Improved prognosis for patients hospitalized with esophageal varices in Sweden 1969–2002†

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Liver cirrhosis may be complicated by the development of esophageal varices. The treatment of esophageal varices has changed radically during the last 30 years. Our aim was to study whether the prognosis for patients with esophageal varices had improved in Sweden between 1969 and 2002. We linked register data from the Hospital Discharge Register and from the Causes of Death Register at The National Board of Health in Sweden between 1969 and 2002 to identify and follow-up all patients with esophageal varices according to International Classification of Diseases—8, —9, and —10. There were 12,281 patients hospitalized with esophageal varices, and for all patients there was an increase in the 5-year survival in the years between 1969 and 1979 as opposed to the years between 1990 and 2002. Better survival occurred for women compared with men, for younger patients compared with older, and for patients hospitalized in the latest decade compared with the earlier decades. We found a significant decrease in the mortality caused by esophageal varices during the years studied but no decrease attributable to other causes. In conclusion, mortality for patients hospitalized with esophageal varices in Sweden decreased between 1969 and 2002. The decrease is seen for both 1- and 5-year mortality, and this suggests that the use of new treatment strategies both for acute variceal hemorrhage and secondary prophylaxis has had an impact on prognosis. (HEPATOLOGY 2006;43:500–505.).

The treatment of esophageal varices has changed radically during the last 40 years, from shunt-surgery and balloon tube tamponade for acute variceal hemorrhage to the multi-modality treatment of today with pharmacological, endoscopic, surgical, and invasive radiological therapies.1-5

Sclerosing of esophageal varices became common in Sweden in the mid-1980s, and liver transplantation has been performed in Sweden since 1984.6 Prophylactic antibiotics, somatostatin, and terlipressin have been in use since the beginning of the 1990s.

Hemorrhage from esophageal varices is a frequent cause of death among patients with cirrhosis, and the average mortality after the first variceal bleeding is reported to be 30% to 50%.7, 8 The current state-of the-art treatment for acute variceal hemorrhage includes endoscopic and pharmacological control with intravenous administration of vasoactive drugs and antibiotics. This has been reported to reduce mortality.9 Secondary prophylaxis includes pharmacological agents, such as propanolol, and follow-up programs with endoscopic eradication and surveillance of varices and interventional radiological procedures.10 Randomized controlled trials exist on well-defined patient groups treated for bleeding and prophylaxis against rebleeding.11 Long-term studies in a population-based setting have shown a reduced mortality rate.12-15

The aim of this study was to assess whether the prognosis for patients hospitalized with esophageal varices in Sweden between 1969 and 2002 had improved both in the short and long term, and to study whether changes in the survival were similar by sex and age groups. The study hypothesis was that there has been an improvement in survival rate for patients hospitalized with esophageal varices in Sweden during the study period.

Abbreviation:

ICD, International Classifications of Diseases.

Materials and Methods

All Swedish residents have a national registration number that is a unique personal identifier. The National Board of Health and Welfare has collected data on individual hospital discharges in Sweden since 1964 in the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register, and since 1987 it is complete for the whole country. The recruitment of patients was done county by county as the counties entered the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register. Each entry contains the national registration number, administrative and medical data, such as the hospital department, discharge diagnosis, duration of stay, age, sex, and county of residence. In later years, between 1.4 and 1.7 million discharges per year from public hospitals have been registered; hospitals in Sweden are predominantly state-owned. The personal identification numbers are lacking in fewer than 1% of all discharges, mostly children and foreigners, and less than 1% are lacking a discharge diagnosis. The register also includes patients who have died during their hospitalization. The Cause of Death Register, in operation since 1952, contains information regarding the primary and secondary and underlying causes of death.16

These registers were used to identify all patients with esophageal varices diagnosed according to the International Classifications of Diseases (ICD)-8, -9, and -10.17-19 All patients who were hospitalized with esophageal varices as primary and secondary diagnosis were included. To calculate the cause-specific mortality all patients with a diagnosis of esophageal varices as primary and secondary diagnosis in the Death Certificate Register were included.

