Short-term sick leave due to epilepsy in the Swedish Prospective Regional Epilepsy Database and Biobank for Individualized Clinical Treatment (PREDICT)

Abstract

Objective

Epilepsy is associated with low socioeconomic standing and increases the risk of sick leave. Longer periods resulting in benefit payments are captured by administrative data, but the disease also entails a risk of repeated short sick leave periods, which have so far not been studied or quantified. The aim of this study was to describe the frequency of short sick leave in persons with epilepsy (PWE) and the characteristics of these PWE.

Methods

A prospective multicenter study, Prospective Regional Epilepsy Database and Biobank for Individualized Clinical Treatment (PREDICT) project, based on medical records and yearly self-report questionnaires in 2020–2023. PWE from five neurology departments who were working, studying, or applying for work were included, and they reported the number of sick leave days the past year in the questionnaires. Socioeconomic data was retrieved from Statistics Sweden. Demographic and clinical factors were compared by chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results

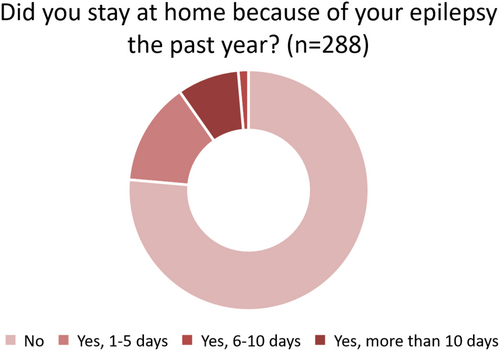

Of the 288 included PWE, 76.4% (n = 220) stated not having stayed at home due to their epilepsy, 13.9% (n = 40) replied 1–5 days, 1.4% (n = 4) 6–10 days, and 8.3% (n = 27) >10 days. More recently diagnosed PWE reported more sick leave days. Short-term sick leave was more prevalent in those with seizures, with medication side effects, and in those with polytherapy. Demographic and socioeconomic factors did not differ between those with or without sick leave days. In the 184 participants who had replied to the questionnaire at the 1 and/or 2 years' follow-up, the distribution did not differ from the baseline report.

Significance

Most PWE do not have short-term sick leave. Short-term sick leave was mainly seen in those with more difficult-to-treat or newly diagnosed epilepsy. Future studies should address if interventions like information about high-risk periods to patients and employers can improve psychosocial outcomes.

Plain Language Summary

Epilepsy can impact work ability, potentially leading to longer sick leaves or disability pensions, but shorter absences are less studied and are not included in the national registries in Sweden. This study explores shorter work absences in epilepsy patients attending neurology clinics in western Sweden. A quarter of patients reported missed workdays, but 68% had no sick leave recorded in national registries. Those with poorly controlled or newly diagnosed epilepsy were more likely to take sick leave, offering insights for patients, healthcare providers, and employers about managing epilepsy in the workplace.

Key points

- Epilepsy entails a risk of short-term sick leave periods, which are not captured by Swedish national registries.

- The study included 288 working or studying PWE in routine neurological care, from the regional prospective PREDICT study.

- 23.6% reported short-term sick leave due to epilepsy, and 68% of them did not have any absences from work recorded in the national registry.

- Demographic or socioeconomic differences were not found to be relevant for reports of absence from work.

- PWE with seizures, polypharmacy, ASM side effects, or a more recent epilepsy diagnosis had more sick leave.

1 BACKGROUND

Epilepsy can negatively impact the ability to work and entails higher socioeconomic costs than in controls.1, 2 Contributing to the socioeconomic burden of epilepsy, the condition is associated with lower employment rates, not only due to direct disease-related causes such as seizure severity and polypharmacy, but also interacting problems including stigma and psychosocial factors.3-6 In employed persons, epilepsy involves a risk of needing an early disability pension, with a higher risk in older persons, those with previous longer sick leave periods, and those with psychiatric comorbidities.1, 7

The nature of epilepsy entails a high risk also of short absences from work due to seizures. Qualitative research often identifies missing work as a factor of concern for patients,8-10 but quantitative studies are relatively rare. A recent Spanish register-based study on the clinical and economic implications of epilepsy reported sick leave in 20.2% of 5006 persons with epilepsy (PWE), with a range from 19.1% to 25.6% between the first and the fourth or more treatment lines.11 The number of sick leave days was one of the outcome measures in another study by Kleinman et al., designed to compare the effects of gabapentin or pregabalin treatment for focal onset epilepsy. That study found an adjusted mean number of days of 10.8 in a 6-month follow-up in 9 of 107 gabapentin-treated patients compared to 1.5 days in 10 of 66 pregabalin-treated patients.12 Brook et al.13 found that also the spouses of patients with focal onset epilepsy needed sick leave days due to their spouses' disease: 2.4 days per year when the person with epilepsy was on monotherapy and 4.4 days per year if that person was prescribed adjunctive therapy.

