Young children's use of blue spaces and the impact on their health, development and environmental awareness: A qualitative study from parents' perspectives

Abstract

Issue Addressed

This study examined how families with young children access and use different types of blue spaces and the health and development benefits, and potential negative effects.

Methods

Parents(n = 25) of young children across four coastal communities in Western Australia were recruited via purposive sampling to participate in interviews. A generic qualitative study design grounded in the pragmatism paradigm was utilised.

Results

Beaches were the most frequently used blue space for families all year around, however families did not necessarily attend their closest beach. This appears due to certain beach features making them more or less attractive for use regardless of the distance from home. Parents perceived blue spaces as health promoting due to the increased physical activity children did in and around these spaces. They also reported blue spaces could be positive for child development, contributing to the development of identity. Blue spaces were also perceived to promote children's environmental awareness and environmentally friendly behaviours. However, blue spaces could also be potentially risky environments for families with young children.

Conclusions

The findings highlight blue spaces are an important setting for supporting children's health, development and environmental consciousness.

So What?

It is important to protect natural outdoor environments such as blue spaces for future generations. The findings can be used by governments and policy makers to improve the quality (features and amenities) of blue spaces and positively impact how often families (including those with dogs) use blue spaces and the benefits they experience.

Abbreviations

-

- BEAT

-

- BlueHealth Environmental Assessment Tool

-

- IRSD

-

- Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage

-

- SES

-

- socio-economic status

1 BACKGROUND

Children grow, develop, and learn in various social and physical contexts.1 The physical environments' (including the natural outdoor environment) influence on child health, development and wellbeing is an emerging area of research.2 Natural outdoor environments (such as blue spaces) are associated with positive physical health benefits, enhanced mental health and wellbeing and environmentally friendly behaviours.3, 4 Much of the research on natural outdoor environments has focused predominately on green spaces (ie, open land with natural vegetation, parks and trees)5 and to a much less degree natural blue spaces. And while there is potentially overlap between the health benefits of green and blue space, it is hypothesised there are differences in the mechanisms through which blue compared with green spaces lead to health-related (and other) benefits.3, 4 Natural blue spaces include visible, outdoor, natural, or man-made surface waters (such as oceans, rivers, swamps, creeks or lakes).3, 4 Blue space research has mostly focused on adults with very few studies in children, particularly young children.3, 4 While many of the proposed pathways through which natural outdoor environments impact health and wellbeing may be similar for adults and older children, younger children process external stimuli differently and have different sensory experiences to adults due to their brain developmental phase.6

To date only a few studies have investigated the impact of blue space on children's health, development or wellbeing. Quantitative studies report a positive relationship between proximity to the coast and physical activity.3 Qualitative studies7-9 suggest blue spaces can be locations supportive of spending quality time with families and friends, thus supporting prosocial behaviours and relationships. More broadly blue spaces have many characteristics which support reflection, and restoration. Adults have reported being less stressed in blue spaces due to the ever-changing environment such as waves and wind, providing something to observe and reflect on.8 While there are many benefits associated with children interacting with blue space, it is important to consider the potential negative impacts such as drowning, increased sun exposure and exposure to pollution. For example, globally, drowning is the leading cause of unintentional deaths in children, with the greatest burden in young children less than 5 years.10

Emerging evidence suggests blue space exposure may promote environmentally friendly behaviours7, 11, 12 and that these behaviours potentially affect individual and population health and wellbeing.13 Furthermore, research suggests children can exhibit pro-environmental behaviours (eg, picking up litter) unprompted by their parents when spending time in coastal areas.7, 12, 14 Overall, the evidence base around children and families blue space experiences is limited and to date there has been no research to investigate how young Australian children and their families use and interact with blue spaces, the associated health and developmental benefits, the facilitators and barriers to their use and the associated pathways and mechanisms in which the benefits manifest.15

