As the clinical importance of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is increasingly appreciated, research is focusing on distinguishing its subtypes and staging the extent of hepatic fibrosis. At one end of the NAFLD spectrum is simple steatosis, and at the other end are nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), NASH-related cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The distinction between NASH and simple steatosis is important because of differences in their potential for progression.1 Generally, simple steatosis is relatively benign, but NASH can progress to cirrhosis. At present, liver biopsy with strict pathologic criteria is the only method to accurately establish the diagnosis of NASH or to stage the extent of fibrosis. Despite important technological improvements (for example, automatic biopsy guns, ultrasound guidance),2 liver biopsy remains costly and is associated with potentially important complications that occur in approximately 0.5% of cases.3 Additionally, histologic lesions of NASH may not be evenly distributed throughout the liver parenchyma, leading to sampling errors. In one study, the negative predictive value of a single biopsy for the diagnosis of NASH was at best 0.74.4 Moreover, the same study revealed that for 35% of patients, one biopsy was not enough to rule out bridging fibrosis.4 Finally, an inadequate length or fragmented biopsy specimen can make the correct diagnosis even more challenging.

Abbreviations

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; OELF, Original European Liver Fibrosis panel.

Alternatives to liver biopsy include noninvasive radiologic modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Unfortunately, most of these modalities can only detect steatosis and are unable to distinguish NASH from simple steatosis or accurately detect hepatic fibrosis.5 Nevertheless, newer technologies such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging may improve the ability of radiologic modalities to diagnose these conditions.6

Another noninvasive approach is to estimate hepatic fibrosis by assessing elasticity. In recent years, a shear elasticity probe based on 1-dimensional transient elastography has been proposed for noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis.7 This technique uses both ultrasound (5 MHz) and low-frequency (50 Hz) elastic waves with a propagation velocity directly related to elasticity. This elastographic device is called FibroScan and is distributed by Echosens (Paris, France). Its main application is for patients with chronic hepatitis C.8 At present, well-controlled studies of FibroScan in patients with NAFLD are lacking. Although the observation that hepatic steatosis does not affect liver stiffness is encouraging,9 it is likely that different cutoff values will be required for patients with NASH.

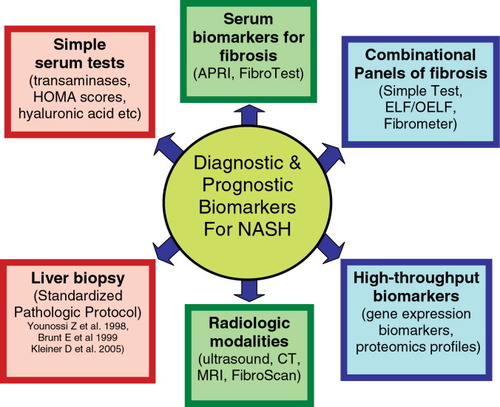

Several studies have attempted to develop clinical parameters that can reliably identify fibrosis in a cohort of patients with NAFLD (Fig. 1). Many markers have been proposed, including hyaluronic acid,10 lipid peroxidation related antibodies,11 and “predictive panels” based on the multivariate analysis of clinical and biochemical parameters.12 Several “predictive panels” have been proposed, including a relatively simple test of aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index requiring only 2 parameters.13 Another panel, the Fibrometer, is a little more complex and combines platelets, prothrombin index, AST, α2-macroglobulin, hyaluronate, urea, and age.14 The sensitivity and specificity of these tests have been evaluated only in a handful of studies. Nevertheless, the most widely used panel for fibrosis, FibroTest, has been predominantly characterized in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Although this test can reliably distinguish no fibrosis from hepatitis C virus–related cirrhosis, its ability to detect smaller changes in the stage of fibrosis have been debated.15 A recent study reported good performance of FibroTest in patients with NAFLD for detection of bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. Nevertheless, large, multicenter studies are needed to independently evaluate the value of FibroTest in patients with NAFLD.16

