Banning protests at oil and gas sites: The influence of policy entrepreneurs and political pressure

Abstract

Direct action by citizens has played a pivotal role in shaping environmental policies in the United States. However, several states have recently enacted legislation prohibiting protests at oil and gas project sites, thus undermining the historical legacy of free speech, the American environmental movement, and environmental justice. This study aims to elucidate the determinants influencing the adoption of bills that prohibit civic protests at oil and gas project sites. Existing policy adoption studies have paid limited attention to the impact of policy entrepreneurs and corporate lobbying on policy adoption. This study contributes to the public policy literature by examining the role of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and corporate political activities, and how their influence combines with other types of political pressure to influence the adoption of bills that outlaw protests at oil and gas sites (anti-protest bills) at the state level. Using event history analysis with Cox regression, we modeled the likelihood of adoption of anti-protest bills across 50 states from 2017 to 2021. Furthermore, to zoom in on a strategy employed by ALEC, we compared the similarity scores between the texts of ALEC model legislation and proposed anti-protest bills. This study found that the adoption of anti-protest bills is explained by the presence of ALEC-tied legislators, the composition of legislatures, gas production, and the oil and gas industry's contribution to the state economy. The influence of ALEC's model legislation in policy adoption, however, is not significant.

1 INTRODUCTION

The United Nations invests substantial resources to persuade global leaders to urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions, yet major emitters like the U.S. persist in endorsing and subsidizing oil and gas expansion. Conventional energy sources, constituting 60% of U.S. energy (EPA, n.d.), remain pivotal to the economy. At the state level, to further support oil and gas development, Oklahoma criminalized citizen protests at oil and gas project sites in 2017, and other states have followed suit introducing similar bills that outlaw citizen protests (“anti-protest bills”). As of 2021, citizen protests at oil and gas project sites are illegal in 16 states. These laws violate environmental justice principles, hindering citizens' voices and potentially harming underrepresented communities.

Why do states increasingly adopt bills criminalizing protests against oil and gas? This article explores factors in states' political and economic environments, examining policy diffusion, innovation, and the influence of groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). American Legislative Exchange Council, a policy entrepreneur, promotes pro-business policies, hosting events for stakeholders, and sharing agendas through exclusive meetings. The role of the oil and gas industry in shaping anti-protest bills is similarly explored, highlighting its understudied impact on environmental policymaking. The article also delves into ALEC's strategies, including model legislation. Inspired by Oklahoma's 2017 anti-protest bills, ALEC created the “Critical Infrastructure Protection Act,” facilitating the introduction and adoption of similar laws criminalizing protests at oil and gas sites.

This study makes significant contributions to the existing literature on environmental and energy policy in several key ways. First, it investigates the drivers behind anti-protest bills, an area that has received limited research attention to date. Given the historical significance of social movements in shaping U.S. environmentalism and policy, understanding the factors influencing the emergence of anti-protest bills is essential for comprehending the potential obstacles within American environmentalism—a realm traditionally characterized by citizen-centric and grassroots-driven efforts. Second, much of the focus in environmental and energy policy research revolves around the promotion of “pro-environmental” measures such as renewable energy policies and climate change mitigation. By analyzing policies that diverge from global shifts toward cleaner energy, this research contributes to a well-rounded perspective on the energy policy landscape. Third, the study delves into the roles played by organizations like ALEC and corporate lobbyists in the policy adoption process. American Legislative Exchange Council's history of advocating for pro-development agendas and the substantial financial and political resources possessed by the oil and gas industry underscore the potential influence of vested interests. Building on the literature on political party affiliation and ideology as predictors of policy adoption, this study scrutinizes the impact of entrepreneurial and political pressures. Additionally, the study assesses the efficacy of entrepreneurial strategies, further enriching the understanding of policy adoption dynamics.

To explore the factors driving state adoptions of anti-protest bills, we collected data about anti-protest bills across 50 states from 2017 to 2021, and used event history analysis with Cox regression to examine ALEC's and the oil and gas industry's roles in the spread of these bills. We also used a text similarity score generated by a plagiarism detection software to estimate the effect of the model bill on the likelihood of policy adoption.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

The theoretical foundation for this study is drawn from the following concepts: diffusion of innovation, policy entrepreneurs, and corporate political activities. We build on the limited literature that incorporates policy entrepreneurs and corporate political activities into studies of policy diffusion by exploring factors related to anti-protest bill adoption, and by examining interactions between different types of political pressure and state contextual factors. Further, we explore the specific strategies by policy entrepreneurs.