Furthermore, most research on blue space and health has been conducted in European countries16 with little undertaken in countries such as Australia based in the Oceania region. This is important because Australia is surrounded by blue space, with Western Australia having the longest coastline (12 889 km of mainland coast). Furthermore, over 91% of Western Australians live in coastal areas17 compared to 41% of Europeans.18 Given the unique context of Western Australian families, it is important to explore how families use and interact with blue spaces. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore Western Australian parents' perceptions of how their families, particularly young children interact with blue spaces and the perceived impact on young children's health and development, and the barriers and enablers to using blue spaces.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

A generic qualitative design (a design not guided by an established set of philosophic assumptions19), grounded in the pragmatic paradigm was used to guide the study and subsequent methods.20 This study adhered to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (Table S1). A qualitative approach was deemed the most appropriate method because it enabled the interpretation and discovery of experiences19, 21 from the perspective of parents to: (a) better understand the facilitators and barriers to accessing and using natural blue spaces, (b) how the quality of these spaces' affects use, and (c) the perceived benefits and risks of spending time in these spaces. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee reference number: 2021/ET000722.

2.2 Participants

Purposive and snowball sampling was used to recruit participants who satisfied the study criteria: Participants had to live in one of four coastal community in the Perth Peel (Western Australia) region and have a child between 2 and 10 years of age. It was not a requirement of participation in the study that families needed to visit or use the coast or any blue spaces. The four coastal communities were chosen based on socio-economic status (two residential pockets) of high socio-economic status (SES) and two low SES, derived from the Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD).22 The IRSD summarises a range of information on disadvantage (eg, numbers of low income households, unemployment, poor English spoken) at an area level(such as suburb or slightly larger community). The two low SES coastal communities had IRSD scores in deciles ≤3 at a national level indicating relatively high levels of disadvantage. The two high SES coastal communities had IRSD scores in deciles ≥8 at a national level indicating relatively low levels of disadvantage. Geographical location was also considered (two communities north and two south of the Swan River) to ensure a range of blue spaces. Interviews rather than focus groups were conducted to reduce large gatherings in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants were recruited primarily via social media (Facebook) with geolocation used to specifically target the postcodes across the four coastal pockets. Existing stakeholder networks (Consumer and Community Reference groups and Playgroups) and flyers in local shops were also used.

Participants received participant information, a consent form and a pre-interview demographic and blue space use survey via email. An interview was scheduled at a time and place that was convenient to the participant and researcher and informed consent was obtained, including permission to record the conversation. Of the 32 parents who expressed interest in the study, 25 participated in an interview. Considering the diverse nature of participants' socio-demographic background, the rich and complex stories that emerged, balanced with practical constraints around time, feasibility, and funding23 this sample size was deemed sufficient.

2.3 Interviews

Research looking at families interactions with blue space7 informed the development of an interview guide (Appendix S2) and blue space use survey, which was reviewed by all authors for content validity. A copy of the blue space survey is available from the first author on request. The interviews were semi-structured, allowing discussion and exploration of experiences. Interviews were conducted one-on-one, face to face (n = 7) or via phone (n = 15) or online via Microsoft Teams™ (n = 3) in October and November (Spring) 2021. Where permission was granted interviews were audio-recorded -and transcribed (n = 21), with the remaining four interviews recorded via note taking. Upon completion of the interview, participants were offered $10 (AUD) as a token of appreciation for their time.

At the start of the interviews, the process was explained, that there were no right or wrong answers to questions—just ideas, experiences and opinions and that participants could stop at any time. Participants were asked if they had any questions and if they gave permission to record the interview. At completion of the interview, participants were thanked and invited to ask any questions. Field notes were taken after all interviews for reflexivity. The field notes included how the interviewer felt the interview went, initial thoughts on key themes which arose, any new or contrary themes and any other issues which arose. These notes contributed to the characteristics and reflexivity statement (Appendix S2) and were reviewed during analysis to ensure personal bias did not drive the thematic analysis.

