Effectiveness of Cucumis sativus L. Supplementation on Mood, Anxiety, and Sleep Quality: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims

Despite widespread use, more research is needed to assess the health effects of herbal plants. Preliminary research indicates that cucumber extract (Cucumis sativus L.) is safe and may exhibit analgesic properties for joint pain, but studies on its impact on other health-related outcomes—including mood, sleep, and health-related quality of life—are lacking. As part of a larger investigation, this study examined the effectiveness of a standardized powder of Cucumis sativus L. (Q-actin) on mood, anxiety, health-related quality of life, and sleep quality.

Methods

In this CONSORT-compliant double-blind placebo-controlled trial, 80 adults (M age = 50.10) were randomized to either the Cucumis sativus L. Group (CG; 20 mg/day) or Placebo Group (PG; rice protein, 20 mg/day) for 60 days. Participants completed the Prolife of Mood States, Trait Anxiety Inventory, Perceived Stress Scale, Health-related Quality of Life Scale, and Flinder's Fatigue Scale at Baseline, Day 15, Day 30, and Day 60. Daily assessments of adherence and adverse events were obtained. Data were collected from May 2024 to August 2024, stored electronically, and analyzed using general linear models and nonparametric tests.

Results

Significant main effects for Time and Condition (p's < 0.001) were observed, indicating overall improvements across time and differences between groups. Although the interaction effects were not significant, the CG showed greater improvements than the PG in fatigue, mood, sleep quality, perceived stress, anxiety, and health-related quality of life. No adverse effects were reported.

Conclusion

Cucumis sativus L. shows potential as a herbal intervention for improving mood, sleep quality, and anxiety. However, due to the lack of significant group-by-time interaction effects, these results should be interpreted with caution. Larger, well-powered clinical trials are needed to confirm its efficacy across diverse populations and settings.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06246383.

1 Introduction

Cucumis sativus L. (cucumber; family Cucurbitaceae) is a widely consumed plant known for its high content of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, and triterpenoids, which contribute to its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and lipid-lowering properties [1, 2]. Preliminary research has found that C. sativus L. supplementation is effective for reducing pain in adults with moderate knee osteoarthritis [3, 4]. The pharmacological effects of C. sativus L. along with its pain-reducing effects, suggest potential benefits for health-related quality of life, as oxidative stress and inflammation are linked to negative moods such as anxiety, depression, and stress, along with poor sleep quality and increased daytime fatigue, especially with aging adults [5, 6]. Despite these promising characteristics, research on C. sativus L.'s specific impact on psychological health and sleep remains sparse.

These effects may be particularly relevant to the aging population, where the prevalence of sleep disturbances, mood dysregulation, and anxiety increases significantly and are intertwined [7]. Aging is often associated with heightened inflammation and oxidative stress, which increase sleep problems, anxiety, and negative mood. The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of C. sativus L. could offer a therapeutic strategy for managing these age-related issues, potentially reducing the reliance on pharmaceutical interventions. Moreover, as aging adults experience declines in physical and mental health, maintaining quality sleep and managing anxiety and mood becomes crucial for preserving health-related quality of life.

Previous studies on plant-based interventions have shown that specific bioactive compounds can modulate neurotransmitter levels, promote relaxation, and improve sleep quality [8]. And recent investigations into the effects of various plant-based supplements have shown promise in improving mood, sleep, and anxiety symptoms [9], highlighting the need for further exploration. C. sativus L., rich in bioactive components, may offer a unique approach to enhancing mood, health-related quality of life, and sleep by targeting these mechanisms.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a 60-day randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of daily use of an aqueous extract of cucumber (C. sativus L., Q-actin) supplementation compared to placebo on health-related quality of life, mood, sleep, and anxiety in adults. Q-actin is a cucumber extract with the anti-inflammatory iminosugar idoBR1 standardised to over 1%. These iminosugars can act as secondary messengers to reduce the inflammation process [2, 10]. The primary outcome was sleep quality, and the secondary outcomes were health-related quality of life, mood, and anxiety. By examining psychological (anxiety, mood) and sleep outcomes, this study fills a gap in understanding C. sativus L.'s potential as a complementary therapy, especially for addressing the psychological and sleep challenges commonly faced by aging individuals.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

