Examining Reasons for Using Non-Primary Care Providers as Usual Source of Health Care: Insights From the All of Us Study

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Having a primary care usual source of care (USC) is associated with better population health outcomes. However, the percent of adults in the United States (US) with a usual primary care provider is declining. We sought to identify factors associated with establishing a USC at an urgent care clinic or emergency department as opposed to primary care.

Methods

We analyzed data from 57,152 participants in the All of Us study who reported having a USC. We used the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use framework and multivariable logistic regression to examine associations among predisposing, enabling, and need factors, according to the source of usual care.

Results

An urgent care clinic, minute clinic, or emergency department was the source of usual care for 6.3% of our sample. The odds of seeking care at this type of facility increased with younger age, lower educational attainment, and better health status. Black and Hispanic individuals, as well as those who reported experiencing discrimination in medical settings or that their provider was of a different race and ethnicity, were also less likely to have a primary care USC. Financial concerns, being anxious about seeing a provider, and the inability to take time off from work also increased the likelihood of having a non-primary care USC.

Conclusions

Improving the rates of having a primary care USC among younger and healthy adults may be achievable through policies that can improve access to convenient, affordable primary care. Efforts to improve diversity among primary care providers and reduce discrimination experienced by patients may also improve the USC rates for racial and ethnic minority groups.

Abbreviations

-

- ED

-

- emergency department

-

- UC

-

- urgent care

-

- USC

-

- usual source of care

1 Introduction

Approximately 15% of US adults aged 18–64 years lack a usual source of health care [1]. A usual source of care (USC) refers to a specific doctor's office, clinic, health center, or other facility or site where a person usually goes when they are sick or need advice about their health. Having a USC is associated with greater use of preventive services, diagnosis of and awareness about chronic health conditions, and reduced mortality [2-4]. Among the 85% of US adults aged 18–64 years who have a USC, 10% report seeking usual care at an urgent care (UC) clinic, emergency department (ED), or other site rather than a primary care clinic [1].

Among individuals with a USC of any type, patients with a primary care USC have better access to high-value preventive services, such as diabetes care and counseling and less use of acute care services [5, 6]. These individuals also have higher rates of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening and are less likely to report delaying medical care [7-9]. Despite the importance of having a primary care USC, the percentage of adults in the United States with an ongoing primary care relationship that serves as their USC is declining, falling from 84% in 2000% to 75% in 2019 [6, 10]. Some racial and ethnic minority groups and individuals without insurance are also more likely to use a non-primary care provider for their source of usual care [11].

In most studies examining the characteristics of individuals with a USC, seeking usual care at a UC clinic or ED is categorized as not having a USC. Individuals who receive usual care from a UC clinic or the ED may differ from those who do not seek usual or regular health care from any source. Many interventions to discourage nonurgent ED visits have been attempted, but the number of nonurgent ED visits continues to rise, possibly because these interventions do not adequately address the determinants of nonurgent ED visits [12]. To better design interventions to increase the use of a primary care USC, studies are needed that apply a robust theoretical framework analyzing the drivers of seeking usual care at an ED or UC clinic instead of primary care. Our analysis addressed this need using the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use and the All of Us database to better understand factors that affect an individual's decision to establish a USC with a UC or ED as opposed to primary care.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

The All of Us Research Program is funded by the National Institutes of Health and has more than 340 participating sites across the United States that collect detailed health information from a diverse population [13]. The All of Us Research Program is a longitudinal cohort study aiming to enroll a diverse group of at least one million individuals across the United States so as to accelerate biomedical research and improve human health. Participants in this program are invited to complete several surveys that include questions about health care utilization, health outcomes, social determinants of health, and self-reported barriers to care, information that is not usually available in electronic health records or claims data. In this study, we used data available from the All of Us Researcher Workbench. Research using these data is not considered human subjects research by the All of Us Institutional Review Board [14].