2.4 Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse parent-reported socio-demographic factors collected as part of the pre-interview survey. Transcripts were checked to ensure they were coherent before they were imported to NVivo™ where the data was overseen, interrogated, and stored for analysis. Data were analysed using Braun and Clarke's guideline to thematic analysis.24 Data were coded through inductive codes generated from the data as well as informed by concepts represented in the research field.20, 24 Initial codes were collated into potential themes that were subject to an ongoing process of review and refinement to best reflect the data and organised into a comprehensive and coherent framework of themes.24 Initially the first author identified potential key themes and subthemes. The second author reviewed the coding and then the thematic summary was agreed upon by both authors. All authors reviewed the framework of themes and provided input around defining and naming themes. When reporting the results, participant quotes were presented to represent the major themes.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample demographics

Most (84%) participants were female, had an undergraduate degree or higher (60%), a third had a trade or TAFE qualification (32%) and 16% had graduated from secondary school or less. Most parents were in a heterosexual relationship (92%), and 8% were not currently in a relationship of any orientation. There were similar numbers of parents residing in high SES (56%) and low SES communities (44%) and 44% of families had a family dog. There were 18 boys aged 10 and under with a mean age of 5.4 years and 27 girls with a mean age of 4.8 years old. There were 13 siblings (9 boys and 4 girls) that were aged 11 years and over.

3.2 Frequency of use and distance to most used blue space

The beach was the most frequently used blue space by families (Table 1), with average use highest in summer (one or more times per week) compared with winter (around once a month). Families lived on average (4.4 km) from their most used beach, with those residing in higher SES coastal communities living closer (3.1 km) than those in lower SES coastal communities (5.6 km). Most families exclusively drove to the beach, and several used a mixture of active transport (ie, walking, riding a bicycle or scooting to the beach) and driving. Rivers were the next most frequently used space by families, followed by the lake, swamp and creek.

| Overall (n = 23) | High SES (n = 13) | Low SES (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean distance to most used beach | 4.40 km | 3.10 km | 5.60 km |

| Mean frequencya of beach use in summer | 1.57 | 1.70 | 1.40 |

| Mean frequencya of beach use in winter | 2.70 | 2.62 | 2.90 |

| Mode of transport to beach: | n = 23b | ||

| Exclusively active transport | 4 | 4 (31%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mixture of active transport and driving | 7 | 4 (31%) | 3 (30%) |

| Driving only | 12 | 5 (38%) | 7 (70%) |

| River mean frequencya of use | 3.35 | 3.53 | 3.10 |

| Mean distance | 26.32 km | 19.21 km | 35.57 km |

| Lake mean frequencya of use | 3.57 | 3.54 | 3.60 |

| Mean distance | 18.16 km | 21.06 km | 12.42 km |

| Creek waterfall mean frequencya of use | 4.22 | 4.08 | 4.40 |

| Mean distance | 83.75 km | 58.96 km | 137.25 km |

| Swamp mean frequencya of use | 4.13 | 3.69 | 4.70 |

| Mean distance | 5.94 km | 4.73 km | 12.00 km |

- a Frequency scored on a scale 1 to 5: 5 = never, 4 = rarely (less than once a month), 3 = sometimes (once a month), 2 = often (once or twice/week), 1 = very often (3 or more times/week).

- b Qualitative data was taken from 25 participants, 23 of whom fully completed the demographic and blue space use survey.

3.3 Key themes

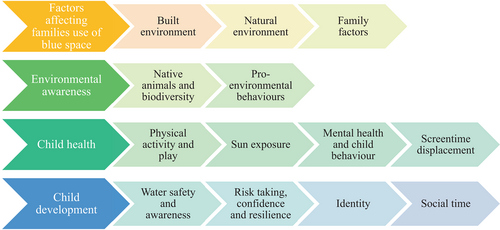

Beaches were the most used blue space which participants almost always referred to in the interviews. Four main themes were identified, with several sub-themes (see Figure 1) providing an in-depth understanding of the ways families used blue spaces, particularly the beach and how parents perceived children's health, development and environmental awareness could be impacted by spending time in these places. The themes were “Factors affecting use,” “Environmental awareness,” “Child health,” “Child development.”

