Striving toward safe abortion services in Nepal: A review of barriers and facilitators

Abstract

Background and Aims

Despite the decriminalization of abortion in Nepal in 2002, unsafe abortion is still a significant contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality. Nepal has witnessed a significant drop in abortion-related severe complications and maternal deaths owing to the legalization of abortion laws, lowered financial costs, and wider accessibility of safe abortion services (SAS). However, various factors such as sociocultural beliefs, financial constraints, geographical difficulties, and stigma act as barriers to the liberal accessibility of SAS. This review aimed to determine key barriers obstructing women's access to lawful, safe abortion care and identify facilitators that have improved access to and quality of abortion services.

Methods

A systematic search strategy utilizing the databases PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and Embase was used to include studies on the accessibility and safety of abortion services in Nepal. Data were extracted from included studies through close reading. Barriers and facilitators were then categorized into various themes and analyzed.

Results

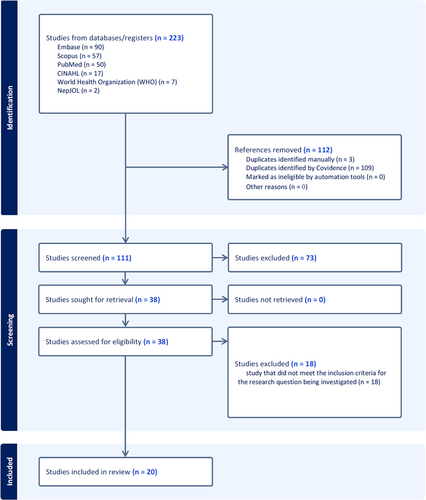

Of 223 studies, 112 were duplicates, 73 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 18 did not align with the research question; thus, 20 studies were included in the review. Various barriers to SAS in Nepal were categorized as economic, geographic, societal, legal/policy, socio-cultural, health systems, and other factors. Facilitators improving access were categorized as economic/geographic/societal, legal/policy, socio-cultural, and health systems factors. The patterns and trends of barriers and facilitators were analyzed, grouping them under legal/policy, socio-cultural, geographic/accessibility, and health systems factors.

Conclusion

The review identifies financial constraints, unfavorable geography, lack of infrastructure, and social stigmatization as major barriers to SAS. Economics and geography, legalization, improved access, reduced cost and active involvement of auxiliary nurse-midwives and community health volunteers are key facilitators.

Key points

-

The legalization of abortion in Nepal has not ensured universal access to safe services.

-

Stigma, lack of awareness, and negative attitude of providers hamper access.

-

Rural, low-income women face additional obstacles such as distance, cost and lack of confidentiality.

1 INTRODUCTION

Terminating a pregnancy before full term is reached is known as abortion. When the reasons for having an abortion do not align with legal justifications, it often results in women resorting to secret and unsafe abortions. In Nepal, unsafe abortion is considered a significant contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality. This can lead to serious complications such as injuries, hemorrhage, and sepsis, that can have a long-term detrimental effect on the mother's health. Additionally, using risky abortion methods may increase the chance of developing secondary infertility.1-4 Abortion was illegal in Nepal until 2002. In Nepal, approximately half of all maternal deaths caused by complications from unsafe abortions.5-9 Despite strict laws, a large number of unsafe abortions occur each year, reflected by the fact that one-third of all imprisoned women and half of all hospitalized women were due to the consequences of illegal termination of pregnancies.10, 11 Following amendments to the Penal Code in 2002, abortion was permitted on certain grounds.12-14 Under current law, a woman has the right to an abortion for any reason within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and up to 18 weeks in cases of sexual assault.15 Additionally, abortion at any gestational age is legally permitted if a doctor certifies that continued pregnancy endangers pregnant woman's physical and/or mental health; or that the fetus is deformed.5, 15 In 2018, a new law known as the Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health Rights Act (SMRHR) was enacted by Parliament to increase women's access to safe and legal abortion.16

