Sensitivity of six subantarctic marine invertebrates to common metal contaminants

Abstract

A long history of anthropogenic activities in the relatively pristine subantarctic has resulted in areas of accumulated waste and contaminants. Sensitivities to metals of subantarctic and Antarctic species may contrast with related species from temperate and tropical areas because of the unique characteristics of polar biota. In addition, response to contaminants may be delayed, and hence longer exposure periods may be required in toxicity tests with polar species. In the present study, the sensitivity of 6 common subantarctic marine invertebrates to copper, zinc, and cadmium contaminants was determined. Large variations in sensitivities, both between species and between metals within species, were found. The bivalve Gaimardia trapesina and the copepod Harpacticus sp. were the most sensitive to copper, with 7-d median lethal concentration (LC50) values for both species ranging between 28 μg/L and 62 μg/L, whereas the copepod Tigriopus angulatus was the most tolerant of copper (7-d Cu LC50 1560 μg/L). Sensitivity to zinc varied by approximately 1 order of magnitude between species (7-d LC50: 329–3057 μg/L). Sensitivity to cadmium also varied considerably between species, with 7-d LC50 values ranging from 1612 μg/L to >4383 μg/L. The present study is the first to report the sensitivity of subantarctic marine invertebrate to metals, and contributes significantly to the understanding of latitudinal gradients in the sensitivity of biota to metals. Although sensitivity is highly variable between species, in a global comparison of copepod data, it appears that species from higher latitudes may be more sensitive to copper. Environ Toxicol Chem 2016;35:2245–2251. © 2016 SETAC

INTRODUCTION

Human presence in the subantarctic over many decades has resulted in a number of contaminated areas 1. Legacy contamination sources include old refuse sites and fuel spills, as a consequence of past practices such as seal and penguin harvesting, whaling, and farming 1, 2. Current practices continue to generate contamination; the increasing shipping as a result of tourism and fishing results in elevated risk of fuel spills and shipwrecks, while research stations generate everyday wastes and contamination 2. Elevated concentrations of hydrocarbons and metals have been reported in areas associated with fuel spills and legacy refuse sites around subantarctic stations 3, 4. However, there is little information on the concentrations of contamination entering marine environments from these areas, or on contamination concentrations resulting from spills and accidents at sea 1.

Copper, zinc, and cadmium are 3 of the most common metal contaminants that occur around subantarctic and Antarctic stations 3-5. Copper and zinc are essential trace metals for metabolism in many marine invertebrates. Copper is involved in the respiratory system of many marine mollusc and arthropod species, whereas zinc is a key component for many enzymes. Therefore, these metals are not immediately excreted or detoxified. In contrast, cadmium is a nonessential metal and consequently needs to be detoxified immediately 6. All of these metals can become toxic above a threshold concentration 6.

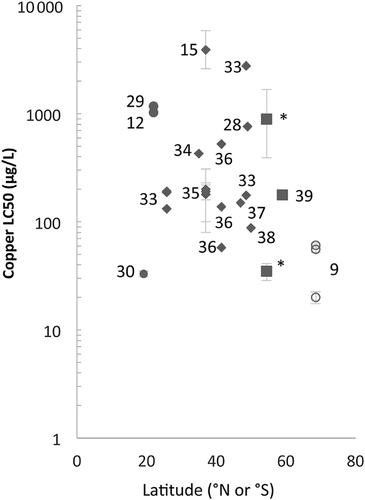

There is increasing evidence that the sensitivity of biota varies latitudinally; hence water quality guidelines developed in tropical or temperate areas are not suitable for polar regions 7-10. Organisms in high latitudes have adapted to stable and very cold temperature regimes and this is likely to influence their tolerance of contamination. In these regions, organisms usually exhibit slower metabolisms, live longer, grow to larger sizes, and have higher lipid content in tissues 10. In addition, environmental recovery time after large contamination incidents may also be longer because of longer larval periods and lower fecundity in many species. From the few studies conducted, in comparison with low-latitude biota, high-latitude biota may be more susceptible to copper, but be of less or similar susceptibility to cadmium or zinc 8, 10. However, insufficient data are currently available to confirm these trends 8, 10. Many subantarctic islands that have undergone long-term habitation are in need of the establishment of specific subantarctic water quality guidelines. In addition, areas such as the Antarctic Peninsula and southern South America, some of which are under high contamination pressures and have climates similar to those of subantarctic islands, would also benefit from the development of subantarctic region-specific guidelines.

