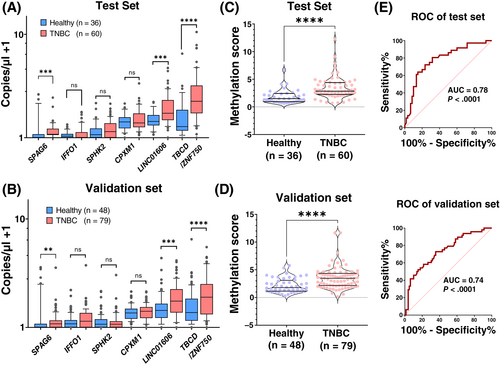

Due to the limitations within the amount of cfDNA for the analysis of all 12 CpGs, the top 7 CpGs (6 DMRs) from this selection were used to further analyze plasma-derived cfDNA samples from TNBC cases and controls. The six designed TaqMan assays were able to specifically detect the desired alleles in a bulk of background unmethylated/methylated DNA. Four assays were specific for the methylated allele and two for the unmethylated alleles. The copy numbers per microliter of each top six DMR candidates was measured on cfDNA samples from TNBC patients and healthy controls using methylation-specific ddPCR. Copy numbers at three DMRs (for the methylated allele of SPAG6, and for the unmethylated alleles of LINC10606 and TBCD/ZNF750) were significantly higher in TNBC patients compared to controls in both the test and the validation set (Figure 4A,B). The AUC values to discriminate TNBC cases from healthy controls were 0.68, 0.70 and 0.73 for the top three DMRs The sum of the copy numbers of the three significant DMRs was calculated and used as methylation score for each sample. The median methylation score was 2.14 for TNBC patients and 0.86 for healthy individuals. The difference in methylation scores between cases and controls in both sample sets was highly significant (P < .0001; Figure 4C,D). ROC analyses yielded AUC values of 0.78 on the test set and 0.74 on the validation set (Figure 4E,F). In addition, we also compared the methylation score in patients with different disease stages. Methylation scores in TNBC patients with late-stage disease (stages 3 and 4) were slightly higher compared to those with early-stage disease (stages 0 and 1 and stage 2), but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure S6).

4 DISCUSSION

Most cancer patients die because their cancers were not detected early enough to be cured by surgery or other available treatments. Minimally invasive early detection has significant potential to reduce the mortality of malignancies.5 Among all biological components which are shed from the tumor site into body fluids, ctDNA has been emerged as a rich source of genetic and epigenetic information.17 DNA methylation as stable epigenetic marks may occur early in carcinogenesis. Therefore, DNA methylation serves as an invaluable biomarker in oncology and molecular pathology for early cancer detection, noninvasive diagnosis, prognosis, treatment prediction and follow-up.18

In our study, we analyzed DNA methylation data of TNBC and normal breast tissues and, peripheral blood and plasma samples from TNBC cases and controls. Twenty-three methylation markers including novel ones with possible applications for molecular diagnosis/early detection of TNBC were identified, verified and validated. Since the methylation level from bulk tissue is a mixture derived from various cell types, methylation data were adjusted for cell type heterogeneity using the Houseman algorithm.19 Next, ranking of the DMRs by a machine learning approach and methylation analysis at six selected top DMRs in plasma-derived cfDNA samples of TNBC patients and controls confirmed the methylation differences, with three being statistically significant. Furthermore, a methylation score based on the selected top three DMRs was able to discriminate between TNBC cases and healthy controls.

The identified 23 DMRs overlapped with regulatory regions of several protein coding and also noncoding genes. Of those, C2CD4D, KIAA1949, IFFO1, TXNRD1, OTX2, PPP1R16B, PRDM16 and ALPL, were associated with several other malignancies including neuroblastoma,20 ovarian,21 lung,22 esophageal,23 and prostate24 cancers. Several markers have been previously shown to be associated with BC.9, 25-39 The protein kinase CDKL2 was reported to be hypermethylated in HER2-positive BC tissues compared to normal breast tissues.40 Its differential methylation was associated with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with TNBC.25 For SPAG6, a higher promoter methylation was observed in serum samples of women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and early invasive BC (pT1 tumors) compared to those from controls with benign disease. SPAG6 methylation in combination with the PER1, ITIH5 and NKX2-6 genes was introduced as a promising blood-borne epigenetic biomarker for minimally invasive BC detection,26 with an AUC of 0.718.

Promoter methylation of SFRP5, a modulator of Wnt signaling, was shown in 72.6% of breast tumor tissues, whereas it was unmethylated in normal breast tissues.27 The same study also showed that SFRP5 promoter methylation is associated with survival of BC patients. Patients with a methylated SFRP5 promoter had a reduced survival compared to those having an unmethylated promoter. For SPHK2, a higher promoter methylation was observed in BRCA1-like breast tumors (the BRCA1-methylation-associated BRCA1-like subgroup), the majority of which are triple negative, compared to the non-BRCA1-like BCs. This finding suggests that hypermethylation of SPHK2 may be specific for this BC subgroup.29 CPXM1 is an epigenetic marker for BC detection in liquid biopsies.30 In a study on the development of BC detection models using 16 epigenetic markers, the best model adopted four methylation markers including CPXM11 and distinguished BC cases from controls with high accuracy.