The trial followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines to ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting of randomized controlled trials [11]. Ethical approval was obtained from the Sterling Institutional Review Board (11651), adhering to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06246383). It was designed as a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either the intervention or placebo, with group assignment determined by a computer-based program to maintain allocation concealment and prevent selection bias. A research assistant generated the random allocation sequence, enrolled participants, and managed group assignments. The independent variable was C. sativus L. dietary supplementation, while the dependent outcomes variables were mood (i.e., Profile of Mood States), stress (i.e., Perceived Stress Scale), anxiety (i.e., Trait Anxiety Inventory), daytime fatigue (i.e., Flinder's Daytime Fatigue Scale), health-related quality of life (CDC Health-related Quality of Life Scale), and sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index). Based on prior research on C. sativus L.'s effects on pain [3, 4], a medium effect size was anticipated, and power calculations indicated a required sample size of 35 participants per group to achieve 80% power with an alpha of 0.05. Although pain was not a primary outcome in this study, these studies provided the most relevant available data at the time of trial design. Pain shares common underlying mechanisms with several outcomes assessed in the present study, and the medium effect size served as a conservative and widely accepted estimate in the absence of directly comparable prior data. Power calculations indicated a required sample size of 35 participants per group to achieve 80% power with an alpha of 0.05.

2.2 Participants

Participants were 81 adults (n = 27 men and n = 54 women, M age = 50.1 years).

2.3 Exclusion Criteria

Individuals meeting any of the following criteria were excluded from participation: (1) serious medical problems (e.g., mood disorders, current cancer case, severe rheumatoid arthritis, recent heart attack, recent stroke, or other disease that would interfere with study participation); (2) taking other medications (e.g., analgesic gels, arthritis medications, other anti-inflammatory drugs) or supplements (in particular, glucosamine and chondroitin) for joint pain for the previous month; (3) recent highly stressful events within 4 weeks of baseline; (4) regular use of NSAID during the previous 2 weeks of baseline; (5) unable to walk for at least 6 min at a moderate-to brisk pace; (6) current hormone therapy; (7) excessive alcohol consumption (defined as more than 14 standard drinks per week for men or 7 for women, or binge drinking within the past 3 months); (8) use of cigarettes or tobacco products within the past 30 days; (9) elevated caffeine intake over the past month (exceeding 400 mg per day); excessive alcohol consumption; (10) pregnancy, attempts at conception, or breastfeeding; (11) no joint pain; and (12) individuals deemed incompatible with the study protocol.

2.4 Procedures

After completing the initial screening process, eligible participants provided informed consent, before being enrolled in the study. Participants completed standardized, psychometrically validated self-report questionnaires at baseline (Day 0), Day 15, Day 30, and Day 60. To monitor compliance and document any adverse events, participants also kept a daily log. The self-report questionnaires were administered via a secure SurveyMonkey link sent through email or text message, with each survey taking approximately 25 min to complete at each assessment point. Participants were instructed to maintain their usual lifestyle habits and to avoid initiating any new exercise routines, dietary changes, or health interventions for the duration of the study. This information was gathered through self-report measures. Data collection occurred between May 2024 and August 2024, and all data were securely stored in electronic format. No modifications were made to the predefined trial outcomes once the study began, as all endpoints were established in the initial trial protocol and adhered to throughout the study period.

2.5 Intervention

As part of a larger study examining the effects of supplements on joint pain, the study utilized a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Participants were assigned using an automated randomization procedure conducted through SPSS software, resulting in the following two groups: (1) C. sativus L. intervention group (CG) and (2) placebo control group (PG). For the 60-day study duration, participants consumed 20 mg per day of their respective treatments. The 20 mg dosage of Q-actin was selected based on prior published studies demonstrating efficacy and safety at this level in human populations [3, 4]. In addition, this dose falls within the range generally recognized as safe for dietary supplement use and is consistent with the manufacturer's recommended daily intake. The intervention group received an aqueous ethanol extract of C. sativus L. standardized to contain over 1% ido-BR1, a unique iminosugar that contributes to the extract's anti-inflammatory properties, supporting joint health and mobility. The extract, known as Q-actin, was provided by Gateway Health Alliances Inc. (Fairfield, CA, USA) and is a concentrated 12:1 extract, meaning each unit represents 12 times the amount of dried fruit. The supplement is compliant with cGMP standards and certified Kosher, Halal, and ISO 9001:2015. The placebo contained rice protein as the inactive substance.

