Gastrointestinal symptoms among COVID-19 patients presenting to a primary health care center of Nepal: A cross-sectional study

Abstract

Background and Aim

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a major public health problem causing significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Apart from respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort are quite common among COVID-19 patients. The gastrointestinal tract can be a potential site for virus replication and feces a source of transmission. Thus, ignorance of enteric symptoms can hinder effective disease control. The objective of this study is to see the gastrointestinal manifestation of the disease and its effect on morbidity and mortality.

Methods

This observational cross-sectional retrospective study was carried out among 165 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients in primary health care of Gorkha, Nepal from March 1, 2021 to March 1, 2022. A systematic random sampling method was adopted while data were entered and analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21.

Results

Of 165 patients, 97 patients (58.78%) had enteric involvement. Among gastrointestinal symptoms, diarrhea in 67 patients (40.6%) and nausea and/or vomiting in 66 patients (40%) were the most common symptoms, followed by abdominal pain in 27 patients (16.4%) and anorexia in 19 patients (11.5%). Of the majority of cases with gastrointestinal involvement, 63 (63%) were below 50 years of age. Many of the patients who received vaccination had gastrointestinal symptoms (79%). Complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock, and arrhythmia developed in 9.7% of patients, with the death of eight patients. COVID-19 vaccination was associated with 4.32 times higher odds of having gastrointestinal involvement in subsequent COVID-19 infection.

Conclusions

Diarrhea followed by nausea/vomiting was among the most common gastrointestinal symptoms affecting younger age groups in our study. Enteric symptoms were more common among vaccinated people rather than among nonvaccinated ones.

1 INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged as a major challenge to public health globally, causing significant mortality and morbidity. The total number of cases and deaths in Nepal was 702,933 and 8931, respectively, during our study. SARS-CoV-2 is the third coronavirus identified to cause severe respiratory illness in humans, after SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. The most common symptoms in COVID-19 patients are fever, dry cough, myalgia, and shortness of breath (SOB).1, 2 Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort were also common during the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Some individuals developed these symptoms without any respiratory involvement. Gastric infection increases the risk of peptic ulcer in cirrhotic patients by 2.7-fold, and this group of patients sometimes has more GI symptoms.3-5 GI symptoms sometimes preceded respiratory symptoms and were seen in 20%–50% of patients.6

SARS-CoV-2 is found to infect the host tissue by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in respiratory epithelial cells, which are also found in the kidneys and GI tract, particularly small intestinal epithelial cells.7-10 As a result, virus transmission occurs through feces and urine, and the GI system and kidneys may serve as possible extrapulmonary sites for virus replication.10, 11 The virus can be eliminated through the urine and fecal routes and can remain alive for a prolonged time even after the throat swab turns negative; thus, there could be a fecal–oral route of transmission, particularly in areas with improper hygiene and a lack of healthier sanitation practices.4, 9

Studies have reported that the duration of hospital stay and mortality in patients with respiratory and GI symptoms are higher than in those with respiratory symptoms alone.12 However, a study by Livanos et al. showed some reduction in mortality among patients with GI involvement. It was believed to be due to reduced inflammatory mediators, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-17A, C–X–C chemokine 8, and chemokine C–C ligand 8, following GI involvement.13, 14 Hence, we are conducting this descriptive cross-sectional study to see the GI manifestations of the disease and its effect on morbidity and mortality.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Study design and participants

In this observational cross-sectional retrospective, single-center study, we reviewed the record of 165 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients including age, sex, comorbidities, signs and symptoms at presentation, chest X-ray findings, and COVID-19 vaccination status presenting to Aruchanaute primary health care center (PHC) located in a remote region of Gorkha district, Nepal from March 1, 2021 to March 1, 2022. The laboratory-confirmed cases of age more than 18 years with pharyngeal swab specimen test results positive using real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 and with complete information in the record were included in our study. Cases less than the age of 18 years and with incomplete information were excluded from our study. A systematic random sampling method was adopted.

Semistructured questionnaire (proforma) prepared by the investigators themselves through a rigorous literature review was used as a data collection tool. All the required information was filled in by seeing the health records of each subject. Variables of our study were age, sex, comorbidities, signs, and symptoms at presentation. (For full-length questionnaire, see Supporting Information: File 1.)

