The Relationship Between Social Identification and System Justification: A Meta-Analytic Test of Relevant Moderators

Funding: The authors did not receive support from any organisation for the submitted work.

ABSTRACT

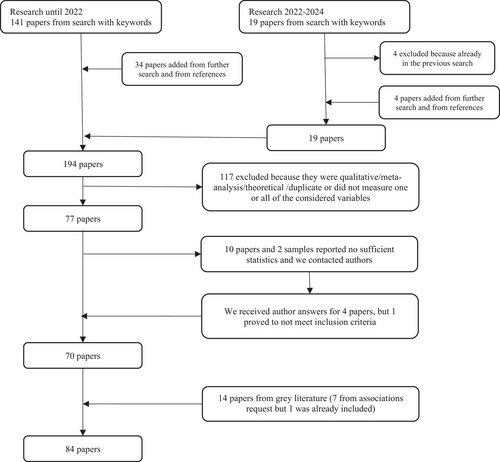

The association between social identification and system justification, especially amongst low-status groups, is a highly contested issue in the social and political psychology literatures. While some researchers propose that this association should be largely negative, others assume that it should be largely positive. Here, we synthesised the accumulated evidence on this relationship using a 4-level meta-analysis of 84 papers supplying 248 different samples and 359 effect sizes (Ntotal = 395,855). Overall the association between identification and system justification was positive, although weak (Zr = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.17) and was stronger for high- and intermediate-status groups (Zr = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.25 and Zr = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.04, 0.20 respectively) but null for low-status groups (Zr = 0.01, 95% CI = −0.04, 0.06). When theoretically relevant moderators were taken into account, the results further revealed that, for low-status groups, subgroup identification was positively correlated with system justification, but only when status differences were stable and/or legitimate.

1 The Relationship Between Social Identification and System Justification: A Meta-Analytic Test of Relevant Moderators

It is not difficult to imagine people who are disadvantaged by prevailing societal arrangements seeking some kind of restitution instead of resigning to their fate. Several concrete examples of change to the existing social system abound, such as the fall of Nazism and Fascism, slavery abolition, the fall of Berlin Wall and some historically inequitable gender policies/laws (e.g., those prohibiting abortion or LGBTQIA+ individuals’ rights). Such struggles are not restricted to the past. We witness today several challenges to the status-quo amongst the disadvantaged, ranging from the Black Lives Matter and ‘I Can't Breathe’ movements advocating racial equality in law enforcement; through the #MeToo global movement that spotlights gender inequality, to pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, all drawing attention to civil liberty issues and corrupt systems. Widespread as these examples of social change might seem, it is also the case that instances of social stasis occur in which the disadvantaged, rather than challenging realities that undercut their personal and/or collective interests, acquiesce to them or, in some cases, embrace such systems (e.g., working class Trumpism in the United States). But is this so-called system justification (Jost and Banaji 1994) more prominent amongst strongly or weakly identifying group members, especially those belonging to disadvantaged groups? This question is relevant given that both the system justification theory (SJT; Jost 2019; Jost and Banaji 1994; Jost et al. 2019, Jost et al. 2023) and the social identity model of system attitudes (SIMSA), a recent extension of the social identity approach (i.e., Tajfel and Turner 1979; Turner et al. 1987), place largely contrasting emphasis on the relationship between group needs and support for existing social arrangements.

To begin with, both the social identity and system justification research traditions accept that people (including members of groups that are disadvantaged by the prevailing system) sometimes accept and even support the societal arrangements in which they operate. Also, both theoretical accounts seem to accept that the hierarchical level of group attachment has an important influence on the relationship between social identification and system justification. That is, it matters whether we consider social identification at the subordinate level (e.g., African American or White American) or the superordinate level (e.g., American). However, the two theories diverge sharply in their expectations about whether system-supporting attitudes should be prevalent amongst weak group identifiers (i.e., ruling out group-based motives as a likely cause; Jost and Banaji 1994) or amongst strong group identifiers (i.e., implicating group-based motives as a potential cause of system attitudes; Owuamalam et al. 2019a; Rubin et al. 2023a, 2023b). Here, we provide a systematic meta-analytic synthesis of the existing body of evidence on the association between group identification and system justification among members of high and low status groups.

1.1 SJT

In their seminal treatise of SJT, Jost and Banaji (1994) proposed the existence of a novel system justification motivation that is unique in the sense that it is different and separate from the ego- and group-justification motivations connected with personal and social identities. According to system justification scholars, this novel system justification motivation—rooted in multiple needs like, inter alia, cognitive, existential, epistemic and relational drives—is necessary to explain the occurrence of system justification (see also Jost 2020). This unique need is thought to motivate people to maintain the belief that the existing system is just and legitimate (e.g., Jost 2020; Kay et al. 2009), although other auxiliary enabling conditions also play a role (see Owuamalam et al. 2019a, 404, for a more complete list). SJT researchers have emphasised that the system justification motive is only consonant with the group-justification motivation of those who belong to groups that are advantaged by the status quo and that it conflicts with the group motive of those who belong to groups that are disadvantaged by the relevant systems. More precisely, for advantaged groups, group and system motives are theorised as being separate but congruent with one another because they push towards the same outcome (i.e., to justify realities that already benefit their self, their social group and their society). In contrast, for disadvantaged groups, group-justification motive conflicts with system-justification motive because evaluating the system as just also implies acknowledging that the ingroup's disadvantage is just. For this reason, SJT assumes that system justification should be most visible amongst the disadvantaged when group identification and interests are sufficiently weak to not interfere with the system motive (Jost and Banaji 1994; Jost et al. 2003). That is, when one considers the disadvantaged, a negative relationship between social identification and system justification should emerge, as identification with low-status group would enhance ingroup justification motivation, which in turn would interfere with system justification motivation. As Jost et al. (2003, 17) pointed out: ‘for members of low-status or disadvantaged groups a negative relation generally holds between group identification (or group justification) and system justification’. On the contrary, for advantaged groups, system justification and ingroup identification are assumed to be congruent, that is, they do not interfere with one another. Hence, Jost et al. (2017, 104) hypothesises that ‘in-group identification should be positively associated with system justification for those who are advantaged but negatively associated with system justification for the disadvantaged (see also Osborne et al. 2019).

However, a distinction should also be made with respect to the hierarchical level of social identification being considered. It is worth noting that a subordinate level of identification (Turner et al. 1987) refers to identification with a subgroup (e.g., African Americans) embedded in a broader/extended group (e.g., America), and this could be further characterised in terms of whether the identity in question is non-politicised or highly politicised (e.g., an identity built around opposition to the status quo, such as the feminist identity,1 see Simon and Klandermans 2001; van Breen et al. 2017; van Stekelenburg et al. 2013). The SJT assumption that system justification motive should be inversely associated with subordinate ingroup identification seems most evident when politicised identity is considered (which is a subgroup identity involving perception of systemic group-based inequality resulting in a feeling of injustice, e.g., Klandermans 2014; Rao and Power 2021). Indeed, according to SJT, politicised identification has been shown to be inversely related to system justification and positively related with collective actions challenging the existing system (Drury and Reicher 2000; Jost et al. 2017; van Zomeren et al. 2008).

