Shale reservoir characterization and control factors on gas accumulation of the Lower Cambrian Niutitang shale, Sichuan Basin, South China

Abstract

The Lower Cambrian Niutitang shale is reported to be the oldest strata for large-scale shale gas reserves. Based on outcrop observations and laboratory analyses, this study used a comprehensive approach that integrated sedimentology, mineralogy, petrology, organic geochemistry, and reservoir geology to estimate the prospects for exploring for shale gas in the Lower Cambrian Niutitang Formation, southern China. Whole rock and clay mineral X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations, and petro-physical property measurements indicate that the Niutitang shale is dominated by quartz and clay minerals with minor amounts of plagioclase, potassium feldspar, calcite, dolomite, and pyrite. The organic matter in the Niutitang shale is dominated by type-1 kerogen, with TOC levels ranging from 1.35% to 14.3% (average 4.46%) and Ro values ranging from 1.86% to 4.18% (average 2.79%). The three primary types of pores in the shale are organic pores, microfractures, and micropores. The micropores are primarily found in the clay mineral crystals and pyrite, and the microfractures are found along the boundaries of quartz grains. Most of the pore diameters are less than 20 nm, mainly concentrate at about 10 nm, which is consistent with that the organic pores act as the main storage space. The pore volume and gas content are strongly controlled by the mineral composition and lithofacies, and TOC content. The factors favouring shale gas accumulation of the Niutitang shale in the study area include (1) an effective thickness and widespread distribution, (2) a high organic carbon content and appropriate organic matter maturity, and (3) a favourable depositional environment.

1 INTRODUCTION

With constantly increasing energy demands and the scarcity of conventional oil and gas, unconventional oil and gas, particularly shale oil and gas, have become an important exploration target around the world (Liang, Cao, Jiang, Wu, & Song, 2017; Liang et al., 2018; Montgomery, Jarvie, Bowker, & Pollastro, 2005; Scott & Glasspool, 2005). Shale gas is essentially continuous-type biogenic, thermogenic, or combined biogenic–thermogenic gas (Ross & Bustin, 2007), and shale gas systems are characterized by widespread gas saturation, subtle trapping mechanisms, seals of variable lithology, and relatively short hydrocarbon migration distances (Curtis, 2002; Jarvie, Hill, & Ruble, 2007). The natural gas stored in shale reservoirs occurs as three manners: (1) free gas in pores and fractures, (2) adsorbed gas in organic matter and inorganic minerals, and (3) dissolved gas in “in situ” liquid hydrocarbons (Ferrill, Morris, Hennings, & Haddad, 2014; Hao, Guo, & Zhu, 2008; Liang et al., 2016). The pore systems in the organic matter and inorganic grains of shale reservoirs are dominated by nanometre- to micrometre-scale pores (Yang, Ning, Wang, & Liu, 2016), which include pores associated with organic matter, interparticle pores, intraparticle pores, and microfractures (Liang, Jiang, Yang, & Wei, 2012; Loucks, Reed, Ruppel, & Hammes, 2012; Milliken, Rudnicki, Awwiller, & Zhang, 2013; Slatt & O'Brien, 2011). The evaluation factors of shale gas reservoirs include organic-rich shale thickness and depth, lithofacies, TOC content, organic matter type, porosity, permeability, gas content, and brittleness (Chalmers & Bustin, 2012; Chalmers, Bustin, & Power, 2012; Chen et al., 2014; Gasparik et al., 2014).

Shale gas exploration and development has been successful in the United States, whereas the study of shale gas in China is still in its infancy (Bowker, 2007; Guo, Jiang, Zhang, & Li, 2011; Liang et al., 2016). The black shale is widely distributed in many strata in various basins in China, and previous researches have shown that shale gas resources in China may total some 36 trillion cubic metres (data from EIA), which suggest the great potential for exploration and exploitation of shale gas (Liu, Ma, Huang, Zeng, & Zhang, 2011; Zou et al., 2010). The Sichuan Basin is the key area of the shale gas strategy experimental site, with two target intervals, the Lower Cambrian Niutitang Formation shale and the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation shale (Liang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2014).

China Geological Survey Bureau had a breakthrough for shale gas in the Niutitang shales in the North Guizhou province in 2016, suggesting that the Lower Cambrian shales have impressive shale gas exploration prospect, which will be the oldest strata reported for large-scale shale gas enrichment. The depositional environment and the source rock characteristics of the Niutitang Formation shale have been investigated in a few studies (Liang et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2016), which suggest that the Niutitang shale was mainly deposited in a shelf environment and acts as quality source rock. The reservoir characteristics of the shales and its controlling factors are not clear. This work focuses on the shale gas potential of the Niutitang shale in southeast Sichuan Basin. In this study, based on the outcrops, we focus on the lithologic characteristics, pore space, and reservoir physical properties of the Niutitang shale. Through this study, we expect to characterize the reservoir characteristics (mineralogy, lithology, organic material, porosity, etc.) and analyse the primary factors for the shale gas accumulation of the Niutitang shale.

