Hope and sadness: Balancing emotions in tobacco control mass media campaigns aimed at smokers

Funding information

This study was funded by the Cancer Institute NSW.

Abstract

Issue addressed

Australia has smoking prevalence of less than 15% among adults, but there are concerns that the rates of decline have stabilised. Sustained mass media campaigns are central to decreasing prevalence, and the emotions evoked by campaigns contribute to their impact. This study investigates the association between potential exposure to campaigns that evoke different emotions on quitting salience (thinking about quitting), quitting intentions and quitting attempts.

Methods

Data on quitting outcomes were obtained from weekly cross-sectional telephone surveys with adult smokers and recent quitters between 2013 and 2018. Campaign activity data were collated, and population-level potential campaign exposure was measured by time and dose.

Results

Using multivariate analyses, a positive association between potential exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns and thinking about quitting and intending to quit was noted, but no association was seen with quit attempts. Potential exposure to ‘sadness’ evoking campaigns was positively associated with quitting salience and negatively associated with quit attempts, whereas those potentially exposed to campaigns evoking multiple negative emotions (fear, guilt and sadness) were approximately 30% more likely to make a quit attempt.

Conclusions

This study suggests a relationship between the emotional content of campaigns, quitting behaviours. Campaign planners should consider campaigns that evoke negative emotions for population-wide efforts to bring about quitting activity alongside hopeful campaigns that promote quitting salience and quitting intentions. The emotional content of campaigns provides an additional consideration for campaigns targeting smokers and influencing quitting activity.

So what?

This study demonstrates the importance of balancing the emotional content of campaigns to ensure that campaign advertising is given the greatest chance to achieve its objectives. Utilising campaigns that evoke negative emotions appear to be needed to encourage quitting attempts but maintaining hopeful campaigns to promote thinking about quitting and intending to quit is also an important component of the mix of tobacco control campaigns.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nationally, Australia has seen a decline in the prevalence of smoking over the last 30 years, commensurate with the sustained implementation of comprehensive tobacco control strategies, including tobacco price increases, the introduction of plain packaging, smoke-free places policy and legislation and the use of sustained and visible mass media campaigns.1 In 2019, in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, 15.5% of adults were current smokers, compared to 19.4% of adults in 2008.2 Notwithstanding these decreases, constant efforts are required to further increase cessation and to prevent a possible smoking resurgence3; this is of growing importance with recent research suggesting that the smoking rates have stabilized.2

It is known that mass media campaigns aired at regular intervals with sufficient levels of exposure in the population contribute to reducing smoking prevalence.4-7 Specifically, campaigns that highlight the negative health consequences of smoking and evoke strong emotions, particularly those that use graphic imagery, are particularly effective.4, 8-10 With the link between tobacco control campaigns and decreasing smoking prevalence well established, there is a need to assess which emotional portrayals are most effective at increasing quitting-related activities and discouraging smoking to ensure the gains made by campaigns continue.

Evidence on the differential impact of positive and negative emotions evoking tobacco control campaigns must also be considered within the theoretical context of the role that emotions have in influencing perceptions, cognitions and behaviour.11-13 For the last 30 years, theories have posited that people react to external or internal stimuli by appraising the harm or benefit of the stimuli before developing an emotional response which subsequently influences behaviour.11, 14 Many public health campaigns rely on the creation of an emotional response to a campaign message and that along with their perceived susceptibility, the severity of the risk and the threat of harm15 will result in change in the priming steps of behaviour change and the trialling of new behaviours. The ability of discrete emotions to trigger different behavioural responses is particularly relevant for campaigns, with research suggesting that fear tends to result in efforts to retreat from a threat and positively influence behaviour, sadness may provide a motivation10 to engage in immediate actions to ameliorate the sadness but may not result in long-term behaviour change13, 16 and hope providing a motivator for intentions and behaviours.17 Maximizing the ‘right’ emotional response is a crucial component in the anticipated success of a campaign and more recently, literature has suggested that consideration of how messages can stimulate a range of emotions (not just a dominant one) is required, noting that the emotion that the message evokes will evolve.12

The emotions evoked by tobacco control advertising can be classified as either positive (such as happiness and satisfaction) or negative (such as anger, fear, guilt, disgust or sadness).9, 10, 18-20 Evidence of differential effectiveness for campaigns that evoke negative or positive emotions is mixed for a range of outcomes, such as campaign recall, quit attempts, quitline calls and smoking prevalence.

