Characteristics of patients admitted with heart failure: Insights from the first Malaysian Heart Failure Registry

Abstract

Aims

Heart failure (HF) is a growing health problem, yet there are limited data on patients with HF in Malaysia. The Malaysian Heart Failure (MY-HF) Registry aims to gain insights into the epidemiology, aetiology, management, and outcome of Malaysian patients with HF and identify areas for improvement within the national HF services.

Methods and results

The MY-HF Registry is a 3-year prospective, observational study comprising 2717 Malaysian patients admitted for acute HF. We report the description of baseline data at admission and outcomes of index hospitalization of these patients. The mean age was 60.2 ± 13.6 years, 66.8% were male, and 34.3% had de novo HF. Collectively, 55.7% of patients presented with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III or IV; ischaemic heart disease was the most frequent aetiology (63.2%). Most admissions (87.3%) occurred via the emergency department, with 13.7% of patients requiring intensive care, and of these, 21.8% needed intubation. The proportion of patients receiving guideline-directed medical therapy increased at discharge (84.2% vs. 93.6%). The median length of stay (LOS) was 5 days, and in-hospital mortality was 2.9%. Predictors of LOS and/or in-hospital mortality were age, NYHA class, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and comorbid anaemia. LOS and in-hospital mortality were similar regardless of ejection fraction.

Conclusions

The MY-HF Registry showed that the HF population in Malaysia is younger, predominantly male, and ischaemic-driven and has good prospects with hospitalization for optimization of treatment. These findings suggest a need to reassess current clinical practice and guide resource allocation to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a growing health problem, affecting over 26 million people worldwide.1, 2 The health and economic burden of HF is primarily driven by the high hospitalization and mortality rates in Asian countries.3 Global epidemiological trends showed that Asian patients present at a younger age but exhibit more severe clinical symptoms and with higher rates of mechanical ventilation than Western patients with HF.4, 5 There is also a greater risk of death from HF in the Asia Pacific compared with the global average.6

Asian registries such as Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Registry—Asia Pacific (ADHERE-AP) and Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN-HF) Registry highlighted striking variations in HF characteristics between countries within Asia, likely caused by risk factor profile, comorbidity burden, life expectancy, and standard of living.7-9 Despite local guidelines, patients with HF are also undertreated in Asian countries, with fewer patients discharged on guideline-recommended therapies compared with patients in Western countries.10, 11 Given the public health importance of HF, there is an urgency to fill these knowledge gaps and to understand the barriers to preventive drug and device therapy in Asian patients.8

Apart from a small number of retrospective single-centre studies, there are limited data about patients with HF in Malaysia.12, 13 Moreover, Malaysian patients represent only a small portion of data in Asian registries.8, 9 Therefore, the generalization of HF characteristics and outcomes in Malaysian patients using these data may be inaccurate. The Malaysian Heart Failure (MY-HF) Registry was initiated by the National Heart Association of Malaysia (NHAM) to gain insights into the epidemiology, aetiology, management, and outcome of Malaysian patients with HF and identify areas for improvement within the national HF services. Herein, we report the MY-HF Registry's baseline characteristics, treatment pattern, and outcomes of index hospitalization of patients with HF.

Methods

Study design

MY-HF Registry is a 3 year prospective, observational study of patients admitted for acute HF [New York Heart Association (NYHA) Classes II–IV] at 18 study sites in West and East Malaysia. Study sites were tertiary medical centres with a broad spectrum of medical, cardiology, and HF speciality units regularly admitting patients with acute HF and following them as outpatients. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality and hospital readmission for acute decompensated HF (ADHF) at 1 year. The secondary endpoint was in-hospital all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality during index hospitalization and readmission, as well as all-cause mortality at 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year. This report highlights the baseline findings, length of stay (LOS), and in-hospital all-cause mortality of the MY-HF Registry from admission to discharge.

MY-HF Registry enrolled patients between August 2019 and December 2020. As of 31 December 2021, the registry had completed its 1 year follow-up. Malaysian patients who meet all of the following criteria were eligible for the study: (i) aged ≥18 years with a documented diagnosis of HF by the in-patient attending physician at enrolment, (ii) visited the hospital owing to ADHF (readmission for worsening HF or de novo HF) during the enrolment period, (iii) had left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) assessment performed within 6 months of admission, and (iv) required a minimum hospitalization of 24 h for stabilization before discharge. Patients with severe pulmonary disease or pulmonary arterial hypertension, with life-threatening comorbidity with a life expectancy of <1 year, or unable to give consent were excluded. Eligible patients underwent a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and standard blood investigation if deemed necessary by the attending physician. Transthoracic echocardiogram (ECHO) was performed during admission or at subsequent follow-up (30 days after admission if the patient did not have department ECHO performed in the last 6 months).

