Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents and young adults: The next frontier in the epidemic

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a significant health burden in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) which has substantially risen in prevalence over the last decades. The occurrence of NAFLD parallels high rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome in this age group, with unhealthy lifestyle also playing an independent role. Genetic factors, sex, and ethnicity should be considered in a risk stratification model. NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in AYAs often go unrecognized and, if untreated, can progress eventually to cirrhosis requiring liver transplantation (LT) before the age of 40. Recently, NASH has increased as an indication for LT in this age group. Important knowledge gaps include the feasibility of noninvasive diagnostic tests and imaging modalities as well as uncertainty about unique histological features and their predictive value. Future clinical trials focused on AYAs are needed to determine effectiveness of therapies. Tools for increasing awareness and prevention of NAFLD in AYAs are greatly needed. (Hepatology 2017;65:2100-2109).

Abbreviations

-

- AF

-

- advanced fibrosis

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- AST

-

- aspartate aminotransferase

-

- AUROC

-

- area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

-

- AYA

-

- adolescent and young adult

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CAP

-

- controlled attenuation parameter

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- CK-18

-

- cytokeratin-18

-

- CLD

-

- chronic liver disease

-

- ED

-

- erectile dysfunction

-

- FIB-4

-

- fibrosis index with 4 components

-

- GD

-

- gestational diabetes

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HS

-

- hepatic steatosis

-

- LF

-

- liver fibrosis

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- NAFLD

-

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

-

- NAS

-

- NAFLD activity score

-

- NASH

-

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

-

- NFS

-

- NAFLD fibrosis score

-

- NHANES

-

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- PCOS

-

- polycystic ovary syndrome

-

- SS

-

- simple steatosis

-

- T2DM

-

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

-

- USG

-

- ultrasonography

-

- VCTE

-

- vibration controlled transient elastography

The term adolescents and young adults (AYAs) characterizes a population of patients beginning at age 15 with disputable cutoffs at 24, 29, and 39 years of age.1 Within this group, adolescence is defined as between 15 and 19 years of age with young adulthood starting at the age of 20 years. This term is widely used by our oncology colleagues who have recognized over the past decade that AYAs with cancer have different needs and treatment challenges than both younger children and older adults.2 Some of these challenges include inadequate health insurance coverage in young adults, delays in diagnosis attributed to their sense of invulnerability and lack of awareness among physicians, the exclusion or low referral rates of AYAs to clinical trials, compromised fertility, and issues with transitioning care between pediatric and adult providers. The broader age range of 15-39 years has been widely accepted as the definition of AYAs in the cancer literature and will be used in this review.

Risk factors associated with major chronic liver disease (CLD) in the United States start or become established in subjects in the AYA age group, including obesity for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcohol consumption for alcoholic liver disease, and intravenous drug use for hepatitis C infection. This may lead to a silent epidemic of CLD that affects AYAs in the United States. The aim of this review is to introduce the term AYA to the hepatology community in order to raise awareness of unique aspects of liver disease in this age group with specific focus on NAFLD, the most common CLD in both children and adults in the United States.3 Among some of the most important risk factors for NAFLD in AYAs are: high prevalence of obesity4, 5; unhealthy eating habits; and sedentary lifestyle.6 Frequent mood disturbances and significant alcohol use might also contribute to disease progression.7 The interplay between these factors in the setting of genetic predisposition can lead to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can result in cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at a younger age than commonly recognized.

Epidemiology

Data on prevalence of NAFLD in AYAs are mainly based on epidemiological studies that have variously used elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as a surrogate marker for NAFLD, ultrasonography (USG), or liver biopsies performed in severely obese adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery. Accordingly, study results vary greatly depending on the study population and applied methodology.

A recent cross-sectional analysis, based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, assessed NAFLD prevalence in subjects aged 18-35 years.8 NAFLD was defined as elevated ALT (>30 U/L for males and >19 U/L for females) in subjects with body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2 and lack of other etiologies for CLD. The study demonstrated that NAFLD in young adults has risen almost 2.5 times over three decades (9.6% in 1988-1994 to 24% in 2005-2010) and more than one half of morbidly obese young adults had NAFLD (57.4%). Another study, applying the same methodology in adolescents, noted similar results (a rise in NAFLD prevalence from 3.9% in 1988-1994 to 10.7% in 2007-2010).9 On multivariate analysis, both studies showed identical risk factors for NAFLD in AYAs: older age; male sex; and Hispanic ethnicity.8, 9 The main limitation of using elevated ALT, however, is that it correlates poorly with presence and severity of NAFLD, and normal ALT can be observed in subjects with NASH and advanced fibrosis (AF).

