Clinical profile and midterm prognosis of left ventricular thrombus in heart failure

Abstract

Aims

We documented the midterm prognosis of left ventricular thrombus (LVT) in heart failure (HF) patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and ischaemic cardiomyopathy (ICM). We aimed to characterize patients with LVT in the context of HF with reduced (≤40%) left ventricular ejection fraction and evaluate their risk for death and/or embolic events, overall, and specifically in patients with ischaemic or non-ischaemic aetiology. We also intended to identify risk factors for LVT in patients with DCM.

Methods and results

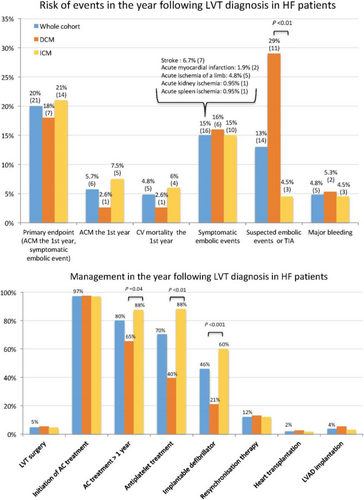

We included all HF patients (N = 105, age 56 ± 13) admitted from 2005 to 2018 in our institution for LVT without significant valve disease/prosthesis, heart transplant/left ventricular assist device, congenital heart disease, or acute myocardial infarction. Our primary endpoint was the 1 year risk of the composite of all-cause mortality (ACM) and symptomatic embolic events. Mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 23 ± 9%, and median BNP was 1795 pg/mL. Most (97%) patients were treated with vitamin K anticoagulants, and 64% had ICM. Symptomatic embolic events and/or ACM occurred in 20% of the population [embolic events (all within 30 days of LVT diagnosis) 15% and ACM 6%] and was similarly frequent in DCM or ICM (P > 0.05). Suspected/transient embolic events were more frequent in DCM (overall 13%; 29% in DCM vs. 5% in ICM, P < 0.01). Major bleeding occurred in 5% of patients. Left ventricular reverse remodelling occurred in 65% of patients, more frequently in DCM (86% in DCM vs. 65% in ICM, P = 0.02). In a case–control analysis matching DCM patients, BNP level was the only factor significantly associated with LVT (2447 pg/mL in LVT vs. 347 pg/mL, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Patients with LVT have markedly high natriuretic peptides and experience a 20% 1 year risk for embolic events and/or death following diagnosis despite anticoagulant treatment. Most patients have favourable remodelling/recovery. As all symptomatic embolic events occurred within 30 days of LVT diagnosis, a very careful initial management is warranted.

Introduction

Left ventricular thrombus (LVT) is a dreaded complication of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction or myocardial infarction. While its incidence after myocardial infarction has declined in the era of primary percutaneous intervention and with improvements of peri-procedural care, its reported occurrence ranges from 4% to 15% after an ST-elevation myocardial infarction.1 Importantly, the occurrence of systemic embolic events has been reported to be as high as 29%.2 In matched analysis, the presence of LVT identified with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was associated with a four-fold higher long-term incidence of embolism.3

Heart failure (HF) with reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF), due to an ischaemic (ICM) or non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), is an emerging source of LVT.4 In the setting of HF, several elements of Virchow's triad can be present; blood stasis is favoured by akinetic myocardial wall or severely decreased ventricular contraction, endothelium damage is favoured by necrosis or inflamed myocardium and increased shear stress, and hypercoagulable state can be increased by systemic inflammation, thrombophilia, and prothrombotic factor activation. As previous large studies did not specifically focused on HF patients,3 the incidence of LVT in HF, patients' characteristics, and prognosis are mostly unknown. Given this limited evidence, there are no clear recommendations regarding the diagnosis modalities and treatment of LVT in HF.

We aimed to characterize patients with LVT in the context of HF with reduced (≤40%) LVEF and evaluate their risk for death and/or embolic events, overall, and specifically in patients with ischaemic or non-ischaemic aetiology. We also intended to identify risk factors for LVT in patients with DCM.

Methods

Cohort study population

We extracted electronic medical records labelled with the diagnosis ‘intra-cardiac thrombosis’ or ‘intra-ventricular thrombosis’ admitted in our institution from January 2005 to July 2018. This database query extracted a list of 1223 hospital stays matching 658 patients. We included patients diagnosed in our institution with LVT using transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), MRI, or computed tomography (CT) scan. Patients with thrombosis limited to the atria and right cavities were excluded. In addition, we used the following exclusion criteria: ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction <1 month, concomitant severe valvular stenosis or mechanic valves, heart transplant or LV assist device, complex congenital heart diseases, and takotsubo.