MY-HF Registry protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committees of participating hospitals and was conducted according to the ethical standards described in the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed consent before data collection. Ethical approval for this study was also obtained from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-19-1530-47610).

Baseline variables and measures

The baseline variables were demographic information, NYHA functional status, date of HF diagnosis (if known), prior HF hospitalization and diagnostic/laboratory investigations, aetiology and comorbidities, lifestyle factors (smoking and alcohol consumption), and treatment before and after discharge (medication and device therapy). Outcome measures during index hospitalization were defined as the number of patients requiring intensive/critical care and ventilatory support, in-hospital mortality, and LOS. HF service performance measures were defined as the percentage of patients receiving guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), beta-blocker (BB), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA).

Data collection

Data for each patient were documented in an electronic case report form based on source documents (original data and patient records). Data were monitored centrally to ensure captured data were as per protocol. Data from participating sites were reported annually.

Statistical analysis and sample size

Descriptive statistics summarized demographic and clinical characteristics, laboratory evaluations, and in-hospital outcome. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation or median with a minimum and maximum range, while discrete variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Predictors of LOS were analysed using univariate and multivariate linear regression, while the univariate and multivariate logistic regression was applied to predictors of in-hospital mortality. All P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A sample size of 3600 was calculated based on reported outcomes from previous studies (ASIAN-HF Registry and ADHERE-AP).4, 14 Assuming a loss to follow-up of 20%, the final estimated sample size was ~3000 patients recruited over 1 year. However, the registry recruited fewer patients than the projected sample size due to the temporary closure of health facilities and services during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. LOS and in-hospital mortality analyses included data of patients who have died and excluded data of patients without LVEF.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 2717 patients were enrolled upon admission to one of the 18 participating hospitals across Malaysia (Supporting Information, Table S1). The cohort had a mean age of 60.2 ± 13.6 years and was predominantly male (66.8%). The mean body mass index (BMI) of the cohort was 27.3 ± 6.7 kg/m2 (Table 1). Active and former smokers accounted for 46.9% of the cohort. Alcohol dependence was reported in 7.0% of patients (Supporting Information, Table S2).

|

Baseline n (%) unless otherwise specified |

Total (N = 2717) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 60.17 (13.62) |

| <60 | 1204 (44.3) |

| ≥60 | 1513 (55.7) |

| Male | 1814 (66.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.3 (6.7) |

| Medical history | |

| Previous CHF hospitalization | |

| Yes | 1221 (45.0) |

| No | 1496 (55.0) |

| Status at admission | |

| Reasons for hospitalization | |

| DHF with history of HF | 1610 (59.2) |

| De novo HF | 931 (34.3) |

| Others | 176 (6.5) |

| NYHA class | |

| II | 1203 (44.3) |

| III | 1230 (45.3) |

| IV | 284 (10.4) |

| LVEF (%), median (min, max) | 34.0 (8.8, 80.0) |

| HFrEF (LVEF ≤ 40%) | 1755 (64.6) |

| HFmrEF (LVEF = 41–49%) | 309 (11.4) |

| HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%) | 587 (21.6) |

| Missing | 66 (2.4) |

| Investigations at admission | |

| Electrocardiography | |

| Sinus rhythm | 2016 (74.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 437 (16.1) |

| Pacemaker rhythm | 34 (1.2) |

| Others | 230 (8.5) |

| Biomarker data | 449 (16.5) |

| NT-proBNP | 366 (81.5) |

| BNP | 83 (18.5) |

| Troponin T/I | 1441 (53.0) |

| Positive | 1056 (73.3) |

| Negative | 352 (24.4) |

| Missing | 33 (2.3) |

| Biometrics at admission, mean (SD)a | |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 (2.0) |

| Blood Hb (g/dL) | 12.7 (2.3) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 57.9 (28.2) |

| >60 | 1203 (44.3) |

| 30–60 | 1036 (38.1) |

| <30 | 440 (16.2) |

| Missing | 38 (1.4) |

- ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CHF, chronic heart failure; DHF, decompensated heart failure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hb, haemoglobin; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

- N denotes total number of patients, and n denotes number of patients. Detailed data are available in Supporting Information, Table S2.