Another study using NHANES data from 1988-1994 defined NAFLD as hepatic steatosis (HS) on USG in the absence of significant alcohol intake.10 When stratified by age, prevalence of NAFLD was 7.4% in men and 7.9% in women in the age group <30 years, whereas in the cohort of 30-40 years of age, prevalence increased to 13.3% and 10.0%, respectively. This increased prevalence with older age was also observed in the seminal study that reviewed liver histology of 742 children and found 0.7% NAFLD prevalence in toddlers increasing to 17.3% in teenagers of 15-19 years.11 Two other studies used ultrasound to evaluate NAFLD prevalence in adolescents.12, 13 The discordant results between these two ultrasound studies (2.5%13 vs. 12.8%12) may be explained by different definitions of steatosis used. In the first study, increased liver echogenicity was interpreted as present, absent, or uncertain,13 whereas in the second study, the researchers used a composite scoring system that included three main components: liver echotexture; deep attenuation; and vessel blurring.12

Prevalence of NAFLD in severely obese adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery is 59%-83%.14-16 The largest study, Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS), was a prospective multicenter analysis of 148 patients who underwent intraoperative liver biopsy between 2007 and 2012.16 This study reported a NAFLD prevalence of 59% in these teenagers, with 34.5% having borderline or definite NASH. The majority of the patients had no fibrosis (81%); mild fibrosis (F ≤ 2) was noted in 18% of the patients, while only 1 patient had stage 3 fibrosis.

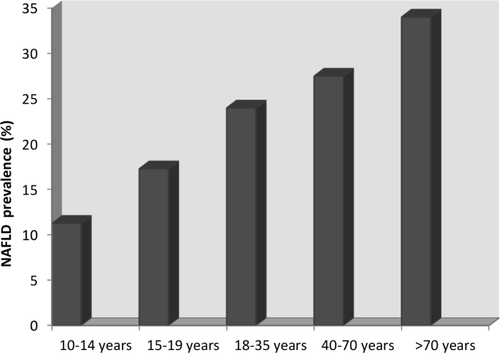

Table 1 summarizes data on prevalence of NAFLD in AYAs globally (Table 1), and Fig. 1 represents data on prevalence of NAFLD in AYAs compared to children11 and pooled prevalence in adults in the United States17 (Fig. 1).

| Study/Country | Study Methods and Age Range | No. of Participants | Study Period(s) | Prevalence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Schwimmer et al.,12 2006 USA |

Retrospective, autopsy review, 2-19 years |

742 (72% male, 34% Hispanic) |

1993-2003 |

9.6% overall, 17.3% for ages 15-19 years |

NAFLD in obese 38% |

|

Ayonrinde et al.,13 2011 Australia |

Cross-sectional,liver ultrasound,mean age 17 years |

1,170 (51% male) |

2006-2009 | 12.8% | NAFLD in females 16.3% vs. males 10.1% |

|

Welsh et al.,10 2013 USA |

NHANES, elevated ALT+BMI >85th percentile, 12-19 years |

12,714 (52% male; increased % of Mexican Americans and obesity over study periods) |

1988-1994 1999-2002 2003-2006 2007-2010 |

3.9% 9.1% 10.4% 10.7% |

Rise in obese females 13.0%-27.0%; obese males 29.5%-48.3% |

|

Lawlor et al.,14 2014 UK |

Cross-sectional,liver ultrasound,mean age 17.9 years |

1,711 (59% female) |

2008-2010 | 2.5% |

NAFLD in normal weight 0.4%, overweight 4.3%, obese 22.2%; similar in males and females |

|

Ayonrinde et al.,21 2015 Australia |

Cross-sectional,liver ultrasound,mean age 17 years |

1,167 | 2006-2009 | 15.2% | NAFLD in females 19.6% vs. males 10.8% |

|

Mrad et al.,9 2016 USA |

NHANES,elevated ALT+BMI ≥25 kg/m2, 18-35 years |

14,371 |

1988-1994 1994-2004 2005-2010 |

9.6% 24.0% |

2005-2010 35.3% prevalence in Mexican Americans; 57.4% in subjects with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 |

| NAFLD prevalence in morbidly obese adolescents | |||||

|

Xanthakos et al.,15 2006 USA |

Cross-sectional,liver biopsy in morbidly obese adolescents (mean BMI, 59 kg/m2), 13-19 years |