The date of inclusion in this retrospective cohort was the date of LVT diagnosis. Clinical data at diagnosis, including TTE and MRI data, were reviewed and collected in a computerized database. We retrieved information regarding all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and symptomatic, transient, or suspected embolic events from routine clinical follow-up within 1 year of LVT diagnosis.

Cohort study outcomes

The composite primary endpoint was the occurrence of all-cause mortality and/or symptomatic embolic event within 1 year of LVT diagnosis reported in their medical file. Symptomatic embolic events were defined as persistent clinical symptoms suggestive of embolism (neurological deficit, ischaemic symptoms, and abdominal, limb, or chest pain) confirmed by imaging.

A number of secondary endpoints were considered. Suspected embolic events were defined as an ‘accidental’ discovery of emboli (ischaemic lesions on a CT scan) after diagnosis of LVT, without any reported symptoms. Transient embolic events were transient ischaemic attack (TIA) defined as a transient neurological deficit without ischaemic lesion on cerebral imaging. Major bleeding was defined as a bleeding event requiring hospitalization and clinically overt major bleeding events, that is, associated with a decrease in the haemoglobin level of ≥2 g/dL, transfusion of ≥2 units of packed red cells or whole blood, involving a critical site (intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, pericardial, intra-articular, intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and retroperitoneal), or related to a fatal outcome. LV reverse remodelling was defined as an increase in LVEF of more than 10% or a decrease in indexed LV end-diastolic diameter or volume of more than 10%.

Case–control dilated cardiomyopathy study

To identify risk factors for LVT in the context of DCM, we matched patients with both LVT and DCM with patients with DCM but without LVT, admitted for the first time to our HF unit between May 2011 and April 2015. Patients were matched for age, sex, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and LVEF measured by TTE. In controls, baseline characteristics, BNP, NYHA class, echocardiographic data at 0 and 6 months, initial MRI data, and all-cause mortality were retrieved from medical files.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The two-tailed significance criterion was set at P < 0.05. Continuous variables are described as mean ± standard deviation or median (first to third quartile). Comparison between groups was performed using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as number (percentage) and compared using χ2 or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Kaplan–Meier method was used to describe the risk for all-cause mortality over time, and survivals were compared using log-rank test.

Results

Description of the study population

Among the 105 included patients, 38 (36%) had a non-ischaemic DCM (Table 1).

| Total (n = 105) | DCM (n = 38) | ICM (n = 67) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 55.9 ± 12.9 | 51.2 ± 14.4 | 58.6 ± 11.2 | <0.01 |

| Male gender, % (n) | 85% (89) | 71% (27) | 92.5% (62) | <0.01 |

| Alcohol abuse, % (n) | 18% (19) | 28.9% (11) | 10% (7) | 0.032 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 23% (24) | 11% (4) | 30% (20) | 0.043 |

| History of hypertension, % (n) | 23% (24) | 11% (4) | 30% (20) | 0.043 |

| History of AF or flutter, % (n) | 6.7% (7) | 2.6% (1) | 9% (6) | 0.42 |

| Previous anticoagulation, % (n) | 10% (11) | 2.6% (1) | 15% (10) | 0.054 |

| History of cancer, % (n) | 11% (10) | 18% (7) | 6% (4) | 0.93 |

| Cha2ds2vasc score, mean ± SD | 2.56 ± 1.27 | 1.78 ± 1.16 | 2.99 ± 1.13 | <0.001 |

| HASBLED score, mean ± SD | 1.41 ± 1.1 | 1.03 ± 0.85 | 1.63 ± 1.17 | <0.01 |

| NYHA 3–4, % (n) | 52% (55) | 76% (29) | 39% (26) | <0.001 |

| Initial cardiogenic shock, % (n) | 16% (17) | 34% (13) | 6% (4) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| BNP (ng/L), median (IQR) | 1795 (377–2559) | 2447 (947–2969) | 1401 (288–1778) | 0.036 |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean ± SD | 79 ± 29.5 | 86.9 ± 36.7 | 74.6 ± 23.9 | 0.075 |

