Fluid inclusions, stable isotopes (H–O–S), and age constraints on the genesis of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit in the Altay, Xinjiang, NW China

Handling Editor: L. Tang

Funding information: National Key R&D Program of China, Grant/Award Number: 2017YFC0601201; Xinjiang Altay region resources compensation fund projects (Metallogenic regularity study and resource potential evaluation in the Kelan Basin, southern margin of Altay Mountains)

Abstract

The Chinese Altay in Northwest China and adjacent regions in the Russian and Mongolian Altay form a tungsten province within the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Unlike the Russian and Mongolian Altay, almost no tungsten deposits in the Chinese Altay have been reported. The Basitielieke deposit located in the Altay orogenic belt in Xinjiang is a newly discovered polymetallic tungsten deposit hosted in the skarn in the exocontact zone of a granite pluton. Mineralization can be divided into the skarn period and supergene oxidization period, the skarn period can be further divided into a prograde skarn stage (I), a retrograde skarn stage (II), and a quartz–sulphide stage (III). Scheelite mineralization mainly occurred in stage II, and Cu–Zn–Au formed in stage III. The ore-forming fluid can be divided into a H2O–NaCl systems, including stage I (211 to 480°C and 2.24 to 14.04 wt% NaCl equiv) and stage II (178 to 336°C and 4.96 to 9.47 wt% NaCl equiv), and a H2O–CO2 (±CH4/N2)–NaCl system in stage III (130 to 434°C and 1.40 to 9.60 wt% NaCl equiv). Hydrogen, oxygen, and sulphur isotope compositions indicate that magmatic water participated in the hydrothermal mineralization system in stage I, and meteoric water increased with the process of mineralization. Sulphur was derived from deep-seated magmas. The Basitielieke deposit is a reduced skarn polymetallic tungsten deposit. The deposit formed by hydrothermal fluid from the granite interacting with strata during the Early Permian, the fluid–rock interaction and fluid mixing (magmatic water and meteoric water) was the main precipitation mechanism of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB) is one of the world's largest accretionary orogens of the Palaeozoic to the Mesozoic (Chen, Pirajno, Wu, Qi, & Xiong, 2012; Jahn, 2004; Mao et al., 2008; Safonova et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2014; Yakubchuk, Cole, Seltmann, & Shatov, 2002; Yang, Li, Zhang, & Hou, 2011). The CAOB crosses parts of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia and includes a large number of Cu, Au, and polymetallic mineralization, and has a complex structural and magmatic history (Chai et al., 2009; Goldfarb, Taylor, Collins, Goryachev, & Orlandini, 2014; Hong, Wang, Xie, Zhang, & Wang, 2003; Sengör, Natal'in, & Burtman, 1993; Wang et al., 2006; Windley et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2008; Xu, Mao, Yang, Daniel, & Zheng, 2010). The Altay orogenic belt in Xinjiang, Northwest China, is an important component of the CAOB and is one of China's major muscovite, nonferrous and rare-metal metallogenic belts, which is also significant for its iron deposits (Daukeev et al., 2004; Han et al., 2014). The Altay in Xinjiang is known to host polymetallic volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) and pegmatite rare-metal deposits (Yang, Geng, Wang, Zhang, & Guo, 2018a), but no independent tungsten or polymetallic tungsten deposit has been found. The Kelan Basin is one of four basins with a concentrated distribution of nonferrous metal and iron deposits in the South Altay in Xinjiang. Some of the famous deposits in the Kelan Basin include the Abagong apatite–rich iron deposit (Chai et al., 2014), the Talate Pb–Zn–(–Fe) deposit (Li et al., 2013, 2018a, 2018b; Zhang et al., 2015), the Qiaxia Cu deposit (Zheng et al., 2014), the Tiemurt Pb–Zn–Cu deposit (Yu & Zheng, 2019; Zhang, Zheng, & Chen, 2012), the Tuomoerte Fe–(Mn) deposit (Zhang et al., 2012), and the Sarekoubu Au deposit (Xu, Zhang, Lin, Xiao, & Bian, 2020).

In 2013–2017, the Geological and Mineral Prospecting Research Institute of Nonferrous Geological Prospecting Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region discovered the Basitielieke skarn-type W–Cu–Zn deposit (including the Keziergayin, Basitielieke, and East Basitielieke ore blocks) in the southeastern Kelan Basin for the first time, where tungsten reserves reached medium in scale (Li, 2018). Its geological characteristics, induced polarization anomaly characteristics, mineral compositions, and metallogenic period have been reported (Li, 2017; Li, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019).

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit, including a detailed field survey, an optical microscopy analysis of samples, a systematic fluid inclusion study, and analyses of S and H–O isotopes, and age. These data enable us to constrain the origin of the ore-forming materials, the evolution of the ore-forming fluids, and the processes of mineralization of the Basitielieke deposit in the Altay.

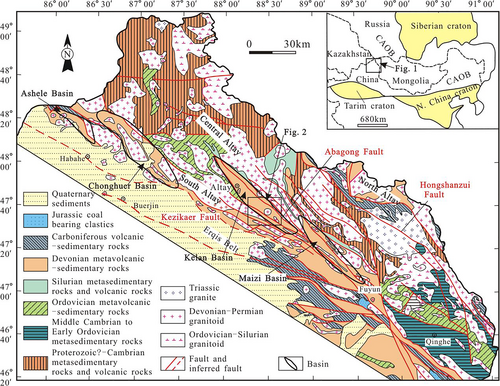

2 REGIONAL GEOLOGY

The Altay orogenic belt of Xinjiang is divided into the North, Central, and South Altay. The North Altay, located in the northern part of the Hongshanzui Fault, is mainly composed of Early Devonian to Early Carboniferous volcano-sedimentary sequences. The Central Altay, located in the central part of the Hongshanzui and the Abagong faults, is largely composed of Early Palaeozoic metamorphic rocks. The South Altay, located in the southern part of the Abagong Fault and ends at the Erqis structural belt, is composed mainly of volcano-sedimentary rocks of the Lower Devonian Kangbutiebao Formation and the Middle–Upper Devonian Altay Formation, with subordinate Carboniferous volcano-sedimentary units, as well as Middle–Upper Silurian schist, gneiss, and leptynite (Yang, Li, Yang, & Zhang, 2018b). There are four NW–SE-trending fault-bounded volcano-sedimentary basins (from northwest to southeast): the Ashele, Chonghu'er, Kelan, and Maizi basins in the South Altay (Figure 1).

The exposed strata in the Kelan Basin and along the periphery of the basin are the Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician strata (Yang, Chai, Li, Gu, & Yang, 2017), the Middle–Upper Silurian Kulumuti Group, and the Lower Devonian Kangbutiebao and Middle–Upper Devonian Altay formations (Figure 2). The Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician strata are distributed at the bottom and along the periphery of the Kelan Basin, and the main lithologies are the schist, gneiss, and metamorphic sandstone. The Kulumuti Group consists of schist and gneiss. The lower part of the Kangbutiebao Formation is composed of quartz schist, phyllite, meta-rhyolite, meta-dacite, meta-tuff, and meta-volcanic breccias. The upper part of the Kangbutiebao Formation is composed of meta-rhyolite, leptynite, meta-tuff intercalated with gneiss, chlorite biotite schist, and marble. The Altay Formation consists of shallow marine terrigenous clastic rocks intercalated with basic volcanic rocks, volcanic clastic rocks, siliceous rocks, and carbonate rocks.

The main structure in the Kelan Basin lies in a NW–SE direction, the main part of which includes the Altay complex syncline with secondary folds and faults. The Altay complex syncline axis is oriented in a NW–SE direction; the axis length is approximately 50 km, the axial plane trends towards the NE, the SW wing is normal, the NE wing is inverted, and secondary folds are widely developed. The strata in core of the syncline is the Altay Formation, and the two wings include the Kangbulibao Formation, the Kulumuti Group or the Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician strata.

The intrusions in the Kelan Basin and periphery are dominantly granites, whose ages are Middle–Late Ordovician (such as the northern Abagong–Tiemurt intrusion, 458–463 Ma, Liu et al., 2008; Chai et al., 2010), Early Devonian (such as Xiaodonggou, 401 Ma and 409 Ma, Zheng, Chai, & Yang, 2016), Permian (such as Lamazhao, 279 Ma, Wang, Hong, Tong, Han, & Shi, 2005; and Kslgui, 287 Ma, Liu, Zhang, & Yang, 2012), and Triassic (such as Shangkelan, 202 Ma, Wang et al., 2008).

