Social determinants and participation in fecal occult blood test based colorectal cancer screening: A qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis

Abstract

Issue Addressed

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening through fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) has saved thousands of lives globally with multiple countries adopting comprehensive population wide screening programs. Participation rates in FOBT based CRC screening for the socially and economically disadvantaged remains low. The aim of this systematic review is to explore empirical evidence that will guide targeted interventions to improve participation rates within priority populations.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cinahl and PsycInfo were systematically searched from inception to 22 June 2022. Eligible studies contained qualitative evidence identifying barriers to FOBT based CRC screening for populations impacted by the social determinants of health. An inductive thematic synthesis approach was applied using grounded theory methodology, to explore descriptive themes and interpret these into higher order analytical constructs and theories.

Results

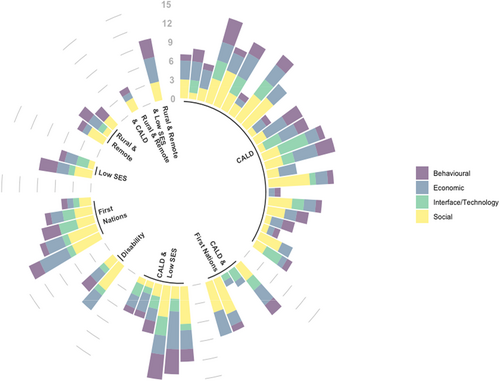

A total of 8,501 publications were identified and screened. A total of 48 studies from 10 countries were eligible for inclusion, representing 2,232 subjects. Coding within included studies resulted in 30 key descriptive themes with a thematic frequency greater than 10%. Coded themes applied to four overarching, interconnected barriers driving inequality for priority populations: social, behavioural, economic and technical/interfaces.

So What?

This study has highlighted the need for stronger patient/provider relationships to mitigate barriers to FOBT screening participation for diverse groups. Findings can assist health professionals and policy makers address the systemic exclusion of priority populations in cancer screening by moving beyond the responsibility of the individual to a focus on addressing the information asymmetry driving low value perceptions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed forms of cancer around the world and contributes significantly to the global burden of cancer, with 1.8 million cases and 896 000 deaths recorded annually.1 Growing rates of CRC have been identified in many developed countries with rates predicted to increase 60% by 2030, placing CRC prevention as a key priority for many governments around the world.2

The application of a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) in targeting population-wide detection of CRC, has proven to be an efficacious means of achieving significant reductions in mortality rates.3 While methods for collection can differ between tests, screening through FOBT typically involves taking a small sample of stool and testing it for ‘hidden blood’. Blood in the stool can be indicative of abnormalities, suggesting the need for further clinical investigation. The process is both highly sensitive and highly specific in its ability to screen for cancerous and precancerous abnormalities in the large bowel or colon.4 The growing burden of CRC has been addressed by a number of nations through population-wide screening while other countries use FOBT as one of many opportunistic modalities to screen for CRC.5 CRC screening through FOBT has achieved global success in reducing CRC morbidity and mortality, however successful screening outcomes are reportedly less prevalent for socially and economically disadvantaged groups, where data are available.

The World Health Organisation describes health inequities faced by communities impacted by the social determinants of health, as avoidable inequalities driven by social and economic conditions that determine a person's risk of illness.6 Trends in CRC screening participation frequently demonstrates strong correlation between the social determinants of health and those populations groups experiencing disadvantage in their ability to access screening at the same rate as the general population.7

Groups which have been identified as having an unequal share or a lower rate of access to health resources, include populations belonging to the following groups: culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD), disability, Indigenous peoples, low socio-economic status (SES), and rural and remote. In addition to the frequently cited minority populations noted as being a priority, we also included lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex+ (LGBTQI+) communities which are often discounted due to lack of evidence, low medical identification or misrepresentation in medical reporting and who historically are impacted by low access to health services, low health seeking behaviour and poorer health outcomes.8

Several studies have published synthesised data relating to barriers to participation in CRC screening for both the general population and priority groups. A range of barriers preventing participation in FOBT screening among groups have been identified, however none have focused specifically on FOBT as a screening modality for CRC and the empirical evidence pertaining to all socially and economically disadvantaged groups both individually and as a whole.9

Against this background, the aim of this systematic review is to integrate the findings of all qualitative evidence relating to barriers to participation in FOBT CRC for priority populations. We aimed to analyse the perspectives, attitudes and beliefs contributing as barriers to positive health behaviours for diverse groups, creating new insights and understanding into the drivers of inequality in access to FOBT CRC screening.

2 METHODS

This systematic review has been conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA), guidelines and Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines and utilises a methodologically rigorous qualitative meta-synthesis approach in accordance with Sandelowski and Barroso.10 The protocol has been registered and published on Prospero (CRD42021250636) with no further amendments made.

2.1 Search strategy

The search strategy was developed using a combination of key terms and synonyms for ‘colorectal cancer’, ‘screening’, ‘barriers’, ‘FOBT’, ‘Indigenous’, ‘disability’, ‘culturally diverse’, ‘LGBTQI’, ‘Low SES’ and ‘rural and remote’. Synonyms and spelling variations to represent the differences in specific American and English copy were included. For a full detail of the search strategy, see Supplementary Files. The final search strategy was adapted for Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cinahl, PsycInfo and Cochrane. Grey literature searches were conducted through Scopus, Google advanced search and by using the ‘snowball’ technique of searching bibliography lists of included references.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were identified as eligible in this systematic review if they answered the research question by (a) including one or more of the identified priority populations impacted by the social determinants of health; (b) identifying empirical evidence contributing as a barrier to participation in FOBT CRC Screening; (c) utilising qualitative or mixed methodologies; (d) reporting original data. Articles were excluded from the systematic review if (a) barriers to screening could not be linked directly to patient experiences with FOBT testing; (b) studies did not contain the experiences and perceptions of at least one identified priority population; (c) quantitative study design only; (d) studies that did not include or report original data.

2.3 Data analysis

Studies were imported into Endnote where duplicates were removed before importing into COVIDENCE software for title and abstract screening. Data extraction follows meta-synthesis techniques by extracting findings from qualitative studies that answer the research question. This study objectively followed a 3-step approach involving meta-synthesis techniques to extract data through thematic coding, the development of a taxonomy of findings to demonstrate the conceptual range of data and the rendering of data to form new interpretations and theory. In line with Grounded Theory methodology, thematic coding and the development of new theory were created through the course of data extraction, memo writing and analysis, deriving new meaning and understanding of the phenomenon of equity and access to FOBT CRC screening for disadvantaged communities. In this study, coding has been applied in all instances when a barrier is disclosed by a participant from one of the identified priority populations. In some cases, community leaders' perceptions were included if they identified as belonging to one of the population cohorts under investigation.

