Interactions between antiseizure medications and foods and drinks: A systematic review

Abstract

Antiseizure medications (ASMs) constitute the principal of treatment for patients with epilepsy, where long-term treatment is usually necessary. The purpose of this systematic review is to provide practical and useful information regarding various aspects of the interactions between ASMs and foods and drinks. MEDLINE and ScienceDirect, from the inception to July 15, 2023, were searched for related publications. In both electronic databases, the following search strategy was applied, and the following keywords were used (in title/abstract): “food OR drink” AND “antiepileptic OR antiseizure.” The primary search yielded 738 studies. After implementing our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we could identify 19 studies on the issue of interest for our endeavor. Four studies were identified in the recheck process and not by the primary search. All studies provided low level of evidence. Interactions between foods and ASMs are a common phenomenon. Many factors may play a role for such an interaction to come to play; these include drug properties, administration route, and administration schedule, among others. Drugs-foods (-drinks) interactions may change the drug exposure or plasma levels of drugs (e.g., grapefruit juice increases carbamazepine concentrations and the bioavailability of cannabidiol is increased 4–5 folds with concomitant intake of fat-rich food); this may require dosage adjustments. Interactions between ASMs and foods and drinks may be important. This should be taken seriously into consideration when consulting patients and their caregivers about ASMs. Future well-designed investigations should explore the specific interactions between foods (and drinks) and ASMs to clarify whether they are clinically important.

Plain Language Summary

Interactions between antiseizure medications and foods and drinks may be important. This should be taken into consideration in patients with epilepsy.

Key points

- Interactions between antiseizure medications and foods are an important issue.

- Grapefruit juice is associated with increased carbamazepine concentrations.

- Patients with epilepsy should be aware of drugs and foods/drinks interactions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy is a common chronic brain disorder; its prevalence is seven patients per 1000 persons and its incidence is 47 patients per 100 000 persons per year in the world.1-3 Antiseizure medications (ASMs) constitute the principal of treatment for patients with epilepsy (PWE). Many PWE have to regularly take their medications (ASMs) for a long period of time.4 Therefore, it is necessary to consider all the details in various aspects of their life in order to make this mandate more tolerable and at the same time more efficient. Both for older and also for more recently approved ASMs, pharmacokinetic challenges are common and they have to be considered in any individual patient; pharmacokinetic interactions, saturation kinetics, and risk of toxicity are some of the important considerations.5, 6 Therapeutic drug monitoring is often implemented to take such factors of variability into account and thus individualize the treatment plans.7, 8

Interactions between drugs and food and drinks may be important; these are often unrecognized issues in routine clinical practice.9, 10 Regular and frequent food and drink consumption is a routine and necessary life activity. Since PWE often have to take their drugs for long periods of time, it is important that patients, their caregivers, and also their treating healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, and pharmacists) have a good knowledge of the significant drug–food (drinks) interactions and other related issues.

The purpose of this systematic review is to provide practical and useful information regarding various aspects of the relationship between ASMs and ordinary foods and drinks (non-alcoholic) in a concise manner. Issues such as weight considerations, bone health, or therapeutic (e.g., ketogenic) diets are beyond the scope of this review and will not be discussed.

2 METHODS

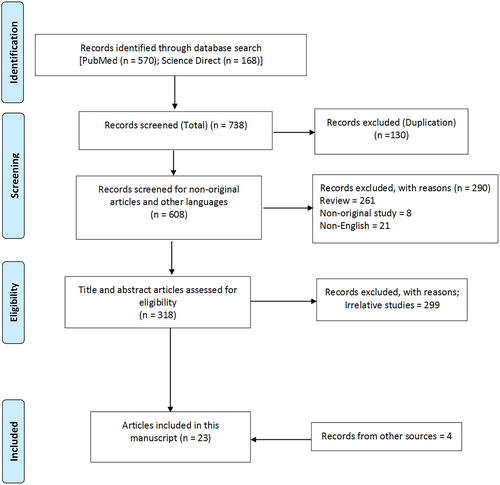

This systematic review was put together according to the instructions of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. This review protocol was not registered. MEDLINE (accessed from PubMed) and ScienceDirect, from their beginning until June 15, 2023, were searched for related publications. In both electronic databases, the following search strategy was applied and the following keywords were used (in title/abstract): “food OR drink” AND “antiepileptic OR antiseizure.” We included all original human studies (including case series and reports) and articles written in English. We excluded all non-original publications (i.e., letters, reviews, and opinions) and animal studies. Two authors (N.M., K.F.) independently participated in the screening, eligibility, and inclusion phases of the study. They collected the full manuscripts for all the publications that appeared to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In case of any uncertainty, they resolved disagreements through discussions. These authors also scanned the reference lists of the previous publications (including reviews) in order to add any relevant published materials. The following data were extracted from the included publications: study's first author, year of publication, study design, and main results. Level of evidence of the included studies were determined following the https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009.11 We also reviewed the drug information documents (websites) of all ASMs.