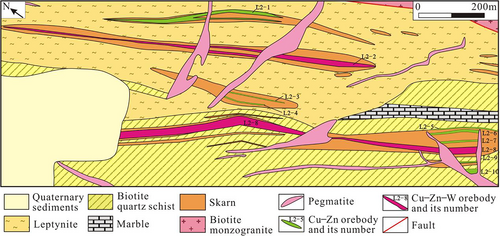

3 DEPOSIT GEOLOGY

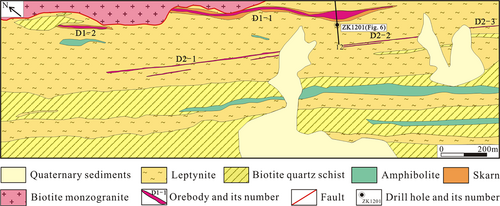

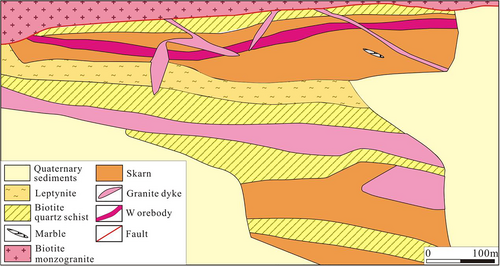

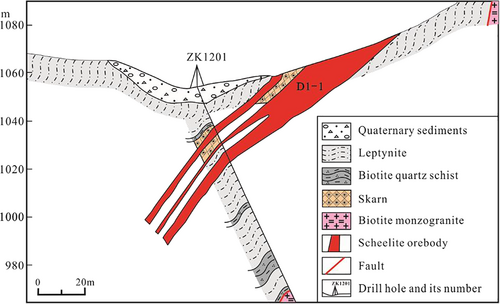

The strata exposed in the Basitielieke ore district are the Lower Devonian Kangbutiebao Formation (Figures 3, 4, and 5), which consists of amphibolite, leptynite, marble, and biotite quartz schist. Mineralization generally occurred in this formation. This ore district is located in the northeast wing of the Altay complex syncline and develops secondary folds and faults. The intrusive rock is biotite monzogranite in the northeastern ore district, which is mainly composed of K-feldspar, plagioclase, quartz, and biotite, showed fault contact with the strata and no skarn in the contact zone (Figure 6). The pegmatite dykes (with an age of 275.4 Ma from zircon LA–ICP–MS U–Pb dating, Yang et al., 2019) and granite dykes are present (Figures 4 and 5). The Abagong Fault exists throughout the northeastern ore district. Influenced by shear stress, the rock layer shows strong deformation, breakage, wrinkling, and folding.

The skarn occurs as a banded shape and is partially cut by many pegmatite dykes. The scheelite orebody mainly occurs in the skarn; the copper orebody mainly exists in the leptynite with small-scale (Li, 2018). The Basitielieke mineralized belt is approximately 16 km in length and 50–150 m in width, and includes the Keziergayin ore block (Figure 3), the Basitielieke ore block (Figure 4) and the East Basitielieke ore block (Figure 5). The Keziergayin ore block is dominated by the scheelite orebodies (D1–1, D1–2), which appears as stratiform-like and lenticular in shape, 150–850 m in length, and 4.04–30.82 m in thickness. The average grade of orebody (WO3) is 0.17%–0.28% (Li, 2018), followed by the copper orebody. The 10 polymetallic orebodies in the Basitielieke ore block are distributed in skarn as vein and lenticular in shape. L2–2 and L2–8 are the largest Cu–Zn–W orebodies, while the others are Cu–Zn or Zn orebodies. The orebody is 300–600 m in length, and 3.99–11.02 m in thickness. The average grade of orebody (WO3) is 0.061%–0.81%; the average grade of Cu is 0.25%–0.36%, the average grade of Zn is 0.67%–1.40%, and the grade of Au is 0.13–0.26 g/t. A scheelite orebody is contained within the garnet skarn as vein in the East Basitielieke ore block, which is 350 m in length and 2.71–4.85 m in thickness, and the average grade of (WO3) is 0.21%–0.59% (Geological and Mineral Prospecting Research Institute of Nonferrous Geological Prospecting Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, 2016).

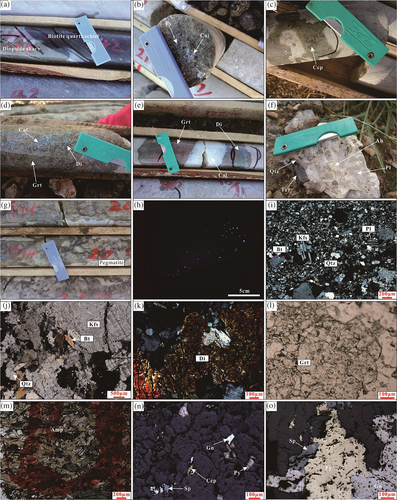

The structure of ore is mainly composed of massive, vein/veinlet, stockwork, dissemination, and agglomerate structures. The metal minerals in the ore mainly include pyrite, chalcopyrite, scheelite, sphalerite, galena, pyrrhotite, molybdenite, stannite, argentite, arsenopyrite, and natural bismuth. Nonmetallic minerals include garnet, diopside, amphibole, zoisite, epidote, quartz, biotite, fluorite, and tourmaline (Figures 7 and 8). The main component of garnet is grossular, biotite, and sphalerite rich in Fe, epidote rich in Ca, Al, and poor in Fe; the pyrrhotite, chalcopyrite, stannite, arsenopyrite, argentite, and native Bi are basically consistent with standard minerals (Zhang et al., 2019).

Wallrock alteration in the Basitielieke deposit is characterized by skarnization, followed by silicification and carbonatization, and skarn is closely related to mineralization. The skarn is developed in the Kangbutiebao Formation marble of the external contact zone with the biotite monzogranite. It is present within two to three layers (partially four to five layers) in the strata. The skarn is unevenly distributed and discontinuous. Most of the skarn occurs as thin layers consistent with bedding of strata. We can find partial marble remains in the skarn, indicating that the skarn is a product of metasomatism between magmatic hydrothermal fluid and marble. The zonation of the skarn is weak, and the skarn can be divided into diopside skarn, garnet diopside skarn, epidote garnet skarn, and epidote skarn.

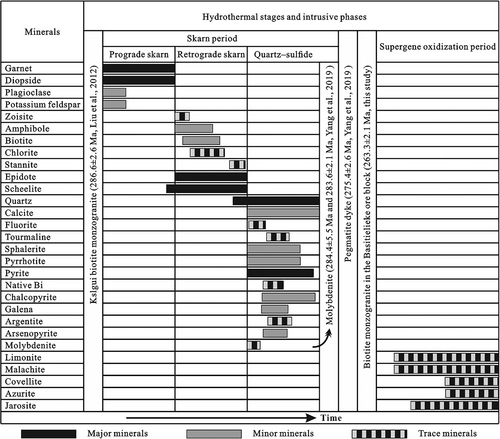

Based on the mineral assemblage, paragenetic sequence, cross-cutting relationships of ore veins, and wallrock alteration characteristics, the ore-forming process can be divided into the skarn period and supergene oxidization period, the skarn period can be further divided into three stages.

Stage I, the prograde skarn stage, is characterized by abundant garnet and diopside, and a small amount of scheelite is formed. At this stage, scheelite is mainly symbiotic with garnet and diopside, and distributed in the skarn as dotted and massive dissemination.

Stage II, the retrograde skarn stage, is marked by the formation of epidote, followed by amphibole, chlorite, quartz, biotite, zoisite, stannite, and scheelite. It is the main stage of tungsten mineralization.

Stage III, the quartz–sulphide stage, is characterized by the formation of quartz, followed by calcite, fluorite, and tourmaline. At the same time, it begins to enrich metal sulphides, such as pyrite, chalcopyrite, sphalerite, molybdenite, pyrrhotite, arsenopyrite, galena, argentite, and natural bismuth. These metallic minerals occur as dissemination, stockwork, and veinlet in the skarn. It is the main stage of Cu–Zn–Au mineralization.

4 SAMPLING AND ANALYTICAL METHODS

4.1 Samples description

Samples include garnet and diopside from stage I, epidote from stage II, and quartz from stage III were selected for fluid inclusion studies. They were taken from the Basitielieke and Keziergayin ore blocks. Double–sided polished sheet (250 to 300 μm in thickness) were prepared for petrographic observation of the mineralogy and fluid inclusions, and select representative fluid inclusions for microthermometry and component analysis.

Twenty-five samples were selected for stable isotope analyses, including three garnet and six quartz from stage I, and III for hydrogen and oxygen isotope analysis, nine sphalerite, two pyrrhotite, and five chalcopyrite from stage III for sulphur isotope measurement. All mineral separates were examined under the binocular microscope prior to isotopic analysis to ensure their purities were > 99%.

