From clicks to crisis: A systematic review of stressors faced by higher education students studying online

Abstract

It is well established that most higher education students experience stress, stemming from a range of factors such as exams, time demands, and financial pressure. Given the rising number of students completing their tertiary studies online, identifying stressors faced by the growing online student cohort is important. Therefore, a systematic review was undertaken to identify and consolidate what the key stressors experienced by online higher education students are. This review analyzed 68 articles published in English between 2001 and 2022, retrieved from three databases: ERIC, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. The review found that online university experience a range of stressors, including challenges related to course delivery, technology access, online communication, home learning environments, peer relationships, motivation, and assessments. Strategies to mitigate these stressors include improving course design with engaging and interactive contents, providing technological support and digital literacy training, fostering peer connections through structured interactions, and offering flexible assessments tailored to online contexts. These findings underscore the importance of considering the unique stressors experienced by online students and highlight the need to develop interventions to mitigate these stressors when designing and delivering online courses.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is now well-established that higher education is a stressful environment for students, with studies finding that most students experience stress in some capacity during their education (Robotham & Julian, 2006). Stress is unavoidable (Rana et al., 2019) and not always negative given that stress is required for motivation and enables students to respond effectively in particular circumstances (Schafer, 1996). However, stress can also lead to adverse outcomes, including lower academic successes, student attrition (Pascoe et al., 2020), and students experiencing mental health challenges. Regarding the latter, Saleh et al. (2017) found that most higher education students reported living with psychological distress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. These mental health experiences also place greater demand on university mental health services (Thorley, 2017). Therefore, understanding the sources of stress is an important step in reducing the stress experienced by students. This is especially true given the increasing emphasis on higher education student well-being, and the current lack of research and interventions within this space (Upsher et al., 2022).

Sources of stress, or ‘stressors’, are defined as any event, stimulus, or circumstances that can disturb an individual's daily functioning (Bernstein et al., 2008). These stressors can be intrinsic or extrinsic and are individualistic, in that what could be a stressor for one student may not be a stressor for another (Rana et al., 2019). Robotham and Julian (2006) reviewed stress in higher education literature and found common stressors include examinations, time demands, financial pressures, and parental pressure. Another study found common stressors for high school and tertiary students were related to the pressure of academic success (Pascoe et al., 2020). Recent research has also found that the COVID-19 pandemic has, and will likely continue to exacerbate, the stress experienced by university students (Prasath et al., 2021). Although this research provides a useful foundation of typical stressors in higher education, there is limited research investigating whether these factors are consistent with, or relevant to, online university students. Online education differs from on-campus education in that barriers such as class times, travel, and in-person examinations are alleviated, whereas other challenges may be present in adapting to technology, increased work demands outside of university, or duration since prior study experience.

Online higher education course enrollments have been increasing significantly, with the percentage of students from the United States studying one or more undergraduate course online increasing from 15.6% in 2004 to 43.1% in 2016 (Snyder et al., 2019). This trend was intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic which led to a rapid increase in courses being offered 100% online (Sun et al., 2020). Given this increase in online education and its potential for unique stressors, it is essential to identify the common stressors experienced by students studying online. An understanding of these stressors provides a foundation for supporting the well-being and academic success of the growing online student cohort. Given this, a systematic review is the most appropriate methodology due to the lack of clear direction and limited research in this space.

Specifically, the objective of this review is to identify the common stressors experienced by higher education students studying online.

2 METHOD

This systematic review was conducted according to the procedure outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009).