3 RESULTS

The primary search yielded 738 studies (Figure 1). After implementing our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we could identify 19 studies on the issue of interest for our endeavor (Table 1).12-30 Since all these studies had significant limitations (e.g., mostly were case series with sample sizes below 15 people and phase 1 trials), a critical appraisal was not considered necessary and the risk of bias was not investigated. However, we used the data from these studies and also other published materials (e.g., previous reviews, drugs' websites) to generate the following text on the interactions between ASMs and food and drinks.

| References | Methods | Main results |

|---|---|---|

| Melander et al.12 | The effect of food intake on the absorption of phenytoin was investigated in eight healthy volunteers, by studying single-dose kinetics after ingestion of phenytoin 300 mg either with breakfast or on an empty stomach | Intake of phenytoin with food appeared to accelerate absorption of the drug; peak concentrations were significantly higher (mean increase 40%) in the postprandial state than in the pre-prandial state |

| Levy et al.13 | Six adult healthy volunteers received a single 500 mg dose of sodium valproate in randomized treatments: fasting, with a meal, or 3 h after a meal | Food intake was delayed, but did not decrease the extent of absorption of valproate from an enteric coated formulation |

| Johansson et al.14 | The effects of carbohydrate, fat, and protein on phenytoin absorption were examined in 10 healthy volunteers | Fat had no significant influence, carbohydrates may increase, and protein may decrease the absorption of phenytoin |

| Degen et al.15 | An open, randomized, two-way change-over study. Six healthy, male volunteers received single oral dose of 600 mg oxcarbazepine after overnight fasting or a fat- and protein-rich breakfast | When oxcarbazepine was given with food, the mean AUC increased by 16% and Cmax by 23% |

| Doose et al.30 | Topiramate was given to 28 male participants (single oral doses of 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1200 mg) in a phase I study | This study showed a slight reduction in the rate (~10% decrease in mean Cmax and mean Tmax), but not the extent of absorption when topiramate was given with food |

| Gidal et al.40 | Ten healthy volunteers were administered (in a randomized, cross-over design) a single 600-mg dose of gabapentin in the fasting state and after a high-protein meal | Cmax was significantly increased by 36% after the high-protein meal. Although AUC was increased by 11%, this did not reach statistical significance |

| Retzow et al.16 | The pharmacokinetics of a carbamazepine slow-release preparation were studied after a 12-h fast and also after a standardized breakfast in 24 healthy male volunteers | There was a small increase in mean values of AUC and Cmax when the drug was given with food. The rate of absorption of the slow-release carbamazepine formulation did not change in the presence of food |

| Benetello et al.39 | The interactions between gabapentin (GBP) and food in 12 patients with epilepsy while in a fasting state and after a high-protein meal were studied | No significant differences were seen in GBP serum or saliva concentrations or in its urinary excretion between fasting and after the high-protein meal |

| Grag et al.17 | The pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine were studied after drug administration with 300 mL water or kinnow juice in a randomized crossover trial on nine healthy male volunteers | With kinnow juice, Cmax and AUC were significantly increased and Tmax was significantly decreased as compared with water. However, no change was seen in the elimination half-life of the drug |

| Grag et al.18 | Ten patients with epilepsy who had received treatment with 200 mg carbamazepine three times a day were studied. They were given either grapefruit juice or 300 mL water at 8 am along with 200 mg carbamazepine | Compared with water, grapefruit juice significantly increased the steady peak concentration, trough concentration, and AUC of carbamazepine |

| Cardot et al.19 | The effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of rufinamide were tested in 12 healthy volunteers; they received single doses of 600 mg of rufinamide orally after an overnight fast or a high-fat, high-protein breakfast | Rufinamide with food caused an increase in average AUC by 44% and the Cmax by about 100%. The Tmax was shorter (8 h in fasted state and 6 h in post-breakfast feeding). The terminal half-life was not affected by concomitant food intake |

