Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus among San Francisco injection drug users, 1998 to 2000†‡

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Previous studies suggest that most injection drug users (IDUs) become infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) soon after initiating drug use. The Urban Health Study (UHS) recruited serial cross-sections of IDUs in the San Francisco Bay area from 1986 to 2005. In the current study, we determined the prevalence of antibody to HCV and HBV (core) among UHS participants during 1998 to 2000. To examine whether the time from onset of injection to acquisition of viral hepatitis has increased, we also compared the findings among recent (<10 years) initiates to drug use who participated during 1998–2000 with those who participated in 1987. Of 2,296 IDUs who participated during 1998–2000, 91.1% had antibody to HCV and 80.5% to HBV. The number of years a person had injected drugs strongly predicted infection with either virus (Ptrend < 0.0001). HCV seroprevalence among recent initiates in 1998–2000, by years of injection drug use, was: ≤2, 46.8%; 3 to 5, 72.4%; 6 to 9, 71.3%. By comparison, HCV seroprevalence among 1987 participants was: ≤2 years, 75.9%; 3 to 5, 85.7%; 6 to 9, 91.1% (P < 0.0001). A consistent pattern was observed for HBV (P < 0.0001), and these findings were not explained by demographic differences between 1987 and 1998–2000 participants. During 1987, however, 58.7% of recent initiates had shared syringes within the past 30 days compared with 33.6% during 1998–2000 (P < 0.0001). Conclusion: HCV and HBV seroprevalence among newer initiates to injection drug use in the San Francisco Bay area decreased markedly between 1987 and 1998–2000. This decrease coincided with the implementation of prevention activities among this population. (HEPATOLOGY 2007.)

Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) increases the risk of end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma.1 In the United States, infection with HCV is the most common cause of liver cancer2 and the most frequent indication for liver transplantation. Although public health practices such as screening donated blood, heat treatment of blood products, and vaccination of health care workers against HBV have markedly decreased the incidence of these infections for patients and health care workers, injection drug users (IDUs) remain at high risk of acquiring HCV3-7 and HBV.4, 8, 9 Two studies conducted in the 1980s suggested that more than 75% of IDUs became infected with HCV within the first 2 years of injection drug use4, 7; however, interventions to reduce the risk of transmission of bloodborne viruses among IDUs have since been implemented.10

The Urban Health Study (UHS) recruited serial cross-sections of IDUs in the San Francisco Bay area from 1986 through 2005 to conduct epidemiological and prevention research of bloodborne infections in this population.11-13 In an earlier report from UHS, HCV antibodies were present among approximately 75% of IDUs participating in 1987 who had initiated drug injection within the previous 2 years.7 The current analysis examines HCV and HBV seroprevalence among IDUs who participated in UHS during 1998–2000, and compares seroprevalence results among participants who had injected drugs less than 10 years with those found among participants in 1987.

Abbreviations

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBc, hepatitis B core; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV-1, human T cell lymphotrophic virus 1; IDU, injection drug user; UHS, Urban Health Study.

Patients and Methods

Subjects and Data Collection.

Every month during 1998–2000, UHS investigators recruited IDUs from street settings in 1 of 6 inner-city San Francisco Bay area neighborhoods by using targeted sampling methods.10-13 All individuals 18 years of age or older who had injected illicit drugs within the past 30 days or had previously participated in UHS were eligible for enrollment. Potential subjects were not required to disclose their name to participate. New participants were screened for visible signs of recent or chronic injection (that is, recent venipuncture sites or scars). They received modest monetary compensation ($10–$20) for each study visit and were eligible for subsequent study visits irrespective of whether they continued to inject drugs.

Trained staff obtained informed consent, interviewed participants, counseled them on reducing infection risks, and referred them to appropriate medical and social services. Participants were asked about sociodemographic characteristics, including the racial/ethnic group to which they considered themselves to belong, and their injection drug history, including age at first injection. Blood samples were collected from participants by a phlebotomist. Further details about UHS are provided elsewhere.10-13 The study was approved by the Committee on Human Subjects Research at University of California, San Francisco, and an Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute.

