Educators' perceptions of a system-informed positive education program: A study of most significant change

Abstract

There are increasing calls for positive education to integrate holistic and system approaches to both the understanding and implementation of mental health and well-being interventions across all levels of a school community. The purpose of this study was to examine educators' perspectives of the most significant changes that occurred at an Australian primary and secondary college following the delivery of a system-informed positive education program (titled Resilient IMPACT). A multi-stage evaluation was conducted, with educators providing written descriptions of the most significant perceived changes following program implementation, with 18 educators taking part in one of three focus groups to discuss these changes. Three main themes were identified from the focus groups: (1) Common and consistent language, which focused on the use of a language and communication framework for well-being conversations; (2) Consideration and empathy, where understanding of emotions and demonstrating empathy for students were stressed across interactions; and (3) Community commitment, which involved the building of a holistic community approach to well-being that is supportive and embedded in teaching practice. Findings support the need for holistic interventions in the school setting, focused upon the broader school community and a committed ‘well-being first’ approach to foster positive relationships amongst educators and students to support both academic and psychological outcomes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Schools provide an ideal setting for the introduction of approaches to encourage growth in student well-being, happiness, and resilience. Strength-focused approaches, where the aim is on building and encouraging the use of an individual's positive traits, characteristics, and behaviors (Allen et al., 2018; Allison et al., 2021; Raymond et al., 2018), have been operationalized through the field of positive education. Positive education draws on the principles of positive psychology (Waters & Loton, 2019), which examines the individual and systems factors that promote quality of life, well-being, and flourishing (Peterson, 2006; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). School-based interventions drawing on a strength focus have demonstrated efficacy in both reducing negative experiences and psychological distress (e.g., reduced student depression symptoms) and increasing subjective and psychological well-being (Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020).

Despite such promising findings, there is an emerging call within positive psychology to integrate greater complexity (Lomas et al., 2021) and system sciences (Kern et al., 2020) approaches to educational intervention. In particular, the need to move beyond a focus on building individual student capacities to developing positive education interventions that recognize the interdependency between students, their educators, and the broader school community has been highlighted (Kern et al., 2020; Lomas et al., 2021). As part of this, there is a need to ensure that interventions are intentionally designed and chosen based on desired outcomes within the particular setting, with implementation methods appropriate to capture those outcomes (Raymond, 2017, 2023). We refer to such whole-of-school interventions as system-informed positive education programs.

The purpose of the present study was to examine educators' perspectives of the most significant changes that occurred following the implementation of a system-informed positive education program. Adopting an educator-first perspective, this study specifically sought to identify the most significant changes that occurred following a 2-year implementation within one school setting. The study also sought to provide further evidence on the potential utility of whole-of-school approaches to positive education and to isolate key mechanisms to implement system-based programs designed to deliver positive well-being and resilience outcomes for children and young people.

1.1 Literature review

Growing evidence indicates that impaired mental health increases the propensity to experience mental illness, whereas high levels of mental health and positive well-being offer a level of protection for individuals (Iasiello et al., 2020; Keyes, 2013). While often considered to be at opposing ends of the same continuum, evidence indicates that mental illness and mental health can be independent of one another. Contemporary approaches therefore intend to reduce mental illness while concurrently improving well-being and mental health (Iasiello et al., 2019; van Agteren & Iasiello, 2020). Teaching young people strategies and skills to strengthen mental health and well-being can equip them early in life with skills to flourish, ideally preventing mental illness and improving whole-of-life outcomes (Norrish & Vella-Brodrick, 2009).

Positive psychology is an umbrella term (Pawelski, 2016) capturing a broad stream of theories and applications focused on strengthening human well-being and wellness (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). It represents a move away from solely attempting to reduce negative experiences or symptomology, which has been characteristic of more traditional psychological approaches (Carr et al., 2021; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Instead, the focus is building the strengths, virtues, beneficial conditions, and processes that contribute to well-being and positive functioning (Green & Norrish, 2013; Norrish et al., 2013; Seligman et al., 2009). Interventions within positive psychology focus on building positive emotions, cognitions, and behaviors, such as increasing gratitude, optimism, mindfulness, hope, kindness, compassion, relationship-enhancing behaviors, meaning, and goal setting (Boiler et al., 2013). Meta-analyses support the use of multicomponent interventions for increasing subjective and psychological well-being and reducing distress, with small to medium effects based on the outcome domain studied (Boiler et al., 2013; van Agteren et al., 2021).

Positive education operationalizes the key principles and methods of positive psychology across school communities (Waters & Loton, 2019). Like positive psychology more generally, which focuses on building positive emotions, experiences, and institutions (Carr et al., 2021), positive education highlights the importance of moving beyond a focus on academic achievement in school settings (O’Shaughnessy & Larson, 2014). Indeed, it is suggested that a focus on well-being can have positive effects both in and of itself, as well as for academic outcomes. While there is some contention regarding the relationship between student well-being and academic achievement (Kaya & Erdem, 2021), positive education interventions that take a holistic approach to education have been found to increase both well-being and academic performance (Bernard & Walton, 2011; McCallum et al., 2017; Shoshani & Steinmetz, 2014; Waters, 2011). Furthermore, a meta-analysis on multicomponent positive education interventions provides optimism that positive education can strengthen student mental health and well-being (Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020).

A criticism of positive psychology is that the focus of intervention is the individual (Christopher & Hickinbottom, 2008), and that traditional approaches do not take account of the complex interplay between the individual and broader environmental contexts. Instead, it is suggested that an individual's (in this case a student's) functioning can be best understood through the interaction of psychological and sociological determinants and interdependency between students, educators, and the broader school community (e.g., March et al., 2022). Indeed, adolescent mental health, well-being, and life satisfaction outcomes are mediated by a wide range of school and external experiences (Ciarrochi et al., 2016; McCullough et al., 2000). These include school climate, which involves aspects of the school experience such as school safety, peer interactions, and relationships with school staff (Aldrige & McChesney, 2018; Moore et al., 2017). To date, there are a range of examples of contextual factors being integrated within the design and implementation of interventions (e.g., trauma; Brunzell et al., 2016; Brunzell et al., 2021). However, this is not routine, and there remains a need to build a system-informed approach to positive education (e.g., Allison et al., 2021; Kern et al., 2020). A system-informed approach to positive education requires programmers, leaders, and educators to consider a broader range of possible outcomes, methods and processes, and to systematically embed them within a school setting (Kern et al., 2020).