2.4 Quality assessment/critical appraisal

Quality appraisal was conducted using the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) where a 10-point check was conducted assessing quality of included qualitative studies using symbols (+/−) to demonstrate adherence to quality reporting of qualitative research. This tool was chosen due to its endorsement from the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group and due to the objective nature of appraisal. Two independent reviewers conducted the appraisal process with consensus reached on any variations in recorded assessment of study content.

2.5 Data extraction

Data extraction was coded inductively, line by line using NVIVO 12 PLUS Software. Two independent reviewers coded and cross-checked references for thematic relevance. During the initial phase of coding, memo writing was adopted to demonstrate the interconnectedness of themes and the thematical relevance and repetition among priority populations. During the second round of coding, thematic relevance was re-examined and cross-checked to ensure coded descriptive themes were conceptually ordered, representing distinguishable data. Codes were then grouped into higher order themes representing the key emergent findings from the cohort of included studies. When data were reported from mixed populations, clear identification of a priority population of interest had to be present with each statement for coding to be applied.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Search results

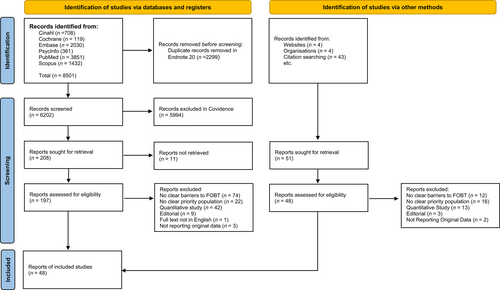

The search identified 8501 papers of which 2299 duplicate papers were removed using EndNote 20 software. The remaining 6202 papers were imported into COVIDENCE for Title and Abstract screening based on the selection criteria. Two independent reviewers screened articles for relevance with all discrepancies resolved by mutual discussion. Abstracts were eliminated in the initial screening if they used a quantitative only research design and did not report findings representing one or more of the identified priority populations. Full text of the remaining 197 papers were retrieved and reviewed against the full inclusion/exclusion criteria using the COVIDENCE voting system. Disagreements over the final study inclusions were resolved by a third-party neutral arbitrator. A total of 48 papers were included in this review of the literature. A flow chart of the study selection process is reported in Figure 1.11-58

The basic characteristics extracted from the 48 included studies are presented in Table 1. Data on year of publication, country, aim, qualitative methodology, priority population and priority population sample size were all extracted using a customised Excel template. A total of 2232 subjects expressed barriers to FOBT based screening were included in the 48 studies across 10 countries. Population representation of included studies covered CALD (n = 32), Indigenous peoples (n = 6), disability (n = 2), Low SES (n = 3), rural/remote (n = 5) and LGBTQI+ (n = 0). Focus groups were the key method used to collect data and represented 52% of included studies, followed by a variety of semi-structured, in-depth and face to face interview formats.

| Authors | Title | Publication year | Country | Qualitative methodology | Aim or objective | Priority population | Priority population sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguado et al.12 | Simple and easy:’ providers’ and Latinos’ perceptions of the faecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colorectal cancer screening. | 2020 | USA | Focus groups | To explore the knowledge and awareness of FOBT testing amongst Latinos. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 49 |

| Angus et al.13 | Access to cancer screening for women with mobility disabilities. | 2011 | Canada | Focus group | To explore the experiences women with disabilities face when accessing cancer screening services. | Disability | 24 |

| Bachman et al.14 | Identifying communication barriers to colorectal cancer screening adherence among Appalachian Kentuckians. | 2018 | USA | In depth interviews | To explore the communication needs and patient perspectives that would contribute to improved CRC screening for rural/remote and low sees people. | Rural/remote | 40 |

| Bass et al.15 | Perceptions of colorectal cancer screening in urban African American clinic patients: differences by gender and screening status. | 2011 | USA | Focus groups | To explore how perceived barriers to CRC screening impact screening status amongst African Americans | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 23 |

| Bastani et al.16 | Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among ethnically diverse high- and average-risk individuals. | 2001 | USA | Focus group | To explore perceptions surrounding barriers to screening for high-risk individuals from culturally and economically diverse backgrounds. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 56 |

| Brouse et al.17 | Barriers to colorectal cancer screening with faecal occult blood testing in a predominantly minority urban population: A qualitative study. | 2001 | USA | Telephone interviews | To identify barriers to FOBT screening among low income, minority populations. | Culturally and linguistically diverse AND low socio-economic status (coded to CALD) | 8 |

| Busch et al.18 | Elderly African American women's knowledge and belief about colorectal cancer. | 2003 | USA | Focus groups | To assess African American Women's knowledge and awareness of CRC and to assess the degree in which they seek preventative measures for CRC. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 13 |

| Byrd et al.19 | Barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening within a Hispanic population. | 2019 | USA | Focus group | To explore knowledge, attitudes and beliefs on CRC screening and preferences for FOBT screening among Texan based Hispanics. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 56 |

| Choe et al.20 | ‘Heat in their intestine’: colorectal cancer prevention beliefs among older Chinese Americans. | 2006 | USA | Semi structured interviews | To explore the beliefs and behaviours impacting croc screening among Chinese Americans | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 30 |

| Colón-López et al.21 | Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about colorectal cancer screening in Puerto Rico. | 2022 | Puerto Rico | Focus groups | To determine the key factors influencing participation in colorectal cancer screening for Puerto Rican men and women. | Rural/remote and low socio-economic status (coded rural/remote) | 51 |

| Coronado et al.22 | Reasons for non-response to a direct-mailed FIT kit program: lessons learned from a pragmatic colorectal-cancer screening study in a federally sponsored health centre. | 2015 | USA | Phone interviews | To explore factors acting as barriers to FOBT screening among Spanish speaking people. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 11 |

| Crawford et al.23 | Colorectal cancer screening behaviours among south Asian immigrants in Canada: An exploratory mixed methods study. | 2015 | Canada | Focus groups | To discover an in-depth understanding of CRC beliefs among South Asian immigrants. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 42 |

| Daley et al.24 | American Indian community leader and provider views of needs and barriers to colorectal cancer screening. | 2012 | USA | Interviews | To identify barriers to CRC screening for American Indians to increase future screening. | First Nations | 13 |