- a Corresponding number of patients, n: HbA1c = 394 and blood Hb = 2569.

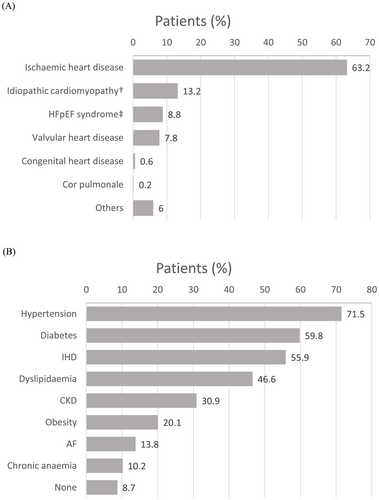

One-third of the cohort (34.3%) had de novo HF, and ischaemic heart disease (IHD) is an underlying aetiology for most HF cases (63.2%; Figure 1). Collectively, more than half of the patients presented with NYHA Classes III (45.3%) and IV (10.4%) at admission, and 87.3% were admitted via the emergency department (Supporting Information, Table S2). Hypertension, diabetes, IHD, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and obesity accounted for 71.5%, 59.8%, 55.9%, 46.6%, 30.9%, and 20.1% of the comorbidities, respectively (Figure 1). Device therapy utilization was low (9.8%). The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures (SBP and DBP) were 138.4 ± 28.3 and 81.9 ± 17.5 mmHg, respectively, while estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 57.9 ± 28.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Table 1) and serum creatinine was 145.9 ± 119.6 μmol/L (Supporting Information, Table S2). The mean blood haemoglobin and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of the cohort were 12.7 ± 2.30 g/dL and 7.6 ± 2.0%, respectively.

ECG documented that atrial fibrillation was present in 16.1% of patients and only 3% had complete left bundle branch block (LBBB). Complete ECHO data were available for 2651 patients (median LVEF = 34%), which were categorized into three subgroups as defined in the National Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of HF,15 namely, HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; LVEF ≤ 40%), HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF; LVEF ≥ 50%), and HF with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF; LVEF = 41–49%). The prevalence of HFrEF (64.6%) was higher than that of HFpEF (21.6%) and HFmrEF (11.4%) within the cohort (Table 1). Natriuretic peptide tests were only performed in 16.5% of patients, with N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) being more commonly used (81.5%).

Treatment pattern

The proportion of patients with prior history of HF receiving at least one GDMT for HF increased from 84.2% before admission to 93.6% at discharge. Although BBs were the most frequently prescribed medication before admission and at discharge, there was a marked increase in the proportion of patients receiving ARNI (+78.9%), BB (+17.0%), MRA (+30.5%), and ivabradine (+42.2%) at discharge (Table 2). The combination of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (ACEI or ARB) + BB was the most prescribed HF regimen at discharge, followed by ACEI + BB + MRA and ARNI + BB. Of the total cohort, 4% of patients required mechanical circulatory support and mechanical fluid removal (Supporting Information, Table S2).