2.1 Search strategy

Systematic searches were performed in June 2022 in three databases: ERIC, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. The search terms were developed by two authors (authors one and four) in conjunction with academic librarians based on prior evidence. The following key words were searched individually and in various combinations: “student attitudes”, “exp college students”, “postgraduate student”, “graduate students”, “fear”, “mathematics anxiety”, “anxiety”, “test anxiety”, “social anxiety”, “speech anxiety”, “academic stress”, “computer anxiety”, “student or learner”, “stress*”, “anxiet*”, “worry*”, “worrie*”, “concern*”, “anxious*”, “fear?”, “distress*”, “apprehens*”, “televised instruction”, “virtual classrooms”, “distance education”, “electronic learning”, “online or electronic or web or internet or remote or virtual* or distance”, “learn* or educat* or study* or college* or instruction or course? or program? or programme?”, “exp higher education”, “exp college students”, “postgraduate students”, “graduate students”, “exp colleges”, “exp education degrees”, “college? or uiversit* or undergrad* or postgrad* or masters or bachelor* or higher ed or tertiary ed or post-secondary or post secondary or grad* school or adult education or further education or advanced education or higher learning”, “open university*”, and “virtual universit*”.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

The aim of this review was to identify and consolidate what the key stressors experienced by online higher education students are. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (a) the study was published in English, (b) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal, (c) the study was published between the years 2000 and 2022, (d) the study presented the original data, with dissertations, books, and reviews excluded from the current review, and (d) the study measured the experience of higher education students in a completely online environment. Studies were excluded if they measured the experience of students outside of tertiary education (e.g., high school), students in hybrid courses (e.g., partially online and partially in-classroom), measured learning outcomes (e.g., final course grade) rather than experience outcomes (e.g., stress), studies using historical methods no longer in common use in 2022 (e.g., deliver courses via CD-ROM), validation of new measures, retention rather than student experience, and courses that transitioned some components online due to COVID-19 restrictions (e.g., online access to lecture content during an interim period). We excluded studies that assessed courses that transitioned online during the COVID-19 pandemic as these courses often did not reflect a purposeful and systematic design and development to enable online learners. Rather, these courses often reflect emergency remote teaching which is distinct from purposely designed online education and therefore does not provide an appropriate assessment for generalization. Emergency remote teaching involves a temporary transition to a novel, quick to set up, delivery format that can be implemented to manage a crisis which prevents the use of the traditional delivery format in which the course was designed (Hodges et al., 2020).

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

Two academic librarians completed the searches in each database. Author two then screened the titles and abstracts of each study to determine eligibility. Full texts of the studies deemed eligible were then screened for inclusion by author two and an independent researcher to assess reliability. The two researchers achieved an inter-rater reliability of 98%, with the two researchers meeting to discuss and resolve the discrepancies. Finally, the reference lists of the included papers were assessed by author two for further relevant articles; however, this did not result in any additional articles being included in the current review. The searches resulted in 1997 potential sources for review. The references were exported to covidence systematic review software for screening. Covidence is a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews (Covidence, 2022). Of the initial 1997 articles, 279 were removed as duplicates and 1718 were screened by titles and abstracts which led to a further 1444 records being excluded. The full texts of the remaining 274 articles were reviewed, with 206 removed due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in a final set of 68 articles to be reviewed in the present study (see Figure 1).

PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the study selection criteria.

Research documenting people's experiences, opinions, and perspectives (‘views’ studies) often uses nonexperimental or qualitative research designs. Hence, reviews of such studies must use adaptive methods like that of qualitative analysis (Harden et al., 2004). The current study was guided by Harden et al.’s (2004) framework for synthesis of nonexperimental views research. Author two first performed data extraction using the following categories: study design, sample size, sample gender distribution, sample age, sample study discipline, student stressors identified, and strategies provided to mitigate student stressors. We used the definition of a ‘stressor’ being any event, stimulus, or circumstance that is a source of stress (Bernstein et al., 2008), to guide our extraction, meaning that any source of stress in the online learning context was considered a stressor. As the comparison of effect sizes is not applicable to qualitative data, findings of the review studies were aggregated to allow for the development of codes, and subsequently themes and subthemes, relevant to the research aims.