Social identification can also operate at a more inclusive superordinate level, referring to commitment to an extended/larger ingroup (e.g., Americans). While the distinction between subordinate and superordinate identification was not considered in the initial formulation of SJT (given that it was assumed that system motive is unconnected to an ‘extended collective ego’, Jost and Banaji 1994, 10), some SJT's postulations seem to imply that people have some kind of relationship (e.g., identification) with the system. For example, Jost et al. (2004, 908, emphasis added) stated that ‘people have psychological attachments to the status quo that supersede considerations of self-interest’, and Liaquat et al. (2023, 136, emphasis added) highlighted that ‘people are motivated to hold favorable views toward the overarching social systems that govern their lives’. These statements suggest that SJT now admits the possibility that people feel connected with, and are biased in favour of, the existing system they live within (which, by the way, meets the criterion for group formation, according to Turner and Bourhis 1996, 34). Accordingly, national identification (i.e., the superordinate level) is often found to be positively associated with system justification amongst members of both high and low status groups (e.g., Caricati et al. 2021; Gustavsson and Stendahl 2020; Moscato et al. 2021; Owuamalam et al. 2023; Vargas-Salfate et al. 2018), even in the evidence supplied by researchers from the system justification tradition (e.g., Van der Toorn et al. 2014). This evidence has presumably led to the recognition within SJT tradition that superordinate identification (i.e., national identification), but not subordinate identification, may be positively associated with system justification after all. As Jost et al. (2023, 18) stated, ‘it makes perfect sense to us that system justification among the disadvantaged would be positively associated with […] national identification’.

This latest proposition by SJT researchers is somewhat close to a suggestion under the social identity approach that when superordinate identification is activated, both advantaged and disadvantaged people are likely to justify the superordinate system in an attempt to favour their superordinate ingroup (in this case, system justification may be an ingroup bias at the superordinate level). In the following, we turn our attention to the social identity approach to system justification.

1.2 The Social Identity Approach

SJT's account has been criticised by social identity scholars (e.g., Reicher 2004; Rubin and Hewstone 2004; Spears et al. 2001) as lacking theoretical flexibility to consider contextual conditions in which dominance and subordination appear. More recently, SJT's account has been directly challenged by the proponents of the SIMSA, which is a social identity-inspired model that focuses primarily (though not exclusively) on system justification among the disadvantaged (Owuamalam et al. 2019a, Owuamalam et al. 2019b; Rubin et al. 2023a, 2023b). According to the social identity approach, there is insufficient evidence to sustain the idea that the occurrence of system justification is induced by a unique system justification motive that is completely devoid of any self/group-based interest (Owuamalam et al. 2019a; Owuamalam and Spears 2020; Rubin and Hewstone 2004). SIMSA proposes that system justification can be interpreted as the outcome of the interaction between group interests and the contextual conditions in which groups live and that system justification could be largely more parsimoniously interpreted as a group-based attitude. With respect to group status, the social identity approach suggests that advantaged groups should be more motivated to maintain the status quo (i.e., justify the system) because they derive positive social identity from the existing social system (e.g., Owuamalam et al. 2025)—not necessarily because they are motivated to defend the system for the sake of doing so, and outside any material or symbolic self/group interests.

When it comes to low-status groups, the social identity approach, and SIMSA in particular, expects that system justification is due to several processes that are rooted in social identification (e.g., see Rubin et al. 2023a, 2023b). For example, in line with social identity approach, SIMSA assumes that, when people categorise themselves as being part of a social group (however large this may be), system justification may reflect ingroup bias, an inclination towards ingroup reputation management or conformity to the norms of that ingroup (see also Reicher 2004; Turner et al. 1987). SIMSA assumes that these system-justifying processes (e.g., ingroup bias, ingroup reputation management, norm conformity, etc.), being rooted in group processes, should be more evident amongst strongly (not weakly) identifying members of disadvantaged groups and in particular contexts. For example, one crucial contextual aspect with respect to low-status group members’ reaction to inequality is the perception that status differences are stable2 and legitimate. When people believe that the existing social hierarchy is illegitimate and unstable (such as when they encounter or live with a politicised identity), the social identity approach envisages that people will be more likely to challenge the existing social arrangement to the extent that they identify with this politicised subgroup identity (e.g., van Zomeren et al. 2008, 2018). Accordingly, several scholars agree that a legitimate and stable system is more likely to be perceived as just than an illegitimate and unstable system (e.g., Cichocka and Jost 2014; Jost 2017; Tajfel and Turner 1979; van Zomeren et al. 2018). Under such conditions of legitimacy and stability, most of the group processes that SIMSA envisages as explanations for system justification (e.g., ingroup reputation management, norm conformity, hope for future ingroup status) are expected to be positively linked to ingroup identification. Hence, according to SIMSA, a positive association between social identification and system justification should be the more likely outcome amongst disadvantaged groups at both the subordinate and superordinate levels of self-categorisation, when the social hierarchy is stable and legitimate, provided the relevant subgroup identity is not a politicised one.

The one situation in which SIMSA envisages a negative relationship between subgroup identification and system justification in a context of stable and legitimate social stratification is when the need for collective social accuracy constraints/curtails group-interested attitudes. Here, subgroup identification could be inversely related to system justification because (a) weak group identifiers ought to be less hesitant than their strongly identifying counterparts to accept the prevailing social reality (Rubin et al. 2023a, 207), especially when (b) they are invested in a superordinate identity that subsumes their disadvantaged subgroup identities (Owuamalam et al. 2024).

-

According to SJT, the relationship between system justification and subgroup identification is negative for low-status groups (Jost et al. 2003, 17) and positive for high-status groups (Jost et al. 2017, 104). In contrast, SIMSA/SIT suggests that the relationship between system justification and group identification is generally positive for both high- and low-status groups, as long as social stratification is stable and legitimate (Rubin et al. 2023a).

-

Both SJT (Jost et al. 2017) and SIMSA/SIT (van Zomeren et al. 2018) expect that politicised identification is negatively related to system justification.

-

SJT now recognises that superordinate identification should be positively associated with system justification (Jost et al. 2023, 18). This idea is rooted in the SIT tradition and is similarly embraced by the SIMSA perspective (Rubin et al. 2023a).

1.3 Overview of the Meta-Analysis

Despite the relevance both camps place on the link between system justification and social identification, research has not led to agreement about either the strength, direction, or theoretical reason for the association between these two constructs. Hence, to provide a quantitative assessment of these issues, a meta-analytic synthesis of the accumulated data becomes all the more important. In this investigation, we provide (a) the summary effect size and variability of the social identification-system justification relationship, and (b) the direction and strength of this association with respect to two key moderators: group status and the hierarchical level of social identification. We also spotlight the data for low-status groups in our analysis in order to maintain a constant connection with the principal contentions between SJT and SIMSA. That is, system justification among low-status groups is the aspect that (a) is more complex to understand because it seems puzzling and (b) most clearly demarcates the difference between SJT and SIMSA accounts of system justification. Thus, a focus on low-status groups is of particular relevance from both theoretical and practical standpoints.