- Theme 1: Factors affecting families use of blue space.

3.3.1 The built environment

Our most local beach, we don't go there just because of the parking issues. (Parent 22, Mother)

Ramps rather than stairs were discussed by most parents as something that made a beach visit easier as a family. It helped with facilitating getting equipment, children and the family dog safely down to the beach. Toilets and showers meant families could spend longer amounts of time at the beach. Adjacent green space and the presence of food outlets made the trip to the beach more convenient for some families.I guess it is the busy car parks…It's not just the pathways down to the beach. It's also accessing other ways as well. Generally going down, I have a bit of gear so it's not really appropriate to catch a bus and yeah, and not that easy to take a bike either and plus there's hardly anywhere to put a bike…there's nowhere to park your bike up that's safe. (Parent 22, Mother)

Shark nets, and a patrolled beach, whether it was a surf lifesaving club or lifeguards made some parents feel more comfortable about letting their children swim and swimming themselves.There's the grass right there. And there's all the paths and there's the shops…cafes. All that stuff makes it, way, way easier because you can just drop in… Just the fact that you can just get there (on the ramp to grass area) without having to go down all the steps and stuff, you just like walk straight onto it, makes it much, much easier. (Parent 14, Mother)

I was thinking well it's nice to kind of have somewhere that you feel safe swimming (like) the shark net (Parent 1, Mother)

There is a surf lifesaving presence at most of the local beaches that we go to. And not that we've ever had to access it. But there's a confidence that you have being at the beach, when you know that if something did go wrong, that there's a service there that have experts that will help you. (Parent 7, Mother)

3.3.2 The natural environment

My kids are both very young. So I guess a lot of the time, too, if it was too hot to go to the beach… Even if they're wearing a hat and sun cream and long sleeve bathers, you don't want to be out in the heat for too long. And then even sometimes just getting from the car to the water. If it's too hot, it can be difficult. (Parent 3, Mother)

I guess knowing like the weather reports, knowing that it's going to be nice on the beach. So you don't pack the whole car, get down there and find the waves are enormous or its blowing a gale. (Parent 3, Mum)

3.3.3 Family-related factors

When the babies were like really little we didn't spend as much time at the beach. I spend more time at the beach once they're more in the walking kind of level. Because they eat sand and all the (rubbish) that's on the beach. But once they start walking, we do tend to take them more to the beach. (Parent 13, Mother)

Other things get in the way. Other activities, both kids do gymnastics and dancing and that sort of thing and swimming lessons at the pool and that sort of thing. And then my wife and I are both studying and working full time. So we sometimes have that factor to consider. (Parent 9, Father)

We generally all just go for walk (to the beach) with the dog. And then we'll just have a quick swim and then come back home. But a lot of the time it's with the dog nearly. (Parent 9, Father)

- Theme 2: Environmental Awareness

Parents perceived their children could develop an awareness of the natural blue environment, noticing native animals and the biodiversity that blue spaces had to offer, potentially prompting pro-environmental behaviours in their children. Parents also spoke about the risks that native animals, particularly sharks could pose to their children.

3.3.4 Native animals and biodiversity

Another interesting one, right is we've found from going to lake and the ocean, that their knowledge of biology like is really improving, because, you know, you can see sea creatures… on the sand they saw a starfish the other day, they asked me, what the names of the birds are, all that sort of stuff. But it also seems to fuel their imagination, and all that sort of stuff. (Parent 5, Mother)

So while I was saying before, that I'd feel comfortable letting my son go to the beach with his friends, I'd be a little bit worried about them, you know, walking through the dunes or anything like that, just because there are snakes around at the moment.