Because subjects could participate anonymously, we assessed possible repeated enrollment by comparing participants' fixed demographic information, including sex, birth date, race/ethnicity, state of birth, and site of enrollment. Enrollees who appeared very similar demographically were evaluated by “genetic fingerprinting” (discussed later). Among 2,351 potential subjects who participated in UHS between 1998 and 2000 and who had complete data available, we excluded subsequent data from 55 subjects with a duplicative enrollment; 2,296 subjects were included in this analysis. The 1987 UHS participants have been previously described.7

Viral Serology and Other Laboratory Tests.

We used serological testing to classify each participant's HCV and HBV infection status. To define HCV infection status, we tested for HCV antibody by HCV version 3.0 ELISA (Test System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ). Participants who were positive by HCV electroimmunoassay were considered to have been infected with HCV. To determine HBV infection status, subjects were screened for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc; HBc ELISA Test System, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ). Subjects who tested positive for anti-HBc were defined as having been infected with HBV. For the subjects who were not classified as HBV infected, we tested a specimen for antibody to HBV surface antigen (HBsAb; ETI-AB-AUK plus for anti-HBs, DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN). Those who were positive for anti-HBs were defined as vaccinated. Results of testing for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HCV RNA among these subjects will be reported in a separate publication.

Plasma from each participant was also tested for antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) by Genetic Systems rLAV EIA (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA), and reactive samples were confirmed by HIV-1 Western blot. Human T cell lymphotrophic virus (HTLV) infection status was tested using the Vironostika HTLV-I/II Microelisa System (bioMerieux, Durham, NC), and reactive samples were confirmed by HTLV Western blot version 2.4 (Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore). We performed genetic fingerprinting with the AmpFLSTR Profiler Plus PCR amplification kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to type 9 tetranucleotide short tandem repeat loci and the Amelogenin locus using deoxyribonucleic acid extracted from blood cells.

Statistical Analyses.

We determined the prevalence of infection with HCV and HBV overall, and among subgroups defined by demographic, behavioral, or viral variables. To compare prevalence among subgroups, we calculated an odds ratio (OR), a 95% confidence interval (95% CI), and a 2-sided P-value. We used the chi-square test to calculate the P-value unless an expected count for a stratum was <5, in which case we used Fisher's exact test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for potential confounding factors.14 Analyses were performed using SAS program version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).15

Results

Study Population.

Among the 2,296 subjects who participated in 1998 to 2000, the median age at the time of interview was 45 years, the median age at which the subjects first injected drugs was 19 years, and the median time from the first use of injection drugs to enrollment was 24 years (Table 1). Slightly more than 70% of the participants were men. Almost half (49.5%) of the participants considered themselves African American, 37.8% white (non-Hispanic), and 7.1% Latino. With regard to retroviral infection, 11.9% were infected with HIV-1 and 29.8% with HTLV-II.

| Characteristic (No. Subjects With Missing Data) | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | 45 | 38–49 |

| Age of first drug use (58) | 19 | 16–24 |

| Years of drug injection (59) | 24 | 15–31 |

| Number | % | |

| Sex (31) | ||

| Male | 1608 | 71.0% |

| Female | 657 | 29.0% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Latino) | 869 | 37.8% |

| African American | 1136 | 49.5% |

| Latino | 164 | 7.1% |

| Others | 127 | 5.5% |

| HIV infection (3) | 273 | 11.9% |

| HTLV-II infection | 684 | 29.8% |

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Seroprevalence of HCV and HBV in 1998 to 2000.

The overall prevalence of HCV antibody was 91.1% (Table 2). HCV seroprevalence was higher with each decade of drug use, rising from 66.2% in subjects who had injected drugs for less than 10 years to 98.7% in those who had been injecting for 30 years or longer (P < 0.0001, test for linear trend). HCV seroprevalence was also strongly associated with age, increasing from 60.8% among the 18- to 29-years-olds to 96.3% for those 50 years of age or older (Table 2). HCV seroprevalence was similar in men and women, but lower among whites than among members of other ethnic groups, who were, on average, older than the whites. In a logistic regression model that included duration of drug use, age, sex, and race/ethnicity, the adjusted odds for having been infected with HCV increased by a factor of 3.27 (95% CI = 2.63–4.07; P < 0.0001) with each decade of drug use and by 1.51 with each older age group (95% CI = 1.21–1.88; P = 0.0002). In this model, women were more likely than men to have been infected with HCV (adjusted OR, 1.68; 95% CI = 1.18–2.41; P = 0.005), but white IDUs were no longer less likely to be infected with HCV than African Americans (adjusted OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.82–1.75; P = 0.35). HCV seroprevalence exceeded 95% in participants who had also been infected with HBV, HIV-1, or HTLV-II (Table 2).