We defined esophageal varices as 456.00 according to ICD-8, and 456 A (with bleeding) and 456 B (without bleeding) in ICD-9. In ICD-10, we defined esophageal varices as I 85.0 (with bleeding) and I 85.9 (without bleeding)

Statistics

The patients were divided into three groups after their year of discharge: group I, discharged between 1969 and 1979; group II, discharged between 1980 and 1989; group III, discharged between 1990 and 2002.

The mortality rates were calculated for all patients by the Kaplan-Meyer method, and comparisons were made with the use of log-rank tests.

The cause-specific mortality was defined as the patients hospitalized with esophageal varices who were diagnosed according to ICD-8, ICD-9, and ICD-10 as deceased of esophageal varices. The data from patients who died of other causes than esophageal varices are not taken into account when calculating the cause-specific mortality. Non-variceal mortality was defined as the mortality for the patients deceased from all other causes.

Proportional hazard Cox regression models were performed on discharge groups, sex, and age.20 The model was stratified in two strata, during and after the first-year after discharge. We compared men and women, patients younger than 50 years, between 50 and 69 years, and older than 70 years, and the three different discharge groups I, II, and III. Hazard ratios were expressed as the relative hazard of death for men compared with women, and for patients older than 70 years, and those between 50 and 69 years compared with those younger than 50 years. The hazard ratio was also calculated for discharge groups II and III compared with group I.

Results

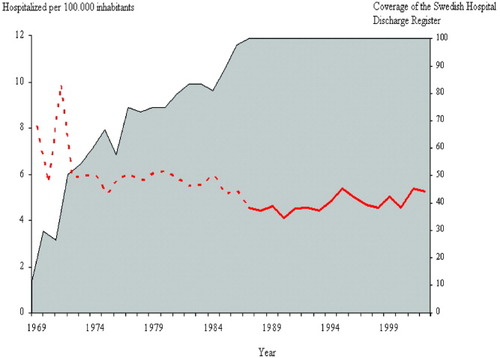

The characteristics of patients hospitalized with esophageal varices are presented in Table 1. Between 1969 and 2002,12,281 patients were hospitalized with the diagnosis of esophageal varices. The percentage of women increased from 29.3% to 33.6%. The patients' age varied from 0 to 96 years. The incidence of patients hospitalized with esophageal varices was stable at a level between 4 and 6 per 100,000 inhabitants hospitalized per year after 1972. After 1972, the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register covered more than 50% of all discharges (Fig. 1).

| Total (n) | Age (mean) | Min-max | Women (n) | % | Men (n) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 69–79 (I) | 2867 | 57.9 | 0–95 | 792 | 27.6 | 2,075 | 72.4 |

| 80–89 (II) | 3917 | 59.5 | 0–96 | 1231 | 31.4 | 2,686 | 68.6 |

| 90–02 (III) | 5497 | 60.6 | 0–96 | 1817 | 33.1 | 3,680 | 67.9 |

| Total | 12281 | 59.6 | 0–96 | 3840 | 31.3 | 8,441 | 68.7 |

- NOTE. The patients are separated into three groups by the first episode of hospitalization, between 1969 and 1979, between 1980 and 1989, and between 1990 and 2002. The total number of patients and the mean age, the age distribution, and the number and percentage of women and men are presented.

The incidence of patients hospitalized with esophageal varices between 1969 and 2002, and the coverage of the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register (gray area under the curve). The cause of the increase in number of patients hospitalized with esophageal varices seen in 1971 is unclear. After 1971, the number of patients hospitalized per 100,000 inhabitants is stable or slightly decreased. Before 1987 (dotted line), the coverage of the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register is incomplete; after 1987, the coverage is complete (full line).

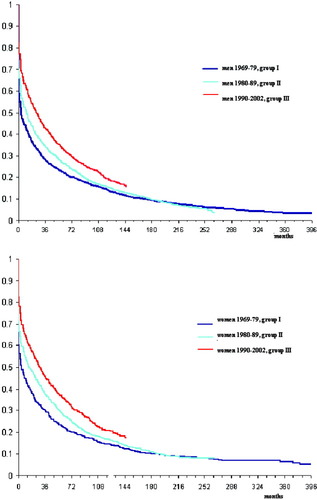

Figure 2 shows the overall mortality for men and women hospitalized with esophageal varices. The patients are divided according to the discharge periods. The first year after discharge had a high mortality rate. Statistically significant improvement in survival occurred over time (log-rank test P < .0001).

