Comparison of Long-Term Clinical Outcomes Between Spontaneous and Therapy-Induced HBsAg Seroclearance

Abstract

Background and Aims

HBsAg seroclearance is considered a realistic goal in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), known as “functional cure.” However, it remains elusive whether nucleos(t)ide analogue (NUC)-induced HBsAg seroclearance, compared with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance, differs in its association with favorable long-term clinical outcomes.

Approach and Results

A total of 1,972 CHB patients with confirmed HBsAg seroclearance at least two consecutive times, 6 months apart, were retrospectively analyzed. Risks of HCC development and composite clinical events, including HCC, liver-related death, and liver transplantation, were compared between spontaneous and NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance. Of 1,972 patients, mean patient age was 53.7 years, and 64.4% were men. Cirrhosis was present in 297 (15.1%) patients. HBsAg seroclearance was achieved spontaneously in 1,624 (82.4%) patients and by NUC treatment in 348 (17.6%). HCC developed in 49 patients, with an annual incidence of 0.38 of 100 person-years (PY) during a median follow-up of 5.6 years. With 336 propensity-score–matched pairs, risks of HCC (P = 0.52) and clinical events (P = 0.14) were not significantly different between NUC-induced and spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance. By multivariable analysis, NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, compared with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance, was not associated with the significantly higher risk of HCC (adjusted HR [AHR], 1.49; P = 0.26) and clinical events (AHR, 1.78; P = 0.06).

Conclusions

Risks of HCC and clinical events were not significantly different between spontaneous and NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance. Nonetheless, annual risk of HCC exceeds the recommended cutoff for HCC surveillance even after HBsAg seroclearance, suggesting that continued HCC surveillance is required.

Abbreviations

-

- AFP

-

- alpha-fetoprotein

-

- AHR

-

- adjusted HR

-

- AST

-

- aspartate aminotransferase

-

- APRI

-

- AST-to-platelet ratio index

-

- AUROC

-

- area under receiver operating characteristic

-

- CHB

-

- chronic hepatitis B

-

- FIB-4

-

- Fibrosis-4

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- LLOD

-

- lower limit of detection

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- NUC

-

- nucleos(t)ide analogue

-

- PS

-

- propensity score

-

- PY

-

- person-year

-

- THRI

-

- Toronto HCC Risk Index

Currently, professional societies and regulatory agencies regard establishing HBsAg seroclearance as a recommended treatment goal of chronic hepatitis B (CHB).(1-5) This is called “functional cure” and is characterized by the sustained seroclearance of HBsAg with or without HBsAb seroconversion.(4, 6)

HBsAg seroclearance rarely occurs in patients with CHB. Spontaneous HBsAg is an infrequent event with an annual rate of <1%.(7, 8) Rate of HBsAg seroclearance during treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NUCs) has been known to be as low as that of spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance.(9-15) However, once achieved, NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance is as durable as spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance(16) and is associated with improvements in liver histology and long-term clinical outcomes, including HCC and liver-related death.(14, 17-22) Nonetheless, it is not clear whether NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, compared with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance, is associated with different long-term clinical outcomes. Only a few observational studies reported this comparison as a part of subgroup analyses, which were limited owing to the small number of included patients and relatively short follow-up period.(16, 17, 23)

Currently, many therapeutics to aid in achieving this functional cure of CHB are under clinical development, and the rate of HBsAg seroclearance is expected to increase in the near future with the introduction of these therapies. Hence, long-term clinical outcomes after the achievement of HBsAg seroclearance by treatment, compared with HBsAg seroclearance through the course of natural history of CHB, should be evaluated in a large-scale cohort with a sufficient observational period. Therefore, we aimed to compare the long-term risks of HCC and clinical events between patients who achieved NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance and spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance.