2 GEOLOGICAL SETTING

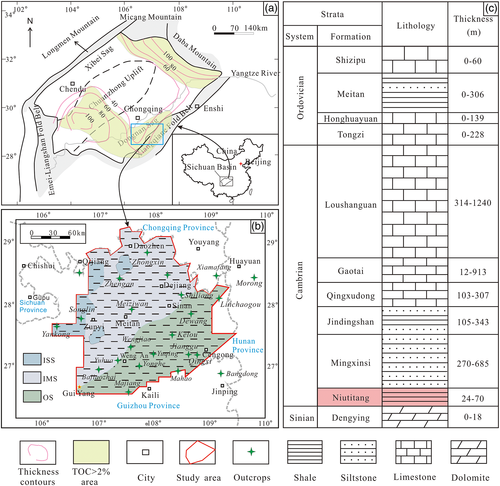

The study area is located in southeast Sichuan Basin, in an area which mainly includes northern Guizhou Province, southern China (Figure 1a,b). The effects of tectonic movements, folding and faulting, are well developed in northern Guizhou (Jiu et al., 2013; Li, Yu, & Guo, 2013). In general, the fold axes are primarily NE or NNE trending, and ancient fractures are widespread and well developed, resulting in a complex network of fault systems (Wu et al., 2014). The tectonic setting of the study area is primarily extensional, with a strike-slip component. Due to long-term mutual interference and superposition of various periods of tectonism, the current complex tectonic landscape of the combination of folds and faults was formed (Zeng et al., 2013).

The Sichuan Basin evolved from a Sinian (Z1)-Middle Triassic (T2) passive continental margin, during which thick marine carbonate and clastics interbedded with volcanic beds were deposited (Chen et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2014; Liu, Algeo, Guo, Fan, & Lu, 2017). The strata thickness is about 4,100–7,000 m. In the Late Triassic, the basin was affected by closure of the Palaeo-Tethys and the subduction of oceanic crust of the Yangtze Plate (Guo et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2012). The Jurassice-Quaternary was essentially a foreland basin stage with intense folding, uplift, and erosion. The Upper Triassic-Quaternary is mainly composed of continental strata with a thickness of 3,500–6,000 m (Mei, Zhang, Zhang, Meng, & Chen, 2006; Wu et al., 2014). The seafloor spreading leads to a rapid global sea-level rise, resulting in the Yangtze carbonate platform submerged (Michael, Wallis, & Erdtmann, 2001; Zhang & Zhu, 2006). Meanwhile, the rising of sea level forms a reducing environment, where the Niutitang Formation organic-rich black shale was deposited.

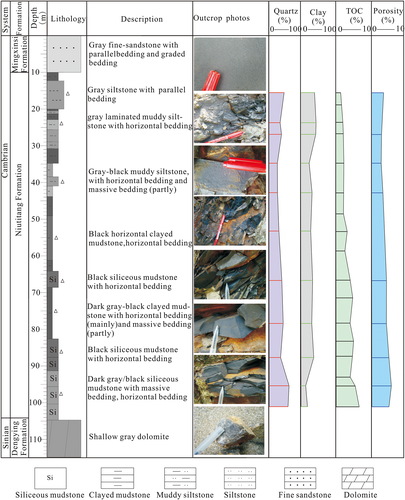

Thick sets of dolomite deposited during the Sinian period in the study area, above which were deposited the Lower Cambrian Niutitang Formation shale (Figure 1c). The Niutitang Formation shale is widespread and has considerable thickness, which is approximately up to 200 m, and portions of the organic-rich black shale are thicker than 50 m (Figure 1a). Studies show that the Niutitang Formation shale was mainly deposited in a shelf environment outer shelf, inner muddy shelf, and inner sandy shelf (Figure 1b). The sandstone of the Mingxinsi Formation overlie the Niutitang Formation shale (Figure 1c).

3 METHODS

This study used an approach that integrated sedimentology, mineralogy, petrology, and reservoir geology. Due to the study area is still in its early stage of exploration, no well has been drilled in the study area, and samples were collected from field outcrops. The basic data included 1,500 m of total outcrops in 12 profiles, 62 thin sections from outcrops samples, mineral composition data by X-ray diffraction from the 35 samples, source rock data (vitrinite reflectance, TOC, maceral composition) from 35 samples, and SEM observation of 28 samples, reservoir physical testing data of 19 samples. In this study, the selected outcrop profiles are mostly fresh sections excavated because of recent road building in the basin. In addition, we made every effort to excavate fresh samples and avoid weathered material during the sampling.

The thin sections observations were taken using a Zeiss microscope Axio Scope A1, and samples were prepared with a thickness of 0.03 mm. The mineral X-ray diffraction was performed using a D/max-2500 TTR. Prior to analysis, each sample was oven-dried at 40 °C for 2 days and ground to <40 μm using an agate mortar to thoroughly disperse the minerals. Computer analysis of the diffractograms enabled the identification and semi-quantitative analysis of the relative abundance (in weight per cent) of the various mineral phases.