2.2 Sample size

The sample size was calculated with standard Cochran's sample size formula taking the prevalence of GI symptoms at 12% based on the study by Sravanthi Parasa et al. and 4.96% absolute precision at 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5% significance level.15

The calculated sample size was 165 considering the level of confidence as 95% with a 5% margin of error.

2.3 Research ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol and approved by the ethical review board of the Nepal Health Research Council; protocol registration number: 152/2022P; submitted date: March 28, 2022.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were entered into and analyzed using IBM SPSS® v21 (IBM). Descriptive statistics like frequency, percentages, mean ± SD, and/or median (minimum–maximum) were calculated wherever required and depicted accordingly in bar diagrams. The association of the GI involvements with selected background characteristics was assessed using the χ2 test and binary logistic regression. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The 95% CI of prevalence was estimated using OpenEpi® v3.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline characteristics of the symptomatic and rRT-PCR-positive COVID-19 participants

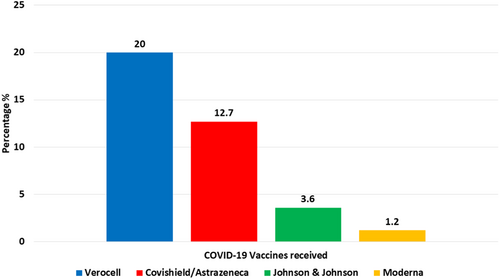

A total of 165 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection were included in our study. Out of 165 cases, 86 (52.1%) were male and 79 (47.9%) were female. The mean age of the patients was 45.02 ± 15.82 (mean ± SD) with a range of 18–83 years (Table 1). Only 22 patients (13.3%) had comorbidities; among these, the majority of patients suffered from hypertension (7.3%), followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4.8%), diabetes mellitus (2.4%), and others (1.2%) (Figure 1). On COVID-19 vaccination status, only 62 patients (37.6%) were vaccinated against COVID-19, with the majority by Verocell at 20%, followed by Covishield/AstraZeneca at 12.7%, Johnson & Johnson at 3.6%, and Moderna at 1.2% (Figure 2).

| Frequency | % | Mean ± SD [median (min–max)] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.02 ± 15.81 [43 (18-83)] | ||

| <50 | 100 | 60.6 | |

| ≥50 | 65 | 39.4 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 86 | 52.1 | |

| Female | 79 | 47.9 | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| No | 143 | 86.7 | |

| Yes | 22 | 13.3 | |

| COVID-19 vaccines received | |||

| No | 103 | 62.4 | |

| Yes | 62 | 37.6 |

- Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; min, minimum; max, maximum; rRT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription PCR.

3.2 Proportion of enteric involvement

Our study found that more than half of the patients confirmed with COVID-19 infection had enteric involvement in 97/165 patients (58.78%). Among GI symptoms, diarrhea in 67 patients (40.6%) and nausea and/or vomiting in 66 patients (40%) were the most common symptoms, followed by anorexia in 19 patients (11.5%) and abdominal pain in 27 patients (16.4%) (Table 2). Among non-GI symptoms, cough was present in majority of patients 124 (75.2%), followed by fever in 118 (71.5%), SOB in 84 (50.9%), fatigue in 76 (46.1%), chest pain in 59 (35.8%), other nonspecific symptoms in 50 (30.3%) and palpitation in 4 patients (2.4%).

| Variables | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 97) | ||

| Diarrhea | 67 | 40.6 |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 66 | 40.0 |

| Anorexia | 19 | 11.5 |

| Pain abdomen | 27 | 16.4 |

| Nongastrointestinal symptoms (n = 159) | ||

| SOB | 84 | 50.9 |

| Sore throat | 79 | 47.9 |

| Chest pain | 59 | 35.8 |

| Cough | 124 | 75.2 |

| Palpitation | 4 | 2.4 |

| Fatigue | 76 | 46.1 |

| Fever | 118 | 71.5 |

| Others nonspecific | 50 | 30.3 |

- Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; rRT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription PCR; SOB, shortness of breath.