2.2 Theoretical Framework

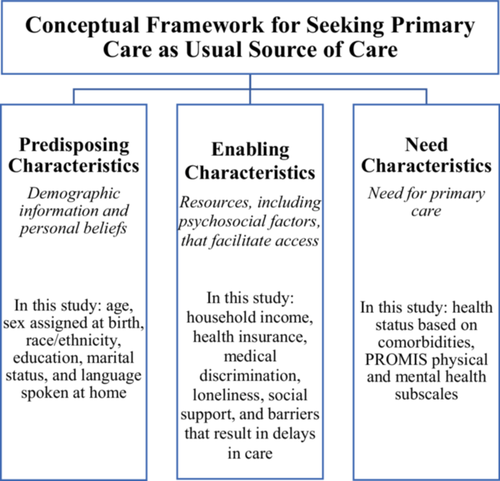

Andersen's Behavioral Model suggests that health services use is dynamic and influenced by multiple determinants such as health care system factors, population characteristics, and health behaviors [15]. Most applications of Andersen's model focus on an individual's predisposing, enabling, and need factors as key determinants of health services use [16]. One critique of studies using this model is that many fail to also consider the impact of psychosocial factors on health services utilization [17]. Recent studies have found that loneliness and a lack of social support are commonly reported psychosocial factors that affect health care utilization and are more prevalent among racial and ethnic minority groups [18-21]. Additionally, perceived provider discrimination can compromise health care access and lead to unmet health care needs in racial and ethnic minority populations [22, 23]. Given that racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to have a primary care USC, it is important to consider the effect of these psychosocial factors on the decision to establish a USC site. The measures used in this study as they apply to Andersen's model are presented in Figure 1.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Source of Usual Care

The primary outcome in this study, USC, was derived using the question, “What kind of facility do you go to most often?” for individuals who indicated that they had a USC on the Healthcare Access and Utilization Survey [24]. We created a dichotomized variable to analyze the USC. Our analysis included survey respondents who reported that their source of usual care was a doctor's office, clinic, or health center. We created a combined category of “urgent care or minute clinic or hospital emergency room” from two separate response options: “urgent care or minute clinic” and “hospital emergency room.”

2.3.2 Predisposing Factors

Predisposing factors included age, sex assigned at birth, race and ethnicity, education, marital status, and language spoken at home. These variables were obtained from The Basics Survey and the Social Determinants of Health Survey.

2.3.3 Enabling Factors

We used The Basics Survey, Healthcare Access and Utilization Survey, and Social Determinants of Health Survey to retrieve data on enabling factors such as household income and health insurance. We also included psychosocial factors measured using the Discrimination in Medical Settings Scale, UCLA Loneliness Scale, and RAND Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Scale [25-27]. For each of these scales, at least half of the questions needed to be answered for a score to be assigned; if fewer than half were answered, the data were considered missing and the participant was dropped from the sample.

The Healthcare Access and Utilization Survey inquires about 10 potential reasons why a respondent has delayed health care within the past year: lack of transportation; living in a rural area where the distance to a health provider is too far; anxious about seeing a health care provider; unable to take time off from work; unable to secure child care; deductible is too high; having to pay out of pocket; unable to afford the co-payment; providing care to an adult and unable to leave them; and provider differed from respondent in terms of race and ethnicity, religion, or native language [24]. Several of these responses were combined to create six independent categories of reasons for delaying health care. “Lack of transportation” and “living in a rural area where distance to a health provider is too far” were combined into one category representing transportation challenges. “Deductible is too high,” “having to pay out of pocket,” and “unable to afford the co-pay” were combined into one category representing financial barriers to accessing health care.

2.3.4 Need Factors

We calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) for participants, which is a measure of health status based on several different comorbidities [28]. Comorbidity information was retrieved from the Personal Health History Survey in which participants self-reported diagnoses of cancer, congestive heart failure, HIV/AIDs, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, cerebral vascular disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, liver disease, myocardial infarction, peptic ulcer disease, and peripheral vascular disease. We also applied physical health and mental health subscales derived from the PROMIS Global Health survey that were included in the Overall Health Survey [29-31]. The PROMIS physical health subscale comprises four items: physical health, physical functioning, pain, and fatigue; the PROMIS mental health subscale includes four items: mental health, emotional problems, satisfaction with discretionary social activities, and quality of life [29-31]. Aside from pain, survey responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher values representing better health. Pain was scored from 0 to 10 but was re-scored to a 5-point scale. For both PROMIS subscales, at least half of the questions had to be answered for a score to be assigned; if fewer than half were answered, the data were considered missing and the participant was excluded from the analysis.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Our sample included 81,593 individuals who participated in the All of Us study from May 31, 2017 to June 30, 2022, who provided valid demographical information, and who completed each All of Us survey from which we identified potential influencing factors. The surveys allow respondents to skip questions; we used complete case analysis, leaving a sample size of 57,152 participants. Most (96%) dropped cases were owing to missing responses for two questions: (1) reasons for delayed care among respondents indicating they had delayed care within the past year (n = 15,642) or (2) type of insurance coverage (n = 7716). Appendix A presents a demographic table comparing the original sample overall and according to USC for the final analyzed sample. Using complete case analysis, our final sample was skewed toward older participants (initial sample: 29.1% aged 18–44 years and 32.7% aged ≥ 65 years; final sample: 18.03% aged 18–44 years and 44.20% aged ≥ 65 years); however, there were no other major changes in participant demographics, overall or by USC type, for any variables included in our final model.