The biotite monzogranite sample was crushed before flotation and magnetic separation to remove minerals with low specific gravity. Individual zircon crystals were handpicked under a binocular microscope, then mounted in epoxy resin and polished until the grain interiors were exposed. Transmitted, reflected light, and cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging was carried out to identify the internal structures within zircons.

4.2 Microthermometry and composition of the fluid inclusion

Heating and cooling experiments were carried out using a Linkam THMSG-600 heating–freezing stage (−196 to +600°C) equipped with a Zeiss microscope at the Resources Exploration Laboratory, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, and the Xinjiang Key Laboratory for Geodynamic Processes and Metallogenic Prognosis of the CAOB, Xinjiang University, Urumqi. The stage was calibrated using synthetic fluid inclusions. The heating rate was 0.1 to 1°C/min below 10°C, whereas rates were about 3–5°C/min between 10 and 31°C, with a reproducibility of ±0.1°C. The heating rate was 5–10°C/min at higher temperatures (>100°C), with a reproducibility of ±2°C. Salinities of fluid inclusions were estimated using the reference data of Bodnar (1993) for the NaCl−H2O system. Salinities of three–phase CO2 type inclusions were estimated using the equations of Darling (1991) for the CO2–NaCl–H2O system.

The gas and liquid composition of fluid inclusions were completed at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing. Gas analysis instrument is Prisma TM QMS200 Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer according to the method of Zhu and Wang (2001). The dried washed sample weighing 50 mg was put in a clean quartz tube, and heated to 100°C. Then, valve was turned on and the gas pipe was vacuumed. When the pressure in the quartz tube was less than 6 × 10−6 Pa, the burst stove was heated to 550°C at the speed of 1°C/3 s. The vacuum valve was turned on for determination of gaseous composition. The liquid composition was analysed using HIC-6A Ion Chromatograph. Similarly, put the cleaned sample into a quartz tube and burst for 15 minutes when the temperature is raised to 500°C. Add 5 mL of water after cooling and ultrasonically vibrate for 10 minutes before measuring.

4.3 Hydrogen, oxygen, and sulphur isotope analysis

Hydrogen, oxygen and sulphur isotope analyses were performed using a Finningan MAT 253 EM mass spectrometer at the Analytical Laboratory of the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology, China. All mineral separates were examined using a binocular microscope prior to isotope analysis to ensure 99% purity. Oxygen isotopic analysis was undertaken using the BrF5 method (Clayton & Mayeda, 1963). δDV-SMOW values were measured on water in fluid inclusions which was released by the thermal decrepitation method, this water was then reacted with zinc for 30 min at a temperature of 400°C to produce hydrogen (Coleman, Sheppard, Durham, Rouse, & Moore, 1982), which was collected in sample tubes with activated charcoal at liquid N2 temperatures (Mao et al., 2002). The isotopic data were reported relative to the Standard Mean Ocean Water (SMOW) standard for δ18OV-SMOW and δDV-SMOW. Cu2O was used as the oxidizer for the preparation of sulphide samples (Robinson & Kusakabe, 1975). Sulphate minerals were purified to pure BaSO4 using the carbonate–zinc oxide semi–melt method, then SO2 was prepared using V2O5 oxide and Cu2O method, and the SO2 was used for sulphur isotopes analysis. The analytical uncertainty was ±0.2‰ for oxygen and sulphur isotope analyses, and ± 2‰ for hydrogen isotope analysis.

4.4 Zircon U–Pb dating

U–Pb dating was completed by a sensitive high-resolution laser ablation multi-collector inductively-coupled plasma source mass spectrometer (Analytikjena PlasmaQuant MS Elite ICP-MS) composed of an ESI NWR 193nm FX laser and a Neptune mass spectrometer at the Beijing Createch Testing Technology Co., Ltd, China. Details of the analytical procedures are described in the work of Yuan et al. (2010). The final test data were processed with ICP-MS DataCal (Liu et al., 2008) and ISOPLOT 3.70 (Ludwig, 2008).

5 ANALYTICAL RESULTS

5.1 Fluid inclusion study

5.1.1 Inclusion types and characteristics

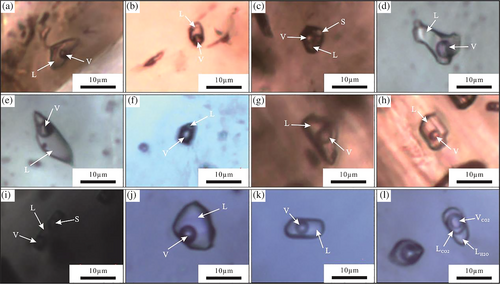

The observed fluid inclusions include primary, pseudosecondary, and secondary inclusions. Primary inclusions are isolated or distributed along crystal belts, pseudosecondary inclusions are distributed along the healing cracks inside a crystal, the secondary inclusions are distributed along the healing cracks between different crystals. According to the physical phase and chemical composition of the inclusions at room temperature, the primary and pseudosecondary fluid inclusions (research target) can be classified into H2O–NaCl and H2O–CO2 (±CH4/N2)–NaCl types. The H2O–NaCl fluid inclusions can be further divided into liquid, vapour, and daughter mineral-bearing polyphase inclusions (Lu et al., 2004). The H2O–CO2 (±CH4/N2)–NaCl fluid inclusions occur as three-phase CO2-type inclusions. These types of inclusions and their characteristics are listed in Table 1 and shown in Figure 9.

| Stage | Mineral | Type | Te (°C) | Tmcla (°C) | ThCO2 (°C) | Th (°C) | Tmice (°C) | Salinity (wt% NaCleq) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | Range | Mean | |||||||

I prograde skarn stage |

Garnet | Liquid type | −24.0 to −23.0 | 243–480(96) | 316 | −10.1 to −1.3 | 2.24–14.04(89) | 8.04 | ||

| Daughter mineral–bearing polyphase inclusions | 298–312 (2) * | 305 | −4.6 to −3.2 | 5.26–7.31 (2) | 6.29 | |||||

| Diopside | Liquid type | −24.2 to −21.8 | 211–377 (60) | 270 | −5.4 to– 2.8 | 4.65–8.41 (55) | 7.00 | |||

| Vapour type | 262 (1) | 262 | ||||||||

II retrograde skarn stage |

Epidote | Liquid type | −23.5 to −22.1 | 178–336 (75) | 250 | −6.2 to −3.0 | 4.96–9.47 (77) | 7.58 | ||

| Daughter mineral–bearing polyphase inclusions | 258–269 (4) * | 265 | −5.4 to −3.9 | 6.30–8.41 (4) | 7.54 | |||||

III quartz–sulphide stage |

Quartz | Liquid type | −25.6 to −21.5 | 130–326 (55) | 224 | −5.8 to −0.8 | 1.40–8.95 (55) | 4.24 | ||

| Three–phase CO2 type | −61.9 to −58.4 | 4.6–6.5 (17) | 15–25 | 258–363 (17) * | 291 | 6.60–9.60 (17) | 8.26 | |||

| Vapour type | 297–434 (2) | 366 | −2.8 to −2.2 | 3.71–4.65 (2) | 4.18 | |||||

- Note: Te—eutectic melting temperature Tmcla—melting temperature of CO2 clathrate; ThCO2—partial homogenization temperature of CO2 into liquid; Th—total homogenization temperature; Tmice—final ice melting temperature; *—disappear temperature of vapour; (17)—the number of inclusions.

Fluid inclusions in the garnet and diopside of stage I are mainly liquid type, mostly irregular and elliptical in shape. Their sizes are mostly 2 × 3 to 5 × 6 μm2, with a maximum of 10 × 40 μm2, and they contain 5–40 vol% vapour with the minority containing 50%. Only two daughter mineral-bearing (irregular or nearly round transparent crystals) polyphase inclusions are found in the garnet, which are 6 × 8 μm2 and 6 × 7 μm2 in size, irregular and elliptical in shape, and the inclusion contains 10 vol% vapour. And one vapour inclusion in diopside has a size of 4 × 6 μm and contains 60 vol% vapour.

Inclusions in the epidote of stage II are dominantly liquid inclusions, mostly irregular and elliptical in shape, primarily 2 × 3 to 5 × 6 μm2 in size with a maximum size of 16 × 28 μm2, and contain 5–30 vol% vapour. Only four daughter mineral-bearing (irregular or nearly round transparent crystals) polyphase inclusions were found, which are irregular and elliptical in shape, range in size from 3 × 7 to 6 × 12 μm2 and contain 10 vol% vapour.