Because of the unique biology of high-latitude marine taxa, there is a need to develop specific methodologies for toxicity testing. Time of exposure to metals is one of the most important considerations in modifying test procedures. Acute toxicity tests with temperate and tropical species are usually conducted over 2 d to 4 d, whereas tests conducted with Antarctic biota require up to 1 mo to elicit a toxic response and to enable comparisons with the sensitivity of biota from other regions 7. For example, the effects of metals on the development stages of the Antarctic sea urchin, Sterechinus neumayeri were tested over 23 d, because this is the time taken to reach the pluteus larval stage; in contrast, temperate species reach the same developmental stage within 2 d to 3 d 7.

In the present study, we established toxicity test methodologies, including relevant exposure periods, and determined species sensitivities to metals of 6 subantarctic marine invertebrates. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report the toxicity of metals to subantarctic marine invertebrates. Specifically, we tested the toxicity of copper, zinc, and cadmium to the following taxa: copepods Tigriopus angulatus (Lang) and Harpacticus sp. (order Harpacticoida, family Harpacticidae); flatworm Obrimoposthia ohlini (Bergendal; order Tricladida, family Uteriporidae); bivalve Gaimardia trapesina (Lamarck; order Veneroida, family Gaimardiidae); sea cucumber Pseudopsolus macquariensis (Dendy; order Dendrochirotida, family Cucumriidae); and sea star Anasterias directa (Koeler; order Forcipulatida, family Asteriidae).

METHODS

Study site and species

Tests were carried out on biota native to the subantarctic Macquarie Island, which is located in the Southern Ocean, just north of the Antarctic Convergence (Figure 1). Macquarie Island sea temperatures are relatively stable throughout the year, with average temperatures varying a few degrees, between approximately 4 °C and 7 °C 11. Sites chosen for the collection of invertebrates for the present study were free of metal contamination, as verified by the analysis of seawater samples from collection sites by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Varian 720-ES). Metal concentrations at sites were either below detection limits or <10 μg/L for all metals except cadmium, which had levels generally between 5 μg/L and 15 μg/L.

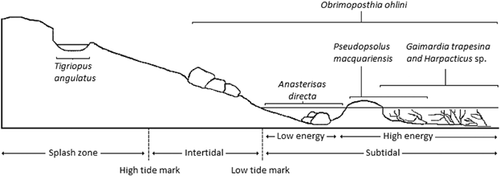

Six common invertebrate species representing a range of taxa were selected for use in toxicity tests and collected from different habitats on the rocky shore (Figure 2). Tigriopus angulatus were collected using fine mesh dip nets from rock pools above the high tide mark; Harpacticus sp. and G. trapesina, from several macroalgae species in the subtidal zone; O. ohlini, from the undersides of boulders from the intertidal to subtidal areas; P. macquariensis, from wave-exposed rocks; and the sea star A. directa, from deep rock pools (Figure 2).

Toxicity tests were conducted at Macquarie Island (over the 2013–2014 summer) and at the Australian Antarctic Division in Tasmania, Australia (from 2012 to 2015). Invertebrates for use in tests in Australia were transported by ship to the Marine Research Facility at the Australian Antarctic Division where they were housed in purpose-built recirculating aquariums at 6 °C prior to being used in tests. All tests using O. ohlini, T. angulatus, P. macquariensis, and A. directa were done at the Australian Antarctic Division, whereas some tests with Harpacticus sp. and all tests with G. trapesina were done at Macquarie Island. For tests done at the Macquarie Island laboratory, invertebrates were acclimated to laboratory conditions for 2 d.