In Nepal, safe abortion services (SAS) are available at the federal, provincial, and municipal levels, as well as through outreach programs.17 Public sector health facilities in the country offer free abortion care to the client and receive reimbursement ranging from 800 to 3000 Nepalese rupees from their respective provincial governments based on the service provided.17 These multiple efforts to encourage SAS across have resulted in a significant decline in maternal mortality ratio, that is, from 539 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 199618 to 151 per 100,000 live births in 2022.19 During the period from 2007 to 2010, a notable trend emerged: a significant reduction in the severity of complications caused by unsafe abortions.7

A study conducted in Nepal in 2014 analyzed the distribution of legal abortions across sectors and found that, approximately 37% occurred in public facilities, 34% in nongovernmental facilities, and the remaining 29% in private clinics.9 Interestingly, these statistics are influenced by the fact that unsafe abortion is the third most common cause of maternal mortality in Nepal.9

According to the data from the Ministry of Health and Population, in the fiscal year 2020/21, 79,952 women in Nepal utilized SAS. This represents a slight decrease from 87,869 women who used SAS in the previous fiscal year 2019/20; overall, SAS has shown a downward trend since a peak of 98,640 women accessing services in 2017/18.17

The global gag rule (GGR) prohibits non-US-based nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from providing, referring, or counseling abortion services that receive US global health assistance. It also prohibits advocating for abortion law reforms.20 GGR has fragmented sexual and reproductive health (SRH) service delivery in many countries, including Nepal.20 The broad scope of this policy affects funding allocation, posing challenges even for NGOs without direct US government funding. This disruption is consistent with pre-existing barriers to legal abortion, such as limited knowledge, stigma, cost, and limited access to services. In addition to abortion, GGR contributes to reducing contraceptive use, increases induced abortion, and has a chilling effect on advocacy efforts.21

This review aimed to identify barriers and facilitators affecting access to SAS in Nepal, focusing on major obstacles hindering women's access and identifying improvements in quality and accessibility.

2 METHODS

2.1 Research design

We utilized a systematic search strategy to identify relevant studies investigating the accessibility and safety of abortion services in Nepal.

2.2 Research question

The research question guiding the review was: “What are the barriers and facilitators for accessing safe abortion services in Nepal?”

2.2.1 Inclusion criteria

The studies included in this review satisfied the following requirements: (i) they were conducted in Nepal, (ii) they offered insights into abortion accessibility and safety, and (iii) they were published in peer-reviewed journals or recognized sources in the English language.

2.2.2 Exclusion criteria

To ensure the accuracy of our analysis, we specifically chose to include only studies written in English that reported original research findings and published before March 31, 2023. Additionally, we excluded studies such as reviews, commentaries, editorials, and letters that did not meet our inclusion criteria.

2.3 Database searched

To systematically search for literature on abortion access and saftey in Nepal, a syntax was created combining the following keywords: abortion, access, safety, Nepal.

(("abortion" OR "terminat*" OR "miscarriage*") AND ("access*" OR "availability" OR "utilization") AND ("safety" OR "complication*" OR "risk*") AND ("Nepal" OR "Nepali"))

We then systematically searched four databases: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus. In addition to these databases, a search of the grey literature was also conducted, which included difficult-to-find sources such as conference proceedings, government reports, and dissertations. This search was carried out using the World Health Organization Global Health Library as well as other sources such as Nepalese medical journals and databases including the Nepal Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Nepal Journals Online (NepJoL).

2.4 Data extraction

Identified studies underwent title/abstract and full-text screening for eligibility. Data were extracted from included studies through close reading. Barriers and facilitators were categorized into themes. Patterns and trends were analyzed across themes to synthesize insights on factors impacting abortion safety and accessibility in Nepal.

2.5 Ethical clearance

Ethical clearence is not applicaple as this study reviewed published studies.

3 RESULTS

A total of 223 studies were retrieved from the search of databases, of which 112 were removed as duplicates. The remaining 111 studies were then evaluated for the inclusion criteria, which led to the further exclusion of 73 studies. Subsequently, the full texts of 38 studies underwent evaluation for eligibility, ultimately resulting in the inclusion of 20 studies (Supporting Information S1: File 1) that aligned with the research question and met the specified inclusion criteria.7-9, 22-38 Flow diagram of the study design process is depicted in Figure 1.