| Fay et al.20 | In an unblinded, three-way crossover study of 10 healthy volunteers, after an overnight fast, the participants received a single dose of 500 mg levetiracetam taken as an intact tablet with 120 mL of water or crushed and mixed with 4 oz of applesauce, or 120 mL of a common enteral nutrition formulas | The rate and extent of absorption of oral levetiracetam were not significantly impaired after crushing and mixing the tablet with a food vehicle or an enteral nutrition formula |

| Sharma et al.21 | A randomized, open-label, three-treatment, three-course, single-dose, crossover study was done on nine healthy male volunteers to investigate the effects of food on the bioavailability of lamotrigine. A single dose of lamotrigine (100 mg) was administered on three occasions: after a North Indian diet (high-calorie, high-fat), after a South Indian diet (low-calorie, low-fat), and after an overnight fast | A statistically significant reduction in the rate and amount of absorption was observed with the North Indian diet and the South Indian diet compared to the fasting state. The presence of both types of food decreased the average values of Cmax and AUC and decreased the bioavailability of lamotrigine |

| Lal et al.22 | A randomized, open-label, crossover study of 1200 mg gabapentin enacarbil was done in 10 healthy adults, under four conditions: fasted, or following low-fat, moderate-fat or high-fat meals | Administration of gabapentin enacarbil with food enhanced its exposure compared with fasted condition, regardless of the fat or calorie content |

| Kang et al.23 | A 49-year-old man with focal seizures has been treated with phenytoin for over 10 years. Despite medication adherence, persistent subtherapeutic phenytoin levels, resulting in poor seizure control were observed (noni juice was administered daily) | Noni juice probably induced cytochrome P-450 2C9 metabolism of phenytoin |

| Clark et al.24 | A randomized, open-label, single-dose study was done to investigate the bioequivalence of 200-mg topiramate extended-release capsules sprinkled onto soft food (applesauce) versus the intact capsule in 36 healthy adults | The AUC and Cmax for topiramate beads sprayed on applesauce were similar to intact capsules |

| Xu et al.25 | The effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of rufinamide in 10 healthy volunteers was assessed | Food increased Cmax and AUC by 17.4% and 30.8%, respectively, compared with fasted conditions |

| Gammaitoni et al.26 | The effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of fenfluramine was studied in 13 healthy volunteers in an open-label, crossover, phase I study; they received 2 doses of 0.8 mg/kg fenfluramine hydrochloride oral solution, 10 h after an overnight fast and also 30 min after starting to consume high-fat breakfast | Food had no effects on the rate or extent of absorption and bioavailability of fenfluramine |

| Wang et al.27 | Investigation of the pharmacokinetics of levetiracetam extended-release (ER) tablets in 34 Healthy male volunteers was done in a four-way single-dose crossover study between fasted ER and fed ER levetiracetam | The effect of food on the absorption of levetiracetam ER tablets was not significant, but Cmax was increased and Tmax was delayed |

| Taylor et al.28 | The study consisted of three arms: single ascending dose of cannabidiol (CBD), multiple doses, and food effect (1500 mg CBD single dose, n = 12) | A high-fat meal increased CBD plasma exposure (Cmax and AUC by 4.85- and 4.2-fold, respectively); there was no effect of food on Tmax or terminal half-life |

| Birnbaum et al.36 | A single dose of 99% pure CBD capsules was taken under fasting and also fed (high fat) conditions by eight adults with focal epilepsy | On average Cmax was 14 times and AUC four times higher in the fed state |

| Crockett et al.37 | The pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol (CBD) was investigated in healthy adult volunteers following a high-fat/calorie meal (n = 15), a low-fat/calorie meal (n = 14), whole milk (n = 15), or alcohol (n = 14), relative to the fasted state (n = 29) | CBD and metabolite exposures were most affected by a high-fat/calorie meal. CBD exposures also increased with a low-fat/calorie meal, whole milk, or alcohol, but to a lesser extent |

| Welty et al.29 | As a part of the statistical analysis of factors influencing lamotrigine pharmacokinetics in the Equigen chronic dose study, the authors collected data from 33 patients on their use of coffee | Higher consumption of coffee was associated with a significantly lower AUC and Cmax of lamotrigine |

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Interactions between ASMs and foods

Interactions between foods and ASMs are potentially a common phenomenon.9 Many factors may play a role for such an interaction to come to play; these include drug properties, administration route, and administration schedule, among others. Therefore, it is important to have a good knowledge of these potential variables. For example, it is crucial to know whether a specific drug should be taken with or without meals (Table 2). Underestimating such interactions may result in loss of seizure control or unwanted adverse effects.31

| ASM | Administration with regard to food | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Acetazolamide | May be taken with or without food. Food does not affect bioavailability. Administer with food to decrease gastrointestinal adverse effects |