| Blood sodium (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 137 ± 3.2 | 137 ± 3.4 | 137 ± 3.1 | 0.39 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), mean ± SD | 14.4 ± 1.9 | 14.8 ± 1.7 | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 0.091 |

| Haematocrit (%), mean ± SD | 43.4 ± 6.1 | 44.7 ± 5.0 | 42.6 ± 6.5 | 0.074 |

| Platelets (g/L), mean ± SD | 212 ± 81.4 | 211 ± 85.5 | 213 ± 79.7 | 0.91 |

| Leucocytes (g/L), mean ± SD | 8369 ± 3131 | 8327 ± 3235 | 8393 ± 3095 | 0.92 |

| CRP (mg/L), mean ± SD | 30.2 ± 51.6 | 25.8 ± 30.1 | 32.9 ± 61.3 | 0.47 |

| TCA ratio, mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 0.13 | 1.02 ± 0.16 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 0.57 |

| Baseline echocardiographic data | ||||

| TTE LVEF (%), mean ± SD | 25.9 ± 7.7 | 20.8 ± 6.0 | 28.8 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Indexed LVEDD (mm/m2), mean ± SD | 34.0 ± 4.6 | 35.6 ± 4.4 | 32.9 ± 4.5 | <0.01 |

| Right ventricular S′ (cm/s), mean ± SD | 9.5 ± 3.2 | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 9.5 ± 3.1 | 0.87 |

| Estimated SPAP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 42.3 ± 14 | 42.5 ± 14.9 | 42.2 ± 13.5 | 0.82 |

| Baseline cardiac MRI dataa | ||||

| LVEF (%), mean ± SD | 23.1 ± 9.1 | 17.7 ± 5.8 | 27.7 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Indexed LVEDV (mL/m2), mean ± SD | 157 ± 48 | 168 ± 46 | 147 ± 47 | 0.068 |

| MRI RVEF (%), mean ± SD | 32.9 ± 15.1 | 24.1 ± 9.04 | 42.7 ± 14.6 | <0.001 |

- AF, atrial fibrillation; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ICM, ischaemic cardiomyopathy; IQR, inter-quartile range; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; SD, standard deviation; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

- a MRI data available in 72 patients.

The majority (56%) of LVT were diagnosed by TTE (followed by MRI or CT scan), and LVT invisible in TEE was diagnosed with MRI (37%) and CT scan (7%).

Among DCM patients, 27 (71%) were incident HF patients, meaning their cardiomyopathy was diagnosed less than a month ago. Aetiologies of DCM were as follows: idiopathic (N = 19), alcoholic (N = 8), post-chemotherapy (N = 4), non-compaction (N = 2), hereditary with identified mutation (N = 1), Friedreich ataxia (N = 1), Becker myopathy (N = 1), arrhythmia induced cardiomyopathy (N = 1), and post-myocarditis (N = 1).

Among ICM patients, 15 (22%) were incident HF patients (coronary disease diagnosed at the same time as the LVT). In prevalent patients (78%), mean delay between ICM diagnosis and LVT was 6.3 years.

Mean age at diagnosis of LVT was 55.9 ± 12.9 years, and most patients were male (85%) (Table 1). DCM patients were significantly younger (51.2 ± 14.4) than ICM patients (58.6 ± 11.2, P < 0.01, Table 1). Diabetes and hypertension were more frequent in ICM patients, whereas alcohol abuse was more frequent in DCM patients. ICM patients had a higher HASBLED score, in relation with a higher proportion of anti-platelet agents, and a higher CHA2DS2VASC score. NYHA class was higher in DCM patients than in ICM patients (76% vs. 39% NYHA 3–4, P < 0.001). DCM patients had more severe initial presentations (cardiogenic shock 34% in DCM vs. 6% in ICM, P < 0.001), higher BNP values (2447 vs. 1401 ng/L), and lower LVEF (21 ± 6% vs. 29 ± 8%, P < 0.001, Table 1). LVT had an apical localization in a vast majority of cases (98 patients, 93% of cases).

One year prognosis of left ventricular thrombus

During the first year, the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality and/or symptomatic embolic event occurred in 20% of patients (Figure 1), all-cause mortality in 5.7%, and CV mortality in 4.8% (five patients—four due to a cardiogenic shock and one to massive ischaemic stroke). One patient died from a non-CV cause during the first year (septic shock). The 1 year risks for these outcomes were not significantly different in ICM and DCM patients (primary endpoint P = 0.96; all-cause mortality P = 0.41).