3 RESULTS

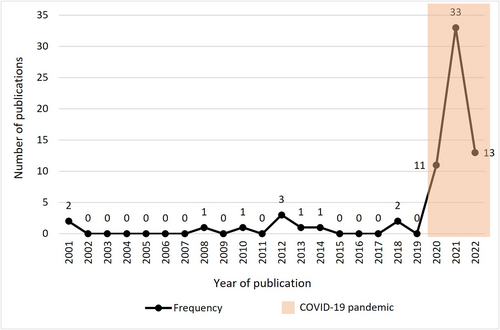

The review demonstrates a considerable increase in publications on students' experience studying online following the global spread of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) at the end of 2019. The number of included papers peaked in 2021 with 33 publications, approximately three times that of the 2 decades prior to COVID-19 (Figure 2). The recent increase in studies concerning COVID-related online learning provided a challenge for the authors in differentiating stressors that may be related to online learning in general or as a result of COVID-19 public health measures (e.g., social isolation and feelings of stress/worry). As such, although the focus of this review is on identifying the common stressors experienced by online students, the interpretation of results should consider the cumulative effects of COVID-19 on participants who did not voluntarily enroll in online learning.

Publication timeline of included papers (n = 68).

3.1 Study characteristics

All included studies were published in English between 2001 and 2022. Most studies used either a qualitative (n = 28) or mixed methods (n = 28) design to describe the stressors associated with online study. The majority of included publications used samples from the United States of America (n = 15), Turkiye (n = 7), and Jordan (n = 5); however, 33 countries are represented in the total sample. Please see the supplementary information for a complete list of articles included in the review and the demographics of these.

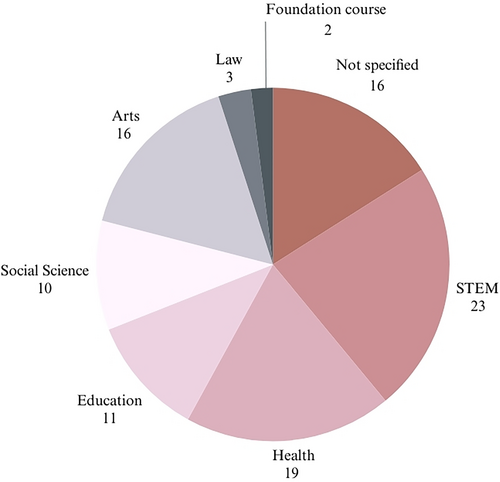

Samples covered a range of study disciplines, including STEM (34%), health (28%), arts (24%), education (16%), and social sciences (15%; Figure 3). More than two-thirds of included studies (n = 46) did not disclose participants' age; of those that did (n = 22), 12 had samples with an age range or mean age above 30. Of the studies that provided gender data (n = 42), 54.4% were female (45.2% male, 0.4% other/prefer not to say). See supplementary materials for a tabulated summary of individual study characteristics. Note that accepted studies may include multiple demographic groups (e.g., staff and students); however, this review focuses on the experiences of student participants only.

Frequency of sample study discipline (n = number of papers).

3.2 Potential for bias

Consideration should be given to potential biases within the accepted studies. Reviews of qualitative, ‘views’-based research can face challenges due to the nonstandardized approach to these studies (Harden et al., 2004). There is substantial variation in sample size between accepted studies, from two participants (Li & Zhang, 2021) to over six thousand participants (Yaghi, 2022). Critically, many studies did not disclose potentially important demographic information, such as participant age, gender, or study discipline. The sample of accepted papers presents predominantly qualitative data, which may lack the objective reliability and validity measures commonplace in randomized trials (Harden et al., 2004). There is a probable Western bias within the data, with 27% of included studies (n = 18) based on participant data from North America. In addition to this, there is a lack of research focusing on South American and African samples; some studies based in Africa were excluded due to the sample or course delivery method not meeting the inclusion criteria (e.g., Kwaah & Essilfie, 2017; Osei, 2010; Yeboah & Nyagorme, 2022).

Notably, 84% of accepted papers (n = 57) were published following the spread of COVID-19. Although the subsequent global transition to distance education provides important insights into student experiences of online learning, these data may not reflect general online student sentiment. Attitudes likely differ between students who elected to enroll in online learning and those who were required to do so due to extraneous circumstances. Negative sentiments surrounding online learning may also be compounded by the impacts of COVID-19 prevention measures, particularly concerning feelings of stress and social isolation (Loades et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2021).