We identified various barriers to SAS in Nepal, categorized as: economic, geographic, societal; legal/policy; sociocultural; healthcare systems; and other factors (Table 1). In the category of “economic, geographic, and social barriers,” major factors that barred access to SAS included financial constraints, high cost of abortion services in private clinics, limited availability of resources and infrastructure in rural areas, distance and transportation barriers, and lack of availability and accessibility to abortion services. The legal and policy barriers included a lack of knowledge about the law and SAS, fear of legal consequences, and legal restrictions. Other barriers include societal norms that stigmatize and discriminate against this form of healthcare, negative attitudes from healthcare providers, and cultural beliefs that perpetuate gender-based power imbalances. Furthermore, inadequate knowledge and training of providers, limited privacy and confidentiality, and insufficient resources also contribute to hindering access to medical abortion.

| Barriers |

|---|

| Economic, geographic, and societal factors |

| Scarcity of resources and infrastructure in rural areas8, 9, 25, 32 |

| Distance and transportation hindering access to service providers30, 33 |

| Financial constraints8, 34 |

| Limited availability and accessibility of service in rural areas7, 24 |

| High cost of abortion services in private clinics7, 23-25, 30, 33 |

| Legal and policy factors |

| Lack of knowledge of the law and availability of SAS8 |

| Fear of legal consequences or social stigma for seeking an abortion7, 8 |

| Legal restrictions24, 34, 37 |

| Restricted legal status of abortion where access to safe care is limited35 |

| A policy that bars women living more than 2 h from a health facility from using medical abortion28 |

| Challenges in obtaining necessary documents and approvals38 |

| Social and cultural factors |

| Stigma and discrimination against women seeking abortion8, 25, 30 |

| Stigma surrounding abortion32, 33, 38 |

| Negative attitudes from providers28, 29 |

| Sociocultural factors such as cultural beliefs34 |

| Sociocultural factors such as gender-based power dynamics and lack of decision-making power for women34 |

| Fear of judgment or discrimination from healthcare providers or others in the community23, 24 |

| Healthcare system factors |

| Lack of knowledge about abortion and available services8, 22, 33 |

| Lack of trained providers8, 34 |

| Inadequate knowledge and experience about the services required23 |

| Lack of confidentiality and privacy in healthcare settings7, 23, 35 |

| Inadequate capacity to meet the needs of the population26 |

| Inadequate training and resources for healthcare providers22, 25 |

| Limited availability of trained providers and facilities8, 30, 38 |

| Lack of service providers and physician oversight31 |

| Challenges in accessing effective postabortion contraception34 |

| Inadequate or inaccurate information and unsafe medications provided by untrained pharmacy workers, and the lack of a formal referral mechanism26, 35 |

| Other factors |

| Lack of awareness of abortion laws and services7, 29, 32, 34 |

| Lack of knowledge about contraception and social norms regarding sons22, 27 |

| Women resorting to covert and unsafe traditional procedures or self-induced abortion22, 37 |

| Abortions being performed for the wrong reasons26 |

| Misuse of services, particularly by women not using family planning methods26 |

| Sex-selective abortions and abortions used as a family planning method26 |

| Limited access to trained providers and equipment, particularly in remote areas34, 35, 37 |

| Women's lack of knowledge about their legal rights30 |

| Lack of counselors28 |

| Lack of formal referral networks for women who have been denied abortion services elsewhere29 |

| Lack of awareness of medical abortifacients among healthcare providers, prescription of varieties of allopathic and indigenous medicines by private providers and chemists for inducing abortion36 |