Fluid inclusions in the quartz of stage III are mainly liquid inclusions and three-phase CO2-type inclusions, and a small number are vapour inclusions. The sizes of the liquid inclusions are mainly 2 × 2.4 to 3.5 × 8 μm2, and the maximum is 6 × 13 μm2; they are mostly irregular, nearly round, and elliptical in shape, and contain 15–50 vol% vapour. The three-phase CO2-type inclusions coexist with a portion of liquid type, are composed of vapour carbon dioxide (VCO2), liquid carbon dioxide (LCO2), and aqueous (LH2O) phases; mostly are nearly round and elliptical in shape, 3 × 5 to 7.5 × 8 μm2 in size, and contain 25–70 vol% vapour. The inclusions have two phases (VCO2 and LH2O) at room temperature, but three phases appear after cooling. Only two vapour inclusions are found in quartz, they are 7 × 9.6 μm2 and 6 × 10 μm2 in size and are irregular in shape. The rare vapour type and daughter mineral-bearing polyphase inclusions in minerals existed independently or distributed around the liquid-type inclusions, and there is no symbol of boiling.

5.1.2 Microthermometry results

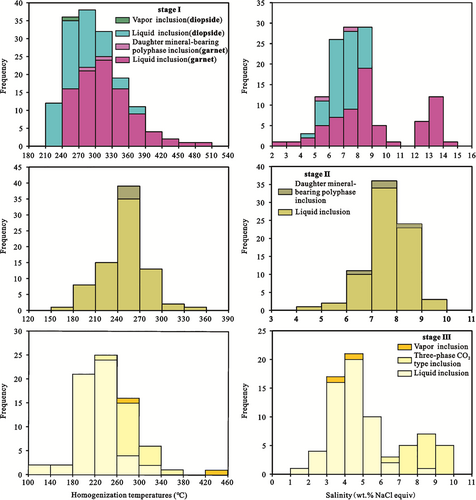

Fluid inclusions in 19 samples from the prograde skarn stage (I), the retrograde skarn stage (II), and the quartz–sulphide stage (III) were measured, and the results are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 10.

The homogenization temperatures (Th) of the liquid inclusions in garnet are highly variable, ranging from 243 to 480°C, with a peak value of 315°C. Fluid is dominated by NaCl according to the eutectic melting temperatures of −24.0 to −23.0°C (Crawford, 1981). The final ice melting temperatures for these inclusions range from −10.1 to −1.3°C, and the salinities range from 2.24 to 14.04 wt% NaCl equiv (Bodnar, 1993) with a peak at 8.50 wt% NaCl equiv (Figure 10). The Th of the two daughter mineral–bearing polyphase inclusions is >600°C, and all bubbles disappear at 298 to 312°C before the crystals disappear. According to the relationship between the salinity and the final ice melting temperatures, the salinity is 5.26 to 7.31 wt% NaCl equiv. The Th values of the liquid inclusions in diopside range from 211 to 377°C with a peak at 255°C, and the final ice melting temperatures vary from −5.4 to −2.8°C. The salinities vary from 4.65 to 8.41 wt% NaCl equiv with a peak value of 7.00 wt% NaCl equiv. Fluid is dominated by NaCl according to the eutectic melting temperatures of −24.2 to −21.8°C (Crawford, 1981). The Th value of one vapour inclusion is 262°C.

The Th of the liquid inclusions in the epidote from stage II ranges between 178 and 336°C with a peak temperature of 255°C. The salinities of the liquid inclusions determined from the final ice melting temperatures of −6.2 to −3.0°C range from 4.96 to 9.47 wt% NaCl equiv. Fluid is dominated by NaCl according to the eutectic melting temperatures of −23.5 to −22.1°C (Crawford, 1981). The Th of the four daughter mineral-bearing polyphase inclusions is >600°C, and all bubbles disappear at 258 to 269°C before the crystals disappear, and the salinity is 6.30 to 8.41 wt% NaCl equiv.

The Th of the liquid inclusions in quartz from stage III range from 130 to 326°C, the final ice melting temperatures range from −5.8 to −0.8°C, and the salinity ranges from 1.40 to 8.95 wt% NaCl equiv. Fluid is dominated by NaCl according to the eutectic melting temperatures of −25.6 to −21.5°C (Crawford, 1981). The Th of the three-phase CO2-type inclusions is concentrated at 258 to 363°C, and it homogenizes to the vapour phase, indicating that the fluid is gaseous when captured. The clathrate-melting temperatures are 4.6 to 6.5°C, and the partial homogenization temperature of LCO2 + VCO2 is between 15 and 25°C, which is lower than its standard temperature of 31.1°C, and the salinity is mainly 6.60 to 9.60 wt% NaCl equiv. The Th of the two vapour inclusions ranges from 297 to 434°C, the final ice melting temperatures range from −2.8 to −2.2°C, and the salinity ranges from 3.71 to 4.65 wt% NaCl equiv.

In summary, all the Th of the daughter mineral–bearing polyphase inclusions is >600°C, greater than the detection limit of the instrument, and all bubbles disappear before the daughter mineral. In addition, the liquid-type inclusions did not detect high salinity, indicating that solids are not precipitated from a high salinity fluid on cooling. This article believes that the daughter minerals are occasionally captured solids (irregular or nearly round transparent crystals), and further research is needed for their compositions.

5.1.3 Compositions of the inclusions

The components of four quartz samples from stage III are listed in Table 2.

| Ser No. | Sample No. | Na+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | F− | Cl− | SO42− | CH4 | C2H6 | CO2 | H2O | H2S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BSTLK16–2 | 2.03 | 0.204 | 1.54 | 6.9 | 0.636 | 0.714 | — | 35.55 | 7.785 | 56.6 | 0.005 |

| 2 | BSTLK16–12 | 2.03 | 0.153 | 0.672 | — | 0.564 | 0.342 | 2.131 | 16.57 | 33.26 | 45.26 | 0.03 |

| 3 | BSTLK16–23 | 5.52 | 0.051 | 0.48 | — | 0.516 | 1.03 | 2.768 | 3.259 | 7.677 | 83.17 | 0.007 |

| 4 | BSTLK16–27 | 4.38 | 0.051 | 0.384 | — | 0.516 | 0.687 |

- Note: — means lower than detecting limit.

The cations in the liquid phase of the fluid inclusions are mainly Na+ (2.03–5.52 μg/g) and Ca+ (0.384–1.54 μg/g), followed by Mg2+ (0.051–0.204 μg/g), and the K+ concentration is below the detection limit. The anions are mainly Cl− (0.516–0.636 μg/g) and SO42− (0.342–1.03 μg/g); only one sample had a F− concentration of 6.9 μg/g, but the concentrations in the other three samples were below the detection limit.

The vapour phase components of the fluid inclusions are mainly H2O (45.26–83.17 μg/g), C2H6 (3.259–35.55 μg/g), and CO2 (7.677–33.26 μg/g), followed by CH4 (2.131–2.768 μg/g), and a small amount of H2S (0.007–0.03 μg/g).

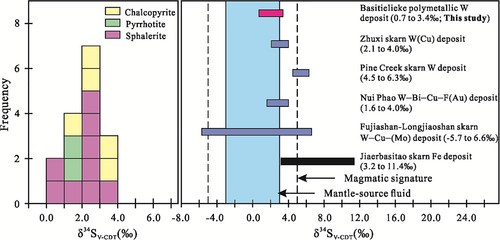

5.2 Sulphur isotope composition

The sulphur isotopic compositions of 16 samples from the Basitielieke deposit are listed in Table 3, and the δ34SV-CDT values are in the range of 0.7–3.4‰ with a mean of 2.26‰. Different sulphides have varying δ34SV-CDT values: the δ34SV-CDT values of nine sphalerite samples range from 0.7 to 3.4‰ with a mean of 2.1‰, the δ34SV-CDT values of two pyrrhotite samples range from 1.2 to 1.8‰ with a mean of 1.5‰, and the δ34SV-CDT values of five chalcopyrite samples range from 2.0 to 3.4‰ with a mean of 2.84‰.