3.3 Common stressors for online students

Table 1 presents stressors reported by university students enrolled in online studies and the strategies proposed in the literature to mitigate these stressors. Stressors are reported at an overall theme level and where appropriate at a specific stressor level. The table lists the stressor theme from most commonly reported in the literature to the least. A reference list of the literature that reported each stressor and strategy is provided in supplementary materials.

| Theme of stressors | Specific stressors | Proposed strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Course delivery |

|

|

| Internet & technology |

|

|

| Online communication |

|

|

| Learning in the home |

|

|

| Peer relationships |

|

|

| Motivation and engagement |

|

|

| Assessments |

|

|

| Staff |

|

|

| Physical challenges |

|

|

| Language/Culture |

|

|

| Work–life balance |

|

|

| On-campus life |

|

|

| Finances |

|

|

3.4 Course delivery

A common theme of stressors pertained to issues regarding course delivery, with 53 studies reporting these stressors. Specific stressors related to how students believed that they do not absorb or retain as much information in online courses as they do in on-campus equivalents (e.g., Al-Nofaie, 2020; Al-Salman et al., 2022; Barr & Johnson, 2021) that there were delayed and limited responses from staff (e.g., Koh & Wong, 2021), too much content (e.g., Masha'al et al., 2020; Murphy & Mahoney, 2001; Sowan & Jenkins, 2013), as well as that the online course/content was not engaging. Many studies provided strategies for how to minimize stressors created by course delivery. These included using the asynchronous model to allow for flexibility, although other papers also suggested having live/synchronous aspects either as compulsory aspects of the course (e.g., Durak & Çankaya, 2020; Kala et al., 2021) or to complement the asynchronous aspects. Other common strategies included ensuring the online content was high quality, varied, and interactive and providing instant feedback (Day et al., 2020) as well as regular communications from staff (e.g., a weekly newsletter; Dagman & Wärmefjord, 2022). The reviewed literature also recognized that institutions need to allocate resources and educators need time and support to learn online-appropriate methodologies for designing organized and engaging course content (Kelly, 2022).

3.5 Internet and technology

Another common theme related to stressors was associated with Internet connection and electronic devices (n = 52). Within this category, poor Internet connection was the most common complaint, while many studies also reported that students lacked access to the appropriate electronic device or equipment necessary to undertake online study. This was due to a range of factors, including financial barriers, outdated devices, and needing to share devices with family members. In addition, lacking technological literacy (e.g., Moawad, 2020) or being unfamiliar with the necessary software/programs was the third most frequent stressor within this theme. Given that this stressor was present in many studies, there were also many strategies suggested to minimize it. These mainly pertained to increasing access to Internet (e.g., through grants or infrastructure changes, Ashri et al., 2020; Demirbilek, 2023; Lambert & Dryer, 2017; Šorgo et al., 2022); however, it was also suggested that students should receive training and/or resources regarding how to use the technology and that offline materials should be provided to students (such as making downloaded content available; Giannoulas et al., 2021). Providing low-stakes opportunities to practice with technology was also recommended (Petillion & McNeil, 2020). Moreover, encouraging students to view technological literacy as a valuable life skill and incorporating it as a goal during course orientation can be helpful (Forde & Gallagher, 2020).

3.6 Online communication

Issues related to online communication were also common, with specific stressors identified including students finding communication online difficult, due to the lack of nonverbal cues (body language) in video conferencing, and inability for voice intonation in online chats or forums. Communicating in synchronous classes, typically via video conferencing software, did not feel natural (e.g., Sharma & Bumb, 2021); or was described as “embarrassing” (Dagman & Wärmefjord, 2022). The strategies provided to minimize these stressors were for educators to set clear expectations regarding online communication and “conversational norms” (Ledford et al., 2023), using “breakout” rooms on video software. Additionally, one author suggested using emoticons and various text-speak and online expressions like “LOL” to help overcome the lack of nonverbal cues and voice intonation and “bring life to the online classroom” (Martinak, 2012).

