Impact of mental disorders on unplanned readmissions for congestive heart failure patients: a population-level study

Abstract

Aims

Reducing preventable hospitalization for congestive heart failure (CHF) patients is a challenge for health systems worldwide. CHF patients who also have a recent or ongoing mental disorder may have worse health outcomes compared with CHF patients with no mental disorders. This study examined the impact of mental disorders on 28 day unplanned readmissions of CHF patients.

Methods and results

This retrospective cohort study used population-level linked public and private hospitalization and death data of adults aged ≥18 years who had a CHF admission in New South Wales, Australia, between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2020. Individuals' mental disorder diagnosis and Charlson comorbidity and hospital frailty index scores were derived from admission records. Competing risk and cause-specific risk analyses were conducted to examine the impact of having a mental disorder diagnosis on all-cause hospital readmission. Of the 65 861 adults with index CHF admission discharged alive (mean age: 78.6 ± 12.1; 48% female), 19.2% (12 675) had at least one unplanned readmission within 28 days following discharge. Adults with CHF with a mental disorder diagnosis within 12 months had a higher risk of 28 day all-cause unplanned readmission [hazard ratio (HR): 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.15–1.27, P-value < 0.001], particularly those with anxiety disorder (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.35–1.65, P-value < 0.001). CHF patients aged ≥85 years (HR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.11–1.28), having ≥3 other comorbidities (HR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.25–1.46), and having an intermediate (HR: 1.34, 95% CI: 1.28–1.40) or high (HR: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.27–1.47) frailty score on admission had a higher risk of unplanned readmission. CHF patients with a mental disorder who have ≥3 other comorbidities and an intermediate frailty score had the highest probability of unplanned readmission (29.84%, 95% CI: 24.68–35.73%) after considering other patient-level factors and competing events.

Conclusions

CHF patients who had a mental disorder diagnosis in the past 12 months are more likely to be readmitted compared with those without a mental disorder diagnosis. CHF patients with frailty and a mental disorder have the highest probability of readmission. Addressing mental health care services in CHF patient's discharge plan could potentially assist reduce unplanned readmissions.

Introduction

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is one of the major health issues in high-income nations. In 2019, it was estimated that there were around 56.19 million cases globally, resulting in 5.05 million years lived with disability across the world.1 In the United States, the cost of heart failure was estimated to be US$30.7 billion in 2012 and projected to rise to US$69.8 billion by 2030, with hospitalization being the major contributor.2 In Australia, the Australian National Health Survey estimated that over 102 000 people had heart failure in 2017–183 and around 1.5% of all hospitalizations in Australia could be attributed to heart failure in 2020–21.3 As one of the 22 conditions recognized for which hospitalization is potentially preventable,4 CHF has been listed as a national health priority since 1997,5 and the readmission rate related to CHF has been a clinical indicator regarding health system performance in New South Wales (NSW) for more than 10 years.6 Despite advances in the management of CHF, readmission rates, especially unplanned readmissions, are still relatively high and continue to be a significant challenge for healthcare systems. In NSW, the average 30 day readmission rate for CHF has been the second highest of all conditions, at around 22 readmissions per 100 hospitalizations or 37%.6

Adults with CHF often have comorbid conditions. Mental and behavioural conditions, such as dementia, depression, and anxiety, are common comorbid health conditions in people with CHF.7-9 The prevalence of depression in CHF patients was estimated between 20% and 30%, with around 20% meeting depressive diagnosis criteria, based on interviews.9 A meta-analysis conducted in 2016 estimated that nearly 30% of individuals with CHF experience clinically significant anxiety symptoms, with around 13% meeting the criteria for anxiety disorders.10 In a study by Cannon et al., cognitive impairment was found in 43% of adults with heart failure.11 Although depression and dementia have been linked to an increased all-cause mortality rate,9, 12 evidence of the impact of some mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorder, on health outcomes for CHF patients has not been clarified.7, 8

One reason why mental health conditions have not been extensively examined for patients with CHF may be because comorbidity indices that are commonly used as a covariate in the examination of predictors of hospital readmission, such as Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices, include very few mental and behavioural disorders.13, 14 As such, mental and behavioural comorbidities are not commonly identified in studies of risk factors for CHF readmission.15-18 Understanding the impact of mental disorders on readmissions amongst adults experiencing CHF is crucial for developing evidence-based and effective interventions to reduce the disease burden on both individuals with CHF and the health system. This study examined the impact of mental disorder on 28 day unplanned readmission of CHF patients.

Methods

Data sources and linkage

This study used data from the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC), which provides a comprehensive census of all hospital admissions, both public and private, in NSW. The APDC includes administrative information on episodes of care, such as start and end dates, as well as up to 51 detailed diagnosis and procedure codes, which are classified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM), and Australian-Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups. APDC data were extracted for the period 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2021.