We examined differences in characteristics between USC groups by measuring effect sizes (reported as odds ratios [ORs] with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for each potential predisposing, enabling, and need factor [32]. We dropped two variables (i.e., health insurance and income) from the final model owing to a lack of variability (e.g., 98.2% of respondents had health insurance) and lack of specificity in the survey questions (e.g., 21% reported having multiple types of health insurance or an unknown household size for the household income question). We retained a variable assessing whether financial issues had caused respondents to delay care; this variable was deemed a more reliable indicator of financial and health insurance factors related to the ability to access care.

The remaining variables were examined using multivariable logistic regression to measure the associations between predisposing, enabling, and need factors according to the source of usual care. The generalized variance inflation factor was calculated to test for potential multicollinearity. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the overall model. Multivariable logistic regression using only selected variables, and multivariable logistic regression with probit link using all variables, were used as part of sensitivity analyses to examine robustness of the original model results. All analyses were conducted using the All of Us Research Workbench in R version 4.3.1 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3 Results

Among the 57,152 individuals in our study sample, 6.3% (n = 3592) reported their source of usual care to be a UC, minute clinic, or ED (UC/MC/ED) (Table 1). In the total sample, 81.6% of participants were non-Hispanic White, 65.6% were female individuals, and 64.5% were married or living with a partner; 91.6% had some college-level education at minimum, and 11.8% spoke another language at home. Nearly all participants (98.2%) reported having some type of health insurance, and 41.7% reported a household income of at least USD 100,000. The two most commonly reported reasons for delaying health care were financial issues (17.5%) and anxiety about seeing a provider (12.9%). The mean CCI for the entire sample was 1.16.

| Overall(N = 57,152) | Doctor's office, clinic, or health center(n = 53,560; 93.7%) | Urgent care, minute clinic, or emergency room (n = 3592; 6.3%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N (%)/M (SD) | n (%)/M (SD) | n (%)/M (SD) |

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–44 | 16,609 (29.1%) | 14,704 (27.5%) | 1905 (53%) |

| 45–64 | 21,881 (38.3%) | 20,731 (38.7%) | 1150 (32.0%) |

| 65+ | 18,662 (32.7%) | 18,125 (33.8%) | 537 (14.9%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 19,719 (34.5%) | 18,578 (34.7%) | 1141 (31.8%) |

| Female | 37,433 (65.5%) | 34,982 (65.3%) | 2451 (68.2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 46,610 (81.6%) | 43,939 (82.0%) | 2671 (74.4%) |

| Black or African American or African | 3564 (6.2%) | 3236 (6.0%) | 328 (9.1%) |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 4176 (7.3%) | 3772 (7.0%) | 404 (11.2%) |

| Other | 2802 (4.9%) | 2613 (4.9%) | 189 (5.3%) |

| Education | |||

| College Graduate | 17,861 (31.3%) | 16,762 (31.3%) | 1099 (30.6%) |

| No College | 4934 (8.6%) | 4441 (8.3%) | 493 (13.7%) |

| Some College | 13,221 (23.1%) | 12,294 (23.0%) | 927 (25.8%) |

| Advanced Degree | 21,136 (37.0%) | 20,063 (37.5%) | 1073 (29.9%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married or Living with Partner | 36,883 (64.5%) | 34,808 (65.0%) | 2075 (57.8%) |

| Divorced, Widowed, Separated, Not Married | 20,269 (35.5%) | 18,752 (35.0%) | 1517 (42.2%) |

| Speaks Other Language at Home – Yes | 6728 (11.8%) | 6183 (11.5%) | 545 (15.2%) |