Facilitators improving access were categorized as: economic/geographic/societal; legal/policy; sociocultural; and healthcare systems factors (Table 2). The economic and geographical factors were the primary drivers in promoting accessibility to abortion services. The factors that were found to aid in the success of abortion services were the lowered cost, greater availability of SAS in rural communities, and the crucial roles played by auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANM) and community health volunteers (CHV) in rural areas. The legal and policy facilitators included the legalization of abortion, government efforts to increase access to SAS, partnerships between government and NGOs, and increased awareness and education about abortion laws and services. Social and cultural facilitators included increased awareness and education about SAS, parental involvement in communication about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) with adolescents, availability of adolescent-friendly healthcare services, confidential and nonjudgmental care provided by trained staff, supportive partners, friends, or family members, and the availability of information about SAS. The facilitators of the healthcare system included providing information and counseling to women seeking abortion care, training women CHV, increasing availability of medical abortion pills, pharmacy provision of abortion medications, training and support for non-clinicians, expansion of SAS, training of providers, and established referral networks for women who have been denied abortion services elsewhere.

| Facilitators |

|---|

| Economic, geographic, and societal factors |

| Reduction in the cost of abortion services24 |

| Improving access to SAS in rural areas7 |

| Improved access to SAS in rural areas7, 24 |

| Participation of auxiliary nurse midwives, and community health volunteers in rural areas33 |

| Legal and policy factors |

| Legalization of abortion25, 38 |

| Government efforts to increase access to SAS33 |

| Partnerships between government and NGOs to increase awareness and access to SAS33 |

| Improved awareness and education about abortion laws and services26 |

| Social and cultural factors |

| Increased awareness and education about SAS7, 24, 25, 33 |

| Parental involvement in communication about SRH with adolescents23 |

| Availability of adolescent-friendly health services23 |

| Confidential and nonjudgmental care provided by trained staff23 |

| Supportive partners, friends, or family members, and the availability of information32 |

| Positive views of healthcare staff and abortion service providers toward the new abortion law and practice26 |

| Healthcare system factors |

| Providing information and counseling to women seeking abortion care24 |

| Training female community health volunteers to provide information and referrals28 |

| Increased availability of medical abortion pills25, 33, 38 |

| Pharmacy provision of medical abortion9, 33, 35 |

| Training and support for nonphysician clinicians33, 35 |

| Expansion of SAS and provider training7, 25 |

| Established referral networks for women who have been denied abortion services elsewhere29 |

| Consistent access to medication for abortion29 |

| Improved training for providers29 |

| Increased confidentiality and privacy in healthcare settings7, 24 |

| Reduced stigma surrounding abortion7 |

| Support from local and international organizations to improve access to SAS25 |

| Training and mobilization of mid-level health workers, such as auxiliary nurse midwives31 |

| Human resources (trained ANM) and contraceptive supplies22 |

| Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of SAS to ensure that they are effective and equitable9 |

- Abbreviations: ANM, auxiliary nurse-midwives; NGO, nongovernmental organization; SAS, safe abortion services; SRH, sexual and reproductive health.

We analyzed the patterns and trends of barriers and facilitators, grouping them under legal/policy, sociocultural, geographic/accessibility, and healthcare systems factors (Table 3).

| Factors | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Legal and policy factors | Legal restrictions and policy barriers | Increasing support and cooperation between government and NGOs |

| Limited access to necessary documentation and approvals | Improvements in awareness and education about abortion laws and services | |

| Strict legal sanctions against abortion | Increasing implementation of the new abortion law and services | |

| Social and cultural factors | Stigma and discrimination against women | Increasing involvement of family and community members in communication |

| Sociocultural beliefs and gender-based factors | Increasing the availability of adolescent-friendly health services | |

| Lack of awareness and knowledge about safe abortion services | Reduction in stigma surrounding abortion and more positive views | |

| Geographic and accessibility factors | Limited availability and accessibility of safe abortion services | Ensuring safe abortion services accessible in rural areas |

| Distance and transportation barriers | Increasing awareness and provision of information and counseling | |

| Lack of access to trained providers and equipment | Cost reduction and improved training for providers | |

| Healthcare system factors | Limited infrastructure and resources in rural areas | Expansion and improvements in safe abortion services and training |

| Inadequate knowledge and experience about the services required | Increasing availability and access to medical abortion pills | |

| High cost of abortion services | Improvements in confidentiality, privacy, and support for clinicians |

- Abbreviation: NGO, nongovernmental organization.