The hospital admission records were linked to the death registrations (fact of death) from the NSW Registry of Birth, Deaths and Marriages (1 January 2014 to 30 June 2022) and Cause of Death Unit Record File (1 January 2014 to 31 December 2020). Record linkage was conducted by NSW Health's Centre for Health Record Linkage (www.CHeReL.org.au) using probabilistic matching.

Ethics approval and a waiver of consent were obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number 2022/ETH00861).

Study design and study population

This was a retrospective cohort analysis that used hospital admission records to identify adults aged ≥18 years who had at least one hospital admission with a principal diagnosis of either heart failure (ICD-10-AM code I50) or hypertensive heart disease (I11, I13.0, and I13.2) between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2020. Although it is suggested that all additional diagnosis codes should be included for estimating heart failure's contribution to hospitalization,3 this study only used the principal diagnosis to identify the index admission, so as to limit the treatment variations and confounding factors during the index admission.

This study excluded any episode of care provided in a public inpatient aged care facility. Logic checks were performed to identify any records with errors (e.g. admission post-death). All admission records related to patients with logic errors were removed. All hospital episodes of care related to the same admission were associated and grouped into a period of hospital care (PoHC). Deaths during the index admission were excluded from analysis. The initial CHF hospital admission during the study period was designated as the ‘index admission’ for each patient, and subsequent all-cause readmissions were identified based on the index admission. Index admission length of stay (LOS) and readmission LOS were calculated according to each PoHC. Residents of aged care facilities at the index admission were identified using referral source, discharge information, and financial class in the APDC.

The Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) of Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas was assigned based on the individual's residential address. IRSD was estimated by Australian Bureau of Statistics using census data and takes into consideration social and economic factors related to people and households, such as household income, employment, and education level, in an area.19 Urban or rural status was aggregated from the remoteness classes based on residential address using Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) 2016. The ASGS reflects road distance to service centres of different sizes,20 and the ASGS was aggregated into urban (i.e. major cities) and rural (i.e. inner, outer regional, and remote and very remote areas).

Identification of comorbidities and frailty risk

Comorbidities were identified using up to 51 diagnosis classifications in the APDC. A 12 month lookback period with inclusion of the index admission was used for the hospital admission records to ascertain the conditions. Mental and behavioural disorders were identified according to ICD-10-AM Chapter V. Anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders were identified using corresponding ICD-10-AM codes in the same chapter, and dementia was identified by including two additional codes (G30 and G31).

The number of comorbidities was calculated based on conditions identified according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index using the same diagnosis classification in the APDC.14 CHF (ICD-10-AM: I50) and dementia were excluded from the count of comorbidities. The number of comorbidities was categorized as nil, 1–2, and ≥3 comorbidities. Indicators for acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary disease, diabetes, and renal disease were identified separately using the definitions from Charlson Comorbidity Index due to clinical relevance to CHF. Obesity, past and current smoking status, alcohol dependency or abuse, and substance dependency or abuse were identified separately using corresponding ICD-10-AM codes within the lookback period (Appendix 1).

The validated Hospital Frailty Risk Score21 was used to calculate the frailty risk. Each of the 109 ICD-10-AM diagnosis or external cause codes was assigned a score ranging from 0.1 to 7.1 based on its frailty characteristics. Dementia and depression as conditions of interest were excluded from the final score. The score for an individual was calculated using the diagnosis classifications from the APDC during the same 12 month lookback period. Frailty risk was categorized as low (<5), intermediate (5–15), or high (>15) based on the calculated score.

Hospital readmission and mortality

Hospital readmissions for any cause were identified for the cohort within 28 days following discharge from an index admission, including both public and private hospitals. Acute and emergency readmissions were identified as unplanned readmissions. If more than one readmission occurred within the study period, only the first readmission was considered as the event of interest. Only admissions outside of the index admission's PoHC were considered as readmissions. All deaths were identified using linked death registrations.

Data management and analysis

Data management was carried out using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.), and data analysis was performed using R Version 4.2.2 with packages survival (3.5-3) and flexsurv (2.2.2). Crude number and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. For continuous variables, median and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated. The χ2 test of independence and the Wilcoxon rank sum test or the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test were used to determine differences between demographic characteristics by readmission type or death without readmission.