In Sweden, the national Social Insurance Agency provides publicly funded benefits for salary earners in need of sick leave of above 14 days duration. Shorter periods of sick leave are reimbursed by the employer, and there is no universal register that captures the extent of these absences from work. The extent of short-term sick leave due to epilepsy in Sweden is unknown.

The aim of this study is to describe the extent of short-term sick leave in working and studying PWE in a regional prospective multicenter study and to identify characteristics of these PWE.

2 METHODS

Data were collected in the Prospective Regional Epilepsy Database and Biobank for Individualized Clinical Treatment (PREDICT) project (clinicaltrials.org identifier: NCT04559919). PREDICT is a multicenter prospective cohort study on adult patients aged ≥18 years, with an unprovoked seizure or with epilepsy, residing in Västra Götaland County in Sweden. Patients were included by physicians at routine clinical visits at five public neurological clinics. The study and its catchment area were described in a previous study.14

Data were retrieved from medical files and from a self-report questionnaire that patients filled in at the time of inclusion in the study (File S1). Information about their current occupation was retrieved from that questionnaire, from two questions: “Do you have an employment? If so, what (free text)” and “Do you study? If so, what (free text).” Further, data about short-term sick leave was retrieved from the questionnaire, from a multiple-choice question: “Did you during the past year stay at home from work/studies or refrain from applying from work, because of your epilepsy?—No; Yes, 1–5 days; Yes, 6–10 days; Yes, more than 10 days.”

The prevalence of side effects was assessed in the questionnaire, where participants were asked to indicate whether they have side effects or not, followed by an open question on what type of side effects they experience (File S1).

The participants are being followed longitudinally and are being asked to complete the same self-report questionnaire yearly.

The study start date for the PREDICT study was on December 15, 2020, and data for all so far included PWE fulfilling the diagnostic criteria according to the current International League Against Epilepsy definition (epilepsy with seizure in the last 10 or antiepileptic drug treatment in the last 5 years)15 were extracted on September 4, 2023 for inclusion in the present study. All participants were aged 18 years or above, and all received written study information, available in Swedish, English, and Arabic, and gave written consent to be included in the study. Exclusion criteria were the inability to understand the study information and give one's consent, or a life expectancy of less than 2 years. Specific inclusion criteria for the present study were patients who were currently working or applying for work, and students.

Data for responses in the yearly self-report questionnaires after 1 and 2 years in the study was retrieved on January 4, 2024.

Information on socioeconomic factors, including income, main source of income, educational level, employment status, number of persons in a household, and (when applicable) year of immigration, was collected from the Longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labor market studies (Statistics Sweden, LISA), for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022. Statistics Sweden provided LISA register data for 286 persons. Data from the LISA register was also used as support for the determination of which participants to include in the study in cases where responses from the questionnaires contained incomplete information on participants' current occupation.

Income level was reported in the definition of the Public Health Agency in Sweden. This definition is based on the income of the whole population 20–64 years of age. Thresholds for “low” and “high” income are set for each year to the income level of the lowest 20% and of the highest 20% of the population, respectively. For 2020 those thresholds were ≤152 590 and ≥497 207 SEK; for 2021: ≤162 631 and ≥519 137 SEK; and for 2022: ≤178 330 and ≥540 177 SEK.

The second included economic variable from the LISA register is a household income calculated by Statistics Sweden, where the total of incomes are divided by the consumption weight of all individuals in a household, assuming equal economical standards for each individual, here referred to as “household weighted income.”