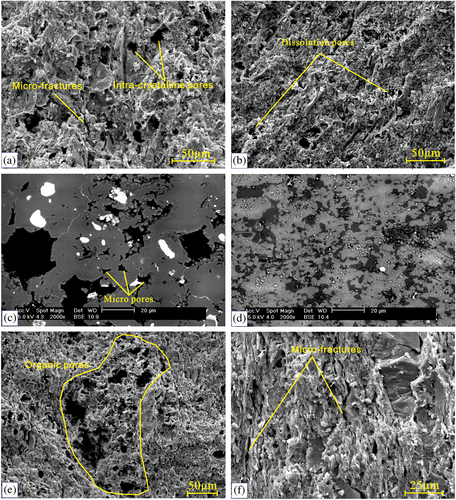

The source rock data (TOC, vitrinite reflectance, maceral composition) were obtained at the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Science, and test technique uses the method from Tissot and Welte, 1984. The organic carbon content was determined using a Leco carbon–sulphur analyser CS600 and gas-shows evaluation instrument. The test temperature was 27 °C. The measurement technique is based on the combustion of the sample in an oxygen atmosphere to convert the total organic carbon to CO2. The organic matter maturity and micro-component tests were performed using a LABORLUX 12POL fluorescence microscope and MPV-3 microscope photometer with a total magnification of 800 times. The vitrinite reflectance values were calculated using the formula:

(Zhang & Zhu, 2006), where BRo is bitumen reflectance.

(Zhang & Zhu, 2006), where BRo is bitumen reflectance.

The SEM observations and reservoir property analyses were detected using test equipment S-4800, with room temperature of 20 °C and relative humidity of 40%. The meso−macropore (>2 nm) volume and surface area were detected using nitrogen (N2) gas adsorption, which has been widely applied to characterize the nanopores in shales. The shale samples were first crushed into mesh grains and then dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 100 °C to remove the residual water and other gases. The methods of Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) are used to characterize the surface area using adsorption data below a relative pressure of 0.3, and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) equation was used to calculate the mesopore and macropore. Hg porosimetry was conducted on an Autopore IV 9510 series porosimeter. The pressure of Hg was increased up to 200 MPa, and mercury injection data were calculated for porosity (pore diameter >3 nm).

Methane sorption isotherms were determined by moisture equilibrated samples under reservoir temperatures. The Langmuir isotherm was used to model gas sorption capacity,

, where V is the volume of sorbed gas, VL is the Langmuir monolayer volume, P is the equilibrium pressure, and PL is the Langmuir pressure at which the sorption gas equals half of the Langmuir volume.

, where V is the volume of sorbed gas, VL is the Langmuir monolayer volume, P is the equilibrium pressure, and PL is the Langmuir pressure at which the sorption gas equals half of the Langmuir volume.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Mineralogy and lithofacies

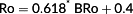

The Niutitang Formation shale primarily consists of clay minerals and quartz (Figure 2a); there are also minor plagioclase, potassium feldspar, calcite, dolomite, and pyrite. The content of clay minerals ranges from 12% to 46%, with an average of 32.2%. The clay minerals are primarily illite and an illite–smectite mixed-layer mineral, and generally, there is little kaolinite and chlorite (Figure 2b). The illite accounts for 26% to 91% of the clay, illite–smectite mixed layer minerals for 5% to 48%. The quartz accounts for 32–77% of the whole rock, with an average of 55.7%. The quartz particles are primarily silt to clay size and either layered or disseminated throughout the shale. The carbonate component is minor, comprising 1% to 21%, with an average of 2.4%. The carbonate is primarily present in the form of fracture fillings and cement. The pyrite accounts for 1–9%, with an average of 5%. The pyrite occurs mainly as framboidal pyrite, whose sizes are about 5–10 μm.

Four lithofacies can be identified in the Niutitang shale: siliceous shale, clayed mudstone, muddy siltstone, and siltstone (Figures 3 and 4).

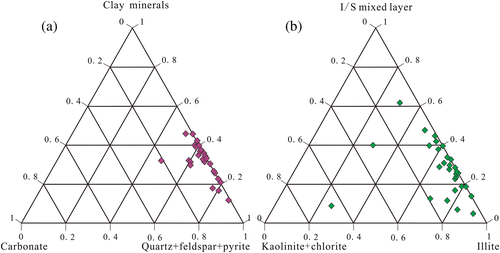

Siliceous shale is dark-coloured with high hardness (Figure 3a,b). This lithofacies has high quartz content, and the siliceous laminae is well developed. The quartz has unclear grain boundaries (Figure 4a). The lithofacies is rich in organic matter, which mainly occur as organic pellets (Figure 4b). This lithofacies is mainly developed in the lower Niutitang Formation (Figure 5).

Clay mudstone is laminated with dark colour (Figure 3c). Clay mineral is predominated with minor amount of quartz. The organic matter are mainly strips along the laminae (Figure 4c). In this lithofacies, pyrite is common and mainly pyrite framboidal showed in Figure 4d. This lithofacies is mainly developed in the middle-lower Niutitang Formation (Figure 5).

