Green path development: The agency of the City of Vaasa in establishing the battery industry

Correction added on 07 November 2024, after first online publication: The corresponding author's name has been corrected from ‘Okonkwo Ejike’ to ‘Ejike Okonkwo’ in this version.

Abstract

Empirical studies on agency in green path development (GPD) have underexplored non-firm actors' roles. Through a semi-structured interview, this article provides insight into how the City of Vaasa exercises agency toward developing the battery industry and the concomitant effects. The findings reveal that the City of Vaasa provides place-based leadership, for example, through a local-based initiative, that is, the GigaVaasa, as a platform to increase participation and coordinate the actions of public and private actors. As an institutional entrepreneur, they govern the issuance of operating licenses to optimize their economic interest; as innovative entrepreneur, they strategically plan and coordinate infrastructure development to increase the region's attractiveness to external investors and talents. The City of Vaasa agency increases the chances for the region to participate in the global battery market and stimulate the region's economic development. Nonetheless, environmental sustainability concerns remain a profound unintended effect. Conceptually, the article introduces the agency cyclicality and synchronization model to enhance the understanding of the interplay and effect of agency in an emerging green industry's development trajectory.

1 INTRODUCTION

Actors across Europe are responding to the rising need for energy storage solutions to strengthen decarbonization by developing the battery industry (Löfmarck et al., 2022). The sector represents an emerging green path development (GPD) in different regions. By GPD, we mean an industrial development around products, solutions, or technologies that foster sustainability via optimization and conservation of energy and other resources (Sotarauta et al., 2021; UNEP, 2011). Regions could pursue different forms of green paths, for example, path renewal, path diversification, path importation, and path creation (Trippl et al., 2020). The central argument within economic geography literature is that agency is an indispensable factor that drives GPD; agency entails a well-thought-out plan and actions with desirable and undesirable consequences (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Sovacool et al., 2020; Trippl et al., 2020).

Studies show the various ways firm actors exercise agency across sectors. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (2019) and Jolly et al. (2020) argue that firm actors may reinforce or disrupt an existing industrial path. For instance, they play a significant role in developing the Windcluster Mid-Norway (WMN) initiative to foster the transition from the oil and gas industry toward the growth of the wind energy industry (Steen & Karlsen, 2014). An insight into the greening of operations within the shipping, wind, bioeconomy, and biogas industries suggests that firm actors perform innovative entrepreneurial roles through manufacturing and service provision, which contribute to sustaining the existing industries in the region (Sotarauta et al., 2021). Furthermore, private companies such as IKEA were responsible for the innovation and transformation of the furniture industry (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019). Similar studies suggest that incumbent firms contribute to sustaining the pulp and paper industry by deepening specialization and improving energy production and efficiency to remain competitive in the global market (Jolly et al., 2020).

The roles of non-firm actors have also been highlighted, for example, the municipal administration and politicians mobilize financial resources to revitalize and restructure manufacturing industries (Fosse, 2014). Meanwhile, educational institutions jointly participate in networks for exchanging ideas and knowledge to advance GPD (Calignano et al., 2019), while institutional agency is exercised to legitimize, anchor, and enable new paths, for example, in the automotive industry (Miörner, 2020). Likewise, the local and regional authorities provide leadership in supporting the offshore wind industry by facilitating interaction among local and international offshore wind firms (Sotarauta et al., 2021). It is argued that non-firm actors may exercise dynamic agency due to contextual situations, as was the case when the municipalities, influential individuals, and regional development actors became more involved in transforming the pulp industry by mobilizing expertise, providing funding, facilitating the search for and attraction of innovative actors, and reformulating local institutions (Sotarauta et al., 2022).

Our article aims to extend insights into GPD, focusing on non-firm actors' agency toward developing an emerging green path and the effect of such agency. Theoretically, our choice of inspecting non-firm actors' agency is two folds as our paper will be responding to (a) the calls for more empirical studies that uncover what actors are doing in different contexts to support GPD (Asheim et al., 2016; Uyarra et al., 2017). Against the backdrop that the specificity and intricacies of actors' roles differ in every context, regions have different opportunities and utilize various strategies to advance green paths (Grillitsch et al., 2018). In this regard, we assume that actors' agency within the battery industry, which is still underexplored in GPD literature, will manifest in different forms: (b) the calls to go beyond the firm-centric research focus toward more studies on the agency of non-firm actors (Dawley, 2014; Dawley et al., 2015; Tanner, 2014; Trippl et al., 2020).