In response to this need, Raymond et al. (2023) have proposed the construct of a ‘well-being-responsive community’; an approach for delivering mental health promotion in applied settings. The construct values the critical association between individual and community well-being (Atkinson et al., 2020), the impact of whole-school environment (e.g., school infrastructure, values, organizational governance, and policies) on both educator and student well-being (Biggio & Cortese, 2013), and considers the complexity of the environment (Hoare et al., 2017). The implementation of system-informed positive education interventions (such as a well-being-responsive community approach) requires educators, leaders, and programmers to contextualize positive education principles and methods across all levels of a school community (O’Connor & Cameron, 2017). This includes the strategic, or system level, of a school (e.g., well-being framework, policies, and procedures), the delivery of social-emotional learning and well-being curriculum (e.g., within classroom activities), and the responses to individual student needs and context (e.g., through supportive relationships and moment-to-moment exchanges, or teaching moments) (Raymond, 2023). Within the well-being-responsive community approach, a school community (consisting of students, educators, leaders, and families) is seen to have “the knowledge, language, methods, and skills to work side-by-side together to integrate best-practice science with their local knowledge systems and existing strengths and intentionally co-create contextualized wellbeing solutions at both the individual and community levels” (Raymond et al., 2023, p. 2). Previous research has examined the well-being benefits or outcomes of school-based positive education programs. However, as Waters and Johnstone (2022) state, there has been limited “scientific attention given to the processes schools employ to embed positive education” (p. 72). This means we know that interventions do work in such settings, but knowledge on the practical ways in which they can best be positioned and implemented (referred to as implementation science) in school settings is lacking (Forman et al., 2013).

An approach and set of methods that is purported to support a multi-leveled and contextualized operationalization is intentional practice. Intentional practice is conceptually and empirically grounded within three scientific disciplines: (1) trauma-informed practice, (2) positive psychology, and (3) implementation science. These early conceptual underpinnings (as detailed in Raymond, 2017, 2020; Raymond et al., 2019), and their multi-disciplinary applications, have been consolidated into a theory-to-practice approach (Raymond, 2023). Intentional practice is described as a “common language, approach and set of methods that is purported to support the design, adaptation and implementation of both simple and complex wellbeing solutions (from the ‘system’ to the ‘moment)” (Raymond, 2023, p. 2). The term ‘well-being solution’ represents an educator strategy, well-being plan, social-emotional learning program or whole-of-school well-being initiative that is designed to deliver a learning, growth, developmental, behavioral or well-being outcome. At its simplest level, intentional practice requests programs, systems, and educators to be mindfully aware of the intentions of a well-being solution (or intervention program, response, and strategy), including the desired outcomes and the methods of how they are achieved (Raymond, 2023). Across education settings, a critical question of intentional practice is ‘what is the intent of this well-being strategy, social-emotional program, and our moment-to-moment teaching support?’ Such an approach seeks to reduce the gap between scientific evidence regarding positive psychology efficacy and provide a framework for selecting, designing and, importantly, implementing well-being solutions (Cabassa, 2016).

Intentional practice conceptualizes schools as multi-levelled systems where smaller more targeted ‘well-being solutions’ (e.g., moment-to-moment support) are nested within larger and broader ‘well-being solutions’ (social-emotional programs and whole-of-school initiatives or interventions; Raymond, 2023). Other whole school approaches (e.g., Hoare et al., 2017) similarly highlight the importance of teaching specific positive psychology content, integrating it across learning (e.g., using its principles around strengths across academic subjects) and the community, and ensuring it is lived by members. This can be demonstrated in the ways in which teachers respond to student concerns, behaviors, and conversations (Hoare et al., 2017). The intentional practice approach provides a framework where the system (e.g., the school community) is aware of and shares the overall intent of the well-being solution and is focused on building the growth and well-being of its members. This is defined within intentional practice as educators and communities bringing a ‘growth intent’ to student support, or uplifting both intent and energy to student ‘growth’ or the building of student capacity for improved whole-of-life outcomes. This awareness and growth orientation finds its way into the components of the program and the moment-to-moment (e.g., teacher and student) interactions and relationships of members including the use of a common language around well-being (Raymond, 2023).

A key concern in the implementation of interventions is long-term efficacy, as well as the maintenance of systems and approaches that facilitate their uptake. One feature of intentional practice is the role of ‘stickiness’ (Raymond, 2023). In other words, scientific constructs or positive education principles and methods become ‘sticky’ in the minds, decision-making processes, and actions of individual and collective knowledge users whether they be teachers, students, or leaders. This means that key constructs are memorable and guide individual and community intent and actions after periods of more intensive implementation (e.g., training and coaching). Intentional practice has been operationalized across a range of applications, including multisite positive psychology programs (Raymond, et al., 2019), trauma-informed practice (Raymond, 2020), clinical interventions (Raymond, 2018), and the delivery of school-based social and emotional learning programs (Raymond, 2017). While offering promise within the operationalization of system-informed positive psychology programs (Raymond et al., 2018), the effectiveness and utility of intentional practice as a common language, approach and set of methods, and the degree to which it is ‘sticky’ in action remain largely unknown. This paper responds to this needed research direction (Raymond, 2023).

1.1.1 Rationale and aims of the present study

The present study sought to examine how the implementation of a systems-informed positive education program was taken up by a school community. It investigated educators' perceptions of the most significant changes that occurred following the implementation of a system-informed positive education program founded upon the language, approach, and set of methods of intentional practice (titled Resilient IMPACT) in an Australian school setting. The focus was not on specific components or well-being interventions or solutions (e.g., a particular positive psychology intervention such as gratitude practice) implemented by the school. Rather, the focus was on how integrated content on well-being, positive psychology, and intentional practice had been received, and what changes to the design and implementation of well-being solutions (and student support) had resulted from the program. It explored if, and how, the principles and methods of positive psychology and intentional practice had become ‘sticky’ and embedded in the educators' practices.