Do not use fruit juice to disguise the bitter taste of the drug. Short-acting tablets may be crushed and suspended in cherry or chocolate syrup to disguise the bitter taste of the drug |

| Brivaracetam | May be taken with or without food | Swallow the whole tablet and do not chew or crush |

| Cenobamate |

Cenobamate may be taken with or without food. Swallow tablets whole with liquid. Do not crush or chew. |

No clinically significant differences in cenobamate pharmacokinetics were observed following administration of a high-fat meal. |

| Clobazam | May be taken with or without food | NA |

| Clonazepam | May be taken with or without food | Grapefruit may increase the serum level |

| Cannabidiol | Take consistently either in the fasted or fed state | High-fat meals significantly increase absorption. Consistent intake with fat-rich food would increase exposure and decrease the costs |

| Carbamazepine | Administer with meals or with a large amount of water to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects | Serum levels may be increased if taken with grapefruit or pomegranate juice |

| Eslicarbazepine | May be taken with or without food | Food has no effect on the pharmacokinetics of eslicarbazepine |

| Ethosuximide | Administer with food or milk to decrease gastrointestinal adverse effects | Grapefruit may increase the serum level |

| Everolimus | Administer consistently with food or consistently without food | Grapefruit, grapefruit juice, and other foods/drinks that are known to inhibit cytochrome P-450 and PgP activity may increase everolimus exposure and should be avoided |

| Fenfluramine | May be taken with or without food. | See the text |

| Gabapentin | May be administered without regard to meals; however, administration with meals may minimize adverse gastrointestinal effects | Capsules may be opened and sprinkled on food (e.g., applesauce, orange juice, pudding) for patients unable to swallow the capsules. The fat content of foods may affect its absorption |

| Ganaxolone | Administer with food | When ganaxolone was administered with a high-fat meal, the Cmax and AUC increased by threefold- and twofold, respectively, when compared to administration under fasted conditions |

| Lacosamide | May be taken with or without food | Food does not affect the rate and extent of absorption |

| Lamotrigine | Administer without food (fasted) | Tablets must be swallowed whole and must not be chewed, crushed, or divided |

| Levetiracetam | May be taken with or without food | The extent of bioavailability of levetiracetam is not affected by food |

| Oxcarbazepine | May be taken with or without food | Food has no effect on the rate and extent of absorption of oxcarbazepine |

| Perampanel | May be taken with or without food | Food does not affect the extent of absorption, but slows the rate of absorption |

| Phenobarbital | May be taken with or without food | For patients with difficulty swallowing, tablets may be crushed and mixed with food or fluids |

| Phenytoin | It may be best to administer on an empty stomach or in a consistent manner in relation to food to avoid bioavailability problems | Concurrent intake of food and phenytoin may affect the drug absorption |

| Rufinamide | Administer with food | Studies have indicated an increase in the bioavailability and absorption of rufinamide when this medication is administered with meals |

| Topiramate | May be taken with or without food |

The bioavailability of topiramate is not affected by food. Because of the bitter taste, the tablets should not be broken The contents of the capsules may be sprinkled on a small amount of soft food (e.g., applesauce, ice cream, or yoghurt) for administration. Drink 6–8 glasses of water a day |

| Valproic acid | May be administered with food or with a large amount of water to minimize gastrointestinal irritation |

In order to prevent local irritation to the mouth and throat, capsules should be swallowed whole Do not mix oral solution with carbonated beverages, because it may cause local irritation of the mouth and throat |

| Zonisamide | May be taken with or without food |

In the presence of food, the time to maximum concentration is delayed, but food has no effect on the bioavailability of zonisamide Swallow the capsules whole with a drink of water. Do not bite into or break open the capsule. Drink 6–8 glasses of water a day. Grapefruit can increase the serum level |

4.1.1 Phenytoin

Concurrent intake of food and phenytoin may affect the drug absorption.12 High-protein meals may delay the absorption of phenytoin.32 Similarly, phenytoin absorption may be affected by the dietary content of carbohydrates.14, 33 In one study of 10 healthy volunteers, the nutrients (carbohydrate, fat, and protein) were delivered separately (as much as those in a routine breakfast). Phenytoin concentrations were measured in plasma. The results showed that, while fats had no significant effects, carbohydrates may increase and proteins may decrease the absorption of phenytoin.14 Furthermore, decreased serum phenytoin concentration has been associated with enteral feeding.34 It has been suggested to stop the enteral feeding from 2 h before until 2 h after the administration of phenytoin.35 The interactions between enteral feeding and phenytoin (and other drugs) were not the target of this systematic review, however. For further reading, you may refer to the review by Au Yeung and Ensom34 [Note: there was no information on the interactions between enteral feeding and new ASMs (brivaracetam, cannabidiol, cenobamate, eslicarbazepine, fenfluramine, ganaxolone, lacosamide, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, and rufinamide) in their drug information packages].