| Characteristic | HCV | HBV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Prevalence (95% CI) | P-value‡ | Number† | Prevalence (95% CI) | P-value‡ | |

| Overall | 2296 | 91.1 (89.9–92.3) | 2190 | 80.5 (78.8–82.1) | ||

| Drug use | ||||||

| ≤9 years | 355 | 66.2 (61.0–71.1) | <0.0001§ | 314 | 45.2 (39.6–50.9) | <0.0001§ |

| 10–19 years | 445 | 87.6 (84.2–90.6) | 422 | 72.0 (67.5–76.2) | ||

| 20–29 years | 751 | 97.6 (96.2–98.6) | 728 | 87.8 (85.2–90.1) | ||

| ≥30 years | 686 | 98.7 (97.5–99.4) | 670 | 94.6 (92.6–96.2) | ||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 years | 212 | 60.8 (53.9–67.5) | <0.0001§ | 175 | 48.0 (40.4–55.7) | <0.0001§ |

| 30–39 years | 475 | 87.4 (84.0–90.2) | 459 | 67.1 (62.6–71.4) | ||

| 40–49 years | 1090 | 96.1 (94.8–97.2) | 1051 | 87.1 (84.9–89.0) | ||

| ≥50 years | 519 | 96.3 (94.3–97.8) | 505 | 90.5 (87.6–92.9) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1608 | 90.9 (89.3–92.2) | 0.73 | 1534 | 82.0 (80.0–83.9) | 0.004 |

| Female | 657 | 91.3 (88.9–93.4) | 627 | 76.6 (73.0–79.8) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 1136 | 93.4 (91.8–94.8) | Referent | 1101 | 84.7 (82.5–86.8) | Referent |

| White | 869 | 87.3 (85.0–89.5) | <0.0001 | 814 | 74.0 (70.8–76.9) | <0.0001 |

| Latino | 164 | 94.5 (89.8–97.5) | 0.59 | 156 | 82.7 (75.8–88.3) | 0.51 |

| Others | 127 | 92.1 (86.0–96.1) | 0.59 | 119 | 84.0 (76.2–90.1) | 0.84 |

| HBV | ||||||

| Infected | 1764 | 97.1 (96.2–97.8) | <0.0001 | |||

| Uninfected | 532 | 71.4 (67.4–75.2) | ||||

| HCV | ||||||

| Infected | 2025 | 84.6 (83.4–86.5) | <0.0001 | |||

| Uninfected | 165 | 30.3 (22.9–36.9) | ||||

| HIV | ||||||

| Infected | 273 | 96.0 (92.9–98.0) | 0.003 | 262 | 91.6 (87.6–94.7) | <0.0001 |

| Uninfected | 2020 | 90.4 (89.1–91.7) | 1925 | 79.0 (77.1–80.8) | ||

| HTLV-II | ||||||

| Infected | 684 | 99.6 (98.7–99.9) | <0.0001 | 662 | 94.9 (92.9–96.4) | <0.0001 |

| Uninfected | 1612 | 87.5 (85.8–89.1) | 1528 | 74.3 (72.1–76.5) | ||

- * Anti-HBc.

- † HBV analyses excluded 106 individuals with serological evidence of HBV vaccination.

- ‡ P value from chi-square test unless indicated otherwise.

- § P value for trend from univariate logistic regression for each category of increase of age or duration of drug use group.

Regarding HBV infection, 106 (4.6%) of the 2,296 participants had serological evidence of hepatitis B vaccination. Compared with other subjects, vaccinees were younger (median age, 40 years) and had fewer years of injection experience (median, 14 years). Among vaccinees 51.9% were white, compared with 37.8% among all study participants (P = 0.04). We found that 17.5% of those younger than 30 years old and 11.5% of those with fewer than 10 years of drug injection experience had been vaccinated.