| Dharni et al.25 | Factors influencing participation in colorectal cancer screening-a qualitative study in an ethnic and socio-economically diverse inner city population. | 2017 | England | Face to face interviews | To explore the factors contributing to the inequalities in croc screening for ethnically and socially diverse communities. | Culturally and linguistically diverse AND low socio-economic status (coded to CALD) | 30 (Participants confirmed from CALD backgrounds. Low SES were not split between CALD and White British so cannot be recorded. |

| Fernandez et al.26 | Colorectal cancer screening among Latinos from U.S. cities along the Texas-Mexico border. | 2008 | USA | Focus groups | To explore the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and emotions of Latinos in regards to CRC screening. | Culturally and linguistically diverse AND low socio-economic status (coded to CALD) | 92 |

| Filippi et al.27 | American Indian perceptions of colorectal cancer screening: viewpoints from adults under age 50. | 2013 | USA | Focus group | To identify barrier to screening for American Indian populations to assist culturally sensitive strategy development to increase participation. | First Nations | 70 |

| Filippi et al.28 | Views, barriers, and suggestions for colorectal cancer screening among American Indian women older than 50 years in the Midwest. | 2012 | USA | Focus groups | To investigate the perceptions of rescreening and barriers to screening amongst American Indian women. | First Nations | 52 |

| Goodman et al.29 | Barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among Mid-Atlantic Latinos: focus group findings. | 2020 | USA | Focus group | To explore barriers and enablers to CRC screening among Mid Atlantic Latinos. | Culturally and linguistically diverse AND low socio-economic status (coded to CALD) | 70 |

| Harden et al.30 | Exploring perceptions of colorectal cancer and faecal immunochemical testing among African Americans in a North Carolina community. | 2011 | USA | Focus groups | To discover knowledge, understanding and beliefs of CRC screening among low income African Americans. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 28 |

| Hoeck et al.31 | Barriers and facilitators to participate in the colorectal cancer screening programme in Flanders (Belgium): a focus group study. | 2020 | Belgium | Focus group | To identify barriers and facilitators to CRC screening for non-participating Belgium's. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 23 |

| Holmes-Rovner et al.35 | Colorectal cancer screening barriers in persons with low income. | 2002 | USA | Focus groups | To provide insight into barriers to CRC amongst underserved and vulnerable populations. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 10 |

| Javanparast et al.32 | Barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in different population subgroups in Adelaide, South Australia. | 2012 | Australia | Interviews | To explore barriers and enablers of CRC screening amongst diverse communities. | Culturally and linguistically diverse & first nations (coded to CALD category) | 94 |

| Lu et al.34 | Is colorectal cancer a Western disease? Role of knowledge and influence of misconception on colorectal cancer screening among Chinese and Korean Americans: a mixed methods study. | 2016 | USA | Focus groups | To better understand the relationship between CRC knowledge and misconceptions contributing to low CRC screening amongst Chinese and Korean Americans | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 120 |

| McGraw et al.36 | Tough but not terrific: value destruction in men's health. | 2021 | Australia | Semi structured focus group interviews | To investigate the role of masculine identity and the impact it has on participating in CRC screening. | Rural/remote | 8 |

| Molina-Barceló et al.37 | To participate or not? Giving voice to gender and socio-economic differences in colorectal cancer screening programmes. | 2011 | Spain | Focus groups | To analyse the difference in knowledge and barriers to CRC screening among gender and socio economic diverse groups. | Low socio-economic status | 32 |

| Natale-Pereira et al.38 | Barriers and facilitators for colorectal cancer screening practices in the Latino community: perspectives from community leaders. | 2008 | USA | Focus group | To identify the barriers and enablers impacting CRC screening participation rates amongst Latinos in America. | Culturally and linguistically diverse AND low socio-economic status (coded to CALD) | 36 |

| Ogedegbe et al.40 | Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cancer early detection among low-income minority women in community health centres. | 2005 | USA | Interviews | To explore perceptions, barriers and enablers of cancer screening among low income women. | Low socio-economic status | 187 |

| Oh et al.41 | A qualitative analysis of barriers to colorectal cancer screening among Korean Americans. | 2021 | USA | Focus groups | To better understand the knowledge, attitudes and CRC screening practices among Korean Americans. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 51 |

| Palmer et al.42 | Colorectal cancer screening preferences among African Americans: which screening test is preferred? | USA | In depth interviews | To explore perceptions and preferences on different CRC screening modalities. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 60 | |

| Palmer et al.43 | Reasons for non-uptake and subsequent participation in the NHS bowel cancer screening programme: a qualitative study. | 2014 | England | Focus groups | To explore perceptions on gFOBT and reasons behind non participation for men of African Caribbean origin. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 22 |

| Palmer et al.44 | Understanding low colorectal cancer screening uptake in South Asian faith communities in England—a qualitative study. | 2015 | England | Key informant interviews | To identify reasons contributing to low CRC uptake amongst the South Asian communities in the UK. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 16 |

| Phillipson et al.45 | Factors contributing to low readiness and capacity of culturally diverse participants to use the Australian national bowel screening kit. | 2019 | Australia | Focus groups | To assess the usability of mailed FOBT to CALD populations. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 33 |

| Pitama et al.46 | Exploring Maori health worker perspectives on colorectal cancer and screening. | 2012 | New Zealand | Focus groups | To explore Maori health worker perspectives on cancer screening and to identify possible barriers to CRC screening. | First Nations | 30 |

| Sentell et al.47 | Health literacy, health communication challenges, and cancer screening among rural Native Hawaiian and Filipino women. | 2013 | USA | Focus groups | To explore health literacy and cancer screening knowledge for rural living Native Hawaiians and Filipinos. | First Nations and culturally and linguistically diverse (coded to first nations) | 77 |

| Severino et al.48 | Attitudes towards and beliefs about colorectal cancer and screening using the faecal occult blood test within the Italian-Australian community. | 2009 | Australia | Semi structured interviews | To explore factors influencing participation or non participation in iFOBT screening among Italian migrants. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 20 |

| Shokar et al.39 | Cancer and colorectal cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and screening preferences of a diverse patient population. | 2005 | USA | Individual interviews | To explore patient knowledge and beliefs surrounding colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer screening tools. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 20 |

| Siddiq et al.49 | Beyond Resettlement: Sociocultural Factors Influencing Breast and Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Afghan Refugee Women. | 2020 | USA | Semi structured interviews | To explore the socio-cultural factors influencing cancer screening in Afghan Refuge Women. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 19 |