Symptomatic embolic events occurred in 15% of patients (Figure 1). No DCM patient had disabling stroke (two had a complete recovery, one had a slight dysarthria, and none underwent thrombolysis therapy). Among ICM patients, one limb ischaemia lead to amputation, one had toe necrosis, all others underwent Fogarty procedure without complications, and two strokes had disabling consequences.

Suspected or transient embolic events occurred in 13% of patients, significantly more frequently in DCM patients (29% in DCM vs. 4.5% in ICM, P < 0.01). Major bleeding event rates were not significantly different across groups.

All reported symptomatic embolic events occurred during the first 30 days following the diagnosis of LVT. No significant difference was seen when comparing incident with prevalent subgroups.

Long-term prognosis of left ventricular thrombus

During a median follow-up of 8.7 years, all-cause mortality occurred in 11 patients (10%) and was not significantly different in DCM and ICM (P = 0.63, Figure 2). Six patients died from cardiogenic shock, one from ventricular arrhythmia, one from ischaemic stroke, one from intracerebral bleeding, and two from septic shock.

We did not record any other embolic event during long-term follow-up (i.e. after the first year) attributed to an LVT.

Evolution and reverse remodelling

Left ventricular reverse remodelling was observed in most patients after 12 months and was more frequent in DCM than in ICM patients (86% vs. 54% respectively, P = 0.02, Table 2). One year after diagnosis of LVT, DCM patients had higher LVEF (40.2% vs. 33.9%, P = 0.04), lower BNP (195 vs. 596 ng/L, P < 0.01), but not significantly different hospitalization rates.

| Total (105) | DCM (n = 38) | ICM (n = 67) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging findings | ||||

| LV positive remodelling (n = 68), % (n) | 65% (44) | 86% (19) | 54% (25) | 0.02 |

| TTE LVEF at 12 months (%), mean (±SD) | 35.9 ± 11.1 | 40.2 ± 13.5 | 33.9 ± 9.3 | 0.04 |

| RV S′ at 12 months (cm), mean (±SD) | 11.2 ± 2.9 | 11.8 ± 3.4 | 10.9 ± 2.6 | 0.30 |

| BNP at 12 months (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 460 (68–528) | 195 (25–204) | 597 (101–797) | 0.01 |

| HF outcomes | ||||

| Hospitalization for HF within the 1st year, % (n) | 9.4% (8) | 3.3% (1) | 13% (7) | 0.25 |

| Hospitalization for HF during follow-up, % (n) | 21% (18) | 21% (6) | 22% (12) | 1 |

| LVT evolution (n=84) | ||||

| Confirmed LVT disappearance, % (n) | 58.1% (51) | 76.3% (29) | 47.8% (32) | 0.01 |

| Confirmed LVT persistence, % (n) | 14.3% (15) | 2.6% (1) | 20.9% (14) | 0.02 |

| Doubtful LVT persistence, % (n) | 5.7% (6) | 2.6% (1) | 7.5% (5) | 0.41 |

| Death before LVT disappearance, % (n) | 2.9% (3) | 2.6% (1) | 3.0% (2) | 1 |

| Missing data, % (n) | 8.6% (9) | 7.9% (3) | 9.0% (6) | 1 |

- BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; ICM, ischaemic cardiomyopathy; IQR, inter-quartile range; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVT, left ventricular thrombus; RV, right ventricular; SD, standard deviation; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

The 1 year LVT disappearance occurred in most patients, more frequently in DCM than in ICM (76.3% of LVT disappearance vs. 47.8%, respectively, P < 0.01, Table 2). Among all patients, seven underwent LVT surgery or heart transplantation within the first year after diagnosis; three died while still having LVT and LVT's persistence or disappearance was doubtful for six patients. Data were missing for nine patients (loss to follow-up, absence of imaging at 1 year, or available TTE of poor quality).

Risk factors and impact on prognosis of embolic events

There was no significant difference for baseline characteristics between patients with symptomatic embolic events (N = 16) and without symptomatic embolic events (Supporting Information, Table S1). Mortality during follow-up, hospitalization rate for HF, and LV remodelling rates were not different among groups. Patients with or without the primary endpoint also had similar baseline characteristics (Supporting Information, Table S2).