Well definitely, I'm worried about shark attacks. I encourage my son to surf… So I do sometimes worry that I'm encouraging him to surf and that something may happen to him. (Parent 10, Mother)

3.3.5 Pro-environmental behaviours

They were collecting shells, but they were also like picking up bits of rubbish and bringing it back to chuck out when we left. And they know…we do live in a lovely area with a lot of- there were dolphins yesterday, you can always watch the birds like dive and they catch the fish… And you can see the fish, like in the water… So it's like really good for teaching them those sorts of things. Like seeing all the living things that get washed up and die…I think that's really good in terms of like raising their awareness of all the environmental impacts of rubbish and whatever, contaminating the water. (Parent 14, Mother)

So I think that all our kids have an environmental way awareness built into them about coastlines and marine animals and the health of our oceans, just because they actually they know it, they've actually physically used it and they value it as part of their everyday life not just sort of esoteric sort of idea like tigers in you know, in India… I think environmentally, it's incredibly valuable for people to actually touch and feel something that allows them to be more aware and more respectful. (Parent 7, Mother)

- Theme 3: Child Health

Parents discussed how they perceived spending time in blue spaces could affect their child's health in relation to “physical activity and play,” “sun exposure,” “mental health and behaviour,” and “screen time displacement.”

3.3.6 Physical activity and play

The most common activity we do as a family is to then walk probably for about a kilometre along the coast, on the sand and then the kids play… And we'll go for a swim. We often take our goggles so we can, you know, do laps… In terms of their physical activity, I think the benefits of spending time at the beach are obvious in that regard in that they're walking, running, climbing, swimming. So I think those are huge benefits of attending the beach, our children are very active. (Parent 10, Mother)

3.3.7 Sun exposure

I think now the sun has become a bigger concern for us - certainly wasn't a big thing when I was young. We didn't really, I guess we didn't realize how bad it was to have too much. So now…we restrict ourselves generally to, to morning visits where the suns not too intense. You know, making sure the kids they have cream on if he's going to be going down there a bit later in the day, or if we're going to be down there for a while. (Parent 6, Father)

3.3.8 Mental health and behaviour

I think being outdoors in general is good for mental health. And you're happier when you're outside in the sun. And you tend to go to water kind of beach and river places, when it's a nice sunny day. I think it's really good for mental health to be at the beach. There's something calming about the water. (Parent 3, Mother)

We walk down to the beach and we have some time at the beach and walk home - he is exhausted. Which is good because he will sleep well, he's just better behaved… when he's outside and he's running around you know he's … I'm gonna say a happier kid…a bit better behaved in that he's not, you know he's not bored. (Parent 1, Mother)

3.3.9 Screen time displacement

You don't really ever take devices down there…It's just play and hanging out as a family. And that's why we like it. (Parent 16, Mother)

You'd have to put your phone away because you're in the water or (so) you don't get sand in your phone. The phones are packed away in your bag. You get more quality time with your family. (Parent 6 Mother)

- Theme 4: Child development

Parents discussed how they perceived spending time in blue spaces could positively affect their child's development including “water safety and awareness,” “risk taking, confidence and resilience,” “identity,” and “social time.”

3.3.10 Water safety and awareness

I guess for kids that you know, they learn safety around the water. So yeah, you can teach them about rips and currents and things like that. Also the different depths and then waves come in. And then there's obviously like their development so like, here they have different senses and textures with the water and the sand and rocks and shells. (Parent 22, Mother)

3.3.11 Risk taking, confidence and resilience

Being sporty really helps her manage her emotions because she's used to succeeding all the time in academic life… Watching her learn how to surf and bodyboard when she's actually not good at it straightaway, and she has to learn to develop resilience and perseverance as a skill because it's not something that is picked up easily… it also helps them manage their emotions, failing or getting frustrated and working through those emotions as well. (Parent 5, Mother)

3.3.12 Identity

Having the outdoors being something that's just accessible to you and feels like a part of your story and something that you love and you understand and you're not afraid of bugs … it has a huge impact on how you view the environment and then how you treat the environment. So environmentally, I think it has a huge impact where the kids develop an awareness and a comfort with the outdoors whatever it comes in. (Parent 7, Mother)