| GDMT n (%) unless otherwise specified |

Pre-admissiona N = 1610 |

On dischargeb N = 2638 |

|---|---|---|

| No HF medication | 255 (15.8) | 169 (6.4) |

| Receiving at least one HF medication | 1355 (84.2) | 2469 (93.6) |

| HF medication, n (%) | ||

| ACEI | 581 (36.1) | 992 (37.6) |

| ARB | 141 (8.8) | 221 (8.4) |

| ARNI | 141 (8.8) | 414 (15.7) |

| Beta-blocker | 1116 (69.3) | 2140 (81.1) |

| MRA | 538 (33.4) | 1149 (43.6) |

| Ivabradine | 133 (8.3) | 312 (11.8) |

| Number of HF medicationsc | ||

| 1 | 478 (29.7) | 682 (25.8) |

| 2 | 518 (32.2) | 936 (35.5) |

| 3 | 301 (18.7) | 733 (27.8) |

| 4 and more | 58 (3.6) | 118 (4.5) |

| Combination of HF medicationsd | ||

| ACEI, beta-blocker, and MRA | 195 (12.1) | 399 (15.1) |

| ARB, beta-blocker, and MRA | 49 (3.0) | 105 (4.0) |

| ARNI, beta-blocker, and MRA | 68 (4.2) | 250 (9.5) |

| ACEI or ARB and beta-blocker | 568 (35.3) | 1048 (39.7) |

| ARNI and beta-blocker | 101 (6.3) | 336 (12.7) |

| Other medication | ||

| Diuretics | 1155 (71.7) | 2239 (84.9) |

| Digitalis | 92 (5.7) | 130 (4.9) |

| Statins | 1113 (69.1) | 2020 (76.6) |

| Nitrates | 241 (15.0) | 436 (16.5) |

| Anticoagulants | 261 (16.2) | 529 (20.1) |

| Antiplatelets | 1065 (66.2) | 1863 (70.6) |

| Device therapye | — | 30 (1.1) |

| Cardiac rehabilitation referral | — | 278 (10.5) |

- ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

- N denotes total number of patients, and n denotes number of patients.

- a Includes decompensated HF with medical history of HF (denominator = 1610).

- b Excludes 79 death during admission or at discharge (denominator = 2638).

- c Any one or a combination of ACEI, ARB, ARNI, beta-blocker, MRA, and/or ivabradine.

- d Combination of all agents listed.

- e Device therapy includes pacemaker, CRT-P, CRT-D, and ICD.

Predictors and outcome

The median LOS in the hospital was 5 days; in-hospital mortality was 2.9% (Table 3). Most deaths were due to cardiovascular causes (worsening HF, 47.3%; cardiac arrest, 18.2%; and myocardial infarction, 5.5%). Non-cardiac-related deaths (26.6%) were commonly caused by infection and sepsis (66.7%). Multivariate analysis revealed that patients aged >60 had significantly shorter LOS (Table 4) than younger patients. NYHA Class III or IV and eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were identified as a predictor of prolonged LOS and in-hospital mortality. Anaemia was associated with significantly longer LOS but not in-hospital mortality. Notably, LOS and in-hospital mortality were similar regardless of the LVEF subgroup (Tables 4 and 5).

| Baseline n (%) unless otherwise specified |

Total (N = 2717) |

|---|---|

| Outcome at discharge | |

| Length of stay (days), median (min, max) | 5 (1, 161) |

| Discharge status | |

| Alive | 2607 (96.0) |

| Transferred to other centres | 31 (1.1) |

| Dead | 79 (2.9) |

| Cardiac causes of deatha | 55 (69.6) |

| Myocardial infarctionb | 3 (5.5) |

| Worsening HFb | 26 (47.3) |

| Sudden cardiac arrestb | 10 (18.2) |

| Othersb | 14 (25.4) |

| Missingb | 2 (3.6) |

| Non-cardiac causes of deatha | 21 (26.6) |

| Infection or sepsisc | 14 (66.7) |

| Othersc | 7 (33.3) |

| Missing | 3 (3.8) |

- N denotes total number of patients, and n denotes number of patients. Detailed data are available in Supporting Information, Table S2.

- a Percentage calculated based on the total number of patients discharged dead (n = 79).

- b Percentage calculated based on death by cardiac causes (n = 55).

- c Percentage calculated based on death by non-cardiac causes (n = 21).

| Risk factors | Unadjusted coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted coefficient (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–<40a | — | — | — | — |

| 40–60 | −0.90 (−2.19, 0.38) | 0.168 | −1.31 (−2.62, 0.01) | 0.052 |

| >60 | −1.18 (−2.44, 0.07) | 0.065 | −2.03 (−3.37, −0.69) | 0.003 |

| Gender | ||||

| Malea | — | — | — | — |

| Female | −0.25 (−0.97, 0.48) | 0.502 | NS | NS |

| Reason for hospitalization | ||||

| DHF with medical history of HFa | — | — | — | — |

| De novo HF | −0.26 (−0.99, 0.48) | 0.490 | NS | NS |

| Others | 0.95 (−0.46, 2.35) | 0.186 | NS | NS |

| NYHA class at admission | ||||

| NYHA I–IIa | — | — | — | — |

| NYHA III–IV | 1.82 (1.14, 2.51) | <0.0001 | 1.77 (1.06, 2.48) | <0.0001 |

| LVEF | ||||

| HFrEF (LVEF ≤ 40%)a | — | — | — | — |

| HFmrEF (LVEF = 41–49%) | −0.25 (−1.34, 0.83) | 0.647 | NS | NS |

| HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%) | −0.04 (−0.88, 0.80) | 0.925 | NS | NS |