| Ser.No. | Sample No. | Mineral | δ34SV-CDT (‰) | Ser.No. | Sample No. | Mineral | δ34SV-CDT (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BSTLK16–1 | Sphalerite | 1.1 | 9 | BSTLK16–34 | Sphalerite | 0.7 |

| 2 | BSTLK16–3 | Sphalerite | 1.0 | 10 | BSTLK16–24 | Pyrrhotite | 1.8 |

| 3 | BSTLK16–9 | Sphalerite | 2.1 | 11 | BSTLK16–6 | Pyrrhotite | 1.2 |

| 4 | BSTLK16–11 | Sphalerite | 2.7 | 12 | BSTLK16–16 | Chalcopyrite | 2.7 |

| 5 | BSTLK16–14 | Sphalerite | 3.4 | 13 | BSTLK16–8 | Chalcopyrite | 3.4 |

| 6 | BSTLK16–15 | Sphalerite | 2.5 | 14 | BSTLK16–25 | Chalcopyrite | 3.0 |

| 7 | BSTLK16–29 | Sphalerite | 3.0 | 15 | BSTLK16–28 | Chalcopyrite | 2.0 |

| 8 | BSTLK16–30–1 | Sphalerite | 2.4 | 16 | BSTLK16–30–2 | Chalcopyrite | 3.1 |

5.3 Hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes

The hydrogen and oxygen isotope compositions of samples from stages I and III in the Basitielieke deposit are shown in Table 4.

| Ser.No. | Sample No. | Mineral | δ18OV-SMOW (‰) | Temperature (°C) | δ18Ofluid(‰) | δDV-SMOW (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BSTLK16–2 | Quartz | 13.7 | 308 | 7.09 | −103.8 |

| 2 | BSTLK16–12 | Quartz | 14.3 | 322 | 8.16 | −110.5 |

| 3 | BSTLK16–23 | Quartz | 12.5 | 337 | 6.82 | −108.5 |

| 4 | BSTLK16–27 | Quartz | 12.5 | 348 | 7.14 | −101.4 |

| 5 | BSTLK16–40 | Quartz | 9.7 | 328 | 3.75 | −77.1 |

| 6 | BSTLK16–46 | Quartz | 10.5 | 351 | 5.22 | −84.5 |

| 7 | BSTLK16–38 | Garnet | 7.9 | 450 | 10.45 | −86.0 |

| 8 | BSTLK16–41 | Garnet | 6.9 | 450 | 9.45 | −84.1 |

| 9 | BSTLK16–44 | Garnet | 8.7 | 450 | 11.25 | −85.1 |

The δDV-SMOW values of three garnet samples range from −86 to −84‰, and the δ18OV-SMOW values fall in a consistently narrow range from 6.9 to 8.7‰. Using the garnet–water fractionation equation, 1000lnα = 1.22 × 106 T−2–4.88 (Taylor, 1974), and the average homogenization temperature after correction of fluid inclusions in the same sample, the δ18Ofluid values of the ore-forming fluids are calculated to be 9.45 to 11.25‰.

The δDV-SMOW values of six quartz samples vary from −110 to −77‰, and δ18OV-SMOW values range from 9.7 to 14.3‰. Using the quartz–water fractionation equation, 1000lnα = 3.38 × 106 T−2–3.40 (Clayton, O'Neil, & Mayeda, 1972), and the average homogenization temperature after correction of fluid inclusions in quartz in the same sample, the δ18Ofluid values of the ore-forming fluids are calculated to be 3.75 to 8.16‰.

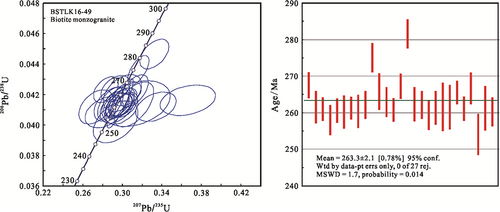

5.4 Zircon U–Pb geochronology

The results of zircon U–Pb dating for sample (BSTLK16-49) are shown in Table 5. Zircons separated from the sample are mostly hypidiomorphic-idiomorphic, long or short columnar crystals in shape. The length of the long axis is between 80 and 200 μm, and the ratio of length/width between 1.5:1 and 2.5:1. It can be seen in the CL image that most zircons have obvious oscillatory zone structures. The Th and U contents of the zircons exhibit a wide variation, with the Th contents ranging from 36.01 × 10−6 to 471.34 × 10−6, and U from 81.22 × 10−6 to 1,980.43 × 10−6. The Th/U ratios are between 0.09 and 0.99, indicating that zircon has magmatic origin (Belousova, Griffin, O'Reilly, & Fisher, 2002). A total number of 27 analyses have consistent 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U ratios within the analytical precision, yielding a cluster of concordant data points (Figure 11) and a weighted mean age of 263.3 ± 2.1 Ma (MSWD = 1.7), which could represent the age of the biotite monzogranite.

| Dot. no. | Content (10−6) | Th/U | Isotope ratios | Ages (Ma) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Th | U | 207Pb/ | 1σ | 207Pb/ | 1σ | 206Pb/ | 1σ | 207Pb/ | 1σ | 207Pb/ | 1σ | 206Pb/ | 1σ | ||

| 206Pb | 235U | 238U | 206Pb | 235U | 238U | |||||||||||

| BSTLK16–49–1 | 33.2 | 158.9 | 733.2 | 0.22 | 0.0500 | 0.0015 | 0.2933 | 0.0097 | 0.0424 | 0.0006 | 194.5 | 70.4 | 194.5 | 70.4 | 267.5 | 3.5 |

| BSTLK16–49–2 | 32.1 | 105.7 | 746.1 | 0.14 | 0.0504 | 0.0014 | 0.2881 | 0.0086 | 0.0414 | 0.0007 | 213.0 | 63.0 | 213.0 | 63.0 | 261.5 | 4.4 |

| BSTLK16–49–3 | 23.2 | 119.1 | 521.0 | 0.23 | 0.0515 | 0.0014 | 0.2942 | 0.0087 | 0.0413 | 0.0005 | 261.2 | 61.1 | 261.2 | 61.1 | 261.0 | 3.2 |

| BSTLK16–49–4 | 8.6 | 113.2 | 170.4 | 0.66 | 0.0504 | 0.0023 | 0.2817 | 0.0127 | 0.0408 | 0.0007 | 213.0 | 105.5 | 213.0 | 105.5 | 258.0 | 4.1 |

| BSTLK16–49–5 | 21.1 | 108.1 | 479.8 | 0.23 | 0.0524 | 0.0016 | 0.2966 | 0.0090 | 0.0413 | 0.0005 | 301.9 | 72.2 | 301.9 | 72.2 | 260.6 | 3.3 |

| BSTLK16–49–6 | 12.9 | 240.6 | 243.5 | 0.99 | 0.0487 | 0.0021 | 0.2734 | 0.0114 | 0.0412 | 0.0007 | 200.1 | 103.7 | 200.1 | 103.7 | 260.2 | 4.6 |

| BSTLK16–49–7 | 48.99 | 115.2 | 1,141.5 | 0.10 | 0.0526 | 0.0013 | 0.2997 | 0.0076 | 0.0414 | 0.0005 | 309.3 | 55.6 | 309.3 | 55.6 | 261.2 | 3.1 |

| BSTLK16–49–8 | 11.1 | 36.0 | 247.8 | 0.15 | 0.0522 | 0.0020 | 0.2951 | 0.0116 | 0.0412 | 0.0007 | 294.5 | 88.9 | 294.5 | 88.9 | 260.3 | 4.5 |

| BSTLK16–49–9 | 25.9 | 96.7 | 582.8 | 0.17 | 0.0531 | 0.0018 | 0.3008 | 0.0093 | 0.0415 | 0.0006 | 331.5 | 77.8 | 331.5 | 77.8 | 262.1 | 3.8 |

| BSTLK16–49–10 | 90.4 | 291.1 | 1980.4 | 0.15 | 0.0529 | 0.0013 | 0.3161 | 0.0072 | 0.0436 | 0.0006 | 324.1 | 27.8 | 324.1 | 27.8 | 275.0 | 4.0 |

| BSTLK16–49–11 | 11.9 | 66.8 | 258.5 | 0.26 | 0.0521 | 0.0021 | 0.3002 | 0.0128 | 0.0421 | 0.0008 | 300.1 | 97.2 | 300.1 | 97.2 | 265.8 | 4.9 |

| BSTLK16–49–12 | 35.6 | 471.3 | 685.4 | 0.69 | 0.0632 | 0.0028 | 0.3662 | 0.0185 | 0.0416 | 0.0007 | 716.7 | 92.6 | 716.7 | 92.6 | 262.9 | 4.1 |

| BSTLK16–49–13 | 32.1 | 121.5 | 716.4 | 0.17 | 0.0522 | 0.0015 | 0.2964 | 0.0087 | 0.0413 | 0.0005 | 294.5 | 66.7 | 294.5 | 66.7 | 260.8 | 3.2 |

| BSTLK16–49–14 | 30.1 | 88.4 | 658.9 | 0.13 | 0.0486 | 0.0014 | 0.2835 | 0.0082 | 0.0423 | 0.0006 | 131.6 | 66.7 | 131.6 | 66.7 | 267.2 | 3.4 |