The number of sick leave days in the LISA register represents periods above 14 days, and is the sum of sick leave days per calendar year, for any cause. The number represents the sum of whole days, meaning, for example, that a person with 50% sick leave, working 4 instead of 8 hours per day during 1 year, will have 366/2 = 183 sick leave days registered. To capture the period closest to the date of inclusion in the study, for those included until June 2021, the number of sick leave days in LISA for 2020 was reported. For those included July 2021 to June 2022, the number of sick leave days in LISA 2021 was reported, and for those included in July 2022 or later, the number of sick leave days in LISA 2022 was reported.

2.1 Statistics

Descriptive statistics are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or number (%). To analyze group differences, we used Mann–Whitney's test for continuous data, and Fisher's exact test or the chi-squared test to compare proportions. Logistic regression was used to explore which of the significant factors in univariate analyses had the strongest association with having stayed at home due to epilepsy the past year. For comparisons between responses to the multiple-choice question about the number of sick leave days due to epilepsy the past year, at baseline compared to after 1 and 2 years, the Friedman test was used. All tests were two-sided and considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS v.29 for Windows.

2.2 Ethical approval

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the study (approval no 2020-00853 with addition 2021-00257) and written consent was obtained from all participants. We confirm that we have read the journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

3 RESULTS

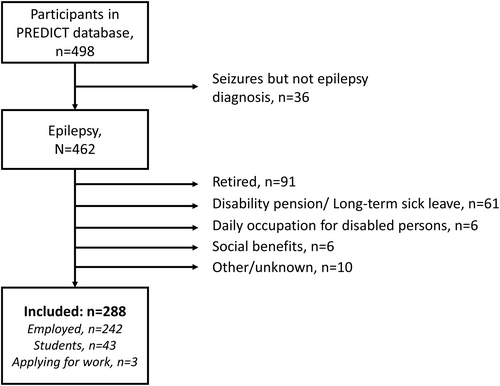

Until September 4, 2023, 462 persons with epilepsy had been included in PREDICT; 91 were retired, 61 had disability pensions or were on long-term sick leave, 6 participated in daily activities for functionally disabled persons, 6 were receiving social benefits, and in 10 cases the current occupation could not be discerned from available data. The remaining 288 persons constituted the study group; of these, 242 were employed, 43 were students, and 3 were currently applying for work (flowchart, Figure 1). Demographic and clinical data for the study group are shown in Table 1.

| No. of cases with data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 288 | 37.0 ± 13.4 |