2 METHOD

2.1 Study design

This study applied a qualitative method underpinned by the Most Significant Change (MSC) technique developed by Davies and Dart (2005) as a form of “participatory monitoring and evaluation” (p. 8). MSC is an evaluation methodology that involves stakeholders sharing stories regarding the most significant changes they have observed following program implementation. The most significant of these stories, which are the ones that capture particularly important domains and reflect the goals of the project, are chosen by participants or staff cohorts.

The 10 steps outlined by Davies and Dart (2005) as the MSC technique were used to evaluate the Resilient IMPACT program. Steps 1–3 of the MSC technique involve starting and raising interest, defining the domains of change, and defining the reporting period. Steps 4 and 5 involve collecting and selecting most significant change stories. Steps 6–9 involve feeding back and verifying the stories with participants, quantification and secondary analysis and meta-monitoring. Revising the system is the final and 10th step of the MSC technique (Davies & Dart, 2005). Table 1 summarizes how, when, and by whom each of the MSC steps were conducted in this study with detailed procedural information provided below.

| Timeline | MSC step | Description | Method | Conducted by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 2021 | 1–3 | Raising interest, identifying domains, and defining reporting period (whole school staff) | Domains and reporting period mapped to implementation strategy and local well-being framework outcomes | Life Buoyancy Institute (LBI) Foundation in collaboration with Tenison Woods College |

| Mid 2021 | 4 | Collection of stories (n = 49). | Online stories of MSC | LBI Foundation and external evaluators (University academics) |

| 2021 | 5 | Identification of key stories | Thematic analysis of higher order themes | |

| 6 and 7 | Feedback and verification of stories (n = 3 focus groups, 18 participants total) | 3 × focus groups | External evaluators | |

| 8 and 9 | Quantification, retrospective analysis of themes | Thematic analysis of themes and subthemes | ||

| Late 2021 | 10 | Revising the system (whole school staff) | Collation of findings and discussion | External evaluators and LBI Foundation |

2.2 Setting and participants

Resilient IMPACT was implemented in early 2019 at Tenison Woods College (TWC), an independent co-educational Roman Catholic primary and secondary school. TWC is in Mount Gambier (population ∼30,000 people), a regional town located approximately 450 km from South Australia's capital city, Adelaide. Prior to program delivery, the school staff had been trained in foundational positive psychology content and trialed its translation across the school community. Based upon early learnings, they sought an integrated and sustainable approach by which positive psychology and well-being content could be embedded across all levels of the school community, as made practical through shared language, knowledge, skills, and methods (as captured by the well-being-responsive community approach; Raymond et al., 2023). The desired long-term program impact was improved student and educator well-being and resilience. The program had been running at the school for nearly two-and-a-half years when the evaluation reported in this paper began.

Participants for this study (the evaluation) were drawn from the entire school site (approximately 120 staff), including leaders and administration staff, junior, middle and secondary teaching staff, and staff teaching in specialized education programs. Staff were made aware of the evaluation and domains of interest (i.e., examining changes through the implementation of Resilient IMPACT) through consultation between LBI Foundation and the school community (Steps 1–3). Following this, a total of 48 educators (approximately 40% of site staff; n = 9 leadership staff, n = 23 middle and senior school teaching staff, and n = 17 junior school and special needs teaching staff) provided in written form a story of most significant change (Step 4), which were examined (Step 5) and informed the subsequent steps of the evaluation. Focus groups were undertaken to provide feedback and verify the stories (Steps 6–7). A total of 18 staff participated in one of three focus groups. Focus Group 1 consisted of five school leadership staff and staff with administrative responsibilities. Focus Group 2 consisted of seven educators from the junior school (Reception to Year 6) and special needs (inclusive education) teaching teams. Focus Group 3 consisted of six educators from the middle (Years 7–9) and senior school (Years 10–12) teaching teams. This paper reports the results of the focus group analysis (Steps 7–9), which was informed by the educators' written stories and subsequently informed the delivery of findings and discussion of implications to school staff (Step 10).

2.3 The Resilient IMPACT program

Resilient IMPACT is a capacity building program developed by the Life Buoyancy Institute (LBI) Foundation, a not-for-profit Australian agency that supports schools, agencies, and communities to sustainably embed evidence-based practices and intentionally deliver localized well-being, trauma, growth, and mental health outcomes (https://lbi.org.au). Resilient IMPACT has been operationalized by LBI Foundation through a logic model, as mapped to the long-term outcome of building a well-being-responsive school community.

The Resilient IMPACT logic model includes seven core implementation components that are designed to be individually contextualized to the school community. These components have been iterated and refined through multiple science-to-practice collaborations, including a large-scale and multi-disciplinary well-being and resilience skills program (Raymond et al., 2018). These components, their definition and their operationalization to the study site, Tenison Woods College school community, are detailed in Table 2.

| Core component | Definition | Local implementation outputs |

|---|---|---|

|

A codesigned implementation plan is developed with the school leadership team, which includes a positioning statement or local model that operationalizes Resilient IMPACT alongside existing well-being programs, frameworks and initiatives. This is then operationalized through a communication plan. |

|

|

All educators and support personnel receive foundational IMPACT training on the science of well-being, resilience, coaching, growth planning, how to respond to student needs, intentional practice, and side-by-side growth action planning. |

|

|

LBI Foundation provide wrap-around coaching and support to school leaders to implement the foundational IMPACT content across the entire school and classrooms, with this guided a scaffolded capacity building strategy. |

|

|

Local personnel are accredited as “IMPACT coaches” (additional training and online accreditation). They are supported to peer mentor, coach, and champion the work across the school community. |

|

|

A codesigned embedding strategy is developed to embed key IMPACT content, with a focus of finding an embedding point for What-What-How®, which operationalizes intentional practice and shared growth action planning. |

|

|

IMPACT coaches have access to additional resources, tools, videos, and modules to support embedding (including with students). All site staff have access to specialist workshops that take the foundational IMPACT content to specialist contexts (e.g., trauma, adolescence). |

|

|

LBI Foundation and site leadership conduct a dynamic action research review process to review and codesign the implementation strategy against a locally embedded evaluation process (most significant change). |