| BSTLK16–49–15 | 42.6 | 107.8 | 880.4 | 0.12 | 0.0543 | 0.0016 | 0.3324 | 0.0097 | 0.0447 | 0.0006 | 383.4 | 66.7 | 383.4 | 66.7 | 281.6 | 4.0 |

| BSTLK16–49–16 | 25.4 | 92.8 | 563.8 | 0.16 | 0.0520 | 0.0015 | 0.2954 | 0.0080 | 0.0415 | 0.0008 | 287.1 | 64.8 | 287.1 | 64.8 | 262.3 | 4.7 |

| BSTLK16–49–17 | 24.7 | 107.7 | 536.8 | 0.20 | 0.0528 | 0.0017 | 0.2994 | 0.0087 | 0.0415 | 0.0006 | 320.4 | 67.6 | 320.4 | 67.6 | 262.1 | 3.8 |

| BSTLK16–49–18 | 23.4 | 101.5 | 515.6 | 0.20 | 0.0526 | 0.0016 | 0.2990 | 0.0111 | 0.0410 | 0.0006 | 322.3 | 73.1 | 322.3 | 73.1 | 259.3 | 4.0 |

| BSTLK16–49–19 | 9.7 | 95.4 | 200.2 | 0.48 | 0.0514 | 0.0023 | 0.2891 | 0.0116 | 0.0414 | 0.0007 | 261.2 | 106.5 | 261.2 | 106.5 | 261.3 | 4.6 |

| BSTLK16–49–20 | 46.2 | 91.6 | 1,017.7 | 0.09 | 0.0526 | 0.0017 | 0.2979 | 0.0087 | 0.0414 | 0.0011 | 322.3 | 74.1 | 322.3 | 74.1 | 261.6 | 6.6 |

| BSTLK16–49–21 | 4.04 | 38.5 | 81.2 | 0.47 | 0.0561 | 0.0045 | 0.3139 | 0.0228 | 0.0414 | 0.0010 | 457.5 | 181.5 | 457.5 | 181.5 | 261.5 | 6.1 |

| BSTLK16–49–22 | 29.92 | 73.3 | 653.2 | 0.11 | 0.0526 | 0.0016 | 0.3050 | 0.0093 | 0.0420 | 0.0005 | 309.3 | 75.0 | 309.3 | 75.0 | 265.5 | 3.2 |

| BSTLK16–49–23 | 27.9 | 111.6 | 606.3 | 0.18 | 0.0531 | 0.0014 | 0.3031 | 0.0081 | 0.0413 | 0.0005 | 344.5 | 59.3 | 344.5 | 59.3 | 261.1 | 3.3 |

| BSTLK16–49–24 | 20.2 | 48.3 | 440.1 | 0.11 | 0.0539 | 0.0017 | 0.3121 | 0.0094 | 0.0422 | 0.0007 | 368.6 | 70.4 | 368.6 | 70.4 | 266.6 | 4.3 |

| BSTLK16–49–25 | 10.8 | 98.7 | 226.8 | 0.44 | 0.0530 | 0.0028 | 0.2933 | 0.0149 | 0.0402 | 0.0009 | 331.5 | 116.7 | 331.5 | 116.7 | 254.1 | 5.6 |

| BSTLK16–49–26 | 23.9 | 297.7 | 469.1 | 0.63 | 0.0548 | 0.0018 | 0.3118 | 0.0132 | 0.0413 | 0.0010 | 405.6 | 74.1 | 405.6 | 74.1 | 261.2 | 6.0 |

| BSTLK16–49–27 | 14.5 | 56.6 | 306.0 | 0.18 | 0.0596 | 0.0026 | 0.3339 | 0.0135 | 0.0412 | 0.0006 | 587.1 | 89.8 | 587.1 | 89.8 | 260.3 | 3.9 |

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 Mineralization age of the Basitielieke deposit

The zircon U–Pb weighted average age is 275.4 ± 2.6 Ma (LA–Q–ICP–MS, Yang et al., 2019) from the pegmatite dyke that cuts through the orebody, this age, which belongs to the Early Permian, means that metallogenesis predates 275 Ma. Four molybdenite samples from the ore give a Re–Os isochron age and a weighted average age of 284.4 ± 5.5 Ma and 283.6 ± 2.1 Ma, respectively, indicating that Cu–Zn–Au mineralization occurred at 284 Ma and W mineralization occurred slightly earlier than 284 Ma (Yang et al., 2019). The biotite monzogranite sample (BSTLK16-49) taken from the Basitielieke ore block yielded a U–Pb weighted average age of 263.3 ± 2.1 Ma (this study), which is less than 21 Ma from the mineralization age. Moreover, biotite monzogranite has a fault contact with the Kangbutiebao Formation, and there is no skarn in the contact zone. Based on these factors, it is believed that biotite monzogranite does not contribute to the polymetallic mineralization of the Basitielieke deposit.

The Kslgui biotite monzogranite stock is exposed approximately 4 km west of the East Basitielieke ore block (Figure 2). Its zircon SHRIMP U–Pb age is 286.6 ± 2.6 Ma (Liu, Zhang, & Yang, 2012), which is consistent (within the error range) with the metallogenic age of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit. The Jiaerbasitao skarn iron deposit (Liu, Zhang, & Yang, 2012; Yang, Wang, Yang, Li, & Guo, 2018) is produced in the contact zone of the Kslgui biotite monzogranite and marble, indicating that this geological environment has both the conditions and the capacity to form deposits in this area. According to research on the Jiaerbasitao deposit (Liu, Zhang, & Yang, 2012), these two deposits also are similar in terms of their fluid inclusions and isotopes.

In summary, experimental results show that the Basitielieke deposit is related to the skarn formed by the interaction of magmatic hydrothermal fluid from the Kslgui biotite monzogranite (or granite dikes contemporaneous with the Kslgui pluton in the Basitielieke ore district) and Kangbutiebao Formation in the Early Permian.

6.2 Nature and evolution of the fluid

Fluids play an extremely important role in the evolution of the crust and its geological processes, and petrology, ore deposit, and geochemical problems can be solved by analysing fluid inclusions, which can represent rocks and ore-forming environments (Lu et al., 2004). Various types of fluid inclusions are found in minerals of different mineralization stages from the Basitielieke deposit, providing evidence for analysing the nature and evolution of the fluid system (Roedder, 1984). Combined with geology, petrography, microthermometry, and fluid inclusion compositions, this study suggests that the ore-forming fluid related to the Basitielieke deposit can be divided into a H2O–NaCl system (the prograde skarn stage and the retrograde skarn stage) and a H2O–CO2 (±CH4/N2)–NaCl system (the quartz–sulphide stage).

The homogenization temperatures and salinities of fluid inclusions in stage I range from 211 to 480°C (with a peak value of 285°C) and from 2.24 to 14.04 wt% NaCl equiv (with peak values of 13.50 wt% NaCl equiv and 8.00 wt% NaCl equiv), respectively, indicating that the fluid was a moderate to higher temperature and moderate to lower salinity H2O–NaCl system. The homogenization temperature ranges from 178 to 336°C (with a peak value of 255 °C), and the salinities range from 4.96 to 9.47 wt% NaCl equiv with a peak value of 7.5 wt% NaCl equiv in the retrograde skarn stage (stage II, which is the main stage of W mineralization). Compared with the prograde skarn stage, the homogenization temperature decreases and the salinities remain largely unchanged, indicating that the fluid experienced simple cooling (Ni et al., 2015), and the change in salinity was not responsible for ore formation.

The most significant difference from stages I and II is the appearance of three-phase CO2-type inclusions in stage III. The homogenization temperature ranges from 130 to 434°C (with a peak value of 240°C), and the salinities range from 1.40 to 9.60 wt% NaCl equiv with a peak value of 4.5 wt% NaCl equiv. Changes in the temperature and salinity may be related to the addition of atmospheric water.

6.3 Source of the ore-forming fluid and material

The origin and history of H2O in hydrothermal fluids can be determined by hydrogen and oxygen isotopes (Taylor, 1997). The δDV-SMOW and δ18Ofluid values of fluids in the garnet of stage I at the Basitielieke deposit are concentrated under the region of magmatic water in the δDV-SMOW versus δ18Ofluid diagram (Figure 12), which indicates that magmatic water participated in the hydrothermal mineralization system in stage I. The δDV-SMOW and δ18Ofluid isotopic compositions of quartz (δDV-SMOW = −110.5 to −77.1‰; δ18Ofluid = 3.75 to 8.16‰) from stage III are closer to the meteoric water line, implying a significant involvement of meteoric water in the hydrothermal mineralization system, which is not an exception. For skarn-type tungsten deposits, most scholars believe that fluid systems contain both magmatic water and meteoric water (Brown, Bowman, & Kelly, 1985; Nie et al., 2019; Taylor & O'Meil, 1977; Zaw & Singoyi, 2000).