Patients and Methods

Study Patients

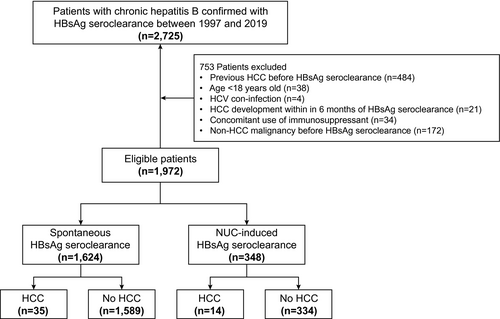

The source population for this study comprised 2,725 consecutive CHB patients with confirmed HBsAg seroclearance at least two consecutive times, 6 months apart, at Asan Medical Center, South Korea, between 1997 and 2019 (Fig. 1). Data were collected from the electronic medical records of the Asan Medical Center clinical database. All patients had serum HBsAg for at least 6 months before HBsAg seroclearance and were followed up for at least 6 months after HBsAg seroclearance. We excluded patients who met any of the following criteria: age <18 years old (n = 38); previous history of HCC before HBsAg seroclearance (n = 484); coinfection with HCV (n = 4); HCC development 6 months after HBsAg seroclearance (n = 21); concomitant use of immunosuppressant (n = 34); and non-HCC malignancy before HBsAg seroclearance (n = 172). Consequently, a total of 1,972 patients comprised the study population.

Routine laboratory tests were performed at the time of HBsAg seroclearance, and patients routinely underwent clinical examinations, liver function tests, HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBV DNA tests, and HCC surveillance with ultrasonography and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) every 6 months during follow-up.

The institutional review board of Asan Medical Center approved this study, and the requirement for informed consent was waived because this was a historical cohort study.

Clinical and Laboratory Variables

Cirrhosis was clinically defined as the presence of any of the following findings: coarse liver echotexture and nodular liver surface on ultrasonography; clinical features of portal hypertension (e.g., ascites, splenomegaly, or varices); or thrombocytopenia (<150,000/mm3).

Serum HBsAg was tested qualitatively (ARCHITECT assay; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL or immunoradiometric assay kit; DiaSorin, Vercelli, Italy) or quantitatively (ARCHITECT assay; lower limit of detection [LLOD], 0.05 IU/mL; Abbott Laboratories). HBsAg seroclearance, as described earlier, was defined as HBsAg negativity by at least two consecutive tests, 6 months apart, regardless of anti-HBs positivity. Anti-HBs seroconversion was defined as detection of anti-HBs antibody combined with HBsAg negativity. Serum HBV-DNA levels were measured using a Hybrid Capture assay (Digene Hybrid Capture II assay; LLOD, 20,000 IU/mL; Digene Diagnostics, Gaithersburg, MD) before 2007 and subsequently an RT-PCR assay (LLOD, 15 IU/mL; Abbott Laboratories). HBV genotype was not determined because ~98% of Korean patients with CHB have genotype C HBV.(24)

Primary Outcome and Assessment

The primary outcome of interest in the present study was HCC development after HBsAg seroclearance, and the secondary outcome was the development of a clinical event, which is a composite outcome, including HCC, liver-related death, and liver transplantation (LT). HCC diagnosis was based on histological examination or typical imaging findings on either dynamic CT or MR.(25, 26) Liver-related death was defined as any death attributable to complications of end-stage liver disease. Patients were followed up from the date of first confirmed HBsAg seroclearance to the date of HCC development, death, LT, or last follow-up (March 31, 2020), whichever came first. In addition, patients were evaluated using various HCC risk scores, including PAGE-B,(27) modified PAGE-B,(28) and the Toronto HCC Risk Index (THRI).(29) Scores originally developed for evaluating liver fibrosis, such as the aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI)(30) and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score,(31) were also calculated to evaluate the risk of HCC.

Predicted 5- and 10-year risks of developing HCC were estimated by PAGE-B score, and area under receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) was computed using a time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) method with a cut-off value of 9.