2 Method

2.1 Selection of Studies

-

had a measure of system justification. Indeed, the question of what constitutes a social system—and, by extension, system justification—has been the subject of ongoing debate (e.g., Owuamalam et al. 2018, 2). In light of this, we adopted a narrow operationalisation of system justification, focusing on measures that directly capture active support for the prevailing order, consistent with Jost and Banaji's (1994, 1, our emphasis) definition of system justification as the ‘preservation of existing social arrangements even at the expense of personal and group interests’. Consequently, we excluded related but distinct measures reflecting dispositional traits (e.g., SDO, see also Jylhä and Akrami 2015, 109) or stereotypical depictions of certain groups that may represent more enduring ideological tendencies rather than dynamic, context-driven processes (see also Jost and Hunyady 2005, 260; Vargas-Salfate et al. 2018, 1063). That is, we focused on process-oriented operationalisations that better reflect system justification as an active/motivated psychological mechanism (e.g., actual evaluations and/or legitimation of existing social arrangements/hierarchies or relationships within the system). In short, we excluded any measures that did not directly assess engagement with the existing ‘state of affairs’, ensuring that the justification measures in our analysis specifically reflected an orientation towards the functioning of the prevailing order rather than capturing broad ideological beliefs or prejudicial attitudes towards particular groups;

-

contained a measure of social identification with a specific group/collective;

-

reported sufficient/relevant statistics to compute effect size (e.g., r, standardised beta, unstandardised beta, n).

Two researchers independently reviewed the retrieved records to ensure consistency with the inclusion criteria. The inter-rater agreement on including or excluding papers was very high (96%). In a subsequent meeting, they resolved any discrepancies by reviewing and discussing the papers, ultimately reaching a complete consensus on which papers should be included or excluded. The two most common reasons for exclusion were that studies did not include a measure of identification or system justification (88.5%). Seven further records (6%) were excluded because they were theoretical or qualitative papers. These criteria left 84 studies eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

2.2 Coding of Studies

-

measures referring to the functioning of a general system as general system justification (k = 187, e.g., ‘In general, I find society to be fair’);

-

measure referring to relationship between genders as gender system justification (k = 57, e.g., ‘In general, relations between men and women are fair’) including belief about system sexism (e.g., ‘Society has reached the point where women and men have equal opportunities for achievement’ reverse);

-

measures referring to the evaluation of the prevailing economy as economic system justification including meritocratic beliefs (k = 22, e.g., ‘Generally, social class differences reflect differences in the natural order of things’);

-

measures referring to evaluation of general subsystems in a nation as justification of government and state's apparatus (k = 28, e.g., ‘Italian laws are enforced based on accurate information’);

-

measures referring to evaluation of functioning of system linked to healthcare and education as healthcare and educational system justification (k = 25, e.g., ‘I feel that universities earn the reputation they get’);

-

measures referring to evaluation of fairness of the differences between specific groups as status difference justification (k = 28, e.g., ‘In general, the difference between nurses and physicians is fair’); and

-

measure referring to global beliefs about how just the world is, as belief in a just world (k = 12, e.g., ‘I am confident that justice always prevails over injustice’).

Finally, the main moderators: (i.e., group status and hierarchical level of identification) were coded.

2.2.1 Group Status

With respect to this primary moderator, we identified four different levels: high-status, intermediate-status, low-status and mixed-status3; the latter category refers to samples drawn from the general population of which the particular composition in terms of social categories related to measured social identification was unreported in the paper. Status was coded considering the specific status hierarchy that was taken into account by the study, considering as high status those samples with a privileged social position with respect to the considered status hierarchy, intermediate status those samples that could have an advantaged and a disadvantaged position in the hierarchy being considered, and low status as those samples in which the target group occupied a disadvantaged position in the status hierarchy being considered.

2.2.2 Level of Social Identification

-

national, when items refer to affective, cognitive or evaluative (or all) dimensions of membership in overarching societal group (e.g., one's nationality);

-

subordinate, when items refer to affective, cognitive or evaluative (or all) dimensions of membership in groups that represent segments within societies (e.g., ethnic groups); and

-

politicised sub-group identification, when items refer to affective, cognitive or evaluative (or all) dimensions of membership in groups that represent portions or segments of societies and that are known to support critical viewpoint about the place of the ingroup within the larger social system (e.g., protest movements).

Inter-rater agreement (Krippendorf's alpha for nominal data) was 0.87. Hence, there was sufficient agreement amongst the judges with respect to the categorisation of identification types to retain our approach.

2.3 Effect Size Coding

To code effect sizes, we directly reported Pearson's correlation coefficient. In a few cases (k = 22), standardised or unstandardised regression coefficients were reported but were transformed to r following the formula by Peterson and Brown (2005). If a study reported both Pearson's r and regression coefficients, we recorded the correlation coefficient only. When a sample reported more than one effect size, the effects were inserted in the database and coded as belonging to the same sample and the same study. We included these sources of dependency between effects in our subsequent multilevel meta-analysis (see below).

2.4 Meta-Analytical Procedure

Correlation coefficients were corrected for small sample bias and then transformed to Fisher's Zr. Following Harrer et al. (2022), we excluded 11 samples with Ns ≤ 20 so that we meta-analysed 248 different samples that supplied 359 different effect sizes. These small samples were all from the same study employing a cross-national large sample (Brandt et al. 2020). Given that Fisher's z-transformed correlation is reliable with sample sizes greater than 20 (Hedges 2019), we excluded these samples for the sake of precision in estimations to avoid artificially inflating the heterogeneity of effect sizes (Magraw-Mickelson et al. 2020). In any case, results were unchanged when these small samples were included.

Considering that a number of samples supplied several effect sizes and a number of papers supplied several samples, we decided to take into account sources of variability due to dependency among effect sizes (coming from the same sample) and dependency among samples (coming from the same paper/research) to account for dependency between effect sizes. More precisely, we considered single effect sizes as nested within samples (as each sample could supply different effect sizes), which in turn were considered as nested in papers (as each paper could supply different samples). We then performed a 4-level random meta-analysis in which we tried to consider as many sources of variability as possible. This procedure allowed us to estimate the sampling variance for each effect size (Level 1), the variance among effect sizes coming from the same sample (e.g., within-study variance, Level 2), the variance among studies coming from the same paper (Level 3), and the variance among papers (Level 4).

All meta-analytical procedures were performed in R (R core team 2023) and principally with metafor package (Viechtbauer 2010). For the moderation analysis, we used a meta-regression procedure in which several dummy variables represented categorical moderators with more than two levels.

We performed a meta-analysis on all samples and a further meta-analysis on a subset of samples that only included low-status groups. We used this two-pronged approach because, although support for the existing social system among high-status groups is easy to understand, system justification among low-status groups is the most puzzling effect to explain, and it also provides the most incisive test between the propositions advanced by SJT and SIMSA. Thus, the focus on low-status groups is of particular theoretical relevance.

