The multiple faces of autoimmune/immune-mediated myocarditis in children: a biopsy-proven case series treated with immunosuppressive therapy

Abstract

The role of immunosuppressive therapy (IT) in paediatric autoimmune/immune-mediated myocarditis remains poorly defined. To explore its role, we present a series of three consecutive paediatric patients with biopsy-proven, virus negative, autoimmune/immune-mediated myocarditis, with distinct clinical and pathological features, who have been successfully treated with IT, a 14-year-old boy with Loeffler's fibroblastic parietal endomyocarditis, a 6-year-old child with celiac disease with chronic active lymphocytic myocarditis, and a 13-year-old boy with long-standing heart failure and active lymphocytic myocarditis. Patients started IT and entered follow-up between July 2017 and September 2019; the first patient completed IT. IT was associated with a substantial and sustained recovery of cardiac function in our patients, regardless of their heterogeneous clinical and pathological features. Combination IT was well tolerated and enabled tapering and weaning off steroids.

Introduction

Myocarditis, an inflammatory disease of the myocardium caused by infectious and non-infectious causes, may affect children and cause sudden cardiac death and progression to dilated cardiomyopathy.1-3 Paediatric myocarditis (PM) can present with non-specific systemic, gastrointestinal and respiratory prodromes; infarct-like and fulminant presentations are common.2 The role of immunosuppressive therapy (IT) for autoimmune/immune-mediated PM remains controversial.4-6 We present three consecutives patients with biopsy-proven, virus negative PM, with distinctive clinical and pathological features, who have been successfully treated with IT.

Case Report

Patient 1

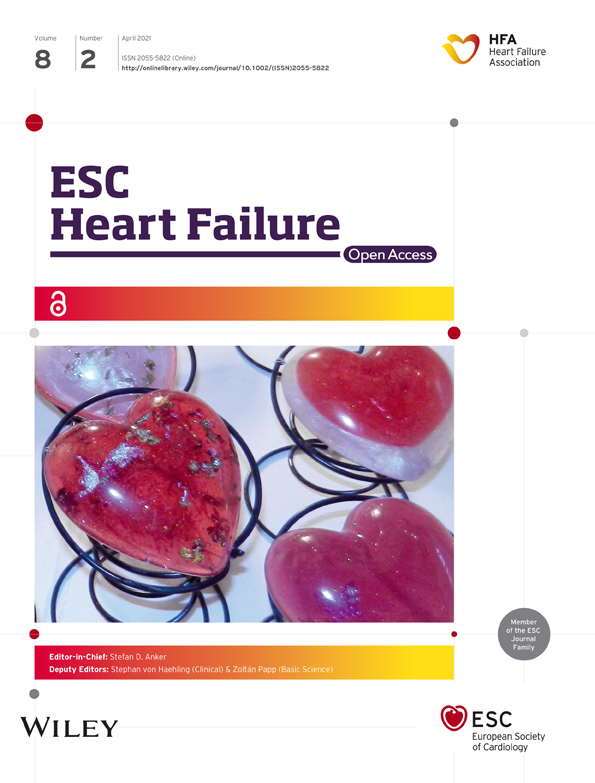

In January 2017, a 14-year-old boy, with no history of allergy/asthma, was hospitalized for recent onset of fever, acute chest pain, and weakness. Blood tests showed persistent and unexplained hypereosinophilia (8410/mL), high troponin I (19 000 ng/L), and N-terminal-pro-b-type-natriuretic-peptide (NT-proBNT, 300 ng/L). Chest X-ray (CXR) showed bilateral pleural effusion and 12-lead-electrocardiogram (ECG) inverted infero-lateral T waves; 2D echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) showed patchy mid-wall-subendocardial oedema of the posterior and anterolateral walls, involving papillary muscles, and concomitant patchy late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). Heart failure (HF) symptoms, troponin release, and hypereosinophilia persisted on optimized medical therapy; a complete microbiological, immunological, and onco-haematological work-up ruled out specific hypereosinophilic syndromes. Because primary eosinophilic myocarditis is associated with a dismal cardiac outcome and responds to IT,1, 3, 7 endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) was performed, revealing virus negative, Loeffler's fibroblastic endomyocarditis (Figure 1). After excluding contraindications, he was started on i.v. methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kg/day, then switched to oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day, with a regression of symptoms, peripheral eosinophilia, pleural effusions, as well as normalization of troponin, NT-proBNT, and ECG. Methotrexate, 7.5 mg/week p.o., was added as steroid sparing agent, due to positivity for thiopurine-methyl-transferase mutations, which contraindicated the use of azathioprine. In November 2017, a second EMB was scheduled to check efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy, because myocarditis can persist in spite of no symptoms, and to confirm the absence of occult opportunistic infection, and it showed healed myocarditis with interstitial fibrosis and no opportunistic infections. Within 2 years, IT was tapered and discontinued; at the last follow-up in February 2020, his clinical condition, ECG, echocardiogram, and laboratory tests remain steadily normal.