Test procedures

Each test involved exposure to copper, zinc, or cadmium under a static nonrenewal test regime over 14 d. Tests were done in lidded plastic vials of varying sizes, selected to suit the size and number of individuals in the test (Table 1). All experimental vials and glassware were acid-washed with 10% nitric acid and triplicate rinsed with Milli-Q water before use. Five metal concentrations plus a control were used for each test, and tests were replicated where possible. Concentrations in replicate tests were modified as sensitivity data were accrued from each additional test. Tests were conducted in controlled temperature cabinets set at 6 °C at a light intensity of 2360 lux under a 16:8-h light:dark regime in summer and 16:8-h light:dark regime for tests for the rest of the year. Temperatures within cabinets were monitored throughout the test using Thermochron iButton data loggers.

| Species (cat. no.)a | Vial size (mL) | Volume of test solution (mL) | No. of replicate vials per concentration | No. of individuals per vial | Life history stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harpacticus sp. (G6504) | 70 | 50 | 5 | 10 | Adult |

| Tigriopus angulatus | 70 | 50 | 5 | 10 | Adult |

| Gaimardia trapesina (E31093) | 120 | 100 | 5 | 10 | Adult |

| Obrimoposthia ohlini | 120 | 100 | 5 | 10 | Adult |

| Pseudopsolus macquariensis | 70 | 50 | 4–5 | 6–8 | Juvenile |

| Anasterias directa | 120 | 100 | 4–5 | 6–8 | Juvenile |

- a Voucher specimens of Harpacticus sp. and G. trapesina are held at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

Metal test solutions in filtered (0.45 μm) seawater were prepared 24 h prior to the addition of animals, using 500 μg/L CuSO4, 500 μg/L ZnCl2, and 500 μg/L Cd SO4 Milli-Q stock solutions. Water quality parameters were measured using a TPS 90-FL multimeter at the start (day 0) and end (day 14) of tests. Dissolved oxygen was generally >80% saturation, salinity was 33 ppt to 35 ppt, and pH was approximately 8.1 to 8.3 at the start of tests. Samples of test solutions were taken at 0 d and 14 d for analysis of metal concentration. Samples were filtered through a 0.45-μm Minisart syringe filter and acidified with 1% ultrapure nitric acid prior to analysis via ICP-OES. Measured concentrations at day 0 were on average 95% of the targeted nominal concentrations. Measured concentrations at 0 d and 14 d were averaged to estimate exposure concentrations that were used in statistical analyses (Supplemental Data, Table S1). The average percentage of loss of metals from test solutions over the 14-d test period was calculated for each concentration in each test.

Vials were checked daily, and survival was recorded on days 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, and 14. Individuals of Harpacticus sp. and T. angulatus were considered dead when urosomes were perpendicular to prosomes (as has been used as an endpoint in previous studies with copepods 12). Bivalves, G. trapesina, were considered dead when adductor muscles no longer held shells closed. Flatworms, O. ohlini, were considered dead when they were no longer active and were covered in mucus, and individuals of P. macquariensis and A. directa were considered dead when tube feet were no longer moving. All dead individuals were removed from test vials when observed.

Data analysis

Maximum likelihood probit or trimmed Spearman–Karber models were used for each test to estimate the concentration that caused 50% mortality (LC50) after 4 d, 7 d, 10 d, and 14 d of exposure. No-observed-effect concentrations (NOECs) were determined using Steel's many-one rank or Bonferroni's t hypothesis tests. All estimates were determined using ToxCalc (Ver 5.0, Tidepool Scientific Software).

RESULTS

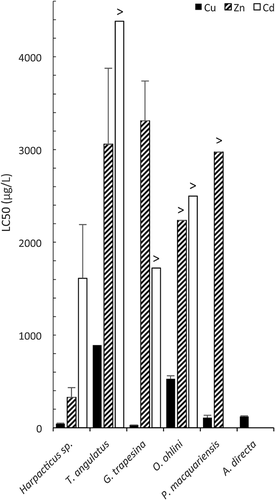

Copper was the most toxic metal to all species tested; sensitivity to metals differed substantially between species (Figure 3 and Table 2). A relative metal toxicity pattern of Cu >> Zn ≥ Cd was found for all species. For both copepods, zinc was more toxic than cadmium (Figure 3 and Table 2). Although this trend was reversed for the bivalve, G. trapesina, differences between metal toxicity were less pronounced by 10 d (Table 2). There was no toxic effect of zinc on the flatworm O. ohlini or sea cucumber P. macquariensis, or of cadmium on O. ohlini, at any of the concentrations tested (Table 2). The bivalve G. trapesina and the copepod Harpacticus sp. were the most sensitive species, particularly to copper, whereas the copepod T. angulatus was highly tolerant of all metals (Figure 3 and Table 2). The response of individuals of all taxa to copper was relatively consistent between tests, but response was more variable for cadmium and zinc, as indicated by the wider fiducial limits for these metals (Supplemental Data, Table S2).