The placebo, composed of rice protein, was selected for its inert nature and lack of bioactive compounds relevant to the study outcomes. It has a neutral inflammatory profile, low allergenicity, and an excellent safety record. Additionally, its appearance, texture, and mouthfeel closely matched the active supplement, helping to preserve the integrity of blinding.

2.6 Adverse Events

The supplement was well-tolerated, with no reported adverse events.

2.7 Blinding

To maintain blinding, Gateway Health Alliances labeled the supplement and placebo bottles as “A” or “B”, ensuring that both were identical in appearance, odor, and size. The research team remained blinded to group assignments until the study concluded. Following the final assessment, both the research team and participants were unblinded and informed of their respective treatment allocations.

2.8 Supplement Information and Adherence

Participants were instructed to take the capsules approximately 30 min before bedtime. Adherence was monitored through a daily questionnaire that recorded supplement intake. To promote compliance, participants received daily text reminders to follow the supplement regimen as directed.

2.9 Adherence

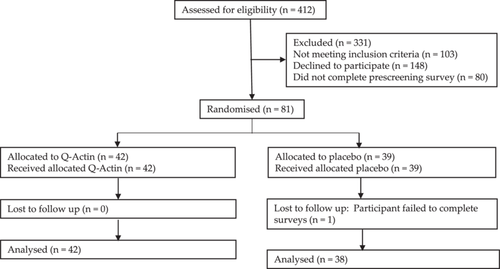

Of the 81 participants who enrolled and provided consent, 80 completed the trial, resulting in a completion rate of 98.7%. This rate accounts for one dropout from the PG due to loss of follow-up (i.e., failure to complete the surveys; see Table 1 and Figure 1).

| Demographic variable | Cucumis sativus L. group (N = 42) | Placebo group (N = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.10 (7.0) | 50.20 (8.8) |

| Body mass index | 27 (5.1) | 26 (4.1) |

| Number (%) female | 28, 66.7% | 26, 60.5% |

| Ethnicity (number, %) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 38, 90% | 36, 84% |

| Asian | 1, 2% | 4, 9% |

| Hispanic | 2, 5% | 2, 5% |

| Black/African American | 1, 2% | 1, 2% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 50.1 (7.0) | 50.2 (8.8) |

2.10 Statistical Analysis

Before analysis, the data were examined for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables that showed a significant deviation from normality (p < 0.05) were log10-transformed to reduce skewness and meet the assumptions of normality required for parametric testing. Transformed values were then used in the analyses. Results are presented using the transformed values, but back-transformed values are shown in figures and tables for interpretability. Continuous data were presented as mean (SD) and analyzed using 2 (Group) × 3 (Time: Day 15, Day 30, and Day 60) repeated measures ANCOVA, with baseline scores included as the covariate. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Sidak adjustment. Post hoc tests were paired-sample t-tests where applicable. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test and expressed as counts/percentages where appropriate. Moderator analysis of gender was assessed via a 2 (Gender) × 2 (Group) × 3 (Time) repeated measures ANCOVA. Statistical analyses were performed using Excel and Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) (version 28).

3 Measures

3.1 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index is a standardized, self-administered questionnaire that evaluates retrospective sleep quality and disturbances. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index consists of 19 items forming the following seven subscales: (1) sleep quality, (2) sleep latency, (3) sleep duration, (4) sleep efficiency, (5) sleep disturbance, (6) sleep medication, and (7) daily dysfunction. Each item has a score that ranges from 0 to 3. The scores of seven components are summed to yield a global score ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality [12].