2.1 Diffusion of innovation theory

Diffusion of innovation theory explains the factors associated with policy adoption and diffusion across jurisdictions, such as U.S. states (Berry & Berry, 1990; Gray, 1973; Walker, 1969). It includes three levels of determinants: internal, horizontal, and vertical. Internal determinants of policy adoption refer to factors within a jurisdiction that influence its decision to adopt a policy (Berry & Berry, 1990; Berry & Berry, 2007), such socioeconomic, political, and other jurisdiction-specific contexts. Horizontal diffusion assumes that a state is likely to consider the experiences of other states and draw insights from those that have effectively addressed a particular issue (Balla, 2001; Walker, 1969). Horizontal diffusion mechanisms include learning or emulation, and competition (Berry et al., 2003; Berry & Baybeck, 2005; Boehmke, 2009; Boehmke & Witmer, 2004; Shipan & Volden, 2008). Relevant to ALEC's influence, communication networks among state government officials may facilitate learning across states (Berry & Berry, 2007). Vertical influence or diffusion refers to the potential for higher levels of government to serve as policy pioneers for lower levels of governments (Berry & Berry, 2007; Daley & Garand, 2005; Karch, 2010). That is, the federal government exerts influence on state governments, encouraging them to align their policies with national goals and priorities. This pressure can take the form of financial incentives or legal mandates (Berry & Berry, 2007; Shipan & Volden, 2006; Welch & Thompson, 1980).

While numerous studies to date have used diffusion of innovation theory to understand energy policy adoption, these studies have primarily focused on renewable energy (e.g., Carley & Miller, 2012; Yi & Feiock, 2012). In parallel, a growing body of literature examines the politics surrounding oil and gas development. Among other topics, these studies focus on public opinion and perceptions (Boudet et al., 2014; Mayer, 2017; Raimi et al., 2020); narratives and framing (Dodge, 2015; Heikkila et al., 2014); coalition dynamics (Betsill & Stevis, 2015; Weible et al., 2016); and conflict (Dodge & Lee, 2017; Heikkila & Weible, 2017; Kagan et al., 2023). However, there is a paucity of studies in the diffusion literature on oil and gas policy. Thus, among this study's contributions is its effort to explore the diffusion of oil and gas related policies using a unique set of determinants. In the following section, we specifically focus on policy entrepreneurs and their entrepreneurial strategies, which, despite their importance in policy adoption, have received limited attention in previous studies.

2.2 Policy entrepreneurs and policy adoption

While studies of policy diffusion often include policy decisions by geographic or ideological neighbors, a less studied but important driver of energy policy adoption is the influence of policy entrepreneurs and their strategies to promote policy change. The roles of policy entrepreneurs merit particular attention in oil and gas development legislation due to the unique divisions between oil and gas companies and other interest groups. That is, ALEC and oil and gas companies are capable of actively promoting their policy agendas using their ample political and economic resources, which distinguish them from opponents who often include grassroots neighborhood and community groups (Dodge, 2015). Furthermore, similar to the limitations of diffusion of innovation studies, existing literature on policy entrepreneurs in the environmental space often focuses on pro-climate agendas, such as through research on climate governance entrepreneurship (Boasson & Huitema, 2017; Mintrom & Luetjens, 2017).

The concept of policy entrepreneurs originated with Kingdon's (1984) work on what is now termed the multiple streams framework (MSF). Kingdon described policy entrepreneurs as innovative individuals willing to invest resources to promote policy change. As part of the MSF, Kingdon described three streams—problem, policy, and politics—that run relatively independent of each other. Policy entrepreneurs use their resources to couple the streams, thus creating a window of opportunity for policy change, or to take advantage of policy windows that have opened (Kingdon, 1984; Zahariadis, 2014). While policy entrepreneurs can come from across sectors and work either within or outside of government (Kingdon, 1984; Petridou & Mintrom, 2021), they share a variety of skills and attributes that they use to promote policy change, such as social acuity and the ability to define problems, build teams, and lead by example (Mintrom & Norman, 2009).