2.4.1 Sensitivity Analysis

We also performed sensitivity analyses to identify influential cases and outliers in our dataset. To this end, we ran our meta-analyses excluding one observation at a time and observing whether the pooled effect showed a relevant modification. Further, we considered Cook's distance (Cook and Weisberg 1982; similar to Mahalanobis distance) among observations when each observation was included and excluded from the dataset. We also considered standardised residuals in which scores higher or lower than 2.24 (i.e., z-scores of cases above or below the top and bottom 2.5% of the z-distribution) indicated extreme observations (Aguinis et al. 2013). Moreover, we considered hat values (or leverage) whose values are greater than 3*p/k, where p is the number of predictors and k is the number of observations, are considered influential (Viechtbauer 2022). We excluded influential cases to observe whether exclusion would substantially change pooled results.

2.4.2 Publication Bias and Power

In order to evaluate publication bias, and given the complexity of the structure of our analysis, we used a generalisation of Egger's regression test by meta-regressing the model on measures of precision such as the standard error of effect size and reciprocal of sample size. We also performed a p-curve analysis in order to detect publication bias due to p-hacking and the obtained power of our meta-analysis. This analysis tests the right-skewness of the p-curve that indicates that the ‘true’ effect is present in the meta-analysed data, and the flatness of the p-curve, which indicates insufficient power. Moreover, given that p-curve analysis may overestimate power when heterogeneity is high (Brunner and Schimmack 2020), we included also Z-curve analysis using the zcurve package (Bartoš and Schimmack 2020) in r. Z-curve analysis assumes that null hypothesis is false and estimates the expected replication rate (ERR), which refers to the power to find significant result in replications. It is worth noting that we did not expect to find publication bias because most studies that were included in this work were not originally aimed at analysing the relationship between social identification and system justification.

3 Results

3.1 Description of Studies

The dataset consisted of 84 papers supplying 248 different samples and 359 different effect sizes. The papers dated from 1998 to 2024 (Mdn = 2019.50). There were 70 studies (83.30%) retrieved from formally published literature and 14 studies from the grey literature. Sample sizes ranged from 21 to 157,019 (M = 1596.19, SD = 11,014.50, Mdn = 161.50) and totaled 395,855 participants who were on average 62% women (SD = 26%, range = 0%–100%). Participants’ mean age was 28.79 (SD = 8.97, range = 15.74–56.00). 45.16% of samples were from university student populations, 42.74% were from community populations and 9.68% were from populations that contained both students and non-students. For 114 samples (46.0%), no information about the ethnicity of participants was reported, while 33.87% of samples were composed entirely or mostly of White participants. 122 (49.19%) samples came from experimental research, and 126 (50.81%) came from correlational research. No studies manipulated social identification directly while system justification was manipulated in three samples. All studies used explicit measurements. 76 (30.60%) of samples came from North America, 48 (19.40%) from South Europe, 11 (4.40%) from North Europe, 21 (8.50%) from East Europe, 28 (11.30%) from Western Europe, 18 (7.30%) from Oceania and 19 (7.70%) from Asia.

3.2 Pooled Effect

The pooled effect was significant, Zr = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.06, 0.17], r = 0.11, indicating that system justification and social identification were overall positively but weakly correlated with one another. There was a high level of variance, Q(358) = 12,932.99, p < 0.0001, I2 = 98.82, which was mostly due to differences within studies (Level 2: σ2 = 0.04, χ2[1] = 1652.18, p < 0.001, I2 = 44.90) and between papers (Level 4: σ2 = 0.05, χ2[1] = 44.85, p < 0.001, I2 = 53.92), rather than differences within samples (Level 3: σ2< 0.001, χ2[1] < 0.001, p = 0.999 I2< 0.001) and sampling error (Level 1: I2 = 1.18). Thus, results indicated that the strength and direction of the relationship between system justification and social identification was highly variable, suggesting the usefulness of moderator analysis.

3.3 Analysis of Non-Substantive Moderator Variables

For explorative purposes, we tested the effects of several types of moderators that were linked to both research design and sample characteristics. Meta-regression results indicated that the average effect size for the association between social identification and system justification was neither affected by year of publication (b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, t = 1.59, p = 0.113, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.02]), whether papers were from formal or grey literature (F(1, 355) = 0.850, p = 0.357), whether research designs were correlational or experimental (F(1, 357) = 0.08, p = 0.781, the continent on which research was undertaken (F(8, 346) = 1.08, p = 0.378), whether samples were composed of students or not, (F(1, 357) = 0.22, p = 0.643), nor the age of participants, (b = 0.001, SE = 0.002, t = 0.287, p = 0.775, 95% CI [−0.004, 0.005]).

Concerning sample ethnicity (k = 202), and providing early indications of potential status effects, the association between system justification and identification was stronger and positive for White and Asian samples (Zr = 0.17 and Zr = 0.22). For ethnically mixed samples, this relationship was positive (Zr = 0.16), while it was negative for samples composed of mainly Blacks, Latinos or Maori and Pacific Islanders (Zr = −0.17 and −0.07, F(4, 197) = 6.76, p < 0.001). Finally, the association between system justification and identification was reduced when the percentage of females in the sample increased (b = −0.18, SE = 0.05, t = 3.26, p = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.28; −0.07].

We also considered different kinds of system justification that were recoded as a potential moderator. Analysis revealed that the association between social identification and system justification was not affected by the kind of system justification measurement, F(6, 352) = 1.08, p = 0.371, although the association with social identification was stronger for healthcare and academic systems (Zr = 0.21) government and status apparatus (Zr = 0.15), just word belief (Zr = 0.14), general system justification (Zr = 0.13) and economic system justification (Zr = 0.12), while it was weaker for gender system justification (Zr = 0.02) and justification of status differences (Zr = 0.09).

3.4 Analysis of Substantive Moderator Variables

We entered group status (high, intermediate, low and mixed, ks = 98, 44, 166 and 51, respectively), and level of social identification (national, non-politicised subgroup, politicised subgroup, ks = 61, 267 and 31, respectively) into a 4-level meta-regression analysis. Moderators were entered together so that the effect of each one was controlled for the effects of the others.

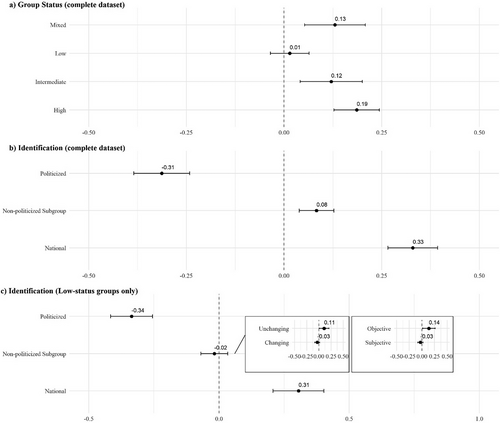

Meta-regression analysis yielded a significant general moderation effect, F(5, 353) = 63.25, p < 0.0001. Figure 2a,b reports the estimated value of the relationship between system justification and social identification at levels of the moderator variables. Group status had a significant effect, F(3, 353) = 12.97, p < 0.001. More specifically, the relationship between system justification and identification was strongest in high-status samples, Zr = 0.19, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.13, 0.24]. This relationship tended to decrease in size for intermediate-status samples, Zr = 0.12, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.04, 0.20] and mixed-status samples, Zr = 0.13, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.05, 0.21], and it was near to zero for low-status samples, Zr = 0.01, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.06]. The difference between the associations for high- and low-status groups was significant (ΔZr = 0.17, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) as did the difference between intermediate- and low-status groups (ΔZr = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = 0.025), but no significant difference appeared for other pairwise comparisons (all ps > 0.056 with Holm adjustment).