In our case, we examine how the City of Vaasa exercises agency toward developing the battery industry. For example, its place-based leadership is exercised through a local initiative (GigaVaasa) that serves as a platform for cooperation between the public and private sectors toward achieving a carbon-neutral future. The GigaVaasa comprises the Triple Helix (TH) actors operating in the region, for example, companies, regional authority/development agencies, and educational institutions. The Vaasa region is one of the newest entrants in the Gigafactory enterprise. As Bridge and Faigen (2022) p. 3, observe, the gigafactory refers to a “large-scale facility for lithium-ion battery production in which individual cells are fabricated, combined into battery modules, and (sometimes) assembled as packs for a particular end user.” The industry's development is currently in the planning phase, which includes the construction of infrastructure, such as road networks, as part of the broader strategy to support the industry's future operations; also, negotiation with potential investors is ongoing (VASEK, 2023). In line with Grillitsch and Sotarauta (2019) p. 710, claims that “agency is best studied in its full complexity by situating it in long evolving development processes and structural changes of places,” we think that investigating the agency of the City of Vaasa enables us, in a timely fashion, to capture the proceedings and how they unfold, considering the nascent stage in the industry's development. Thus, our investigation provides an exciting opportunity to understand what actors are doing to foster the green industry.

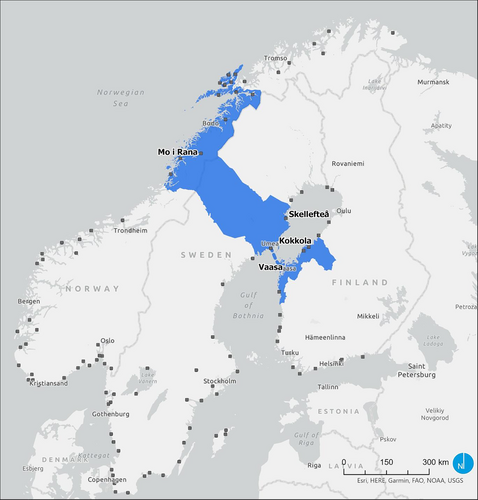

In addition, we chose the Vaasa region due to our familiarity with the context as we consider ourselves insiders with good knowledge of the efforts of the City of Vaasa, which ensures in-depth insight from our study. Focusing on the region facilitates our access to the key stakeholders to participate as respondents, for example, in the semi-structured interviews on how the City of Vaasa exercises its agency. It is imperative to note that being an insider or outside does not confer absolute gains, as both have their downside (Dwyer & Buckle, 2009). On the other hand, our choice of the battery industry is because of its increasing significance in accelerating decarbonization, for example, by supporting e-mobility such as electric cars and electric aviation (cf. Löfmarck et al., 2022; Martins et al., 2021; Okonkwo, 2023). These considerations informed our decision to limit our scope to the Vaasa region instead of inspecting similar regions, for example, Skelefteå municipality in Sweden and Mo i Rana in Nordland County in Norway, where battery production has already begun.

- How does the City of Vaasa exercise agency toward the battery industry development?

- What are the potential effects of the City of Vaasa's agency on the region's battery development trajectory?

This paper relies on the qualitative approach to provide insight into the agency of the City of Vaasa toward developing the battery industry and the intended and unintended consequences. Regarding the explication of data, we leveraged the perspective in the agency's theoretical framework to make sense of what actors do to advance the industry. The agency of the City of Vaasa identified in this study includes place-based leadership, for example, creating collaborative space for different actors, for example, through the GigaVaasa, and mobilizing resources for infrastructural development to support investors and talent attraction. Next is Institutional entrepreneurship, for example, the issuance of operating licenses to investors, and innovative entrepreneurship, for example, investment in infrastructural development. We continue this article in the following order and section numbers: theoretical framework (s.2), methodology (s.3), findings (s.4), discussion (s.5), and conclusions (s.6).

2 AGENCY IN GREEN PATH DEVELOPMENT

GPD requires the indispensable actions of actors for activating other assets that on their own cannot restructure a region; examples of assets that are transformed via agency include infrastructural and material assets (e.g., machines, physical infrastructure); industrial assets (e.g., technology, financial resources); natural assets (e.g., land); institutional assets (e.g., former and informal regulations and regulations); and human assets (e.g., knowledge, skills, and competence) (Firlus et al., 2023 p. 271; Trippl et al., 2018; Trippl et al., 2020). Agency is therefore imperative for setting the direction and prospects based on future societal expectations (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998), and this involves “imagining new initiatives for the future” (Garud et al., 2010, p. 770) and finding solutions (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Sotarauta et al., 2021). Decarbonization represents a shared future within Europe; one way of actualizing this is through regional restructuring, for example, by modifying or diversifying existing assets or creating new industries (Grillitsch & Asheim, 2018; Martin & Sunley, 2006). In GPD literature, actors' agency is categorized based on the degree of their access to power, resources, and influence. The first set is the trinity agency, comprised of place-based leadership, Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship, and institutional entrepreneurship (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019). The second set is the structural maintenance agency; the actors within this category play a marginal role in GPD due to their limited access to power and resources (Jolly et al., 2020). Sometimes, an actor or group of actors can exercise multiple forms of agency that could be similar, independent, sometimes overlapping and aligning (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Jolly et al., 2020; Miörner, 2020; Sotarauta et al., 2021; Trippl et al., 2020).