Statistical Analysis

All study patients who fulfilled the eligibility criteria at baseline were included in the analyses based on an intention-to-treat principle. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the chi-square test and t test, respectively.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of HCC and clinical event. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify predictive factors of long-term outcomes. The Poisson regression model was used to estimate annual rates of HCC and clinical event with CIs. The log-rank test was used to compare risk of HCC and clinical event between spontaneous and NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance. Propensity score (PS)-matched analysis was used to minimize potential confounding between spontaneous and NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance. PSs were computed using the following variables: age, sex, cirrhosis, AST, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, serum albumin, serum creatinine, prothrombin time, AFP, diabetes, PAGE-B, mPAGE-B, APRI, FIB-4, and THRI. Missing values, constituting 0.6% (creatinine) to 15.3% (AFP) of the baseline laboratory data, were imputed using linear interpolation by the MICE package. For PS matching, a nearest-neighbor 1:1 matching scheme with the caliper size of 0.1 was used. None of the standardized differences for any baseline covariates in the matches exceeded 0.2. Statistical inference was performed using the Cox regression models with robust standard errors and the sandwich covariance matrix estimation, which accounted the clustering of matched pairs.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (http://cran.r-project.org/). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 1,972 patients with CHB with confirmed HBsAg seroclearance were analyzed. Mean patient age was 53.7 years, and 64.4% of the patients were men (Table 1). Cirrhosis was present in 15.1% of the total population. Of the study patients, 1,624 (82.4%) achieved HBsAg seroclearance spontaneously, and 348 (17.6%) achieved NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance.

| Characteristics | Entire Cohort | PS-Matched Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n = 1,972) | Spontaneous HBsAg Seroclearance (n = 1,624) | NUC-Induced HBsAg Seroclearance (n = 348) | P Value | Spontaneous HBsAg Seroclearance (n = 336) | NUC-Induced HBsAg Seroclearance (n = 336) | SMD | |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 53.7 ± 11.2 | 54.2 ± 11.3 | 51.0 ± 10.4 | <0.001 | 50.9 ± 11.2 | 51.2 ± 10.4 | 0.02 |

| Men, n (%) | 1,270 (64.4) | 1.025 (63.1) | 245 (70.4) | 0.012 | 228 (67.9) | 234 (69.6) | 0.08 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 297 (15.1) | 188 (11.6) | 109 (31.3) | <0.001 | 107 (31.8) | 97 (28.9) | 0.03 |

| AST, IU/L | 24 [20-30] | 24 [20-30] | 24 [20-28] | 0.05 | 24 [20-29] | 24 [20-28] | 0.02 |

| ALT, IU/L | 19 [14-28] | 20 [14-28] | 18 [13-27] | 0.04 | 20 [14-27] | 18 [13-28] | 0.08 |

| ALP, IU/L | 65 [53-79] | 65 [54-80] | 63 [53-77] | 0.22 | 63 [52-78] | 63 [53-78] | 0.06 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.2 [4.0-4.4] | 4.2 [4.0-4.4] | 4.2 [4.0-4.4] | 0.13 | 4.2 [4.0-4.4] | 4.2 [4.0-4.4] | 0.07 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.9 [0.7-1.2] | 0.9 [0.7-1.2] | 0.9 [0.7-1.2] | 0.02 | 1.0 [0.7-1.3] | 0.9 [0.7-1.2] | 0.01 |

| Prothrombin time, INR | 1.0 [1.0-1.1] | 1.0 [1.0-1.1] | 1.0 [1.0-1.1] | 0.01 | 1.0 [1.0-1.1] | 1.0 [1.0-1.1] | 0.01 |

| Platelets, 1,000/mm3 | 193 [158-230] | 197 [163-233] | 174 [138-212] | <0.001 | 183 [141-223] | 176 [140-215] | 0.02 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 [0.7-1.0] | 0.9 [0.7-1.2] | 0.9 [0.7-1.0] | 0.68 | 0.9 [0.7-1.0] | 0.9 [0.7-1.0] | 0.01 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 1.8 [1.2-2.6] | 1.8 [1.2-2.6] | 1.7 [1.2-2.6] | 0.96 | 1.8 [1.2-2.6] | 1.7 [1.2-2.6] | 0.06 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 169 (8.6) | 145 (8.9) | 24 (6.9) | 0.26 | 20 (6.0) | 24 (7.1) | 0.01 |