The level of identification also had a significant effect, F(2, 353) = 120.79, p < 0.0001. The strongest positive association was between system justification and national identification, Zr = 0.33, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.27; 0.39], while the association was positive but weak for subgroup non-politicised identification, Zr = 0.08, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.04, 0.13]. For subgroup politicised identification, the association with system justification was negative and significant, Zr = −0.31, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.38; −0.24]. All pairwise comparisons were significant (all ps < 0.001 with Holm adjustment).

These moderators explained about 50.72% of the heterogeneity of the overall model, but the heterogeneity, although reduced, remained significant, Q(353) = 7282.59, p < 0.0001.

3.5 A Focus on Low-Status Groups

The pooled effect size (k = 166) was not significant, Zr = −0.03, SE = 0.03, t = 1.04, p = 0.298, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.03], r = −0.03. Heterogeneity was high Q(165) = 4180.85, p < 0.0001, I2 = 97.42, and especially within studies (Level 2: σ2 = 0.03, χ2[1] = 649.90, p < 0.001, I2 = 49.90) and between papers (Level 4; σ2 = 0.03, χ2[1] = 21.43, p < 0.001, I2 = 47.51), rather than between samples (Level 3: σ2< 0.001, χ2[1] < 0.001, p = 0.999, I2< 0.001) or sampling error (Level 1, I2 = 2.58). Heterogeneity suggests the potential presence of moderators. Moreover, the fact that heterogeneity was not due to sample or error in sampling suggests a more careful look at within-paper and between-study differences. One such between-study difference (i.e., moderation) relates to the specific hierarchy of the identification measures used across the studies.

3.5.1 Level of identification (Low Status)

Results showed that the social identification-system justification association was moderated by the hierarchical level of social identification, F(2, 163) = 64.47, p < 0.001 (see Figure 2c). More precisely, the positive association between social identification and system justification was strongest when national identification (k = 15) was considered, Zr = 0.31, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.21, 0.40], but it became non-significant for non-politicised subgroup identification (k = 129), Zr = −0.02, SE = 0.03, p = 0.489, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.03], and significant but negative for subgroup politicised identification (k = 22), Zr = −0.34, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.42, −0.26]. All pairwise comparisons were significant (all ps < 0.001 with Holm's correction). This moderator explained 46.30% of the heterogeneity of the overall model; accordingly, heterogeneity was highly reduced, but it was still significant (Q(163) = 1703.22, p < 0.001, I2 = 95.29).

3.6 Further Analysis on Low-Status Groups

Although the associations between politicised subgroup identification and system justification and between national identification and system justification are clear and strong, the null correlation between non-politicised subgroup identification and system justification among low-status groups invites further attention. It is entirely possible that this null effect is a true effect, and that, in fact, social identification and system justification are not associated when non-politicised identification with a low-status subgroup is considered. This would be unsupportive of both the social identity approach and SJT. Alternatively, it is possible that this null effect results from a ‘hidden’ moderator variable, capable of delineating the positive and negative associations expected under both theoretical traditions. One of the potential moderators could be system legitimacy and stability, which are taken into account by both the social identity approach and SJT. Remember that the SIMSA approach explicitly states that group behaviour is affected by the level of group identification and perceived stability and legitimacy of social hierarchy. For example, SIMSA assumes that group identification would be positively linked to system justification provided the social system is perceived as legitimate and stable in the short and long term (but see Endnote 4). Similarly, SJT theorists have argued that low-status group members would show system justification when group identification is low, especially when ‘they perceive their social systems as stable and unchanging’ (Laurin et al. 2013, 246; see also Friesen et al. 2019). To take these factors into account, we grouped different status dimensions in two ways, following Bettencourt et al.’s (2001), approach to coding the stability and legitimacy of the groups included in their meta-analysis. Bettencourt et al. instructed coders to examine ‘the introduction, method, and discussion sections of the reports, which typically yield historical, contextual, and social information relevant to the groups in question’ (526). In the case of stability coding, the authors stated that: ‘status was coded as stable if the report made it clear that the current social climate rendered it unlikely that the relative standing of the low- and high-status groups was likely to change (e.g., the relative long-standing prestige of universities; collegians vs. apprentices, doctors and social workers)’. In a similar way, the first coding we used aimed to code stability4 of social stratification and considered whether the status dimensions that were implicated in the relevant studies referred to social hierarchies that have changed or have been the subject of criticism in the last decades and compared them with those that have not changed or have not been the target of criticism/protest in the same period. For example, gender identity as a hierarchical system that favours some gender groups over others has faced severe criticism and protests (e.g., #MeToo) in recent decades. This has led to changes over time, making the gender system more unstable and often seen as less legitimate compared to the distant past (e.g., Eagly and Sczesny 2019; Valsecchi et al. 2023). Similarly, ethnic hierarchy (e.g., Storm et al. 2017) and hierarchy based on weight (e.g., Karazsia et al. 2017) have undergone changes, and are currently changing too, as evidenced by several social movements that are challenging the traditional view of ethnicity and of weight (e.g., Black Lives Matter, I can't breathe and body positive and fat rights movements). Other social hierarchies, such as social class or university hierarchy, are more stagnant and have not typically been the target of recent social turmoil and protest, which makes them relatively more enduring (i.e., unchanging) social hierarchies. To test the potential moderating effect of system changeability, we categorised studies according to whether the social identities implicated in their measure of social identification were either changing in terms of status positioning (k = 78) or unchanging (k = 50, one study was not categorised as it referred to a participants’ chosen ingroup, see Table S2 in the Supporting Information).

We also used a second coding scheme in an attempt to tap the perceived legitimacy of social stratification. Again following Bettencourt et al.’s (2001) approach to code studies based on the contextual nature of intergroup relations, we considered different social hierarchies in terms of whether or not they referred to a social stratification that is deserved (e.g., based on meritocracy) or ascribed (i.e., with no objective means of determining the deservingness of status differences, k = 87). For example, the gender identity (as a hierarchical system) is based on whether an individual is assigned to the male or female sex categories at birth, which is an arbitrary set-based system (Sidanius and Pratto 1999) as it lacks any objective metric for choosing males over females as being the superior sex. The same principles apply with respect to ethnic/racial hierarchies that depend on whether one is born, for example, Black or White. It is precisely due to the absence of an objective means of determining those at the top and bottom that such conditions should theoretically intensify concerns about whether the existing social stratification is justified. Hence, we identified and coded group contexts in which stratifications could be seen as being more objectively derived (k = 41, again, one study was not categorised as it referred to participants’ chosen ingroups). In the case of socio-economic background, for example, glaring income/asset statements can be used to determine those on the Forbes list of richest people (i.e., extremely rich), and those who do not make this elite camp. A similar logic applies to the context of university ranking, where research and teaching performance are used to determine institutions that are usually at the top of university league tables and those at the bottom. This latter more objective context is theoretically able to instil a sense of legitimacy in the prevailing social stratifications, which perhaps explains why members of objectively low-status groups largely tend to legitimise prevailing systems (Jost et al. 2003; Li et al. 2020; Owuamalam et al. 2024), while members of subjectively lower status groups largely tend to perceive the existing order as illegitimate (Brandt et al. 2020). For both coding schemes, we asked three independent judges, who are themselves social psychologists but unaware of the research purposes, to categorise the relevant systems across the papers we analysed to fit the definitions of two constructs. For both changing/unchanging and objective/subjective dimensions inter-rated agreement with our own coding was good (Krippendorf's alpha = 0.82 and 0.96, respectively) with 84% and 96% levels of agreement, respectively.