41 (61% female; 83% white) |

2003-2005 | 83.0% | Of the entire cohort, 20% had NASH and 29% had mild fibrosis (F ≤ 2) |

|

Corey et al.,16 2014 USA |

Retrospective,liver biopsy in morbidly obese adolescents (mean BMI, 53 kg/m2), 15-22 years |

27 (82% female, 26% Hispanic) |

2006-2012 | 66.7% | Of those with NAFLD, 37.0% had NASH, 40.7% had any fibrosis |

|

Xanthakos et al.,17 2015 USA |

Multicenter, prospective,liver biopsy in morbidly obese adolescents (median BMI, 52 kg/m2), 15-18 years |

148 (72% female, 9% Hispanic) |

2007-2012 | 59.0% | Of those with NAFLD, 24% had borderline and 10% had definite NASH, mild fibrosis (F ≤ 2) in 18%, F3 in 0.7%, no cirrhosis |

Risk Factors

OBESITY

Prevalence of obesity remains high, affecting 34.3% of young adults (aged 20-39 years),4 20.6% of adolescents (aged 12-19 years), and 17.4% of children aged 6-11 years,5 based on 2013-2014 NHANES data. Furthermore, 4%-6% of all youth in the United States have severe obesity and gain weight faster than any other subgroup.18 The importance of these facts is highlighted by studies that demonstrated that obese adolescents are more likely to develop severe obesity by the time they reach their early thirties19; childhood adiposity is associated with NAFLD in adolescence20; and weight gain in childhood correlates with the entire histological and clinical spectrum of adult NAFLD regardless of initial or attained BMI.21 A recent large cohort study demonstrated that overweight adolescents (aged 18-20 years) have an increased risk of severe liver disease (hazard ratio, 1.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16-2.32; P = 0.006) compared to those with normal BMI after a follow-up of 39 years.22 Each unit increase in BMI carried a 5% higher risk for development of severe liver disease.

TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increasingly diagnosed in the younger population. Most of the adolescents affected by T2DM are obese; peak onset is in puberty; and it occurs more commonly in females.23 One retrospective analysis showed that 48% of obese adolescents with T2DM had elevated ALT.24 Another cross-sectional study demonstrated that the risk for elevated ALT was almost doubled if T2DM was diagnosed before the age of 40 years (adjusted prevalence ratio, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.15-3.33).25 Conversely, magnetic resonance imaging–quantified hepatic fat in obese adolescents was associated with prediabetic phenotype, independent of total body fat, and is suggested as a strong risk factor for T2DM in this population.26

ALCOHOL

Although alcohol consumption in AYAs has declined over the last decades, it remains an important health burden in this age group.27 Binge drinking, defined as five or more alcoholic drinks in a row, is the most common pattern of drinking in adolescents and young adults aged 18-25 years.27 This pattern of alcohol consumption places AYAs at much higher risk for advanced forms of NAFLD later in life given that significant fibrosis progression was noted over a follow-up period of almost 14 years in subjects with established NAFLD who report heavy episodic drinking.28 Furthermore, any lifetime alcohol use in patients with NASH was shown to increase HCC risk 3.6 times (95% CI, 1.5-8.3; P = 0.003).29

SMOKING

Young adults (aged 25-44 years) have the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking among all age groups in the United States.30 Moreover, two thirds of adults who had ever smoked daily started doing so before the age of 18 years. The possible consequences of smoking for NAFLD progression have been demonstrated in a large cohort of adults with biopsy-proven NAFLD, where significant association between history of smoking and liver fibrosis (LF) was noted.31