Total mortality for patients hospitalized for esophageal varices between 1969 and 2002: The patients are separated into three discharge groups. The mortality is calculated by the Kaplan-Meyer method. Men and women are presented separately. There was a statistically significant improvement in survival over time with a log-rank test P < .0001.

The 5-year survival is presented in Table 2. The patients were divided by discharge group and sex. There was an increase in survival in the discharge group III compared with I and II, between groups I and II, and between groups II and III. Women had a better survival rate than men in all age and discharge groups.

| Sex | Age | Period | Survival Rate | Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Men | <50 | 69–79 (I) | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.34 |

| 80–89 (II) | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.44 | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.52 | ||

| Men | 50–70 | 69–79 (I) | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| 80–89 (II) | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.27 | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.37 | ||

| Men | 70+ | 69–79 (I) | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| 80–89 (II) | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.16 | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.17 | ||

| Women | <50 | 69–79 (I) | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.47 |

| 80–89 (II) | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.53 | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.62 | ||

| Women | 50–70 | 69–79 (I) | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.27 |

| 80–89 (II) | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.36 | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.44 | ||

| Women | 70+ | 69–79 (I) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| 80–89 (II) | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.15 | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.23 | ||

- NOTE. The patients are separated into three discharge groups, by their sex and age, under the age of 50 years, between 50 and 70 years, and older than 70 years. Their survival rate and the confidence interval for all groups are presented.

In Table 3A, we calculated the multivariate hazard ratio of death during and after the first year after discharge for men compared with women. Improved survival was found for women compared with men; the difference was small, although significant. Table 3B shows the hazard ratio for the different age groups. As could be expected, the hazard ratio was higher among the older patients. Table 3C shows the hazard ratio for patients during the three discharge periods, I, II, and III. The hazard ratio was higher in the earlier discharge groups.

| Number of Patients | First Year After Hospitalization | After the First Year After Hospitalization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Follow-up | Deceased (n) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Time in Follow-up | Deceased (n) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

| Men | 8,441 | 4,931 | 4,036 | 1.13 (1.07–1.20) | 22,948 | 2,861 | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | ||

| Women | 3,840 | 2,343 | 1,720 | Ref. =1 | <.0001 | 11,115 | 1,306 | Ref. =1 | .0008 |

| Number of Patients | First Year After Hospitalization | After the First Year After Hospitalization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Follow-up | Deceased (n) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Time in Follow-up | Deceased (n) | Hazard Ratio (95 % CI) | P | ||

| <50 | 2,877 | 2,008 | 1,010 | Ref. = 1 | <.0001 | 13,684 | 993 | Ref. = 1 | <.0001 |

| 50–69 | 6,092 | 3,640 | 2,822 | 1.43 (1.33 – 1.53) | 16,262 | 2,127 | 1.69 (1.57 – 1.83) | ||

| 70+ | 3,312 | 1,626 | 1,924 | 2.10 (1.94 – 2.26) | 4,117 | 1,047 | 3.07 (2.81 – 3.36) | ||

| Number of Patients | First Year After Hospitalization | After the First Year After Hospitalization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Follow-up | Deceased (n) | Hazard Ratio (95 % CI) | P | Time in Follow-up | Deceased (n) | Hazard Ratio (95 % CI) | P | ||

| 69–79 (I) | 2,867 | 1,385 | 1,673 | 1.87 (1.76 – 2,00) | <.0001 | 10,181 | 1,054 | 1.05 (0.97 – 1.14) | .04 |

| 80–89 (II) | 3,917 | 2,270 | 1,954 | 1.42 (1.33 – 1.51) | 13,155 | 1,647 | 1.10 (1.02 – 1.18) | ||

| 90–02 (III) | 5,497 | 3,619 | 2,129 | Ref. = 1 | 10,726 | 1,466 | Ref. = 1 | ||

-

NOTE. Table shows the risk of death in the first year after discharge, and after the first year for patients hospitalized for esophageal varices in Sweden between 1969 and 2002:

- a

Men compared with women.