Muddy siltstone is laminated with greyish black colour (Figure 3d). The silt grains are mainly quartz with minor feldspar. The silt grains mostly have obvious grains morphology (Figure 4e).

Siltstone is grey coloured (Figure 3e,f). The silt grains are mainly quartz and tightly contacted with the grain size ranging from 40 to 100 μm (Figure 4f). The muddy siltstone and siltstone are mainly developed in the upper Niutitang Formation (Figure 5).

The organic-rich siliceous shale and clayed mudstone are characterized by fine grain size, scarce large debris, and compositions rich in pyrite and organic matter. These characteristics indicate that the two lithofacies were formed in a quiet water-body region with reducing water body. Here, the organic-rich laminated siliceous shale and clayed mudstone are interpreted as mainly deposited in the deep-water outer shelf, which is mainly developed in the lower Niutitang Formation (Figure 5). Grey mudstone and muddy siltstone are characterized by low TOC content, large debris increasing, and massive bedding. These characteristics suggest the decreased water depth and increased water power compared with black siliceous shale and clayed mudstone, which are mainly deposited in the inner muddy shelf. And the siltstone here interpreted as mainly deposited in the inner sandy shelf.

4.2 Source rock characteristics

The analysis of the source rocks indicated that the organic matter of the Niutitang shale is predominantly type-I kerogen and minor type-II kerogen. The residual organic matter in the Niutitang shale is present primarily as dispersed organic matter, as showed in Figure 6c,d. In the studied section, the TOC content ranges from 1.35% to 14.3%, with an average of 4.46% (Table 1). The Ro of the Niutitang shale ranges from 1.86% to 4.18%, with an average of 2.79%. In this study, the vitrinite reflectance values were calculated using the empirical formula

; the BRo here indicates the bitumen reflectance.

; the BRo here indicates the bitumen reflectance.

| Sample number | Lithofacies | TOC (wt%) | Ro (%) | Mineral content (wt%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay | Quartz | K-feldspar | Plagioclase | Calcite | Pyrite | Kaolinite | Chlorite | Illite | I/S mixed layer | ||||

| Bajiaozhai | MS | 1.63 | - | 37 | 60 | 2 | / | 1 | / | 65 | / | 26 | 9 |

| Kelou | CM | 3.37 | 3.42 | 38 | 54 | / | 8 | / | / | 1 | / | 54 | 45 |

| Linchaogou | CM | 4.03 | 2.89 | 34 | 60 | / | 6 | / | / | 2 | / | 56 | 42 |

| Dewang | CM | 8.85 | 4.18 | 27 | 57 | / | 7 | / | 9 | 4 | / | 91 | 5 |

| Yuhua | MS | 4.67 | 2.25 | 33 | 53 | 2 | 12 | / | / | 1 | / | 65 | 34 |

| Songlin | MS | 1.68 | 2.62 | 12 | 77 | 4 | 6 | 1 | / | / | 19 | 68 | 13 |

| Mahao | CM | 9.46 | 2.33 | 30 | 43 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 59 | 38 |

| Jianggu | SS | 6.39 | 2.67 | 18 | 71 | 4 | 2 | 5 | / | 10 | / | 83 | 7 |

| Bangdong | CM | 3.48 | 3.11 | 40 | 54 | 2 | / | / | 4 | / | 2 | 79 | 19 |

| Xiamafang | CM | 6.37 | 3.18 | 32 | 32 | / | 9 | 21 | 6 | / | 12 | 76 | 12 |

| Qingxi | MS | 1.66 | 2.62 | 21 | 57 | 2 | 11 | / | 9 | / | 3 | 74 | 23 |

| Morong | SS | 14.30 | 2.87 | 23 | 71 | / | 6 | / | / | 7 | / | 64 | 29 |

| Shiliang | MS | 1.51 | 2.64 | 36 | 52 | / | 12 | / | / | / | / | 81 | 19 |

| Majiang | CM | 7.93 | 2.80 | 32 | 59 | 2 | 2 | / | / | / | / | 60 | 40 |

| Yankong | CM | 2.5 | 2.47 | 46 | 50 | 1 | 3 | / | / | 4 | 4 | 30 | 62 |

| Qijiang | CM | 6.25 | 3.22 | 45 | 50 | / | 4 | / | / | 1 | / | 73 | 26 |

| Wengjiao | MS | 1.35 | 2.50 | 26 | 58 | / | 16 | / | / | 4 | / | 48 | 48 |

| Yuqing | CM | 8.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Meiziwan | CM | 4.85 | 2.25 | 30 | 67 | / | 1 | / | / | 28 | 3 | 29 | 40 |

| Yonghe (1) | MS | 1.85 | 2.59 | 42 | 53 | 1 | 3 | / | / | / | / | 71 | 29 |

| Yonghe (2) | MS | 2.16 | 2.68 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yonghe (3) | CM | 2.33 | 2.75 | 46 | 42 | 2 | 7 | 3 | / | 4 | / | 65 | 31 |