Thus, in two subsequent analyses, we tested whether the changeability of social stratification (changing vs. unchanging hierarchies) and the perceived legitimacy of social stratification (objective vs. arbitrary social hierarchies) would moderate the null relationship between subgroup non-politicised identification and system justification among low-status groups.

3.6.1 Changeability of Social Stratification

Results (see Figure 2c) revealed a significant moderation effect for the association between non-political subgroup identification and system justification among low-status groups (F(1, 126) = 6.47, p = 0.012, I2 = 88.01). More precisely, the identification-system justification relationship was negative (although non-significant) when the low-status identity in question has undergone changes over time (i.e., when the stability of social stratification in question was lower), Zr = −0.03, SE = 0.03, p = 0.232, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.02]. Meanwhile, the association between non-political subgroup identification and system justification was positive (and statistically significant) when the low-status identity in question was relatively unchanging (i.e., when the stability of social stratification being considered was higher) over time, Zr = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = 0.036, 95% CI [0.01, 0.21].

3.6.2 Perceived Legitimacy of Social Stratification

Also in this case, results (see Figure 2c) revealed a significant moderation effect on the association between non-political subgroup identification and system justification (F(1, 126) = 6.36, p = 0.013, I2 = 88.13). The identification-system justification relationship was negative (although non-significant) when the low-status identity in question may be seen as arbitrarily ascribed (i.e., when a less legitimate status dimension was considered), Zr = −0.03, SE = 0.03, p = 0.264, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.02]. The association between non-political subgroup identification and system justification was instead positive and statistically significant when the low-status identity in question may be seen as objectively achieved (e.g., more legitimate), Zr = 0.14, SE = 0.06, p = 0.028, 95% CI [0.02, 0.26].

3.7 Sensitivity Analysis

For the whole dataset, the analysis revealed that the overall effect size change was small (range = 0.10 to 0.12) when each single study was excluded from the analysis. Moreover, we identified 30 influential observations based on one or more of the indicators that we considered. When these cases were excluded one at a time, meta-analytical results yielded similar results as the analysis in which extreme cases were not excluded, all Zr ranged from 0.10 to 0.12, 95% CI [0.05–0.16; 0.07–0.17], and the difference of variance at Levels 2, 3 and 4 was low (Level 2: σ2 = 0.03–0.04; Level 3: σ2< 0.0001–< 0.0001; Level 4: σ2 = 0.04–0.05).

For meta-analysis of low-status groups, again, our sensitivity analysis revealed that the pooled effect size had little change when each single study was excluded from the analysis (range Zr = −0.04 to −0.02). We detected 9 extreme cases. Also in this case, exclusion of these cases did not change the general results, as all Zr ranged from −0.04 to −0.02, 95% CI [−0.10; 0.02; −0.07; 0.04] and the difference of variance at Levels 2, 3 and 4 was low (Level 2: σ2 = 0.03–0.03; Level 3: σ2< 0.0001–< 0.0001; Level 4: σ2 = 0.02–0.04).

3.8 Publication Bias and Power

For the whole sample of studies, there was no significant effect when either the standard error, b = −0.21, SE = 0.36, t = 0.58, p = 0.560, 95% CI [−0.93, 0.50], or the reciprocal of the sample size, b = −1.08, SE = 1.77 t = 0.61, p = 0.540, 95% CI [−4.56, 2.39] were added as predictors. Similarly, in the low-status groups subset, there was no significant effect due to the standard error, b = 0.34, SE = 0.54, t = 0.63, p = 0.533, 95% CI [−0.72, 1.40], or the reciprocal of the sample size, b = 0.49, SE = 2.53, t = 0.19, p = 0.846, 95% CI [−4.51, 5.49].

The p-curve analysis revealed a right-skew (p < 0.001), indicating that a ‘true’ effect was likely to be present in our data, and not flat (p = 0.999), indicating that power was sufficient. Accordingly, the observed power was 99% CI [99%, 99%]. Similarly, Z-curve analysis revealed an ERR of 0.85. Similar results were obtained for a p-curve and Z-curve analysis of the low-status group subset analysis, where the observed power was 99% with 95% CI = [99%, 99%], with an ERR of 0.80.

4 Discussion

Is social identification positively or negatively associated with system justification, especially amongst members of disadvantaged groups? This question lies at the heart of the ongoing debate between two prominent perspectives on system justification: system justification theory (SJT, Jost et al. 2019) and the SIMSA (Owuamalam et al. 2019a) because it speaks to the necessity of a unique system motive that operates independently of personal and group interests. SJT assumes that system justification serves a different function for people beyond personal and group motives so that amongst the disadvantaged, group and system motives are by and large incompatible. SIMSA, on the other hand, assumes that system justification can be compatible with group-based motives, which is why it tends to predict a positive association between group identification and system justification. SIMSA only predicts a negative association between subordinate identification and system justification when the need for social accuracy is salient, and, in this case, it also predicts a positive association between superordinate identification and system justification.

The literature on system justification has recorded mixed evidence for the association between social identification and system justification: Sometimes the relationship is negative, sometimes it is positive, and at other times it is null. This mixed evidence further compounds a quarter-century-long spat between the SJT and SIT camps, with the resolution requiring a multiplicity of approaches, including a meta-analytical synthesis of the available evidence. In our meta-analysis, therefore, we synthesised the published and unpublished data on this crucial association and considered relevant moderators separating SJT's predictions from SIMSA's. We would like to stress once more that our aim was not to provide a test of the superiority of one theory over another, nor to definitively resolve the various points of contention in the debate between SJT and SIMSA researchers. Rather, our goal was to determine which direction the relationship between social identification and system justification leans, overall, based on the accumulated evidence thus far, and to observe when and how this relationship changes as a function of specific theoretically relevant moderators. Table 1 summarises the key findings, how they align with the theoretical frameworks, and what this reveals about the overall direction of the relationship between social identification and system justification, along with their broader implications.