LIFESTYLE

The unhealthy lifestyle of AYAs includes skipping meals, higher intake of fast food and energy-dense snacks, significant use of sugar-sweetened beverages, and physical inactivity. A longitudinal Australian study32 showed that this “Western diet” was associated with NAFLD, but the association was attenuated after adjusting for baseline BMI, suggesting that obesity is the leading pathogenic mechanism. Healthy diet reduced the risk of NAFLD (odds ratio [OR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.96; P = 0.033) in adolescents with central obesity at the time of follow-up. Another cross-sectional study in overweight and obese adolescents (mean age of 15.4 years) evaluated the effect of sugar and fat intake as determinants of HS and visceral obesity.33 High-fat diet, defined as >35% of daily energy intake from fat, increased the risk of having NAFLD by 12-fold. On the other hand, increased total sugar intake, soda consumption, and low fiber were positively associated with visceral adiposity, but not NAFLD. Despite several studies on adverse metabolic effects of fructose, a recent meta-analysis did not confirm an independent risk for NAFLD.34

SEX AND ETHNICITY

Sexual maturation has been associated with increased total body fat and subcutaneous adipose tissue in females, whereas males tend to deposit more visceral adipose tissue in the abdominal region, a difference that becomes more marked in young adulthood. Visceral fat was noted to be an independent predictor of degree of necroinflammation and stage of fibrosis in NAFLD,35 thus explaining sex differences of NAFLD prevalence in AYAs. Most studies report male sex as a risk factor for NAFLD in AYAs8, 9 and numerically higher prevalence in pubertal and postpubertal male adolescents than in females.11, 36 One exception is an Australian cohort where higher NAFLD prevalence in female adolescents was observed.12 Independent of body fat changes, physiological reduction of insulin sensitivity and decreased adiponectin levels during puberty might also play roles in the development of NAFLD.37 Physiological pubertal alterations and sex hormones production were suggested as the main pathogenic mechanism for changing histological features of NAFLD (pediatric vs. adult type) when subjects pre-, during, and post-puberty were compared.38

In the United States, both pediatric and adult studies have consistently reported highest NAFLD prevalence in Hispanics and lowest in African Americans.11, 39 NAFLD prevalence was also highest among Hispanic young adults of Mexican descent (35.3%).8 Potential underlying mechanisms for these ethnic disparities include different body fat distribution, genetic predisposition, and diet, among many other factors. Genetic risk was demonstrated in a study showing that the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 I148M variant manifested early in life of Hispanic children and adolescents and was associated with higher liver fat and lower levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.40

Reproductive Health and NAFLD

Recent evidence suggests that NAFLD may be associated with compromised reproductive health in both women and men, an issue of utmost importance in the AYA age group.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women during reproductive life. Prevalence of NAFLD in women with PCOS is 41%-55%.41, 42 Androgen level in girls with coexisting NAFLD was not significantly higher than that in girls with PCOS alone,43 despite previous reports suggesting high androgen levels as an independent risk factor for NAFLD.44 Women with NAFLD at reproductive age may benefit from screening for PCOS, given that 10 of 14 female patients with NAFLD were diagnosed with PCOS in a small study.45 Half of those patients had NASH on liver biopsy.

A Swedish population-based registry46 showed that women with preexisting NAFLD had a greater risk of gestational diabetes (GD), preeclampsia, Cesarean section, low preterm weight, and preterm birth. The results of this study should be interpreted with caution given that only 110 women had NAFLD in a cohort of almost 2 million women. A large, prospective study also demonstrated NAFLD, diagnosed by ultrasound during the first trimester of pregnancy, increases the risk of GD and dysglycemia in mid-pregnancy (adjusted OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1-4.3).47

Studies demonstrated lower testosterone levels and reduced sperm count and motility in men with HS when compared to healthy controls.48, 49 An association has been also noted between NASH and erectile dysfunction (ED) in a prospective pilot study of middle-aged men with biopsy-proven NAFLD, where NAFLD activity score (NAS) was the only independent predictor of ED.50

Natural History of NAFLD in AYAs

Currently, there are no longitudinal studies focusing on NAFLD progression in young adults. Data are also scarce in adolescents. In two studies, children aged 13-14 years had follow-up liver biopsies over a mean of 2851 and 41 months52 without any treatment in the meantime other than standard weight loss counseling. In both studies, only 18 of 106,51 and 5 of 66 patients,52 respectively, underwent subsequent liver biopsies and progression of NAFLD to cirrhosis was noted in 1 patient in each study. It was also noted that children with NAFLD had 13.6 times higher mortality risk compared to the expected survival of the general American population of the same age and sex.52