Culturally, connecting to Country is a massive thing for us. So then needing to learn about the land that we're living on, and what lives there and we talk about dreamtime stories as well. Of what area we're in at the time. And just knowing what is keeping us alive, like the trees that you know, produce air we talked about which ones are better than others, we talked about which ones have what animals all of that and it's just relaxing, and they just seem to be more calm and there's no stress for them. (Parent 13, Mother)

3.3.13 Social time

It has a huge, positive impact on our family spending time (together), especially outdoors, but especially around water. It's partly to do with the fact that my husband and I, we have very happy memories and very strong childhood memories of ourselves spending a lot of time around water as kids. So we want to replicate that. But it's not only just for kids, it's also for ourselves as well. (Parent 7, Mother)

My wife and I will walk ahead and the girls sort of potter behind. And this gives us time to talk. And the dog will stay around our feet, but we don't have to really manage him. So…it's good. And it sort of grounds you, I think sometimes it's good to reconnect with each other… And it does have a calming influence. And it's nice to sort of be out in the fresh air and smell the ocean. (Parent 9, Father)

4 DISCUSSION

This study examined how family's access and use different types of natural blue spaces and the perceived effects on young children's health and development. Parents shared how blue spaces could develop children's awareness of natural spaces and how this awareness could lead to pro-environmental behaviours. The findings also illustrated how changes could be made to the built and natural environment to support families to use and benefit from blue spaces more. To our knowledge this is the first study looking at young Australian children and their families residing in coastal communities and how they interact, frequent, and use blue spaces.

4.1 Factors effecting blue space use

The beach was the most used blue space, which is to be expected considering participants were recruited from coastal areas. However, the most proximal beach did not necessarily equate to it being the most used. This was mostly due to the features of different beaches being more or less attractive to families. Parents discussed many modifiable built and natural environment features that effected their beach use. Parking, bike access, showers/toilets, adjacent greenspace, shade, surf-life saving and lifeguard patrols, ramps to the beach, access to cafés and whether the beach permitted dogs all factored into decision making around which beach families chose to their time at. In addition, grassed areas adjacent to the beach, with family-friendly amenities made family beach visits more enjoyable. Given most features within or near blue spaces are modifiable there is a need for local governments to consider family-friendly amenities when planning for community use of blue spaces.

Some parents reported being able to take the family dog with them to the beach influenced which beach they could visit and thus how they got there (drive or active transport). A large proportion of families in the study had at least one dog (44%). U.S. parents report being able to bring the pet to the beach as the third highest priority when visiting the beach.25 An Australian study suggests beaches could offer a safer dog walking experience than suburban parks due to the open space and also that combining personal exercise with the needs of the dogs was a motivating factor for beach use.26 Both of these studies called for access to more dog friendly beaches. In other Australian states such as Victoria26 and South Australia27 dog walking before 9 am and after 7 pm (**excluding those which are national park) is permitted at most beaches (excluding those which are national park). While dog regulations, wildlife protection and conservation of blue spaces should be considered, this option provides a balance between dog-owners (up to 40% of the Australian and U.S. population28) and non-dog owners, allowing both to use the space and benefit.

Overall, more research is needed on the quality (features) of blue spaces especially in relation how this varies by SES and geographical locations. The BlueHealth Environmental Assessment Tool (BEAT)29 was developed to assess the physical, social and aesthetic attributes of blue spaces for the general community. It measures modifiable blue space features including parking, ramps, toilets, shops, lighting, proximal greenspace, presence of lifeguards as well as attractiveness. Future research could test the BEAT for use in capturing blue space access and quality as it relates to child health and development. The findings from the current research suggest items such as parking, measuring proximal greenspace and whether it's a dog friendly beach would be particularly important.

The features of blue spaces also impacted on families' choice to drive or to actively commute (walk or cycle) to the beach. Active transport has many health, wellbeing, and social benefits.30 Furthermore, active transport can have a positive effect on the natural environment, reducing air and noise pollution as well as car emissions.30 Despite living in coastal communities most families drove to the beach. Poor access to public transport and parking fees were barriers to visiting blue spaces. Access to blue spaces could be more equitable for families by ensuring walkable streets and free parking around these areas as well as public transport options.