| Yonghe (4) | CM | 2.39 | 2.60 | 40 | 48 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | / | / | 73 | 27 |

| Yonghe (5) | MS | 2.40 | 2.58 | 30 | 37 | 4 | 15 | 8 | / | / | / | 74 | 26 |

| Yonghe (6) | CM | 2.37 | 3.07 | 35 | 49 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 | / | 68 | 30 |

| Yonghe (7) | MS | 2.38 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yonghe (8) | CM | 3.05 | 2.75 | 28 | 48 | 7 | 9 | 3 | / | / | 86 | 14 | |

| Yonghe (9) | MS | 2.47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yonghe (10) | CM | 4.32 | 3.04 | 33 | 63 | 2 | / | 2 | / | 6 | / | 77 | 17 |

| Yonghe (11) | CM | 5.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yonghe (12) | CM | 4.15 | 2.95 | 30 | 61 | 2 | / | 2 | / | 3 | / | 69 | 28 |

| Yonghe (13) | CM | 5.01 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yonghe (14) | CM | 4.55 | 2.89 | 39 | 55 | 2 | 2 | 2 | / | 2 | / | 74 | 24 |

| Yonghe (15) | CM | 4.23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yonghe (16) | SS | 5.80 | 3.27 | 17 | 72 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | / | / | 67 | 33 |

| Yonghe (17) | SS | 6.92 | 1.86 | 33 | 63 | 2 | / | 2 | / | 6 | / | 54 | 40 |

- Note. MS = muddy siltstone; CM = clay mudstone; SS = siliceous shale; - = not detected; / = zero value.

4.3 Pore space

4.3.1 Micropores

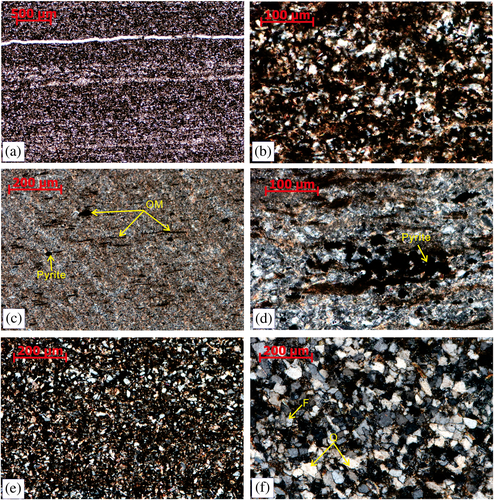

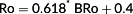

The micropores mainly occur in the minerals, pyrite framboids, and quartz grains, with the pore size ranging from 2 to 20 μm. The X-ray diffraction shows that clay minerals of the Niutitang shale are predominantly composed of illite and mixed layer I/S (Figure 2b), indicating that illitization clearly occurred. The micropores up to tens of micrometres in diameter can be observed in the clay minerals (Figure 6a–c). In addition, the intracrystalline pores are well developed in the pyrite framboids. These micropores are sufficient for gas molecules storage and seepage.

4.3.2 Organic pores

The organic pores mostly exist as densely beaded or honeycomb within the organic matter, with single organic pores nearly being round or oval. Organic pores are mainly nanoscale pores, with pore size ranging from 50 nm to 1 μm, and a small amount up to 5 μm (Figure 6d,e). The organic particles (size up to 10–200 μm) have complex internal structures, and the organic pores occur in the particles and are well connected. These pores are well developed in the shale, particularly those rich in organic matters (Figure 6e).

4.3.3 Microfractures

The SEM observation shows that the microfractures are widely developed in the Niutitang shale, mainly along the edges of the grains, here mainly quartz grains (Ding, Zhu, Cai, Gong, & Chen, 2013). Generally, these fractures extend about 5–50 μm, with the fractures opening about 1–5 μm (Figure 6f). The mineral grains are mostly distributed as scattered individuals in the shale; thus, these microfractures along the quartz grains not only increase the porosity and permeability of the shale but also are conducive to the shale reservoir reconstruction fracturing. The formation of the microfractures related to the differences between the mechanical properties of quartz grains and clay minerals.

4.4 Reservoir properties

In the study area, the Lower Niutitang Formation shale porosities range from 1.3% to 9.4%, with an average of 4.86%, that is, medium porosity. The permeability is very low, ranging from 0.0022 × 10−3 μm2 to 0.0125 × 10−3 μm2, with an average of 0.0075 × 10−3 μm2 (Table 2).

