Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase in idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury†‡

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Participating centers of the Spanish group for the Study of Drug-Induced Liver Disease are listed in Acknowledgment.

Abstract

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) susceptibility has a potential genetic basis. We have evaluated possible associations between the risk of developing DILI and common genetic variants of the manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2 Val16Ala) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX1 Pro200Leu) genes, which are involved in mitochondrial oxidative stress management. Genomic DNA from 185 DILI patients assessed by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Science scale and 270 sex- and age-matched controls were analyzed. The SOD2 and GPX1 genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism and TaqMan probed quantitative polymerase chain reaction, respectively. The statistical power to detect the effect of variant alleles with the observed odds ratio (OR) was 98.2% and 99.7% for bilateral association of SOD2 and GPX1, respectively. The SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype was associated with cholestatic/mixed damage (OR = 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4-3.8; corrected P [Pc] = 0.0058), whereas the GPX1 Leu/Leu genotype was associated with cholestatic injury (OR = 5.1; 95%CI = 1.6-16.0; Pc = 0.0112). The presence of two or more combined risk alleles (SOD2 Ala and GPX1 Leu) was more frequent in DILI patients (OR = 2.1; 95%CI = 1.4-3.0; Pc = 0.0006). Patients with cholestatic/mixed injury induced by mitochondria hazardous drugs were more prone to have the SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype (OR = 3.6; 95%CI = 1.4-9.3; Pc = 0.02). This genotype was also more frequent in cholestatic/mixed DILI induced by pharmaceuticals producing quinone-like or epoxide metabolites (OR = 3.0; 95%CI = 1.7-5.5; Pc = 0.0008) and S-oxides, diazines, nitroanion radicals, or iminium ions (OR = 16.0; 95%CI = 1.8-146.1; Pc = 0.009). Conclusion: Patients homozygous for the SOD2 Ala allele and the GPX1 Leu allele are at higher risk of developing cholestatic DILI. SOD2 Ala homozygotes may be more prone to suffer DILI from drugs that are mitochondria hazardous or produce reactive intermediates. (HEPATOLOGY 2010)

The pathogenesis of unpredictable hepatic adverse reactions to drugs is so far largely unknown. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a complex and multistep process in which the interplay between the toxic potential of the drug, genetics, environmental factors, and adaptive responses determines susceptibility and occurrence of idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity.1 Because environmental factors are poorly predictive of hepatotoxicity in clinical practice,2 the rare occurrence of DILI strongly suggests that genetic polymorphisms, probably affecting several genes implicated in hepatic drug handling or intracellular detoxification, play a central role in its pathogenesis.

The mitochondria play a central role in cellular energy production and host a multitude of metabolic processes. It is also the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can lead to cellular demise. Molecular damage from ROS, a common pathway to different toxicants,3 is important in the pathogenesis of toxic liver injury. The mitochondrial enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase (E.C. 1.15.1.1, SOD2)—a critical determinant of cellular defence against toxic insult to the liver—is the major scavenger of mitochondrial superoxide. The SOD2 mutant C allele (T > C polymorphism in codon 16 of the mitochondrial targeting sequence resulting in an alanine for valine substitution) allows the preprotein to be more efficiently imported into the mitochondrial matrix and subsequently enhanced mitochondrial activity of the mature protein.4 Surprisingly, the more efficient C variant allele has been shown to increase the susceptibility to DILI, particularly related to antituberculosis drugs, but also to other drugs, in Taiwanese patients.5 This unexpected finding has been attributed to the accumulation of higher amounts of hydrogen peroxide generated by the enhanced SOD2 activity.

In addition to SOD2, glutathione peroxidases can modulate the intracellular level of hydrogen peroxide. Glutathione peroxidase 1 (E.C. 1.11.1.9, GPX1) is part of the cellular antioxidant defence system by catalyzing the reduction of hydrogen peroxide (and various organic hydroperoxides) to water using reduced glutathione as a co-substrate. GPX1 is the main glutathione peroxidase in the mammalian liver and plays a significant role in preventing mitochondrial oxidative stress.6 A polymorphism in codon 200, initially assigned to codon 198 of the human GPX1 gene and designated as rs1050450, encodes for either a proline or a leucine amino acid. The presence of a leucine at this position has been shown to reduce enzyme activity by 40%.7

Scarce information is available on polymorphisms in the SOD2 and GPX1 genes in Caucasian patients and their relevance in DILI development susceptibility. To perform a more comprehensive approach to the study of mitochondrial antioxidant genetics in DILI, this study was undertaken to investigate potential associations between the SOD2 Val16Ala and GPX1 Pro200Leu polymorphisms and the risk of developing idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity.

Abbreviations:

CI, confidence interval; CNS, central nervous system; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase-1; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OR, odds ratio; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD2, manganese superoxide dismutase.

Patients and Methods

Subjects and Study Protocol.