3.3 Imaging, treatment, complications, and mortality in COVID-19 cases

Nearly two-fifths of the patients, 70 (42.4%), developed consolidation in a chest X-ray. Sixty-one out of 165 patients (37%) required supportive oxygen, of these 16 patients (26.2%) needed mechanical ventilation. Treatment with steroids was given to 73 patients (44.2%). The duration of stay in the PHC was 6.69 ± 2.90 [7.0 (0–15)] days {mean ± SD [median (min–max)]}. Complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), shock, and arrhythmia developed in 16 patients (9.7%), with the death of eight patients (4.8%) (Table 3).

| Variables | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Chest X-ray consolidation | ||

| No | 95 | 57.6 |

| Yes | 70 | 42.4 |

| Treatment with steroids | ||

| No | 92 | 55.8 |

| Yes | 73 | 44.2 |

| Supportive oxygen | ||

| No | 104 | 63.0 |

| Yes | 61 | 37.0 |

| Means of oxygen therapya | ||

| Nasal cannula | 38 | 62.3 |

| Face mask | 23 | 37.7 |

| Need for mechanical ventilation | ||

| No | 149 | 90.3 |

| Yes | 16 | 9.7 |

| Duration of stay (days) | ||

| Mean ± SD [median (min–max)] | 6.69 ± 2.90 [7.0 (0–15)] | |

| Complicationsb | ||

| No | 149 | 90.3 |

| Yes | 16 | 9.7 |

| Mortality | ||

| No | 157 | 95.2 |

| Yes | 8 | 4.8 |

- Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; min, minimum; max, maximum; rRT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription PCR.

- a Out of those who received oxygen therapy (n = 61).

- b Complications: ARDS, shock, and arrhythmia.

3.4 Association of GI involvement with baseline characteristics

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed among variables like age, gender, comorbidities, and COVID-19 vaccination status with GI involvement. Receiving COVID-19 vaccination was associated with 4.32 times higher odds of having GI involvement in subsequent COVID-19 infection (95% CI, 2.09–8.91; p ≤ 0.001; Table 4).

| Variables | N (%) | GI involvement | % | Binary logistic regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |||

| Age (years) | 0.173 | ||||||

| <50 | 37 | 37.0 | 63 | 63.0 | 1 (ref.) | ||

| ≥50 | 31 | 47.7 | 34 | 52.3 | 0.64 | 0.34–1.21 | |

| Gender | 0.889 | ||||||

| Male | 35 | 40.7 | 51 | 59.3 | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Female | 33 | 41.8 | 46 | 58.2 | 0.96 | 0.51–1.78 | |

| Comorbidities | 0.975 | ||||||

| No | 59 | 41.3 | 84 | 58.7 | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 9 | 40.9 | 13 | 59.1 | 1.02 | 0.41–2.53 | |

| COVID-19 vaccines received | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 55 | 53.4 | 48 | 46.6 | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 13 | 21.0 | 49 | 79.0 | 4.32 | 2.09–8.91 | |

- Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GI, gastrointestinal; ref., reference; rRT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription PCR.

4 DISCUSSION

Early studies from 2019 and 2020 have shown that the proportion of COVID-19 patients presenting with enteric symptoms was low. However, with time and more studies, evidence of enteric involvement was increasing, and GI symptoms were common in patients with COVID-19. Shreds of evidence of feco-oral transmission of COVID-19 are also on the rise.11, 15, 16 The importance of understanding the various organs and systems involved in COVID-19 is unparalleled. Still, there have been very few studies in Nepal reporting such issues. Thus, we aimed to study how COVID-19 had affected the enteric system in COVID-19 patients presenting to a PHC in Nepal.

In this single-center, cross-sectional study, we found that more than half of the patients had at least one GI symptom on presentation. The prevalence of GI symptoms in our study group appears to be comparable with those noted in prior studies.17-22 However, many studies reported GI symptoms in less than 30% of patients infected with COVID-19, ranging from 12.1% to 29.9%.23-29 A higher prevalence of GI symptoms could be due to the tendency to admit as many RT-PCR-positive patients as possible in our study center to isolate and prevent the spread of infection during the study period.

Among GI complaints, diarrhea was the most common complaint that was reported in 40.6% of our patients, followed by nausea/vomiting in 40%. Similar findings have been reported in different parts of the world by different investigators.19, 20, 23-25 However, a meta-analysis conducted by Dong et al.20 reported anorexia at 17% as the most common symptom in COVID-19 patients, followed by diarrhea at 8%, nausea, and vomiting at 7%, and abdominal pain at 3%. Studies done in Arab and Turkish countries reported similar incidences of GI symptoms as reported by Dong and co-workers.20, 21, 28 Abbasinia et al. reported anorexia as the most common complaint of presentation to GI clinics and noted increased GI manifestations in a later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic than in the early stage.30