In relation to campaigns that have elicited negative emotions; campaigns that evoke fear and sadness were seen as believable and thought provoking for recent quitters21; fear-evoking messages may also be important in informing people of the dangers of smoking22 and Richardson et al.19 reported that campaigns that elicited negative emotions had a greater impact on recall than positive emotion-evoking campaigns. Advertisements that elicited higher levels of guilt resulted in conversations that were more likely to contain talk of quitting by smokers.18 A recent study by Durkin et al.10 concluded that it might be more efficient to implement tobacco control advertisements that evoke fear rather than sadness and that advertisements that elicit a negative emotion may be most effective at motivating quitting amongst smokers from lower socio-economic backgrounds. On the other hand, research exploring the association between exposure to campaigns evoking different emotions and call volumes to smoking cessation quitlines found that campaigns evoking negative emotions did not influence call volumes.23

The literature also provides details in relation to the use of both positive and negative emotion-evoking campaigns. The study by Durkin et al.10 also found that combining fear and hope-evoking campaigns leads to increased quit attempts among mid- high-socio-economic background smokers. Campaigns that evoke both positive and negative emotions have been shown to be effective in reducing smoking prevalence, with positive emotion campaigns playing a particular role in providing information on how to quit and a role in enhancing the self-efficacy of smokers.24 Research from the American Tips From Former Smokers campaign is suggestive that the use of a wide variety of emotional appeals (including guilt, anger, fear, disgust, hope, warmth and humour), are effective at motivating smokers to make a quit attempt and nonsmokers to talk with friends and family about the harms associated with smoking.20

In NSW, the Cancer Institute NSW (www.cancer.nsw.gov.au) is a state-level health agency that has developed and delivered comprehensive tobacco control campaigns on an annual basis since 2006. A range of campaigns highlight the negative health impacts associated with tobacco use and encourage smokers to quit smoking (Table 1), with the broadcasting of these campaigns associated with quitting outcomes at a population level.25 This study builds on the evidence presented in the research undertaken by Durkin et al10 but with a different suite of campaign materials evoking a varied emotional response and in a different Australian jurisdiction. The current research explores campaigns (which included campaigns that predominantly evoked hope, sadness and combination of negative emotions) that the Cancer Institute NSW implemented during 2013–2018 and assessed associations between potential exposure to campaigns evoking specific emotions and quitting outcomes including: (i) quitting salience (ie, thinking about quitting); (ii) quit intentions; and (iii) quit attempts. In addition, this research assessed whether associations between quitting outcomes and potential campaign exposure differed according to demographic characteristics of smokers and recent quitters.

| Campaign (ad length) | Emotional classification | Total TARPS | Total weeks | On air datesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hopea | 3409 | 30 | January 7, 2018–March 3, 2018, March 6, 2016–April 16, 2016, March 22, 2015–May 2, 2015, November 2013–December 2013, March 3, 2013–June 15, 2013 | |

| Hope | 278 | 8 | May 20, 2018–June 30, 2018, April 16, 2017–July 1, 2017 | |

| Hope | 2152 | 25 | March 27, 2016–June 4, 2016, February 3, 2013–September 21, 2013 | |

| Hope | 433 | 8 | October 22, 2017–December 2, 2017 | |

| Hope | 740 | 8 | August 2013–September 2013 | |

| Hope | 266 | 5 | March 2, 2014–April 5, 2014 | |

| Sadnessb | 1288 | 15 | March 4, 2018–May 28, 2018, January 8, 2017–March 30, 2017 | |

| Sadness | 1328 | 12 | February 21, 2016–April 2, 2016, February 15, 2015–March 28, 2015 | |

| Sadness | 391 | 4 | September 11, 2016–October 22, 2016 | |

Voice withind (30 sec) |

Sadness | 374 | 5 | October 2013–November 2013 |

| Negative | 2126 | 23 | September 21, 2014–November 15, 2014, May 2015–June 2015, February 2014–March 2014 | |