|

As noted in Table 2, Resilient IMPACT draws upon the content, resources, tools, and strategies of the IMPACT Program (https://impactprogram.net). IMPACT stands for Intentional Model and Practice Approach for Clients to Thrive. This capacity building program is purported to make the science of well-being, trauma, resilience, growth, coaching, and intentional practice practical, ‘sticky’, and translatable across broad communities, including for children, young people, and adults. A central embedding tool of the IMPACT Program is the What-What-How®. This is a structured reflective and growth planning tool to guide the intent of educators for student support and growth and to scaffold the conversations between students and educators. The method brings shared awareness to what is happening, what is important or the intent behind an approach (or well-being solution), and how one can act. This provided a structured and uniform approach to a diverse range of conversations and documented student and system-based planning processes, as made practical through a growth-focused practice approach (or educators acting with a ‘growth intent’). The What-What-How® is designed to operationalize intentional practice, coaching processes, codesigned growth planning and a range of positive psychology and well-being skills. In additional to this, IMPACT Program's content includes a range of broader positive psychology skills designed to be intentionally embedded across the school community, including mindfulness, growth mindset, brain functioning, value activation, self-regulation, goal setting and action planning, problem solving, and healthy communication.

The IMPACT program and its content were applied to operationalize numerous Resilient IMPACT core components, including foundational training (component 2), coaching processes (component 3), the community champion accreditation process (component 4), the embedding tools (component 5), and the resource library and workshops (component 5). While preliminary data have supported the practical utility of the IMPACT program to operationalize the contextualized delivery of well-being and resilience interventions (Raymond et al., 2018), this study is the first time it has been formally evaluated.

2.4 Most significant change procedure and data analysis

The evaluation process was undertaken over a period of 6 months (see Table 1), with some deliberate adaptations to the MSC method (e.g., in Step 7 generating deeper summary stories, as explained below). The contextualization of the evaluation process to the setting is an essential component of the MSC method outlined in Davies and Dart (2005).

Steps 1–3 were undertaken by LBI Foundation. The reporting period was defined from the point of initial implementation, and the domains of focus were restricted to “teaching or support practices” and “how the school thinks about and implements well-being”. These outcomes were linked to the desired outcomes of Resilient IMPACT, and the localized model for well-being developed for TWC. An information sheet provided to all educators invited them to provide their MSC stories and to participate in a focus group discussion.

“Looking back over the past two years, what do you think was the most significant change that has occurred in the Tenison Woods College community through the delivery of Resilient IMPACT? This could be related to your own teaching or support practices, or how the school thinks about and implements well-being”.

De-identified stories were provided by LBI Foundation to the external evaluator (University researchers). Thematic analysis was used to generate initial themes present in the stories, with a focus on the elements of the Resilient IMPACT program that participants identified as having been most important to their professional practice and the culture of the school. In order to do this, stories for the three groups (leaders/staff with administration responsibilities; junior and inclusive education staff; and middle and senior school staff) were examined separately. Stories were read and reread, with notes made to inform the generation of codes based on core concepts within the stories. Following this, preliminary thematic analysis was undertaken, with codes grouped according to common elements and themes generated based on the overarching patterns identified (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021). These themes, which consolidated the core content of stories, were used for feeding back to educators (Step 5).

Focus groups were then conducted where key themes were presented to participants for verification (Steps 6 and 7). During this process, participants were presented with the key themes identified in the initial thematic analysis and invited to reflect on or expand upon these themes and offer deeper summary stories that brought the theme alive in practice. This contextualized adaptation was undertaken to elicit richer story content, as per the MSC evaluation methodology. While the stories collected in the previous steps were separately analyzed for each group (leadership, junior and special needs teachers, and middle and senior teachers), very similar themes were generated for each group with no real group differences. Therefore, the themes provided to each focus group centered on the same themes of: consistency in language and approach; intentionality as a key aspect of their approach; and relationships, including how educators approach student interactions, their focus on building students' skills in these areas, and the impact of such approaches with students and/or colleagues. Using these themes for discussion, the three groups could consider to what extent these themes reflected their experiences and unique contexts. A facilitated and interactive discussion was held with participants using guiding questions such as ‘why is this story important for the school community, including the well-being of school personnel or students’? And ‘what have been some of the key enablers/barriers to embedding Resilient IMPACT within your school community?’. Each focus group was asked to think of examples that resonated with the group to capture the most significant change following the delivery of Resilient IMPACT at TWC.

The three focus groups were run via the Zoom Conferencing platform. The external evaluation team conducted Steps 8 (quantification of data collected) and 9 (retrospective analysis against subthemes). Focus group data were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2021). This included reading and rereading transcripts and recording initial ideas. Following initial consideration of the data, coding aspects of the data that reflected potentially important meaning was undertaken. Codes were clustered according to similarity and then the identification of potential themes within these codes was undertaken. Theme generation was focused on identifying shared meaning, ensuring there was enough focus and richness of data for a particular theme's generation, and that there were boundaries within each individual theme (see Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Based on considerations discussed by Braun and Clarke (2021), the analysis took a deductive approach, where data were analyzed according to the theoretical constructs within the Resilient IMPACT program and wider theory regarding positive education. The approach also focused on educators' experiences with attention to both more explicit concepts discussed and the underlying meanings reflected within them. Once this analysis was undertaken, further coding and meta-monitoring (step 9) took place. This allowed the evaluation team to revisit the entire MSC stories and statements from the preliminary identification of stories (step 5). Revisiting these stories allowed a deeper focus upon the origins of the initial statements shared, from which participant cohort they originated, and the relevance to the transcribed stories that were collected from each focus group cohort and the community as a whole.

Both direct and indirect results of the implementation of Resilient IMPACT upon TWC and the broader school community have been considered. Combining the contextual and program expertise of LBI Foundation staff with external evaluators was undertaken to account for any inherent biases encountered in a purely internal evaluation (if all steps were conducted by LBI Foundation).

2.5 Ethics and site approval

Ethics approval for the research was granted by CQUniversity Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2021-038), with approval to conduct the study at TWC provided by the school principal.

3 RESULTS

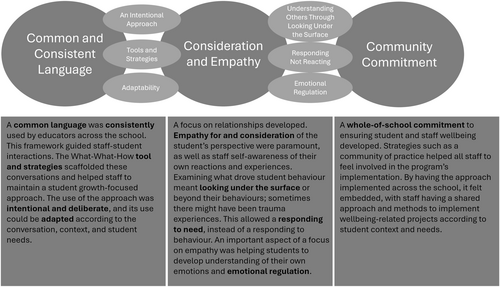

Three main themes (with related subthemes) were identified from the focus group data: (1) Common and Consistent language, (2) Consideration and Empathy, and (3) Community Commitment. Figure 1 demonstrates how each of these themes fit together, each building upon and interacting with one another. Below, we discuss each theme in detail.