4.2 Environmental awareness and perceived effects on child health and development

Blue spaces were perceived by parents as opportunities for children to take in the biodiversity of these spaces, potentially prompting environmental awareness and pro-environmental behaviours. Some parents reported how their young children spoke about pollution in relation to the litter they saw at the beach. Eco-anxiety in children is increasing.31 Providing children with “constructive hope”, and everyday opportunities to show they can make a difference and may be a way to combat children's eco-anxiety as well as provide planetary health benefits.13, 30, 32 Blue spaces could be settings for this through the perceived appreciation, and sense of agency that comes with pro-environmental behaviours when interacting with blue spaces. And while time in natural outdoor spaces broadly is associated with pro-environmentally friendly behaviours,3 our findings suggest more research is needed to investigate components of pro-environmentally friendly behaviours (eg, biodiversity, climate change) attributed to interactions with blue spaces and the mechanisms involved in supporting and developing these behaviours. Future research could investigate whether interaction with blue spaces, is a means of mediating eco-anxiety.

Parents also spoke about the risks that native animals, particularly sharks could pose to their children. It is likely this sub-theme emerged because during data collection, a fatal shark attack occurred in the study region.33 It is possible this may have influenced parents' perceptions of risk as it received significant media attention. Alarmist shark media coverage has been suggested to influence parental concerns, yet any threat from native animals in natural blue spaces is minimal compared to the risk of drowning at the beach.25, 34, 35 During the COVID-19 pandemic drownings in young Australian children increased by 9% compared to the 10-year average and 108% compared to 2019.35 Greater awareness around the actual risks of native animals in blue spaces is needed to balance parents perceived concerns.

Parents perceived benefits and risks to their child's health and development from spending time in blue spaces. While sun exposure was seen as a benefit because of its role in vitamin D production; most parents perceived major risks associated with sun exposure from spending long periods of time outside. Overall, parents awareness of the risks associated sun exposure was high and they were well versed in the prevention of sunburn and other adverse effects of excess sun exposure, which is consistent with the Australian literature.36

Engaging in physical activity and play as a family was overwhelmingly the most dominant perceived health and development benefit discussed. Daily physical activity is crucial for a child's health and development37 with national and international guidelines recommending school-aged children accumulate at least 60 minutes per day of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity.38 Blue spaces provide a variety of different forms of physical activity and play options for children,7 such as surfing, swimming, walking and building sandcastles. The social benefits of interacting with others, particularly as a family, encouraged parents to visit the beach more frequently. Parents also spoke of how blue spaces were not conducive to device (eg, mobile phone) use and without the distraction families enjoyed spending time together, supporting family connection and child development. In support of our findings a survey of U.S. adult beach users found that taking children to the beach was the second highest reason to visit.25 A qualitative study in the UK found the beach to be place where families spent time together.7 Combined these findings highlight that the beach can facilitate children's pro-social behaviours.25

Parents shared their perception that blue spaces positively impacted mental health through restoration, via the calming effects of water. Similar findings have been observed in adults whereby blue spaces were reported as calming and positive places for wellbeing.39 In the current study, parents also perceived blue space exposure improved children's sleep and overall behaviour. To date there is little evidence around sleep and blue space exposure, however findings from a recent systematic review on greenspace and sleep showed a positive association between green space use and sleep quality and quantity.40 More research is needed to establish objectively whether blue space is associated with sleep in children and the pathways through which this occurs. While parents had varying swimming abilities, they all deemed that it was important children develop a sense of awareness and safety in and around blue spaces. Water safety and awareness is an important component of being able to interact safely with blue spaces. Parents spoke about how natural blue spaces can be a dangerous place for people who cannot swim. This is not surprising as drowning is the second highest cause of death amongst young Australian.10 Effective evidence-based policy, supervision, education, swimming lessons and water safety are all effective strategies used to reduce the risk of drowning amongst young children.10

Blue spaces were seen by some parents as places in which children could explore risk taking and develop confidence and resilience. Prior research has shown that nature play in green spaces enhances autonomy, resilience, the development of sense of identity in young children.37-39 It is generally accepted that the risks and challenges provided by play in natural environments can nurture emotional understanding, a sense of agency and mastery and accomplishment.41, 42 Further research is needed to confirm these findings in children and blue spaces.