| eGFR at admission (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| ≥60a | — | — | — | — |

| <60 | 1.63 (0.93, 2.32) | <0.0001 | 1.73 (0.99, 2.46) | <0.001 |

- ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; CI, confidence interval; DHF, decompensated heart failure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LOS, length of stay; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NS, not significant; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

- a Reference. Risk predictors of LOS including mode of admission, comorbidities, HF duration, history of HF hospitalization and HF medication prior to admission are available in Supporting Information, Table S3.

| Risk factors |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–<40a | 1.00 (—) | — | — | — |

| 40–60 | 0.89 (0.38, 2.06) | 0.785 | NS | NS |

| >60 | 0.97 (0.43, 2.19) | 0.938 | NS | NS |

| Gender | ||||

| Malea | 1.00 (—) | — | NS | NS |

| Female | 1.10 (0.68, 1.77) | 0.693 | NS | NS |

| Reason for hospitalization | ||||

| DHF with history of HFa | 1.00 (—) | — | NS | NS |

| De novo HF | 1.37 (0.84, 2.26) | 0.209 | NS | NS |

| Others | 2.83 (1.41, 5.67) | 0.003 | NS | NS |

| NYHA class at admission | ||||

| NYHA I–IIa | 1.00 (—) | — | 1.00 (—) | — |

| NYHA III–IV | 2.26 (1.35, 3.78) | 0.002 | 2.07 (1.23, 3.49) | 0.006 |

| LVEF | ||||

| HFrEF (LVEF ≤ 40%)a | 1.00 (—) | — | NS | NS |

| HFmrEF (LVEF = 41–49%) | 1.04 (0.51, 2.15) | 0.906 | NS | NS |

| HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%) | 1.10 (0.64, 1.91) | 0.730 | NS | NS |

| eGFR at admission (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| ≥60a | 1.00 (—) | — | 1.00 (—) | — |

| <60 | 2.73 (1.60, 4.67) | <0.0001 | 2.49 (1.46, 4.27) | 0.001 |

- ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; CI, confidence interval; DHF, decompensated heart failure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NS, not significant; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OR, odds ratio.

- a Reference. Risk predictors of mortality including mode of admission, comorbidities, HF duration, history of HF hospitalization and HF medication prior to admission are available in Supporting Information, Table S4.

Discussion

Clinical profile of patients with HF in Malaysia

MY-HF Registry is the first Malaysian multicentre, observational, and prospective study of 2717 patients from 18 participating sites, comprising hospitals operating under the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Higher Education, the National Heart Institute, and a private cardiac hospital within the country. Patients in the MY-HF Registry were younger than those in Western regions (mean age of 60 vs. ≥70 years).4, 5, 16 Almost half of these patients had been hospitalized for HF, and a substantial proportion presented with more severe clinical features (NYHA Stages III and IV), requiring emergency care and invasive ventilatory support on admission. The ADHF patient profile observed in the MY-HF Registry was consistent with the unique ‘Asian HF phenotype’ (i.e. younger and sicker) as described in other registries7, 8, 17 and often linked to prevalent cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, lung disease, renal disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease. These factors can be attributed to low socioeconomic and educational background, suboptimal health awareness, and poor lifestyle choices.7

Despite the younger age, Malaysian HF patients had a higher prevalence of diabetes (59.8%) and a similar prevalence of hypertension and IHD compared with the European cohort.5 Among Asian nations, the ASIAN-HF Registry showed that Southeast Asians, including Malaysians, had the highest burden of hypertension, diabetes, and IHD compared with Northeast and South Asians.8 The MY-HF Registry also reported a substantial proportion of patients with CKD. CKD in patients with HF is associated with an increased risk of mortality.18 Furthermore, managing concomitant HF and CKD can be challenging because most lifesaving GDMTs for HF can affect renal function and require careful assessment, monitoring, and understanding of the potential risks and benefits of treatment.19 Therefore, a multidisciplinary disease management strategy aimed at addressing risk factors and comorbidities is essential to treat underlying risk factors, aetiologies, and coexisting comorbidities in patients with HF.20