| Enabling factors | |||

| Health Insurance | |||

| Purchased, Employer, or Union | 29,819 (52.2%) | 27,653 (51.6%) | 2166 (60.3%) |

| Medicare | 8166 (14.3%) | 7938 (14.8%) | 228 (6.3%) |

| Medicaid | 3964 (6.9%) | 3498 (6.5%) | 466 (13.0%) |

| Mixed/Multiple | 11,982 (21.0%) | 11,544 (21.6%) | 438 (12.2%) |

| Other (include Military or VA) | 2197 (3.8%) | 2048 (3.8%) | 149 (4.1%) |

| No Insurance | 1024 (1.8%) | 879 (1.6%) | 145 (4.0%) |

| Household income | |||

| < $50,000 | 15,929 (27.9%) | 14,613 (27.3%) | 1316 (36.6%) |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 17,384 (30.4%) | 16,392 (30.6%) | 992 (27.6%) |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 11,110 (19.4%) | 10,516 (19.6%) | 594 (16.5%) |

| $150,000 and above | 12,729 (22.3%) | 12,039 (22.5%) | 690 (19.2%) |

| Delayed Care Due Toa | |||

| Financial issues (copay, deductible, out of pocket) – Yes | 10,063 (17.6%) | 9130 (17.0%) | 933 (26.0%) |

| Transportation issues or living in rural area with large distance to provider – Yes | 4075 (7.1%) | 3666 (6.8%) | 409 (11.4%) |

| Childcare or elderly care issues – Yes | 1358 (2.4%) | 1184 (2.2%) | 174 (4.8%) |

| You were nervous about seeing a health care provider – Yes | 7356 (12.9%) | 6527 (12.2%) | 829 (23.1%) |

| Couldn't get time off work – Yes | 5323 (9.3%) | 4710 (8.8%) | 613 (17.1%) |

| Provider was different from you – Yes | 5502 (9.6%) | 4859 (9.1%) | 643 (17.9%) |

| Discrimination in Medical Settings Scaleb | 1.55 (0.62) | 1.55 (0.61) | 1.68 (0.69) |

| UCLA Loneliness Scaleb | 1.92 (0.64) | 1.91 (0.64) | 2.03 (0.67) |

| Rand MOS Social Support Scaleb | 3.96 (1) | 3.97 (0.99) | 3.88 (1.03) |

| Need Factorsb | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.16 (1.37) | 1.18 (1.38) | 0.9 (1.2) |

| Physical Health Subscale Raw Score | 3.91 (0.7) | 3.91 (0.7) | 3.85 (0.7) |

| Mental Health Subscale Raw Score | 3.63 (0.89) | 3.64 (0.89) | 3.43 (0.94) |

- a Each reason for delaying care is independent of all others, and the category subtotal does not sum to 100%.

- b A higher score on the Discrimination in Medical Settings. UCLA Loneliness Scales, and Rand MOS Social Support indicates that the respondent reported more of the item measured (discrimination, loneliness, or social support). A higher score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index indicates more severe comorbid conditions. Higher scores on the PROMIS physical and mental health subscales indicate better health.

- Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; VA, Veteran's Administration.

Depression was the most common CCI health condition reported by 33% of the entire sample (Table 2). The second most common health condition was cancer, reported by 22.5% of the overall sample. Dementia was the least commonly reported health condition for the overall sample (0.16%) and for both USC groups. For every condition but depression, the UC/MC/ED group reported a lower disease prevalence.

| Overall (N = 57,152) | Doctor's office, clinic, or health center (n = 53,560) | Urgent care, minute clinic, or emergency room (n = 3592) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health conditions | N (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| AIDs | 497 (0.8) | 476 (0.9) | 21 (0.6) |

| Cancer | 12833 (22.5) | 12361 (23.1) | 472 (13.1) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1082 (1.9) | 1028 (1.9) | 54 (1.5) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1762 (3.9) | 1700 (3.1) | 62 (1.7) |

| COPD | 1956 (3.4) | 1845 (3.4) | 111 (3.1) |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 1895 (3.3) | 1798 (3.4) | 97 (2.7) |

| Dementia | 91 (0.16) | 88 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Depression | 18851 (33) | 17587 (32.8) | 1264 (35.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5897 (10.3) | 5635 (10.5) | 262 (7.3) |

| Liver disease | 1925 (3.4) | 1838 (3.4) | 87 (2.4) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1476 (2.6) | 1409 (2.6) | 67 (1.9) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1969 (3.4) | 1851 (3.5) | 118 (3.3) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 731 (1.3) | 704 (1.3) | 27 (0.8) |

- Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3 presents the unadjusted and adjusted ORs in multivariable logistic regression. Unadjusted ORs showed that all predisposing, enabling, and need factors were significantly related to the type of USC. Among predisposing factors in the adjusted model, older age (45–64 years OR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.46–0.54; 65+ years OR: 0.30, 95% CI: 0.27–0.34) and female sex (OR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.77–0.90) decreased the odds of using UC/MC/ED as the source of usual care. Compared with individuals who had a college degree, those with no college education (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.48–1.87) and some college education (OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.07–1.30) had higher odds of using UC/MC/ED for usual care. Being single also increased the odds of UC/MC/ED use (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.18). Compared with non-Hispanic White respondents, Black or African American or African (OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.17–151) and Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish individuals were more likely to use UC/MC/ED (OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.01–1.32) whereas individuals of other races and ethnicities were less likely to use UC/MC/ED as their source of usual care (OR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.69–0.96).

| Variables | Unadjusted OR (CI) | Adjusted OR (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–44 | Ref | Ref |

| 45–64 | 0.43*** (0.40–0.46) | 0.50*** (0.46–0.54) |

| 65+ | 0.23*** (0.21–0.25) | 0.30*** (0.27–0.34) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.14*** (1.06–1.23) | 0.83*** (0.77–0.90) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref |

| Black or African American or African | 1.67*** (1.48–1.88) | 1.33*** (1.17–1.51) |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 1.76*** (1.58–1.96) | 1.16* (1.01–1.32) |

| Other | 1.19* (1.02–1.38) | 0.82* (0.69–0.96) |

| Education | ||

| College Graduate | Ref | Ref |

| No College | 1.69** (1.51–1.89) | 1.66*** (1.48–1.87) |

| Some College | 1.15*** (1.05–1.26) | 1.18** (1.07–1.30) |

| Advanced Degree | 0.82*** (0.75–0.89) | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married or Living with Partner | Ref | Ref |

| Single (Divorced, Widowed, Separated, Not Married) | 1.36*** (1.27–1.45) | 1.09* (1.01–1.18) |

| Speaks Other Language at Home – Yes | 1.37*** (1.25–1.51) | 0.98 (0.87–1.09) |

| Enabling Factors | ||

| Delayed Care Due To | ||

| Financial issues (copay, deductible, out of pocket) - Yes | 1.71*** (1.58–1.85) | 1.17*** (1.07–1.27) |

| Transportation issues or living in rural area with large distance to provider – Yes | 1.75*** (1.57–1.95) | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) |

| Childcare or elderly care issues – Yes | 2.25*** (1.91–2.64) | 1.11 (0.93–1.31) |

| You were nervous about seeing a health care provider – Yes | 2.16*** (1.91–2.35) | 1.40*** (1.28–1.54) |

| Couldn't get time off work – Yes | 2.13*** (1.95–2.34) | 1.24*** (1.12–1.37) |

| Provider was different from you – Yes | 2.19*** (1.99–2.39) | 1.36*** (1.23–1.50) |

| Discrimination in Medical Settings Scalea | 1.35*** (1.28–1.41) | 1.07* (1.01–1.14) |

| UCLA Loneliness Scalea | 1.32*** (1.25–1.39) | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) |

| Rand MOS Social Support Scalea | 0.913*** (0.88–0.94) | 0.95* (0.91–1.00) |

| Need Factorsa | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.84*** (0.81–0.86) | 0.90*** (0.87–0.93) |

| Physical Health Subscale Raw Score | 0.89*** (0.85–0.93) | 1.10** (1.03–1.17) |

| Mental Health Subscale Raw Score | 0.78*** (0.75–0.81) | 1.02 (0.96–1.07) |

- Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

- a A higher score on the Discrimination in Medical Settings. UCLA Loneliness Scales, and Rand MOS Social Support indicates the respondent reported more of the item measured (discrimination, loneliness, or social support). A higher score on the CCI indicates more severe comorbid conditions. Higher scores on the PROMIS physical and mental health subscales indicates better health.