A meta-analysis of adult studies with paired liver biopsies determined an average fibrosis progression rate by one stage over 7 years for NASH patients and 14 years per stage for those with simple steatosis (SS).53 Taking into consideration that NAFLD in children is usually diagnosed at the ages of 12-13 years, 25%-50% have NASH at diagnosis, and 10%-25% might present with AF,54 it could be estimated that more than one half of these children would have cirrhosis by the age of 40 if no therapeutic measures were undertaken. In support of this, a recent analysis of all liver transplantations (LTs) performed in children and AYAs between 1987 and 201255 showed that NASH had increased as an indication for LT in this population. Although most LT recipients were aged 34-40 years, 30% were younger than 34 years, and 4% of the total cohort (14 out of 330 subjects) were children. Long-term outcome post-LT was suboptimal, with overall 30% (100 of 330) dying and 11.5% (38 of 330) requiring retransplantation over a median of 46 months. The most common causes of death after first LT were infection in 25% and graft failure in 17%. One third of the patients requiring retransplantation had recurrent NASH. Recurrence of NASH in the allograft was also reported in one of the pediatric follow-up studies.52

Diagnostic Modalities

LABORATORY TESTS AND NONINVASIVE SCORES

There is an unmet need for reliable noninvasive tests evaluating disease severity in NAFLD. Studies in adults56 and children57 have shown that plasma cytokeratin-18 (CK-18) fragments, a biomarker of hepatocyte apoptosis, could accurately differentiate NASH from SS and predict fibrosis stage. However, a more-recent large, multiethnic study showed only a modest correlation of CK-18 with NASH (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC], 0.65) and fibrosis (AUROC, 0.68).58

Several prediction scores that utilize readily available patient and laboratory data have been developed to predict the presence of AF in NAFLD, including: aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/ALT ratio; AST/platelet ratio index26; NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS); and fibrosis index with 4 components (FIB-4). However, the usefulness of these scores was questioned in a pediatric study that showed poor diagnostic accuracy for LF.59 More important, we have demonstrated that these commonly used fibrosis scores in adults with NAFLD had poor performance in young adults between the ages of 18-35 years.60 AST/ALT, AST/platelet ratio index, NFS, and FIB-4 all had either poor diagnostic accuracy or failed to diagnose the presence of any, significant, or AF. Based on our findings, we caution against the use of these scores in AYAs and urge investigators to develop new, age-specific fibrosis scores.

IMAGING MODALITIES

Abdominal ultrasound is the most commonly used imaging modality in clinical practice, given that it is a safe, widely available, and relatively inexpensive method, but it is operator dependent, has low sensitivity and specificity for HS (<20%), and cannot stage fibrosis or differentiate between SS and NASH.61 Vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE) by FibroScan (EchoSens, Paris, France) has been well studied in adults as an easy, quick, and cost-effective method that has the potential to assess both steatosis by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and fibrosis by liver stiffness measurement. However, data in AYAs are limited. A recent study compared CAP measurements with steatosis on liver biopsy in adolescents (mean age, 16) and noted that CAP can detect steatosis and discriminate between its grades.62 In addition, a study in children and adolescents has shown that VCTE accurately identifies those without fibrosis and subjects with AF (F ≥ 3), but does not differentiate well between lower stages of fibrosis.63 The main disadvantage of VCTE is the significant number of unreliable and failed measurements in obese patients despite introduction of an XL probe.64 Other imaging modalities include ultrasound-based shear wave elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

LIVER BIOPSY

Although unsuitable for screening, liver biopsy remains the reference standard for NASH diagnosis. The typical adult pattern (termed NASH type 1) is characterized by the presence of steatosis with ballooning degeneration, lobular inflammation, and/or perisinusoidal fibrosis (zone 3 lobular involvement), with the portal tracts being relatively spared.65 In children, steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis are concentrated in zone 1 of the hepatic lobule (periportal), and there is a lack of ballooning degeneration and Mallory-Denk bodies, which caused the NASH Clinical Research Network to term it zone 1 or type 2 NASH.