| Sample number | Lithofacies | Porosity (%) | Permeability (10−2 μm2) | BET SS (m2/g) | BJH CSS (m2/g) | BJH TPV (10−2 ml/g) | ARP (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelou | CM | 5.2 | 0.0059 | 10.50 | 9.37 | 0.0124 | 4.5 |

| Linchaogou | CM | 4.5 | 0.0022 | 15.30 | 26.95 | 0.0171 | 3.2 |

| Dewang | CM | 6.8 | 0.0075 | 3.88 | 4.45 | 0.0070 | 7.0 |

| Songlin | MS | 1.7 | 0.0037 | 0.74 | 1.21 | 0.0029 | 14.6 |

| Mahao | CM | 5.3 | 0.0052 | 5.58 | 8.09 | 0.0104 | 6.7 |

| Jianggu | SS | 6.7 | 0.0068 | 2.05 | 3.33 | 0.0040 | 6.7 |

| Qingxi | MS | 1.4 | 0.0047 | 6.97 | 8.43 | 0.0157 | 8.8 |

| Yuqing | SS | 12.9 | 0.0138 | 13.42 | 12.95 | 0.0173 | 5.4 |

| Majiang | CM | 7.5 | 0.0080 | 10.58 | 10.30 | 0.0092 | 3.7 |

| Wengjiao | MS | 1.3 | 0.0058 | 9.75 | 16.6 | 0.0129 | 4.2 |

| Yonghe (1) | MS | 2.6 | 0.0035 | 7.73 | 8.30 | 0.0111 | 5.7 |

| Yonghe (4) | CM | 3.7 | 0.0037 | 4.31 | 2.32 | 0.0038 | 7.8 |

| Yonghe (5) | MS | 4.3 | 0.0028 | 6.80 | 4.95 | 0.0171 | 3.2 |

| Yonghe (6) | CM | 4.2 | 0.0075 | 3.88 | 4.45 | 0.0070 | 7.0 |

| Yonghe (10) | CM | 2.8 | 0.0067 | 23.82 | 24.36 | 0.0221 | 3.8 |

| Yonghe (12) | CM | 4.8 | 0.0045 | 3.86 | 5.22 | 0.0074 | 7.2 |

| Yonghe (14) | CM | 6.2 | 0.0056 | 8.71 | 10.75 | 0.0089 | 3.7 |

| Yonghe (16) | SS | 9.4 | 0.0045 | 4.63 | 6.56 | 0.0092 | 7.1 |

| Yonghe (17) | SS | 6.8 | 0.0125 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.0029 | 17.0 |

| Average | 4.5 | 0.0063 | 7.9 | 9.48 | 0.013 | 7.57 | |

- Note. BET SS = BET specific surface; BJH CSS = BJH cumulative specific surface; BJH TPV = BJH total pore volume; ARP = medium radius of pores; CM = clay mudstone; MS = muddy siltstone; SS = siliceous shale.

4.4.1 Pore volume

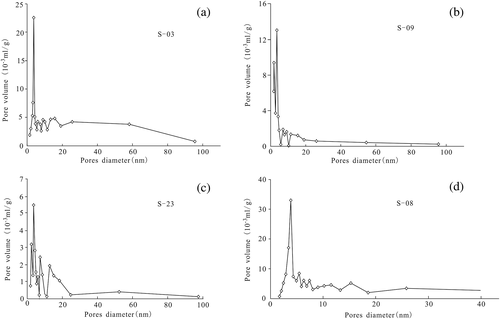

The micropore volumes of the Niutitang shale range from 2.79 × 10−5 ml/g to 1.85 × 10−3 ml/g, with an average of 6.39 × 10−4 ml/g (Table 2). The volume of the medium pores ranges from 8.99 × 10−4 ml/g to 5.29 × 10−2 ml/g, with an average of 1.05 × 10−2 ml/g. The total pore volume ranges from 2.6 × 10−3 ml/g to 5.24 × 10−2 ml/g, with an average of 1.19 × 10−2 ml/g. Table 2 shows that the specific surface area of the Niutitang shale in the study area ranges widely from 0.667 to 23.82 m2/g, with an average of 7.9 m2/g (Table 2). The pore diameters range from 3.2 to 14.6 nm, averaging 7.57 nm, and the median radius is between 1.6 and 8.5 nm, averaging 3.81 nm. The percentages of micropores (<2 nm), medium pores (2–50 nm), and macropores (>50 nm) are 6.45%, 85.23%, and 8.32%, respectively, suggesting that medium pores are dominant in the Niutitang shale.

4.4.2 Pore size distribution

The major pore size is expressed as a single peak, but there are also small additional modes (Figure 7), showing that most of the pore diameters are between 2 and 5 nm and range from less than 5 up to 100 nm in diameter. The mean coefficient is 0.45, showing that the pore throat size is centrally distributed. The displacement pressure is approximately 10 Mpa, and the mercury withdrawal efficiency changes greatly from 19.15% to 74.69%, with an average of 44.46%, suggesting that the pore throat widths are low.