Cases of DILI were selected from those submitted to the Spanish DILI Registry, in use in southern Spain since 1994 and coordinated by two of the authors (R.J.A. and M.I.L.).The operational structure of the registry, data recording, and case ascertainment have been reported elsewhere.8 The report form contains full information necessary to ascertain causality: 1) the temporal relationship between start of drug intake and appearance of liver disease, and the time between discontinuation of treatment and improvement in or recovery from liver dysfunction; 2) serology and biochemical data to exclude viral hepatitis and autoimmune and metabolic liver disease, as well as appropriate imaging tests to rule out bile duct disorders; and 3) the outcome of liver damage. All submitted cases are further evaluated for causality assessment, initially by clinical assessment and later by application to the Council for International Organizations of Medical Science scale.

The pattern of liver injury is classified according to the International Consensus Meeting Criteria.9 The liver tests used for the classification of liver damage were the first blood test available after liver injury. Alternatively, liver damage was determined on the basis of liver biopsy findings when available. Cases were classified as hypersensitivity in nature if any of the following clinical laboratory findings were presented: fever, rash, serum eosinophilia, cytopenia, or pathological findings (eosinophil-rich infiltrates or granulomas) on biopsy specimens. Cases were defined as chronic if laboratory liver tests showed persistent abnormality more than 3 months after stopping drug therapy for hepatocellular pattern of damage or 6 months for cholestatic/mixed type of injury. The drugs responsible for hepatic reactions were classified according to the Anatomic Therapeutic Classification recommended by World Health Organization—Europe.10 The aforementioned drugs were also classified according to their ability to form reactive intermediates (quinones, quinone methides, quinone imines, epoxides, S-oxides, diazenes, nitroanion radicals, and iminium ions) and known mitochondrial hazards based on thorough searches of published information.11-14 Patients who gave informed consent and for whom a blood sample was available were considered eligible only if the causality assessment score was “definite” or “probable.” Excluded were cases secondary to drug overdoses (acetaminophen) and occupational exposure to toxins.

As a control group for genetic polymorphism analyses, we selected 270 unrelated Caucasian subjects, sex- and age-matched to the patients analyzed. Control subjects were selected among medical students and the staff of the University of Extremadura, Spain, by three of the authors (E.G.M., C.M., and J.A.A.). Medical examination and history was obtained from each individual to exclude preexisting disorders. To check the suitability of the healthy control population chosen, an additional group composed of 103 drug-matched controls that did not experience any adverse effect (70 individuals receiving amoxicillin clavulanate: mean duration of treatment, 10 days [range, 6-14 days], mean dose 1820 mg/day, and 33 individuals receiving different classes of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] included in this study) were also included. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the coordination center at the Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital in Málaga, Spain.

DNA Extraction and Determination of SOD2 and GPX1 Genotypes.

Venous blood was obtained from each subject, and DNA was extracted as described previously.15 Genotyping of the SOD2 Val16Ala polymorphism (rs4880) was performed as previously described by Huang and co-workers.5 In brief, a 172-bp fragment containing the C47T base exchange was amplified using primers 5′-CAG CCC AGC CTG CGT AGA CGG-3′ and 5′-GCG TTG ATG TGA GGT TCC AG-3′. Amplification was performed with 40 cycles of 92°C for 1 minute, 59°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute in a total volume of 25 μL. The amplification product was digested with BsaWI restriction enzyme and followed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Alleles were distinguished on the basis of their digestion patterns, because the C47T substitution creates a restriction site for BsaWI. The restriction analysis was verified by sequencing 20 samples for each of the CC, CT, and TT genotypes.

Genotyping for glutathione peroxidase genes was carried out by means of custom TaqMan Assay (Applied Biosciences Hispania, Alcobendas, Madrid, Spain) designed to detect the following SNPs: glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1, gene ID 2876): Arg5Pro (rs8179169); Pro200Leu (rs1050450), and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4, gene ID 2879): Ser2Asn (rs8178967). The detection was carried out by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in an Eppendorf realplex thermocycler by using fluorescent probes. The amplification conditions were as follows: After a denaturation time of 10 minutes at 96°C, 45 cycles of 92°C 15 seconds, 60°C 90 seconds were carried out, and fluorescence was measured at the end of every cycle and at endpoint. All samples were determined by triplicate, and genotypes were assigned both, by the gene identification software (RealPlex 2.0, Eppendorf) and by analysis of the reference cycle number for each fluorescence curve, calculated by the use of CalQPlex algorithm (Eppendorf). For every polymorphism tested, the amplified fragments for 20 individuals carrying no mutations, 20 heterozygotes for rs1050450, one heterozygote for rs8178967, and all homozygotes for rs1050450 were sequenced, and in all cases the genotypes fully corresponded with those detected with fluorescent probes. Because the SNP rs8179169 was not identified in the study group and rs8178967 was identified only in one individual, we will refer to the SNP Pro200Leu (rs1050450) as GPX1 polymorphism in the following text.

Statistical Analysis.