3.2 Profile of Mood States (POMS)

The POMS-40 was used to measure mood states including tension, anger, vigor, fatigue, depression, and confusion. A total mood score was computed by summing the values for tension, depression, anxiety, fatigue, and confusion, and then subtracting the vigor subscale score. The items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The POMS-40 has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties [13].

3.3 Trait Anxiety Inventory

The Trait Anxiety Inventory (20 items) assesses general feelings of anxiety, such as calmness, confidence, and security [14]. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety levels. The items are assessed on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much so), resulting in a possible score range of 0–60. The inventory has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

3.4 Flinders Fatigue Scale

The Flinders Fatigue Scale is a 7-item scale that measures various characteristics of fatigue (e.g., frequency, severity) experienced. The items tap into commonly reported themes of how problematic fatigue is, the consequences of fatigue, frequency, severity, and insomnia patients' perception of fatigue's association with sleep [15]. Six items are presented in Likert format, with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Item 5 measures the time of day when fatigue is experienced and uses a multiple-item checklist. Respondents can indicate more than one response for item 5, and it is scored as the sum of all times of the day indicated by the respondent. One item explicitly asks for respondents' impression of whether they attribute their fatigue to their sleep. Total fatigue is calculated as the sum of all individual items. Total fatigue scores range from 0 to 31, with higher scores indicating greater fatigue. A clear description of the term “fatigue” is provided in the initial instructions to the scale.

3.5 Perceived Stress Scale

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress [16]. It is a measure of the degree to which situations in one's life are appraised as stressful. Items were designed to tap how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives. The scale also includes direct queries about current levels of experienced stress. The PSS was designed for use in community samples with at least a junior high school education. The items are easy to understand, and the response alternatives are simple to grasp. Moreover, the questions are of a general nature and hence are relatively free of content specific to any subpopulation group. The questions in the PSS ask about feelings and thoughts during the last month. In each case, respondents are asked how often they felt a certain way.

3.6 Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

The CDC Health-related Quality of Life measure will be used to assess health-related quality of life [17]. The scale assesses overall health-related quality of life, including physical health, mental health, sleep quality, pain, and energy. This scale has excellent psychometric properties [18].

3.7 Daily Diary

The daily diary was used to assess adverse events and adherence.

4 Results

For the Flinder's Fatigue Scale significant condition, F(1, 77) = 32.14, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 17.85, p < 0.001, main effects were evidenced, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 0.62, p = 0.60 (see Table 2). Post hoc analyses revealed significant improvements in daytime fatigue from Baseline to Day 60 for the CG, p = 0.04.

| Outcome | Cucumis sativus L. group | Placebo group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number = 42 | Number = 38 | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Day 0 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 60 | Day 0 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 60 | |

| Flinder's daytime fatigue | 13.76 (7.21) | 11.85 (6.90) | 11.39 (5.85) | 10.59* (6.12) | 9.95 (5.21) | 9.82 (5.80) | 8.82 (5.85) | 9.77 (5.68) |

| Profile of mood states | 154.19 (14.56) | 154.48 (15.29) | 151.45 (12.54) | 149.94 (12.15) | 152.76 (8.65) | 152.03 (10.58) | 151.61 (10.50) | 151.00 (10.23) |

| Trait anxiety scale | 47.94 (11.66) | 44.31 (13.58) | 40.30* (12.02) | 40.55* (12.44) | 43.51 (11.93) | 44.47 (10.46) | 42.37 (11.20) | 41.72 (11.11) |

| Perceived stress scale | 5.21 (3.31) | 5.67 (3.15) | 4.33 (2.88) | 4.65 (3.06) | 4.71 (2.43) | 4.50 (2.53) | 4.45 (2.62) | 4.26 (2.73) |

| Pittsburgh sleep quality scale | 1.38 (0.58) | 1.27 (0.59) | 1.20 (0.55) | 1.15 (0.65) | 1.24 (0.68) | 1.21 (0.729) | 1.24 (0.59) | 1.17 (0.55) |

- Note: Lower scores for all the measures indicate an improvement.

- * Denotes significant difference (p < 0.05) between baseline and the different time points within the same group.

For the Profile of Mood States significant condition, F(1, 77) = 85.52, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 35.34, p < 0.001, main effects were found, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 0.61, p = 0.61. Mood improved over time for the CG, albeit nonsignificant.