2.1 Place-based leadership

GPD requires collaboration, governance, and planning (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Sovacool et al., 2020). Place-based leadership is thus exercised by different actors, for example, “individuals, and groups of individuals, who tend to possess a greater range and depth of assets—including a commitment to advancing the region—than other actors” (Sotarauta & Beer, 2017 p. 212). The typical place-based agency includes raising attention to strategic areas of concern, mobilizing other actors for collaboration (Sotarauta et al., 2021), planning (Gibney et al., 2009; Sotarauta, 2016), creating favorable conditions and opportunities to enhance new developments, and supporting entrepreneurs by organizing the necessary resources to enable such transformation (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Jolly et al., 2020). It is argued that the degree to which actors in different regions can create a conducive operating environment for entrepreneurs accounts for why some regions are more successful than others (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019). From the policy landscape, place-based leadership is vital for actively influencing policy decision-making (Dawley et al., 2015) through discussions that shape a region's economic future (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019) especially as regions are increasingly adopting GPD as a way of reshaping their future. That being the case, these actors coordinate the development process (Sotarauta et al., 2021; Sotarauta et al., 2022) by fostering “localized interactions and learning to support the emergence of collective expectations and perceptions of future development opportunities” (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019, p. 714). These interactions shape and promote the narratives and discourse on regional aspirations, expectations, and goals (Jolly et al., 2020). For example, as empirical studies reveal, regional and municipal authorities play a central role in transforming the pulp industry into an eco-friendly sector (Sotarauta et al., 2022).

2.2 Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship

These groups of actors are concerned with “breaking with existing paths and working toward the establishment of new ones” (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019, p. 710). Put differently, they are concerned with “acting on perceived opportunities by combining different knowledge bases, often from distinct institutional fields and creating new value-added activities” (Jolly et al., 2020, p. 178). They usually comprise private investors, startups, and entrepreneurs who identify investment opportunities for developing new paths or strengthening existing ones and risk their resources (finance and technology) to create value with the hope of positive returns (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019). Within the battery context, for example, in the Vaasa region, firms have expressed interest in investing in the industry (Gigavaasa, 2021; Niemi, 2023; VASEK, 2023). Likewise, in the Skelefteå municipality, Sweden, and Mo i Rana, Norway, private investors, for example, Northvolth and Freyr, have already begun battery manufacturing (Freyr, 2024a; Northvolt, 2024). The former has over 3500 people working for the company, while the latter is already implementing some strategies in its human capital development, for example, (70%) on-the-job learning, with 20% learning based on interaction with others (Freyr, 2024b). Indeed, different factors can influence innovative entrepreneurship, such as the contextual conditions where they operate, for example, regional industrial composition, the prevailing circumstances (cf. Boschma et al., 2017; Grillitsch & Asheim, 2018; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019), the learning opportunities, and the presence of strong institutions that foster entrepreneurship (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019).

2.3 Institutional entrepreneurship

GPD is complex and dynamic, requiring actions that respond to these changes; this means that agency is not static (Sotarauta et al., 2022). Hence, institutional entrepreneurs are seen as “individuals or groups of individuals but also organizations or groups of organizations that originate change processes contributing to the creation of new institutions and/or transformation of existing ones” (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019, p. 711). They ensure that regions pursue policies that lead to regional growth and sanction activities they consider inimical to the region (Soskice, 1999). In other words, the institutional agency can enable and constrain the structure or environment for GPD (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Mazzucato, 2015). The exercise of innovative agency may require enacting new rules, modifying an existing one, or ensuring compliance with regulations (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Sotarauta et al., 2021). The agency of institutional entrepreneurs is aimed at influencing institutional arrangements when necessary because creating new opportunities requires modifying rules and regulations (Jolly et al., 2020). Empirical studies, as highlighted earlier, show how regional authority exercised its institutional agency in different sectors to advance GPD (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Jolly et al., 2020; Miörner, 2020; Sotarauta et al., 2022).