| Negative | 1247 | 15 | September 24, 2017–October 21, 2017, October 23, 2016–November 27, 2016, May 8, 2016–June 18, 2016 | |

| Negative | 349 | 7 | August 7, 2016–September 10, 2016, June 29, 2014–August 9, 2014 | |

| Negative | 699 | 5 | May 26, 2013–June 29, 2013 | |

| Negative | 475 | 6 | November 9, 2014–December 20, 2014 | |

| Negative | 618 | 6 | December 30, 2012–February 9, 2013 | |

| Negative | 485 | 6 | June 3–30, 2018, October 18, 2015–November 28, 2015 | |

| Negative | 567 | 5 | November 15, 2015–December, 19 2015 | |

| Digital quit smoking | N/Ae | 0 | 148 | August 30, 2015–June 24, 2018 |

- a Hope is classified as a positive emotion.

- b Sadness is classified as a negative emotion.

- c These dates represent the dates that the campaign was on air during the study period, some of these campaigns will have been aired outside the study period.

- d A link to this campaign creative is not available.

- e Not included in emotion classification study as the digital quit smoking campaign included a variety of creative executions over a 2.5-year period which were not possible to classify into one emotional component.

2 METHODS

2.1 Setting

The Cancer Institute Tobacco Tracking Survey (CITTS) comprises a telephone-based cross-sectional continuous tracking survey of adult current smokers and recent quitters in NSW. The telephone survey uses an overlapping dual-frame design to include both landline and mobile phone users. Landline households were recruited using random digit dialing and mobile households were recruited using a random sample of valid mobile phone numbers. Once a household is selected, one adult is randomly selected from within the household. Approximately 40 interviews are conducted each week for 50 weeks of the year, providing approximately 2000 completed interviews each year. Data from all completed interviews undertaken between January 2013 and July 2018 were included in this study. The CITTS is conducted by a research agency on behalf of the Cancer Institute NSW. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (project number: 2017/497).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Quitting-related outcomes

The CITTS collects information on smoking-related cognitions and behaviours, recognition and response to tobacco control campaigns and other policies, and quitting outcomes. Quitting salience (ie, thinking about quitting), was assessed by asking current smokers, ‘During the past two weeks, how often have you thought about quitting?’ With the response options being several times a day, once a day, once every few days, once a week and not at all. Responses were categorised into a binary indicator of whether or not respondents thought about quitting at least once per day in the 2 weeks before the survey.25, 26 Quitting intentions in the past month were determined by asking current smokers who indicated that they were ‘seriously considering quitting smoking in the next six months’, ‘Are you planning to quit smoking in the next 30 days?’. Those who were planning to quit within the next 30 days were classified as having quit intentions. In relation to quit attempts in the past month, smokers were asked ‘Have you ever tried to quit smoking before?’ and if they responded ‘Yes’, they were asked ‘How long ago did you last try to quit smoking?’ Responses were categorised into whether or not there was a quit attempt in the month before the survey. Recent quitters were asked ‘When did you finally stop smoking?’. Quit attempts were dichotomized as those who made a quit attempt in the month before the survey. If the recent quitter stopped smoking more than once month before the interview, they were excluded from these analyses.

2.2.2 Socio-demographic variables

Socio-demographic characteristics of survey participants included age, sex, individual-level socio-economic status (SES) and neighbourhood-level SES. A Heaviness of Smoking Index used a modified short form Fagerstrom questionnaire,27 which uses a combination of ‘time to first cigarette after waking’ and ‘number of cigarettes smoked per day and divided into three categories (low, medium and high)’.28 Change in cigarette price was assessed using the average price per cigarette per week during the study period.10, 29 Individual-level SES,29 was assessed using a composite measure of household income and education.26, 30 High education refers to completing tertiary education (ie, University and TAFE); moderate education is completing the Higher School Certificate (ie, Year 12), and low education is not having completed the Higher School Certificate. High SES was defined as having a household income of more than AUD $80 000 (and any education level), or an income of AUD $40–80 000 and moderate-high education. Moderate SES was defined as either an income below AUD $40 000 and high education, or an income of AUD $40–80 000 and moderate education. Low SES was defined as either an income below AUD $40 000 and low or moderate education, or an income AUD $40–80 000 and low education. Neighbourhood-level SES was determined using postcode of residence and categorised using the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA)25, 31 specifically the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage, which ranks areas in Australia according to relative socio-economic disadvantage.