| Smith et al.33 | Evaluation of the bowel screening pilot eligible population perspectives. | 2013 | New Zealand | In depth interviews | To discover perceptions, attitudes and behaviours on CRC screening for non responders in the pilot Bowel Screening Program. | First Nations | 12 |

| Solenberg et al.50 | Barriers to colorectal cancer screening for people with spinal cord injuries and/or disorders: a qualitative study | 2021 | USA | Interviews | To explore knowledge of CRC and barriers to screening for people with spinal cord injuries or disorders. | Disability | 30 |

| Tatari et al.51 | Perceptions about cancer and barriers towards cancer screening among ethnic minority women in a deprived area in Denmark—a qualitative study. | 2020 | Denmark | Interviews. Semi structured focus groups, group interviews and individual interviews. | To explore the perceptions and barriers to cancer screening among minority women in Denmark. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 37 |

| Unger-Saldaña et al.52 | Barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening in a low-income urban community in Mexico City | 2020 | USA | Focus groups and interviews | To discover the perceptions of barriers and facilitators to CRC screening among Hispanics with low socio-economic status. | Low socio-economic status AND culturally and linguistically diverse (coded to LOW SES) | 30 |

| Vilaro et al.11 | A subjective culture approach to cancer prevention: rural black and white adults' perceptions of using virtual health assistants to promote colorectal cancer screening. | 2022 | USA | Focus groups | To explore and compare CRC perceptions and how they differ between black and white participants living in rural North Florida. | Rural/remote AND culturally and linguistically diverse (coded rural/remote) | 154 |

| Ward et al.55 | Equity of colorectal cancer screening: which groups have inequitable participation and what can we do about it? | 2011 | Australia | In-depth interviews | To discover the factors influencing inequities in CRC participation in Australia. | Culturally and linguistically diverse & first nations (coded to CALD) | 94 |

| Ward et al.54 | Institutional (mis)trust in colorectal cancer screening: a qualitative study with Greek, Iranian, Anglo-Australian and Indigenous groups. | 2015 | Australia | In-depth interviews | To explore perceptions of trust in federally delivered CRC screening programs amongst diverse communities. | Culturally and linguistically diverse & first nations (coded to CALD) | 67 |

| Ward et al.53 | Trust, choice and obligation: a qualitative study of enablers of colorectal cancer screening in South Australia. | 2105 | Australia | In-depth focused interviews | To explore the concept of choice and societal moral obligation in cancer screening among diverse Australian communities. | Culturally and linguistically diverse AND first nations (coded as CALD) | 67 |

| Winterich et al.56 | Men's knowledge and beliefs about colorectal cancer and 3 screenings: education, race, and screening status. | 2011 | USA | In-depth interviews | To explore how demographic factors influence CRC knowledge, attitudes and experiences towards CRC screening. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 35 |

| Woudstra et al.57 | Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding colorectal cancer screening among ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands—a qualitative study. | 2016 | Netherlands | Interviews. semi structured focus groups, group interviews and individual interviews. | To assess the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of CRC screening among ethnic minority groups. | Culturally and linguistically diverse | 30 |

| Zoellner et al.58 | A multilevel approach to understand the context and potential solutions for low colorectal cancer (CRC) screening rates in rural Appalachia clinics. | 2021 | USA | Open ended qualitative interviews | To explore patient level factors influencing participation in CRC screening. | Rural/remote | 60 |

| Total priority population sample | 2232 | ||||||

- Note: In the case of multiple sub populations represented in one study, coding was applied to the priority population with the greatest representation.

3.2 Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal have been detailed in Table 2. Overall, 90% of studies were ranked between 8 and 10 (n = 43) on the CASP tool. The quality of transparent reporting was generally to a high standard, however some studies lacked methodological congruency and rigour of reporting. Reviewers reached agreement on most studies with areas of disagreements resolved through discussion.

| Title | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 10. How valuable is the research? | Overall score out of 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Simple and easy:’ providers’ and Latinos’ perceptions of the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colorectal cancer screening. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Access to cancer screening for women with mobility disabilities. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Identifying communication barriers to colorectal cancer screening adherence among Appalachian Kentuckians. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Perceptions of colorectal cancer screening in urban African American clinic patients: differences by gender and screening status. | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 8 |

| Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among ethnically diverse high- and average-risk individuals. | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 8 |

| Barriers to colorectal cancer screening with fecal occult blood testing in a predominantly minority urban population: a qualitative study. | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | 4 |

| Elderly African American women's knowledge and belief about colorectal cancer. | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | 6 |

| Barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening within a hispanic population. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Heat in their intestine: colorectal cancer prevention beliefs among older Chinese Americans. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about colorectal cancer screening in Puerto Rico. | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 8 |

| Reasons for non-response to a direct-mailed FIT kit program: lessons learned from a pragmatic colorectal-cancer screening study in a federally sponsored health centre. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Colorectal cancer screening behaviours among south Asian immigrants in Canada: an exploratory mixed methods study. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| American Indian community leader and provider views of needs and barriers to colorectal cancer screening. | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| Factors influencing participation in colorectal cancer screening-a qualitative study in an ethnic and socio-economically diverse inner city population. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Colorectal cancer screening among Latinos from U.S. cities along the Texas-Mexico border. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| American Indian perceptions of colorectal cancer screening: viewpoints from adults under age 50. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Views, barriers, and suggestions for colorectal cancer screening among American Indian women older than 50 years in the Midwest. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among Mid-Atlantic Latinos: focus group findings. | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 8 |

| Exploring perceptions of colorectal cancer and fecal immunochemical testing among African Americans in a North Carolina community. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Barriers and facilitators to participate in the colorectal cancer screening programme in Flanders (Belgium): a focus group study. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Colorectal cancer screening barriers in persons with low income | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in different population subgroups in Adelaide, South Australia. | + | + | + | + | + | _ | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Is colorectal cancer a western disease? Role of knowledge and influence of misconception on colorectal cancer screening among Chinese and Korean Americans: a mixed methods study. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Evaluation of the bowel screening pilot eligible population perspectives. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Tough but not terrific: value destruction in men's health. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| To participate or not? Giving voice to gender and socio-economic differences in colorectal cancer screening programmes. | + | + | + | + | − | − | _ | + | + | + | 7 |