Management of left ventricular thrombus

A minority of patients (4.8%) underwent surgery for LVT: two DCM patients with suspected cerebral embolic events (asymptomatic ischaemic lesions on a CT scan) had no size reduction of a mobile LVT in spite of anticoagulant treatment for >5 days; one ICM patient had a symptomatic kidney ischaemia and a voluminous and mobile residual LVT; one ICM patient had a voluminous LVT (maximum size 44 mm) and a TIA; and one ICM had coronary artery bypass and ventricle aneurysm resection at the same time.

The vast majority of patients (97.1%) received anticoagulant treatment (Figure 1, vitamin K antagonists in all cases). One DCM patient did not receive anticoagulant treatment because of concomitant major bleed and two ICM patients because of a very high estimated bleeding risk.

Anticoagulant treatment was maintained for more than 1 year in 80% of cases (66/81 patients with available data) and was more frequent in ICM than in DCM (87.5% vs. 65.4%, P = 0.04, Figure 1). The majority (13/15) of patients in whom anticoagulation was stopped had clinically significant reverse remodelling.

Ischaemic cardiomyopathy patients were more likely to receive anti-platelet therapy and underwent implantable defibrillator implantation more frequently (Figure 1).

Risk factors of left ventricular thrombus in dilated cardiomyopathy

In our case–controls study, DCM patients with LVT were matched for age, sex, NYHA class, and LVEF with a cohort of 38 DCM patients without LVT. Patients with and without LVT had no significant differences in the proportion of diabetes and smoking, biological profile, and TTE/MRI characteristics. However, we found a significantly higher BNP level in patients with LVT (2447 ng/L, inter-quartile range 947–2969 vs. 347 ng/L, inter-quartile range 220–413, P < 0.001, Supporting Information, Table S3).

Discussion

Our study provides a detailed description of HF patients diagnosed with LVT. Our main finding is that 1 year rate of events is sizable despite anticoagulant treatment (15% for embolic event and 5% for CV mortality). Of uttermost importance, all symptomatic events occurred within 30 days of LVT diagnosis. We also show that most patients with DCM will experience reverse remodelling (86% at 12 months). Despite the fact that DCM patients had more severe HF (as evidenced by higher BNP level, higher NYHA class and lower LVEF), their rate of embolic events was similar to those experienced by ICM patients.

Patients with HF have significant rates of embolic events, even in the absence of atrial fibrillation. The meta-analysis5 of four relevant prospective randomized controlled trials,6-9 including patients with HF with reduced LVEF in sinus rhythm, showed no significant reduction in the risk of all-cause death when taking warfarin vs. aspirin. However, warfarin significantly reduced the risk of stroke (fatal and non-fatal ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes—relative risk of 0.59). Yet the recent large-scale COMMANDER-HF trial reported a neutral effect of rivaroxaban in ischaemic HF with reduced ejection fraction in sinus rhythm.10 Oral anticoagulation is consequently currently not indicated for patients with HF with reduced LVEF in the absence of atrial fibrillation. However, in a post hoc analysis of COMMANDER-HF, rivaroxaban significantly reduced by 32% the occurrence of all-cause strokes or TIA compared with a placebo.11 This observation suggests that some patients could still benefit from an anticoagulant therapy, possibly when at high risk of LVT. For example, patients with non-compaction are known to have a propensity for thrombus formation and embolic events, and they may be candidates for lifelong anticoagulation even in the absence of thrombus. In addition, the occurrence of LVT is an indication for anticoagulants in HF.

To our knowledge, our study is the largest contemporary cohort describing the clinical profile and outcomes of patients with LVT in HF. Several studies before the MRI era tried to determine prevalence and embolic potential of LVT in HF of various etiologies12 or in few patients with non-ischaemic DCM.13 Surprisingly, these studies did not find convincing association between LVT and the occurrence of embolic events.14, 15 In contrast, we report herein that non-ischaemic DCM patients with an LVT have a high rate of embolic events within 30 days of diagnosis (possibly because routine follow-up imaging was unable to identify thrombus prior emboli). However, these patients have few long-term consequences (death <3%, no disabling stroke) and a good recovery potential with 86% of patients experiencing 12 month reverse remodelling. Surprisingly, the only risk factors of LVT we identified in our dedicated case–control study are high BNP value. Importantly, other markers of severity and/or remodelling, not measured in our study, could also be predictive of LVT occurrence. More detailed evaluations could shade a new light on the LV morphological and functional determinants of LVT, possibly using MRI. Yet our paper indicates that a simple integrative marker (BNP) may be associated with LVT risk.