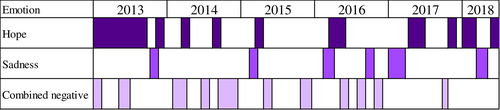

2.2.3 Campaign exposure

Potential exposure to campaigns was assessed in two ways (i) using the number of weeks (time) the campaign was run in the 3 months before the interview and (ii) dose: target audience rating points (TARPs) also in the 3 months before the interview. Potential exposure is a population-level proxy for direct individual-level exposure. TARPs represent the proportion of a specific target audience viewing a program at the time the advertisement is aired and as such are a product of the percentage of the target audience exposed to an advertisement, the average number of times it would be expected that a target audience member would be exposed to the advertisement.25, 32 TARPS are relevant for television campaigns; however, as not all of the campaigns in NSW between 2013 and 2018 were television campaigns (ie, Digital Quit smoking), and so we also examined potential exposure using time (ie, weeks that the campaign ran in the 3 months prior to the interview). Campaign exposure was calculated by summing the exposure (TARPS or weeks) during the 3 months before the interview for each campaign that was classified according to the dominant emotion evoked by that campaign (Table 1). Figure 1 provides a pictorial representation of the timing, and the emotional content of the tobacco control campaigns as they were ‘on air’ during the study period.

2.2.4 Classification of dominant emotions evoked by campaign

The dominant emotion evoked by each campaign was determined using a quantitative ratings study conducted by an external research agency on behalf of the Cancer Institute NSW. A sample (n = 152) of smokers and recent quitters were shown several advertisements (with each respondent being randomly allocated five advertisements to rate from a pool of 18 different advertisements) and asked to what extent each advertisement made them feel sad, angry, fearful, disgusted, guilty, hopeful and happy on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘very’ to ‘not at all’. Consistent with previous research,10 the dominant emotion for each advertisement was coded if an emotion was evoked by at least 45% of the participants and there was no other emotion classification within 10%. When the emotion was evoked by at least 45% of participants, but other emotional classifications were within 10%, the advertisement was coded as ‘combined negative emotions’ which included a combination of fear, guilt and sadness (Table 1). No advertisements were classified as only evoking anger, fear, disgust, guilt, or happiness.

2.3 Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for level of campaign TARPS, age, gender, individual and neighbourhood-level SES, year of survey, quitting intentions, quitting salience and quitting behaviours were calculated. The unadjusted association between each covariate and each outcome (ie, quitting intentions and quitting behaviour), and between potential exposures (ie, TAPS or time) to the emotional content of the campaigns and each outcome was examined. Multivariate modelling was undertaken, in line with the following: (i) the first multivariate logistic model examined the association between potential exposure to dose of emotional content of the campaigns on smoking intentions and quitting behaviours adjusting for all covariates (ie, age, sex, individual-level SES, neighbourhood-level SES, change in cigarette price and year of survey); (ii) the second multivariate logistic model examined the association between potential exposure to the dose of emotional content of the campaigns on smoking intentions and quitting behaviours, adjusting for only the covariates that were significantly (p < .05) associated with smoking intentions and quitting behaviours in the first model; and (iii) the third multivariate logistic model examined interactions between the dose of emotional content of the campaigns and demographic characteristics to determine whether the relationship between emotional content and smoking outcomes differ as a function of these characteristics. Analyses were first run with TARPS as the exposure measure and then time as the exposure. Analyses relating to quitting intentions and quitting salience included current smokers (n = 9656), whereas analyses relating to quitting attempts included current smokers, and recent quitters together (n = 10 140).