Various methods describing the diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for NASH. Abbreviations: APRI, AST-to-platelet ratio index; CT, computed tomography; HOMA, Homeostasis Model Assessment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging;

Two additional panels have been developed to assess hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD (Fig. 1). First, the so-called “Simple Test” for NAFLD is a relatively easy-to-use panel that includes age, hyperglycemia, body mass index, platelet count, albumin, and AST/alanine aminotransferase (ALT).17 If the purpose of performing a liver biopsy in NAFLD is to determine the extent of hepatic fibrosis, using the Simple Test can correctly stage 90% of patients, obviating the need for liver biopsy in approximately 75% of patients. In addition to this Simple Test, another panel for hepatic fibrosis is the Original European Liver Fibrosis (OELF) panel.18 OELF parameters include age, hyaluronic acid, amino-terminal propeptide of type III collagen, and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1. A simplified version of OELF is ELF, which does not include age, seems to perform well in patients with NAFLD.19 The OELF panel has been designed to stage hepatic fibrosis in several liver diseases, including NAFLD.

Despite their attractive, noninvasive utility, an important limitation of these serum-based biomarker panels is that they may reflect fibrotic pathogenetic processes occurring in other organs. To overcome this limitation, several groups20 have employed high-throughput genomic and proteomic techniques to investigate thousands of genes or proteins at one time, providing a snapshot of the pathophyiological state of the diseased tissue. The value of this approach was recently demonstrated by a comparison of the surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization (SELDI)-based proteomics index to the serum-based FibroTest, which revealed superior predictive power of the former.21 Nevertheless, the high cost and variability of the SELDI-based proteomics approach remains a substantial obstacle to the introduction of high-throughput diagnostics to clinical practice.

In this issue of HEPATOLOGY, Guha and colleagues compared the performance of ELF and OELF fibrosis panels to that of the Simple Test in patients with NAFLD.19 They showed that the performances of ELF and OELF were almost identical, so the authors were able to use the simpler version without including age. If this simplified panel were used for “ruling in” severe fibrosis, only 14% of patients with NAFLD in this cohort would have required a liver biopsy. When any degree of fibrosis was the desired outcome, this number increased to 21%. In addition, Guha and colleagues studied the performance of a combination panel that comprises clinical parameters present both in the Simple Test and in ELF. The combination panel reached an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.98 for distinguishing severe fibrosis from initial stages of the fibrotic disease in the patients with NAFLD.19 In fact, if a clinical scenario requires establishing severe fibrosis, then a higher ELF threshold of 2.2858 will result in a positive predictive value of 100% for severe fibrosis. Establishing severe fibrosis is clinically important for screening patients for liver complications such as hepatocelluar carcinoma or esophageal varices. On the other hand, the presence of any hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD may suggest a potentially progressive course. Here, an ELF threshold of 1.8454 will have a perfect positive predictive value for any fibrosis. This information can be used for establishing a patient's prognosis and for targeting these patients for aggressive lifestyle and diet modification programs or enrollment in a research protocol for NAFLD.

One limitation of the study by Guha et al.19 is the lack of adequate controls for other causes of liver fibrosis, such as infection with hepatitis C virus and/or excessive alcohol consumption. In these patients, the levels of noninvasive serum markers may be skewed, which can result in the different cut-off levels for “ruling in” and “ruling out” fibrosis. This work should also be extended to include longitudinal assessment of these fibrosis markers in patients with NAFLD to monitor progression of hepatic fibrosis.

If further validated, this noninvasive biomarker panel for fibrosis in NAFLD can be very useful in clinical practice. Together, this work by Guha and colleagues and other ongoing studies indicate that in the next few years, both serum markers of fibrosis in general, and NAFLD-related fibrosis in particular, will be translated into easy-to-use diagnostic kits and will provide viable, noninvasive alternatives to liver biopsy.22-24 When the majority of patients with NAFLD avoid this costly and potentially risky procedure, the health care savings will be substantial and the quality of life for these patients may improve.