| NUC used, n (%) | NA | ||||||

| Lamivudine | 220 (63.2) | — | 220 (63.2) | ||||

| Entecavir | 74 (21.3) | — | 74 (21.3) | ||||

| TDF | 46 (13.2) | — | 46 (13.2) | ||||

| Telbivudine | 4 (1.1) | — | 4 (1.1) | ||||

| Clevudine | 4 (1.1) | — | 4 (1.1) | ||||

| HCC risk scores | |||||||

| PAGE-B | 12 [10-18] | 12 [12-17] | 14 [10-18] | 0.002 | 14 [10-18] | 14 [10-18] | 0.01 |

| Modified PAGE-B | 11 [9-13] | 11 [9-13] | 11 [9-13] | 0.89 | 11 [9-13] | 11 [9-13] | 0.03 |

| THRI | 227 [177-267] | 227 [177-267] | 227 [177-277] | 0.06 | 227 [177-277] | 227 [177-277] | 0.04 |

| Liver fibrosis scores | |||||||

| APRI | 0.3 [0.2-0.4] | 0.3 [0.2-0.4] | 0.3 [0.3-0.5] | 0.002 | 0.3 [0.3-0.5] | 0.3 [0.3-0.5] | 0.02 |

| FIB-4 index | 1.5 [1.1-2.1] | 1.5 [1.1-2.1] | 1.6 [1.2-2.5] | 0.034 | 1.5 [1.1-2.4] | 1.6 [1.1-2.3] | 0.07 |

| Duration of follow-up, years | 5.6 [2.9-9.5] | 5.6 [2.8-9.6] | 4.6 [2.4-7.8] | <0.001 | 5.6 [2.7-9.0] | 4.6 [2.3-7.8] | 0.27 |

- Presented as median [IQR].

- Abbreviations: INR, international normalized ratio; NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized difference of the mean; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Compared with patients achieving spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance, those achieving NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance were younger (54.2 vs. 51.0 years), more likely to be male (63.1% vs. 70.4%), and more likely to have cirrhosis (11.6% vs. 31.3%; Table 1). Among 348 patients with NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, lamivudine was the most-used treatment regimen (63.2%), followed by entecavir (21.3%), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (13.2%), telbivudine (1.1%), and clevudine (1.1%), at the time of HBsAg seroclearance.

Development of Clinical Outcome

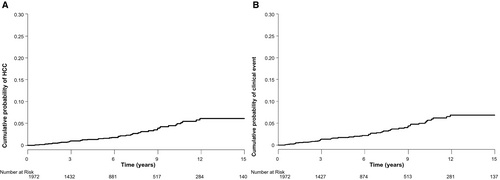

Of the 1,972 patients with 12,890 person-years (PY) of observation, 49 developed HCC with an annual incidence of 0.38 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.28-0.50) during a median follow-up duration of 5.6 years (interquartile range [IQR], 2.7-9.2). The 3-, 5-, 10-, and 15-year cumulative HCC incidences in the Kaplan-Meier analysis were 1.0%, 1.5%, 4.5%, and 6.1%, respectively (Fig. 2A). HCC occurred from 6 months to 11.9 years after HBsAg seroclearance. Rate of HCC development did not decrease over time after HBsAg seroclearance. Except for the first year after HBsAg seroclearance, annual rate of HCC was maintained above 0.2% per year for the remaining 11 years after HBsAg seroclearance, and the serial trend of HCC development appeared to slowly increase during the study period (Supporting Fig. S1). However, because we excluded patients who developed HCC within 6 months after HBsAg seroclearance, actual incidence of HCC in the first year after HBsAg seroclearance may have been underestimated.

During 12,819 PY of observation, 57 patients developed clinical events with an annual incidence of 0.44 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.34-0.58). The 3-, 5-, 10-, and 15-year cumulative incidences of clinical events were 1.3%, 1.9%, 5.0%, and 6.8%, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Of 57 clinical events, 49 were HCC and 8 LT. All 8 patients (6 men and 2 women) who received LT had cirrhosis. No liver-related death was observed during the study period: 10 patients died because of non-liver-related causes, 8 because of non-liver-origin cancer, 1 because of coronary artery disease, and 1 because of congestive heart failure.