3.7 Learning in the home

Stressors associated with learning from inside the home environment were also common with the primary complaint referring to distractions within the home (e.g., Idris et al., 2021; Mohammed et al., 2021), such as background noise (e.g., Van et al., 2022) and family conflict. Inadequate workspaces and increased family responsibilities, such as housework and caring (e.g., Washburn, 2021), were additional stressors for online students within the home. Only one study provided a strategy to minimize these stressors, where Kristianto and Gandajaya (2023) said that educators should encourage their students to create study spaces conducive to learning.

3.8 Peer relationships

Many studies (n = 23) also found that a lack of peer contact was a stressor for online students, due to them feeling isolated (e.g., Morgan et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2010) and experiencing a loss of connection to others (e.g., Baltà-Salvador et al., 2021). Some strategies to minimize these stressors were implementing peer-to-peer interactions throughout the online courses (e.g., Miranda et al., 2022), implementing a mentor program, and building community bonds such as by creating opportunities for students to share personal interests like favorite songs (Ruiz-Alonso-Bartol et al., 2022).

3.9 Motivation and engagement

Twenty-two studies reported stressors associated with a decrease in motivation and engagement. Primarily, students commented on general feelings of low motivation (e.g., Moorberg et al., 2021; Topkaya et al., 2021) and engagement in their studies. Students also described difficulty managing their self-discipline when studying online as compared to on-campus. A lack of structure and routine—in both course delivery and students' study lives— was another common stressor. For example, students felt low motivation to study consistently when all course materials were readily available online, as opposed to the requisite attendance of scheduled classes to receive information. Two strategies to minimize these stressors were provided in the literature, firstly providing students with resources/activities to foster self-directed learning (e.g., Tuchler, 2021), such as taking a learner-centered approach to the course (Li & Zhang, 2021), and to provide or suggest a daily or weekly study schedule for students, including expected study hours and breaks to avoid burnout (Erickson et al., 2022).

3.10 Assessments

Stressors associated with course assessments were also common (e.g., Yeung & Yau, 2022), including students stating the methods of assessment were inappropriate for the online context (e.g., Zou et al., 2021), and concerns were raised about the fairness of evaluations in terms of how the university would prevent plagiarism and cheating in online assessments. Strategies suggested to minimize these concerns were that assessments should be developed in a way that is tailored to online learning, that there needs to be transparency over the assessment process, and that flexible deadlines should be implemented.

3.11 Other stressors reported

Other stressors that were reported in the studies, less frequently, were the staff themselves being a cause of stress, as they were perceived as disinterested (Ertürk Avunduk & Delikan, 2021; Durak & Çankaya, 2020) or generally low quality. Providing staff with training regarding how to effectively educate online was a common strategy provided in the literature. Stressors pertaining to physical challenges like eyestrain and back pain were also reported. Students also reported being stressed due to managing various responsibilities, not getting a ‘true’ university experience or due to financial challenges. One study did suggest that students should be educated regarding ergonomic practices (Yücelsin-Tas & Türkân, 2021) to reduce physical strain (e.g., Yüce, 2022), whereas another said that audio and visual tools should be used effectively to support English acquisition for students with English as a second language (Tan et al., 2010).

3.12 COVID-19 related stressors

Many papers included discussion of the direct impacts of COVID-19 on students who have transitioned to emergency remote learning, such as health concerns over contracting the virus, structural changes to the academic year, and the cancellation of important events like graduations. Although the consideration of these impacts is important, they largely represent extraordinary circumstances and thus do not reflect ‘common’ stressors for online university students. However, there are a number of stressors relevant to online higher education that warrant further discussion.