Genotypic frequencies of SOD2 and GPX1 polymorphic variants were compared between DILI patients and controls using a chi-squared test. Risk alleles were defined as SOD2 C (Ala) allele and GPX1 T (Leu) allele, which reduce cellular protection against ROS. Means were compared by Student t test for independent samples. Analysis of variance was used for comparison of groups. Where variables did not follow a normal distribution, a nonparametric analysis Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess the relative disease risk conferred by a specific genotype. Analyses were performed using the SPSS 12.0 statistical software package program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To account for the problem of significant associations arising by chance after multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests was applied by multiplying the probability value (P) by the number of genotypes compared (n = 3) to give a corrected P value (Pc). The statistical power of the study was evaluated as with a genetic model analyzing the frequency for carriers of the disease gene, with an RR value = 2 (type I error = 0.05), as recommended for pharmacogenomic studies.16 According to the sample size and the genotype frequencies, the power calculated for a bilateral association is the following: Association with the SOD2 polymorphism, 98.2%; association with the GPX1 polymorphism, 99.7%.

Results

Description of Overall 185 DILI Patients.

A total of 185 DILI patients, 96 women, 14 to 83 years old (mean, 54 years) were analyzed. The type of liver damage was classified as hepatocellular (n = 88) and cholestatic or mixed (n = 97). Hypersensitivity features were found in 25% of the patients. All cases were classified as highly probable (53%) or probable (47%) according to the Council for International Organizations of Medical Science scale. The main causative therapeutic group of drugs was anti-infectives (n = 59, 32%), followed by central nervous system (CNS) (n = 28, 15%), musculoskeletal system (n = 26, 14%), including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (n = 21, 11%), and cardiovascular (n = 22, 12%). Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was the treatment responsible for the highest number of cases (n = 37). There was a favorable clinical outcome in 180 patients, and a worst outcome (acute liver failure, death, liver transplantation) in five cases. The study included 168 (91%) self-limited DILI cases and 17 (9%) patients with a chronic outcome.

Genetic Polymorphisms of SOD2 and GPX1.

The SOD2 and GPX1 genotypes were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Table 1 shows the SOD2 and GPX1 genotype distribution in overall DILI patients, classified according to type of liver injury, and healthy control subjects. Both the SOD2 and the GPX1 variants were associated with enhanced risk of DILI with crude odds ratios of 1.7 (95% CI = 1.1-2.6; P = 0.02) and 1.5 (95% CI = 1.0-2.2; P = 0.04), respectively, in the overall DILI population. The SOD2 CC genotype, corresponding to Ala/Ala, was more frequently found in DILI patients with cholestatic/mixed type of injury (OR = 2.3 [95% CI = 1.4-3.8], Pc = 0.0058). Carriers of the GPX1 TT genotype, corresponding to Leu/Leu (a less frequent polymorphism occurring in only nine patients), was significantly more prevalent among patients with cholestatic injury (OR = 5.1 [1.6-16.0], Pc = 0.0112). Genotyping of an additional polymorphism in GPX1 (Arg005Pro, rs8179169) did not reveal any genotypical variations, as all DILI patients and controls were homozygous for the Arg allele. Similarly, genotyping of a GPX4 polymorphism (Ser002Asn, rs8178967) showed that 99.8% of the DNA samples analyzed were homozygous for the Ser allele.

| SOD2 | GPX1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Val/Val | Val/Ala | Ala/Ala | Pro/Pro | Pro/Leu | Leu/Leu | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Control (n = 270) | 85 (31) | 131 (49) | 54 (20) | 182 (67) | 81 (30) | 7 (3) |

| DILI (n = 185) | 40 (21) | 90 (49) | 55 (30) | 107 (58) | 69 (37) | 9 (5) |

| Hepatocellular (n = 88) | 21 (24) | 47 (53) | 20 (23) | 53 (60) | 33 (38) | 2 (2) |

| Cholestatic (n = 50) | 11 (22) | 21 (42) | 18 (36) | 29 (58) | 15 (30) | 6 (12) |

| Mixed (n = 47) | 8 (17) | 22 (47) | 17 (36) | 25 (53) | 21 (45) | 1 (2) |

| Cholestatic/Mixed | Cholestatic | |||||

| Pc | 0.0058 | 0.0112 | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | 2.3 (1.4-3.8) | 5.1 (1.6-16.0) | ||||

- Pc After Bonferroni's correction for 3 degrees of freedom according to the number of genotypes for each polymorphism; OR = odds ratio; CI = 95% confidence intervals.

- Armitage's test for trend: SOD2: chi-squared = 9.54; P = 0.008; GPX1: chi-squared = 5.48; P = 0.065.

The frequencies for SOD2 Val/Val, Val/Ala and Ala/Ala, and GPX1 Pro/Pro, Pro/Leu, and Leu/Leu genotypes did not differ between the drug-matched control groups (SOD2; 34.0%, 45.6%, and 20.4%, respectively, and GPX1; 67.0%, 31.1%, and 1.9%, respectively) and the larger control group matched for sex and age.

Genotype Distribution Classified by Main Pharmacological Groups, Formation of Reactive Intermediates, and Mitochondria Hazardous Drugs.