4.4.3 Shale gas content

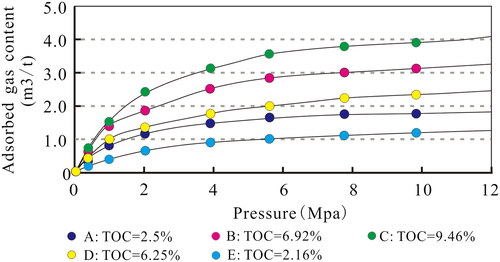

Nitrogen adsorption experiments suggest that the maximum adsorption gas content of the Niutitang shale is closely related to the TOC content and has a positive relationship with the TOC content (Figure 8). The maximum adsorption gas content of samples can reach 1 m3/t at 0.5 MP, greater than 2 m3/t at 2 MP~, reach 3.5 m3/t at 5 MP pressure. These data show the relative high gas content of the Niutitang shale.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Shale porosity and gas sorption capacity

Most of the pore diameters are less than 20 nm, mainly concentrate at about 10 nm (Figure 7), which is consistent with that the organic pores act as the main storage space. According to the pore-size classification proposed by Rouquerol, Avnir, Everett, Fairbridge, & Haynes (1994), the pores in the Niutitang shale are mainly mesopores, which is consistent with that the organic pores act as the key reservoir space in the study shale. Moreover, Figure 9a shows a strong relationship between the micropore volume and the TOC, suggesting that organic pores are dominant in the shale, and the porosity is controlled by the TOC content to a certain extent.

The porosity is also related to the mineral compositions and lithifacies (Loucks, Reed, Ruppel, & Jarvie, 2009; Ross & Bustin, 2009). Fractures along laminae are abundant in the layered shale, where this type of fracturing is significant in the laminated shale and silty shale. The siliceous shale is rich in organic matters, and thus, organic pores are well developed in this rock type. The fractures are not widely developed in the clayed mudstone, whereas pores in organic matter are. Pyrite is abundant in the clayed mudstone, forming a large number of intracrystalline pores in the pyrite framboidals. The studies suggest that the lithofacies has different porosity, permeability, pore volume, and pore size (Table 3). In the study area, the main lithofacies are siliceous shale and laminated clayed mudstone in the lower Niutitang shale, and thus, the microfractures and organic pores comprise the primary reservoir space. In general, the porosity and permeability of the lower Niutitang shale is better than that of the middle and upper interval (Figure 5). What's more, the increases in the amounts of quartz and feldspar grains increase the brittleness of the rock, which leads to generation of additional fractures (Ferrill et al., 2014; Gale, Laubach, Olson, Eichhubl, & Fall, 2014). The porosity correlates in linear fashion with the amount of these minerals, including quartz, feldspar, and carbonate (Aplin & Macquaker, 2011; Bernard et al., 2012).

| Sedimentary facies | Lithofacies | TOC (%) | Porosity (%) | Permeability (10−2 μm2) | Pore volume (ml/g) | ARP (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer shelf | Siliceous shale | 5.8–14.73 (9.2) | 6.7–12.9 (8.95) | 0.0094 | 0.012 | 9.05 |

| Clay mudstone | 2.33–9.46 (4.96) | 2.8–7.2 (5.1) | 0.0057 | 0.0097 | 5.46 | |

| Inner shelf | Muddy siltstone | 1.35–4.67 (2.21) | 1.3–4.3 (2.3) | 0.0041 | 0.01 | 7.3 |

- Note. TOC = total organic carbon.

Organic matter has a strong adsorption of gas, where there is increased shale gas adsorption and adherence on the surface of kerogen in the shale (Curtis, Cardott, Sondergeld, & Rai, 2012; Lu, Ruppel, & Rowe, 2014; Mastalerz, He, Melnichenko, & Rupp, 2012). The adsorbed gas within the shale is greatly affected by the TOC, and there is a positive correlation between these two parameters (Figure 9b).

5.2 Sedimentary environment and lithofacies act as the key control factors for shale reservoir characteristics

The organic-rich laminated siliceous shale and clayed mudstone are mainly deposited in the deep-water outer shelf, which is mainly developed in the lower Niutitang Formation (Figure 5). Grey mudstone and muddy siltstone are mainly deposited in the inner muddy shelf. And the siltstone here interpreted as mainly deposited in the inner sandy shelf. As mentioned above, the sedimentary facies control the lithofacies development and distribution; furthermore, the lithofacies control the TOC content, pores development, and porosity (Liang et al., 2012). Table 3 shows that the siliceous shale has high TOC content (average being 9.2%), high porosity (average being 8.95%), and ARP (9.05 nm). And the siliceous has high quartz content (up to 77%), suggesting that it has high brittleness (Table 1).

5.3 Factors favouring the accumulation of shale gas

5.3.1 Effective thickness and extent of black shale

A substantial thickness of the black shale is a precondition for commercial accumulations of shale gas. The U.S. exploration experience demonstrates that a minimum thickness of 30 m of black shale is required for successful shale gas exploration (Chalmers et al., 2012; Zou et al., 2010), once other requirements, including the TOC, Ro, and fragile mineral content, are met. The Niutitang Formation shale is widespread and has considerable thickness, which is approximately up to 200 m, the thickness of organic-rich black shale is up to 50 m (Figure 1a). The Niutitang shale therefore has the prerequisites for shale gas enrichment and good prospects for widespread shale gas exploration.