Most enabling factors remained significant in the adjusted model. Individuals who reported delaying care owing to financial issues (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.07–1.27), being anxious about seeing a health care provider (OR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.28–1.54), being unable to take time off from work (OR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.12–1.37), and those who reported that their provider was of a different race and ethnicity (OR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.23–1.50) had a greater likelihood of using UC/MC/ED as their USC. There was also a small positive association between provider discrimination and the source of care: with increased discrimination, the odds of using UC/MC/ED as the USC were increased (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 1.01–1.14). There was also a small negative association between social support and the source of care: with increased social support, the odds of using UC/MC/ED as the USC were decreased (OR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91–1.00).

Two need factors remained significant in the adjusted model. There was a small negative association between the CCI and source of care: with increased CCI (indicating the presence of more chronic conditions), the odds of using UC/MC/ED as the USC decreased (OR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.87–0.93). There was also a small positive association between physical health and source of care: with improved self-assessed physical health, the odds of using UC/MC/ED as the USC were increased (OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.03–1.17).

4 Discussion

Our analysis using the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use identified several predisposing, enabling, and need factors associated with seeking usual care at a non-primary care facility. Among predisposing factors, Black or Hispanic racial and ethnic identity, younger age, being single, and lower education levels were associated with seeking usual care outside of a primary care setting. Our results align with past study findings showing that Black individuals are more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to use UC/MC/ED [33] because they may experience barriers to regular access to primary care, receive lower-quality care, and may have lower levels of trust in medical providers [34]. Similarly, Hispanic individuals are more likely to have a non-primary care USC, possibly owing to reasons similar to those listed above, in addition to potential language barriers that can lead to increased emergency services use and decreased primary care use [35].

We found that having a health care provider with the same cultural background enabled seeking usual care in a primary care setting. Furthermore, we found that people who experience discrimination in medical settings and those who feel anxious about seeing a health care provider were more likely to use a non-primary care USC. This could be because such individuals face challenges in communication and feel that their cultural needs are not met in other health care settings. When choosing a primary care provider, patients value factors like good communication and providers who understand their cultural background [36]. People who feel they would be treated better if they were of a different race and ethnicity or who report discrimination are more likely to delay seeking medical care or to forgo having a primary care provider [37, 38]. Additionally, fear is a significant psychological factor contributing to delayed medical care-seeking behavior among individuals who feel nervous about visiting health care providers; in our study, such fear was a factor contributing to seeking a non-primary care USC [39].

We found that younger adults were less likely to seek usual care with a primary care provider. An estimated 35%–45% of US adults under age 30 years do not have a primary care USC [40, 41]. Among all age groups, individuals with no comorbidities and those with less need for health care are less likely to have a primary care USC [41]. There are several possible reasons for this trend: healthier adults who do not require regular office visits may not see the need to establish a primary care USC and may prefer one-off appointments, when necessary, at a more accessible and convenient UC clinic or MC [42, 43]. Young adults also value the ease of online scheduling, and many report seeking care at a UC clinic owing to difficulty in scheduling an appointment with other types of providers [44]. Although young and healthy adults may not have a perceived need for primary care, this lack of an established health care relationship may lead to missed preventive care and delayed diagnoses of chronic conditions.

Nearly all individuals in our sample had health insurance, yet 17% delayed care owing to co-payments, deductibles, and cost-sharing, which was significantly higher than the estimated 6.3% of U.S. adults facing similar issues [45]. Our finding aligns with prior studies highlighting that being underinsured and having a high deductible hinder timely health care [46]. In our analysis, individuals reporting financial issues related to difficulty affording co-payments, deductibles, and out-of-pocket costs had greater odds of having a non-primary care USC. Given the cross-sectional nature of our analysis, we cannot determine whether these individuals experience financial issues owing to seeking care at more expensive UC/MC/ED sites or whether they tend to seek care at facilities such as an ED, where they cannot be turned away owing to an inability to pay. Given the large number of U.S. adults who delay care owing to cost, this issue requires ongoing policy attention. However, solutions may not be straightforward; although reducing costs can improve health outcomes, eliminating co-payments does not always increase primary care utilization. Other barriers, such as a lack of paid sick leave, must also be addressed [46-48].