Patient 2

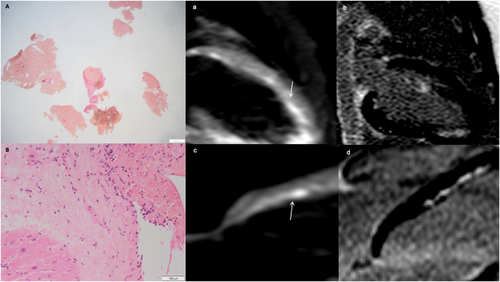

In 2018, a 6-year-old child with a 6 month history of weight loss, recurrent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, dyspnoea, and fatigue was admitted to our Paediatric Cardiology Unit where he started a conventional HF treatment. The patient had positive (144 000 kU/L; n.r. <7 kU/L) anti-tissue transglutaminase, anti-endomysial and anti-deamidated-gliadin peptides IgG antibodies, HLA-DQ2 positivity, and hypochromic anaemia. Inflammatory markers, renal, liver, and thyroid function tested normal. A diagnosis of celiac disease (CD) was made, and a gluten-free diet was started. CXR showed cardiomegaly and vascular congestion; ECG showed poor precordial R-wave progression and low QRS voltages. Echocardiography showed a severely dilated left ventricle (LV), reduced LVEF (21%), mitral regurgitation, and dilated right ventricle (RV). NT-proBNP was 26 000 ng/L; 24 h Holter ECG showed no arrhythmias. Immunofluorescence for organ-specific anti-heart autoantibodies (AHA) and anti-intercalated-disk (AIDA) autoantibodies tested positive.8-10 CMR showed remarkable LV dilatation, severely impaired LVEF (27%), dilated RV, myocardial oedema, and subendocardial fibrosis. In order to clarify the aetiology of his cardiomyopathy, the patient underwent cardiac catheterisation and EMB, which showed chronic active myocarditis, with necrosis and replacement fibrosis; the search for viral genomes was negative (Figure 2). Due to recurrent HF episodes on optimal medical therapy, including inotropic support, after testing negative for thiopurine-methyl-transferase mutations, he was started on i.v. methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kg/die, then shifted to oral prednisone, 25 mg o.d., in combination with oral azathioprine, 50 mg/day. Serial echocardiographic follow-up showed progressive improvement of biventricular size and LVEF increased to 57%. After 12 months, steroids were discontinued, gastrointestinal symptoms disappeared, somatic growth and clinical condition and LVEF returned to normal; he is still on IS with azathioprine and a low-dose angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, pending a scheduled follow-up EMB to assess histological resolution of myocarditis.

Patient 3

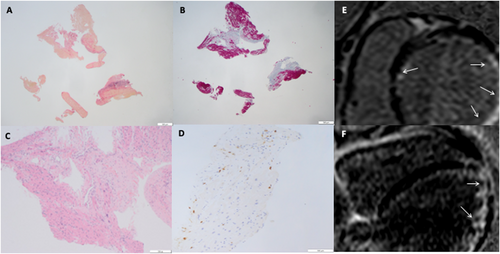

In 2015, a 9-year-old child was hospitalized for chest pain, palpitations, and fatigue. Blood tests showed negative troponin, normal renal, liver, thyroid function, and inflammatory markers. CXR showed cardiomegaly and pulmonary vascular congestion; ECG showed left bundle branch block (LBBB); echocardiography revealed severely dilated left ventricle (LV) with global hypokinesia and an LVEF of 18%, moderate functional mitral regurgitation and left atrial dilatation; NT-proBNP was 5000 ng/L. CMR confirmed a severely dilated and dysfunctional LV (LVEF 20%) with global hypokinesia and interventricular desynchrony but no myocardial oedema or fibrosis. Exercise tolerance test showed reduced functional capacity and exercise-induced LBBB; 24 h Holter ECG excluded ventricular arrhythmias. At serial echocardiographic follow-up, he remained stable on New York Heart Association class II, with severely dilated LV and systolic dysfunction, LBBB and elevated NT-proBNP levels (4000 ng/L) on standard heart failure medications. Four years later, he was again hospitalized for recurrent dyspnoea and oliguria. He had a severely dilated and hypokinetic LV, with a LVEF of 9%, persistent LBBB and a NT-proBNP of 11 000 ng/L. He was immediately admitted to paediatric ICU, ino-dilator drugs, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, and maximal conventional therapy for decompensated acute-on-chronic heart failure were started, including two courses of levosimendan. Following collegial discussion with the paediatric cardiac surgeons, a haemodynamic study was planned to assess a possible indication to ventricular assist device (VAD) implant, as a bridge to heart transplantation. Cardiac catheterization showed post-capillary pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure 34 mmHg, wedge pressure 26 mmHg) with elevated pulmonary vascular resistance index (4.3 UW/m2) and low cardiac output (1.88 L/min/m2). EMB revealed virus negative, active lymphocytic myocarditis, cardiomyocyte necrosis, and replacement fibrosis (Figure 3). AHA and AIDA tested positive. He was then started on i.v. methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kg/die, then shifted to oral prednisone, 50 mg o.d. Within a month, echocardiography showed gradual improvement of LVEF (33%) and NT-proBNP dropped to 400 ng/L. Three months later, LVEF improved to >40%, NT-proBNP returned to normal range, and LBBB resolved. A follow-up catheterization 5 months apart showed clear-cut improvement of mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP, 24 mmHg,) pulmonary artery wedge pressure (7 mmHg), pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI, 4.8 UW/m2) and cardiac output (3.95 L/min/m2). After testing negative for thiopurine-methyl-transferase mutations, azathioprine, 2 m/kg/day, was added enabling prednisone tapering. A third catheterization in July 2020 showed the normalization of PAP, PVRI, and LVEF (59%) and a persistent myocardial inflammation at EMB; LBBB disappeared on ECG, and he is still on IS.