Themes from the most significant change validation for Resilient IMPACT implementation and acceptance at TWC.

To prevent the identification of individual staff, specific roles, demographic (e.g., gender, age) and experience (e.g., years in a role) details are not reported, and all participants are referred to as educators. Quotes are denoted in the following way with a participant number: leadership and administration (LA); junior primary school (JP); and middle-senior school (MS) groups.

3.1 Theme 1: Common and consistent language

The first theme, involving communication across the school community, was demonstrated in the adoption of common and consistent language following program implementation. Across all three focus groups, participants spoke of the conscious use of a framework of common language and how a consistent form of communication was being used across the school, “It's both of those things [common and consistent language] that have worked together to make it [the program] successful, I think” (JP5). Participants noted that key drivers of the adoption of the consistent approach to communication were staff who make up the well-being team. These members provide coaching and mentoring to educators to embed the Resilient IMPACT program content and tools across the school and support services to students. One participant reflected that “over the years [of implementation] the team has grown to be really strong and not a ‘yes’ team, but a very collaborative team” (LA4). This team was trained and coached to empower other staff to explore and apply the program's language, methods, and tools.

3.1.1 Tools and strategies

The use of a common and consistent language, founded upon intentionality, was facilitated by the wide acceptance of the What-What-How® tool. The tool was seen to give structure and purpose to conversations across the school community. For example, the approach could be used within the classroom, in conversations with students and their families, and in diverse contexts such as in extracurricular (e.g., sport) activities. Participants across the leadership/administration, junior, and middle-senior school educator groups all reflected on the prevalence of the use of the What-What-How® approach within the school. This was due to its flexibility, where it could be tailored to the particular developmental level of the student or classroom but still retain its core structure to approaching conversations, “I think the other part is that there is a real strength in the simplicity that it can be used at a strategic level” (JP6).

The ability to use common language and the What-What-How® tool came about because the approach had been introduced across the school community. That is, it was not only the educators using the language, but students understood the language and were able to use it to articulate problems or issues themselves. The approaches were used with different conversations and were seen to lead to more tangible outcomes. One staff member reflected, “If we've got a staff member that is meeting with a family, we just ‘What-What-How’ it out, so that language for the last 15 months really has started to improve [communication] and it is feeling a lot more comfortable” (LA4). Another participant explained that this tool had provided that strategic and directed approach to conversations, “because conversations can, as we know, if we have an open floor with no structure, become just more of a conversation, or paralysis by analysis more so than necessarily moving forward with a bit of direction” (LA5).

3.1.2 An intentional approach

Educators and leadership staff identified that the Resilient IMPACT embedding tools and strategies had been widely accepted and integrated into practice in a deliberate, thoughtful, and ‘intentional’ way. They spoke of how a consistent language, utilizing the tools within Resilient IMPACT, facilitated communication and conversations with students that were ‘intentional’ and focused on and recognized student strengths. For one participant, “A growth intent is something that we adopt in our conversations with students, and we focus on their strengths in what they can do, what they can show in their learning, not what they can't show” (MS5). The use of an intentional approach was evident across both day-to-day teaching and wider considerations around approaches to learning at the school. Being mindful of fostering a growth intent was evident in numerous classrooms, where “It is even to the point where you walk into a classroom and you can see on the whiteboard, they could be using it [What-What-How] for a lesson outliner, to get that learning attention more effectively, so it's used on a range of different levels” (LA2). One educator suggested that alongside the use within classrooms, it aided more general educative practices: “I have also applied it [What-What-How] to my teaching pedagogy as well in trying to address the best way to approach teaching students so that they are not sort of spoon-fed teacher lines” (MS3).

Participants did highlight a challenge in continuing to consciously use the approaches from Resilient IMPACT, where it could be “easy to fall back into old habits” (JP4). In addition, as staff leave the school and new staff take those roles, ensuring that training occurs for new staff and refresher training continues for existing staff was deemed important. However, the model of training staff as coaches was seen as a way to maintain continuity, “[This] is how the model works that once we are coaches then we are then coaching the people that are just starting” (MS3).

3.1.3 Adaptability

The adoption of the Resilient IMPACT core components was enhanced by their simplicity and their adaptability to a wide array of student situations and teaching approaches. The components could be used with students across the school: “I think that it is simple enough that it is adaptable across the school; it's not a framework that works just for younger children or older children it is very adaptable; it is adaptable to all year levels, and it does give us a launch pad to work with kids in a more positive manner” (JP3). Participants noted that the embedding tools and strategies had helped flow to occur within their conversations, with one participant sharing; “It is a pretty simple approach that can cascade to become more complex; it helps us name issues but move forward” (LA1). Participants further reflected on how the common language afforded by the approach resulted in its use in student–staff interactions as well as staff–staff interactions, “It might have been to tackle a certain issue that might have come up [with a fellow educator] and likewise I have used that very same language to guide meetings with senior school students around their learning needs” (MS2). By the nature of its adaptability and the intentional implementation by the school, educators noticed that they could use what they had learned with student behavioral concerns, in their planning and delivery of well-being content, and even for reflecting on their own teaching practices.

3.2 Theme 2: Consideration and Empathy

The second theme, Consideration and Empathy, reflected awareness of the centrality of empathy and having a deeper understanding of others and oneself when interacting with students and other educators. Participants spoke of a significant change in their awareness of the importance of acknowledging not only their own perceptions and inherent assumptions (e.g., about student behavior) but also interrogating others' perspectives. One participant modeled the language that could be used when addressing a student well-being-related concern, “I wonder how you are feeling about this. I have noticed that this is happening. I am curious about this behavior. Can you tell me what it is doing for you and why you might be behaving this way?” (JP3).