We found that the inability to take time off from work increased the odds of having a non-primary care USC, which aligns with previous studies indicating that a lack of paid sick leave is a barrier to preventive care [49, 50]. Our analysis builds on reported findings that paid sick leave increases the use of cost-effective nonemergency health services and primary care [51]. Approximately 22% of the private sector workforce lacks paid sick time, with certain racial and ethnic minorities, women, workers in service occupations, part-time workers, and full-time rural workers having less access to this benefit [49, 52-54]. Mandating paid sick days at the federal level could reduce health care access disparities and improve the use of preventive services [55].

The main limitation of our study is that our sample is not representative because participants were not recruited to the All of Us study using probability sampling. Notable differences exist between our sample and the US adult population: 33% of our sample reported having depression, compared with 18.4% nationally [56]. Additionally, 81.6% of our participants were non-Hispanic White whereas the United States census reports that this proportion is 58.9% [57]. Educational attainment was higher in our sample, with 37% holding an advanced degree versus 14.4% of US adults [58]. Regarding primary care sources, only 6.3% of our respondents used a non-primary care USC, lower than the estimated 10%–25% without a primary care USC in the country [1]. There is also potential bias in the effect estimates owing to exclusion of respondents with missing data on the survey questions, particularly younger adults who were more likely to have missing data and were therefore excluded from the analysis. However, the All of Us survey includes unique predisposing, enabling, and need factors, and its representativeness may improve as more data are collected.

5 Conclusion

Transitioning individuals who seek usual care at a UC clinic or an ED to a primary care USC should improve the continuity of care and encourage greater use of preventive services, in addition to generating cost savings. For this, interventions must address multiple barriers that deter some individuals from establishing a primary care USC. Younger and healthier adults may not recognize the value of having an established primary care provider and may prefer more immediate access to care, such as that available in a UC clinic, MC, or even an ED. Increasing timely primary care through expanded evening and weekend hours may reduce unnecessary UC/MC/ED use and potential subsequent care fragmentation, as well as costs [59]. Given the ongoing primary care shortage in the United States, interprofessional care teams that include nurse practitioners and physician assistants may play an important role in expanding timely access to primary care for younger, less medically complex adults [60].

Given the well-known and wide range of health outcome disparities for Black and Hispanic populations, improving use of primary care USCs for these populations may be a step toward improved health equity. Possible mechanisms to improve use of a primary care USC in these populations may involve improving diversity among health care providers, which could also lead to improved cultural competency, better patient–provider communication, and reduced perceived discrimination among patients. Additionally, ongoing health insurance policy efforts are still needed to reduce financial barriers to seeking primary care health services.

Author Contributions

Abbey Gregg: conceptualization (lead), investigation (lead), methodology (lead), project administration (lead), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (lead). Hui Wang: data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), writing – review and editing (supporting). Brankeciara Ard: conceptualization (supporting), writing – original draft (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Marcelo Takejame Galafassi: conceptualization (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), methodology (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Maryam Bidgoli: investigation (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the All of Us study participants for their contributions, without whom this study would not have been possible. We also thank the National Institutes of Health's All of Us Research Program for making available the participant data examined in this study.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Demographic Table Comparing the Initial and Final Sample Overall and According to USC.

| Overall sample | Doctor's office, clinic, or health center | Urgent care, minute clinic, or emergency room | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Excluded | Sample | Excluded | Sample | Excluded | |||||||

| Factors | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Age: 18–44 years (ref) | 16,609 | 29.1 | 4407 | 18.03 | 14,704 | 27.5 | 3856 | 16.75 | 1905 | 53.0 | 551 | 38.83 |

| 45–64 years | 21,881 | 38.3 | 9215 | 37.70 | 20,731 | 38.7 | 8693 | 37.76 | 1150 | 32.0 | 522 | 36.79 |

| 65+ years | 18,662 | 32.7 | 10,804 | 44.20 | 18,125 | 33.8 | 10,459 | 45.43 | 537 | 14.9 | 345 | 24.31 |

| NA | 15 | 0.06 | 14 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Sex: Male (ref) | 19,719 | 34.5 | 8794 | 35.98 | 18,578 | 34.7 | 8296 | 36.04 | 1141 | 31.8 | 498 | 35.10 |

| Female | 37,433 | 65.5 | 15,647 | 64.02 | 34,982 | 65.3 | 14,726 | 63.96 | 2451 | 68.2 | 921 | 64.90 |