Sulphur isotopes can be used to identify the sources of sulphur and metallogenic elements in sulphur-bearing minerals within deposits (Ohmoto, 1972; Ohmoto & Goldhaber, 1997; Seal, 2006). The isotopic composition of sulphur in metal sulphides is controlled by the original material and physical–chemical conditions, including the f(O2), the pH value, and the temperature of the hydrothermal fluid (Ohmoto, 1972). Generally, the lack of sulphate in ores indicates that the δ34SV-CDT values of sulphide can represent the total sulphur value of the hydrothermal fluid (Dixon & Davidson, 1996; Ohmoto & Goldhaber, 1997; Ohmoto & Rye, 1979), and the total sulphur value can be represented by the average δ34SV-CDT value of sulphur in the simple mineral assemblage (Ohmoto & Rye, 1979; Zheng & Chen, 2000). The sulphur isotopic values of sulphide minerals (Figure 13 and Table 3) from the Basitielieke deposit are between 0.7 and 3.4‰ with a mean of 2.26‰, similar to most magmatic hydrothermal deposits (+1 to +3‰, Hoefs, 2009). This means that the δ34SV-CDT value of the hydrothermal fluid is approximately 2.26‰, and the uniform and narrow δ34SV-CDT range indicates that the sulphur of the Basitielieke deposit was derived from deep-seated magmas (0 ± 3‰, Hoefs, 1997).

6.4 Redox conditions

Skarn tungsten deposits can be divided into two types: reduced and oxidized (Newberry & Einaudi, 1981). In oxidized skarn deposits, andradite is more abundant than pyroxene, scheelite is Mo-rich (Hsu, 1977; Hsu & Galli, 1973), and ferric Fe phases are more common than ferrous phases (Meinert, Dipple, & Nicolescu, 2005). Meanwhile, garnet is the dominant mineral, and there is also an abundance of haematite, magnetite, K-feldspar, and epidote (Newberry, 1983). The skarn assemblages of the Basitielieke deposit are dominated by pyroxene and lesser amounts of garnet and epidote; no haematite is found in fluid inclusions or mines. Although rare molybdenum were found, but the bright blue fluorescence of scheelite (Figure 8) suggests it is Mo-poor scheelite (Mo-rich scheelite has a yellow fluorescence, Greenwood, 1943). These characteristics suggest that skarn was formed in a reducing environment.

Redox condition can also be inferred from the ratios of Fe2+/Fe3+ in skarn minerals (Zaw & Singoyi, 2000). Oxidized skarns have relatively low Fe2+/Fe3+ ratios, whereas reduced skarns have relatively high Fe2+/Fe3+ ratios (Sato, 1980). Brown and Essene (1985) suggested that redox can only be calculated with garnet and pyroxene phases. The ratio of Fe2+/Fe3+garnet from the Basitielieke deposit is 18.8, and the ratio of Fe2+/Fe3+pyroxene is 9.3–16.3 (EMPA data, Zhang et al., 2019). The skarn and mineral features imply that the Basitielieke deposit should belong to a reduced skarn polymetallic tungsten deposit.

6.5 Temperature and pressure estimate

The temperature and pressure conditions can be estimated by petrologic data on hydrothermal alteration mineral paragenesis (Soloviev, Kryazhev, & Dvurechenskaya, 2020). The homogenization temperatures of liquid-type inclusions in minerals of prograde and retrograde stages (211–480°C and 178–336°C, respectively) are significantly lower than typical temperatures (600 ± 50°C and 450 ± 50°C, respectively; Einaudi, Meinert, & Newberry, 1981; Meinert, Hedenquist, Saton, & Matsuhisa, 2003; Meinert, Dipple, & Nicolescu, 2005). Measured temperatures lower than actual entrapment temperatures reflect a significant pressure during the prograde and retrograde skarn formation at the Basitielieke deposits (Soloviev & Kryazhev, 2018).

HOKIEFLINCS_H2O-NACL can be used for estimate the P–T conditions of fluid inclusions formed in the single-phase fluid based on either trapping P or T are known independently (Steele-Macinnis, Lecumberri-Sanchez, & Bodnar, 2012). Andradite-grossular garnet is stable at temperatures of >400°C (Johnson & Norton, 1985), whereas diopside to diopside-hedenbergite pyroxene is stable at >450°C (Gustafson, 1974). According to the temperatures of mineral deposition assumed at 450°C, the pressures are calculated to be 1–3 kbars (Steele-Macinnis, Lecumberri-Sanchez, & Bodnar, 2012), these pressures correspond to a depth of 4–12 km assuming lithostatic conditions (Fournier, 1999).

Amphibole is stable at temperatures of ~430–390°C in low-CO2 (XCO2 < 0.3) and 2 kbars of total pressure (Einaudi, Meinert, & Newberry, 1981), whereas epidote is stable at ~250°C under pressures of 2–3 kbars (Liou, 1993). The retrograde skarn stage take 350°C as actural trapping temperature for pressure correction evidenced by presence of amphibole and epidote. So, These estimates yield pressure of 1–2 kbars (Steele-Macinnis, Lecumberri-Sanchez, & Bodnar, 2012), which correspond to a depth of 4–8 km assuming lithostatic conditions (Fournier, 1999).

The fluid in stage III belong to the H2O–CO2 (± CH4/N2)–NaCl system. We obtained homogenization temperatures of 258–363°C from three-phase CO2 type type inclusions. Estimate pressures of 1.1–1.9 kbars (Flincor; Brown, 1989), which correspond to depths of 4.4–7.6 km assuming lithostatic conditions (Fournier, 1999). Due to P–T conditions close to the retrograde skarn stage, no pressure correction is necessary for the homogenization temperature of three-phase CO2 type inclusions. The CO2 component in the ore-forming fluid can improve the solubility and entrapment pressure of the fluid (Joyce & Holloway, 1993). We take 1,500 bars as actual trapping pressure for temperature correction for liquid-type inclusions used HOKIEFLINCS_H2O-NACL (Steele-Macinnis, Lecumberri-Sanchez, & Bodnar, 2012). Estimate temperatures of 211–483 (Mean = 329) °C. It can represent the P–T conditions in stage III, thus the mineralization depth of the Basitielieke deposit is not less than 4 km.

6.6 Ore precipitation mechanisms

Researchers have proposed many precipitation mechanisms for tungsten deposits, including fluid cooling (Ni et al., 2015; O'Reilly, Gallagher, & Feely, 1997), boiling (So & Yun, 1994; Zaw & Singoyi, 2000), mixing (such as the mixing of meteoric water with magmatic water) (Heinrich, 1990; Yokart, Barr, Williams-Jones, & Macdonald, 2003), and water–rock interaction (Lecumberri-Sanchez, Vieira, Heinrich, Pinto, & Walle, 2017). For a single deposit, the precipitation of tungsten minerals is usually controlled by multiple mechanisms (Clark, Kontak, & Farrar, 1990; Kelly & Rye, 1979; Li & Li, 2020; Seal, Clark, & Morrissy, 1987; Wang et al., 2017).

In the range of 100 to 500°C, the solubility of scheelite increases as the temperature decreases, implying that simple cooling may not be an effective mechanism for the formation of scheelite deposits (Foster, 1977; Wood & Samson, 2000). Generally, cooling only produces the precipitation of pyrite and quartz and cannot cause the precipitation of chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and galena (Spycher & Reed, 1989). This indicates that cooling is not the main precipitation mechanism of the Basitielieke deposit.

The symbols of boiling: (1) the existence of hydraulic–hydrothermal breccias (blasting breccias); (2) gas–liquid ratios of fluid inclusions from one stage having a wide range and the coexistence of pure vapour inclusions, vapour inclusions, and high-salinity inclusions; and (3) hydrothermal alteration from sericitization (top) to adularization (bottom) on the boiling surface (Hayba, Bethke, Healed, & Foley, 1985; Nie et al., 2019). Only inclusions that are formed at the same time with the same or similar homogenization temperature and that were homogenized to different phases can be regarded as boiling inclusions (Lu et al., 2004). Field geological surveys did not find these phenomena, and the fluid inclusions are different from typical boiling inclusions. These evidences indicate that no fluid boiling occurs at the Basitielieke deposit.