Development of identity, as community members, and connection to Country and the natural environment was perceived by parents to be supported by spending time in blue spaces. In support of our findings, recent research has explored how children access, interact, and manage in urban blue spaces and highlighted the importance of natural blue spaces for children understand their identity,41 wellbeing7 and how they relate to their environment.41 Similarly, studies in adults suggest living in proximity to blue spaces promotes shared place making, belonging, attachment to these spaces, as well as social interactions around it, all interrelated and contributing to identity.42

4.3 Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted considering several limitations. The nature of thematic analysis means the data interpretation may have been influenced by the researchers' prior experiences and knowledge, however potential bias was avoided through a reflexivity diary. Member checking of the transcripts would have enhanced the validity and trustworthiness of this study. The findings were based on parents' perceptions and recollections. Future research should consider using parents perceptions alongside objective measures of blue spaces (geospatial data). While using blue spaces as a family was not a requirement in participation in the study, the value parents place on blue spaces may have affected whether they participated in the research and thus the views of parents who dislike or fear blue spaces may not have been fully represented. The majority of the respondents were female which may impact the transferability of the findings to other population groups. The collection of other socio-demographic measures (such as work status and ethnicity) could strengthen future studies. Lastly, parents were recruited because they lived in a coastal community. The relationship between blue space and child health and development should also be explored in families who have less access to blue space. Importantly, future research should include the voices of young children.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study suggest parents and families in coastal communities use the beach frequently but the closest beach is not necessarily the most used. This in part appears due to the built and natural environment features of blue spaces. Parents perceived there to be a number of child health and development benefits as well as some risks associated with visiting blue spaces. For example, environmental awareness and environmentally friendly behaviours were perceived benefits, indicating that blue spaces could be a health promotion setting as well as a potential setting to reducing eco-anxiety in children. Further research, with a larger sample size, and objective measures of children's health, development and environmental awareness and blue spaces is needed to develop the evidence base.

Our findings indicate that blue space quality (and not just access) is important for family's interactions with blue spaces. It is also important that families have equitable access to high quality blue spaces, and these spaces are promoted to parents to ensure all children receive the health, development and wellbeing benefits identified in this study. Future research should focus on the development of tools to assess the quality as well as access to blue space. Such research would provide evidence of the potential modifiable features of blue spaces to encourage children and families to use and benefit from these spaces more. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of sustaining and protecting natural outdoor environments for future generations, as well as balancing the benefits of using blue spaces with the family footprint on these spaces. The findings can be used by governments and policy makers to improve the quality (features and amenities) of blue spaces and positively impact how often families (including those with dogs) use blue spaces and the benefits they experience.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualisation: all authors. Data curation: Phoebe George; formal analysis: Phoebe George and Hayley Christian; methodology: all authors. Project administration: Phoebe George. Writing—original draft: Phoebe George. Writing—review and editing: All authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all the participants who volunteered to participate in this study and the parents in the PLAYCE Consumer Reference Group for their input around the interview protocol and blue space use survey and sharing the recruitment advertisement. The authors acknowledge the Noongar people are the traditional owners of the land that this research was conducted on and primarily about and the stories, song lines, culture and the relationships which existed long before colonisation. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Western Australia, as part of the Wiley - The University of Western Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received funding from the Telethon Kids Institute Student Professional Development Funding Program, which was used to reimburse participants for their time and participation. PG was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Scholarship and is a student through the Australian Research Council's Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (#CE200100025). HC was supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (#102549).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee reference number: 2021/ET000722.

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable as consent has been obtained for data collection and no identities will be disclosed.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.