The role of natriuretic peptide testing in HF

Most patients enrolled in the MY-HF Registry received diagnostic investigations, including ECG, ECHO, chest X-ray, and serum creatinine evaluations. However, the use of natriuretic peptide tests was low in the MY-HF Registry. This could reflect the limited access to biomarker testing in some Malaysian hospitals. Guidelines recognize natriuretic peptides as important diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in HF.15, 20, 21 Thus, improving access to HF biomarker (NT-proBNP and BNP) testing, along with other clinical assessments, may guide clinicians in deciding treatment strategies.22

Guideline-directed medical therapy utilization in HF

Findings from the MY-HF Registry showed that hospitalization provides the opportunity to initiate GDMT in patients with HF and highlights the underutilization of HF medications in Malaysia. According to data captured in MY-HF Registry, the prescription rate of ACEI and ARB at discharge was lower than that in the Asia Pacific and Western regions.4, 5, 7 MY-HF Registry patients were most commonly prescribed with BBs, while patients in ADHERE-AP (particularly those with LVEF < 40%) were more likely to receive ACEI or ARB at discharge.7 Although the use of combination GDMT increased at discharge compared with before admission, the use of triple therapy (ACEI/ARB/ARNI + BB + MRA) was relatively low at admission (19.3%, patients with history of HF) and at discharge (28.6%, all discharged patients); ~50% of patients were on dual therapy (ACEI/ARB/ARNI + BB) at discharge. This highlights the need to optimize the use of combination drug therapy as stipulated by the various HF guidelines to improve survival and reduce the risk of HF hospitalization in patients with HF.15, 20, 21 Similarly, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker/defibrillator (CRT-P/D) are Class I recommendations to reduce morbidity and mortality risk in appropriately selected patients.20 Nevertheless, the uptake of ICD and CRT-P/D in Malaysia is low, possibly attributed to the high medical costs that limit access to device therapy, even in the face of proven benefits.

In-hospital outcomes of HF

In general, the burden of LOS (median of 5 days) in the MY-HF Registry was similar to that reported in international and regional registry studies [ADHERE, ADHERE-AP, and Get With The Guidelines—Heart Failure Registry (GWTG)] despite the differences in patient characteristics.4, 7, 16 In-hospital mortality among patients in this study (2.9%) was comparable with that of ADHERE-AP and Western registries (3–4%) despite more patients requiring mechanical ventilation.4, 7, 23

In our study, 55.3% of HF patients had low serum albumin levels upon admission, a higher prevalence compared with other studies (28–37%),24 likely due to a greater presence of diabetes mellitus and severe congestion at admission. A significant association was found between hypoalbuminaemia and increased in-hospital mortality (P < 0.0001), as well as longer hospital stays (P = 0.005), in univariate analysis, although this association was not evident in multivariate analysis.

A recent study of patient records from Ministry of Health hospitals reported an in-hospital mortality rate of 5.3% in patients with HF.25 Other retrospective and single-centre Malaysian studies reported a broader range of in-hospital mortality [IJN-ADHF (National Heart Institute of Malaysia): 7.2%, Sarawak General Hospital (SGH-HF): 7.5%, and Hospital Sungai Buloh: 1.7%].12, 13, 26 The disparity between these studies may be attributed to the different study designs, with retrospective data (i.e. IJN-ADHF) and its inherent limitations and single-centre studies, which are not generalizable to the Malaysian population. In comparison, MY-HF Registry—a multicentre prospective study—presents a fair representation of HF patients (and the use of GDMT) across Malaysia.

Previous studies indicate advanced age, severe NYHA class, and CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) as risk factors consistently associated with worse outcomes.12, 13, 25, 26 Other predictors include LVEF, lower SBP, diabetes mellitus, male gender, lower BMI, lower haemoglobin, and aortic stenosis.27 In line with these findings, MY-HF Registry showed that patients with NYHA Classes III and IV, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and comorbid anaemia and hospitalized due to precipitating factors such as acute coronary syndrome, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and anaemia are likely to have increased LOS. GWTG reported that patients with longer LOS have more comorbidities and higher disease severity at admission.28 Comorbidities such as renal dysfunction are likely to delay a patient's response to treatment, prevent the use of certain therapies, or require more time to manage.28 Contrarily, this study revealed a shorter LOS and reduced (although not statistically significant) likelihood of death with the elderly (>60 years). Young patients with a new diagnosis of HF may require in-depth evaluation for the potential causes of HF and time to respond to treatment, leading to a longer LOS. Notably, a study reported that patients with HFpEF, who are likely to be older, have lower in-hospital mortality and shorter LOS compared with HFrEF, which typically affects younger patients.29