| Sex, F/M, n/n (%/%) | 288 | 163/125 (56.6/43.4) |

| Epilepsy type, n (%) | 274 | |

| Focal | 159 (58.0) | |

| Generalized | 61 (22.3) | |

| Unknown | 54 (19.7) | |

| Hospital, n (%) | 288 | |

| Sahlgrenska University Hospital | 235 (81.6) | |

| Södra Älvsborg Hospital | 10 (3.5) | |

| Frölunda Specialist Hospital | 12 (4.2) | |

| Northern Älvsborg County Hospital | 7 (2.4) | |

| Angered Hospital | 24 (8.3) | |

| Single household, n (%) | 286 | 66 (23.1) |

| Driving license, n (%) | 236 | 154 (65.2) |

| Immigranta, n (%) | 286 | 53 (18.5) |

| Duration of epilepsy, years, median [IQR] | 270 | 11.7 [6.0–22.2] |

| Duration of epilepsy, n (%) | 270 | |

| <2 years | 27 (10.0) | |

| 2–5 years | 39 (14.4) | |

| 6–10 years | 62 (23.0) | |

| >10 years | 142 (52.6) | |

| Seizure/s occurred past 2 months, n (%) | 275 | 94 (34.2) |

| Seizure/s occurred past year, n (%) | 283 | 131 (46.3) |

| Loss of consciousness past year, n (%) | 187 | 91 (48.7) |

| Number of ASM at inclusion, n (%) | 288 | |

| None | 14 (4.9) | |

| One | 183 (63.5) | |

| Two to four | 91 (31.6) | |

| Forgot ASM doses past year, n (%) | 285 | |

| No | 93 (32.6) | |

| Once | 45 (15.1) | |

| 2–10 times | 115 (40.4) | |

| >10 times | 20 (7.0) | |

| No ASM at study inclusion | 14 (4.9) | |

| Side effects, n (%) | 275 | |

| Yes | 106 (38.5) | |

| No | 155 (56.4) | |

| No ASM at study inclusion | 14 (5.1) | |

| Education, n (%) | 281 | |

| School ≤9 years | 28 (10.0) | |

| High school ≤3 years | 114 (40.6) | |

| University | 139 (49.5) | |

| Income (100 SEK), median [IQR] | 286 | 3151 [1355–4219] |

| Household weighted income (100 SEK), median [IQR] | 286 | 2951 [2308–3673] |

| Number of sick leave days in LISA, n (%) | 286 | |

| 0 | 231 (80.8) | |

| 1–30 | 21 (7.3) | |

| 31–150 | 23 (8.0) | |

| 151–258 | 11 (3.8) |

- Abbreviations: ASM, anti-seizure medication; F, female; IQR, interquartile range; LISA, longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labor market studies; M, male; SD, standard deviation; SEK, Swedish krona.

- a Born outside Sweden.

Of the 288 patients, 76.4% (n = 220) stated not having stayed at home due to their epilepsy, 13.9% (n = 40) replied 1–5 days, 1.4% (n = 4) 6–10 days, and 8.3% (n = 24) >10 days (Figure 2).

Comparisons of demographic and clinical data between patients without (n = 220) or with short-term sick leave (n = 68) are shown in Table 2. The age and sex distribution did not differ between the groups, nor did the type of epilepsy. There were significantly more patients with seizures in the past year in the group who had sick leave days.

| No sick leave | Sick leave | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 220 | n = 68 | ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 37 ± 14 | 35 ± 13 | 0.40 |

| Sex, F/M, n/n (%/%) | 126/94 (57.3/43.7) | 37/31 (54.4/45.6) | 0.68 |

| Epilepsy type, n (%) | |||

| Focal | 123 (58.6) | 36 (56.3) | 0.88 |

| Generalized | 47 (22.4) | 14 (21.9) | |

| Unknown | 40 (19.0) | 14 (21.9) | |

| Hospital, tertiary, n (%) | 174 (79.1) | 61 (89.7) | 0.050 |

| Single household, n (%) | 52 (23.9) | 14 (20.6) | 0.63 |

| Driving license, n (%) | 121 (67.2) | 33 (58.9) | 0.27 |

| Immigranta, n (%) | 40 (18.3) | 13 (19.1) | 0.86 |

| Duration of epilepsy, years, median [IQR] | 12.3 [6.9–22.9] | 8.9 [3.4–19.8] | 0.053 |

| Duration of epilepsy, n (%) | |||

| <2 years | 12 (5.8) | 15 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| 2–5 years | 34 (16.4) | 5 (7.9) | |

| 6–10 years | 48 (23.2) | 14 (22.2) | |

| >10 years | 113 (54.6) | 29 (46.0) | |

| Seizure occurred past 2 months, n (%) | 53 (25.2) | 41 (63.1) | <0.001 |

| Seizure occurred past year, n (%) | 74 (34.3) | 57 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| Polytherapy, n (%) | 59 (26.8) | 32 (47.1) | 0.003 |

| Forgot ASM doses past year, n (%) | 108 (51.4) | 26 (42.6) | 0.25 |

| Side effects, n (%) | 78 (37.3) | 40 (61.5) | <0.001 |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| School ≤9 years | 18 (8.4) | 10 (14.9) | 0.13 |

| High school ≤3 years | 84 (39.3) | 30 (44.8) | |

| University | 112 (52.3) | 27 (40.3) | |

| Income level, n (%) | |||

| Low | 63 (28.9) | 17 (25.0) | 0.49 |

| Medium | 131 (60.1) | 46 (67.6) | |

| High | 24 (11.0) | 5 (7.4) | |

| Household weighted income (100 SEK), quartiles | |||

| <2308 | 55 (25.2) | 16 (23.5) | 0.94 |

| 2308–2951 | 53 (24.3) | 19 (27.9) | |

| 2952–3673 | 55 (25.2) | 17 (25.0) | |

| >3673 | 55 (25.2) | 16 (23.5) | |

- Abbreviations: ASM, anti-seizure medication; F, female; IQR, interquartile range; LISA, longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labor market studies; M, male; SD, standard deviation; SEK, Swedish krona.

- a Born outside Sweden.

Of the 131 participants who reported seizures in the past year, 128 replied to the question about whether any of those seizures entailed loss of consciousness (yes/no). Sixty-eight % (n = 87) replied “yes,” 32% (n = 41) “no.” In these 128 participants with seizures the past year, having stayed at home was more common in those with loss of consciousness, but without reaching significance (76.4% vs. 61.6%, Chi2 test: p = 0.077).