| Day 7 | Day 10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | No. of tests | Range | LC50 mean ±SE | Range | LC50 mean ±SE |

| Copepod Harpacticus sp. | |||||

| Copper (μg/L) | 4 (3) | 35 – 62 | 42 ± 6 | 14 – 25b | 21 ± 4 |

| Zinc (μg/L) | 3 (1) | 133 – 481 | 288 ± 103 | 63b | |

| Cadmium (μg/L) | 3 (0) | 882 – 2758 | 1428 ± 580 | NDb | |

| Copepod Tigriopus angulatus | |||||

| Copper (μg/L) | 1 | 1560 | 892 | ||

| Zinc (μg/L) | 2 | 2238 – 3876 | 2945 ± 819 | 2132 – 2335 | 2231 ± 102 |

| Cadmium (μg/L) | 1 | >4383 | >4383 | ||

| Bivalve Gaimardia trapesina | |||||

| Copper (μg/L) | 2 | 28 – 32 | 30 ± 2 | 13 – 26 | 18 ± 7 |

| Zinc (μg/L) | 2 | 2882 – 3740c | 3283 ± 429 | 2767 – 3000 | 2881 ± 117 |

| Cadmium (μg/L) | 1 | >1722 | 2090c | ||

| Flatworm Obrimoposthin ohlini | |||||

| Copper (μg/L) | 2 | 498 – 560 | 528 ± 31 | 395 – 466 | 429 ± 36 |

| Zinc (μg/L) | 1 | >2238 | >2238 | ||

| Cadmium (μg/L) | 1 | >2498 | >2498 | ||

| Sea cucumber Pseudopsolus macquariensis | |||||

| Copper (μg/L) | 2 | 85 – 134 | 107 ± 25 | 65 – 81 | 73 ± 8 |

| Zinc (μg/L) | 1 | >2973 | >2973 | ||

| Seastar Anasterias directa | |||||

| Copper (μg/L) | 2 | 115 – 127 | 121 ± 6 | 54 – 77 | 64 ± 12 |

- a A “greater than” symbol (>) before an estimate indicates the highest concentration tested and no response. Estimates of LC50 (± 95% fiducial limits) for each test are provided in the Supplemental Data, Table S2.

- b Tests were terminated by day 10 because of high mortality (>60%); numbers in brackets under No. of tests column indicate number of tests for 10-d estimates.

- c Value is just outside of the range of concentrations tested, indicating lower confidence with estimate.

A minimum exposure duration of 7 d was required to elicit a response in most species, particularly for tests with zinc and cadmium (Supplemental Data, Figure S1). Estimates of LC50 could not be determined for most tests at 1 d, 2 d, or 4 d, because of insufficient response at the concentrations tested. Control survival was generally 100% in all tests until 10 d, when it then decreased to 80% to 95% by 14 d, with the exception of Harpacticus sp., in which control survival was particularly low (at ∼60%) in some tests by 10 d (Supplemental Data, Figure S1). Hence, only 7-d and 10-d estimates are reported (Table 2). Water quality parameters remained relatively stable and within acceptable limits throughout most tests up to 14 d (temperature, 6 ±1 °C; salinity, 33–35 ppt; dissolved oxygen, 80–100% saturation; pH, 7.6–8.2). Although not reflected in control survival (which remained at 96–100%), the highest water quality decline was for G. trapesina, with pH dropping to approximately 7.0 by 14 d. Loss of metals, either to test biota or to the walls of experimental vials, over the 14-d exposure period was minimal for both zinc and cadmium but higher for copper (Table 3).

| Average loss of metal from test solutions (% ±1 SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Copper | Zinc | Cadmium |

| Copepod Harpacticus sp. | 26 ± 7 | 4 ± 3 | 1 ± 1 |

| Copepod Tigriopus angulatus | 14 ± 7 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 |

| Bivalve Gaimardia trapesina | 38 ± 4 | 7 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

| Flatworm Obrimoposthia ohlini | 13 ± 2 | 8 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 |

| Sea cucumber Pseudopsolus macquariensis | 27 ± 6 | 3 ± 0 | NT |

| Sea star Anasterias directa | 20 ± 2 | NT | NT |

- SD = standard deviation; NT = tests not conducted.