Scholarship on policy entrepreneurs has grown considerably since Kingdon's original work, as evidenced by numerous literature reviews on the topic (Faling et al., 2019; Frisch Aviram et al., 2020). Current scholarship describes policy entrepreneurs as individuals or groups who use their resources to advocate for “major” or “dynamic” policy change (Frisch Aviram et al., 2020, p. 614; Mintrom, 1997, p. 739). Policy entrepreneurs are related to, yet distinct from, other types of policy actors, such as interest groups and lobbyists (Frisch Aviram et al., 2020; Kingdon, 1984; Petridou & Mintrom, 2021). Of notable difference is that policy entrepreneurs generally seek transformative policy change that disrupts the status quo (Petridou & Mintrom, 2021). Kingdon (1984) was careful to distinguish between interest groups and policy entrepreneurs, noting that interest groups typically refer to business and professional groups that often engage in blocking legislation (Frisch Aviram et al., 2020).

In addition to the MSF, the policy entrepreneur concept has been integrated into other theories of the policy process, such as punctuated equilibrium theory and narrative policy framework (Frisch Aviram et al., 2020; Mintrom & Norman, 2009; Petridou & Mintrom, 2021). Of particular relevance, here is the role that policy entrepreneurs play in the diffusion of innovation, described above. Not only might policy entrepreneurs facilitate change within a single jurisdiction, but they also often work across multiple jurisdictions to create widescale policy change (Balla, 2001; Meijerink & Huitema, 2010; Mintrom & Luetjens, 2017; Petridou & Mintrom, 2021). Prior studies exploring the role of policy entrepreneurs in diffusion of innovation have been limited to examining whether the presence of policy entrepreneurs facilitates policy consideration or adoption (Mintrom, 1997). Our research builds on existing literature by examining specific strategies—working through member legislators and drafting model bills—used by entrepreneurs.

Indeed, a focus of recent research on policy entrepreneurs relates to the strategies these actors use, although knowledge about the impact of these strategies is limited (Petridou & Mintrom, 2021; Zahariadis, 2014). Frisch Aviram et al. (2020) describe 20 strategies that policy entrepreneurs use across the stages of the policy cycle. Faling et al. (2019) specifically explore the crossboundary strategies that policy entrepreneurs use to expand, shift, or integrate policies across jurisdictional boundaries, and note a number of conditions that facilitate boundary-crossing, along with a number of challenges that may arise as a result of boundary-crossing. For example, a barrier that entrepreneurs may be well suited to address is the risk aversion of decision makers (Mintrom & Norman, 2009). With this in mind, we explore ALEC's use of a model bill to minimize the risks and burdens on policymakers. Indeed, Mintrom and Vergari (1996) previously noted that drafting legislation may be a tool that policy entrepreneurs use, but the use of model bills and their link with outcomes has not been tested empirically.

2.3 Corporate pressure through lobbying

In this study, we also examine the impact of oil and gas lobbyists. Social movements, including environmental movements affect firms' reputations (King, 2008), stock prices (King & Soule, 2007), and financial performances (Vasi & King, 2012) by drawing attention to issues and problems through various forms of activism. As activists pressure legislatures for regulatory change, firms respond by increasing their lobbying efforts to counteract this influence (Hiatt et al., 2015). Although existing studies on corporate political activities primarily focus on PAC contributions, scholars have questioned their validity as an accurate measure of corporate influence, noting that most corporate political efforts are directed toward lobbying and philanthropic activities rather than Political Action Committee (PAC) contributions. (Chen et al., 2015; Milyo et al., 2000). Moreover, the connection between a political party or politician and a firm’s motivation for campaign contributions remains unclear, as it is often not tied to any specific policy or issue (Delmas et al., 2016).

There are numerous definitions of lobbying ranging from all attempts to influence the policy process (Baumgartner & Leech, 1998) to legal definitions exclusive to the legislature and compensation for lobbying (see Mayer, 2008). Here, we use lobbying to refer to attempts aimed at influencing government decisions through written or verbal communications (NCSL, 2021). What sets lobbyists apart from policy entrepreneurs is that the former may be working on their own or others' behalves and may work for positive policy change or to preserve the status quo. Thus, while policy entrepreneurs may (or may not) engage in lobbying, lobbying does not make one a policy entrepreneur. Lobbying organizations establish both formal and informal relationships with legislators, and these connections significantly influence the development of policy agendas (Fagan-Watson et al., 2015). Oil and gas companies play a crucial role as political actors and have emerged as the most influential interest groups in many countries (Green et al., 2022). Among other things, the oil and gas industry lobby is well-known for its substantial financial resources (Cumming, 2020).

With limited exceptions (e.g., Willyard, 2019), the environmental and energy policy literature has focused on investigating the influence of corporate lobbies in opposition to pro-environmental policies, such as climate change agendas, greenhouse gas reductions, and clean energy transitions (e.g., Cheon & Urpelainen, 2013; Green et al., 2022; Gullberg, 2008; Kim et al., 2016; Markussen & Svendsen, 2005). However, an equally important aspect is how corporations actively seek policies that create favorable social, political, and physical contexts for their own businesses.