To accurately assess risk of, and time to, unplanned readmission, both deaths and planned readmissions were considered as competing risks in a multi-states parametric time-to-event regression mixture model. Distributions for each state were chosen using the Grambsch, Therneau, and Fleming plot.22 Using this model, the probability that an individual would experience each event before the other, and the time to the event conditional on that event occurring first, was calculated, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) estimated using bootstrap-like simulation with 500 samples. Preliminary testing demonstrated that increasing the number of samples beyond 500 did not significantly improve the precision of the CI estimates. As a competing risk model is prone to misspecification for covariate effects,23 cause-specific log-logistic time-to-event regression models were built to evaluate the effect of mental disorders on unplanned readmissions. Variables previously identified as associated with hospital readmission15, 17, 18, 24 and available in the data were assessed for modelling. In considering the potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions, admissions with COVID-19 diagnosis were identified, and an indicator variable was added to identify episodes from the start of the first COVID-19 cases recorded in NSW (13 January 2020).25 Univariate log-logistic time-to-event regression was used to assess factors for the model first; those that did not significantly contribute to risk of unplanned readmission at P < 0.1 were excluded. A backward modelling approach was used to build the multivariable cause-specific models with only variables with P ≤ 0.05 were retained. The final multivariable cause-specific modelling included age group, sex, Aboriginality (Y/N), number of comorbidities (i.e. nil, 1–2, and ≥3), frailty risk (i.e. low, intermediate, and high), urban or rural status, diagnosis of mental disorders (Y/N) (or breakdown in different mental disorders), acute myocardial infarction (Y/N), renal disease (Y/N), pulmonary disease (Y/N), alcohol and substance abuse (Y/N), and index admission discharge facility (coded facility identifier). Due to statistical power limitation, only variables that had the strongest contribution to cause-specific models were used for competing risk models. The final multivariable competing risk model included Aboriginality (Y/N), number of comorbidities (i.e. nil, 1–2, and ≥3), frailty risk (i.e. low, intermediate, and high), and diagnosis of mental disorders (Y/N) (or breakdown in different mental disorders).

Results

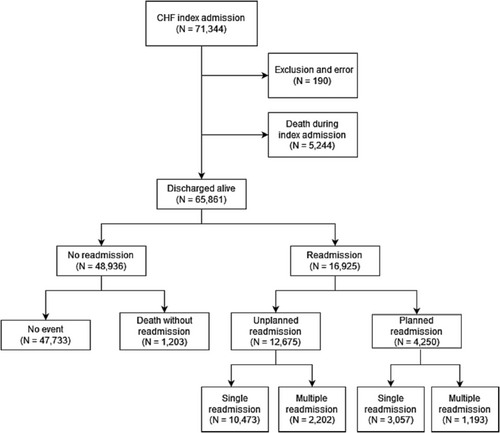

There were 71 154 adults who had at least one CHF admission between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2020, and 5244 (7.4%) died during the index admission. Of the 65 861 adults discharged alive, 25.7% (16 925) had at least one all-cause readmission, and 19.2% (12 675) had at least one unplanned readmission within 28 days following discharge. In the 16 925 adults with a readmission, 3395 (20.1%) had more than one readmission during the 28 day follow-up period, with 2202 adults (17.4%) having additional readmission(s) after an unplanned readmission and 1193 (28.1%) after having a planned readmission. Of the 48 936 adults without readmission, 2.5% died during the follow-up period (Figure 1). There were no adults with CHF during the index admission or follow-up period that had admission with a COVID-19 diagnosis.

The mean age in this study was 78.6 (SD 12.1) years at the time of the index admission. Adults who died without readmission were older (64.8% ≥ 85 years) compared with adults who had an unplanned (37.3% ≥ 85 years), planned (26.6% ≥ 85 years), or no (35.1% ≥ 85 years) readmission. Older males with intermediate or high frailty scores, who had ≥3 other comorbidities, and who were diagnosed with a mental disorder had a higher likelihood of experiencing an unplanned readmission within 28 days. Amongst individuals who died without a readmission, around 31.0% were residents of aged care facilities and 26.3% had high frailty. A higher proportion (27.8%) of unplanned readmissions were of adults who had a mental disorder diagnosis compared with 20.8% of those who were not readmitted or did not die (i.e. no events) and 18.3% of those who had a planned admission. Around 5.5% of adults who had an unplanned readmission had an anxiety disorder diagnosis compared with 3.3% of adults with no readmission or death and 4.0% of adults who had a planned admission (Table 1).

| Characteristic | No event | Unplanned readmission | Planned readmission | Death without readmission |