Online equivalents were viewed as insufficient replacements for practical classes that require a “hands-on” approach, such as for students in STEM and health (e.g., Ertürk Avunduk & Delikan, 2021; Pokryszko-Dragan et al., 2021). Students found it difficult completing some courses at home that would typically require the use of specialized laboratory equipment or other on-campus facilities. Students reported that the transition to online learning lacked standardization across subjects, as staff used varying online applications for course delivery and had different levels of experience with online teaching. Some students were unhappy with the quality of remote learning received as instructors lacked the requisite skills for online teaching and relied too strongly on asynchronous delivery.

Descriptions of students' reported mental health stressors, such as feelings of depression and anxiety, were not uncommon. Due to the proportion of included studies published during the COVID-19 pandemic, a relationship between online learning and experiences of depression and anxiety cannot be assumed, though it warrants further investigation.

4 DISCUSSION

The results of this review highlight the number of stressors faced by university students who are engaged in online learning. As online education continues to grow in popularity, understanding these challenges and identifying effective strategies to address them are essential for improving student outcomes and satisfaction. This systematic review examines studies published over the past 22 years, identifying key stressors associated with online learning and their implications for students, instructors, and institutions. Additionally, given that a significant proportion of studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, we consider how the unique circumstances of this period may have influenced these stressors.

4.1 Common stressors in online learning

A major stressor identified in this review was the method of course delivery. Students frequently reported issues such as disorganized course structures, unengaging content, and limited face-to-face interaction, as well as delayed responses from instructors, all of which contributed to increased stress. Students also perceived a lower retention of information in online courses compared to in-person learning. The preference for synchronous versus asynchronous learning formats is a contentious issue in the literature reviewed. Although some students valued the flexibility of asynchronous courses, they often underestimated the workload required for university-level studies (Baruth et al., 2021). Although some studies recommended asynchronous approaches to enhance flexibility (e.g., Almendingen et al., 2021; Baltà-Salvador et al., 2021; Gedera, 2014; Ghazi-Saidi et al., 2020), others emphasized the importance of synchronous interactions for engagement and learning outcomes (e.g., Durak & Çankaya, 2020; Dvoráková et al., 2021).

Technological barriers, including poor Internet connectivity (e.g., Hendricks, 2012) and inadequate access to necessary devices (e.g., Essex & Cagiltay, 2001), were also among the most frequently cited stressors. These challenges disproportionately affected students from lower-income backgrounds (Arıcı, 2020) or those residing in areas with limited technological infrastructure (Ruiz-Alonso-Bartol et al., 2022). Limited technological literacy further compounded these challenges. Online communication also caused stress for students as the absence of nonverbal cues in digital interactions hindered their ability to interpret tone and intent, making discussions feel unnatural or intimidating. Additionally, the home learning environment introduced stressors such as frequent distractions, lack of dedicated study spaces, and increased familial responsibilities (Ensmann et al., 2021). Unlike institutional settings, home environments often lack the structure necessary for focused academic work.

Peer relationships also suffered in the online learning context, with students frequently reporting feelings of isolation and disconnection (Kaufmann & Vallade, 2022). Motivation and engagement declined for many, influenced by self-discipline challenges, the absence of a structured routine, and the lack of in-person class interactions. Assessment-related concerns further contributed to student stress, with many expressing frustration over the fairness and appropriateness of online evaluations. Although online learning does offer flexibility, it requires a high degree of independent learning and self-regulation (Sim et al., 2020), which can be particularly challenging for students accustomed to face-to-face instructions (Iverson et al., 2005).

Beyond these primary concerns, additional stressors included perceived instructor disengagement, physical discomfort from prolonged screen use, and language barriers, particularly for students who are nonnative speakers. Addressing these challenges requires targeted interventions and strategic course designs to enhance the online learning experience.

4.2 The context of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant increase in online learning, with many students transitioning to digital education involuntarily. Although many of the stressors mentioned above are common to online learning in general, COVID-19 added additional layers of complexity. For example, due to the sudden transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, courses and coordinators were unprepared and unfamiliar with best practices for online learning. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns exacerbated these challenges by forcing students to learn from home quickly without adequate preparation. Moreover, more people being at home during lockdowns increased the potential for distractions and conflicts (Baltà-Salvador et al., 2021; James et al., 2021).

