Heart failure epidemiology and treatment in primary care: a retrospective cross-sectional study

Abstract

Aims

Heart failure is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, but little is known on heart failure epidemiology and treatment in primary care. This study described patients with heart failure treated by general practitioners, with focus on drug prescriptions and especially on the only specific treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, namely sacubitril/valsartan.

Methods and results

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study using data from an electronic medical record database of Swiss general practitioners from 2016 to 2019. Multilevel logistic regression was used to find determinants of sacubitril/valsartan prescription; odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. We identified 1288 heart failure patients (48.5% women; age: median 85 years, interquartile range 77–90 years) by means of diagnosis code, representing 0.5% of patients consulting a general practitioner during the observation period. About 73.6% received a renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitor, 67.8% a beta-blocker, 34.6% a calcium channel blocker, 86.1% a diuretic, and 40.1% another cardiac drug. Sacubitril/valsartan was prescribed in 6% predominantly male patients (OR 2.10, CI 1.25–3.84), of younger age (OR 0.59 per increase in 10 years, CI 0.49–0.71), with diabetes mellitus (OR 1.76, CI 1.07–2.90). The recommended starting dose for sacubitril/valsartan was achieved in 67.1% and the target dose in 28.6% of patients.

Conclusions

Prevalence of heart failure among patients treated by general practitioners was low. Considering the disease burden and association with multimorbidity, awareness of heart failure in primary care should be increased, with the aim to optimize heart failure therapy.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide and one of the most common reasons for hospitalization.1, 2 The estimated lifetime risk of developing HF is about 20%.1 Still, little is known on HF epidemiology and its treatment in primary care.

Heart failure is often accompanied by comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and atrial fibrillation. Based on the HF patient's ejection fraction, HF can be classified into HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

For patients with HFrEF, several pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options are available to improve quality of life and prognosis.3 The most important pharmacological treatments for HFrEF include renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, that is, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, as well as beta-blockers and diuretics. Sacubitril/valsartan, the only currently available angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, has been approved in Switzerland, Europe, and the USA in 2015 and is recommended for HFrEF patients remaining symptomatic despite treatment with ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.4 Sacubitril/valsartan is only approved for the treatment of HFrEF.

For patients with HFpEF, no therapies have been shown to improve morbidity or mortality.5-10 Treatment for HFpEF is generally guided by improving hypertension and/or relieving symptoms of the underlying entity, meaning that any combination of the available cardiac therapies can be used individually.

Primary care physicians, that is, general practitioners (GPs), play an important role in the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of HF patients.11-16 Hence, data from primary care about epidemiology and treatment of HF are of high interest. In this study, we therefore described characteristics, monitoring, and treatment of HF patients in Swiss primary care in detail, with focus on the only specific HFrEF therapy, namely sacubitril/valsartan.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

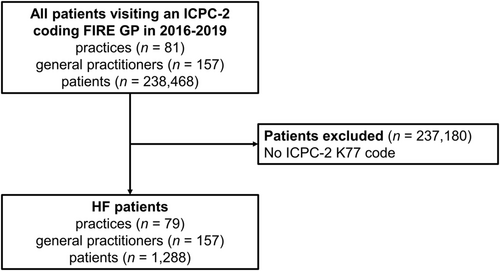

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional study based on Swiss primary care data from the FIRE project.17 FIRE stands for Family medicine International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) Research using electronic medical records (EMRs). The FIRE project collects anonymized routine data from EMR of currently over 400 contributing GPs. For each consultation, age and sex of the patient, issued medication prescriptions, and values of laboratory and vital sign measurements are recorded. Some GPs also provide ICPC Second edition (ICPC-2) diagnosis codes. For this study, we only considered patients who had a consultation in 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2019 with a GP who ever used the ICPC-2 code K77 (explicit HF diagnosis) and included patients with an ICPC-2 code K77. An overview of the patient selection process is given in Figure 1.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The local Ethics Committee of the Canton of Zurich approved studies within the FIRE project (BASEC-Nr. Req-2017-00797) and waived the requirement to obtain patients' informed consent because the FIRE project is outside the scope of the Human Research Act.18