| Barriers and facilitators for colorectal cancer screening practices in the latino community: perspectives from community leaders. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cancer early detection among low-income minority women in community health centres. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| A qualitative analysis of barriers to colorectal cancer screening among Korean Americans. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Reasons for non-uptake and subsequent participation in the NHS Bowel cancer screening programme: a qualitative study. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Understanding low colorectal cancer screening uptake in South Asian faith communities in England—a qualitative study. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Colorectal Cancer Screening Preferences Among African Americans: Which Screening Test is Preferred? | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Factors contributing to low readiness and capacity of culturally diverse participants to use the Australian national bowel screening kit. | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| Exploring māori health worker perspectives on colorectal cancer screening. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Health literacy, health communication challenges and cancer screening among rural Native Hawaiians and Filipino Women. | + | + | + | + | + | − | _ | + | + | + | 8 |

| Attitudes towards and beliefs about colorectal cancer and screening using the faecal occult blood test within the Italian Australian community. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Cancer and colorectal cancer: knowledge, beliefs and screening preferences of a diverse patient population. | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | _ | + | + | 7 |

| Beyond resettlement: sociocultural factors influencing breast and colorectal cancer screening among afghan refugee women. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Barriers to colorectal cancer screening for people with spinal cord injuries and/or disorders: a qualitative study. | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | 7 |

| Perceptions about cancer and barriers towards cancer screening among ethnic minority women in a deprived area in Denmark—a qualitative study. | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 8 |

| Barriers and facilitators for colorectal cancer screening in a low-income urban community in Mexico City. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| A subjective culture approach to cancer prevention: rural black and white adults perceptions of using virtual health assistants to promote colorectal cancer screening. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Trust, choice and obligation: a qualitative study of enablers of colorectal cancer screening in South Australia. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Institutional (mis)trust in colorectal cancer screening: a qualitative study of Greek, Iranian, Anglo-Australian and Indigenous groups. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Equity of colorectal cancer screening: which groups have inequitable participation and what can we do about it? | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| Men's knowledge and beliefs about colorectal cancer and three screenings: education, race and screening status. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding colorectal cancer screening among ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands—a qualitative study. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 9 |

| A multilevel approach to understand the context and potential solutions for low colorectal cancer (CRC) screening rates in rural Appalachia clinics. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

3.3 Barriers to FOBT screening

Barriers to FOBT screening fell into 30 key descriptive themes with a thematic frequency greater than 10%. Themes translated further into four overarching, interconnected barriers driving inequality for priority populations: social, behavioural, economic and technology/interface barriers. No study represented data on LGBTQI+ populations specifically, however one disability focused study referenced this group as a population experiencing marginalization and barriers to screening extending beyond normative assumptions surrounding their bodies to presumptions on heteronormative sexuality. Bias and narrow perception on gender identification and sexuality for disabled communities were found to be deeply embedded in society.13 A full taxonomy of findings, including thematic frequencies is displayed in Table 3. Figure 2 continues to depict these frequencies further with one spike representative of each included study and the key barriers identified within each publication.

| Themes | Sub themes | Description | Number of papers theme presents | Frequency of theme coded in Total within studies | Frequency effect size | Outstanding quotes or statements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Social barriers Community level barriers that are linked to circumstances stemming from the social determinants of health and the social elements shaping decision making abilities. |

Taboo to talk about CRC or illness | Taboo to talk about CRC/Fear of becoming ill with cancer if discussing cancer amongst family or friends. | 8 | 14 | 17% | ‘There's not enough going on [in terms of CRC awareness] … I do not know of any [CRC awareness] going on in any schools or talking circles, or any other places, if it's mentioned. Because it's something. It is very private. And there's a lot of fear involved in it’. |

| Belief in traditional healing and medicine | The use of traditional medicines and rituals in place of conventional medicine or the need for navigation through western medicine in collaboration with traditional healing practices. | 7 | 11 | 15% | ‘The other thing is I have a friend … and he's a traditional [Indian] doctor … and I went to him and got doctored for some things, and he sucked up different things in different parts of my body. But one of the things is when he sucked on me and he was counting he said there's six polyps and he sucked them up. He showed them to me. They were just tiny, you know’. | |

| Taboo to talk about CRC or illness | Taboo to talk about CRC/fear of becoming ill with cancer if discussing cancer amongst family or friends. | 8 | 14 | 17% | ‘There's not enough going on [in terms of CRC awareness] … I do not know of any [CRC awareness] going on in any schools or talking circles, or any other places, if it's mentioned. Because it's something. It is very private. And there's a lot of fear involved in it’. | |

| Fatalism of cancer | The belief that health outcomes are predetermined by fate and that there is little or no control of the inevitable. Beliefs and perceptions of ill health causation, often surrounding God/supernatural elements. | 16 | 30 | 33% | ‘I’m glad we have the fullness of the Holy Spirit. I feel confident and strong mentality. I am not worried about getting cancer. 70% or 80% of people diagnosed with cancer will die anyway [even if they get treatment]… I would like to live the rest of my life without being worried [so I do not want screening].’ | |

| Fear of talking about colon or rectum/accessing preventative health services is challenging masculinity | Homophobia, masculinity and concerns about community perceptions. | 6 | 7 | 12% | ‘That male ego and with a touch of, you know, kind of homophobe type thing. You do not want to be perceived… most men do not want to be perceived as, you know, like he said, a softy or somebody that, you know, too obsessed about that orifice in their backside back there’. | |

| Lack of symptoms | The belief that CRC screening was not needed as there were no symptoms or reason to be concerned about CRC. | 17 | 25 | 35% | ‘I’ve never had one, so I do not feel I need one. Nothing's wrong. Because if there are no symptoms and no problems of any type, I can's see just searching in there to have stuff done’. | |

| Belief that GPs withhold important information. | Perception that GPs are withholding information/not including patients in decision making processes or not fully informing them of options. | 7 | 13 | 15% | ‘I heard these doctors, about five or six of them, standing around talking about me. About all the tests they did on me and these charts, I had blood work and everything. And they would mention this and that. But there was never anything that I could nail down specifically. So when my main doctor came in, I asked ‘What was that all about?’ Am I falling apart? And he just said, ‘no, this is something we usually do.’ But I did not have enough information’. | |

| Medical mistrust/ negative experience with HCP | Negative past experiences contributing to general mistrust of GPs and other HCPs. | 15 | 45 | 31% | ‘Specifically, ‘do not trust Indian Health’, is kind of how a lot of us, you know I is not speaking for everybody but I know that's how I feel. If I’m ailing there will be a few days of ailing before I’ll be like, ah, I got nowhere else to go, you know. I better go get in and at least get an idea of what I got’. | |