| Race/Ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (ref) | 46,610 | 81.6 | 20,316 | 83.12 | 43,939 | 82.0 | 19,264 | 83.68 | 2671 | 74.4 | 1052 | 74.14 |

| Black or African American or African | 3564 | 6.2 | 1610 | 6.59 | 3236 | 6.0 | 1453 | 6.31 | 328 | 9.1 | 157 | 11.06 |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 4176 | 7.3 | 1562 | 6.39 | 3772 | 7.0 | 1423 | 6.18 | 404 | 11.2 | 139 | 9.80 |

| Other | 2802 | 4.9 | 953 | 3.90 | 2613 | 4.9 | 882 | 3.83 | 189 | 5.3 | 71 | 5.00 |

| Education: College Graduate (ref) | 17,861 | 31.3 | 7224 | 29.56 | 16,762 | 31.3 | 6770 | 29.41 | 1099 | 30.6 | 454 | 31.99 |

| No College | 4934 | 8.6 | 2327 | 9.52 | 4441 | 8.3 | 2088 | 9.07 | 493 | 13.7 | 239 | 16.84 |

| Some College | 13,221 | 23.1 | 5552 | 22.72 | 12,294 | 23.0 | 5215 | 22.65 | 927 | 25.8 | 337 | 23.75 |

| Advanced Degree | 21,136 | 37.0 | 9338 | 38.21 | 20,063 | 37.5 | 8949 | 38.87 | 1073 | 29.9 | 389 | 27.41 |

| Marital Status: Married or Living with Partner (ref) | 36,883 | 64.5 | 15,692 | 64.20 | 34,808 | 65.0 | 14,892 | 64.69 | 2075 | 57.8 | 800 | 56.38 |

| Divorced, Widowed, Separated, Not Married | 20,269 | 35.5 | 8749 | 35.80 | 18,752 | 35.0 | 8130 | 35.31 | 1517 | 42.2 | 619 | 43.62 |

| Speaks Other Language at Home: Yes (ref) | 6728 | 11.8 | 2704 | 11.06 | 6183 | 11.5 | 2501 | 10.86 | 545 | 15.2 | 203 | 14.31 |

| Health Insurance: Purchased, Employer, or Union (ref) | 29,819 | 52.2 | 5714 | 23.38 | 27,653 | 51.6 | 5321 | 23.11 | 2166 | 60.3 | 393 | 27.70 |

| Medicare | 8166 | 14.3 | 3277 | 13.41 | 7938 | 14.8 | 3160 | 13.73 | 228 | 6.3 | 117 | 8.25 |

| Medicaid | 3964 | 6.9 | 1087 | 4.45 | 3498 | 6.5 | 940 | 4.08 | 466 | 13.0 | 147 | 10.36 |

| Mixed | 11,982 | 21.0 | 4453 | 18.22 | 11,544 | 21.6 | 4282 | 18.60 | 438 | 12.2 | 171 | 12.05 |

| Other (include Military or VA) | 2197 | 3.8 | 654 | 2.68 | 2048 | 3.8 | 605 | 2.63 | 149 | 4.1 | 49 | 3.45 |

| No Insurance | 1024 | 1.8 | 331 | 1.35 | 879 | 1.6 | 270 | 1.17 | 145 | 4.0 | 61 | 4.30 |

| NA | 8925 | 36.52 | 8444 | 36.68 | 481 | 33.90 | ||||||

| Household Income: < $50,000 (ref) | 15,929 | 27.9 | 7282 | 29.79 | 14,613 | 27.3 | 6717 | 29.18 | 1316 | 36.6 | 565 | 39.82 |

| $50,000–$100,000 | 17,384 | 30.4 | 7538 | 30.84 | 16,392 | 30.6 | 7137 | 31.00 | 992 | 27.6 | 401 | 28.26 |

| $100,000–$150,000 | 11,110 | 19.4 | 4500 | 18.41 | 10,516 | 19.6 | 4272 | 18.56 | 594 | 16.5 | 228 | 16.07 |

| > $150,000 | 12,729 | 22.3 | 5121 | 20.95 | 12,039 | 22.5 | 4896 | 21.27 | 690 | 19.2 | 225 | 15.86 |

- Abbreviations: NA, not available; USC, usual source of care; VA, Veteran's Administration.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the All of Us Researcher Workbench available at https://researchallofus.org/data-tools/workbench/.