Two-way interactions between the emotional content of each campaign and age, sex, individual-level SES, and neighbourhood-level SES were undertaken, and three-way interactions between combinations of emotional campaign content (ie, hope and sadness, hope and combined negative emotions, sadness and combined negative emotions) with age, sex, individual-level SES and neighbourhood-level SES were also undertaken. All odds ratios were calculated per unit increase of 1000 TARPS or 12 weeks to show how an increase in 1000 TARPS or 12 weeks potential duration of exposure to each emotion is associated with quitting behaviours (Davis et al., 2018). This scaling aligns with the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention's (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2014) recommendations for anti-tobacco television campaigns of quarterly media buys between 800 and 1200 Gross Rating Points (GRPs). GRPs are similar to TARPS; however, they do not define a specific target audience. The average total 12-week campaign TARPS were 957 and ranged from 266 to 3409 (IQR: 387, 1298). NSW Population weights were applied to match the population distribution. All analyses were performed in SAS Enterprise Guide 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Socio-demographic profile of survey participants

Of the 10 140 survey respondents, 9656 (95%) were current smokers and 484 (5%) were recent quitters. There was a higher proportion of 25–39 years old respondents (33%; compared with all other ages), males (61%; compared with females), and respondents living in high

socio-economic status areas (40%; compared with low socio-economic status areas) (Table 2).

| N | % | Weighted % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All persons | 10 140 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Age category | |||

| 18–24 years | 1103 | 10.9 | 9.9 |

| 25–39 years | 2320 | 22.9 | 33.2 |

| 40–44 years | 916 | 9.0 | 10.0 |

| 45–55 years | 2213 | 21.8 | 23.2 |

| 55–64 years | 2049 | 20.2 | 14.2 |

| 65–74 years | 1537 | 15.2 | 9.6 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5710 | 56.3 | 60.5 |

| Female | 4430 | 43.7 | 39.5 |

| Individual level socio-economic status (SES) | |||

| High | 3882 | 38.3 | 39.8 |

| Moderate | 3497 | 34.5 | 33.8 |

| Low | 2650 | 26.1 | 25.3 |

| Missing | 111 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Neighbourhood level SES | |||

| 1st (most disadvantaged) | 1902 | 18.8 | 16.6 |

| 2nd | 2087 | 20.6 | 20.1 |

| 3rd | 2486 | 24.5 | 25.6 |

| 4th | 1750 | 17.3 | 18.1 |

| 5th (least disadvantaged) | 1915 | 18.9 | 19.7 |

| Year of survey | |||

| 2013 | 2234 | 22.0 | 22.1 |

| 2014 | 1775 | 17.5 | 17.6 |

| 2015 | 1801 | 17.8 | 17.7 |

| 2016 | 1725 | 17.0 | 16.9 |

| 2017 | 1743 | 17.2 | 17.2 |

| 2018 | 862 | 8.5 | 8.4 |

| Quit attempt in the past 30 days | |||

| Yes | 1260 | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| No | 8838 | 87.2 | 87.3 |

| Missing | 42 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Intends to quit in the next 30 days | |||

| Yes | 2214 | 22.9 | 23.8 |

| No | 2,797 | 29.0 | 29.4 |

| Do not know | 539 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| Missing | 4106 | 42.5 | 41.2 |

| Quitting salience | |||

| At least once a day | 3380 | 35.0 | 34.9 |

| Less than once a day | 6197 | 64.2 | 64.3 |

| Do not know/refused | 79 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

- Note: Quitting intentions and quitting salience was only asked of current smokers (n = 9,656). Survey % refers to the proportion in the CITTS sample; Weighted % uses survey weights and refers to the proportion of the NSW population.

3.2 Impact of hope-evoking campaigns on quitting salience, intentions and attempts

In bivariate analysis, there were no significant results in relation to the association between ‘hope’ campaigns on quitting salience. However, multivariate analysis found that potential exposure (as assessed by both TARPS and time) to an additional 1000 TARPS or an additional 12 weeks of ‘hope’ campaigns was associated with 31% and 27% higher odds of thinking about quitting more than once per day in the previous 2 weeks, respectively (aOR:1.31, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.48 for potential campaign exposure measured by TARPs and aOR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.16, 1.39 for exposure measured by time) (Table 3).

| Salience | Quit intentions | Quit attempts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion | Exposure measure | Estimate (95% CIs) |