χ2 (df) P-value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 47 733 | n = 12 675 | n = 4250 | n = 1203 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age group | 712.5 (9)*** | ||||||||

| 18–64 | 6174 | 12.9 | 1486 | 11.7 | 719 | 16.9 | 44 | 3.7 | |

| 65–74 | 8971 | 18.8 | 2225 | 17.6 | 948 | 22.3 | 71 | 5.9 | |

| 75–84 | 15 815 | 33.1 | 4241 | 33.5 | 1452 | 34.2 | 308 | 25.6 | |

| ≥85 | 16 773 | 35.1 | 4723 | 37.3 | 1131 | 26.6 | 780 | 64.8 | |

| Sex | 118.5 (3)*** | ||||||||

| Male | 24 769 | 51.9 | 6751 | 53.3 | 2565 | 60.4 | 597 | 49.6 | |

| Female | 22 964 | 48.1 | 5924 | 46.7 | 1685 | 39.6 | 606 | 50.4 | |

| Index admission LOS (days)a | 5 (3, 10) | 6 (3, 11) | 5 (2, 11) | 9 (4, 19) | 283.5 (3)*** | ||||

| Index admission ICU stay | 1745 | 3.7 | 483 | 3.8 | 279 | 6.6 | 33 | 2.7 | 93.3 (3)*** |

| First readmission LOS (days)a | — | 5 (2, 11) | 1 (1, 4) | — | 1866.8 (1)*** | ||||

| Total days in hospital during follow-up perioda | — | 7 (3, 16) | 3 (1, 10) | — | 904.9 (1)*** | ||||

| Aged care resident | 2569 | 5.4 | 587 | 4.6 | 89 | 2.1 | 373 | 31.0 | 1622.1 (3)*** |

| Urban/ruralb | 39.7 (3)*** | ||||||||

| Urban | 32 109 | 68.4 | 8822 | 70.1 | 2822 | 67.2 | 747 | 62.3 | |

| Rural | 14 834 | 31.6 | 3762 | 29.9 | 1376 | 32.8 | 452 | 37.7 | |

| SEIFA IRSD quintilec | 186.4 (12)*** | ||||||||

| 1 (most disadvantaged) | 12 029 | 25.6 | 3437 | 27.3 | 891 | 21.2 | 274 | 22.9 | |

| 2 | 12 219 | 26.0 | 3287 | 26.1 | 1048 | 25.0 | 360 | 30.0 | |

| 3 | 9219 | 19.6 | 2441 | 19.4 | 750 | 17.9 | 208 | 17.3 | |

| 4 | 5818 | 12.4 | 1550 | 12.3 | 566 | 13.5 | 167 | 13.9 | |

| 5 | 7652 | 16.3 | 1869 | 14.9 | 943 | 22.5 | 190 | 15.8 | |

| Number of comorbiditiesd | 721.5 (6)*** | ||||||||

| Nil | 16 716 | 35.0 | 3276 | 25.8 | 1274 | 30 | 336 | 27.9 | |

| 1–2 | 23 162 | 48.5 | 6237 | 49.2 | 2031 | 47.8 | 577 | 48.0 | |

| ≥3 | 7855 | 16.5 | 3162 | 24.9 | 945 | 22.2 | 290 | 24.1 | |

| Frailty scored | 1075.6 (6)*** | ||||||||

| Low | 26 389 | 55.3 | 5454 | 43 | 2175 | 51.2 | 310 | 25.8 | |

| Intermediate | 16 455 | 34.5 | 5434 | 42.9 | 1643 | 38.7 | 577 | 48.0 | |

| High | 4889 | 10.2 | 1787 | 14.1 | 432 | 10.2 | 316 | 26.3 | |

| Obesity | 6955 | 14.6 | 1818 | 14.3 | 668 | 15.7 | 93 | 7.7 | 50.0 (3)*** |

| Smoking (past and current) | 21 106 | 44.2 | 6041 | 47.7 | 2102 | 49.5 | 419 | 34.8 | 132.4 (3)*** |

| Mental health and behavioural disorders | 9924 | 20.8 | 3525 | 27.8 | 778 | 18.3 | 492 | 40.9 | 563.2 (3)*** |

| Dementia | 2243 | 4.7 | 756 | 6.0 | 110 | 2.6 | 218 | 18.1 | 516.6 (3)*** |

| Depression | 389 | 0.8 | 168 | 1.3 | 44 | 1.0 | 13 | 1.1 | 29.1 (3)*** |

| Anxiety | 1583 | 3.3 | 702 | 5.5 | 170 | 4.0 | 61 | 5.1 | 140.3 (3)*** |

| Other mental and behavioural disorders | 7432 | 15.6 | 2647 | 20.9 | 593 | 14.0 | 307 | 25.5 | 294.0 (3)*** |

| AMI | 5508 | 11.5 | 1861 | 14.7 | 536 | 12.6 | 187 | 15.5 | 104.5 (3)*** |

| Pulmonary disease | 8671 | 18.2 | 2955 | 23.3 | 664 | 15.6 | 251 | 20.9 | 208.6 (3)*** |

| Diabetes | 12 408 | 26.0 | 3800 | 30.0 | 1118 | 26.3 | 300 | 24.9 | 83.8 (3)*** |

| Diabetes with complications | 12 833 | 26.9 | 4089 | 32.3 | 1290 | 30.4 | 313 | 26.0 | 156.6 (3)*** |

| Renal disease | 11 066 | 23.2 | 4148 | 32.7 | 1433 | 33.7 | 450 | 37.4 | 708.5 (3)*** |

- AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ICU, intensive care unit; IRSD, the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage; LOS, length of stay; SEIFA, Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas.