Several participants reflected on the benefits of curiosity and consideration of others' perspectives, both for their own interactions with students and also for students' relationships with one another. Some participants who taught within the younger year levels (junior school staff) suggested that much of their teaching involved a relational approach, whereas they believed teaching in the more senior year levels was more focused on curriculum and academic content. However, middle-senior school participants referred to several initiatives related to relationship building, such as a particular focus over a year of building skills around empathy, mindfulness, resilience, and deeper relationships in the Year 9 cohort; while student retreats in later years deepened student relationships and connections with one another. Participants from the school leadership group, who discussed overall school impacts, felt that a focus on empathic relationships ultimately resulted in a student-focused approach, “The staff not once thought about themselves, they thought about the learners in front of them and it was just so student focused and that's probably a big example of change” (LA4). An added benefit of this empathic approach was more productive relationships with families, “What I've been able to do is talk to these parents and just unpack with them … what feelings might be fueling [the student's behavior] and then I've talked to them about what we can do together is to create a growth action plan” (JP5). This empathic approach was facilitated by looking under the surface, responding rather than reacting to student issues and helping students to self-regulate their emotions.

3.2.1 Understanding others through looking ‘under the surface’

We are finding out and recognizing what is going on for the student; it's certainly encouraged you to see beyond the nature of your interactions in the classroom so I've found it [empathy] useful to support thinking deeply about what is going on and when to recognise where there were gaps and try to work out how we can bridge those gaps to enhance the learning (MS4).

Participants identified that it was important to ensure students felt “heard” (MS2) and were “given a voice” (MS4). Similarly, it was important to be aware of what colleagues could bring to a conversation or situation with each staff member potentially “bringing a new lens on how we can approach situations” (LA4). Remembering “that we are all together and … we are working for the same goal for each of the students” (JP3) was particularly important to ensure different perspectives were valued and used when working to positively affect student well-being.

I think teachers have become more aware that there is often a reason or feelings often fuel this behavior so that has been a bit of a change … often there is a trauma aspect or trauma-based reason as to why a behavior is occurring (JP5).

You have actually gone underneath the surface to find the things that are happening, and they can see it in action, they have witnessed it, they believe in you, and they trust you that you are going to do that for them (JP7).

3.2.2 Responding not reacting

They [students] need to feel valued and that is something that we have done as responsive teachers, making the students feel valued, but then again naming that [show of empathy] in the classroom you know what they are saying to you at that point in time really matters, and that whole feeling of connection within the classroom (MS6).

3.2.3 Emotional regulation

Participants shared that a significant change at the school was an enhanced sense of understanding how to support students to develop emotion regulation skills. Supporting this change, participants identified emotional regulation as being about helping students recognize who they are and their place in the broader system, building upon positive language, and encouraging them to develop a growth mindset regarding self-regulation. Participants referred to being “growth oriented” (LA1), with one participant reflecting, “We are being very proactive in responding to help a child to develop social skills” (JP7). Emotional regulation and related skills were seen to be important across cohorts, but there were different needs depending on the cohort. In the junior levels, goals centered around young students learning about their emotions and developing greater emotional understanding. Within the more senior levels, this was widened to include students' consideration of their identity and place in the world. Empathy and understanding were aided by using a common language, “I guess that language has really fitted in with the way that we are practicing at school in that we are trying to tackle both behavior and any academic challenges that the students may face” (MS4). Specifically, skills and attributes that contribute to positive well-being had become a part of the language used in conversations with students, “it’s bringing ‘empowerment’ to students through a year-long focus where mindfulness, empathy, great achievement, and resilience, where that language is explicitly taught now” (LA5).

Common language also allowed a deeper collaboration amongst educators, with acknowledgment that a focus with students on an “I see you; I hear you” (MS5) empathic approach had become more “sharpened and natural” (MS5). Well-being discussions were approached to consider words used, body language expressed, and tone of voice used to convey messages effectively. A key aspect of this was regulating one's own emotions, considering things objectively, taking a step back where needed, grounding oneself, and being aware of how one's own well-being or resilience may have been impacted following a school incident.

3.3 Theme 3: Community commitment

The third theme of community commitment involved commitment to working together and responding to student and staff well-being needs proactively, sharing and connecting with one another, and having an all-school well-being first approach to staff and student interactions. Across focus groups, participants spoke of this whole of school commitment, including investment of senior leadership, in particular the principal, in embedding of practices across the school community. The principal was described as a “key enabler” (JP5) and senior leadership as having “role modeled” (JP4) the approach. This was seen to have resulted in spreading the message of a well-being focus and providing a ‘mechanism for change’.

Participants found that an approach that fostered community commitment was a Community of Practice exercise performed with all educators. As participants described, these were forums facilitated by LBI Foundation that focused upon addressing systemic needs that impact upon the wider school community. Educators suggested these forums provided an opportunity for them to do what they already do better by allowing them to come together and identify in groups well-being projects to embed the Resilient IMPACT framework within different sections of the school going forward: “I think it has raised awareness of how important it is to have really authentic meaningful relationships and I've seen LBI has just enhanced the communication between us as professionals; the collaboration is there, and it is really authentic meaningful collaboration” (MS5).

When we're walking side by side with a student there might need to be a time when you need to take back over the [aeroplane] controls and actually just give them some down time, some calm time and then it's just like a gradual release of responsibility where you are working side by side to coach them through a situation to skill them for when the plane starts falling out of the sky the next time (JP5).

Another initiative involved creating growth action plans for students in the younger year levels. The importance of including staff as much as practical was reflected so that uptake and commitment to the approach were maximized, “Having the time to get all of our staff involved so that they feel they have a little bit of ownership over the creation of it is important, so that they don't feel like they are just reading a document and implementing it without being part of the process” (JP1).

When I think of significant changes, that has been in the mindsets with our teaching approaches across the college, where we have been very mindful of our students and their needs and having that student centred approach with our daily interactions with students. Our interactions in the classrooms have been enhanced and focusing not only on the learning that is going on in the classroom but also the needs of the students in that environment, looking a bit deeper under the surface and understanding why and how students are surviving, or coping and what might be some of the triggers, or what might be some of the causes for a particular response, or a particular reaction. The most significant change from our LBI work and Resilient IMPACT work is positive change within our teachers, and our relationships and our interactions with students both in and outside of the classroom, and it's what I see occurring on a daily basis (MS4).