Comparison of HCC Development and Clinical Events in a PS-Matched Cohort

A total of 35 patients with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance developed HCC with an annual HCC incidence of 0.32 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.22-0.44), whereas 14 patients with NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance developed HCC with an annual HCC incidence of 0.73 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.40-1.23; Table 2).

| Group | No. of Patients | PY | No. of Events | Rate, per 100 PY (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC | ||||||

| Entire cohorts | 1,972 | 12,890 | 49 | 0.38 (0.28-0.50) | ||

| Spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance | 1,624 | 10,981 | 35 | 0.32 (0.22-0.44) | Reference | |

| NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance | 348 | 1,909 | 14 | 0.73 (0.40-1.23) | 1.48 (0.76-2.88) | 0.26 |

| PS-matched cohorts | ||||||

| Spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance | 336 | 2,227 | 11 | 0.49 (0.25-0.88) | Reference | |

| NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance | 336 | 1,841 | 12 | 0.65 (0.34-1.14) | 1.31 (0.58-2.96) | 0.52 |

| Clinical event (HCC, liver-related death, or LT) | ||||||

| Entire cohorts | 1,972 | 12,819 | 57 | 0.44 (0.34-0.58) | ||

| Spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance | 1,624 | 10,969 | 37 | 0.34 (0.24-0.46) | Reference | |

| NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance | 348 | 1,850 | 20 | 1.08 (0.66-1.67) | 1.78 (0.98-3.22) | 0.06 |

| PS-matched cohorts | ||||||

| Spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance | 336 | 2,223 | 12 | 0.54 (0.28-0.94) | Reference | |

| NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance | 336 | 1,796 | 17 | 0.95 (0.55-1.51) | 1.73 (0.82-3.63) | 0.14 |

- * By multivariable Cox regression analysis for the entire cohort.

For fair comparison as well as minimizing confounders affecting the risk of HCC between spontaneous and NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, 336 PS-matched pairs were generated. Baseline characteristics between these two groups are presented in Table 1. After PS matching, all baseline covariates were well balanced and did not exceed 0.1 of the standardized mean difference (Table 1).

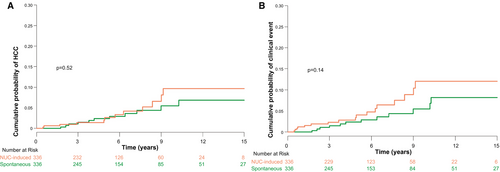

In the PS-matched pairs, annual HCC incidence was 0.49 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.25-0.88) in patients with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance and 0.65 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.34-1.14) in those with NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, without any significant difference between the two groups (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.58-2.96; P = 0.52; Table 2; Fig. 3A).

Of 336 PS-matched pairs, annual incidences of clinical events were 0.54 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.28-0.94) after spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance and 0.95 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.55-1.51) after NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, without any significant difference between the two groups (HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 0.82-3.63; P = 0.14; Table 2; Fig. 3B).

Predictive Factors for the Development of HCC and Clinical Events

By multivariable Cox regression analysis, NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, compared with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance, was not an independent factor for the development of HCC (adjusted HR [AHR], 1.48; 95% CI, 0.76-2.88; P = 0.26) and clinical events (AHR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.98-3.22; P = 0.06). Older age, male sex, and presence of cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance were significant predictive factors that were associated with a higher risk of HCC development and clinical events (Table 3).

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | AHR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| HCC* | ||||||

| HBsAg seroclearance | ||||||

| Spontaneous | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| NUC induced | 2.38 | 1.27-4.43 | 0.006 | 1.48 | 0.76-2.88 | 0.26 |

| Age, per 1-year increase | 1.05 | 1.02-1.08 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.03-1.09 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 8.84 | 2.75-28.44 | <0.001 | 8.10 | 2.51-26.18 | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis, present | 8.26 | 4.68-14.57 | <0.001 | 5.45 | 2.68-11.08 | <0.001 |