Estimate (95% CIs) |

Estimate (95% CIs) |

| Hope | TARPS | 1.31 (1.17, 1.48) | 1.08 (0.94, 1.20) | 0.91 (0.76, 1.10) |

| Time | 1.27 (1.16, 1.39) | 1.10 (1.00, 1.23) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.10) | |

| Sadness | TARPS | 1.07 (0.85, 1.35) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 0.60 (0.41, 0.88) |

| Time | 1.29 (1.03, 1.62) | 1.16 (0.88, 1.52) | 0.66 (0.45, 0.96) | |

| Combined negative emotions | TARPS | 1.05 (0.90, 1.21) | 0.99 (0.82, 1.20) | 1.25 (1.00, 1.60) |

| Time | 1.09 (0.90, 1.31) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.30) | 1.35 (1.01, 1.81) |

- Note: These results are from the final multivariate models, which only include significant covariates.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis assessing potential campaign exposure by TARPs did not demonstrate a relationship between exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns and quitting intentions (aOR: 1.08 95% CI: 0.94, 1.20). However, the bivariate and multivariate analysis assessing potential exposure by time found that potential exposure to an additional 12 weeks of ‘hope’ campaigns was associated with 10% higher odds of having quitting intentions (aOR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.23).

There was also a significant two-way interaction between potential exposure (as assessed by time) to ‘hope’ campaigns and heaviness of smoking (F = 10.77, p < .01), such that for smokers in the heavy smoking group, potential exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns was associated with 33% higher odds of having quit smoking intentions than smokers in both low and moderate smoking groups (aOR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.70). There was also a significant interaction between potential exposure (as assessed by time) to ‘hope’ campaigns and SES (F = 4.68, p = .05), whereby for smokers in the moderate SES group, with every additional 12 weeks potential exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns was associated with 31% lower odds of intention to quit smoking (aOR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.50, 0.97).

Bivariate and multivariate analysis (in relation to current smokers and recent quitters) did not demonstrate a relationship between potential campaign exposure and quitting attempts for ‘hope’ campaigns. There was a significant interaction between exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns and age (F = 12.72, p = .04). For smokers in the 65–74 years age group, exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns was associated with higher odds of making a quitting attempt compared to smokers in the 18–24 year age group (aOR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.62).

3.3 Impact of sadness-evoking campaigns on quitting salience, intentions and attempts

The bivariate analysis in relation to ‘sadness’ evoking campaigns and quitting salience did not demonstrate any significant association. Potential exposure to ‘sadness’ evoking campaigns as measured by time, was associated with 29% higher odds of thinking about quitting (aOR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.62). There were no significant results in relation to ‘sadness’ campaigns and quitting intentions, but potential campaign exposure (measured by both TARPS and time) showed ‘sadness’ campaigns were associated with 40% and 34% lower odds of attempting to quit, respectively (aOR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.88 as measured by TARPs; and aOR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.45, 0.96 as measured by time) (Table 3).

No significant interactions were found between demographic characteristics and sadness evoking campaigns.

3.4 Impact of negative emotion-evoking campaigns on quitting salience, intentions and attempts

There were no significant bivariate or multivariate results in relation to potential campaign exposure to ‘combined negative emotion’ evoking campaigns and quitting salience and quitting intentions. We found a significant association between potential campaign exposure as assessed by both TARPS and time and quitting attempts, with exposure to ‘combined negative emotion’ campaigns associated with 35% and 25% higher odds of attempting to quit, respectively (aOR: 1.35 95% CI: 1.01, 1.81 assessed by time; aOR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.50 assessed by TARPs) (Table 3).

No significant interactions were found between demographic characteristics and negative emotion-evoking campaigns.