4 DISCUSSION

Our comprehensive review of barriers and facilitators revealed four predominant factors impacting access to safe and legal abortion services in Nepal. These interrelated factors span across multiple spheres and require coordinated strategies.

4.1 Legal and policy factors

In various studies, a common barrier that was consistently found was a lack of understanding of abortion laws and service availability.7, 8, 23, 25, 32, 34, 37, 38 This leaves women unaware of their rights and options,8 which ultimately leads to uncertainty, fear of legal repercussions, and stigma. Additionally, the spread of misinformation exacerbates misconceptions.7, 8

Strict legal restrictions pose significant challenges, making it very difficult for women to freely make choices about their own bodies and reproductive health.24, 34, 37 Particularly, in lower-income settings such as Nepal, restrictive legal status increases disparities in accessing safe abortion care.35 Thankfully, the policy landscape has changed over the past two decades as abortion laws have become more liberal.25, 38 This has led to a significant shift toward recognizing women's reproductive health and that abortion is their fundamental right.

Despite these advances in the legal framework, barriers to access to abortion care remain. The policy requiring women who live far from healthcare facilities to obtain physician approval for medical abortion is an example of barriers that disproportionately affect rural populations.28 This restriction may increase inequalities. However, its recent amendment allows community healthcare workers to provide medical abortion, a promising policy change to expand access.17

It is critical to comprehensively address the complex legal and policy barriers to protect and uphold women's reproductive health and rights. To achieve equitable and safe access to abortion, it is important that strategies not only address ongoing restrictions, but also tackle existing awareness gaps and inequities. This requires coordinated efforts across sectors to establish an enabling environment for all individuals to exercise their right to abortion.33

Key facilitators such as legalizing abortion were transformative in decriminalizing the procedure and acknowledging women's autonomy.25, 38 Government–NGO partnerships have successfully increased awareness and availability of services.33 Better education on abortion laws and services also empowers women by giving them accurate information about their rights and options.26

4.2 Social and cultural factors

In Nepal, deeply rooted societal customs, values, and mindsets continue to uphold a harmful stigma surrounding abortion, impeding women's ability to access safe and necessary services.8, 23-25, 28, 30, 32-34, 38 This stigma originates from deeply ingrained patriarchal beliefs of women's morals and sexuality, which makes abortion taboo in our culture.34 It manifests itself through social isolation, verbal abuse, denial of services, and community disapproval of women seeking abortion.23, 24 Beyond emotional distress, stigma deters timely care-seeking, compels unsafe procedures, and hinders women's ability to reach/afford services.32, 33, 38

Persistent gender inequities and limited control over reproductive decisions act as catalysts for perpetuation of stigma.34 As a result, women are left with few options and often resort to unsafe and secretive methods of abortion.34 Adding to this cycle, healthcare providers perpetuate stigma through their discriminatory actions and refusal to offer essential services.8, 30 Women encounter multilayered stigma originating from communities and the healthcare system.23, 24 Addressing stigma requires comprehensive strategies that span sociocultural, legal, health systems, and geographic spheres. Increased awareness, community engagement, improved provider training, and more robust legal frameworks can slowly transform social attitudes and norms.7, 24, 25, 33 Including parents in communicating about SRH with adolescents fosters supportive family environments.23 Adolescent-friendly healthcare services meet the needs of young women by providing a welcoming space for information and care.23 Confidential, nonjudgmental care from trained staff mitigates stigma and makes women more likely to seek timely, appropriate care.32 Positive attitudes among healthcare staff toward abortion laws create an atmosphere of empathy and understanding that encourages care-seeking.26

4.3 Geographic and accessibility factors

Nepal's diverse terrain creates geographic barriers that, along with economic and social factors, challenge access to SAS and underscore disparities.8, 9, 25, 32 Rural areas suffer from scarce facilities and trained providers, obstructing services.8, 9, 25, 32 Rugged topography poses transportation obstacles, with remote regions especially affected.30, 33 Many women struggle to afford travel and clinic fees, creating financial barriers.8, 34 Rural populations have limited access to SAS availability in general.7, 24 High private clinic costs further constrain the affordability.7, 23-25, 30, 33 These intertwined geographic, economic, and social barriers hinder timely and appropriate care.