Among the remaining 2,190 participants, overall HBV seroprevalence was 80.5% (Table 2). HBV seroprevalence rose from 45.2% among those who had injected drugs for less than 10 years to 94.6% among those who had injected drugs for 30 years or more and from 48.0% among IDUs 18 to 29 years of age to 90.5% among those 50 years or older (P < 0.0001 for both comparisons, test for linear trend). Men were more likely to have been infected (that is, positive for anti-HBc) than women, and whites were less likely to have been infected than members of other ethnic groups (Table 2), but in a logistic regression model, these differences were largely explained by differences in the duration of injection drug use. In this model, the adjusted OR of having been infected with HBV increased by 2.52-fold with each decade of drug use (95% CI = 2.17–2.91; P < 0.0001) and by a factor of 1.21 with each older age group (95% CI = 1.03–1.43; P = 0.02). Women were no more likely than men to have been infected with HBV (adjusted OR, 0.97; 95% CI = 0.75–1.25; P = 0.82), and HBV seroprevalence was not significantly different in whites compared with African Americans (adjusted OR, 0.84; 95% CI = 0.64–1.10; P = 0.19).

Comparison With HCV and HBV Seroprevalence in 1987.

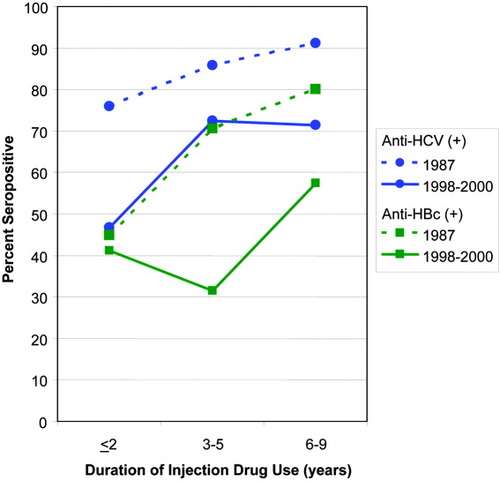

We compared HCV and HBV seroprevalence in 1998–2000 with that among UHS participants in 1987, limiting the analysis to more recent initiates who had injected drugs for fewer than 10 years to enhance comparability. HCV seroprevalence was 66.2% among the 355 such participants during 1998–2000 as compared with 85.3% among the 109 participants in 1987 (P = 0.0001). A more detailed examination showed that HCV seroprevalence in 1998 to 2000 participants was 46.8% among those who had initiated drug injection within 2 years of enrollment, 72.4% among those who had injected drugs for 3 to 5 years, and 71.3% among those who had injected for 6 to 9 years. HCV seroprevalence among participants in 1987 was higher in each subcategory (Fig. 1; <2 years, 75.9%; 3–5 years, 85.7%; 6–9 years, 91.1%; P < 0.0001, Mantel-Haenzel summary chi-square).

Comparison of the prevalence of antibodies to HCV and HBV among street-recruited injection drug users enrolled in the San Francisco Bay area in 1987 and 1998–2000, by number of years of injection drug use (P = 0.0001 for both comparisons).

With regard to HBV, only 1 (0.9%) recent initiate to drug use in 1987 had serological evidence of hepatitis B vaccination, as compared with 11.5% (41/355) of the recent initiates in 1998–2000 (P < 0.0001 Fisher's exact test). We compared HBV seroprevalence for the 2 periods among recent initiates without serological evidence of hepatitis B vaccination and found that the results were similar to those for HCV. Overall HBV seroprevalence in 1998–2000 recent initiates was 45.2% compared with 67.6% among the 1987 participants (P < 0.0001). For each subcategory (Fig. 1), HBV seroprevalence was lower in 1998–2000 (<2 years, 41.2%; 3–5 years, 31.4%; 6–9 years, 57.4%) than in 1987 (<2 years, 44.8%; 3–5 years, 70.6%; 6–9 years, 80.0%; P < 0.0001, Mantel-Haenzel summary chi-squared).