- a Median (interquartile range).

- b A total of 937 urban/rural status not known and not included.

- c A total of 943 SEIFA IRSD status not known and not included.

- d Excluding congestive heart failure and mental and behavioural disorders.

- *** P < 0.0001.

Examining LOS for the first readmission revealed that individuals with CHF with an unplanned readmission had a significantly longer LOS (median: 5 days, IQR: 2–11, P < 0.0001) compared with individuals who had a planned readmission (median: 1 day, IQR: 1–4). An unplanned first readmission was also associated with higher total number of days in hospital (median: 8 days, IQR: 4–18, P < 0.0001) during the 28 day follow-up period than a planned first readmission (median: 6 days, IQR: 2–16). Further breakdown showed that unplanned CHF readmissions had a slightly longer LOS (median: 5 days, IQR: 3–11, P < 0.0001) than unplanned other-cause readmissions (median: 5 days, IQR: 2–11). The LOS of the index admission followed with an unplanned CHF readmission, however, was slightly shorter (median: 5 days, IQR: 3–10, P = 0.004) compared with index admission followed by other-cause unplanned readmission (median: 6 days, IQR: 3–11).

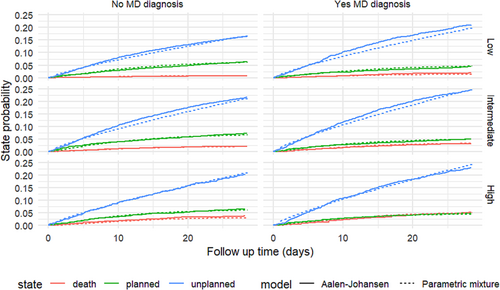

The competing risk model showed that the probability of an unplanned readmission was associated with a mental disorder diagnosis, the number of comorbidities, and frailty status. CHF adults with a mental disorder diagnosis who had ≥3 comorbidities and an intermediate frailty status had the highest probability of having an unplanned readmission within 28 days at 29.8% (95% CI: 24.68–35.73%) conditional on not having a planned readmission or death prior to the unplanned readmission. Adults with CHF without a mental disorder diagnosis had a 4% lower probability (25.7%, 95% CI: 21.73–30.27%) of having an unplanned readmission within 28 days. Amongst adults who had a lower probability of an unplanned readmission (i.e. a patient with nil comorbidities and low frailty scores), the estimated probability of an unplanned readmission increased from 13.6% (95% CI: 12.22–15.46%) to 16.3% (95% CI: 14.09–19.14%) when the individual had a mental disorder diagnosis (Table 2). Modelling on specific mental disorders showed that CHF adults with an anxiety disorder diagnosis who had ≥3 comorbidities and high frailty scores had more than one in three chances (34.9%, 95% CI: 28.66–42.20%) of experiencing an unplanned readmission (Table 3). Figure 2 shows the parametric mixture model estimation and the Aalen–Johansen estimators for competing risk for a CHF adult with one to two comorbidities by mental disorder and frailty status.

| Number of comorbiditiesb | Frailty score | Mental disorder | Probability (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | Low | No | 13.62 | (12.22, 15.46) |

| Nil | Low | Yes | 16.26 | (14.09, 19.14) |

| 1–2 | Low | No | 16.59 | (14.24, 19.17) |

| 1–2 | Low | Yes | 19.70 | (16.60, 23.73) |

| ≥3 | Low | No | 20.48 | (17.53, 23.88) |

| ≥3 | Low | Yes | 24.21 | (20.47, 28.90) |

| Nil | Intermediate | No | 17.56 | (15.04, 20.35) |

| Nil | Intermediate | Yes | 20.61 | (17.21, 24.81) |

| 1–2 | Intermediate | No | 21.16 | (17.32, 25.05) |

| 1–2 | Intermediate | Yes | 24.70 | (20.45, 29.83) |

| ≥3 | Intermediate | No | 25.71 | (21.73, 30.27) |

| ≥3 | Intermediate | Yes | 29.84 | (24.68, 35.73) |

| Nil | High | No | 17.39 | (14.98, 20.17) |

| Nil | High | Yes | 20.21 | (16.98, 24.22) |

| 1–2 | High | No | 20.98 | (17.58, 24.95) |

| 1–2 | High | Yes | 24.27 | (20.29, 29.42) |

| ≥3 | High | No | 25.55 | (21.55, 30.18) |

| ≥3 | High | Yes | 29.39 | (24.46, 35.40) |

- CI, confidence interval.