However, some facilitators show promise in improving access. Reducing service costs alleviates financial limitations.24 Expanding availability beyond cities helps address geographic disparities in rural areas.7, 24 Leveraging local auxiliary nurses, midwives, and volunteers facilitates community-level care.33

4.4 Healthcare system factors

Numerous barriers within Nepal's healthcare system obstruct the provision of SAS, requiring careful attention to pave the way for improved accessibility and quality.7, 8, 22, 25, 30, 33-35, 38 A major challenge is the lack of knowledge about abortion and available services among women.8, 33 Being uninformed hinders their ability to make appropriate decisions, potentially delaying care or leading to unsafe practices. The shortage of trained healthcare providers equipped to offer SAS results in inadequate counseling and care.34 The absence of a safe and confidential environment can deter women from seeking SAS, perpetuating unsafe abortions.7, 23, 37 The scarcity of trained providers and facilities, especially in certain regions, forces women to endure logistical hurdles to access care far from home.8, 30, 38 This underscores the urgency of expanding the reach of services to remote areas. Failure to provide effective postabortion contraception contributes to repeat unintended pregnancies and unsafe practices.34 The provision of inaccurate information and unsafe medications provided by untrained pharmacy staff further endangers women's health and lacks a proper referral system.26, 35

Despite these challenges, numerous facilitators show promise in improving SAS in Nepal. Providing women with comprehensive counseling and information promotes informed choices and timely, safe care.24 Training female CHV to offer referrals bridges the access gap, particularly in rural areas.28 Widening availability of medical abortion pills enables convenient, safe termination of early pregnancies.25, 33, 38 Pharmacies can serve as accessible points to obtain these medications privately.9, 33, 35 Training non-clinicians in abortion care enhance access in underserved regions.29, 33, 35 Expanding the number of trained providers and facilities ensures that the services are within reach for more women.7, 25 Referral networks prevent denial of care and resorting to unsafe means.29 Fostering confidential, nonjudgmental settings encourages care-seeking.7, 24 Reducing stigma creates a supportive environment.7 Collaborations with organizations provide resources to strengthen SAS delivery.25 Training mid-level health providers such as ANM brings care closer to the communities.31 Ongoing monitoring and evaluation maintain quality and equity.9

4.5 Strengths and limitations

This review has both strengths and limitations. A major strength is the comprehensive search across multiple databases and gray literature, providing a solid foundation of evidence. The included studies utilized sound methodologies, including surveys, interviews, and record reviews. However, the quality and depth of evidence varied. Some barriers/facilitators were only supported by a few studies, indicating a need for more research in those areas. Many studies relied on self-reported data, which could introduce bias. Most of the evidence came from cross-sectional studies, limiting the ability to infer causality between barriers/facilitators and access outcomes. There was minimal data directly linking identified factors to abortion morbidity/mortality. Few studies evaluated interventions or policies to improve access. While valuable insights emerged, higher-quality longitudinal and interventional studies are required to strengthen the knowledge base on improving the safe provision of abortion in Nepal.

5 CONCLUSION

The review identified and analyzed various barriers and facilitators to ensuring wider accessibility to SAS. The major barriers identified were financial constraints, unfavorable geography, lack of infrastructure, and fear of social stigmatization. The main factors favorable for abortion services were economics and geography. Legalization of abortion reinforced with improved access to abortion services in rural areas, reduced cost and the active involvement of ANM and CHV have played crucial roles in facilitating abortion services.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Alok Atreya: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Kishor Adhikari: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Samata Nepal: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing—review and editing. Milan Bhusal: Writing—original draft. Ritesh G. Menezes: Methodology; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing. Dhan B. Shrestha: Project administration, resources, writing—review and editing. Deepak Shrestha: Writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Alok Atreya affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Our study did not generate any unique datasets or data files. All data used in this research are either publicly available in the manuscript or can be obtained through the referenced sources.