2.4 Structural maintenance agency

The agency herein is exercised by actors with limited access to power and resources compared to the Trinity agents. Consequently, they play marginal, minor, or oversight functions in ensuring the Trinity performs its duties accordingly (Jolly et al., 2020; Sotarauta et al., 2021). For example, fringe actors such as “civil society organizations, ordinary citizens, user associations, environmental movement” (Jolly et al., 2020, p. 180) exercise agency often through criticism, pressurizing, and sometimes resisting the actions of the Trinity (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019; Jolly et al., 2020). The second set of actors play facilitating roles that enhance the actions of the Trinity, for example, the “universities, educational facilities, business development organizations, industry organizations, cluster organizations, science parks, and incubators” (Jolly et al., 2020, p. 178).

To contribute new empirical insight on GPD in line with Asheim et al. (2016) and Uyarra et al. (2017), we use the agency framework to help organize our findings; in addition, we developed the agency synchronization and cyclicality model to deepen the understanding on how the agency is exercised, and the interplay of effects which leads to a continuum of actions and outcomes. The model can be leveraged in future studies as an analytical tool for understanding agency toward developing new green industries in other contexts. We elaborate on the model in subsequent sections.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research strategy and methods

Our study is based on a single case study approach (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2013) of the City of Vaasa agency to the battery industry development. We utilized content analysis for the secondary data, for example, official reports, public information on the websites of regional actors, and scientific articles. These documents provided insight into the Nordic battery context and GPD. The content analysis is based on the READ technique (readying, extraction, analyzing, and distilling) (Dalglish et al., 2020, p. 1424). We searched the topics on GPD; we perused the abstracts and read the entire literature in search of the following in the document: the research aim, focus sector, empirical background or cases, and methodological approach. We identified, extracted, and jotted down relevant points in studies on actors' agency in GPD; afterward, we analyzed the critical points of the studies and distilled the results, which reveals how actors' agency is exercised within the emerging battery industry.

We leveraged the non-probability sampling technique (Rahman, 2023) based on convenience in selecting the actors that were available at the time of data collection; our final decision on the actors to interview was purposively reached to ensure the inclusion of heterogeneous actors that we considered relevant to our study. We gathered the communicated positions of 10 actors through a semi-structured interview (cf. Ruslin et al., 2022) as it aligns with our interest in finding out their perspective on how the City of Vaasa exercises its agency toward the battery industry development and the consequences of such agency to the region's energy transition and development trajectory. To accomplish this, we purposively selected 10 multilevel actors (stakeholders) operating at the cooperate level (academia, energy companies, development agencies) and the individual levels, respectively, because “they are most likely to yield appropriate and useful information” (Kelly et al., 2010, p. 317). The respondents are categorized based on Jolly et al. (2020), as shown in Table 1. They include institutional and place-based leaders, for example, the Vaasa Chamber of Commerce. Innovative agents, for example, Danfoss, Environmental Engineer, Entrepreneur, and Vaasan Sähkö. Facilitating agents, for example, Hanken School of Economics, Merinova, Viexpo, and Dynamo. Lastly is the Fringe agent, for example, the retail worker. Although respondents' communicated positions are from individual actor perspectives, we ascribed their orientation to the organizations they are affiliated with as this could, perhaps, represent a mainstream view on the agency of the City of Vaasa. During the interview, we observed that while some agents were more critical of the agency of the City of Vaasa in the battery industry development process, the opposite was the case for other agents, probably due to their level of interest and involvement.

| Respondents | Profile | Agent | Orientation toward the agency of the City of Vaasa |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Environmental Engineer, City of Vaasa | Innovative agent | Less critical (because they serve the interest of the City of Vaasa in fostering regional energy transition). |

| R2 | Citizen (retail worker) | Fringe agent | Less critical (due to the level of information and knowledge on the City of Vaasa's initiative). |

| R3 | Vaasan Sähkö | Innovative agent | Less critical (they are incumbent firms interested in energy transition). |

| R4 | VIEXPO | Facilitating agent | Less critical (they facilitate regional energy transition). |

| R5 | Hanken Business School | Facilitating agent | Very critical (they are neutrally involved in the industry development process). |

| R6 | Merinova | Facilitating agent | They are very optimistic (they are driving the transition agenda as one of the main actors). |

| R7 | Entrepreneur | Innovative agent | Less critical (they are searching for entrepreneurial opportunities in the regional energy transition process). |

| R8 | Danfoss | Innovative agent | Less critical (they are incumbent firms interested in energy transition). |

| R9 | Vaasa Chamber of Commerce | Place-based/institutional agent | Less critical (they facilitate regional energy transition). |

| R10 | Dynamo (local development organization) | Facilitating agent | Less critical (they facilitate regional energy transition). |

The individual identities of the respondents are identified using the codes R1 to R10 to ensure their anonymity. A standardized question (Hopf, 2004) was administered to the respondents via the technology-mediated platform Zoom, and their responses were recorded with their consent (Klykken, 2022). The next step was to transcribe the recording using the digital tool Transkriptor to convert the Zoom recorded interviews to text, thereby enhancing the validity of our data, that is, the correctness and accuracy of the responses from the interview (Mohamad et al., 2015). It also serves as a moderator that reduces oversight and bias that could arise in manually transcribed data.