- The bold value highlights the highest probability of unplanned readmission and its associated characteristics.

- a Model also adjusted for Aboriginality.

- b Excluding congestive heart failure and mental health and behavioural disorders.

| Number of comorbiditiesb | Frailty score | Anxiety disorder | Probability (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | Low | No | 13.76 | (12.12, 15.40) |

| Nil | Low | Yes | 18.89 | (15.95, 22.11) |

| 1–2 | Low | No | 16.82 | (14.33, 19.61) |

| 1–2 | Low | Yes | 22.77 | (18.83, 27.17) |

| ≥3 | Low | No | 20.78 | (17.68, 24.11) |

| ≥3 | Low | Yes | 27.58 | (22.95, 32.98) |

| Nil | Intermediate | No | 18.07 | (15.61, 20.96) |

| Nil | Intermediate | Yes | 24.30 | (20.51, 28.63) |

| 1–2 | Intermediate | No | 21.84 | (18.83, 26.33) |

| 1–2 | Intermediate | Yes | 28.88 | (23.97, 34.59) |

| ≥3 | Intermediate | No | 26.55 | (22.17, 31.58) |

| ≥3 | Intermediate | Yes | 34.33 | (28.38, 41.20) |

| Nil | High | No | 18.38 | (15.69, 21.78) |

| Nil | High | Yes | 24.66 | (20.46, 29.71) |

| 1–2 | High | No | 22.23 | (18.55, 26.59) |

| 1–2 | High | Yes | 29.32 | (23.97, 35.60) |

| ≥3 | High | No | 27.05 | (22.86, 32.47) |

| ≥3 | High | Yes | 34.90 | (28.66, 42.20) |

- CI, confidence interval.

- The bold value highlights the highest probability of unplanned readmission and its associated characteristics.

- a Model also adjusted for Aboriginality.

- b Excluding congestive heart failure and mental health and behavioural disorders.

Multivariable cause-specific modelling showed that adults with CHF who also had a mental disorder diagnosis had a higher risk of an unplanned readmission within 28 days (hazard ratio: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.15–1.27) compared with adults without a mental disorder diagnosis after adjusting for patient-level factors. In addition, being aged ≥85 years (hazard ratio: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.11–1.28), having ≥3 comorbidities (hazard ratio: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.25–1.46), and having an intermediate (hazard ratio: 1.34, 95% CI: 1.28–1.40) or high (hazard ratio: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.27–1.47) frailty score were also associated with a greater risk of an unplanned readmission. Being female (hazard ratio: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.89–0.97) and living in regional or remote area (hazard ratio: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.75–0.92) were both associated with a lower risk of an unplanned readmission (Harrell's c-index: 0.60). Multivariable cause-specific modelling for separated mental health comorbidities found that CHF adults diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (hazard ratio: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.35–1.65) had the highest risk of an unplanned readmission compared with dementia (hazard ratio: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98–1.17), depression (hazard ratio: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.81–1.21), or other mental disorders (hazard ratio: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.06–1.19) (Harrell's c-index: 0.61) (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Model 1a | Model 2a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHR | 95% CI | P-value | AHR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age group | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–64 | 1 | — | 1 | — | ||

| 65–74 | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) | ||

| 75–84 | 1.10 | (1.03, 1.18) | 1.11 | (1.04, 1.19) | ||

| ≥85 | 1.19 | (1.11, 1.28) | 1.21 | (1.12, 1.30) | ||

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 1 | — | 1 | — | ||

| Female | 0.93 | (0.89, 0.97) | 0.92 | (0.89, 0.96) | ||

| Urban/rural | <0.001 | |||||

| Urban | 1 | — | 1 | — | ||

| Rural | 0.83 | (0.75, 0.92) | 0.83 | (0.75, 0.92) | ||

| Number of comorbiditiesb | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Nil | 1 | — | 1 | — | ||

| 1–2 | 1.14 | (1.08, 1.21) | 1.14 | (1.08, 1.21) | ||

| ≥3 | 1.35 | (1.25, 1.46) | 1.35 | (1.25, 1.46) | ||

| Frailty scoreb | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 1 | — | 1 | — | ||

| Intermediate | 1.34 | (1.28, 1.40) | 1.34 | (1.28, 1.41) | ||

| High | 1.37 | (1.27, 1.47) | 1.38 | (1.28, 1.48) | ||

| Mental and behavioural disorders | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 1 | — | ||||

| Yes | 1.21 | (1.15, 1.27) | ||||

| Dementia | 0.13 | |||||

| No | 1 | — | ||||

| Yes | 1.07 | (0.98, 1.17) | ||||

| Depression | >0.9 | |||||

| No | 1 | — | ||||

| Yes | 0.99 | (0.81, 1.21) | ||||

| Anxiety | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 1 | — | ||||

| Yes | 1.49 | (1.35, 1.65) | ||||

| Other mental and behavioural disorders | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 1 | — | ||||

| Yes | 1.13 | (1.06, 1.19) | ||||

- AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

- a Model also adjusted for COVID-19 period, discharge facility, Aboriginality, and diagnosis of substance and alcohol dependency, acute myocardial infarction, and pulmonary and renal diseases during lookback period.