| Outcome of confirmatory predictions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analytical evidence | Is it congruent with SIMSA/SIT? | Is it congruent with SJT? | General theoretical implication |

| The association between social identification and system justification (ID-SJ) is stronger and positive for high-status groups [Prediction 1] | Yes. Privileged groups are motivated to justify systems that they benefit from more so than their underprivileged counterparts | Yes. For the same reason suggested by SIT | Social advantage makes it more likely that group interests positively align with systems responsible for this privilege |

| ID-SJ association is significant and positive for intermediate-status groups [Prediction 1] | Yes. The hypothesis that system justification is linked to identification with a disadvantaged group capable of making positive downward comparisons is supported | Not entirely. SJT does not directly address intermediate-status groups. However, the general hypothesis that system and group justifications are inversely related in disadvantaged groups is not fully supported | Group and system interests are compatible among relatively disadvantaged groups that can engage in positive downward comparisons |

| ID-SJ association is positive but weak for non-politicised subgroup identities [Prediction 1] | Yes. The hypothesis that system justification is positively associated with group interests is supported | No. The expectation that system justification and subgroup identification should be either negative or uncorrelated is not supported | Interests tied to membership of non-politicised groups are often compatible with interests linked to prevailing social arrangements |

| ID-SJ association is null for non-politicised low-status groups [Prediction 1] | Not entirely. The specific hypothesis that system justification and ingroup identification are positively correlated among low-status groups, without considering the legitimacy, stability or group-type caveats is not supported | No. The hypothesis that system justification and subgroup identification are negatively correlated among low-status groups is not supported | The interests of low-status groups are not always directly correlated with system interests |

| ID-SJ association is negative when politicised identities are considered, even among low-status groups [Prediction 2] | Yes. The hypothesis that members of low-status groups with identities that have become politicised resist and/or contest oppressive systems is supported | Yes. The hypothesis that groups engaged in political struggle exhibit low system justification is supported | For groups engaged in political struggle, ingroup identification and perceptions of system legitimacy are inversely correlated |

| ID-SJ association is positive when national identities are considered, even among low-status groups [Prediction 3] | Yes. The hypothesis that system justification functions as an ingroup bias at the overarching superordinate level is supported | Not entirely. While the relationship between system justification and national identification is not explicitly theorised, it is acknowledged in certain cases. This recognition exists despite the argument that system and group-related interests are typically either independent or inversely related among disadvantaged groups | A sense of belonging to an inclusive social system is often closely associated with system justification |

| Outcome of exploratory predictions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analytical evidence | Is it congruent with SIMSA/SIT? | Is it congruent with SJT? | General theoretical implication |

| The overall association between social identification and system justification is positive but small | Yes. The hypothesis that group identities/interests and system interests are compatible rather than antagonistic to one-another is supported | Not entirely. The hypothesis that system justification is separable from group justification is not fully supported | System justification is more often than not associated with ingroup identities/interests |

| ID-SJ association among low-status groups is positive when status differences are perceived as stable or legitimate but null when they are seen as unstable or illegitimate | Yes. The hypothesis that, among low-status groups, system justification and ingroup identification are positively correlated when status differences are viewed as legitimate or stable is supported | No. The hypothesis that low-status group members show system justification when group identification is low, especially when they perceive their social systems as stable and unchanging is not supported | The perceived legitimacy and stability of a system is crucial in shaping low-status group members’ positive attitudes towards the prevailing order |

4.1 The Current Findings

Our meta-analytical synthesis provides evidence that overall, the association between social identification (i.e., whether it be at the subgroup or superordinate levels) and system justification is positive (even if small according to Funder and Ozer's 2019) criteria. This suggests, first and foremost, that system justification can be compatible with group-based motives. When we unpacked this association with respect to the hierarchical level of social identification the evidence showed (a) a large negative association when it comes to politicised subordinate group identification and system justification, consistent with both SJT and SIT, (b) a small positive association between non-politicised subordinate identification and system justification, consistent with SIMSA but not SJT, and (c) a large association between superordinate group identification and system justification, also clearly consistent with SIMSA but less with SJT. With regard to this last finding, we note that system justification theorists seem to have conceded that system justification may be positively associated with superordinate group identification (Jost et al. 2023). However, it is also important to note that this speculation is not in the original statements of SJT (see Jost and Banaji 1994; Jost et al. 2003; Jost et al. 2004), and it may require further clarification. As Rubin et al. (2023a, 22) have pointed out, if SJT predicts a positive association between superordinate identification and system justification among the disadvantaged, then it is unclear how it rules out SIMSA's group-based explanations for system justification in this case. In other words, our finding that superordinate identification and system justification are consistently and positively correlated makes it harder to exclude group motives as an additional explanation of system justification among low-status groups.

We discuss the divergent results for the different hierarchical levels of identification later, but first we would like to emphasise that the critical overall positive (though small) association between social identification and system justification was present only for high-status and intermediately (dis)advantaged groups but absent for low-status groups (i.e., null).

4.2 Suggestions, Clarifications and Open Questions

4.2.1 High Status Groups

As we have stated elsewhere in this paper, it is possible to claim that a positive association between social identification and system justification is not only supportive of the social identity approach but also SJT. The argument is that justification of systems that confer privileges to one's group among those who are most strongly invested in their group's privilege is unsurprising because it should be straightforward in this context to embrace the status quo unreservedly: a point that even SJT's critics have conceded in the past (e.g., Owuamalam et al. 2019a; Rubin et al. 2023a). But, it is difficult to reconcile this argument with the proposal of a separate system justification motive that operates independently of group motives. As Jost and Banaji (1994, 10) emphasised, ‘system justification does not offer an equivalent function that operates in the service of protecting the interests of the self or the group’. A positive association between group identification and system justification for high-status groups suggests that group-based motives may be the drivers of system justification rather than a separate system motive that operates outside of group interest. In other words, the fact that the meta-analytical evidence points to a reliable positive association indicates that among high-status group members, system justification is tied to social identity needs. This makes the SJT idea that a unique system motivation is the main operational principle in this context less compelling, compared to the more parsimonious insight offered by the SIMSA model (and the social identity tradition more broadly), which suggests that members of high-status groups tend to justify systems that confer a positive social identity, especially when they are strongly invested in that identity.

4.2.2 Low-Status Groups

The evidence that politicised subgroup identification is strongly negatively associated with system justification amongst the disadvantaged ostensibly support both SJT and the broader social identity approach. Indeed, especially for SJT, disadvantaged groups that are deeply entrenched in political struggle (e.g., male, female and gender non-conforming individuals embracing a feminist identity) are the ideological context in which the motivation to justify the status quo comes in sharp opposition with the motivation to enhance group identity, potentially generating a level of dissonance that is then resolved by embracing the status-quo rather than pursuing a potentially uphill battle for social change. The difficulty with this dissonance explanation, as Owuamalam et al. (2016) have pointed out, is that a dissonance-induced system justification ought to be most visible when group identification is strong, not when it is weak.

There is a simpler explanation rooted in the social identity tradition. Group identities that are characterised by political struggle seem unlikely to be a context in which legitimacy perceptions are at their highest. Therefore, the potentially high illegitimacy perceptions in group identities characterised by political struggle could create a strong need for resistance that may explain the negative association between group identification and system justification. Opposition to disadvantageous systems is a behavior that is often associated with people who are strongly invested in the relevant identity (van Zomeren et al. 2008). In short, the classic SIT (Tajfel and Turner 1979) seems to have an upper hand in this context because its prediction of a negative association between social identification and system justification explicitly assumes illegitimate situations (which group identities characterised by political struggle fulfil).