The analysis of the interview data is based on the deductive or hermeneutic approach that allows us to form the coding agenda leveraging an existing theoretical framework (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Kibiswa, 2019). In our case, the themes within the agency theory in GPD guided our analysis. We utilized ocular scanning or eyeballing, which involves thorough scrutiny and familiarization with the data (cf. Bernard, 1981). Also, the interocular percussion test was used to identify the pattern in the data and their alignment with the theory (ibid, p. 406). In line with Mohamad et al. (2015), we ensured reliability in the study using, for example, Table 1, which shows that our respondents are drawn from heterogeneous actors to ensure the study's nuance.

3.2 Research context

Regions have different options and utilize various strategies to advance green paths (Grillitsch & Hansen, 2019). Therefore, as previously stated, to gain deeper insight into actors' agency in an empirically underexplored sector in GPD literature, we choose the Vaasa region (Ostrobothnia) in Finland because the development of the Gigafactory is still in the planning and early development phase. In contrast, other neighboring areas depicted in blue in Figure 1, for example, Skelefteå municipality in Sweden and Mo i Rana in Nordland County in Norway, have already begun battery manufacturing driven by two prominent investors, for example, Northvolth and Freyr.

Indeed, developing the Gigafactory is an intentional and well-thought-out initiative that allows the region to leverage its potential to join the global battery production network. These potentials include the critical mineral deposits in the region, which is a precondition for the industry's emergence (Gigavaasa, 2021), the well-established infrastructure that will enhance access to the production sites (Okonkwo, 2022; Vaasa.fi, 2022), and the renewable energy mix (Aslani et al., 2013; Aslani et al., 2013) for low carbon emission in the production process. Other supportive structures to be leveraged include a cluster of regional educational institutions essential for supporting battery-related education and research and the active institutional collaboration between public and private organizations (cf. Gigavaasa, 2021; Okonkwo et al., 2024). Recent inquiries into the economic prospects of investing in the region have shown positive results (Financial Times, 2023), meaning that the completion of the Giga factory project will further boost the European battery production capacity, which is expected to increase significantly by 2025 (Bridge & Faigen, 2022).

4 FINDINGS

This section presents our findings on how a non-firm actor, the City of Vaasa, exercises agency toward the battery industry's development and its concomitant effects.

4.1 The City of Vaasa exercises place-based leadership for the industry's development

“… the whole GigaVaasa concept or initiative or the whole battery energy storage development is focused around the energy transition toward carbon neutrality and to move away from the dependence of fossil fuels or energy” (R9).

“I do not know; I know too little about this project. Although I read that it is good for the environment, I would like to know more about it” (R2).

“We do not want to talk about certain things, and the media frames things as inevitable in a certain way, so there cannot be any democratic debates; if solutions are inevitable, there must be alternatives to have a good debate so that is the biggest challenge I see on fostering alternative imaginaries” (R5).

“We need more people to move into the region or the city, and this is then one strategic investment of the GigaVaasa to build on the existing know-how and profile that we have here. When or if these investments come true, this automatically means a lot of new job opportunities within the industry” (R9)…“We should consider getting the region as attractive as possible, including jobs” (R10).

“I think the main challenge is to convince the investors that we are going to have the workforce, and this is a problem we share with neighboring cities such as Umeå, Skellefteå, and Jakobstad; we are seeing a drain of young educated people out of the region. We need to solve the question of how we can get educated people to want to come here and stay” (R10).

4.2 The City of Vaasa institutional entrepreneurship mitigates prevailing realities

“We cannot have the situation that these kinds of companies are waiting like months or even years to get the final decision if they are allowed to build this kind of factory in Finland” (R6).

“The political situation, I would say, is the biggest challenge because our eastern neighbor attacked Ukraine, so from the security point of view, I think it is the biggest challenge” (R3).

4.3 The City of Vaasa innovative entrepreneurship boosts infrastructure development

“Many people do not really understand the magnitude of this initiative or the possibilities and challenges that lie ahead, I see mostly positive problems” (R4).