Comparing the recent initiates to drug use in the 2 periods demographically, median age was identical (31 years), and the proportion of males (1987, 62.4%; 1998–2000, 60.6%) was very similar, but there were differences in race/ethnicity. In 1987 the distribution was: White (non-Latino), 31.2%; African American, 45.0%, Latino, 16.5%; other race/ethnicity, 7.3%. In 1998 to 2000, there were more white participants (54.4%) and fewer participants who were African American (34.7%), Latino (5.9%), or of some other race/ethnicity (5.1%). We explored whether these demographic differences explained the temporal differences in HCV and HBV seroprevalence by comparing ORs obtained from unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models. For HCV, the association between lower seroprevalence and participation during 1998–2000 (unadjusted OR = 0.34) was almost unchanged in models controlling either for race/ethnicity and duration of infection (adjusted OR = 0.35) or for race/ethnicity alone (adjusted OR = 0.37). Likewise, the association between lower HBV seroprevalence and participation during 1998–2000 (unadjusted OR = 0.40) was similar in models controlling for race/ethnicity and duration of infection (adjusted OR = 0.38) or for race/ethnicity alone (adjusted OR = 0.41).

Differences also were seen in injection practices between the two periods. During 1987, 58.7% of recent initiates reported sharing syringes within the past 30 days, compared with 33.6% of recent initiates during 1998–2000 (P < 0.0001).

Discussion

The high overall seroprevalence for both HCV and HBV among IDUs in this study is consistent with findings from other US metropolitan areas.3-7, 16, 17 That the frequency of these infections appears to have decreased markedly among new initiates to injection drug use in the San Francisco Bay area is encouraging. For example, among IDUs who had initiated drug injection within the past 2 years, HCV seroprevalence was 46.8% among 1998–2000 participants compared with 75.9% among participants enrolled in 1987. Whereas studies conducted in the 1980s4, 7 found that most IDUs rapidly became infected with HCV, our study suggests that this time has lengthened, allowing a window of opportunity before infection occurs during which effective interventions may prevent infection.21-23

Our findings are consistent with results from recent studies of young IDUs recruited in San Francisco18 and elsewhere,6, 19, 20 but an advantage of the current study is that we can compare HCV and HBV seroprevalence between cross-sectional samples of IDUs that were recruited using identical methods. These findings, and similar trends in HIV incidence in UHS participants,13 coincided with the implementation of interventions designed to enable IDUs to reduce the sharing of syringes, including street-based outreach, HIV counseling and testing, and needle exchange in San Francisco.10, 12 Previous research has shown that syringe sharing declined among IDUs after the implementation of these interventions,10 and the current study confirms a reduction in syringe sharing among recent initiates to injection.

With regard to HBV, vaccination offers another opportunity to prevent the spread of this infection.24 For the period 1998–2000, serological evidence of hepatitis B vaccination was found in only 4.6% of the participants overall, but in 11.5% of those who had injected drugs for less than 10 years and 17.5% of participants younger than 30 years of age. These findings demonstrate that hepatitis B vaccination is feasible, although still seriously underutilized, in this population.

Two important limitations of our study should be considered. First, obtaining a random sample of IDUs is generally unfeasible. For that reason, our estimates of HCV and HBV seroprevalence, which were obtained through targeted sampling, may differ from those that would have obtained had population-based sampling of IDUs in the San Francisco Bay area been possible. Second, the cross-sectional design of UHS does not permit us to directly examine whether changes in injection practices over time explain the difference in HCV and HBV seroprevalence between 1987 and 1998–2000. It should also be noted that the changes we observed in HCV and HBV seroprevalence between 1987 and 1998–2000 may not be representative of the experience of IDUs that reside in other geographic areas. It is possible that these changes are specific to San Francisco or to the United States.

Both HCV and HBV remain very common among active IDUs. To reduce the incidence of new infections, it is important to reduce the number of people who initiate injection drug use and make substance abuse treatment available to people who wish to stop.25 It is also important to note, however, that viral infections can be prevented through public health interventions with IDUs who continue to inject. If the reductions in HCV and HBV prevalence among recent initiates to injection drug use in the San Francisco Bay area can be sustained, the risk of end-stage liver disease and liver cancer should decrease in this population.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank: the Urban Health Study staff for performing the field work for this study; Violet Devairakkam and Jennifer Martin for study management; Christine Gamache, Georgina Mbisa and Wendell J. Miley for performing the viral testing; Myhanh Dotrang, Computer Sciences Corporation, for her assistance with database maintenance and data analysis; and the study participants, without whom this work would not have been possible.