| Perceived discrimination, bias, racism, marginalisation by HCPs | Perceived lower quality of care, abusive behaviour, racism or inhumane treatment when seeking care from a HCP. | 12 | 25 | 25% | ‘Right now I’m my own advocate. If I want a test now, I have to literally go and beg. The politics I’ve had to play to get tests are ridiculous. When you are disabled, I find you are put on the lowest part of the list.’ | |

| Feeling of disempowerment or inability to self advocate in GP visits | Feeling disempowered in GP visits with a lack of ability to advocate and ask questions | 6 | 12 | 12% | ‘…and a lot of our Māori are frightened to ask questions… so they sit and they hear all these flash words and it can be quite intimidating… they fear that if they ask a question it will be considered a dumb question…So a lot of our people do sit there in a real whakama state [withdrawn] about even, you know, asking simple questions’. | |

| Feeling shame, discomfort, or embarrassment to complete FOBT | The nature of the kit and dealing with faecal matter to complete the kit causing shame, embarrassment or discomfort for participant. | 24 | 47 | 50% | ‘I do not want to participate because you need to go through all this effort to put all that in a bottle and then you need to mail it. What if I forget to put it in the mailbox? Then it will start to smell. And what if someone opens the fridge and finds a bottle with faeces? (Turkish woman, R27) “It was like ‘oh my God they are sending out letters about taking samples of your poo… who would send something like this in the mail to you? This made me feel quite uncomfortable’. | |

| FOBT mistrust/government branded mistrust | Mistrust of government and automated FOBT being mailed out. | 6 | 12 | 12% | ‘When I received it through the post I looked at it and I said “oh, why me, what's wrong?” This is what I think: “What's wrong? Is there something wrong with me and they picked me? Why?’ | |

| Lack of trust in FOBT as an accurate screening method or preference for colonoscopy. | Belief that FOBT is not an accurate way to screen for CRC. Beliefs that colonoscopy is the gold standard and FOBT is inferior. | 11 | 25 | 23% | ‘There's a little postcard they sent out and you can put some stool on the card and send it off and they’ll tell you what they found but I do not think that would be very reliable for someone who's got polyps’. | |

Behavioural barriers Personal beliefs/actions that shape decision making abilities and choices about health on an individual level. |

CRC screening not a priority | CRC prevention/screening not placed as a priority within communities. Greater emphasis on curative than preventing something that has not occurred yet. | 13 | 28 | 27% | ‘We live in a rural area, so it's not a high priority as far…you know, if a person does not get sick to where they cannot work, they typically do not go to the doctor. You know we just do not run…preventative maintenance is not done here’. |

| Unpleasant nature of posting faeces | Aversion to posting faeces in the post | 7 | 13 | 15% | ‘The main reason I did not do anything was for culture reasons. I did not fancy putting my poo in the mail. That was my real reason, because I am Māori. I did not mind if I had to take it somewhere, but actually sticking it in the mailbox, who knows who is going to pick it up. I do not mind having to go to a hospital or lab, but actually putting it in a bottle and putting it in mailbox I did not want to do. It's not the right thing to do, this is sort of a bad thing in our way of thinking. You keep those things tidy and away’. | |

| Only engage in health care if sick | Participants only engaged in health care if sick. | 7 | 11 | 15% | ‘you only went to the doctor if you needed to” and was interpreted to be a lack of preventive orientation in the premigration setting’. | |

| Low self-efficacy | Low confidence/knowledge or ability to complete the FOBT correctly. | 16 | 23 | 33% | ‘Okay, you are going to put 2 [pieces of stool] on it, 1 for the bottom, 1 for the top. Then you are going to smear [them] together. For what?’ (woman, group B). Another participant said, ‘All the processes…Lift the toilet seat. Attach it to fit you. Measuring tissue…You know, it's a lot to do. A lot to do for me’ | |

| Fear | Fear of cancer/locus of control or fear surrounding a possible cancer diagnosis. | 29 | 45 | 60% | ‘I was afraid, for fear of …I threw it away, of course—Me, too—Yes, that's the truth—Me too, I was afraid, nothing else’. | |

Economic barriers Financial and infrastructure barriers that impede a person's ability to act on decisions that will positively impact their health. |

Lack of time in GP consultations/feeling rushed | Feeling rushed in GP visits, limited time for consultation and no time to discuss preventative health like CRC screening. | 7 | 9 | 15% | ‘Even for people who go to the doctor, they many times are not explained how to do things. They just have 3 seconds to be with the doctor and then they give you something and say ‘just do it at home and I’ll see you in the next visit,’ but you have no clue how to do it’. |

| Lack of FOBT/CRC screening information and knowledge | Lack of FOBT/CRC information and knowledge on the preventative nature and importance of FOBT screening. | 44 | 92 | 92% | ‘Well, if they do not know about it, they would not think that they are at risk’. ‘[Participant] is right about that. I agree with this too. They have to be told and then they might think that they are at risk.’ Another added, ‘People also do not pay attention if they do not have any symptoms’. | |

| Lack of perceived risk | Belief that they are at very low risk or no risk of developing CRC cancer. | 11 | 24 | 23% | ‘CRC is something that Western people often get due to their meat-heavy dietary style’. A Chinese participant shared ‘In my case, I do not really like meat. Since my diet is almost vegetal based, I do not thinks I will get CRC’. | |

| Belief cancer cannot be cured/cancer prevention is out of their control | Belief that cancer cannot be cured/prevented and that a cancer diagnosis is a death sentence. | 18 | 28 | 38% | ‘Because how can you prevent it? Changing one's life? It could be, but I am not sure, I am not sure’ (Woman, 70 years). | |

| Lack of GP endorsement | Lack of GP involvement, endorsement and recommendation of FOBT screening. | 18 | 23 | 38% | ‘GP's place, if the reception tells you, or even if the GP tells you, you could be a tremendous help, you know, to say—“Have you had this form? Please do it.” That's all, that's all they need […]It comes through the post, that's the end of it. It's good to just ask them or remind them to do it. You know, just like they remind everyone to take their flu jab.’ | |

| Need for financial support | Unpaid time off work concerns or GP follow up costs | 11 | 15 | 23% | ‘So you never know what it's going to cost you. That's my biggest fear of going to the doctor is they are going to break me, even if I got insurance.’ | |

| Lack of privacy | Lack of privacy in the home or within the community to complete the test) | 6 | 11 | 12% | ‘I think in some Aboriginal communities … you might think ‘that health worker, I do not trust him’ because I know that person, that person will go straight out there and tell everyone.’ | |