Existing infrastructure is being renovated, while there is investment in social amenities such as roads, sewage lines, and water pipelines to support the new industrial area and residential environment. Improving these infrastructures will increase the ease of mobility of talent living in neighboring cities who need to commute to work. For example, the region of Umeå and Vaasa cooperates in developing and operating the Kvarken Ports, which receive about 650 ships annually; in addition, the Wasaline's new RO-PAX vessel Aurora Botnia ship that uses battery power, liquefied natural gas (LNG) and biogas was recently launched to improve connectivity between both regions and other areas in Europe for example Lübeck, Antwerp, Zeebrugge and Tilbury (Vaasa.fi, 2024a).

4.4 The potential effects of the City of Vaasa agency

“…the industry will create different needs for everything in principle; there will be more people, of course, meaning more bus transportation, the battery chemical factories will need more construction workers, trucks, and parking spaces” (R6).

“There can be many unexpected things and concerns, such as how the industry will affect the environment, which is a treasured asset in the country; the positive thing is that everybody wants to solve this problem. I think after this year, we are quite much wiser” (R6).

“We never talk about where the material comes from, what problems, conflicts, and political contestations are produced in other places where the material comes from. I see two issues that need to be debated that may not be at the frontline of the discussions, and this relates to the economic growth model and extractivism, which makes energy transition not inherently sustainable. The model raises the first question of whether we can continue to grow no matter what kind of energy sources we have. The second question is if we could organize society differently that does not follow the growth model that looks at the ecological processes more and align our lives with the web of life that we are part of ourselves” (R5).

5 DISCUSSION

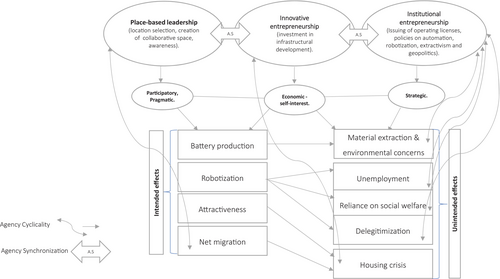

We explicate how the City of Vaasa exercises agency toward developing the battery industry and the effects in the region. By so doing, we increase the underemphasized empirical insight on the role of non-firm actors in GPD, which has been earlier advocated (Dawley, 2014; Dawley et al., 2015; Tanner, 2014; Trippl et al., 2020). We develop a conceptual model in Figure 2 to highlight our findings on the agency of the City of Vaasa, as well as the effect and the interplay of the outcomes from the agency.

The City of Vaasa provides place-based leadership that encourages a participatory GPD process. It does so through the GigaVaasa initiative as a platform for cooperation between the TH actors, for example, companies, regional development agencies, and educational institutions. The City of Vaasa leverages the GigaVaasa to facilitate the involvement of actors in a space (EnergyWeek) where public, private, and other societal stakeholders converge to exchange ideas and knowledge toward advancing the industry. The place-based leadership of the City of Vaasa via the GigaVaasa reinforces the importance of increased involvement of different actors with different beliefs, interests, and opinions (Geels et al., 2017). Indeed, energy transition involves the politics of interest (Bridge & Faigen, 2022) and political struggles among actors (Geels et al., 2017) to optimize their economic interests (cf. Pacheco et al., 2010). In line with our findings, critical discussion on a particular aspect of the industry is not entirely given attention, for example, the environmental effect of extracting the raw materials for the industry. Broadening discussion by creating a critical space for deliberation is imperative as it will cover the interest of more actors and exert some influences, for example, toward ensuring changes in individual and corporate energy behaviors and discourses (Geels et al., 2017). Hence, to deepen the participatory approach, the City of Vaasa could consider creating more social spaces beyond the EnergyWeek devoted to more critical and unpopular debates on the pros and cons of the industry.

Furthermore, the place-based leadership of the City of Vaasa is pragmatic in enabling the region to optimize economic opportunities in the global battery market, leveraging its local resources. The GigaVaasa initiative serves as a platform that facilitates the City of Vaasa's timely response to the high global demands for energy storage. It accomplishes this through its coordination roles, for example, in deciding where private investors will construct their factories to ensure orderliness and a harmonized implementation of the industry's development strategies. In contrast, as studies have shown, a non-pragmatic place-based agency could undermine the timeliness in exercising agency (cf. Boschma et al., 2017; Grillitsch & Asheim, 2018; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019), and a delay in the take-off of the industry could result to the late entrance to the global battery production network and the potential loss of competitive advantage.