| Albumin, per 1-g/L increase | 0.55 | 0.32-0.95 | 0.33 | |||

| Total bilirubin | 1.11 | 1.03-1.19 | 0.005 | 0.99 | 0.91-1.09 | 0.88 |

| Prothrombin time, INR | 1.65 | 0.88-3.06 | 0.12 | |||

| Platelets, 1,000/mm3 | 0.99 | 0.98-0.99 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.16 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.12 | 0.97-1.29 | 0.11 | |||

| AFP, ng/mL | 1.00 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.71 | |||

| Diabetes, present | 0.69 | 0.21-2.22 | 0.54 | |||

| Anti-HBs seroconversion | 0.68 | 0.38-1.21 | 0.19 | |||

| Clinical event† | ||||||

| HBsAg seroclearance | ||||||

| Spontaneous | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| NUC induced | 3.27 | 1.89-5.65 | <0.001 | 1.78 | 0.98-3.22 | 0.06 |

| Age, per 1-year increase | 1.03 | 1.02-1.06 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 1.01-1.07 | 0.01 |

| Sex, male | 6.02 | 2.40-15.07 | <0.001 | 5.26 | 2.09-13.20 | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis, present | 9.43 | 5.56-16.01 | <0.001 | 4.79 | 2.48-9.26 | <0.001 |

| Albumin, per 1-g/L increase | 0.39 | 0.25-0.60 | <0.001 | |||

| Total bilirubin | 1.12 | 1.05-1.19 | 0.001 | |||

| Prothrombin time, INR | 3.47 | 2.36-5.10 | <0.001 | 2.24 | 1.16-4.30 | 0.02 |

| Platelets, 1,000/mm3 | 0.99 | 0.98-0.99 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.01 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.17 | 1.05-1.29 | <0.001 | |||

| AFP, ng/mL | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.06 |

| Diabetes, present | 1.02 | 0.41-2.55 | 0.97 | |||

| Anti-HBs seroconversion | 0.75 | 0.44-1.28 | 0.29 | |||

- * Total number of patients, 1,972; number of events, 49.

- † Total number of patients, 1,972; number of events, 57.

- Abbreviation: INR, international normalized ratio.

Durability of HBsAg Seroclearance

HBsAg reversion after seroclearance occurred in 39 patients (2.0%) during the study period (20 of 1,624 [1.2%] patients in the spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance group and 19 of 348 [5.5%] patients in the NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance group). Cumulative rates of HBsAg reversion at 3, 5, and 10 years were 1.6%, 1.8%, and 2.4%, respectively. Of the 39 seroreverted patients, 35 (89.7%) achieved spontaneous reclearance of HBsAg without retreatment. The remaining 4 patients were still positive for HBsAg at the last follow-up.

Anti-HBs Seroconversion

Cumulative rates of anti-HBs seroconversion in the entire cohort at 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, and 15 years after HBsAg seroclearance were 37.0%, 50.3%, 60.4%, 72.4%, 85.3%, and 91.9%, respectively, by the Kaplan-Meier analysis (Supporting Fig. S2). Patients with NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance were significantly more likely to achieve anti-HBs seroconversion than those with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance in the entire cohort (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.51; P < 0.001; Supporting Fig. S3) and in the PS-matched cohort (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.09-1.58; P = 0.005; Supporting Fig. S4).

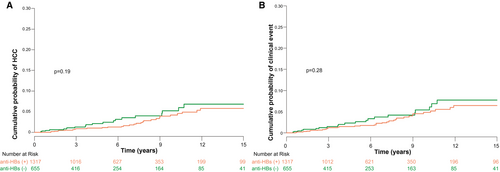

Risk of HCC (P = 0.19; Fig. 4A) and clinical events (P = 0.28; Fig. 4B) did not differ between patients achieving anti-HBs seroconversion and those not achieving anti-HBs seroconversion.