Database query, variables, and definitions

We extracted data on GP and patient level. From GPs, we extracted sex and year of birth. From patients, we extracted sex, year of birth, presence of comorbidities (hypertension, moderate or severe chronic kidney disease, obesity, history of myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, and atrial fibrillation), and their last consultation date in the observation period. Comorbidities were defined based on ICPC-2 code, medication, or laboratory/vital values, as specified in Supporting Information, Table S1. Additionally, for each patient, we extracted the following information of the 12 months before their last consultation: number of consultations; drug prescriptions belonging to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification group C (cardiovascular system) except vasoprotectives and lipid-modifying agents,19 including dosing schemes and dosage per pill for drugs with defined target doses according to the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF3; and number and last value of relevant laboratory measurements and vital signs [potassium; creatinine; brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) variants including BNP, NT-proBNP, or proBNP; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; heart rate; and weight]. Sacubitril/valsartan starting dose and target dose achievement were calculated based on the minimal value specified in the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF.3

Objectives

This study aims to describe HF patients treated by GPs (i.e. their characteristics, detailed drug therapy, monitoring, and clinical values), to describe HF patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan, to find determinants of sacubitril/valsartan prescription, and to assess sacubitril/valsartan starting and target dose achievement rates.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the R software version 3.5.1.20 To describe the data, we reported counts (n) and proportions (%) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). For group comparisons, we used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, χ2 tests, or Poisson regression, as appropriate, and reported P values. Significance was assumed for P values < 0.05. Missing data were left unchanged. We performed multilevel logistic regression to investigate the odds of sacubitril/valsartan prescription, adjusting for random GP effects, including the following pre-specified predictors: patient age and sex, presence of diabetes mellitus and obesity, GP age and sex, and year of observation (to account for lead time after sacubitril/valsartan approval). Continuous variables were standardized. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

Results

Description of general practitioners, heart failure patients, and patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan

We characterized 1288 HF patients of 157 different GPs, representing 0.5% of all patients with a consultation in 2016–2019.

General practitioners were 54 (median, IQR 45–61) years old and 45.2% (n = 71) were women. On average (median), they treated two (IQR 1–6) HF patients in 2016–2019.

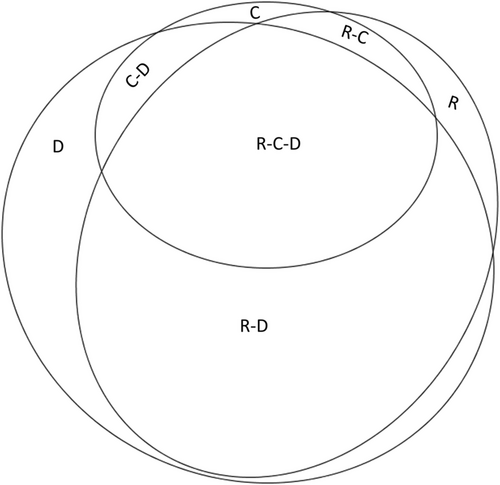

Characteristics and treatment of HF patients, including comorbidities, drug therapy, monitoring, and laboratory and vital parameter values are given in Table 1. Of the 1288 patients, 73.6% received an RAAS inhibitor, 67.8% a beta-blocker, 34.6% a calcium channel blocker, 86.1% a diuretic, and 40.1% another cardiac drug therapy. Treatment combinations of RAAS inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics are shown in Figure 2.

| Variable | All HF patients (n = 1288) |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Median age (IQR) | 85 (77–90) |