Genotype distribution of SOD2 and GPX1 in the main pharmacological drug groups related to DILI is outlined in Table 2. Subjects with an SOD2 Ala allele (Val/Ala or Ala/Ala genotype) had a higher risk of DILI than those with the SOD2 Val/Val genotype, both in overall drugs studied (n = 185; OR = 1.7 [1.1-2.6], Pc = 0.048) and in the CNS drugs category (n = 28; OR = 3.8 [1.1-13.0], P = 0.029/Pc = 0.058). When the analysis of the SOD2 polymorphism was restricted to patients with cholestatic/mixed liver injury, the SOD2 C allele frequency was higher among patients receiving NSAIDs (n = 12; OR = 2.2 [1.2-3.8], Pc = 0.017) and CNS drugs (n = 12; OR = 3.1 [1.7-5.6], Pc = 0.0003). Whereas the GPX1 T (Leu) allele was more frequently found in DILI patients induced by anti-infective drugs (n = 35; OR = 2.6 [1.3-4.9], Pc = 0.011). On the genotype level, the frequency of overall DILI patients carrying the GPX1 TC and TT genotypes was higher than that in the control subjects (n = 185; OR = 1.5 [1.0-2.2], P = 0.042/Pc = 0.084) and in the group receiving anti-infective drugs (n = 59; OR = 2.3 [1.3-4.1], Pc = 0.0098).

| SOD2 Val/Val n (%) | Val/Ala, Ala/Ala n/n(%) | GPX1 ProPro n (%) | Pro/ Leu, Leu/ Leu n/n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiinfectivesfor systemic use | ||||

| Antiinfectives (n = 59) | 14 (24) | 26/19 (76) | 28 (47) | 26/5 (53) |

| Antibacterials (n = 51) | 14 (27) | 21/16 (73) | 24 (47) | 23/4 (53) |

| Amoxicillin-davulanate (n = 37) | 11 (30) | 13/13 (70) | 19 (51) | 16/2 (49) |

| Macrolides (n = 5) | 2 (40) | 2/1 (60) | 4 (80) | 1/0 (20) |

| Quinolones (n = 3) | 0 (0) | 1/2 (100) | 1 (33) | 2/0 (67) |

| Other antibacterials1(n = 6) | 1 (17) | 5/0 (83) | 0 (0) | 4/2 (100) |

| Drugs for treatment of tuberculosis (n = 6) | 0 (0) | 3/3 (100) | 3 (50) | 3/0 (50) |

| Others2 (n = 2) | 0 (0) | 2/0 (100) | 1 (50) | 0/1 (50) |

| Musculo-skeletal system | ||||

| NSAIDs (n = 21) | ||||

| Diclofenac (n = 4) | 0 (0) | 4/0 (100) | 1 (25) | 3/0 (75) |

| Ibuprofen (n = 7) | 1 (14) | 2/4 (86) | 4 (57) | 3/0 (43) |

| Indometacin (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (100) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (100) |

| Naproxen (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (100) | 1 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| Nimesulide(n = 5) | 2 (40) | 3/0 (60) | 4 (80) | 1/0 (20) |

| Ketorolac (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 0/1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (100) |

| Rofecoxib (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 0/1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0/1 (100) |

| Dexketoprofen (n = 1) | 1 (100) | 0/0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (100) |

| Tetrabamate*(n = 4) | 0 (0) | 3/1 (100) | 3 (75) | 1/0 (25) |

| Others3 (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 0/1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| Central nervous system | ||||

| Antiepileptics (n = 6) | 0 (0) | 3/3 (100) | 5 (83) | 1/0 (17) |

| Anxiolytics (n = 7) | 0 (0) | 5/2 (100) | 4 (57) | 3/0 (43) |

| Antidepressants (n = 6) | 1 (17) | 4/1 (83) | 2 (33) | 4/0 (67) |

| Others4(n = 9) | 2 (22) | 3/4 (78) | 5 (56) | 4/0 (44) |

| Cardiovascular system | ||||

| ACE inhibitors + ARAII (n = 7) | 0 (0) | 5/2 (100) | 4 (57) | 2/1 (43) |

| Serum lipid reducing agents (n = 12) | 6 (50) | 3/3 (50) | 9 (75) | 3/0 (25) |

| Others5 (n = 3) | 1 (33) | 1/1 (67) | 2 (67) | 1/0 (33) |

| Drugs for peptic ulcers (n = 7) | 2 (29) | 4/1 (71) | 4 (57) | 3/0 (43) |

| Antineoplastic agents, immunosuppressive agents and endocrine therapy | ||||

| Asparaginase (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (100) | 1 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| Azathioprine (n = 4) | 0 (0) | 3/1 (100) | 1 (25) | 2/1 (75) |

| Leflunomide (n = 3) | 1 (33) | 0/2 (67) | 2 (67) | 1/0 (33) |

| Rutamide (n = 5) | 2 (40) | 2/1 (60) | 3 (60) | 2/0 (40) |

| Herbal plants (n = 7) | 1 (14) | 4/2 (86) | 5 (71) | 2/0 (29) |

| Others6 (n = 23) | 6 (26) | 12/5 (74) | 18 (78) | 4/1 (22) |

- Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARAII, angiotensin receptor antagonist II