Our clinical management indicated LVT surgery only in extreme circumstances. In our view, patients with severely reduced LVEF who undergo surgical thrombectomy are exposed to significant perioperative complications and high mortality. These patients may be precipitated towards LV assist device implantation or heart transplant after cardioplegia, with a high risk of organ failure due to ischaemic injury. The consequence of this surgical approach may be unpredictable as the vintage (and subsequent stability) of the thrombus is by nature unknown and may largely depend on the frequency of echocardiographic follow-up of patients. As a consequence, if no other emergent surgical procedure is indicated, our results call for a cautious management as the risk–benefit balance might not favour initial LVT surgery. Our ‘wait-and-see’ approach seems to perform well in light of the low mortality rate of our cohort.

Clinical perspectives

Our results suggest that LVT is associated with a significant rate of embolic events, but the presence of LVT or embolic events does not seem to have an important impact on mortality or preclude reverse remodelling under medical treatment. From a clinical standpoint, these results suggest that LVT occurs in clinical situations that are likely to improve rather than in end-stage HF disease. LVT should in no way be perceived as a desperate condition. In addition, based on our report, a ‘wait-and-see’ attitude based on vitamin K antagonist long-term anticoagulation appears as a safe and reasonable management of LVT in HF. Surgery was needed only very rarely in our cohort. Most importantly, the very early phase of LVT management, using anticoagulants, appears of key importance, as symptomatic embolic events occur within 30 days of diagnosis. Importantly, most of the patients in whom anticoagulation was withdrawn after thrombus disappearance had significant reverse remodelling which was perceived to drastically decrease the risk of subsequent thrombus reappearance.

Translational outlook

Our clinical study shows that natriuretic peptides are strongly associated with the presence of LVT. This finding suggests that HF severity is a determinant of the occurrence of LVT. Convincing evidence exist regarding the association of worsening HF with a procoagulant state.16 Yet whether a specific coagulation profile underlies the genesis of LVT is unknown. Dedicated studies should be conducted to better understand this point, possible using a case–control strategy given the frequency of LVT in HF.

Limitations

This retrospective study has several limitations. We may have missed some cases because of clinical files mislabelling. However, this should not introduce significant bias in patients' characteristics. In addition, we could not adequately report thrombus characteristics such as aspect, size, implantation, and mobility, which could all have an impact on the risk of emboli.

Accidental discovery of emboli was considered as an outcome in our study; this can overestimate event risk as other factors of emboli/thrombus (besides LVT) could be the actual cause.

Because of the retrospective design of this study, we did not have access to systematic whole-body imaging searching for asymptomatic systemic embolisms. In addition, it is possible that a systematic use of CMR imaging could have modified the persistence of LV thrombus as it is more sensitive than echocardiography.

This is a single-centre retrospective study, and the number of patients is moderate. Future larger studies should affirm the epidemiological findings related to LVT in the specific setting of HF. Specifically, given the size of our population, we could not investigate the prognostic of LVT among different non-ischaemic DCM aetiologies. These larger studies might identify risk stratifier we were not able to detect because of limited statistical power. These studies should also determine whether regional dyskinesia/aneurism, significant regional contractility abnormalities, and/or fibrosis/morphology as assessed with CMR add to our understanding of LVT onset and prognosis.

The prognosis of LVT could also be different according to thrombus location within the left ventricle; this aspect should be evaluated in future reports.

As vitamin K antagonists remain the reference treatment of LVT, no non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) were used in this study. The prognosis of LVT treated with NOAC remains unknown, but some authors have recently called for their cautious use, because NOACs in patients with LVT were associated with a higher rate of strokes or systemic embolism in a large population of mixed LVT patients with reduced ejection fraction compared with warfarin.17

Conclusion

In conclusion, LVT is associated with a significant rate of embolic events, but the presence of LVT or embolic events does not seem to have an important impact on mortality or preclude reverse remodelling under medical treatment. The occurrence of LVT may be linked to the initial severity of HF as high BNP was a risk factor for LVT. Further investigations are needed to identify other risk factors of LVT and LVT-related embolic events. Meanwhile, a ‘wait-and-see’ attitude based on vitamin K antagonist long-term anticoagulation appears as a safe and reasonable management of LVT in HF. In all cases, as symptomatic embolic events occur within 30 days of diagnosis, a very careful initial management is warranted.

Conflict of interest

N.G. received honoraria from Novartis, AstraZeneka, Vifor and Boehringer.

Funding

None.