| % female | 48.5 |

| Comorbiditiesa | |

| % with atrial fibrillation | 31.7 |

| % with severe chronic kidney disease | 12.3 |

| % with moderate chronic kidney disease | 40.9 |

| % with diabetes mellitus | 33.0 |

| % with myocardial infarction | 2.5 |

| % with obesity | 32.7 |

| % with hypertension | 56.8 |

| % with any of the above | 87.7 |

| Drug therapy | |

| Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors | 73.6 |

| % with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 49.5 |

| % with angiotensin II receptor blockers | 32.8 |

| % with angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor | 6.0 |

| % with renin inhibitors | 0.6 |

| Beta-blockers | 67.8 |

| Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) | 34.6 |

| % with selective CCB with mainly vascular effects | 32.7 |

| % with selective CCB with direct cardiac effects | 3.2 |

| Diuretics | 86.1 |

| % with thiazides | 10.7 |

| % with low-ceiling diuretics, excl. thiazides | 14.8 |

| % with high-ceiling diuretics | 77.8 |

| % with potassium-sparing agents | 32.6 |

| % with unspecific diuretics (combination therapy) | 23.1 |

| Cardiac therapy | 40.1 |

| % with cardiac glycosides | 8.9 |

| % with antiarrhythmics, class I and III | 15.2 |

| % with cardiac stimulants | 1.1 |

| % with vasodilators used in cardiac disease | 21.3 |

| % with other cardiac preparations, including ivabradine | 4.4 |

| Others | |

| % with peripheral vasodilators | 0.8 |

| % with other antihypertensivesb | 3.0 |

| Monitoring | |

| Median number of consultations/year (IQR) | 17 (9–29) |

| Measurements | |

| % with potassium measurement | 47.1 |

| % with creatinine measurement | 74.6 |

| % with BNP variantc measurement | 7.6 |

| % with blood pressure measurement | 76.4 |

| % with heart rate measurement | 72.5 |

| % with weight measurement | 51.0 |

| Clinical values | |

| Median potassium (IQR) (mmol/L) | 4.3 (4.0–4.6) |

| Median creatinine (IQR) (μmol/L) | 101 (80–131) |

| Median systolic blood pressure (IQR) (mmHg) | 129 (114–140) |

| Median diastolic blood pressure (IQR) (mmHg) | 74 (65–81) |

| Median heart rate (IQR) (beats/minute) | 73 (64–83) |

| Median weight (IQR) (kg) | 74 (62–87) |

- BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; HF, heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; proBNP, pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

- For each patient, the 12 months before their last consultation within the observation period are described. Note that drugs are not necessarily simultaneously co-prescribed, as they represent all medication prescribed within the 12 months. Comorbidities were defined based on ICPC-2 code, medication or laboratory/vital values, as specified in Supporting Information, Table S1.

- a Definitions of comorbidities can be found in Supporting Information, Table S1.

- b ATC group C02.

- c BNP, NT-proBNP, or proBNP.

Of all HF patients, 6.0% (n = 77) valsartan/valsartan (Supporting Information, Table S2). These patients were considerably younger (median 75 years, IQR 64–82 years, OR 0.59 per increase in 10 years, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.71), more often men (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.25 to 3.84), and had more often diabetes mellitus (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.90) than HF patients without sacubitril/valsartan (for OR of all predictors including 95% CI and P values, see Supporting Information, Table S3). Besides, sacubitril/valsartan patients showed higher consultation rates, creatinine levels, and weight, but lower heart rate and blood pressure values, compared with HF patients without sacubitril/valsartan (Supporting Information, Table S2).

Description of substances

Overall, the 1288 HF patients had 5673 drug prescriptions within the selected drug groups. As some were prescriptions for combination products, the total number of prescribed substances amounted to 6242. The number of prescriptions of each substance, that is, generic name, is shown in Table 2. The most frequently prescribed substance was a diuretic, namely, torasemide (968 prescriptions). Within drug groups, the most frequently prescribed substances were lisinopril (55.5% of ACE inhibitor prescriptions), valsartan (37.5% of angiotensin II receptor blocker prescriptions), metoprolol (36.8% of beta-blocker prescriptions), amlodipine (79.8% of calcium channel blocker prescriptions), torasemide (43.2% of diuretic prescriptions), and glyceryl trinitrate (27.3% of cardiac therapy product prescriptions).

| Number of prescriptions (%a within drug group) | Recommended daily doseb: starting-target (mg) | Median prescribed daily dose (IQR, % missing) (mg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | 850 (100%) | ||

| Lisinopril | 472 (56%) | 2.5–20 | 10 (5–20, 5.3%) |

| Perindopril | 160 (19%) | - | - |

| Ramipril | 156 (18%) | 2.5–10 | 5 (2–5, 3.2%) |

| Enalapril | 51 (6%) | 5–20 | 20 (10–20, 11.8%) |

| Othersc | 11 (1%) | - | - |

| ARBs | 608 (100%) | ||

| Valsartan | 228 (38%) | 80–320 | 160 (80–160, 29.8%) |

| Candesartan | 212 (35%) | 4–32 | 16 (8–16, 8.0%) |

| Losartan | 74 (12%) | 50–150 | 50 (50–100, 10.8%) |

| Irbesartan | 41 (7%) | - | - |

| Olmesartan medoxomil | 33 (5%) | - | - |

| Othersd | 20 (3%) | - | - |

| ARNIs | |||

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 77 (100%) | 200e-400e | 100 (50–200, 9.1%) |