- Drugs for peptic ulcer: ebrotidine, ranitidine, omeprazol

- Herbal plants: Camellia sinensis, Cassia anustifolia, Aesculus hippocastanum, kava, valerian

- 1 Amoxicillin, cefaclor, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, minocycline, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprin

- 2 ketoconazole, valaciclovir

- 3 alendronic acid

- 4 acetylsalicylic acid, chlorpromazine, ciclobenzaprina, clomethiazole, metamizole sodium, paracetamol, risperidone, zolmitriptan

- 5 atenolol, diltiazem, propafenone

- 6 anastozole, carbimazole, cinitapride, clomifene, clopidogrel, danazol, ethinylestradiol, extasis, finasteride, montelukast, repaglinide, stanozolol, sulfasalazine, thiamazole, tibolone, ticlopidine, transilat, zafirlukast

- * Tetrabamate contains the combination of two carbamates (febarbamate and difebarbamate) and Phenobarbital

To justify the use of the larger non–drug-matched control group, analyses were also undertaken using smaller drug-matched control groups. An association between the SOD2 C allele and cholestatic/mixed type of liver injury induced by NSAIDs was found when using the drug-matched control group (OR = 2.6 [1.4-4.5], Pc = 0.0028). In addition, no association was found between the SOD2 C allele and cholestatic/mixed type of liver injury induced by amoxicillin-clavulanate when compared with drug-matched controls, reflecting the results obtained with the larger sex- and age-matched control group. Moreover, the GPX1 allele frequency in NSAID-matched and amoxicillin-clavulanate–matched controls corresponded to those of the larger sex- and age-matched control group (Supporting Information Table 1).

The SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype distribution in DILI patients classified by the formation of reactive intermediates and according to the type of liver injury is outlined in Table 3. Patients with cholestatic/mixed type of DILI induced by quinones, quinone-like intermediates (quinone methides and quinone imines), or epoxides (n = 58) were found to be more prone to contain the SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype when compared with healthy controls (OR = 3.0 [1.7-5.5], Pc = 0.0008). Similarly, a positive association between the SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype and the risk of cholestatic/mixed type of DILI from drugs forming S-oxides, diazenes, nitroanion radicals, and iminium ions (n = 5) was observed (OR = 16.0 [1.8-146.1], Pc = 0.009).

| Quinones, Quinone Methides, Quinine Imines and Epoxides* | S-Oxides, Diazenes, Nitroanion Radicals and Iminium Ions† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR (95% Cl) | P/Pc* | n (%) | OR (95% Cl) | P/Pc | |

| DILI (n = 106*/18†) | 36 (34) | 2.1 (1.2 -3.4) | 0.005/0.02 | 9 (50) | 4.0 (1.5-10.6) | 0.005/0.01 |

| Cholestatic/Mixed (n = 58*/5†) | 25 (43) | 3.0 (1.7-5.5) | 0.0003/0.0008 | 4 (80) | 16.0 (1.8-146.1) | 0.003/0.009 |

| Hepatocellular (n = 48*/13†) | 11 (23) | 1.2 (0.6-2.5) | 0.72/1 | 5 (39) | 2.5 (0.8-7.9) | 0.15/0.46 |

- * Acetaminophen (idiosyncratic acute liver injury caused by paracetamol), acetylsalicylic acid, amitriptyline, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, atenolol, carbamazepine, chlorpromazine, cinitapride, ciprofloxacin, citalopram, clomiphene, clotiazepam, cyclobenzaprine, dexketoprofen, diazepam, diclofenac, diltiazem, estradiol, ethinylestradiol, flutamide, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, leflunomide, levofloxacin, minocycline, mirtazapine, moxifloxacin, naproxen, nimesulide, paroxetine, phenytoin, potassium clorazepate, propafenone, repaglinide, rifampicin + isoniazid, rifampicin + isoniazid + pyrazinamide, sulfamethoxazole, sulfasalazine, thiamazole, valproic acid, zafirlukast and zolmitriptan.

- † Ciprofloxacin, clomethiazole, clopidogrel, clotiazepam, isoniazid, moxifloxacin, nimesulide, pyrazinamide, rifampicin + isoniazid, rifampicin + isonazid + pyrazinamide and ticlopidine.

- Pc after Bonferroni's correction for 3 degrees of freedom; OR, odds ratio; 95% Cl, 95% confidence intervals.