Interfaces/technological barriers Technological/system-based barriers that impact the ease of access to health programs/services for various population groups. |

Kit Aesthetics | Look of the kit. | 5 | 7 | 10% | ‘The word cancer and the logo and everything, it does not look friendly …it looks scary and makes me worry … ‘ |

| Lack of cultural support and cultural competency | Barriers associated with lack of cultural competency/respect for cultural diversity resulting in an avoidance of the health care system. | 6 | 12 | 12% | ‘Is this going to be sent to all multicultural people? Why did not the government translate this paper? Some people cannot read it; the first barrier is finding out what this kit is about. [Firstly] we need to get someone to translate this [for us], barrier number one, which will take time …we will have to call people [to help] …so people will just throw it to the side somewhere.’ | |

| Complexity of language on FOBT kit and instructions | Difficulty interpreting the language and instructions on the FOBT kit as a barrier to participation | 17 | 50 | 35% | ‘I read the instructions but it was not easy for me to understand what exactly I should do. They provided a phone number to call if we need help but I needed somebody to help me. I decided to call the phone but I did not feel comfortable.’ | |

| Language barriers with HCPs | Language concordance and medical jargon creates barriers to communication with HCPs about CRC prevention and FOBT participation. | 7 | 11 | 15% | ‘They’re not going to talk to you in a language that you understand. Like up on the wards…and the doctors say, ‘Well, you have got blah blah blah,’ double speak medical jargon, blah blah blah. And I’ve watched the Māori patients and their families, they are, ‘Oh yeah, cool, yeah, that's good.’ As soon as they have gone, I’ll go back and I’ll say, ‘Did you understand that?’ ‘No.’ | |

| Need for additional support to complete the kit. | The need of family, HCP or other support in order to complete the FOBT kit successfully. | 22 | 72 | 46% | ‘You sent one to me, which I was going to do, because I did not understand how to do it, I was trying to bring it to the nurse here, so that she know exactly what to do with it.’ | |

| Effect sizes were calculated by dividing the number of reports containing the findings with the total number of reports included in the review. | ||||||

3.4 Social barriers

Social barriers were defined as community level barriers with strong associations to circumstances stemming from the social determinants of health and the collective elements shaping a participants' decision-making abilities. Social drivers and cultural influences such as beliefs in traditional healing and medicine, the taboo nature of talking about the colon or cancer and fatalistic attitudes were coded as the social barriers driving avoidance of participation in preventative screening.

Disengagement with health care and preventative FOBT CRC screening was another barrier associated with feelings of disempowerment at GP visits, medical mistrust, perceived discrimination/racism, and the belief that health care providers (HCPs) withhold valuable information. Medical mistrust was coded as a barrier to screening in 15 studies and was associated with episodes of trauma, perceived discrimination, racism or marginalisation. Participants frequently spoke of low self-advocacy or an inability to speak up and ask questions during HCP engagement, leaving participants feeling ill-informed on bowel cancer prevention and early detection. One Indigenous participant stated, ‘…and a lot of our Māori are frightened to ask questions…so they sit and they hear all these flash words and it can be quite intimidating…they fear that if they ask a question it will be considered a dumb question…So a lot of our people do sit there in a real whakama state [withdrawn] about even, you know, asking simple questions.’46 Low satisfaction following medical visits in the absence of co-created experiences and decision making between patient and HCPs was also a common theme. This was particularly relevant to data coded from USA publications where federally organised CRC screening programs do not exist.

Complex sub themes surrounding shame for some culturally diverse groups was coded in 50% of included publications. Shame, embarrassment and discomfort stemmed from not only the social and cultural taboo and undesirable nature of dealing with faecal matter, to the perceived lack of privacy in homes for some Indigenous rural/remote participants.

While LGBTQI+ communities were not openly represented in any of the study yield, one participant expressed experiences of marginalisation around a physical disability and expressed difficulty accessing the health care system which was further compounded by heteronormative biases surrounding assumptions about sexuality and an inability to be truly ‘seen’ during HCP interactions.

3.5 Behavioural barriers

In this instance, behavioural barriers were identified as the personal beliefs/actions that shape decision-making abilities and choices surrounding health, on the individual level. Behavioural barriers included the sub-theme of only engaging in health care when sick, perpetuating the lack of engagement in preventative health services for priority populations impacted by the social determinants of health. This was characterised in the following statement from a paper representing rural and remote populations ‘We live in a rural area, so it's not a high priority as far… you know, if a person does not get sick to where they can work, they typically do not go to the doctor. You know we just do not run… preventative maintenance is not done here’.24

Fear and its association with locus of control was thematically relevant in 60% of studies and commonly linked to statement surrounding fear or cancer diagnosis and beliefs that cancer cannot be cured or prevented. One participant stating, ‘I think—well from what a few people have said—and I think this is the general view of the Aboriginal community- that if you’ve got cancer you’re going to die so you just give up, there's no point [in undergoing CRC screening]’.53

Low self-efficacy and the confidence in one's ability to successfully complete a FOBT was coded in 33% of included studies. Participants exploring this barrier within the included studies expressed difficulties around the screening modality, low confidence in their ability to use the FOBT and the need for additional support to successfully complete the kit.

3.6 Economic barriers

Economic barriers have been defined as financial and infrastructure barriers that impede a person's ability to act on decisions that will positively impact their health. Information asymmetry is an economic phenomenon that describes a circumstance where one party holds greater power or benefit as a result of holding a higher level on knowledge or information over another party. Information asymmetry and lower levels of general knowledge and awareness on FOBT based CRC screening was coded as a barrier in 92% of included studies (n = 44). This lack of understanding relating to FOBT CRC screening was a perpetual economic driven denominator contributing to low-risk perceptions throughout synthesised studies and included all population groups.

Lack of knowledge about CRC was further expressed by many CALD and Indigenous peoples with the belief that they were protected as a virtue of race. CRC was frequently cited as a western disease and not something that affected their people. One participant from a study of Indigenous people stated, ‘I’ve never thought of it this way, but I’ve been told that many Native American populations just don’t think that Native Americans get cancer, because the statistics are so low…and I don’t think that a lot of times their healthcare providers or their rural locations have all the information necessarily to provide’.24 Participants stated that CRC is not often discussed within communities, and there is little education infiltrating cultural and behavioural norms or within the limited time allocations in GP visits.