| Renin inhibitors | |||

| Aliskiren | 10 (100%) | - | - |

| Beta-blockers | 1075 (100%) | ||

| Metoprolol succinate (CR/XL) | 396 (37%) | 12.5–200 | 50 (25–100, 5.1%) |

| Bisoprolol | 377 (35%) | 1.25–10 | 5 (2–5, 6.6%) |

| Nebivolol | 148 (14%) | 1.25–10 | 5 (5–5, 6.8%) |

| Carvedilol | 62 (6%) | 6.25–50 | 19 (12–25, 1.6%) |

| Othersf | 92 (9%) | - | - |

| Calcium channel blockers | 573 (100%) | ||

| Amlodipine | 424 (74%) | - | - |

| Lercanidipine | 44 (8%) | - | - |

| Nifedipine | 33 (6%) | - | - |

| Felodipine | 29 (5%) | - | - |

| Verapamil | 27 (5%) | - | - |

| Diltiazem | 15 (3%) | - | - |

| Diuretics | 2242 (100%) | ||

| Torasemide | 968 (43%) | - | - |

| Spironolactone | 407 (18%) | 25–50 | 25 (25–50, 11.3%) |

| Diuretics, unspecific | 330 (15%) | - | - |

| Metolazone | 146 (7%) | - | - |

| Furosemide | 141 (6%) | - | - |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 125 (6%) | - | - |

| Othersg | 125 (6%) | - | - |

| Cardiac therapy | 746 (100%) | ||

| Glyceryl trinitrate | 204 (27%) | - | - |

| Amiodarone | 187 (25%) | - | - |

| Digoxin | 115 (15%) | - | - |

| Isosorbide dinitrate | 82 (11%) | - | - |

| Nicorandil | 44 (6%) | - | - |

| Othersh | 114 (15%) | - | - |

| Peripheral vasodilators | 10 (100%) | ||

| Ergoloid mesylates | 5 (50%) | - | - |

| Naftidrofuryl | 3 (30%) | - | - |

| Pentoxifylline | 2 (20%) | - | - |

| Other hypertensives | 51 (100%) | ||

| Moxonidine | 16 (31%) | - | - |

| Doxazosin | 13 (25%) | - | - |

| Minoxidil | 6 (12%) | - | - |

| Macitentan | 6 (12%) | - | - |

| Clonidine | 3 (6%) | - | - |

| Othersi | 7 (14%) | - | - |

- ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range.

- Generic names and corresponding numbers, and if available, recommended daily dose and prescribed daily dose, are shown. All generic names with less than 5% share within their drug group were subsumed under ‘others’.

- a Percentages are rounded and may not add up to 100%.

- b For HFrEF, as defined by the 2016 ESC guideline for heart failure.

- c Captopril, quinapril, trandolapril, benazepril, fosinopril.

- d Telmisartan, azilsartan medoxomil.

- e Combined doses for sacubitril plus valsartan.

- f Atenolol, propranolol, sotalol, oxprenolol.

- g Eplerenone, indapamide, thiazides, unspecific, xhlortalidone.

- h Molsidomine, ivabradine, dronedarone, crataegus glycosides, midodrine, etilefrine, flecainide, ranolazine, epinephrine, lidocaine, propafenone.

- i Reserpine, bosentan, riociguat, methyldopa (levorotatory).

For substances with HFrEF disease-modifying effects, the recommended daily starting and target doses3 as well as the median of the actually prescribed dose (IQR) to the study population are given in Table 2. Of patients with sacubitril/valsartan, which represent definite HFrEF patients, 67.1% were prescribed at least the recommended starting dose and 28.6% achieved the recommended target dose (9.0% missing).

Discussion

We studied characteristics and treatment of 1288 HF patients in Swiss primary care, including demographic variables, monitoring and clinical measurements, as well as drug therapy.

In our study, the prevalence of HF among patients visiting a GP was 0.5%. This is low in comparison with other European database studies, where HF prevalence was 1.2–1.3% (Netherlands21 and Italy22). For Switzerland, HF prevalence has been estimated at 2.5%.23 Switzerland is characterized by a high coverage of ambulatory cardiologists,24 which presumably decreases the number of HF patients seen by GPs. Because we relied on explicit coding for HF identification, it is conceivable that we underestimated the prevalence of HF due to inconsistent use of the code by GPs. However, we tried to mitigate this bias by only considering patients of GPs who used at least one HF code.

Nearly half of the HF patients were women, and the average age was 85 years. The sex distribution was similar to other studies,22, 25-27 but the average age was considerably higher.11, 12, 26, 27 This can partly be explained by the different study designs,28 as previous studies were either not based on databases,11, 12, 26 or investigated newly treated patients.27 In addition, younger HF patients are likely treated by ambulatory cardiologists, leaving older HF patients for management by GPs.15, 29, 30 The high patient age of HF patients in our study is noteworthy, as older patients have been consistently underrepresented in landmark HF trials,31 and thus, recommendations for this patient group are scarce.