4.1.2 Cannabidiol

In a phase I study of cannabidiol, the food effect on its absorption was studied in 12 healthy volunteers. A high-fat containing meal (about 1000 kcal) increased the bioavailability of cannabidiol by more than fourfold.28 Two other studies had similar observations of multifold increase in the Cmax and bioavailability of cannabidiol when consumed with high-fat containing meal.36, 37 In one study, fat addition to the fed digestion significantly increased the bio-accessibility of cannabidiol. The food matrix that was used was a blend of olive oil and baby food; the fed-state digestion showed significantly higher micellarization efficiency for cannabidiol than the fasted-state digestion of cannabidiol. The authors suggested consuming cannabidiol with food high in fat to enhance micellarization and optimal absorption of the drug.38 It is suggested to consistently administer the drug either with or without food (Table 2). Another strategy is to consistently use cannabidiol with some fat in meals. This may significantly reduce the dose needed and the cost. The ideal strategy to consume cannabidiol in order to increase its effects and decrease its costs, while maintaining a healthy diet (balanced in fat content) should be clarified with further studies.

4.1.3 Gabapentin

Gabapentin is well known to have saturation kinetics in its absorption, dependent on the L-amino acid transporter carrier. In one study of 10 subjects, the mean bioavailability of gabapentin enacarbil was 42% (fasted), 64% (low-fat meal), and 76% (high-fat meal). Gabapentin exposure in fed condition (23% for the low-fat meal and 40% for the high-fat meal) was more than the exposure under fasted condition.22 However, in one study, no statistically significant differences were observed in gabapentin serum or saliva concentrations or in its urinary excretion between fasting and after a high-protein meal.39 Another study of 10 healthy volunteers, who received in a randomized, cross-over design, a single 600-mg dose of gabapentin in the fasting state and after a high-protein meal, showed that Cmax was significantly increased by 36% after the high-protein meal.40 Although AUC was increased by 11%, this did not achieve statistical significance, possibly due to the fact that there were not more than 10 individuals included in the study40 and also the inter-patient variability in the absorption of gabapentin is noticeable.41 Potential mechanisms to explain this finding may be that the large amino acid load delivered with the high-protein meal enhanced gabapentin absorption via trans-stimulation, the process by which acutely increased intestinal luminal amino acid concentrations result in an acute up regulation in System-L activity.40

4.1.4 Rufinamide

Two studies have indicated an increase in the bioavailability and absorption of rufinamide when this medication is administered with meals.19, 25 In one study, after delivery of a single dose (200 mg) of rufinamide the plasma drug concentration was higher in the fed condition compared with that without food.25 It is suggested to consistently administer the drug with food.

4.1.5 Carbamazepine

In the case of carbamazepine, studies have indicated an increase in the bioavailability and absorption of the drug when this medication is administered with meals.16 In one study, the pharmacokinetics carbamazepine (slow-release preparation) was studied after a 12-hour fast and after a routine breakfast in 24 healthy volunteers (men); there was a small increase in mean values of AUC and Cmax when carbamazepine was given with food.16

4.1.6 Valproate

One study showed that food intake delays, but does not diminish the extent of absorption of valproate from an enteric coated formulation.13

4.1.7 Topiramate

One study investigated the bioequivalence of topiramate extended-release capsules sprinkled and intact capsules in 36 healthy adults. The authors concluded that for patients with difficulty swallowing pills, topiramate extended-release capsules sprinkled onto applesauce offers a useful once-daily option for taking topiramate.24 Another study investigated the ability of foods/drinks to decrease the bitterness of topiramate. The inhibitory effects of foods and drinks (yoghurt and other foods and drinks) on the bitterness of topiramate were tested with a taste sensor using a bitterness-responsive membrane. The authors concluded that yoghurt is probably the food most effective in decreasing the bitterness of topiramate without compromising the taste of the food itself.42 One study showed a slight decrease in the rate (approximately 10% decrease in mean Cmax and mean Tmax approximately 2 h later), but not the extent of absorption when topiramate was taken with food.30