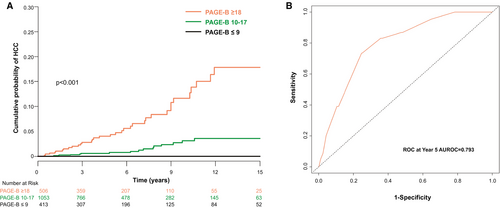

HCC Prediction After HBsAg Seroclearance

PAGE-B score was used to evaluate risk of HCC development for the entire cohort. Based on the suggested PAGE-B cut-off values, 413 (20.9%), 1,053 (53.4%), and 506 (25.7%) patients were categorized into the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups, respectively. The 5-year cumulative incidences of HCC in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups were 0.00, 0.22, and 1.11 per 100 PY, respectively (Fig. 5A). AUROCs for PAGE-B score as a predictor of HCC development were 0.793 (95% CI, 0.713-0.872) at 5 years and 0.769 (95% CI, 0.699-0.838) at 10 years (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

In the present study, no significant difference in risk of HCC and clinical events was observed between patients who achieved spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance and those who achieved NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance. However, risk of HCC persisted even after HBsAg seroclearance during up to 10 years. Indeed, the annual incidence rate of HCC was beyond the cost-effectiveness limit of HCC surveillance (0.2%) recommended by the current international guidelines.(32) Older age, male sex, and presence of cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance were predictive factors for the development of HCC and clinical events after HBsAg seroclearance. The achievement of anti-HBs seroconversion did not affect long-term clinical outcomes once HBsAg seroclearance was achieved.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study included the largest number of patients achieving NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance and evaluated clinical outcomes over the longest reported follow-up period.

Spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance mainly occurred in patients with inactive CHB being regarded favorable expected outcomes. The present study suggests that HBsAg seroclearance achieved by NUC treatment, which was initiated at the active hepatitis phase, can show a comparable risk of long-term clinical outcomes with that of spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance. Therefore, our findings reaffirm that functional cure is a realistic goal for CHB treatment. In this regard, HBsAg seroclearance can act as a desirable end-point in phase 3 and possibly phase 2b clinical trials of newly developed CHB treatment. Notably, 8 patients received LT without HCC development during the study period. All these patients had already developed cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance and underwent transplantation because of decompensated cirrhosis. This implies that if cirrhosis has already developed at the time of HBsAg seroclearance, the risk of adverse events from cirrhosis may persist after HBsAg seroclearance, although additional insult from necroinflammation by active HBV infection can be abolished. In other words, treatment with more recent therapies for CHB should be initiated as early as possible before cirrhosis develops. These results are in line with previous studies reporting that HBsAg seroclearance cannot completely abolish the risk of HCC, especially in patients aged >50 years or those with established cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance.(23, 33)

It is well accepted that risk of HCC declines once HBsAg seroclearance is achieved, compared with the persistence of HBsAg positivity.(14, 15) Nevertheless, our group previously suggested the need for continued HCC surveillance in patients achieving HBsAg seroclearance if they were males aged >50 years, considering their observed annual risk of HCC >0.2%.(23) In keeping with previous findings, overall annual incidences of HCC in the present study were 0.21% per year in patients without cirrhosis and 1.58% per year in those with cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance. Currently, there is no clear recommendation for HCC surveillance in patients after HBsAg seroclearance owing to insufficient evidence.(26, 32) Given that surveillance for HCC is cost-effective when the annual rate of HCC exceeds 0.2% in patients without cirrhosis with CHB and 1.5% in patients with cirrhosis,(32) patients included in the present study surpass these cutoffs of HCC surveillance, indicating the necessity of continued HCC surveillance even after HBsAg seroclearance. Notably, rate of HCC development slowly increases with time after HBsAg seroclearance. A possible explanation for this is that patients get older with time after HBsAg seroclearance, resulting in an increase in risk of HCC, because older age is one of the strongest risk factors for HCC development in patients with CHB.(23) Moreover, oncogenic potential from integration of the HBV genome into the human hepatocyte chromosomes does not ameliorate, regardless of HBsAg seroclearance.(34)