Going by Pacheco et al. (2010) conception of institutional entrepreneurship (see also Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019), we think that the City of Vaasa's institutional agency is driven by economic self-interest to optimize its gains from establishing the industry. Our findings reveal a concern to ensure more endogenous ownership of the battery industry because “incoming entrepreneurs may be more profit-maximizing than Indigenous entrepreneurs” (Lawton Smith et al., 2005, p. 4; also see Massey, 1995, p. 220). Consequently, in setting the future directions and goals (Garud et al., 2010), if the City of Vaasa adheres to the concern to maximize its economic gains via more support to local investors, we assume that it will adopt more restrictive rules and regulation for exogenous investors while being more liberal to endogenous local firms. We think restrictive policies could benefit the region only in the post-emerging phase of the industry because future institutional change could facilitate the industry's viability as local firms are more likely to reinvest their profits into the region than foreign-dominated owners, who are more likely to repatriate capital.

On the other hand, if such agency is exercised earlier in the emerging phase, foreign investors are likely to rethink their options, and this, over time, may result in investor apathy that could harm the industry's development. The preceding reinforces the notion that institutional change influences the competitiveness of a region (cf. Cooke & Morgan, 1994; Gertler, 2010; Rodríguez-Pose, 2013). While future concerns on ownership are essential, the short- and medium-term focus should be to strengthen the existing institutions to attract more investment for the take-off of the industry. Our findings reveal that the current arrangement slows down potential investors that have expressed interest in constructing the battery factories, thus reinforcing the claim that “actors are confronted with the intentions of many other agents internal and external to a region” (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019 p. 707; Sotarauta, 2016). Consequently, simplifying the permitting process and reducing the waiting time could accelerate private firm actor investment and incentivize other potential investors to bring their resources to the region.

The City of Vaasa, as an institutional entrepreneur, creates favorable conditions for the industry's development. We consider such roles as strategic considering that the City of Vaasa proactively mobilizes resources that are channeled toward investment in critical infrastructure that increases access to the future production sites, for example, street networks have been completed, which are approximately 2.5 kilometers long at the Laajametsä GigaVaasa battery factory area. The streets, which are over 20 meters wide, will also provide easy access for pedestrians and bicycle paths (Vaasa.fi, 2022). The preceding reinforces that institutional entrepreneurs are “a force molding rules of the game and playing fields for innovative entrepreneurs to surface and succeed” (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019 p. 711).

The answer to the question of the effects of agency-driven GPD is quite apparent; we briefly highlight them and then elaborate on the unintended consequences. On the one hand, the intended agency of the City of Vaasa is aimed at future opportunities, such as developing tangible energy storage solutions, products, and services. These represent technological novelty, an offshoot of the actor's agency (cf. Frenken et al., 2007; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019). The industry will also usher in ancillary benefits such as job creation, infrastructural development, increased domestic economic activities, and market demand based on population influx. For instance, when the anode factory is completed in the Vaasa region, the company will employ over 1200 workers (Varjonen, 2023).

On the other hand, emerging paths also face some uncertainties (unintended consequences), for example, a situation where the “market is not well known, might not even exist for a given product, and the technological feasibility is not established” (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019, p. 711). Some of these uncertainties are true to some extent for the battery industry, for example, the environmental effects of extractivism in the value chain (cf. Eadson & van Veelen, 2023), the geopolitical war between Russia and Ukraine, which may influence investors' confidence in investing in neighboring countries such as Finland, and the possible impact of robotization on employment (cf. Teivainen, 2018). The extent to which to navigate these challenges in making the industry competitive is mainly contingent on institutional response. For example, the City of Vaasa can mitigate the challenges of robotization by enacting policies that ensure a balance between the deployment of robots and the use of human labor to complement the production process. Such action will prevent massive unemployment that could exacerbate emigration from the region as young talents tend to move to new locations when they perceive limited opportunities where they reside (Gherhes et al., 2020). Therefore, navigating the adoption of robots while mitigating talent challenges represents an uncertainty that could impede the industry's progress and the chances of optimizing production potential. Indeed, the City of Vaasa is not the only non-firm actor driving the industry's development; we think facilitating actors, for example, educational institutions, must proactively update their curriculum to reflect the competence needs of the industry because individual skills represent a rigid path-dependent factor that takes time and assiduous efforts to change (cf. Grillitsch & Sotarauta, 2019). Taken together, as the preceding has shown, creating a new green path is complex and dynamic with inherent opportunities and challenges; this means that the City of Vaasa must leverage its experiences as a learning curve to improve its agency.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Our study extends the understanding of non-firm actors' agency, which is gradually receiving attention but still largely underemphasized in GPD literature (Dawley, 2014; Dawley et al., 2015; Tanner, 2014; Trippl et al., 2020). We contribute empirical understanding by examining the City of Vaasa agency in developing the battery industry. Since well-established industries have been the focus of empirical investigation, the authors consciously shifted attention to an emerging green (battery) industry whose role in accelerating decarbonization is increasing. To provide new empirical data, the authors leveraged semi-structured interviews with local actors to ascertain how the City of Vaasa exercises its agency and its potential effect. Our findings, as summarized in Figure 2, on the one hand, reveal that the City of Vaasa exercises the Trinity agency (place-based leadership, institutional entrepreneurship, and Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship), for example, in coordinating and mobilizing resources, investing in infrastructure to support the industry and enacting policies to guide the development process. On the other hand, we found positive consequences as an offshoot of the agency, for example, job creation, net migration, and increased revenue from taxable income. At the same time, environmental degradation from mining remains the main downside.