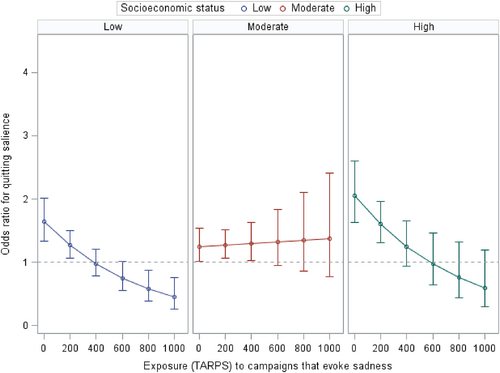

3.5 Interaction of hope and sadness and hope and negative emotions campaigns

There was a significant interaction between potential exposure (as measured by TARPS) to ‘hope’ and ‘sadness’ campaigns (F = 17.74, p = <.0001), such that thinking about quitting after exposure to ‘hope’ evoking campaigns decreased as exposure to ‘sadness’ campaigns increased. There was also a significant interaction between potential exposure (as assessed by TARPS) to ‘hope’ and ‘sadness’ campaigns and socio-economic status (F = 9.42, p = .009) (Figure 2) with thinking of quitting after exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns decreasing as exposure to ‘sadness’ campaigns increased among the high (F = 9.18, p < .001) and low (F = 16.86, p < .001) SES groups, but not the middle SES group.

Furthermore, stratified analyses indicated a significant interaction between ‘hope’ and ‘negative emotion’ TARPS in the moderate SES group (F = 5.10, p = .02), but not the high (F = 3.21, p = .07) or low (F = 0.53, p = .47) SES groups (Figure 2).

3.6 Summary of significant results

The findings are suggestive of positive associations between potential exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns and quitting salience and quit intentions, but not association for quit attempts. Potential exposure to ‘sadness’ campaign were positively associated with quitting salience and negatively associated with quit attempts, whereas potential exposure to ‘combined negative’ campaigns was positively associated with quit attempts.

4 DISCUSSION

This study found a number of relationships between smokers' potential exposure to tobacco control mass media campaigns evoking different emotions and quitting outcomes. Specifically, smokers with greater potential exposure to campaigns that evoked ‘hope’ and campaigns that evoked ‘sadness’ were more likely to report salient quitting thoughts. Smokers potentially exposed to ‘hope’ campaigns were more likely to report quit intentions (in line with research undertaken by Nabi & Myrick,17) whereas potential exposure to ‘sadness’ or ‘negative emotion’ campaigns was not associated with quitting intentions. In terms of quit attempts, smokers who were potentially exposed to ‘sadness’ campaigns reported fewer quit attempts. Contrastingly, smokers potentially exposed to ‘negative emotion’ campaigns were most likely to report recent quit attempts, in line with existing research.10, 19, 24

‘Negative emotion’ campaigns evoked three negative emotions: fear, guilt and sadness. Our findings broadly support that these emotions are associated with quit attempts. This finding is consistent with the study undertaken by Durkin et al10 who found that exposure to advertisements which evoked multiple negative emotions (including fear, guilt and sadness) increased the likelihood of past-month quit attempts (particularly for lower SES areas). However, our study did not find any differential impacts for exposure to combined negative emotions on quitting attempts between SES groups. Many of these negative emotion-framed campaigns utilised graphic advertisements depicting health consequences of smoking; previous research33 has demonstrated the importance and influence of this type of anti-tobacco campaign on quit attempts.

In addition to potential exposure to ‘sadness’ campaigns having a negative association with quit attempts, our results suggest an interaction between ‘hope’ and ‘sadness’ evoking campaigns, and that exposure to a sadness campaign may offset the positive impact of a ‘hope’ campaign on quitting salience. This finding supports the hypothesis posed by Durkin et al10 that exposure to predominantly sadness-evoking advertisements might reduce the likelihood of quitting. It seems that there is a risk that sadness campaigns may lead to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness in smokers, and that rather than bringing about quitting related action they may result in smokers not taking any action, and avoiding seeking help to quit11, 16, 34; this explanation is also in keeping with theories regarding the use emotional focused coping which tends to be used when there is an appraisal that nothing can be done to modify or eliminate the problem.10, 13, 16, 35 Campaigns that were classified as evoking ‘sadness’ tended to highlight the regret at missing out of time or experiences with loved ones which may have a stronger impact on feelings of helplessness.36

In this study, potential exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns had a particular resonance with sub-groups of smokers, potential exposure to such campaigns were associated with quitting salience for heavy smokers and with quit intentions and quit attempts for older smokers. Other research suggests that positive emotion campaigns may be important to enhance self-efficacy when used in combination with negative evoking campaigns.24 Our study found that thinking about quitting after potential exposure to ‘hope’ campaigns decreased as potential exposure to ‘sadness’ increased, and this effect was moderated by SES. While this finding requires greater exploration to understand how best to combine positive and negative evoking campaigns, it may be that campaigns that unduly evoke ‘sadness’ could weaken the impact of campaigns that evoke positive emotions although this may be related to the particular type of sadness evoking campaigns.