However, whether all patients with HBsAg seroclearance require continued HCC surveillance remains unanswered. Of 49 patients with HCC development, only 3 female patients developed HCC, and they were >50 years (median, 61.3). No female patient aged <50 years developed HCC during the study period, which was consistent with previous reports.(23, 33) Among 46 male patients who developed HCC, only 4 developed HCC aged <50 years, 3 of whom had cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance. Therefore, a female patient aged <50 years may be carefully considered to be exempted from HCC surveillance after HBsAg seroclearance. PAGE-B score was still predictive of HCC development in patients with HBsAg seroclearance, with an AUROC of 0.793. Compared with a previous report, the AUROC in this study was lower, which might stem from additional HCC risk reduction attributable to HBsAg seroclearance, leading to a result lower than the estimated risk of HCC based on the PAGE-B model.(27) Patients in the low-risk group with a PAGE-B score of ≤9 at the time of HBsAg seroclearance remained free of HCC at 3, 5, and 10 years after HBsAg seroclearance. Thus, the negative predictive value of PAGE-B score was 100% for this group. Although patients with cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance should continue to undergo regular surveillance for HCC, decisions regarding surveillance for those without cirrhosis can be guided by the PAGE-B score. For example, patients with a low PAGE-B score and no cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance may be exempted from surveillance for HCC.

The question to be answered regarding HBV functional cure is whether anti-HBs seroconversion should be required.(6) From the virological standpoint, anti-HBs seroconversion may not be sufficient to sustain durable HBsAg seroclearance.(6) However, the impact of anti-HBs seroconversion on clinical outcomes remains open for research. In the present study, anti-HBs seroconversion was not associated with the development of HCC and clinical events. This suggests that anti-HBs seroconversion is not mandatory to achieve HBV functional cure. In this regard, the current definition of HBV functional cure, which is a sustained HBsAg seroclearance with and without anti-HBs seroconversion, could be justified.

The strength of the present study is its large sample size with a long follow-up duration enabling the observation of rarely developed clinical outcomes with sophisticated statistical analysis. We also defined HBsAg seroclearance as HBsAg negativity at least two consecutive times, 6 months apart, which is a proposed definition of HBsAg seroclearance for future phase 3 trials for the CHB cure program.(6)

This study has several limitations. First, because of the nature of a historical cohort study, some biases are unavoidable. For example, unlike prospective studies, patients were not supposed to be followed up regularly, and some patients missed regular surveillance for HCC against advice. However, the evaluation of these rare outcomes among this rare patient group requires a large number of patients and a long-term follow-up period. Therefore, conducting a prospective study for this aim might be not feasible. Second, this study represents long-term outcomes in patients infected by HBV genotype C. Because almost all Korean patients with CHB are infected by genotype C, the findings of this study should be further evaluated in patients infected by a different genotype of HBV. Third, our study results may not be applicable for patients treated with prospective antiviral drugs with different modes of action that would be introduced in the near future. Fourth, of the 348 patients who achieved NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance, 27 (7.8%) had a history of previous interferon therapy. However, the median time interval from the last dose of interferon to the point of HBsAg seroclearance was 11.4 years (IQR, 7.4-14.4). Thus, we considered that the impact of previous interferon therapy on the achievement of HBsAg seroclearance was negligible. Fifth, our finding was derived from qualitative HBsAg seroclearance by NUC treatment, which has been widely used in the past decades. Thus, whether potential developed quantitative tests for HBsAg and upcoming agents for treatment for CHB reproduce our finding should be further evaluated in the future. Last, because of the small number of HCC and clinical events, there is a possibility that our study had insufficient power.

In conclusion, in a large cohort comprising patients who achieved HBsAg seroclearance, there appeared to be a similar risk of HCC and clinical events between spontaneous and NUC-induced HBsAg seroclearance. Although the incidence of HCC and clinical events was low, annual risk of HCC exceeded the currently recommended cutoff for HCC surveillance, even after HBsAg seroclearance. Older age, male sex, and presence of cirrhosis at the time of HBsAg seroclearance were significantly associated with a higher risk of HCC and clinical events.

Author Contributions

All authors have full access to all data used in the study and take responsibility for integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. J.C., S.Y., and Y-S.L. were responsible for conception and design of the study; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting of the manuscript. J.C. performed statistical analyses. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.