Study implication

To date, MY-HF Registry is the largest multicentre, prospective cohort of ADHF admission in Malaysia, thus allowing for a more robust data set to be collected and analysed compared with previously reported studies by Ling et al. (n = 117), Raja Shariff et al. (n = 1307), Mohd Ghazi et al. (n = 4739), and Lee et al. (n = 105 399).12, 13, 24, 25 As more than 80% of patients participating in this registry had standard (department) ECHO performed by trained echocardiographers, the registry provides an opportunity to define the different spectrums of HF and evaluate current practice and outcomes in the era of established HF-guided medical treatment.

Study limitations

Potential biases include site selection and participation bias. MY-HF Registry recruited patients admitted for HF from large, urban tertiary hospitals (i.e. 17 government-affiliated centres and one private cardiac centre) based on HF population volume and the availability of cardiology expertise. While this ensured quality data, it is possible that rural sites are underrepresented; hence, data in the MY-HF Registry may not reflect the entire spectrum of patients with HF in Malaysia. Other biases were minimized by adjusting the known covariates using stratification and propensity score matching. Treatment effect variations between hospitals were standardized using fixed- and random-effects models. Missing demographic data and potential outliers were resolved using hot-deck imputation unless sourced from other forms of documentation. No imputation was performed for missing treatment and outcome data.

The absence of data concerning the dosages of GDMT administered before admission and at discharge, along with the registry's inability to capture information on adverse events, has resulted in a lack of recorded data for specific cases. In addition, we excluded patients with short life expectancy or severe comorbidities from our study, which may underestimate the real short-term prognosis of patients with acute HF. Furthermore, it is important to note that our study was conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, during which patients with HF may have chosen not to seek hospital care, potentially leading to an underrepresentation of individuals who unfortunately succumbed to HF in our registry.

Conclusions

MY-HF Registry showed that the profile of a Malaysian patient admitted for ADHF is consistent with previous reports of the Asian HF patient—young with severe clinical features and greater comorbidity burden than Western patients. Preliminary findings suggest a need to reassess current clinical practice patterns when managing patients with HF. Improving access to biomarker testing and optimizing the prescription of HF medications by enhancing the utilization of GDMT could lead to better patient outcomes. Nevertheless, these findings showed that hospitalization is a good opportunity to optimize treatment in patients with HF. The knowledge gained from the MY-HF Registry throughout the 3 year study period will be crucial in guiding resource allocation and planning preventive strategies to establish a patient-oriented HF clinical care system in Malaysia. This includes potential changes in budget allocation across different hospitals and healthcare setups, including budget allocation for medication, as well as adjustments in manpower planning and training to better address the specific healthcare needs highlighted in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for the permission to publish this paper. The authors also thank NHAM and the Novartis medical team especially Dr Mayuresh Fegade for their support and acknowledge the contribution of all study investigators, co-investigators, site coordinators, patients, and healthcare professionals involved in the study.

Conflict of interest

H.A.Z.A. serves as a speaker for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis; has received grants from the National Heart Centre Singapore, NHAM, Merck, and Sharp and Dohme; and reports consulting relationship with Boehringer Ingelheim. T.K.O. serves as a speaker for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis and reports consulting relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk. W.S.H. is an employee of Novartis Corporation (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd. None of the authors have any direct conflicts of interest related to this article.

Funding

MY-HF Registry was conducted by the National Heart Association of Malaysia (NHAM) with funding support from Novartis Corporation (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd. Data collection, management, and analysis were provided by Jau Shya of ClinData Consult Sdn Bhd and Lena Yeap of Stats Consulting Sdn Bhd under the engagement of NHAM. Medical writing assistance was provided by Jo-Ann Chuah, Poh Sien Ooi, and Veronica Yap of MIMS (Malaysia), which was sponsored by Novartis Corporation (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd and complied with the Good Publication Practice 3 guidelines.30