Is a negative association between politicised group identification and system justification unsupportive of SIMSA since it tends to predict a positive association between subordinate group identification and system justification (i.e., in the absence of concerns about social accuracy; see Table 2 in Rubin et al. 2023a)? Probably not. There is no inconsistency here because, again, SIMSA's prediction of a largely positive association between social identification and system justification is only applicable in the context of a legitimate social order, and politicised identity groups are unlikely to satisfy this requirement. In short, the negative association between politicised identification and system justification when social stratification is appraised as illegitimate is a common denominator between SIMSA, SIT and SJT, only that in the latter case (i.e., SJT), its dissonance-based explanation for it seems to be at odds with what proponents of cognitive dissonance theory envisaged.

In contrast to politicised identification, a non-politicised identity should elicit fewer illegitimacy concerns, and this is a context in which SIMSA would predict the most positive association between social identification and system justification among the disadvantaged, with SJT predicting a negative association. Our results are in favour of SIMSA here, in that among low-status groups, the association between subgroup non-politicised identification and system justification was positive (albeit small), particularly when unchanging (i.e., more stable) and objective (i.e., more legitimate) social hierarchies were considered. In other words, identification with disadvantaged subgroups is positively and significantly correlated with the justification of stable and legitimate systems while it is not different from zero when justification refers to unstable or less legitimate systems.

4.2.3 Intermediately (Dis)Advantaged Groups

Often overlooked in the debate between SJT and SIMSA is what the association between social identification and system justification could look like amongst intermediately (dis)advantaged groups. This instance represents a situation in which members are likely to hold system attitudes that mirror either those of high-status groups (because a downward comparison that pits them against groups that are even lower in the food chain is possible; e.g., Caricati 2018; Caricati et al. 2020) or low-status group (because an unfavourable upward comparison with higher status outgroups is possible; e.g., Vanneman and Pettigrew 1972). In the current analysis, we found an overall positive association between social identification and system justification for this group, indicating that their system attitudes mirror those of the advantaged. It is possible to claim that SJT could explain this evidence because the theory assumes that groups that are advantaged in the system ought to support it since doing so does not undermine their personal/group interests. But, like we argued earlier, this evidence does not provide support for the existence of a unique system motive that is independent of social identity needs—a cornerstone of the system justification perspective. Hence, the evidence seems more supportive of SIMSA's group-interested explanations for system justification of both advantaged and disadvantaged groups, stating that ‘the need for a positively distinct social identity motivated perceptions of system legitimacy in the intermediate status condition’ (Rubin et al. 2023a, 215).

4.3 Caveats

Before concluding, it is important to stress that we tried to consider several sources of variability (or dependence) among effect sizes other than sampling and between-study errors. We discovered that, in the pool of samples we analysed, the variance was primarily due to both different measurements in the same sample and different papers (where studies were nested) more than the difference within the samples that were considered. In other words, results from different samples coming from the same papers have fewer variance than results from different papers. Although this finding seems less informative on the surface, it supplies a valuable piece of evidence on which to suppose that the association between system justification and social identification is highly variable depending on different contextual and methodological artefacts. Nevertheless, taking these sources of variability (or dependence) into account seemed to increase (not undermine) the precision/reliability of our results.

4.4 Limitations

This paper has several limitations that need to be addressed. First, it is largely based on correlational evidence, preventing us from making causal linkages between constructs. Another limitation lies in the categorisation of social systems as changeable/unchangeable and objective/subjective. These categorisations were made by the researchers in an effort to better understand the null relationship between social identification and system justification among apolitical groups. However, it is important to note that our categorisations of legitimacy and stability do not reflect how participants in the studies included in our meta-analysis themselves perceived the stability or legitimacy of social stratification. This introduces a degree of interpretational ambiguity, particularly given that, as one reviewer noted, research within the SIT tradition has typically manipulated legitimacy and stability as orthogonal constructs in experimental settings (e.g., Turner and Brown, 1978; Ellemers et al. 1993). Nonetheless, there is at least one reason for following Bettencourt et al.’s approach to operationalising these constructs in the current analysis. While laboratory studies have demonstrated that legitimacy and stability can be empirically separated, they are often correlated in real-world contexts. For instance, Vaughan's (1978) longitudinal research on changing status dynamics between the Māori and Pākehā in New Zealand found that social stratification became unstable when seen as illegitimate—and vice versa. This natural co-dependence is also acknowledged by Tajfel (1981), the key proponent of SIT, who observed that ‘an unstable system of social divisions between groups is more likely to be perceived as illegitimate than a stable one; and conversely, a system perceived as illegitimate will contain the seeds of instability’ (250). While lab-based studies often aim to isolate the independent and interactive effects of legitimacy and stability, our aim was somewhat different: to examine the relationship between social identification and system justification using measures that reflect how legitimacy and stability manifest together in real-world settings, thereby enhancing ecological validity. In doing so, we treated these constructs as naturally covarying—akin to assessing their co-dependent or ‘total effect’ rather than their isolated ‘direct effects’. Still, future experimental research should seek to disentangle their individual contributions to better understand their distinct roles.

Furthermore, we adopted a binary coding approach that does not consider that the stability/instability of social hierarchy is rarely permanent and can fluctuate over time. Hence, our coding is time-dependent and applies only to the period from the paper's publication to the coding date. Similarly, our binary coding of deserved versus arbitrary social hierarchy does not consider that individuals and groups may differ in their interpretation of the nature of social hierarchy (i.e., if deserved or arbitrary). Again, this might limit the precision and generalisability of our results that only a carefully controlled experiment (which we recommend) can unpack. A further limitation refers to the use of politicised subgroup identity. Although our coding was congruent with the conceptualisation of politicised identity as overtly critical against existing social hierarchies, we were not able to distinguish the content of such politicised identity (e.g., progressivist, reactionary, anti-establishment, etc.). These and other similar methodological issues are unfortunate aspects of adopting a meta-analytical approach that curtails the researchers’ ability to offer a controlled manipulation of key variables, relying only on existing secondary data that contain imperfections from the original studies.

5 Concluding Remarks

We set out to determine whether the overall association between social identification and system justification tends to lean in the positive or negative direction—particularly among disadvantaged groups—in order to inform a long-standing debate, now spanning over 25 years, between two major theoretical traditions in social and political psychology: SJT and the SIMSA. Consistent with SIMSA, the results revealed a mostly positive association between social identification and system justification. This positive association, for the disadvantaged at least, emerged under the enabling conditions specified in SIMSA: that is, it occurred when non-politicised identification was considered, provided the social stratification in question fulfilled the necessary conditions of being a stable and legitimate order. Outside of these conditions (e.g., when politicised identities were considered, making system illegitimacy salient), there seemed to be a largely negative association between group identification and system justification amongst the disadvantaged, consistent with both SJT and SIMSA. Notably, neither theoretical framework consistently accounted for all patterns in our meta-analytic findings. This highlights the need for both SJT and SIMSA to evolve—through refinement and integration—if they are to offer more precise and comprehensive predictions about how social identification shapes attitudes towards the system.

Acknowledgement

Open access publishing facilitated by Universita degli Studi di Parma, as part of the Wiley - CRUI-CARE agreement.

Ethics Statement

No original data were collected; therefore, this project did not undergo review by the Institutional Review Board approval. There was also no informed consent due to the nature of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/68k4n/?view_only=21d4cd1225fd4d49a72327c1422a4d25.