For the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index significant condition, F(1, 77) = 75.05, p < 0.001, and time, F (3, 231) = 35.42, p < 0.001, main effects were evidenced, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 0.78, p = 0.51. Sleep quality improved more for the CG compared to the PG, albeit nonsignificant. The percent change from Baseline to Day 60 was 23.32% for CG compared to 2.36% for the PG (see Table 3).

| % Change from baseline | Cucumis Sativus L. group N = 42 | Placebo group N = 38 |

|---|---|---|

| Pittsburgh sleep quality index | 23.32% | 2.36% |

| Profile of mood states | 1.87% | 1.01% |

| Trait anxiety scale | 10.68% | 0.52% |

| Perceived stress scale | 47.39% | 10.72% |

| Flinder's daytime fatigue scale | 0.96% | 10.18% |

| HRQoL general health | 12.80% | 6.64% |

| HRQoL physical health | −15.82% | −24.94% |

| HRQoL mental health | −36.94%* | −7.30% |

| HRQoL health prevented activities | −27.03% | 6.75% |

| HRQoL pain made activities difficult | −11.00% | 20.19% |

| HRQoL felt sad | −30.93% | 2.70% |

| HRQoL felt worried | 4*4.57% | 38.49% |

| HRQoL felt not enough rest | 10.60% | −11.70% |

| HRQoL felt healthy | 68.31% | 34.51% |

- Abbreviation: HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

- * p < 0.05.

For the Perceived Stress Scale, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 49.05, and time, p < 0.001, F(3, 231) = 21.37, p < 0.001, were evidenced, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 1.8, p = 0.15. Perceived stress improved more over time for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. The percent change from Baseline to Day 60 was 47.39% for the CG compared to 10.72% for the PG.

For Trait Anxiety, a significant main effect for condition, F(1, 77) = 27.63, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 15.84, p < 0.0001 was evidenced, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 1.16, p = 0.32. Post hoc analyses indicated significant improvements in anxiety for the CG from Baseline to Day 30 and Day 60, p's < 0.01. Trait anxiety had a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 10.68% for the CG compared to 0.52% for the CG.

For HRQoL General Health, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 53.71, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 31.99, p < 0.001, but not the interaction, F(3, 231) = 0.19, p = 0.904, were evidenced (see Table 4). General Health improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. General Health had a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 12.80% for the CG compared to 6.64% for the PG.

| Cucumis sativus L. group | Placebo group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number = 42 | Number = 38 | |||||||

| Outcome | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Day 0 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 60 | Day 0 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 60 | |

| General health | 3.29 (0.97) | 3.49 (0.83) | 3.48 (0.83) | 3.49 (0.93) | 3.45 (0.92) | 3.58 (0.92) | 3.61 (0.86) | 3.53 (0.80) |

| Physical health | 3.38 (3.83) | 2.94 (3.66) | 2.33 (2.95) | 2.67 (2.66) | 1.87 (3.15) | 1.63 (2.76) | 2.37 (3.79) | 1.43 (2.40) |

| Mental health | 2.81 (3.76) | 2.82 (3.18) | 2.10 (2.71) | 1.77 (2.74) | 2.11 (3.06) | 1.58 (2.51) | 2.00 (3.50) | 1.75 (2.35) |

| Poor Physical or mental health prevented activities | 3.05 (4.21) | 2.83* (3.38) | 1.73 (2.57) | 2.07 (3.09) | 1.26 (2.29) | 1.13 (2.24) | 0.87 1.61) | 1.14 2.38) |

| Pain made activities difficult | 4.67 (3.71) | 3.62 (3.57) | 3.31 (3.47) | 3.14 (2.88) | 2.61 (2.98) | 2.34 (3.55) | 2.50 (3.48) | 2.79 3.51) |

| Felt sad, blue, or depressed | 3.02 (4.17) | 2.55 (3.01) | 2.15 (2.70) | 2.02 (3.19) | 1.68 (2.79) | 1.39 (2.65) | 2.00 (3.34) | 1.92 (2.79) |