4.1.8 Oxcarbazepine

One study investigated the effects of food on the disposition of oxcarbazepine in six healthy volunteers.15 The authors concluded that the effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of oxcarbazepine is minimal and it should be of little therapeutic concern.15

4.1.9 Levetiracetam

One study investigated the oral absorption kinetics of levetiracetam (the effect of mixing with food or enteral nutrition formulas).20 The authors concluded that the overall rate and extent of absorption of oral levetiracetam were not significantly affected after crushing and mixing of the tablet with either a food vehicle or a typical enteral nutrition formula product.20 Another study showed that food did not affect the absorption of the levetiracetam extended-release tablet, but the Cmax increased and the Tmax was delayed.27

4.1.10 Lamotrigine

One study suggested that lamotrigine should preferably be taken in a fasting condition, as presence of food may decrease the bioavailability to a significant extent.21

4.1.11 Fenfluramine

One study showed that food had no effects on the rate or extent of absorption and bioavailability of fenfluramine.26 As for fenfluramine, perampanel and cenobamate are not generally influenced by food. For other drugs, please refer to Table 2.

4.2 Interactions between ASMs and drinks (non-alcoholic)

Cytochrome P-450 (CYP) enzymes inhibition by some fruit juices (e.g., grapefruit, lime, pomegranate, kinnow, black mulberry, wild grape, and star fruit) may be associated with an increase in serum concentrations of some drugs (e.g., carbamazepine, ethosuximide, clonazepam, felbamate, and zonisamide).9, 10, 17, 18 PWE should keep away from excessive consumption of such fruit juices.10 The inhibitory potential of human CYP-3A by grapefruit juice is more than other fruit juices; therefore, it has more clinical significance. Grapefruit juice may increase the likelihood of carbamazepine toxicity through inhibition of CYP-3A4 enzymes.17, 18, 43, 44 In one study, 10 PWE, who had received therapy with carbamazepine (200 mg three times a day) for 3–4 weeks, were given either grapefruit juice or 300 mL water at 8 am along with their carbamazepine. Compared with water, grapefruit juice significantly increased the steady peak concentration (6.55 vs. 9.20 μm/mL), trough concentration (4.51 vs. 6.28 μm/mL), and area under the plasma concentration–time curve (43.99 vs. 61.95 μm.h/mL) of carbamazepine.18

Caffeine may induce hepatic CYP-1A enzymes. These enzymes are also important for the metabolism of many drugs including carbamazepine; thereby, caffeinated drinks may reduce carbamazepine serum levels.9, 10 In one study, the steady state serum concentrations of carbamazepine in patients, who were regular tea drinkers, were significantly increased after 7 days of stopping tea consumption.45 Also, in one study, with increasing consumption of coffee, the plasma exposure of lamotrigine decreased significantly, indicating potential induction of its metabolism.29 Finally, cola-containing drinks (e.g., Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Sprite) are among the most commonly consumed drinks in the world. These drinks are acidic and include caffeine; these two properties may cause interactions between cola-containing drinks and some drugs (e.g., carbamazepine and phenytoin).46 Drugs-foods (−drinks) interactions that give rise to more than a 50% change in drug exposure or plasma levels of drugs usually require dosage adjustments.47 Table 2 shows the ASMs and food/drinks interactions.48-72

5 CONCLUSION

Interactions between ASMs and foods and drinks are common and important. This should be taken seriously into consideration when consulting patients and their caregivers about ASMs. Drugs–foods (−drinks) interactions may change the drug exposure or plasma levels of drugs and may require dosage adjustments. Future investigations should explore the specific interactions between foods (and drinks) and various ASMs to clarify whether they are clinically important.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ali A. Asadi-Pooya: study design, review process, manuscript preparation. Cecilie Johannessen Landmark, Nafiseh Mirzaei Damabi, Khatereh Fazelian: review process, manuscript preparation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Svein I. Johannessen, Dr. Mina Shahisavandi and Dr. Iman Karimzadeh are acknowledged for their valuable inputs to the manuscript. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Ali A. Asadi-Pooya: Honoraria from Cobel Daruo, Actoverco; Royalty: Oxford University Press (Book publication). Cecilie Johannessen Landmark has received advisory board/ speaker's honoraria from Angelini, Eisai, Jazz and UCB Pharma. Others: none.