Complete differentiation between these two types of NASH cannot be made given that the majority of children have an overlap pattern,66 and portal chronic inflammation was shown to be associated with NASH and AF in both adult and pediatric patients.67 Moreover, it remains uncertain whether these two histological types of NASH have different natural history and prognosis. Given that AYAs represent the age of transition from childhood to adulthood, further studies are needed to determine whether NASH in this group displays specific histological features. A pilot study by our pathology department at the Cleveland Clinic has demonstrated that in a cohort of 91 young adults (aged 18-35 years) with biopsy-proven NAFLD, approximately 10% exhibited predominantly or exclusively portal-based disease, suggesting the existence of the “type 2” pattern of NAFLD in young adults, albeit less frequently than reported in children.68

Management of NAFLD in AYAs

The main challenges in the management of NAFLD in AYAs are perception of low susceptibility to diseases, low priority of health problems, and low adherence to any medical recommendations.69

Diet and regular physical activity play a key role for prevention and treatment of NAFLD. The role of these factors is even more important in AYAs given that they have preserved capacity to exercise and fewer comorbidities. A randomized study including obese adolescent males, compared the effect of aerobic and resistance training versus no exercise for 3 months.70 Reduction in HS was observed in both aerobic (P = 0.049) and resistance groups (P = 0.047) in comparison to controls. Exercise groups also demonstrated reduction of total and abdominal fat, but only resistance training was associated with significant improvement in insulin sensitivity (28%) and a small decrease in BMI. A recent, large, retrospective cohort study on participants in a Korean health screening program (mean age, 37) noted that any amount of exercise decreased the risk of development and improved existing HS, assessed by ultrasound, over a 5-year follow-up.71 Additionally, any increase in exercise dose had the same effect, independently of change in BMI. These limited data in AYAs infer that any type and dose of exercise might improve steatosis and metabolic parameters even without weight reduction, but more studies are needed to evaluate their effect on liver disease severity.

In a large, randomized trial in young adolescents that evaluated the effect of metformin and vitamin E for treatment of NAFLD (TONIC), both medications significantly improved hepatocellular ballooning, but only vitamin E therapy was associated with improvement in NAS and NASH resolution72 and could be considered as a treatment option. Both vitamin E and metformin, however, failed to achieve the primary outcome of sustained reduction in ALT level. A subset of patients that would potentially benefit from metformin includes obese young females with PCOS and NAFLD, where its use may improve insulin resistance and ameliorate androgen excess.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, an approved treatment for adults with T2DM, improve glycemic control, reduce weight, and hold promise in the treatment of NAFLD. Liraglutide, compared to placebo, showed greater resolution of NASH (39% vs. 9%; P = 0.019) and less fibrosis progression (9% vs. 36%; P = 0.04) after 1-year therapy in both diabetic and nondiabetic middle-aged obese adults (mean age, 51 years),73 but has not been studied in AYAs. Another recent, large, randomized, controlled trial has investigated the effect of farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for NAFLD, but the mean age of the study population was also 51 years.74 Future clinical trials should include more young adults or specifically focus on this age group when assessing efficacy of existing and new potential NAFLD therapies.

Transition From Pediatric to Adult Care

Transitioning from pediatric to adult care constitutes an important intersection in the management of AYAs with NAFLD. Patient education is the key for successful transition.75 A collaborative approach to educate on the role of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and unhealthy lifestyle in NAFLD development and progression is needed. Appropriate resources for teenagers should include modern technologies, such as interactive websites, online management programs, and focus groups through social networks. Future research should be centered on barriers and facilitating factors for successful transition. The applicability of Social-ecological Model of Adolescents and Young Adult Readiness to Transition (SMART), a validated multifactorial model of transition readiness,76 should be tested in AYAs with NAFLD.

Conclusion

Despite recent data showing a concerning rise of NAFLD prevalence in AYAs, current knowledge on distinct features of NAFLD in this population is insufficient. Identifying subjects at highest risk for NAFLD development and progression is of great importance given that screening measures and early prevention can have a significant impact on long-term complications of CLD. Management should include a multidisciplinary approach to address psychosocial issues, motivation, compliance, and lifestyle changes with special attention to regular exercise. Strategies to improve awareness of NAFLD and avoid risk factors among young adults should be a priority for all medical professionals and parents alike.

REFERENCES

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.