| Felt worried, tense, or anxious | 4.29 (4.28) | 4.40 (4.38) | 3.03 (3.67) | 3.34 (4.13) | 3.61 (3.75) | 3.29 (2.99) | 3.42 (3.52) | 3.66 (3.44) |

| Did not get enough sleep | 7.33 (4.22) | 6.17 (4.01) | 5.89 (3.99) | 5.98 (3.85) | 5.84 (4.08) | 6.45 (4.54) | 5.39 (4.10) | 5.32 (4.31) |

| Felt healthy and energetic | 4.29 (3.70) | 4.68 (3.61) | 5.55 (3.44) | 5.26 (3.82) | 5.53 (4.30) | 6.34 (4.01) | 6.63 (4.14) | 6.68 (4.27) |

- Note: Higher scores indicate an improvement for general health and feeling healthy and full of energy. For all other measures a lower score indicates an improvement.

For HRQoL Physical Health, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 21.73, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 5.74, p < 0.001, were found but nonsignificant interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 1.97, p = 0.12. Physical Health improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant.

For HRQoL Mental Health, Significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 12.55, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 4.64, p = 0.004, were found, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 1.96, p = 0.12. Mental Health improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Mental health had a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 36.94% for the CG compared to 7.30% for the PG.

For HRQoL Poor Physical or Mental Health Prevented Activities, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 32.55, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 10.89, p < 0.001, were found, but the interaction was nonsignificant, F(3, 231) = 2.02, p = 0.11. Poor physical or mental health preventing activities improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Physical or mental health prevented activities had a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 27.03% for the CG compared to a decrease of 6.75% for the CG.

For HRQoL Pain Making Activities More Difficult, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 23.88, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 7.19, p < 0.001, were found, but the interaction, F(3, 231) = 0.53, p = 0.65, was nonsignificant. Pain- Making Activities More Difficult improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Pain-making activities difficulties improved from Baseline to Day 60 by 11.00% for the CG compared to a worsening of 20.19% for the PG.

For HRQoL Feeling Sad, Blue, and Depressed, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 22.76, p < 0.001, Time, F(3, 231) = 9.05, p < 0.001, were found, but the Interaction, F(3, 231) = 1.18, p = 0.32, was nonsignificant. This outcome improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Feeling Sad, Blue, and Depressed had a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 30.93% for the CG compared to a worsening of 2.70% for the PG.

For HRQoL Feeling Worried, Tense, or Anxious, significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 31.29, p < 0.001, and Time, F(3, 231) = 14.35, p < 0.001, but the Interaction, F(3, 231) = 1.45, p = 0.22, was nonsignificant. This health outcome improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Found a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 44.57% for the CG compared to 38.49% for the PG.

For HRQoL Feeling did not get enough sleep, significant main effect for condition, F(1, 77) = 19.77, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 9.24, p < 0.001, but the interaction, F(3, 231) = 0.56, p = 0.64, was nonsignificant. This Health outcome improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Found a percent improvement of 10.60% for the CG compared to a decrease of 11.70% for the PG.

For HRQoL Feeling Healthy and Full of Energy significant main effects for condition, F(1, 77) = 52.82, p < 0.001, and time, F(3, 231) = 28.09, p < 0.001, but a nonsignificant interaction, F(3, 231) = 1.12, p = 0.34, was found. This Health improved more for the CG compared to PG, albeit nonsignificant. Feeling healthy and full of energy had a percent improvement from Baseline to Day 60 of 68.31% for the CG compared to 34.51% for the PG.

5 Discussion

Research has highlighted the anti-inflammatory, lipid-lowering, and antidiabetic properties of C. sativus L., and pilot trials have shown promising results in reducing pain among adults with joint pain [3, 19-21]. Although the interaction effects were not significant, this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that C. sativus L. supplementation (Q-actin) also resulted in improvements in mood, sleep quality, and HRQoL over 60 days, providing further insights into its potential role in mental health and sleep quality. Study findings, limitations, and potential future research directions are discussed below.