Further economic barriers to FOBT based screening included the need for financial support to complete the screening process and taking unpaid time off work.12, 13, 20-22, 27, 29-31, 52

3.7 Interface/technological barriers

Interface or technological based barriers were coded when a system-based barrier was identified as impeding the ease of access to FOBT screening. Kit aesthetics, lack of cultural support/cultural competency, complexity of languages on FOBT kit/instructions and language barriers with HCPs contributed significantly to the accessibility and equitability of CRC screening.

Language barriers extended past participants of Non-English-Speaking backgrounds (NESB) and CALD groups to Rural and Remote and Low SES communities. Language barriers and the need for translational assistance to enable participation was a result of medical jargon, confusing instructions and language discordance. If a support person perceived the kit as being of low importance, then a participant's opportunity to complete the preventative health action was compromised. This was cited in papers representing both CALD and disability groups and is embodied in the following quote, ‘She [my mum] said to me, there's a letter for me from the doctor. I came and looked at it but I didn’t put that much emphasis on the importance, I didn’t encourage her to take up’.44 Similarly, the need for physical assistance to complete the stool sample was coded for people with a disability. This, along with co-morbidities and lack of HCP support contributed further to feelings of disempowerment and inaccessibility to FOBT screening. Unmet patient navigation needs and the requirement for additional support was thematically relevant in 46% of included studies and spanned across all included population groups.

3.8 Interpretation

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative systematic review to assess the empirical evidence surrounding barriers to FOBT CRC screening for populations impacted by the social determinants of health.

Consistent with past quantitative and mixed method reviews, behavioural and economic barriers such as low health literacy and low utilisation of health care due to past negative experiences is typical for populations impacted by social and economic disadvantage. Our study findings highlight that in the absence of both health literacy and strong patient/HCP relationships, a person's ability to access, process, perceive value and act on health information to enhance wellbeing, is compromised.

Participant statements surrounding the inherent need for support and patient navigation to enable equitable access to screening was echoed across all priority population groups. Consumer driven solutions that aim to mitigate fear-based beliefs and social/cultural norms is one way to increase the value placed on the lifesaving abilities of FOBT based screening.9 Similarly, findings from a recent review of the Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program emphasise the potential for additional patient navigation and support to increase participation and the accessibility of FOBT screening for various population groups.

The identification of asymmetric information as one of the leading drivers of inequalities in FOBT based CRC screening was a novel interpretation of findings in this review. Information asymmetry occurs when one party has better quality information than another party, posing a serious threat to risk perceptions and perceived health care value for some groups.59 In the instance of FOBT based screening, the power imbalance seemingly exists due to the language HCPs and governments use when promoting participation in FOBT based CRC screening. While this language may be useful and increase value perceptions and participation within the general population, it proves to create a power imbalance and further barriers to access for diverse groups. The engendering of inaccessibility to screening from a policy/system level in combination with the stresses and complexities of everyday living, placed screening as a low priority for many groups within the included studies. Consumer value creation can be achieved when gaps in knowledge, locus of control and self-efficacy are addressed, and wellbeing outcomes are realised for a consumer.60 Without the consideration of populations experiencing inequality in the accessibility of preventative health services, we run the risk of increasing the social gradient and the disparities between good health and poor health between populations. Addressing social justice and health equity, requires extending the success of CRC screening to diverse populations. An auspicious environment to enhance the potential of FOBT based CRC screening seemingly exists within the patient/doctor relationship. Enabling diverse communities to see the value in screening through education and knowledge has the potential to break down many of the barriers identified within this review of the literature. To ignore the inclusion of priority populations in policy and system level planning is to deny the full economic and population wide potential of screening for CRC through FOBT.

We anticipate that these findings will be equally relevant for a range of stakeholders including policymakers, physicians and public health workers who are invested in increasing the equitability and accessibility of CRC screening throughout all levels of policy, planning, implementation and evaluation.

3.9 Limitations

This systematic review is the first to focus on the qualitative evidence surrounding the barriers to FOBT screening for priority population groups. Some limitations to the study methodology and data synthesis may exist. A methodologically rigorous approach was adopted throughout the search strategy, however, there is still a risk that some publications may have been missed. We utilised the support of a highly skilled medical librarian to review our search strategy and results to help mitigate this concern. Further limitations exist in the relatively small number of publications across each respective population group with CALD groups heavily saturating data findings. Groups such as LGBTQI+, disability and rural and remote have contributed significantly less to the overall study findings and may have added further to the system level or technology-based barriers to accessing CRC screening. Finally, this qualitative systematic review was limited to study findings published in English.

4 CONCLUSION

This review identified the complexities of FOBT CRC screening accessibility for diverse populations and the system level inhibitors that can work to prevent participation. Groups from socially and economically diverse backgrounds often described the low prioritization of preventative health and CRC screening with indication of poor knowledge and understanding surrounding the potentially lifesaving value of completing the kit. All identified priority populations within the included studies referenced an inability to self-advocate for their health care needs, further reflecting poor patient/physician relationships commonly cited as a biproduct of marginalization, discrimination and general mistrust of medical professionals. This interpretation of findings suggests that patients who are at risk of poorer health outcomes require more time and resources within the medical setting to ensure individualized patient centred needs and education are being appropriately met. Access to preventative health screening is a privilege that should be shared regardless of social or economic circumstances.

This review can help health professionals address the exclusion of diverse population groups in cancer screening and move beyond the responsibility of the individual to a focus on addressing the asymmetric information driving low value perceptions of FOBT based CRC screening. To fully understand the system level and technological barriers preventing equal access to screening future studies should focus on the patient/clinician relationship and the systems that support and encourage greater engagement in FOBT based CRC screening.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nicole Marinucci, Gerald Holtmann and Natasha Koloski: Conceptualisation, investigating methodology, project administration. Nicole Marinucci and Naomi Moy: Formal analysis. Nicole Marinucci, Naomi Moy, Gerald Holtmann, Natasha Koloski and Ayesha Shah: Writing—original draft. Rebekah Russell-Bennett, Jacquie McGraw, Uwe Dulleck and Glenn Austin: Writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the School of Medicine Librarian, Dr Marcos Riba who assisted with guiding the literature search. Further acknowledgement goes to Ms Emma Pearse for her assistance with screening articles against the criteria. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the Department of Gastroenterology, Princess Alexandra Hospital.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.