Consistently, when examining SOD2 genotype distribution in patients with DILI induced by known mitochondria hazardous drugs13, 14 (Table 4), the Ala/Ala genotype was associated with a significant risk of developing cholestatic/mixed type of liver injury (n = 19, OR = 3.6 [1.4-9.3], Pc = 0.0242), but this correlation was abolished when hepatocellular type of injury was included (n = 42).

| Val/Val | Val/Ala | Ala/Ala | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Control (n = 270) | 85 (31) | 131 (49) | 54 (20) |

| Mitochondria hazardous drugs | |||

| DILI (n = 42) | 9 (21) | 20 (48) | 13 (31) |

| Cholestatic/Mixed (n = 19) | 3 (16) | 7 (37) | 9 (47) |

| Cholestatic/mixed | |||

| Pc | 0.0242 | ||

| OR (95% CI) | 3.6 (1.4-9.3) | ||

- Acetylsalicylic acid, clomifene, danazol, dexketoprofen, diclofenac, estradiol, ethinylestradiol, flutamide, ibuprofen, indomethacin, isoniazid, ketorolac, leflunomide, minocycline, naproxen, nimesulide, rofecoxib, simvastatin, tibolone, and valproic acid.

- Pc, After Bonferroni's correction for 3 degrees of freedom; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals.

There were no differences in the distribution of demographic characteristics, clinical findings, laboratory findings, and outcome among DILI patients classified by the presence of a mutant allele of SOD2 or GPX1 and the wild-type genotype. However, among the cholestatic/mixed cases, the mean age (61 years [range, 18-83 years]) was significantly higher in cases homozygous for the SOD2 Ala allele (P = 0.037).

Genotype Distribution Classified by Risk Alleles.

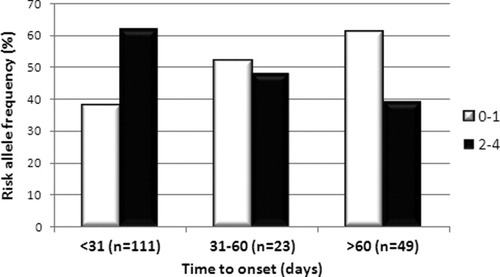

The total number of risk alleles (SOD2 C and GPX1 T alleles) was determined for each DILI patient and compared with those of the controls (Table 5). The presence of two or more risk alleles (n = 100) was significantly more frequent in DILI patients than in controls (OR = 2.1 [1.4-3.0], Pc = 0.0006), suggesting that these alleles constitute a cumulative effect on DILI susceptibility. The presence of a single risk allele (n = 52) was more frequently found in the controls (OR = 0.5 [0.4-0.8], Pc = 0.0097). Extending the risk allele analysis to also include the GSTM1 and GSTT1 null alleles determined in an earlier study17 showed a significant risk of DILI development in the presence of four or more risk alleles (OR = 3.1 [1.7-5.6], Pc = 0.0004, n = 146). To further examine the role of risk alleles in DILI development, risk allele distribution was determined in DILI patients classified by time (days) to DILI onset. When divided into three distinct “time to onset” groups (≤30 days, 31-60 days, and >60 days), a clear trend was noted whereby DILI patients with higher number of risk alleles displayed a significantly shorter time to onset (P = 0.019) (Fig. 1). Among the patients with a time to onset of 30 or fewer days, 62% contained two or more risk alleles, and 38% contained one or no risk allele. As the time to onset increased to 31 to 60 days or more than 60 days, the frequency of patients with two or more risk alleles decreased to 47% and 39%, respectively.

| Number of Risk Alleles* | DILI Patients (%) | Controls (%) | OR (95% CI) | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 33 (18) | 57 (21) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 1 |

| 1 | 52 (28) | 115 (43) | 0.5 (0.4-0.8) | 0.0097 |

| 2 | 67 (36) | 77 (28) | 1.4 (1.0-2.1) | 0.4621 |

| 3 | 31 (17) | 19 (7) | 2.7 (1.5-4.9) | 0.0074 |

| 4 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.5 (0.2-10.5) | 1 |

| ≥2 | 100 (54) | 98 (36) | 2.1 (1.4-3.0) | 0.0006 |

- * Risk alleles were defined as SOD2 C (Ala) allele and GPX1 T (Leu) allele, which reduce cellular protection against ROS.

- Pc, after Bonferroni's correction for 5 degrees of freedom; OR, odds ratio; 95% Cl, 95% confidence intervals.

Risk allele frequency classified by time to onset. Time to onset, number of days from start of medication to onset of DILI symptoms, was compared between DILI patients with low (0-1) and high (2-4) number of SOD2/GPX1 risk alleles. The frequency of low number risk allele carriers was found to increase parallel to time to onset, whereas the high number risk allele carriers was most frequent in the shortest time to onset category (<31 days) and thereafter decreased as the time to onset increased (P < 0.019).