In addition to the high concentration of W in the hydrothermal fluid, the precipitation of tungsten minerals also requires sufficient Fe, Mn, and Ca. (Lecumberri-Sanchez, Vieira, Heinrich, Pinto, & Walle, 2017). Scheelite usually forms in the contact zone between igneous rocks and calcareous wallrock, and the wallrock provides calcium, especially skarn-type scheelite deposits (Gaspar & Inverno, 2000; Mao & Li, 1996; Wu, Wang, & Xiong, 2014), it can form Ca skarn at prograde skarn stage. Scheelite formed at retrograde skarn stage, the most important source of Ca at reduced W skarn deposit should be pyroxene replacement by amphibole (Soloviev & Kryazhev, 2018). The water–rock interaction is considered to be the key mechanism for the formation of tungsten deposits (Lecumberri-Sanchez, Vieira, Heinrich, Pinto, & Walle, 2017). Because of weak mixing and no boiling in fluid, water–rock interaction for scheelite in the Basitielieke deposit can be regarded as the most important metallogenic mechanism.

The most important mechanism of mineral precipitation in the majority of hydrothermal deposits is fluid boiling and fluid mixing (Skinner, 1979; Zhang, 1997), and they are considered to be the main reason for the formation of high-grade tungsten deposits (Korges, Weis, Lüders, & Laurent, 2017; Wei et al., 2012). As discussed earlier, fluid boiling is not the main precipitation mechanism of this deposit, but boiling facilitates mixing and circulation of low-temperature meteoric water (Fournier, 1999), which promotes mineral precipitation (Yokart, Barr, Williams-Jones, & Macdonald, 2003). Hydrogen and oxygen isotope studies show that the prograde skarn stage was dominated by magmatic water, and the quartz–sulphide stage was dominated by meteoric water, with some minor contributions from magmatic fluids (Figure 12). Fluid mixing may cause the ƒ(O2) and the pH to increase and temperature and Cl of the fluid to decrease (Linnen & Williams-Jones, 1994; Singoyi & Zaw, 2001; Wei et al., 2012). These factors would lead to the precipitation of ore-forming elements of the Basitielieke deposit. As discussed above, water–rock interaction and fluid mixing are the main precipitation mechanism of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit.

6.7 Comparisons to other tungsten deposits

From a global perspective, tungsten deposits are mainly distributed in the Circum-Pacific Belt, the north coast of the Mediterranean, the southern Urals, central and western Asia, and Xinjiang and Gansu provinces of China (Shi, Lin, & Zhang, 2009). The Chinese Altay and adjacent regions in the Russian and Mongolian Altay form a tungsten province within central Asia (Demin, 1993; Graupner et al., 1999; Ivanova, Maksimyuk, & Naumov, 1985).

There are many tungsten deposits in Altay, Mongolia, including the Khovd gol W deposit, the Khaalgat W deposit, the Ulaan uul W deposit, the Tsunkheg W deposit, and the Achit nuur W deposit (Graupner et al., 1999; Kempe & Belyatsky, 2000; Liu et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2020). The main genetic types of the deposits are quartz vein types and greisenization granite types (Shen, 2013). Russia also has reports on tungsten deposits in this area, such as the Kalguty Mo–W(Be) deposit (Gorny Altay) confined to the Kalguty multiphase granitoid massif of the Chindagatui complex intrusion (Borovikov, Goverdovskiy, Borisenko, Bryanskiy, & Shabalin, 2016).

The Chinese Altay located in Xinjiang, NW China, and the tungsten deposits in Xinjiang are mainly concentrated in the East Tianshan Orogenic Belt (the southern margin of the CAOB), such as the Xiaobaishitou W–(Mo) deposit (Deng et al., 2017; Li, Yang, & Zhang, 2020), the Heiyanshan W deposit (Chen, 2019), and the Shadong W deposit (Jiang et al., 2012; Tang, Dong, Tu, & Liu, 2017), but there are few publications concerning tungsten deposits in the Altay. The Xiaobaishitou and Heiyanshan deposits are two typical skarn deposits; the Basitielieke deposit as a skarn deposit has many similarities with the other deposits listed in terms of its characteristics and sources of ore-forming fluid, and magmatic water was gradually mixed with meteoric water (Chen, 2019; Li, Yang, & Zhang, 2020). However, these deposits are not all products of the same period; the Xiaobaishitou deposit formed in the Early Triassic (molybdenite Re–Os, 253.0 ± 2.7 Ma, Li, Yang, Zhang, & Li, 2020), and the Heiyanhsan deposit formed in the Late Carboniferous (zircon U–Pb, 326.9 ± 1.6 Ma, Chen, 2019). Yang et al. (2020) summarized the characteristics and spatial and temporal distribution of Triassic deposits in the CAOB in Xinjiang and showed that granite pegmatite-type rare metal deposits are distributed in the Altay, while porphyry-type Mo deposits and skarn-type W and W (Mo) deposits are distributed in the East Tianshan.

The Zhongbao skarn W deposit and the Sangshuyuanzi skarn W deposit in the South Tianshan formed in the Early Permian (zircon U–Pb, 296 ± 4 Ma and 293 ± 3 Ma, LA-ICP-MS, Chen, Lü, Cao, Wu, & Zhu, 2013); similarly, the Basitielieke deposit formed in the Early Permian (Yang et al., 2019). The Late Carboniferous to Early Permian was an important metallogenic epoch for the CAOB, not only for W but also for other elements, such as in the Sarekoubu Au deposit (quartz Ar–Ar, 320 ± 6 Ma, Ding, Wang, Ma, Zhang, & Fang, 2001), the Xiaokalasu Li–Nb–Ta deposit (zircon U–Pb, 296.3 ± 9.0 Ma, LA-ICP-MS, Qin et al., 2013), the Duolanasayi Au deposit (muscovite Ar–Ar, 293.1 ± 4.8 Ma, Yan, Chen, Wang, Zhang, & Chen, 2004), the Jiaerbasitao Fe deposit (zircon U–Pb, 286.6 ± 2.6 Ma, SHRIMP, Liu, Zhang, & Yang, 2012), the Talate Li–Be–Nb–Ta deposit (muscovite Ar–Ar, 286.4 ± 1.6 Ma, Zhou, Qin, Tang, Wang, & Sakyi, 2016), and the Kuerqis Fe deposit (zircon U–Pb, 278.7 ± 0.94 Ma and 274.1 ± 1.1 Ma, LA-MC-ICP-MS, Zhang, Liu, & Yang, 2013). The Basitielieke deposit is the product of geological processes related to hydrothermal activity after the magmatic period.

7 CONCLUSIONS

- The Basitielieke deposit is a reduced skarn polymetallic tungsten deposit in Altay, Xinjiang. The mineralization can be divided into the skarn period and supergene oxidization period, the skarn period can be further divided into three stages: the prograde skarn stage (stage I), the retrograde skarn stage (stage II), and the quartz–sulphide stage (stage III). Scheelite precipitation occurred in stage II, while Cu–Zn–Au formed in stage III.

- The ore-forming fluid related to the Basitielieke deposit can be divided into H2O–NaCl systems including stage I (>450°C, 1–3 kbar, and 2.24 to 14.04 wt% NaCl equiv, after correction) and stage II (~350°C, 1–2 kbar, and 4.96 to 9.47 wt% NaCl equiv, after correction), and H2O–CO2 (±CH4/N2)–NaCl system in stage III (300 ± 50°C, ~1.5 kbar, and 1.40 to 9.60 wt% NaCl equiv, after correction). The mineralization depth of the Basitielieke deposit is not less than 4 km.

- H–O–S isotopes indicate that ore-forming fluid is dominated by magmatic water in stage I, and the content of meteoric water gradually increases with the ore-forming process. The water-rock interaction and fluid mixing are the main precipitation mechanism of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit. Ore-forming materials (metal and sulphur) are mainly derived from deep-seated magmas.

- The genesis of the Basitielieke polymetallic tungsten deposit is related to the same magmatic event as genesis of the Jiaerbasitao iron deposit. The deposit formed by hydrothermal fluid from the Kslgui biotite monzogranite, which interacted with strata and formed the deposit during the Early Permian.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was jointly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0601201) and Xinjiang Altay region resources compensation fund projects (Metallogenic regularity study and resource potential evaluation in the Kelan Basin, southern margin of Altay Mountains). We are grateful to Chengdong Yang, Yuchen Ren, Zhenhua Su and Kun Ma for their field work, and Laboratory staff for their laboratory assistance. We are also grateful to leaders and their colleagues from Geological and Mineral Prospecting Research Institute and No. 706 Geological Party, Nonferrous Geological Prospecting Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region for their field guidance and constructive discussions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data openly available in a public repository that issues datasets with DOIs.