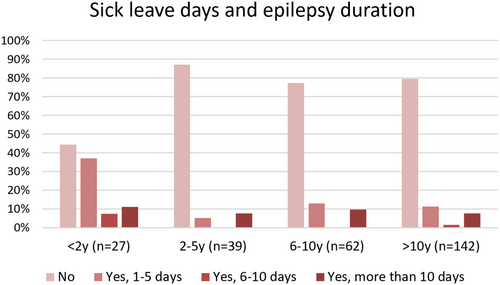

Sick leave due to epilepsy was more common during the first 2 years after diagnosis (Table 2, Figure 3, Chi2-test p < 0.001). Patients with polytherapy (two to four anti-seizure medications [ASM]) were over-represented in the group with sick leave days. There was a trend toward more sick leave days in patients at the tertiary centre (89.7% vs. 79.1% in the smaller hospitals, p = 0.050).

The prevalence of driving license holders did not differ between the groups, nor did the prevalence of persons living in single households. Socioeconomic variables (education level, income level, and household weighted income) did not differ between PWE with or without self-reported sick leave due to epilepsy. Immigrants were equally represented in both groups.

Reporting seizures during the past year, side effects and ASM polytherapy were each significantly associated with sick leaves when analyzed separately. There was covariance between these factors, and logistic regression was used to identify the most important factor. In univariate analyses, using “stayed at home the past year” as the dependent variable, “seizures past year” (OR 10.94; 95% CI 5.28–22.66, p < 0.001), “side effects” (OR 2.69; 95% CI 1.52–4.77, p < 0.001), and “ASM polytherapy” (OR 2.45; 95% CI 1.39–4.31, p = 0.002) all displayed significant associations. In a multivariate model with these three factors, “seizures past year” and “side effects” remained significant with “seizures past year” as the strongest associated factor, while “ASM polytherapy” was no longer significant (“seizures past year” OR 8.96; 95% CI 4.22–19.04, p < 0.001, “side effects” OR 1.95; 95% CI 1.02–3.72, p = 0.042, and “ASM polytherapy” OR 1.24; 95% CI 0.64–2.40, p = 0.53).

3.1 Follow-up after 1 and 2 years

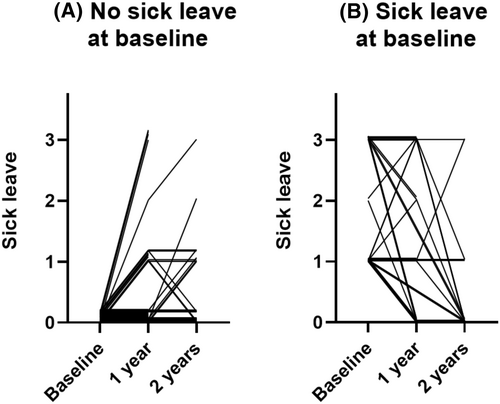

One-hundred and eighty-four participants had replied to the question about sick leave more than once. At the 1-year follow-up, three participants (born 1957 or earlier) reported now being retired from work, and their responses were not included in the follow-up. Information about sick leave was reported by 56.6% (n = 165) at the 1-year follow-up, and 29.5% (n = 85) at the 2 years' follow-up. Of the respondents in the one-year follow-up 23.0% (38/165) reported sick leave the past year, and in the two-years follow-up 18.8% (16/85) reported sick leave. There was no significant difference between the responses at baseline and follow-up after 1 and 2 years (p = 0.79). The trajectories of the responses for participants at 1 and 2 years' follow-up, with and without sick leave at baseline, are shown in Figure 4.

3.2 National register data

We finally analyzed to what extent persons with reported short-term sick leave also had long-term sick leave in national registers. In the Statistics Sweden LISA register, which contains sick leave periods longer than 14 days, 19.2% (n = 55) had all-cause sick leave. Of these, 21 (7.3% of the total cohort) had <30 days, 23 (8.0%) had 31–150 days, and 11 (3.8%) had 151–258 days of all-cause sick leave days. Forty-six participants who reported sick leave in the questionnaires did not have any sick leave days registered in the national register, constituting 68% of the 68 participants with self-reported sick leave (Table 3).

| Number of all-cause sick leave days | Stayed at home due to epilepsy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes, 1–5 days | Yes, 6–10 days | Yes, more than 10 days | Total | |

| 0 | 185 | 34 | 1 | 11 | 231 |

| 1–30 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 21 |

| 31–150 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 23 |

| 151–258 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 |

| Total | 218 | 40 | 4 | 24 | 286 |

- Note: The calendar year closest to the time point of inclusion is presented. The self-report refers to sick leave days due to epilepsy only, and the time period is the past year at the time of inclusion.