5.3.2 Favourable organic carbon content and organic matter maturity

The abundance of organic matter is fundamental for oil and gas generation and accumulation (Bowker, 2007; Liang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2008). Studies showed that the TOC content and the content of convertible organic carbon control the organic pores abundance (Jarvie et al., 2007). Figure 9 suggests that the TOC content has a positive correlation with the adsorbed shale gas and pore volume. In addition, the nitrogen adsorption experiments suggest that TOC content controls the maximum adsorption gas content, as showed in Figure 8. The Niutitang interval is an excellent source rock, with TOC amounts ranging from 0.4% to 16.3% (average of 4.43%). This high TOC content indicates the high hydrocarbon potential and strong adsorption capacity of the shale gas (Nelson, 2009). The Lower Cambrian shale evolved into the dry gas and thermogenic gas window, with organic matter being overmature (Ro > 2%) in Niutitang shale. The Ro values suggest a mature to overmature stage. The source rocks generate gas primarily at this maturity stage, which provides conditions favourable for shale gas enrichment.

5.3.3 Favourable sedimentary environment

The Niutitang shale in the study area was deposited in a shelf environment, specifically a deep-water shelf (Liang, Guo, Bian, Chen, & Zhao, 2009; Yan et al., 2016; Zhou, Kang, Wang, Peng, & Xiao, 2017). Early in the deposition of the Niutitang Formation, relative sea level was high, and a large set of fine-grained sediments were deposited, primarily black siliceous shale and clayed mudstone. This interval acts as the key target for shale gas exploration and is mainly deposited in the deep-water shelf reducing environment. Liu, Feng, Shen, Khan, and Planavsky (2018) suggested that the increased productivity as a primary driver of marine anoxia in the Niutitang Formation based on the analysis of TOC content, Ba enrichments, and trace metal enrichments. The anoxic water environment will be helpful for the preservation of organic matters (Jin et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2018). What's more, the deep-water shelf facies is widely developed in the Early Cambrian Period in Sichuan Basin, which means a large shale gas exploration area in the basin.

The sedimentary environment provided conditions for preservation of organic matter (Liu et al., 2016); what's more, the widespread black shale distributed in the stable environment. Based on a comprehensive evaluation of the factors discussed above, the south-east part of the study area is most favourable for shale gas exploration. First, there is sufficiently thick shale for industrial exploration for and exploitation of shale gas. Second, there are sufficiently high levels of TOC and appropriate maturity ranges, which are necessary conditions for the presence of sufficient amounts of absorbed gas in the shale. Finally, the widespread distribution of potential target sedimentary facies is another important factor favouring shale gas exploration prospects in this area and its regional expansion.

Currently, China has performed shale gas exploration in various shales (Yang, Liang, Zhang, ZaixingJiang, & Tang, 2015) and has a breakthrough in the Longmaxi shale and Niutitang shale in Sichuan Basin (Liang et al., 2017). By the end of Year 2017, shale gas production has been up to 10 billion cubic in the Longmaxi shale. Compared to the Longmaxi shale, the Niutitang shale is characterized by higher thermal maturity (Ro up to 4%), favourable burial depth, TOC content, and porosity, although smaller than that of Longmaxi shale (Liang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2015). Compared with major gas shale in the United States, the Niutitang shale has relative low present TOC content, because of the high thermal maturity as mentioned above. The porosity of U.S. gas shale is relative high (up to 14%), which is much higher than that of the Niutitang shale (Abouelresh & Slatt, 2012; Loucks et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014, 2017). The thickness of the organic-rich black shale is more than 50 m, which is not inferior to that of Longmaxi shale and these gas shales in the United States (Curtis, Sondergeld, Ambrose, & Rai, 2012; Yang et al., 2015).

6 CONCLUSIONS

The Niutitang Formation shale is an interval important for shale gas exploration in southern China. The minerals of the Niutitang shale consist primarily of quartz, clay minerals, carbonate, and pyrite. The TOC content ranges from 1.35% to 14.3%, with an average of 4.46%. The Ro of the Niutitang shale ranges from 1.86% to 4.18%, with an average of 2.79%. Organic pores, microfractures in the clay mineral crystals and along the boundaries of quartz grains, and micropores in the clay minerals and the pyrite framboids were identified, and these features provide pore space for the shale gas. The organic pores may constitute the primary storage space for the shale gas. Most of the pore diameters are less than 20 nm, mainly concentrate at about 10 nm, which is consistent with that the organic pores act as the main storage space. The pore volume and gas content are strongly controlled by the mineral composition and lithofacies, and TOC content. The conditions favourable for accumulation of shale gas in the study area include (1) an effective thickness and widespread distribution of the Niutitang shale, (2) a high TOC content and appropriate maturity interval, and (3) a favourable sedimentary environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research presented in this paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1762217 and 41602142), the Natural Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2016DB16), the Opening Fund of Shandong Province Key Laboratory of Depositional Mineralization & Sedimentary Mineral (DMSM2017064), and the National Science and Technology Special Grant (2016ZX05006-003 and 2016ZX05006-007).