- b

The patients' age at start of follow-up, which is at discharge, older than 70 years and between 50 and 69 years compared with patients younger than 50 years.

- c

The discharge periods between 1969 and 1979 and between 1980 and 1989, compared with the period between 1990 and 2002.

- a

- The number of patients treated, the time in follow-up (years), number of deceased and the multivariate hazard ratio with the 95% confidence interval are presented. The difference between the groups is expressed as a P value.

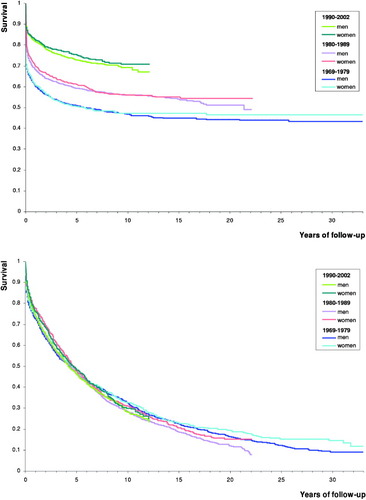

Figure 3A shows the cause-specific mortality in esophageal varices for all patients who had been hospitalized with esophageal varices between 1969 and 2002. Figure 3B shows the non-variceal mortality. In Fig. 3A and B, the patients were divided into different groups by sex and discharge group. The highest cause-specific mortality was seen in group I. Group III, which represented patients having been discharged between 1990 and 2002, had the lowest mortality. The differences in cause-specific mortality between the three discharge groups were significant, with a log rank test of P < .0001 between the three groups. No large differences were found between men and women. As can been seen in Fig. 3B, we did not find any differences in non-variceal mortality between men and women, or between the discharge groups.

(A) The cause-specific mortality for patients hospitalized for esophageal varices between 1969 and 2002: The patients are separated into three discharge groups, and by their sex. The mortality in esophageal varices as primary or secondary cause of death is calculated by the Kaplan-Meyer method. (B) The non-variceal mortality for patients hospitalized for esophageal varices between 1969 and 2002 separated into three discharge groups. Men and women are shown separately.

Table 4 shows the primary and secondary causes of death for all 9,923 patients who died after being hospitalized with esophageal varices between 1969 and 2002. The main cause of death was liver disease.

| Causes of Death | Total | Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Esophageal varices | 205 | 2.1 | 144 | 2.1 | 61 | 2.0 |

| Liver disease, with esophageal varices | 3,047 | 30.7 | 2,137 | 31.0 | 910 | 30.1 |

| Liver disease, without esophageal varices | 2,724 | 27.5 | 1,838 | 26.7 | 886 | 29.3 |

| Alcoholism, alcohol dependence | 169 | 1.7 | 140 | 2.0 | 29 | 1.0 |

| Injury, poisoning (including suicide) | 214 | 2.2 | 164 | 2.4 | 50 | 1.7 |

| Tumors (all tumors) | 1,355 | 13.7 | 908 | 13.2 | 447 | 14.8 |

| Circulation | 1,128 | 11.4 | 800 | 11.6 | 328 | 10.8 |

| Others | 1,078 | 10.9 | 765 | 11.1 | 313 | 10.4 |

- NOTE. The diagnoses are divided into the following subgroups: Esophageal varices, liver disease with esophageal varices mentioned as one of the diagnoses, and liver disease without esophageal varices mentioned as one of the diagnoses, alcoholism or alcohol dependence, injury, all tumors, circulation, and others.

Discussion

The main finding in this study is a reduction in total mortality in the studied period for patients who were hospitalized between 1969 and 2002 with esophageal varices in Sweden, and that the major change was seen in the mortality from esophageal varices. Today, effective and well-documented treatment exists for patients with esophageal varices and their complications. We might be able to prevent the development of varices in patients with liver cirrhosis without varices, or with very small varices.21 Primary prophylaxis with beta-blockers and other pharmacological agents and endoscopic band ligation reduces mortality.22, 23 A meta-analysis24 found a positive effect on all-cause mortality and bleed-related mortality, with the use of prophylactic ligation therapy. There were no differences between beta-blockers and ligation therapy. The mortality reduction we have observed are in line with earlier studies.12-15 The prophylactic therapies may have had an effect on the decrease seen in mortality; however, we suggest that the foremost cause of the mortality reduction seen is probably the improved acute treatment and secondary prophylaxis of the hospitalized patients with varices. This is in concordance with the hypothesis that the implementation of the new therapeutic strategies that has occurred during the last 30 years have improved survival. Unfortunately, discerning which therapeutic strategy has had an effect on survival with the data contained in the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register is impossible. The improved care for these patients may have had the effects seen on survival. Because the cause-specific mortality decreases and the non-variceal mortality is unchanged, the more specific therapies toward the esophageal varices may be responsible for the improvement.