4 DISCUSSION

Short-term sick leave due to their epilepsy was reported by 23.6% of PWE in routine neurological care. For 68% of individuals reporting sick leave in our questionnaire, there was no long-term sick leave registered in the national register. This suggests that short-term sick leave impacts a considerable proportion of persons with epilepsy and that work absence due to epilepsy may be underestimated in studies relying on administrative data.

We also identified clinical characteristics associated with short-term sick leave. PWE having had their diagnosis for less than 2 years were more likely to have short-term sick leave compared to those with an epilepsy diagnosis for more than 2 years. We interpret this as a result of treatment, as 85.2% (n = 23) of the 27 participants with less than 2 years since epilepsy diagnosis reported seizures the past year, compared to 40.8% (n = 97) of 238 of those with an epilepsy diagnosis for more than 2 years. The onset of epilepsy is a psychosocially challenging period according to qualitative research, and other contributing factors may be the burden of a new diagnosis as well as stigma.16

The proportion in our study was higher than in the Spanish study by Toledano et al., where sick leave was reported in 20.2% of PWE. Comparing sick leave figures between countries involves a possible bias due to different social security systems. Participants on polytherapy also reported sick leave to a larger extent than those on monotherapy, similar as in the study by Toledano et al.11 reporting more frequent sick leave for each treatment line, and similar to the finding by Brook et al.,13 concerning the spouses of PWE who also had more absence from work if their spouse had more than one ASM. Further, PWE who reported medication side effects were also over-represented among participants with sick leave. It was already known from our earlier study that side effects are associated with polytherapy.17 In the present study group, 56.3% of those with polytherapy reported side effects, compared to 30.3% of those on monotherapy (p < 0.001). In the multivariate model, side effects were a stronger associated factor than ASM polytherapy, and the association with having had seizures the past year greatly exceeded the other factors.

Educational and income levels are lower in PWE than in controls in Sweden, and a more severe epilepsy with hospitalizations is associated with a lower socioeconomic standing (SES).18 However, in the present study, we could not find that any of the included possible markers of SES were associated with the prevalence of short-term sick leave. Possibly, this could be due to the much smaller cohort of PWE in the present study, but also, and probably more importantly, we did not include those who had retired, those with disability pensions or on 100% long-term sick leave, nor those who received social benefits.

Further, a study from the United Kingdom showed higher rates of first fit note receipt for those self-defining to belong to a minority ethnic group, as well as for those with multiple long-term conditions.1 The PREDICT study did not include information about ethnicity, but we could not find any difference in the prevalence of short-term sick leave in participants who had immigrated versus those who were born in Sweden.

Specht et al.7 showed that age > 50 years increases the risk of disability pension. We could not find in the present study that age was a risk factor for short-term sick leave. Risk factors for receiving a disability pension were not studied here, and the follow-up time so far in the PREDICT study is insufficient to elucidate whether short-term sick leave is a risk factor for receiving a disability pension, but longitudinal follow-up for ten years is planned, and that question is a possible topic for future study.

In our cohort of PWE, 19.2% had been reimbursed for sick leave of any cause for periods longer than 14 days. This is approximately twice the proportion of the general population (10.5%); in Sweden, 619 323 persons received sick leave reimbursements from the national Social Insurance Agency for periods above 14 days in 2021,19 and in the same year, the Swedish population aged 20–65 years was 5 898 671 inhabitants.20 Our cohort was selected to capture short-term sick leave: for example, students were included, and those with long-term sick leave or disability pensions were excluded; a similar cohort from the general population is not available. Short-term sick leave statistics for the general population are not as readily available, but during the study period, there were approximately 0.44 cases of short-term sick leave per employee and quarter.21 Our finding that 28% of participants stated short-term sick leave due to epilepsy cannot therefore be easily compared to the general population; the short-term sick leave due to epilepsy may or may not be added to other short-term sick leave. The possible conclusions from our data is instead that short-term sick leave for epilepsy constitutes a substantial proportion of the total sick leave, and that among PWE, the first 2 years seem to carry the greatest risk.