DISCUSSION

Copper is one of the most toxic metals in marine environments 10, 13, 14; all taxa in the present study were highly sensitive to copper, compared with zinc or cadmium. The relative metal toxicity pattern found in the present study (Cu >> Zn ≥ Cd) was similar to findings for an early life-history stage of the Antarctic echinoid Sterechinus neumayeri 7 and a tropical copepod Tigriopus japonicus 15. In contrast, cadmium has been found to be considerably more toxic than zinc for both the Antarctic amphipods Paramoera walkeri and Orchomenella pinguides 8, as well as the tropical gastropod, Morula granulata 16.

The large variation in species sensitivities to metals in the present study may be in part because of their position on the rocky shore and the environmental conditions they are therefore exposed to. The most copper-tolerant species (T. angulatus and O. ohlini) occur high on the intertidal zone, where they are frequently exposed to significant abiotic stress (Figure 2). Correspondingly, the most copper-sensitive species (Harpacticus sp. and G. trapesina) occur in the subtidal zone under less variable or extreme conditions, where exposure to natural stress may be expected to be low (Figure 2). Similar patterns have been observed between closely related Siphonaria limpet species from South Africa, where species on the upper shore were the most tolerant of copper; it is thought that exposure to natural stress likely provides an adaptation for tolerance of copper contamination 17. A similar pattern was observed for Patella spp. from the Mediterranean, where the effects of copper on cardiac activity differed depending on species distribution in zones on the rocky shore 18.

Two taxa groups in the present study, the copepods and the echinoderms, provide useful comparisons in sensitivity between taxa occurring at different zones in the subantarctic shoreline. Although 2 copepods occupy different habitat zones, and are thus exposed to different levels of natural stress, the 2 echinoderms occupy similar habitats. The copepods are within the same family (Harpacticidae), yet T. angulatus was considerably more tolerant than Harpacticus sp. to all metals (Table 2 and Figure 3). Insensitivity to contaminants is a common finding for members of the genus Tigriopus in most regions 12, 19. Furthermore, all Tigriopus species are found in splash pools of high abiotic variability (12, 20, 21; personal observation). To cope with the extreme abiotic changes in these environments, Tigriopus species have been reported to enter a so-called dormant phase, with reduced metabolism, until conditions improve 20, which they may also adopt when exposed to contamination 12. Contrary to the copepods, both echinoderms in the present study (sea cucumber P. macquariensis and sea star A. directa), occur only on the lower shore and exhibit similar sensitivities to copper (Table 2 and Figure 3).

As recommended in previous studies with species from high latitudes 7-9, 22, a longer exposure time was required to elicit a response in the test species from Macquarie Island. The exposure duration used in tests in the present study was increased from the conventional 24 h to 96 h, to 7 h to 14 d to enable more realistic comparisons of sensitivities between biota from different regions. This increase is biologically consistent with the longer life-history stages and slow metabolism of Antarctic species 10. The sensitivity of subantarctic species increased with exposure time, and a minimum of 7 d was required for most species to respond to metals. This finding is consistent with previous studies with Antarctic copepods, in which 7-d exposure durations were recommended 9, and for other Antarctic invertebrates, in which exposure times of up to 30 d were required to elicit a response 8.

Although a test duration of 7 d or 10 d was selected as appropriate in the present study, a longer exposure time with these subantarctic species could result in higher sensitivities to copper and might also indicate some sensitivity to zinc or cadmium for those taxa that did not respond after 14 d of exposure. However, using a static test method, exposure duration could not reliably be increased to more than 10 d, as control mortality started to occur at this time for Harpacticus sp. This is likely because of a decline in water quality and lack of food. A reduction in water quality was particularly apparent for the bivalve G. trapesina by 14 d. For future studies with this species, we therefore suggest that a static renewal regime be undertaken, with water changes every 7 d, and, if required, food provided to test organisms during the experiment, to determine responses over a longer exposure period.

A further consideration is the ecological relevance of the exposure time selected for tests. In contrast to Antarctic species, longer exposure times in the subantarctic may not be as relevant to real-life exposure scenarios. In the Antarctic, the presence of sea ice results in low-energy environments, and thus slower removal of contaminants, whereas many subantarctic marine areas are high-energy environments, and contamination would likely be removed at a faster rate.