- b Excluding congestive heart failure and mental health and behavioural disorders.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of mental disorders along with other factors on 28 day unplanned readmission for adults after a CHF admission. The study found that having a mental disorder, in particular an anxiety disorder, increased the risk of an unplanned readmission within 28 days following a CHF admission, after taking into account competing events like death before readmission and planned readmission, as well as personal-level factors. However, a diagnosis related to dementia or depression was not associated with significant differences in unplanned readmission.

This study found that having a mental disorder diagnosis increased the risk of an unplanned readmission within 28 days following a CHF admission by 21% and that there was a 49% higher risk of readmission if the individual had an anxiety diagnosis. While some studies have identified that depression and cognitive impairment were associated with a higher rate of hospital readmission and/or mortality for patients admitted with CHF,9, 12, 26-28 the evidence around the impact of anxiety disorder on readmission and mortality has been mixed.7, 8, 12 Recently, Lin et al. identified an association between anxiety and mortality at 18 months after discharge for patients with heart failure.29 There are also some established links between anxiety and poor health outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease, which often co-occurs with CHF.30, 31 While the current study found that having a depression diagnosis was not independently associated with an increased risk of readmission, this might be partially due to the prevalence of depression being very low (1.0%). Hospital administrative data have a tendency to under-enumerate chronic conditions including mental disorders like depression and anxiety, as guidelines focus on coding of comorbidities that relate to the admission and not all comorbidities or relevant medical history.32, 33 It also has been suggested that mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, are often underdiagnosed in CHF patients due to the commonality of symptoms.7, 8 The selection of a 28 day period for assessing unplanned readmissions in this study aligns with the health system performance framework set by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. This standard timeframe, while administratively convenient, also poses limitations in capturing longer term impacts of mental disorders on readmission, particularly in cases like adult with depression and CHF where the effect may evolve over a more extended period. Further research to explore the impact of varying readmission periods is needed to fully understand the nuances of different mental disorders in CHF patient outcomes.

Having a dementia diagnosis did not show a significant effect on unplanned readmissions in the current study. This may be because a relatively high proportion (19.2%) of patients with dementia at the index admission were admitted from and/or discharged to a residential aged care facility (RACF). Previous studies have identified that older adults with dementia living in RACFs have lower hospital readmissions than community-dwellers with other conditions.34 In addition, for adults with CHF and advanced dementia living in RACF, the goals of care might have shifted to comfort and palliation-orientated instead of aggressive treatments involving hospitalization.35 However, cognitive impairment tends to have a negative impact on an individual's ability to self-care, education about chronic disease management, adherence to treatment, and communication with health professionals. Providing supporting services that address social and environmental factors in addition to clinical management for older adults with CHF would likely improve quality of life for older community-dwellers. Differences in recognizing cognitive impairment may also contribute to variation in readmission risk. Previous studies involving CHF patients living with a cognitive impairment are mostly based on cognitive function testing scores instead of diagnosis classifications.26-28 The relatively low prevalence of all mental disorders in the hospital records could indicate that more clinical assessment on mental comorbidities during hospital admission is needed for adults living with CHF.

The current study found that older adults aged ≥85 years, those with a higher number of comorbidities, or those with an increased frailty risk have higher risk of unplanned readmission. This finding aligns with previous research.15-18 The association between multiple comorbidities, increased frailty, and greater readmission risk highlights the importance of integrated and multidisciplinary care for older adults with chronic conditions. It is worth noting that the inclusion of hospital frailty risk, a relatively new measure developed in 2018 to capture frailty using hospital administrative data in older people,21 has not been commonly included in studies focusing on readmissions in adults with CHF. The current results suggest that, despite some overlap with Charlson comorbidities, frailty risk can serve as an additional tool alongside the Charlson in predicting readmission risk for adults with CHF. The utilization of the hospital frailty risk tool may prove beneficial for researchers working with administrative health data.

If the first readmission was an unplanned readmission, then this was associated with a longer LOS, when compared with planned readmissions following a CHF admission. This is consistent with the study of Robertson et al. who found likewise.24 Further analysis of the first unplanned readmission showed that CHF readmissions tended to have a longer LOS per readmission and a longer total number of days in hospital during the follow-up period compared with readmissions for other causes. Interestingly, when comparing the LOS of the index admission, the current study found a slightly shorter LOS for those who had an unplanned CHF readmission. These findings suggest that comprehensive and integrated clinical care for adults with CHF during the index hospitalization is likely to be more efficient and optimal for both patient outcomes and hospital resources.