5 STRATEGIES TO MITIGATE ONLINE LEARNING STRESSORS

The reviewed literature suggests several strategies to address these challenges, which can be implemented at the student, instructor, and institutional level.

5.1 What can students do?

Students play a primary role in addressing stressors related to the home learning environment and physical challenges. They must establish dedicated study spaces and adopt ergonomic practices to support their well-being. Although these responsibilities ultimately fall on students, instructors can encourage such practices by providing guidance and relevant resources. For many online students, they also need to balance their studies with multiple responsibilities in a sustainable way, including work, family obligations, and parental duties (Samra et al., 2021).

5.2 What can instructors do?

-

Consider the design and delivery of the course

To develop engaging online courses, established strategies include shorter concept lectures, interactive activities, and clear, concise materials presented in a predictable format with an appropriate balance of text and imagery to minimize cognitive overload and enhance student engagement (Driggs & Brillante, 2020; Esson, 2016). A balanced combination of asynchronous and synchronous methods is recommended, as offering students opportunities to ask questions in real time and engage with their peers (Fallatah, 2020; Jung et al., 2012; Petillion & McNeil, 2020) can foster peer connections, addressing another stressor identified by students.

-

Consider technology challenges

While increasing access to technology and reliable Internet may be beyond the scope of an instructor's control, it is crucial for educators to recognize that technology-related issues are a common source of stress for students (Govender et al., 2021; Nikas et al., 2022). Instructors should also consider alternative solutions, such as providing downloadable materials for offline access (Giannoulas et al., 2021; Kelly, 2022; Yücelsin-Tas & Türkân, 2021). Additionally, promoting technological literacy as a fundamental skill through course orientation and training can help alleviate stressors related to unfamiliarity with digital tools (e.g., Berry, 2018; Dzakiria, 2008; Forde & Gallagher, 2020) and improve educational accessibility.

-

Consider online communication styles and set expectations

To enhance online communication, setting clear expectations (Ledford et al., 2023), utilizing breakout rooms for smaller discussions, and fostering a sense of community through informal online interactions are effective strategies. Incorporating visual elements such as emoticons (e.g., Dunlap et al., 2016) and text-based expressions can help replicate certain aspects of face-to-face communication. Clear guidelines for online participation (e.g., “share one thing you learned about…") and specific instructions on how students should contribute (e.g., “write one thing in the chat you learned…") are crucial for promoting clear and relevant discussions (Ledford et al., 2023).

-

Consider how to encourage students to be self-directed learners

For motivation and engagement, strategies such as learner-centered approaches, self-directed learning resources, and structured study schedules may help students maintain motivation. One strategy is to post weekly announcements in the online platform that serve as a reminder of specific topics, new materials uploaded, and changes in the schedule. Additionally, it was recommended to provide or suggest a daily or weekly study schedule for students, including expected study hours and breaks to avoid burnout (Erickson et al., 2022).

-

Consider how best to assess online students

To address assessment-related stressors, it is crucial to design assessments that are specifically tailored to online learning contexts, ensure transparency in grading policies, and incorporate flexible deadlines. Striking a balance between maintaining academic integrity and minimizing student stress is a challenge that institutions must carefully navigate. For instance, avoiding the use of proctored software for exams, which require stable Internet access and a suitable device at a specific time, can help reduce stress (Fallatah, 2020). Interactive oral assessments have been identified as a best practice for preventing plagiarism in online assessments, according to the literature reviewed (Khan et al., 2021)

5.3 What can institutions do?

Given the importance of ensuring access to reliable Internet and suitable equipment, institutions can improve support for students with limited Internet connectivity or insufficient access to technological devices by offering loan devices upon enrollment, as recommended by Gamage et al. (2020). Collaboration with other stakeholders, such as university administration and technology companies, can also help facilitate students' access to appropriate devices and Internet connectivity (Agormedah et al., 2020).