Discussion

The role of oxidative stress in DILI development is still relatively undefined. In this study, we have looked at functional polymorphisms in SOD2 and GPX1 that both lead to enhanced H2O2 generation, to seek potential associations between enhanced ROS net levels and risk of DILI development. We found that carriers of the SOD2 Ala/Ala (CC) genotype or the GPX1 Leu/Leu (TT) genotype were both at higher risk of developing cholestatic and mixed type of DILI, but not hepatocellular type of injury. This result is not in agreement with Huang and coworkers,5 who found that the SOD2 Ala/Ala and Ala/Val genotypes increased the risk of developing hepatocellular DILI. However, most (55%) of the Taiwanese cohort were anti-tuberculosis drug–induced DILI cases, whereas only 3% of our DILI cohort corresponded to this category. Nevertheless, all of our anti-tuberculosis cases were SOD2 Ala/Ala or Ala/Val. In addition, significant ethnic differences in SOD2 genotype distribution (Supporting Information Table 2) were found between the Spanish and Taiwanese controls, which could have an impact on the expression of liver injury. Ethnic differences in allele frequencies are a major source of variability in genetic studies related to DILI.18 Findings obtained in populations with a low minor allele frequency, as is the case for SOD2 polymorphisms in Asian subjects, should be cautiously interpreted, because a high sample size is required to obtain enough statistical power in these populations.

The role of SOD2 in drug-induced hepatotoxicity has proven contradictory. Ong and coworkers19 reported that Sod2+/− knockout mice developed increased serum alanine aminotransferase activity and hepatic necrosis after prolonged troglitazone administration. However, Fujimoto and coworkers20 were unable to reproduce these results. Furthermore, although enhanced SOD2 activity and subsequently increased H2O2 levels can be beneficial for preventing cell proliferation and thus may be useful in cancer treatment,21 they can also enhance lipid peroxidation, causing mitochondrial injury.22 Careful regulation of SOD2 and ensuing H2O2 generation is thus critical to benefit from its antioxidative effects. Neither the GPX1 nor the SOD2 polymorphism is likely to manifest clinical consequences under physiological conditions but they could become apparent under conditions of additional stress, such as accumulation of hydrophobic bile acids during cholestasis or drug-mediated oxidative stress. The effect of these polymorphisms will not be compensated for by other superoxide dismutases (SOD1, SOD3) or catalase (CAT) due to the mitochondrial confinement. In addition, polymorphisms in SOD1 and catalase were not found to increase the risk of troglitazone-induced DILI.23

A wide range of drugs are known to induce DILI. The diverse characteristics of these drugs, including therapeutic effects, chemical properties, mode of administration, or biological target systems, make it difficult to establish a common denominator for DILI development. When stratifying the DILI cohort based on the responsible drug according to the anatomical therapeutic chemical classification, associations between the SOD2 C allele and enhanced risk of cholestatic/mixed type of liver injury induced by CNS-targeting drugs and the NSAID subgroup of the musculoskeletal system targeting drugs emerged. The fact that the CNS and NSAID drugs involved in this study diverge with respect to biological targets and mode of action suggests that these drugs may have a common denominator in their chemical structure. Indeed, 68% and 95% of the drugs composing our CNS and NSAID groups, respectively, are known to produce quinones, quinone-like, or epoxide intermediates during bioactivation. The electrophilic nature of these reactive intermediates make them prone to form adducts with DNA and cellular proteins as well as glutathione, that may proceed to liver injury.11 Glutathione adduct formation can be viewed as a potential detoxification pathway; however, this process also depletes glutathione stores, thus limiting its use as a reducing equivalent, which in conjunction with additional ROS sources could have damaging consequences. In addition, quinones are highly redox active compounds that can redox cycle with their corresponding semiquinones and hydroquinones to form ROS,11 thus providing an additional source of intracellular ROS.

These results prompted us to look deeper into the chemical structure of individual drugs. Many drugs undergo bioactivation in the liver that may or may not lead to the formation of reactive intermediates or metabolites, such as quinones, epoxides, and diazenes, that could potentially cause cellular damage.11, 12 Focusing on the chemical structure of reactive metabolites/intermediates formed rather than the parent drug may thus provide better insight into the underlying mechanism and equivalent determinants of DILI development. Both of the two groups of reactive intermediates focused on in this study displayed a significant association between the SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype and the risk of developing cholestatic/mixed type of liver injury. This was seen especially in the S-oxides, diazenes, nitroanion radicals, and iminium ions forming group, where the intermediates in general are more reactive than those in the quinone/epoxide group, and potentially cause nucleophilic attacks.

In clinical practice, drugs have traditionally been classified according to their therapeutic groups. This may not be the optimal classification system in terms of drug toxicity or DILI potential. Reactive drug metabolites appear to be a better classification criterion. Drugs with an aromatic amine functional group, for example, are associated with a relatively high incidence of idiosyncratic drug reactions because of their ability to form reactive metabolites, independent of the therapeutic class.24 Our data highlight the relevance of reactive intermediates generated from parent drugs in DILI and the importance of considering this issue in hepatotoxicity ascertainment and drug development.

Various drugs associated with idiosyncratic DILI are known to exhibit mitochondrial hazards.13, 14 Although these drugs do not produce a human health risk alone, underlying genetic abnormalities could sensitize the mitochondria to these drug effects and potentially lead to the development of DILI. Kashimshetty and co-workers25 recently showed that an underlying mitochondrial abnormality in the liver must be present to produce flutamide-induced hepatoxicity.25 Furthermore, DILI onset is often delayed, a characteristic compatible with cumulative damage requiring a threshold level to be reached before overt damage appears, pointing toward the mitochondria as the DILI battlefield. Our results are supportive of a pivotal role for SOD2 in mitochondria hazardous drug-induced liver injuries, with carriers of the SOD2 Ala/Ala genotype being 3.6 times more likely to develop cholestatic/mixed type of DILI. This may not come as a surprise, considering that 83% of the mitochondria hazardous drugs in our cohort also fall into the quinone/epoxide-forming category, reemphasizing the importance of the chemical structure and corresponding reactive intermediates of the drug.