Infection and inflammation of intestinal epithelial cells by SARS-CoV-2 through ACE2 receptors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of GI symptoms. With the severity of the disease, there is an increase in total leukocyte count and absolute neutrophil count while there is a decrease in absolute lymphocyte count, eosinophils, basophils, hemoglobin, and platelets count.31, 32 Likewise, serum levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP) were also increased and CRP could be used as an indicator of progression and severity of COVID-19 infection.33 The fecal shedding of viral RNA for a prolonged duration, even up to 4 months (12.7%), would explain the prolonged morbidity of COVID-19 infection with GI involvement.16, 34

The younger population (age <50 years) had more GI symptoms than the elderly population (63% vs. 52%) in our study. Our findings were similar to those reported by Leal et al.25 and Bukum et al.21 GI involvement in both males and females was found to be nearly equal (58% vs. 59%) in our study. Dolu et al. reported similar GI involvement in both sexes.27 In contrast, Han et al. (65.7% vs. 51.1%) and Montazeri et al. (28% vs. 23%) reported more GI involvement in females than males.26, 35

A prospective study in India stated more frequent GI symptoms in severe COVID-19 patients with comorbidities than in patients without comorbidities (34.18% vs. 23.68%).36 In contrast, an equal prevalence of GI symptoms in COVID-19 patients with or without comorbidities was noted in our study. This disparity might be due to the fact that severe COVID-19 patients have usually already been treated with antivirals. In our study, COVID-19 patients with vaccinated status had a 4.32-fold higher risk of having GI symptoms than those without vaccination. This is quite an interesting finding of our study, which needs further confirmation and study.

A total of 42.4% of patients with COVID-19 infection had consolidation in the chest radiograph at the time of diagnosis or sometime during the disease course in our study, which is comparable to the findings reported by Sadiq et al. (30 of 64; 47%) and Wong et al. (28%, 95% CI: 8–54).37, 38 Ground-glass opacities were the second most common abnormalities reported in COVID-19-infected patients (10%–53%), contrary to the fact that pleural effusion and pneumothorax were rare findings.38

Mechanical ventilation was done in 16 (9.7%) patients in our study. This rate of mechanical ventilation is similar to that of the study by Dolu et al.27 (9.9%) but less than that of the study by Montazeri et al.26 (16.7%). Our study reported a mortality rate of 4.8%, which was less than that of studies in China and Turkey.1, 27 Schettino et al.17 and Livanos et al.13 found a lower mortality rate in COVID-19 patients with GI symptoms, which is quite controversial as another study conducted in Wuhan reported more mortality in patients with GI symptoms along with respiratory symptoms.12 A study in the United States by Song et al. suggested that patients with isolated GI symptoms without extra GI symptoms had significantly higher mortality rates and higher intensive care unit requirements.39 ARDS, shock, and arrhythmia were the common causes of mortality in our study.

The mean hospital stays of the patients, regardless of GI involvement, in our study were 6.69 ± 2.9 days. Similar hospital durations were reported by Montazeri et al. 26 at 6.03 days and by Leal et al.25 at 7 days. On the contrary, the hospital stay of patients was longer in an American study (13.5 days).19

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study carried out in Nepal to assess the GI involvement of COVID-19 infection. Insights into GI symptoms as presenting complaints of COVID-19 infection help in reaching an early diagnosis and taking measures to control transmission in future outbreaks or pandemics. However, the retrospective design, single primary care center study site, and small sample size are the major limiting factors of this study. Also, similar side effects may occur in persons using antivirals and other medications. As a result, it can be challenging to distinguish between symptoms brought on by viruses and those brought on by drugs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Acute GI symptoms were highly prevalent in COVID-19 patients in our study. Diarrhea and nausea/vomiting were the most common GI symptoms affecting younger patients more than older patients. COVID-vaccinated patients were more likely to have enteric symptoms than nonvaccinated patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shekhar Gurung: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; writing—review and editing. Saurab Karki: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Bishnu Deep Pathak: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology. Gopal K. Yadav: Conceptualization. Gaurab Bhatta: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology. Sumin Thapa: Methodology. Sabin Banmala: Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. Anil J. Thapa: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Kumar Roka: Writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants and research assistants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council Board. The consent was taken in written format, all the patient's details were kept confidential, and no information revealing the patient's identity was disclosed in the article.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Saurab Karki affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The complete data of this research is fully available on request made to the corresponding author.