Additionally, creating content compatible with mobile applications should be considered, as many students rely on mobile devices when Internet connectivity is unavailable or unstable (Oyedotun, 2020). Offering workshops on time management and organizational skills (Erickson et al., 2022) as well as providing counseling services for students dealing with personal challenges (Al-Salman & Haider, 2021) can further support student success.

Educational institutions are also responsible for upskilling instructors by providing training on best practices for online education delivery, ensuring that instructors are equipped with the necessary skills and strategies to effectively support students in the online learning environment.

5.4 Implications and future research

-

The design and delivery of the course

-

Accessing and utilizing the Internet and technology

-

Communicating online

-

Learning and studying in the home environment

-

Lack of peer interaction

-

Reduced motivation

-

Online assessments

The reviewed literature suggests a variety of strategies to mitigate these challenges, which are succinctly summarized and provide a valuable starting point for institutions and instructors to implement. However, given the range of stressors identified and the often vague strategies proposed, further research is needed to identify more effective solutions. To provide evidence-based recommendations to inform best practice, it is suggested that more research empirically test potential strategies that address identified stressors to produce an improved learning experience. Higher education is also a prime environment for codesigned research methods, providing students with opportunity to meaningfully contribute to their educational context.

5.5 Limitations of the current review

A limitation of the current review is that many of the studies included did not provide demographic information about the participants. Age, gender, personality traits, and prior academic experience can significantly impact how students experience online learning, as different groups of students may respond differently to various aspects of online learning. For instance, some studies have found that females experience higher levels of stress during online learning than males (Ertürk Avunduk & Delikan, 2021), whereas others have suggested that older students (>30) have greater self-efficacy beliefs around online learning (Morin et al., 2019). However, groups over 40 may face difficulties due to unfamiliarity with the technical aspects of online learning (Chen et al., 2020). Personality differences and prior academic experience (Baruth et al., 2021) can also influence students' experiences of online learning. Therefore, it is important to consider the influence of these variables to gain a better understanding of how they contribute to the stressors reported in this review. Future research should consider these variables to tailor online learning and content to meet the needs of different student populations. By doing so, educators can help minimize stressors and promote a more positive online learning experience for all students.

6 CONCLUSION

The present review identifies common stressors experienced by online students in higher education. Our findings suggest that online students face various stressors that impact their learning experience. It is crucial to consider these stressors and potential interventions when designing and delivering online courses. The present review has highlighted some of the main stressors that online students face, enabling educators and institutions to target improvements to their online teaching practice. These interventions could help reduce stressors and ultimately support the well-being and academic success of the growing online student cohort. Our findings have important implications for educational practices in higher education, and future research should explore additional stressors and interventions to enhance the online learning experience.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

John Mingoia: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft. Erin Skinner: Formal analysis; investigation; writing—original draft. Lauren Conboy: Formal analysis; writing—review and editing. Laura Engfors: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Brianna Le Busque: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics was not required as the paper is a systematic review of published literature.

Biographies

Dr. John Mingoia is an online lecturer in Psychology. He holds a PhD in Psychology, and his research interests include student well-being and academic achievement in higher education, body image, cancer prevention, health promotion, and the influence of social media.

Dr. Erin Skinner is a lecturer in Environmental Impact and Well-being in the College of Education, Psychology, and Social Work. She holds a PhD in Psychology, and her research explores the reciprocal relationship between humans and nature, particularly how nature can enhance student well-being.

Lauren Conboy is a Psychology PhD Candidate with broad research interests in attitudes toward cosmetic surgery and the impact of social media.

Dr. Laura Engfors is an online lecturer in Psychology. She holds a PhD in Psychology, and her research focuses on cognitive psychology, research methods, and psychometric assessment. She also investigates student well-being and academic achievement.

Dr. Brianna Le Busque is a Program Director in the STEM faculty. She holds a PhD in Psychology, and her research examines environmental psychology, particularly human relationships with the natural world, as well as strategies to enhance student experience and well-being.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.