Contrary to one previous study that found that CHF patients living in outer regional, remote, or very remote areas in Australia had a higher relative risk of readmission,17 the current study showed that living in regional and remote areas in NSW was associated with a lower risk of an unplanned readmission. This is potentially linked to a higher rate of index admissions in regional and rural areas, due to lack of adequate primary care resources, as well as limitations and constraints to access services in these locations.36 Clark et al. have shown that there is inequity in the prevalence of CHF and the distribution of CHF management programme in rural Australia.37 This could potentially contribute to a higher rate of index hospitalization in regional and rural areas and is not reflective of short-term readmission for adults with CHF.

One of the key strengths of the study is that it is a population-level, patient-level analysis that allows a large range of sociodemographic and health characteristics to be investigated. Using a population-level retrospective cohort design also helped to minimize any selection bias. Study limitations include using hospital admission records for mental disorder ascertainment. Hospital administrative data are associated with low sensitivities in ascertainment of chronic disease and mental disorders due to the focus on capturing comorbidities directly related to an admission,32, 33 therefore excluding comorbidities only identified in primary care. The use of a 12 month lookback period to identify comorbidities goes some way to mitigate this problem of identification of comorbidities. There was no information available on clinical characteristics, such as results from conventional transthoracic echocardiogram, medication usage or laboratory tests (e.g. heart rate and blood results), and a lack of detailed social sociodemographic information, such as whether an individual lived alone. Such information has previously been proven to be good predictors for readmission and mortality for CHF adults.26, 27, 29 Despite the large sample size, power was limited for detailed breakdown of multiple covariates in the competing risk model. Combined with a relatively short follow-up time, the CIs produced by the competing risk model were relatively wide. Given that not all mental disorders are well captured in hospital administrative data,33 additional research is warranted to explore the impact of varying levels of mental disorder severity on CHF outcomes and to identify more effective interventions targeted for individuals. These efforts are essential for improving the quality of care provided to adults with CHF.

In conclusion, the current study suggests that interventions to reduce the prevalence of mental disorders, especially anxiety disorder, in adults with a CHF admission may contribute to reducing the rate of unplanned readmissions. While the efficacy of mental health interventions in reducing readmissions has shown mixed results,38 exploring both pharmacological treatments and non-pharmacological therapies like cognitive-behavioural therapy and exercise training could offer benefits.7, 8, 38, 39 Further research into the mechanisms through which mental disorders influence unplanned readmissions in CHF patients would be vital for crafting effective interventions at both the individual and healthcare system levels. It has been suggested that post-discharge interventions, such as home care for CHF patients living in the community, outpatient heart failure clinics, and public health interventions like improving mental health treatment infrastructure, could also effectively reduce the rate of readmission for CHF patients.38 The potential for non-pharmacological treatments to reduce readmissions has highlighted the need for integrated care to foster collaboration amongst hospitals and primary care providers that included a referral system from acute care to community services to assure continuity of care. Systematic screening for early detection and intervention has been recommended in the literature,7, 38, 39 and tools have been developed and recommended by the American Heart Association.40 These findings underscore the importance of systematic screening during hospital admission for common mental disorders in CHF patients and the necessity of integrating multidisciplinary care in discharge plan to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Muhammad Hafiz Khusyairi, Ian Powell, and Malcom Gillies for their valuable statistical feedback. We thank the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) for data linkage and the NSW Ministry of Health for providing access to population health data. This work was completed while Zhisheng Sa was employed as a trainee on the NSW Biostatistics Training Program funded by the NSW Ministry of Health. She undertook this work while based at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University.

Open access publishing facilitated by Macquarie University, as part of the Wiley - Macquarie University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This project is funded by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Keeping Australians Out of Hospital (APP1178554).

Appendix

- alcohol dependency/abuse history: F10, Y90, Y91, Z50.2, Z71.4, and Z72.1;

- substance dependency/abuse history: F11–F16, F19, Z50.3, Z71.5, and Z72.2;

- all mental disorders: F00–F99, G30, and G31;

- anxiety disorder: F40–F48;

- dementia: F00–F03, F05.1, G30, and G31;

- depressive disorder: F20.4, F31.3, F31.4, F31.5, F32, F33, F34.1, F41.2, and F43.2;

- other mental disorders: all mental disorders code excluding anxiety, depressive disorders, and dementia code;

- obesity: E66 and U78.1; and

- smoking: F17, Z72.0, Z71.6, and Z86.43.