This study extends existing research on influence in individual states, such as Texas (Willyard, 2019) to encompass all 50 states, providing a comprehensive empirical analysis of the influence wielded by oil and gas lobbyists in shaping environmental and energy policies. By doing so, this study aims to shed light on the nationwide implications of corporate involvement in policymaking within the oil and gas domain.

3 STUDY BACKGROUND

3.1 Oil and gas policy conflicts

The U.S. economy is heavily dependent on the oil and gas industry, yet oil and gas development also poses considerable risks for the health and safety of citizens and the environment. The oil and gas pipeline network in the U.S. consists of more than 2.6 million miles of liquid gas transmission and distribution pipelines (Hampton, 2019). With rapid increases in the use and development of natural gas, almost 5800 significant pipeline incidents took place and 257 people lost their lives between 2003 and 2022 (PHMSA, 2023). These incidents cost over $12 billion in present dollars (PHMSA, 2023). Numerous environmental concerns are also associated with oil and gas development, including air pollution, groundwater contamination, water use, habitat destruction, and nuisance issues, such as light, noise, and dust (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2023). Threats to water supplies and sacred sites often form the basis for protests against pipelines, such as opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline led by the Standing Rock Sioux in 2016 (Kagan, 2020). Despite these issues, the oil and gas industry wields tremendous political power, including by using its money and power to control information and create favorable narratives (Cruger & Finewood, 2014; Matz & Renfrew, 2015).

To oppose the oil and gas industry, citizen and environmental groups use various methods to promote pro-environmental agendas. While historically environmental groups primarily relied on outside tactics, such as protests, rallies, and media work, contemporary groups use a broad repertoire of advocacy tactics, including community organizing, lobbying, and social media (Olofsson, 2022; Perkins, 2022). Particularly due to limited options for citizen engagement (Parkins & Sinclair, 2014), one key tactic employed by these groups is organizing protests designed to attract public and media attention with the purpose of expanding conflicts and raising public awareness (Perkins, 2022; Schattschneider, 1960). Thus, efforts to ban protests could pose significant challenges for oil and gas opponents.

The origins of anti-protest bills can be traced to the controversy surrounding the Keystone XL Pipeline. In 2011, TransCanada, a Canada-based oil and gas development company, applied for permitting for the Keystone XL pipeline project running from Alberta, Canada to Oklahoma and Texas in the U.S. Estimated economic benefits from the project in the US alone included the addition of $775 billion to the U.S. GDP, 600,000 jobs, and a combined $5 billion to the states that pipelines pass through (Parfomak et al., 2013). What followed was a political back and forth, both within and across administrations, ultimately resulting in the company abandoning the project after President Biden denied a key permit (Lindwall, 2022).

However, in the course of the political back and forth, under the Trump Administration in 2019, the Department of Transportation proposed an amendment to pipeline safety standards that would include penalties such as jail time of 20 years and fines for damaging or interrupting existing pipelines or their construction sites, which is akin to ALEC's model bill for critical infrastructure (Nosek, 2020). At the time, the Chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce expressed concern that the bill could be used to suppress peaceful protests (Hampton, 2019). Thus, while the Keystone XL project ultimately did not move forward, part of its legacy was to lay the foundation for quelling future opposition to oil and gas infrastructure.

3.2 State efforts to curb protests

While efforts to pass federal legislation banning protests were not successful, state governments have competitively introduced and adopted their own versions of bills that would penalize or suppress both violent and peaceful protests at oil and gas project sites. In 2017, Oklahoma became the first state to criminalize protests at oil and gas project sites via House Bill 1123. Other states have since followed suit, with penalties for violating the anti-protest laws ranging from fines for helping pipeline protesters to felonies for trespassing (Ruddock, 2019). These bans have been the subject of significant controversy, both domestically and internationally. For example, in 2017, United Nations human rights experts urged legislators in the U.S. to half the spread of anti-protest bills that undermine democracy by criminalizing peaceful assembly, including environmental protests (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2017).

The primary concern regarding anti-protest bills is that they suppress free speech and peaceful protests. Property destruction and trespass are already illegal, and thus the need for these bans is unclear other than to serve as an additional deterrent to those who wish to express their views. Free speech under the First Amendment is essential to protecting and supporting a healthy democracy. Particularly in an arena where there is an imbalance of power and where the oil and gas industry has virtually unlimited resources, individuals' rights to organize and speak out against oil and gas interests are critical. Given that infrastructure is already protected under existing laws, the emergence of anti-protest bills appears to be a classic example of a solution chasing a problem, bolstered by the efforts of policy entrepreneurs and corporate interests.