Our findings suggest that the SOD2 polymorphism studied is related to cholestatic/mixed type of DILI. Subsequently, oxidative stress may have a bigger influence on cholestatic/mixed than hepatocellular type of liver injury. Indeed, retention of hydrophobic bile acids is known to enhance mitochondrial oxidative stress.26 The fact that cholestatic patients are generally older than hepatocellular patients supports a role for SOD2 in cholestatic injury, as the antioxidant defence system is known to decline with age.8, 27 In line with this theory was the finding that our cholestatic/mixed DILI cases homozygous for the SOD2 Ala allele had a higher mean age than the corresponding heterozygous DILI cases.

In an earlier study, we found that the presence of either the GSTM1 or GSTT1 null allele was associated with low or no increased risk of developing DILI, respectively, but that carriers of both null alleles had a 2.7-fold increased risk for DILI.17 This suggests that the two GST genes have a synergistic role in DILI development. Similarly, the SOD2 and GPX1 polymorphisms synergistically enhance the risk of DILI, irrespective of the type of liver injury as DILI patients were more likely to contain two or more risk alleles (SOD2 Ala and GPX1 Leu allele). Combined sources of oxidative stress are therefore more likely to lead to DILI development, probably because of cumulative mitochondrial dysfunction, and have the potential to overcome the disease threshold faster, as seen in the shorter time to onset in cases with two or more risk alleles. Diplotypes abundant in pro-oxidant alleles are consequently disadvantageous to the cell. The number of pro-oxidant alleles is therefore limited, and none of our cases or controls was found to be homozygous for the SOD2 Ala and GPX1 Leu alleles as well as GSTM1/T1 double nulls.

In conclusion, carriers of the SOD2 Ala/Ala and GPX1 Leu/Leu genotype are more susceptible to developing cholestatic/mixed type of DILI. The risk of DILI is augmented with drugs forming reactive intermediates during bioactivation. The SOD2 Ala and GPX1 Leu risk alleles have a synergistic effect on the risk of DILI, and increased number of risk alleles appear to shorten the time to disease onset.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank D. Ramón Hidalgo of the Servicio Central de Informática de la Universidad de Málaga for his invaluable help in the statistical analyses. The funding source had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

On behalf of the Spanish group for the Study of Drug-Induced Liver Disease:

Participating clinical centers: Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga (centro coordinador): C. Stephens, R. J. Andrade, M. I. Lucena, M. García-Cortés, A Fernandez-Castañer, Y. Borraz, E. Ulzurrun, M. Robles, J. Sanchez-Negrete, I. Moreno, C. Stephens, J. Ruiz.

Hospital Torrecárdenas, Almería: M. C. Fernández, G. Peláez, R. Daza, M. Casado, J. L. Vega, F. Suárez, M. González-Sánchez.

Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme, Sevilla: M. Romero, A. Madrazo, R. Corpas, E. Suárez.

Hospital de Mendaro, Guipuzkoa: A. Castiella, E. M. Zapata.

Hospital Germans Trias i Puyol, Barcelona: R. Planas, J. Costa, A. Barriocanal, S. Anzola, N. López, F. García-Góngora, A. Borras, E. Gallardo, A. Vaqué, A. Soler.

Hospital Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla: J. A. Durán, I. Carmona, A. Melcón de Dios, M. Jiménez-Sáez, J. Alanis-López, M. Villar.

Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo: R. Pérez-Álvarez, L. Rodrigo-Sáez.

Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Granada: J. Salmerón, A. Gila.

Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga: J. M. Navarro, F. J. Rodríguez.

Hospital Sant Pau, Barcelona: C. Guarner, G. Soriano, E. M. Román.

Hospital Morales Meseguer, Murcia: Hacibe Hallal.

Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid: T. Muñoz-Yagüe, J.A. Solís-Herruzo.

Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander: F. Pons.

Hospital de Donosti, San Sebastián: M. García-Bengoechea.

Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao: S. Blanco, P. Martínez-Odriozola.

Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga: M. Jiménez, R González-Grande.

Hospital del Mar, Barcelona: R. Solá.

Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia: J. Primo, J. R. Molés.

Hospital de Laredo, Cantabria: M. Carrasco.

Hospital Clínic, Barcelona: M. Bruguera.

Hospital Universitario de Canarias. La Laguna. Tenerife: M Hernandez-Guerra.

Hospital del Tajo, Aranjuez, Madrid: O Lo Iacono.

Hospital Miguel Pecette, Valencia: A. del Val.

Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid: J. Gisbert, M Chaparro.

Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid: J. L. Calleja, J. de la Revilla.