6.1 Conceptual contribution

Our model provides insight into how non-firm actors exercise agency within an emerging green path and the effect. In addition, the model enables us to explain how agency interacts in the industry's development process. First, our model reinforces the claims that an actor can exercise multiple agency (Sotarauta et al., 2021). We extend this notion through the agency synchronization concept depicted with the double-edged arrow (labeled A.S) that flows sideways, for example, the arrow suggests that non-firm actors, through its local initiative, can simultaneously exercise the trinity agency as with the City of Vaasa. We consider the City of Vaasa agency strategic, pragmatic, participatory, and based on economic-self-interest. Second, we introduced the agency cyclicality concept, which suggests that actors' action in GPD is a continuous process, thus reinforcing the notion that agency should not be seen as static (Sotarauta et al., 2022). Agency cyclicality leads to the interplay and continuous circle of outcomes, consequences, and further actions. For example, the intended consequences of actors' agency may lead to unintended results and vice versa. In our case, we assume that more battery production means more extractive activities with the possible environmental impact on groundwater (cf. Beales et al., 2021). As a result, this will necessitate the further exercise of institutional agency through new rules and regulations as a preventive and mitigative governance measure. Likewise, as battery manufacturing begins, there will be a need for more human (labor) and technological resources (robots); consequently, new regulations to equilibrate and optimize their utilization will be needed. Relying mainly on human labor could impact the commercial scale or output of the industry; in contrast, disproportionate use of robots could result in massive unemployment with concomitant socio-economic and political consequences, for example, high reliance on social welfare, opposition, and delegitimization of the industry among the populace. Similarly, an improved region's attractiveness via branding would increase net migration, thus necessitating more institutional entrepreneurship in infrastructural investments and the creation of more networks or platforms for knowledge exchange. Our model serves as an analytical guide and a template for comparative studies, especially in ascertaining the roles and effects of non-firm actors' agency in different contexts and the interplay of potential outcomes and consequences.

6.2 Implication of research for policy

While many policy implications can be deduced from our study, we identify addressing the issues of robotization as one strategic area policymakers may consider expediting action because an asymmetric employment situation orchestrated by robotization will create new social challenges that may erode the decarbonization objectives. Similarly, the impact of energy transition (Coenen et al., 2021) is a salient challenge rarely given attention, for example, the environmental impact from the exogenous supply value chain. Policymakers must talk about this more and create a space for open discussion on the downside of transition because, by so doing, the possibility of an increased innovative solution from societal stakeholders can be achieved. Beyond the Nordic context, as many regions increasingly embark on developing the battery industry to support the decarbonization agenda, our case could serve as a reference for stakeholders involved in the industry's development process. Firstly, through our case, they will be more in tune with how local initiatives for similar projects unfold in the Nordic context. The insight from our study could serve as a tool for introspection for non-firm actors, for example, for comparatively assessing their agency in the industry development trajectory. Indeed, contexts differ, so actors' roles will likely not manifest precisely the same way. However, there are bound to be areas of similarities and divergence in which our study could provide new learnings for actors.

6.3 Limitations and future research possibilities

The Vaasa region has other non-firm actors facilitating the industry's development process, for example, educational institutions. Our study only examined one such non-firm actor, that is, the City of Vaasa, representing a purposive and convenient sampling technique for the authors. In our view, investigating the agency of the City of Vaasa should be only a starting point for understanding the roles of non-firm actors within the region as there are numerous other actors, as stated, whose agencies are not covered herein due to the scope of our study. The industry is still in the early planning stages, and this, according to Grillitsch and Sotarauta (2019), is the best time to investigate agency. Therefore, future studies could engage more non-firm actors for nuanced insight. Lastly, since agency in GPD is not static, we think future studies could also re-engage the actors in this study and others, for example, to ascertain their perspectives on the dynamics in the agency of the City of Vaasa and the concomitant effects.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.