In the present study, we applied machine learning classifier to differentiate TNBC patients from healthy controls and selected highly discriminative CpG sites based on their contribution to the model performance. The underlying XGBoost classification algorithm has successfully been used for DNA methylation studies in other cancer entities41, 42 and allows an effective feature selection by calculating the contribution of each CpG sites on individual classification trees of the model. Applying this strategy allowed us to reduce the number of DMRs to be tested on cfDNA samples from 23 to 6 and further select the top three ones providing the best diagnostic performance. The top three DMRs, which overlapped with the SPAG6, LINC10606 and TBCD/ZNF750 genes, showed significant differences in the cfDNA levels between TNBC cases and healthy controls. A methylation score obtained by combining these three DMRs had the highest discriminative accuracy (AUC = 0.78 and 0.74 for test and validation sets, respectively). In a previous study on metastatic TNBC, an AUC of 0.92 was reported using a next-generation sequencing (NGS) methylation-based blood test.32 In another study, a DNA methylation-based epigenetic signature of breast DNA was described using three methylation markers.43 The later study was performed on plasma samples of BC patients with metastatic and localized disease and reported an AUC of 0.9 and 0.91, respectively. Although better diagnostic performance was reported in the previous studies, notably, our TNBC samples were mainly from patients with nonmetastatic tumors, which release less ctDNA. Our findings might be more clinically valuable, as earlier detection of BC before metastatic spread is critical for cure. In a multicancer early detection study, BC was found to be among the cancer types with low overall sensitivity for detection (30.5%), suggesting that breast tumors release less cfDNA into the bloodstream and are therefore more difficult to detect.44

In addition, we found significant differences in methylation levels at 16 CpG sites in 10 DMRs between low/intermediate and high grade tumors. The observed differential methylation levels at these DMRs in grade 3 tumors compared to grade 1/grade 2 tumors suggest that methylation levels at these regions may be useful as biomarkers for prognosis of TNBC.

Our study has some limitations. The DNA methylation biomarkers were identified in retrospective sample sets of TNBC cases and controls. Future prospective studies are needed to investigate whether these markers are also applicable for early detection of disease. Second, in our study, we only assessed the diagnostic performance of methylation biomarkers for TNBC, which was acceptable. However, to increase diagnostic performance, these markers have to be analyzed in a multimodal liquid biopsy in combination with other circulating biomarkers, such as cancer-derived mutations in cfDNA, fragmentation profile, exosomes, miRNA, proteins and circulating tumor cells. Third, in our study, only the TNBC subtype was analyzed. Studies on other BC subtypes are also needed to evaluate whether the methylation biomarkers are specific for TNBC.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study directed towards the identification of methylation biomarkers for TNBC, in which genome-wide DNA methylation data of tumor and normal breast tissues adjusted for cell type heterogeneity were evaluated. We have identified aberrant methylation at 23 genomic regions in TNBC tissues compared to normal breast tissues and have confirmed the findings at six top DMRs on plasma-derived cfDNA samples of TNBC patients and controls. Our findings suggests that aberrant DNA methylation at these regions may serve as sensitive and specific biomarkers for noninvasive diagnosis of TNBC. Independent studies with larger sample sizes should be performed to further validate the identified biomarkers for TNBC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mehdi Manoochehri: Conception and design of the study; Analysis and interpretation of data; Writing of the article. Nasim Borhani: Analysis and interpretation of data. Clarissa Gerhäuser: Conception and design of the study; Analysis and interpretation of data; Writing of the article. Yassen Assenov: Analysis and interpretation of data. Maximilian Schönung: Analysis and interpretation of data; Writing of the article. Thomas Hielscher: Analysis and interpretation of data; Writing of the article. Brock C. Christensen: Provision of study material or patients. Min Kyung Lee: Provision of study material or patients. Hermann-Josef Gröne: Analysis and interpretation of data. Daniel B. Lipka: Analysis and interpretation of data. Thomas Brüning: Provision of study material or patients. Hiltrud Brauch: Provision of study material or patients. Yon-Dschun Ko: Provision of study material or patients. Ute Hamann: Conception and design of the study; Analysis and interpretation of data; Writing of the article. The work reported in the article has been performed by the authors, unless clearly specified in the text. Final approval of article: All authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all study participants, clinicians, family doctors, researchers and technicians for their contributions and commitment to our study. The GENICA Network: Molecular Genetics of Breast Cancer, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany (UH); Dr. Margarete Fischer-Bosch Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, Stuttgart and University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany (HB, W-Y Lo, R Hoppe, S Winter); German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) and German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) im Rahmen der Exzellenzstrategie des Bundes und der Länder - EXC 2180 - 390900677 [HB]; Department of Internal Medicine, Evangelische Kliniken Bonn gGmbH, Johanniter Krankenhaus, Bonn, Germany (Y-DK, C Baisch); Institute of Pathology, University of Bonn, Germany (H-P Fischer); Institute for Prevention and Occupational Medicine of the German Social Accident Insurance, Institute of the Ruhr University Bochum (IPA), Bochum, Germany (TB, B Pesch, S Rabstein, A Lotz); and Institute of Occupational Medicine and Maritime Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany (V Harth). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The work was funded by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in studies involving human were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration. Informed consent was obtained for all study participants. SKKDKFZS was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg (Ethics vote number S-079/2008).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Human Methylation450K BeadChip and EPIC array data generated in our study have been uploaded to GEO under the accession number GSE207998. Other data that support the findings of our study are available from the corresponding author upon request.