In this study, supplementation with C. sativus L. demonstrated improvements in various measures of health, including sleep quality, daytime fatigue, mood, stress, anxiety, and HRQoL compared to placebo. While participants in the supplement group reported greater health benefits, these improvements were often not significantly different from those observed in the PG. The results suggest that C. sativus L. extract may have a positive effect on these domains, though the placebo effect also played a notable role in perceived improvements. Further research with larger sample sizes and longer durations may be needed to establish the efficacy of C. sativus L. in enhancing these outcomes with greater statistical significance.

Consistent with other research [3, 19, 20], C. sativus L. was found to be safe and well-tolerated by participants. No adverse events were reported. Further research is needed in a variety of populations (e.g., varying ages and weights) to establish the generalizability of these results in both clinical and nonclinical populations.

Herbal supplements are gaining attention, particularly among aging adults, due to their potential health benefits and role in integrative medicine [22]. Traditionally used in healing systems, recent studies validate their efficacy in supporting immune function, cognitive health, mood regulation, and metabolism. Research has demonstrated their value in areas such as pain management, liver health, and skin conditions [23, 24]. As aging adults seek preventive care and alternatives to pharmaceuticals, rigorous research is essential to ensure standardized dosing, safety, and long-term benefits for personalized health strategies.

While randomization is designed to balance both measured and unmeasured confounders, some baseline variability between groups is expected, especially in studies with modest sample sizes. In our trial, the CG group showed higher baseline values in several measures, such as fatigue and physical health. Although these differences were not statistically significant, we acknowledge that they could influence the interpretation of treatment effects. To mitigate this potential confounding, we applied ANCOVA models that controlled for baseline scores. These analyses upheld the findings, suggesting that the observed benefits were attributable to the intervention rather than pre-existing group differences.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. The 60-day duration limited our ability to assess the long-term effects of C. sativus L. on health outcomes, necessitating future studies with extended follow-ups [25]. The sample size, though sufficient for the study's outcomes, may have been inadequate for subgroup analyses, and the reliance on self-reported measures introduces potential biases. While C. sativus L. was well-tolerated, more comprehensive safety assessments, especially regarding long-term use and interactions with other treatments, are needed to further establish its safety profile.

Furthermore, although the analyses indicated improvements in mood, sleep quality, and HRQoL among participants receiving the supplement, the interaction effects between time and treatment group were not statistically significant. This suggests that while both groups improved over time, the rate of change did not differ significantly between the intervention and placebo conditions. Several factors may contribute to the lack of interaction effects, including the duration of the study, sample size, and the potential influence of placebo-related improvements in perceived well-being. Similar patterns have been reported in other randomized controlled trials, where significant within-group improvements were observed across conditions, yet no significant time × treatment interactions emerged. These findings highlight the potential role of expectancy effects, regression to the mean, or natural symptom fluctuation in influencing perceived outcomes [26]. While this limits conclusions about differential efficacy over time, the consistent pattern of benefits observed in the supplement group supports the potential of C. sativus L. to positively impact mental health and sleep outcomes. Future studies with larger samples and extended durations are needed to better differentiate intervention effects from nonspecific improvements.

6 Conclusion

In summary, this study examined the efficacy of C. sativus L. on adults' mental health and sleep quality in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Although the interaction effects were not significant, the results revealed that C. sativus L. supplementation led to improved health-related quality of life, mood, sleep quality, and decreased anxiety and perceived stress levels. These preliminary findings suggest the potential of C. sativus L. as a beneficial supplement for overall health-related quality of life. C. sativus extract could serve as an effective alternative to synthetic antioxidants and anti-inflammatory drugs currently available [18]. Further research with larger sample sizes is needed for a comprehensive understanding of its mechanisms and long-term effects.

Author Contributions

Heather A. Hausenblas: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, writing – original draft, methodology, writing – review and editing, project administration, and supervision. David Hooper: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, software, formal analysis, data curation, supervision, and resources. Stephanie Hooper: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – review and editing, formal analysis, project administration, supervision.

Acknowledgments

This trial was funded in part by Gateway Health Alliances. Gateway Health Alliance had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, had full access to all of the data in this study, and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Transparency Statement

The lead author, Heather A. Hausenblas, affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request from the first author.