Because in our data, no information concerning the ejection fraction existed, we were not able to distinguish between HFrEF and HFpEF patients. Therefore, an analysis regarding guideline adherence of the drug therapy was not possible. Nevertheless, the distribution of prescribed medication classes as well as substances suggested awareness for existing guidelines, because diuretics (torasemid) were the most frequently prescribed medication overall, followed by RAAS inhibitor therapy, with lisinopril being the most commonly prescribed substance in this group.32, 33 Depending on comorbidities, there is evidence in favour of certain drug classes vs. others, and also, side effects may influence the choice of therapy. Because atrial fibrillation was highly present in our study population, even the high prescription rates of beta-blockers as the third most common drug group could be regarded as guideline concordant.

The prevalence of patients with sacubitril/valsartan among HF patients in our study was 6%, representing less than half of the proportion reported among HF patients in a US study.34 However, the number in our study needs to be interpreted under the limitation that only HFrEF patients are eligible for sacubitril/valsartan. Considering that according to Hirt et al., approximately half of patients in primary care were HFrEF,12 the proportion of sacubitril/valsartan patients among all HF patients would be comparable. In addition, as discussed above, Swiss GPs might generally see non-severe HF patients as a result of the high availability of ambulatory cardiologists.

We found that sacubitril/valsartan patients were more often men and significantly younger than other HF patient. While sex distribution of these patients was in accordance with previous studies35, 36 and can at least partly be explained by the lower proportion of HFrEF in women,12, 37 age was again considerably increased in this patient group.35, 36 Moreover, we found that sacubitril/valsartan patients more often had diabetes mellitus and a higher weight than the other HF patients. This might be an indication for multimorbid patients having a higher chance of suffering from severe HF, consequently rendering them eligible for sacubitril/valsartan treatment. We observed considerably elevated creatinine levels for sacubitril/valsartan-treated patients, which is both a known side effect of sacubitril/valsartan, as also known for other RAAS blockers, as well as an indication for severity of HF and associated comorbidities.38 Similarly, the low blood pressure observed for sacubitril/valsartan-treated patients (115/68 mmHg) could be a combination of the strong blood pressure-lowering effects of sacubitril/valsartan and the severity of HF leading to sacubitril/valsartan prescription, which is often accompanied by low blood pressure. Lastly, the observed target dose achievement for sacubitril/valsartan (28.6%) was similar to the one observed in a Canadian HF clinic (27.2%)36 but slightly lower than in a study conducted in Swiss primary care (36.5%).39 However, it must be considered that our study was cross-sectional, meaning that some patients might still be in the process of up-titration.

Strengths and limitations

Our study contributes to the understanding of HF epidemiology and treatment in primary care in Switzerland, where information is extremely scarce. GPs were comparable with the average Swiss ambulatory physicians in terms of age and sex.40 Also, our study presumably had high external validity, because in contrast to previous studies, it did not require patient consent or follow-up.41-43

Our study also had some limitations. We had no data on clinical examination or externally performed procedures such as echocardiography, which prevented classification of patients by ejection fraction. In addition, we were dealing with general limitations of database studies, such as missing data or low quality of some data: for some drugs, we only knew when they were started, but not when they were stopped, and changes to the drug dose were sometimes not updated. We therefore tended to overestimate different types of medication prescribed, but underestimate drug doses. Because we could not analyse the free text of the EMR and other non-standardized entries, we might have underestimated diagnoses and monitoring of laboratory measurements and vital signs. Besides, BNP was indistinguishable from NTproBNP in our database, which prohibited interpretation of the value.

Conclusions

Prevalence of HF among patients treated by GPs was low. Nevertheless, considering the disease burden and association with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, awareness of HF in primary care should be raised, aiming at optimal cardiac therapy. The very high median patient age observed for HF patients in primary care calls for recommendations based on studies that include this patient population.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the FIRE study group for participation in the project and providing valuable data from routine care in Switzerland.

Conflict of interest

A.J.F. reports fees from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Fresenius, Imedos Systems, Medtronic, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Vifor, and Zoll. Y.R., R.M., T.R., and C.C. declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by a research collaboration grant of Novartis. The funding had no influence on data inclusion criteria, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.