Discussion

Immunosuppressive therapy was associated with a substantial and sustained recovery of cardiac function in our patients, regardless of heterogeneous clinical and pathological features. The possibility that improvement of cardiac function derives from HF medications, particularly in Cases 2 and 3, seems highly unlikely, because both had long-standing heart failure symptoms and LV dysfunction and were deteriorating in spite of optimized HF medications and were under consideration for heart transplant listing. Combination IT was well tolerated and enabled tapering and weaning off steroids. Knowledge about IT in PM is limited. A recent meta-analysis, mostly based on a clinically suspected, not biopsy-proven diagnosis, reported a significant improvement of LVEF along with a reduction of left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter and of risk of death and heart transplant after IT; the benefit seemed even more significant in children with an EMB proven diagnosis.6 Azathioprine in combination with prednisone proved effective in the treatment of adult lymphocytic virus-negative myocarditis.11 We administered combined IT; in children, steroids should be used at lower cumulative dosages and for shorter periods, to reduce their impact on body growth. In Patient 1, methotrexate was preferred due to a thiopurine-methyl-transferase mutation that may cause severe leukopenia-agranulocytosis on azathioprine therapy.12 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported paediatric case of primary eosinophilic myocarditis successfully treated with methotrexate and corticosteroids.7 The remaining two thiopurine-methyl-transferase-negative patients, with a lymphocytic virus-negative myocarditis, showed an excellent tolerance to azathioprine. We did not use intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG). IVIG did not show efficacy in biopsy-proven virus-negative autoimmune myocarditis and should be used in specific forms of virus-positive myocarditis, that is, Parvovirus-B19 associated.1 Patient 2 had concomitant severe CD, which may be linked to pericardial and myocardial inflammation.13, 14 Following IT and gluten-free diet, he obtained a complete remission of gastrointestinal symptoms with a remarkable recovery of body growth and quality of life. Interestingly, Patient 3 showed a complete recovery of LVEF and LBBB disappearance following IT, despite a prolonged history of undiagnosed myocarditis. This suggests a long window of opportunity to reach reverse LV remodelling in PM. It is conceivable that in this young patient, the myocardium was recovered from his ‘immunological stunning’ with the resolution of inflammation, in spite of a long-lasting myocardial dysfunction. This case raises new pathogenetic hypotheses to understand myocardial impairment in autoimmune/immune-mediated PM, which may imply a greater plasticity and a wider time window for therapeutic intervention before myocardial changes become irreversible. It is possible that paediatric patients with myocarditis have greater chances of cardiac function recovery even in presence of replacement fibrosis at EMB, important severe LV remodelling and long duration of LV dysfunction. Thus, great efforts have to be made in identifying the aetiology of LV dysfunction in children (also through histological evaluation). EMB is a procedure at potential risk of major complications particularly in small children and is recommended in case of high-risk presentations, when the procedure might affect the prognosis of the patient.1-3 All three cases are in keeping with such indication. In Case 1, peripheral idiopathic hypereosinophilia suggested Loeffler's endomyocarditis, associated with a dismal prognosis. Case 2 had refractory heart failure with severely reduced ejection fraction in spite of optimal heart failure medication and a gluten-free diet. Case 3 had long-standing refractory heart failure with critically reduced LVEF and worsening symptoms. In general, EMB should not be repeated in asymptomatic patients with stable, recovered clinical conditions; however, in keeping with the ESC 2013 position paper reco's, it may be considered in selected patients to monitor response to aetiology-directed therapy.1

For optimal clinical risk management, EMB and IT should always be carried out in expert settings. IT may lead to complications (i.e. severe opportunistic infection); thus, it should be administered after exclusion of possible contraindications and with the aware collaboration and therapeutic education of the patients and/or their parents/caregivers.15 Last but not least, these patients need tight follow-up.

Ethics statement

Our study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, the locally appointed Ethics Committee has approved the research protocol, and informed consent has been obtained from the parents of the children.

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE disclosure form and declare no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Funding

Nothing to declare.