The strength of this study is that both the Death Certificate Register and the Hospital Discharge Register have almost 100% coverage. Furthermore, the study includes many patients being followed for a long period, and the follow-up is almost 100%. All persons deceased in Sweden have to be reported to the Death Certificate Register. In later years, approximately 90,000 to 95,000 deaths were registered per year, and only 500 cases per year have an uncertain cause of death. Fewer than 1.5% of patients similar to those hospitalized with esophageal varices are lost to follow-up by incomplete register data or lost because of emigration. Even Swedish residents who die abroad are registered. Thus, underreporting and loss to follow-up is a minor concern to assess both total mortality and the specific mortality in esophageal varices in Sweden.

The diagnoses on the Death Certificate Register and the Hospital Discharge Register lack somewhat in specificity, as we have shown when studying the non–alcohol- and alcohol-related liver diseases.25 However, diagnosis of esophageal varices in hospitalized patients is a much more specific diagnosis, requiring endoscopic findings. The diagnosis at death may be more uncertain, because upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis may be of other origins than varices.26 Despite this drawback, we think that the diagnosis of esophageal varices is a valid and reliable diagnosis for the patients hospitalized and deceased during the period studied. The Swedish Hospital Discharge Register is incomplete until 1987, but from 1977 it covered more than 75% of all hospital discharges. After the unexplained peak in 1971, the rate of hospitalized patients discharged with the diagnosis of esophageal varices has been stable at between 4 and 6 per 100,000 inhabitants. The increase seen in the number of patients in the discharge groups from I to III may be an effect of the increasing coverage of the Hospital Discharge Register. The increased length of the discharge period between 1990 and 2002 may also explain the increase in number of patients. We do not think that the increase in number of patients is caused by recruitment of a new group of patients with reduced mortality.

The mean age at discharge increased during the period studied, from 57.9 years between 1969 and 1979 to 60.6 years between 1990 and 2002. In addition, a marked reduction in hospital beds in Sweden occurred during the period we have studied. A reduction in all hospital beds occurred, from 106,720 beds in 1969 to 31,765 in 2000, and between 1987 and 2000 a reduction from 35,097 to 19,547 in medical and surgical hospital beds occurred.27 This probably led to hospitalized patients being older and more disabled than those hospitalized in the beginning of the study period, including those patients hospitalized with esophageal varices. The increase in age and severity of other diseases for patients hospitalized in the later part of the study could have increased the mortality rate in patients hospitalized with esophageal varices in the later part of the study. The improved survival rate we have seen over time is probably larger than we have measured for comparable patients hospitalized with esophageal varices in the earlier discharge period compared with the later discharge period.

Improved 5-year survival was seen for women compared with to men, and the difference is statistically significant, although it is not a large difference when comparing the 5-year mortality in Table 2 with the cause-specific mortality and non-variceal mortality seen in Fig. 3A and B. The reason for this difference is unclear; however, liver fibrosis has been reported to progress at a slower pace in women.28

The mortality data are calculated from the first time of hospitalization with esophageal varices for each patient. This means that the first discharge group, group I, may include patients who had been hospitalized with esophageal varices earlier. The patients who had been hospitalized before 1969 with the poorest prognosis may have died earlier, and are therefore not included in group I. Thus, only the healthiest of the patients who had been admitted earlier may be included in group I. This further supports our findings of a mortality reduction in discharge groups II and III compared with group I.

In summary, our results suggest that changes in management may have altered the prognosis for patients with esophageal varices. Continuous education of physicians who diagnose and treat patients with varices are in our opinion important to ensure an effective treatment for these patients.