The results presented here confirm that the emotions evoked by a campaign are important in designing and planning tobacco-reduction messages and campaigns.37 Evoking a positive emotion such as hope is useful but likely not sufficient to bring about actual quit attempts; whereas a negative emotion-provoking campaign does seem to increase the likelihood of quit attempts but does not seem to influence quitting cognitions or quitting plans. This suggests that population-wide campaigns should target negative emotional responses, particularly fear and guilt,24 to increase quit attempts. There may be a role for the more targeted use of hopeful campaigns aimed at older and heavier smokers. Suggesting that older and heavier smokers may have a number of failed quit attempts and that they require hopeful messages to increase their self-esteem. Furthermore, hope campaigns might overcome cognitive dissonance regarding quitting and quitting intentions, but by themselves do not provide the best opportunity to influence quit attempts, although there is merit in the use of such messages targeting older and heavier smokers. There may also be a role for hope-evoking campaigns that target smokers to influence knowledge, attitudes and beliefs as priming steps of behaviour change and quit attempts. Further research will be needed to determine the ideal combination of these campaigns. Notwithstanding that the advertisements included in our study only evoked hope, sadness and combined negative emotions, as tobacco control efforts target further declines in smoking, it may also be opportune to assess campaigns that induce a broader range of feelings (for example hypocrisy38) on smoking-related behaviours.

5 LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

These results should be interpreted within NSW context of several styles and types of tobacco control advertising since 1983 and it is not possible to account for this exposure in this analysis. Nor does the analysis account for the creative execution or type of media placement, including the more recent integration of digital media.39 Our study does not account for other unobserved noncampaign factors (social and individual factors, illness etc.) that might influence decisions to quit smoking, although our analysis did adjust for tobacco price and heaviness of smoking. These surveys are based on self-report, but since they are estimating psychological intermediates, they are considered acceptable, but still may be subject to social desirability bias. Further limitations of this paper include: the study in the main focuses on a sub-sample of CITTS respondents; it uses potential exposure to the campaign materials rather than actual exposure and must be acknowledged as a limitation of the study design, and a separate study was used to assess the dominant emotion of the campaigns rather than a sub-sample of the main study.

A strength of our study is that it included multiple quit-related behaviours and antecedents, including thinking about quitting, quit intentions, and quit attempts, allowing an examination of the relative effects of different types of campaigns on a range of tobacco campaign endpoints. The study is sample weighted to represent the NSW population, thus increasing the generalisability of results.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Echoing a sentiment expressed by others, further research10 is needed internationally on similar campaigns to examine if findings differ or are consistent with these Australian findings. The emotion that a campaign evokes in smokers should be an important consideration in the design of future tobacco control campaigns and as suggested by our study utilising a mix of campaigns that evoke both positive and negative emotions depending on the purpose and target of the campaign is seen as critical in maintaining campaign effectiveness.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the idea of the study and to the interpretation of the results. BOH led the implementation of the study and wrote the first draft of the article, KO led the analysis and all authors reviewing and approving the final version.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dominic Lees, NSW Health Biostatistics Trainee, and former Research and Evaluation Officer, Cancer Institute NSW, Caroline Anderson, former Research and Evaluation Officer, Cancer Institute NSW and Sandra Rickards, Team Leader, Research and Evaluation, Cancer Institute NSW for their contribution to the research used in this study. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (project number: 2017/497).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data pertaining to the CITTs survey is publicly available here https://www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/data-research/cancer-related-data/request-unlinked-unit-record-data-for-research/cancer-institute-tobacco-tracking-survey-(citts)