Migraine is another neurological disorder with paroxysmal episodes associated with an increase in short-term sick leave.22-24 In Scandinavian population-based studies of people with migraine, with similar methods of self-reporting sick leave in the past year, sick leave was reported by 43%22 and 59%.23 Our study showed a lower rate of sick leave, but 24% is not insignificant. It is often argued that sick leave represents a major factor of indirect cost for migraine sufferers, and this study suggests that this also holds true for PWE.

PWE with suboptimal seizure control were more likely to have short-term sick leave, which is similar to the increasing prevalence of sick leave with increasing frequency of migraine.23 The burden of sick leave due to migraine was higher for each failed treatment line,24 as in the epilepsy study by Toledano et al.11 as mentioned above, and in parallel with our study. In migraine sufferers, psychiatric and other comorbidities are known to increase the risk of sick leave, but we do not know if this holds true for PWE in our study as we did not assess for psychiatric or other comorbidities. However, Specht et al.7 reported that psychiatric comorbidity was a risk factor for long-term sick leave and disability pension in PWE and Dorrington et al.1 reported that the risk of receiving a fit note receipt was higher in PWE with a comorbidity of depression, indicating that there might be such an increase in risk for short-term sick leave as well.

A major limitation to this study was that the exact total number of sick leave days due to epilepsy and the total number of days due to other causes during the same time period were not accounted for. The only method available to capture short-term sick leave days below 14 days of coherent sick leave is to ask the participants, as no universal register holds that information, and that was done at the time point of inclusion in the study. The risk of a recall bias must also be considered with a time frame of 1 year. We did not have access to the exact dates and causes of sick leave reimbursed by the national Social Insurance Agency for sick leave periods above 14 days, and the data we had access to from the LISA register was per calendar year, which therefore does not match the time period referred to in the questionnaire. We presented the most accurate data available in these circumstances.

Concurrently, the major strength of the study was the use of self-report of the number of days away from work due to epilepsy, in a large well-characterized cohort of PWE in routine neurological care from several centers. As established, this data is not available in any other source of information and has to our knowledge not been captured in any previous Scandinavian study.

There were also minor limitations, including that we did not assess psychiatric or other comorbidities, nor patients' cognitive level, which have been shown in other studies to be of relevance for work capacity in PWE.1, 7 What stood out clearly in our results was that PWE with markers of less well-controlled epilepsy were those who to a larger extent needed to stay at home due to their epilepsy, but the interplay with depression and other comorbidities is unknown.

An important conclusion of this study is that the majority of PWE did not need short or long (>14d) sick leave periods. Short-term sick leave was more common in PWE within 2 years from the diagnosis. This insight is an important message to caregivers to help give support and explain to employers and patients in this phase, avoiding unnecessary longer-term negative consequences in the work life.

5 CONCLUSION

This study shows that short-term sick leave due to epilepsy affects a minority of working PWE, but is reported by almost one fourth seen in routine neurological care in this multicenter study. A substantial proportion of PWE with short-term sick leave have no long-term sick leave. Sick leave was more prevalent in those with newly diagnosed epilepsy, occurrence of seizures, polypharmacy, and side effects, while demographic or socioeconomic variables were not shown to be relevant factors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KA: Supervision of local inclusion, data processing, statistical analyses, interpretation of results, figure design, and draft of the manuscript. DL: Data collection, interpretation of results, and revision of the manuscript. FA: Data collection, interpretation of results, and revision of the manuscript. JZ: Conceptualization of the study, supervision of inclusion and data collection, analysis planning, interpretation of results, figure design, and revision of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was funded by the R&D Department at Angered Hospital, Gothenburg, VGR Regional Grants (VGFOUREG-980937), and the Swedish State through the ALF-Agreement (ALFGBG-965029).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

JZ has received speaker honoraria from UCB and Eisai and has as an employee of Sahlgrenska University Hospital (no personal compensation) been an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Bial, UCB, GW Pharma, SK life science, and Angelini Pharma. FA has received speaker honoraria and consultancy fees from Angelini Pharma. DW and KA disclose no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available upon reasonable request from any qualified investigator.