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine educators' perspectives of the most significant changes that occurred following the implementation of a system-informed positive education program. Specifically, it provided a qualitative exploration of the implementation of one such program, Resilient IMPACT, in an Australian school setting. This program was designed to support the development of shared knowledge, language, skills, and methods to build a well-being-responsive community (Raymond et al., 2023). The evaluation sought to determine if, and how, the principles and methods of positive psychology and intentional practice (as implemented through a whole-of-school or system-based approach) had become embedded in the educators' practices.

Positive psychology interventions in the school setting have demonstrated efficacy for improving student well-being (Waters, 2011). However, they have often been criticized for focusing on changes in individuals without considering the context in which a young person is living or learning (e.g., Allison et al., 2021). There is also concern that outcomes (e.g., changes on well-being measures) are the focus rather than the processes—or how—a positive education or well-being solution works (Raymond, 2023; Waters & Johnstone, 2022). The present study attempted to understand the well-being practices that have had the most impact upon the broader school community, as perceived by educators.

The three most significant changes that the intervention produced were identified as a common and consistent communication, a focus on empathy, and a whole-of-school approach to well-being. Within each theme (or significant change), there was evidence that an intentional approach was being enacted through consistent language and focus on forming positive and productive relationships with students and fellow educators. Furthermore, aspects of the IMPACT program were being embedded in practice, complementary to curriculum. These outcomes align to the stated impact of the program (well-being-responsive community), with the intentional practice approach facilitating a framework for relationships between students and educators and the wider school community.

The importance of shared language around well-being and related concepts has been discussed within the wider positive psychology and positive education literature (e.g., Jones & Bouffard, 2012; Linley et al., 2006). In the present study, educators reflected that a common and consistent approach to methods of communication had occurred after implementation, supported by the embedding of the What-What-How® or intentional practice approach. Shared language provided a tool for teachers to become intentional in their practice and interactions with students, mindful of what they wanted to achieve from well-being conversations or teaching moments. This reflects a wider approach within teacher education to move from a focus on building teacher content knowledge to impart to students to a focus on the purposes and goals behind particular teaching behaviors (Brunzell et al., 2019; Kennedy, 2016).

Within other positive psychology intervention studies, shared language was found to support the collaborative processes between educators and students related to well-being content (Waters & Johnstone, 2022). In the present study, the use of the What-What-How® tool in particular supported consistency between staff and assisted in “embedding and sustaining a culture of wellbeing” (Hoare et al., 2017, p. 63) across different year levels and educators. As reflected by participants, the acceptance of a common language and framework facilitated a shared intent where educators and students could communicate to implement well-being solutions. Shared intent and collaboration have been identified as foundational to responding to complexity across school settings (Raymond, 2023), as well as being a predictive factor in reducing teacher burnout and promoting educator retainment (Kingsford-Smith et al., 2023).

Positive educator–student relationships are commonly characterized by empathy and understanding, as well as low levels of relational disagreement (Davis, 2003; Roorda et al., 2011). In the present findings, these processes were seen as vital to how well-being solutions were implemented and the approach to student–educator interaction. Educators reflected on the development of the mindful awareness of the significance of perspective taking and empathy. The findings indicated that educators' behaviors and attitudes (for example explicitly acknowledging the importance of positive well-being and resilience) have changed as a result of Resilient IMPACT. Envisioning how another person might understand a specific situation requires entering into that other person's framework for interpreting the world and seeing their behaviors from their vantage point (Batson et al., 1997; Gerace et al., 2015). Such perspective taking can lead to more care and concern for that person and a desire to help (Gerace, 2018).

The focus of participants on empathy and understanding reflects a move toward considering well-being rather than a sole focus on academic outcomes (e.g., O’Shaughnessy & Larson, 2014). In particular, participants in the present study reflected on the need to more deeply appreciate what students might present with each day at school, including how trauma might play out in interactions within the school setting (Brunzell et al., 2019). Extensive evidence suggests that students who feel valued, understood, and encouraged by educators experience beneficial behavioral and cognitive outcomes (Cornelius-White, 2007; McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015; Roorda et al., 2011; Vandenbroucke et al., 2018). In addition, as noted by Keyes (2013), good relationships contribute to good mental health. Empathy is a process involving effort, and indeed, this aligns with the intentional approach to student well-being advocated by Raymond (2023). The Resilient IMPACT program also aligns consistently with positive psychology coaching principles (Biswas-Diener & Dean, 2007), facilitating a collaborative approach and relationship to identifying well-being focused approaches for staff and student interactions. Support to build relationships with students has been associated with greater educator well-being (Hargreaves, 2000; Shann, 1998), and the present study suggests that encouraging empathy skills and teachers' acknowledgment of how student concerns (e.g., trauma) impact them is central to building such connections.

Another change highlighted by educators was a more explicit focus on student growth and development of skills around emotional regulation (or acting with a ‘growth intent’). The importance of growth and strengths-based approaches with young people in school settings have been supported in previous work. For example, Brunzell et al. (2019) suggest the importance of introducing such concepts in a deliberate manner, reinforcing the concept in subsequent interactions and encouraging students' understanding and application of the concept. In the present investigation, language and the tools provided were a primary way to reinforce learning and encourage student growth.

The study provides further support for the need to consider the intricate relationships between people and their surroundings, as understood by an integrated social-ecological system perspective (Guerrero et al., 2018). The Resilient IMPACT program brought an outcome focus to the building of a well-being-responsive educational community, a system-based approach to individually respond to all community members' ’needs founded upon intentional practice. The intentional approach was demonstrated to have been embedded across the school with methods of collaboration discussed that facilitated staff buy in, in particular a community of practice approach. In a systematic review, March et al. (2022) identified several enablers and barriers to sustaining well-being interventions in school settings. Prioritization of the program and support by leadership, commitment of individual staff, inclusion of parents, understanding of the potential benefits, adequate resources, and the fit of the program to the school were seen to facilitate the sustained nature of programs. In the language of intentional practice, these are factors that contribute to the stickiness of the set of methods across the systems of the school community (Raymond, 2023; see also White, 2016).