The bivalve G. trapesina was the most sensitive species to copper in the present study (Table 2 and Figure 3). Bivalves are generally sensitive to metal contamination and often accumulate high concentrations of metals 23, 24. Although accumulation was not determined in the present study, based on the loss of copper from test solutions, it appeared that G. trapesina was the largest accumulator of copper of the species tested. Copper concentrations in test solutions were reduced by up to 38% over the experimental period in tests with bivalves, compared with smaller losses in tests with other species conducted under similar test conditions (Table 3). As deposit or suspension feeders, bivalves take up metals in the dissolved form as well as particles collected during feeding 25. Their ability to accumulate metals has led to the regular use of bivalves in biomonitoring programs worldwide 25. Previous studies with temperate bivalves have found a wide range in sensitivities to copper; Mya arenaria: 7-d Cu LC50, 35 μg/L 26; Tellina deltoidalis: 8-d Cu LC50, 31 μg/L 24; Soletellina alba: 4-d Cu LC50, 120 μg/L; and Mysella anomala: 4-d Cu LC50, 1500 μg/L 27. The subantarctic G. trapesina showed similarly high sensitivity to copper as the most sensitive temperate species 24, 26.

Copepods are commonly used as toxicity test species globally, providing datasets with which to compare regional sensitivities to copper. Although the sensitivities of temperate copepods are variable, high-latitude copepods appear to be highly sensitive to copper (Figure 4). Three Antarctic species are highly sensitive in comparison with most other species 9, whereas 1 of the 2 subantarctic species from the present study (Harpacticus sp.) exhibits similarly high sensitivity. In contrast, the subantarctic T. angulatus is highly tolerant and of similar sensitivity to tropical and temperate Tigriopus species 12, 15, 28, 29. Because all Tigriopus species reside in splash zones and encounter harsh extremes worldwide, it may be that intertidal distribution has more of an impact on their sensitivities than regional distribution. The other main exception to the pattern in latitudinal sensitivity is the tropical pelagic copepod Acartia sinjiensis, (48-h Cu LC50, 33 μg/L 30). Gissi et al. 30 suggested that sensitivity may be higher at low latitudes; however, with very few low-latitude studies, this is difficult to confirm. Previous studies with other taxa 7, 10 affirm this finding of increased copper sensitivity of copepods at higher latitudes.

Along with being the first study to report metal toxicity to subantarctic marine invertebrates, the present study is also one of the few on juvenile echinoderm sensitivity. Most other studies on echinoderms focus on fertilization, embryonic, or larval stages. In addition, few data are available on the sensitivity of saltwater flatworms to metals 31, with the exception of a highly sensitive temperate polyclad flatworm with a 4-d LC50 of 14 μg/L to 17 μg/L 32.

Based on the sensitivities of the species in the present study, it appears unlikely that water quality guidelines developed in temperate areas will be suitable for subantarctic areas. Like Antarctic biota, longer test durations with subantarctic biota were required to deliver valid and robust results. We highlight the importance of testing a wide diversity of species when attempting to develop guidelines for a particular region, as the variation in sensitivities between taxa may be considerable and may be related to the likelihood of exposure to natural stressors. The present study provides the first data on metal toxicity to subantarctic marine invertebrates and contributes significantly as a first step toward understanding the relative sensitivity of subantarctic marine biota to metals. Further research with local biota is required to provide better estimates of the sensitivity of taxa in this region to contamination.

Supplemental Data

The Supplemental Data are available on the Wiley Online Library at DOI: 10.1002/etc.3382.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank B. Sfiligoj in particular for assistance with field and experimental work, along with the expeditioners to Macquarie Island in 2013/2014 for support of this project. Thanks also to A. Cooper for assistance with ICP-OES data and general help throughout the project and to J. Wasley for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Permits for collections were granted by the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania. This research was supported through an Australian Antarctic Science Grant (AAS 4100) awarded to C. King and through an Australian Postgraduate Award to J. Holan.

Data availability

The metadata associated with this research, “Holan J, King C, Davis AR. 2015. Toxicity of copper, cadmium and zinc to Macquarie Island marine invertebrates. Australian Antarctic Data Centre. DOI: 10.4225/15/56369D520A118” is publicly available on the Australian Antarctic Data Center website. These data can also be available on request ([email protected]).