In the present study, the frameworks and approaches introduced facilitated a well-being-responsive community to develop in the language used, shared intent around well-being, and the development of relationships. While participants reflected on few barriers to the implementation of program principles, there were indications of the need to truly embed and involve all staff in processes and the program itself needing to be seen as a long-term strategy to student well-being. To support the implementation of positive education interventions within the school setting, it has become increasingly evident that the education policymakers need to allocate the resources and time to allow for such interventions to enhance teaching practices and consequentially enhance well-being. Particularly important to educators in the present study was the embedding of well-being into activities across the school, both those related to facilitating well-being and general academic requirements (Hoare et al., 2017). Educators need forward-planning leadership, who support the allocation of educators' time to learn, embrace, and reach a level of acceptance in their daily practice.

4.1 Strengths, limitations, and future study directions

The study had several strengths and limitations. The focus groups and written reflections identified through the MSC approach prompted rich discussion amongst all educators who took part in the study. The study considered the how of positive education and well-being solution implementation (Waters & Johnstone, 2022). The most significant change approach (Davies & Dart, 2005) allowed for participants to actively construct what they believed were the most significant changes within their school community.

Despite these strengths, the nature of method and the sample needs to be considered. The study method, which involved analyzing dominant themes and then reporting these back to the focus groups for exploration, may mean that other perceived (but lesser documented in written stories) changes were not discussed. Involvement in the study was also voluntary and involved focus group participants being known to each other so there is a possibility of positivity bias with only those educators satisfied or supportive of the intervention choosing to participate. Participants raised few barriers to implementation in discussions, and this may be due to reluctance to go ‘against the group’ or raise concerns, or that educators more willing to participate felt positive about the program's implementation. Future studies could incorporate other approaches to evaluate the impact of the approach. This could include individual interviews to mitigate the reluctance participants could have to raise concerns or provide negative feedback within a focus group setting.

Rich data were obtained on educators' perspectives of what changes had followed the implementation of Resilient IMPACT. However, the chosen methodology of most significant change provided a lesser exploration of specific experiences and attitudes toward the Resilient IMPACT approach, including initial implementation challenges or barriers, how issues were addressed, and specific ways that positive psychology content was delivered utilizing the program's frameworks. Related to this, while the study was concerned with perceptions of change and the processes that had been taken up by educators, an important component of positive psychology evaluations is change on well-being and related outcomes (van Agteren et al., 2021). The extent to which changes in well-being and related factors have been evidenced is needed to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the rollout of the program. Taken together, future studies examining more specifically perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes of staff toward the initiative, and influences on indicators of well-being (e.g., changes in psychological and subjective well-being; student and staff engagement) within school communities are needed.

The study deepened the understanding of the perspectives of educators regarding positive psychology interventions. However, educators are only one group within a well-being-responsive community. Future work should consider the perspectives of other members of the well-being community, including students and parents and guardians. It would be particularly useful to see if the language used by students and educators was perceived to be useful or understandable to parents' thinking about well-being.

Initial results are promising regarding staff uptake post-initiation (or ‘stickiness’). Evidence of longer-term effects and sustained changes would need to be investigated. Indeed, this remains a challenge in the wider positive education and positive psychology intervention space, where outcomes are often assessed shortly after program rollout. Examining the ways in which sustainability (March et al., 2022) has been facilitated or compromised is needed. What remains important is that educators continue to build upon their framework, connections and relationships with one another and students, and prioritize a well-being focused approach to decision-making with regular community of practice reiterations into the future.

Finally, the evaluation focused on only one school; therefore, findings may not be generalizable to other schools where the program may be used in the future. Future evaluations of other schools involved with the Resilient IMPACT program would be beneficial in understanding the benefits or challenges that are maintained or developed across sites, as well as the potential for examining efficacy on various well-being-related metrics.

5 CONCLUSION

The present study revealed several positive impacts of a system-informed positive psychology education program across a large educational community. This provides evidence for the benefits that can be gained from positive education programs operationalized through a system-based lens (well-being-responsive community) and that are implemented through an intentional mindful approach. It has highlighted the importance of a holistic approach to student well-being and school experience involving the broader school community for positive change. Examining the ways in which well-being solutions are used by educators within the school community helps us to further understand the ways in which positive education approaches can achieve valued and long-term changes to well-being and the ways in which we can attempt to facilitate well-being and mental health in young people.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Stephen Burrowes: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Adam Gerace: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Tessa Benveniste: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Karena J. Burke: Conceptualization; formal analysis; writing—review & editing. David Kelly: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; writing—review and editing. Ivan Raymond: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank David Mezinec, Principal, Tania Sigley, Well-being Director, and the leaders, educators, and support staff at Tenison Woods College. Tenison Woods College provided funding to LBI Foundation to deliver the Resilient IMPACT program, including a review process. No direct funding was provided for the evaluation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Ivan Raymond is the co-director of LBI Foundation and declares receipt of payment for training packages and resources related to programs referenced in this article. David Kelly is the project lead for the Resilient IMPACT program. Neither author was involved in the data analysis and interpretation of findings.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval for the research was granted by CQUniversity Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2021-038), with approval to conduct the study at TWC provided by the school principal.

Biographies

Stephen Burrowes completed this research project as part of his Master of Applied Positive Psychology course at CQUniversity. Stephen has worked in senior leadership within the human services sector for over 20 years.

Adam Gerace is a Senior Lecturer and Head of Course for Positive Psychology at CQUniversity. Adam's research examines empathy and perspective taking, in particular how these processes influence mental health, well-being, and relationship outcomes across a range of contexts.

Tessa Benveniste is a Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow at CQUniversity and a provisionally registered psychologist. Tessa's research evaluates how educational and health systems can support well-being across multiple contexts, including rural and remote communities, boarding schools, and youth-focused residential care settings.

Karena J. Burke is an Associate Professor in Psychology and Head of the College of Psychology at CQUniversity. Karena's work is focused across a diverse spectrum of social activity aiming to promote the understanding of individual, organizational, social, and community level determinants of health and well-being.

David Kelly is the Education Lead with Life Buoyancy Institute Foundation. David is an experienced leader, service designer, and community researcher with a 30-year commitment to working with young people and communities to improve well-being and mental health outcomes and he served as South Australia’s Mental Health Commissioner from 2020 to 2023.

Ivan Raymond is the Clinical, Research and Education Director of Life Buoyancy Institute Foundation. Ivan’s work is focused on intentional practice as a language, approach, and set of methods to build well-being and trauma responsive local communities.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Request to access the transcribed data for research purposes can be made to the corresponding author.