3.3 ALEC as policy entrepreneurs

Among the key supporters and advocates of anti-protest bills is ALEC. American Legislative Exchange Council is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that provides a venue for conservative corporate leaders, legislators, and citizens to share their policy views and agendas (ALEC, 2016). American Legislative Exchange Council describes itself as “America's largest nonpartisan, voluntary membership organization of state legislators dedicated to the principles of limited government, free market, and federalism” (ALEC, n.d.). Contrary to its claim to be nonpartisan, ALEC receives funding from large business and corporate organizations, conservative interest groups, and major fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell, and policy scholars typically regard and study ALEC as a conservative network or organization (Cooper et al., 2016; Hertel-Fernandez et al., 2016). Since its inception in 1973, ALEC has offered model policy bills, legislator training and taskforce meetings, publications, and media campaigns to promote conservative and pro-business policy agendas (Rabe & Mundo, 2007). The ALEC website features a “model policy library,” which archives more than 900 model policy bills from the last 19 years. These model bills are provided in formats that legislators can easily tailor for their states.

Indeed, conservative legislators regularly use ALEC model legislation to achieve policy change across a range of issue areas, including energy policy (e.g., Brown & Hess, 2016) and other areas that disproportionately affect those whose interests are not well represented in policymaking. For example, existing studies have examined the role of ALEC in the rollback and termination of state-level renewable portfolio standards (Jang & Yi, 2022) and in impeding Medicaid expansion (Hertel-Fernandez et al., 2016).

At the beginning of 2018, ALEC created model legislation called the “Critical Infrastructure Protection Act,” which is also widely known as the Critical Infrastructure Bill. The model legislation was primarily drawn from and inspired by HB 1123 in Oklahoma, and was backed by a coalition of pro-oil and gas development groups. The coalition sent letters to state legislators asking them to support ALEC's efforts to promote the Critical Infrastructure Bill (Nosek, 2020), and large oil and gas companies like Koch Industries, Marathon Petroleum, and Energy Transfer Partners launched a lobbying campaign to criminalize protests (Dlouhy, 2019). Connor Gibson, an investigator with Greenpeace who uncovered major forces behind the anti-protest bills, said that “[o]il refiners … orchestrated this unholy alliance of oil, gas, chemical and electric utilities to crush resistance to polluting industries” (Dlouhy, 2019). The companies claim these are indispensable measures necessary to protect against aggressive strategies and actions employed by activists (Dlouhy, 2019).

Thus, as the United Nations calls for economic and social changes to mitigate climate change and disasters, a wide array of stakeholders are fighting to protect oil and gas development by implementing measures to quell climate protests (Nosek, 2020). Along these lines, we investigate how oil and gas companies and their allies contribute to launching, amplifying, and assisting measures to suppress climate protesters.

4 HYPOTHESES

Drawing on our theoretical foundation and its application to the study context, we propose the following hypotheses. Our study advances research on the impact of policy entrepreneurs and other political pressures by exploring the direct effects of ALEC as a policy entrepreneur, its strategies, and how pressure from ALEC combines with other types of political pressure, including state legislature party composition and the strength of the oil and gas industry. To this end, first, we propose three sub-hypotheses to investigate the influence of different facets of political pressure. Our first hypothesis measures the impact of ALEC on bill adoption via its legislative members.

H1a ALEC hypothesis.The proportion of state legislators who are members of ALEC is positively related to adoption of anti-protest bills.

Next, in the context of energy policymaking in the U.S., political ideology has long been known to be a key driver of division: conservatives tout stability and focus on minimizing government regulation of energy markets, whereas liberals prioritize the environmental impacts of energy development and take pro-environment stances in energy policymaking processes (Clarke & Evensen, 2019). For example, the predominance of liberals in the state legislature has been consistently positively linked with pro-renewable energy policies (Carley & Miller, 2012; Yi & Feiock, 2012). This division also holds among citizens views on oil and gas (Borick & Clarke, 2016; Raimi et al., 2020), with conservatives supporting fracking and shale gas development (Bugden et al., 2017; Howell et al., 2017; Mayer, 2017).

H1b Party composition.The proportion of Democratic state legislators is negatively related to the adoption of anti-protest bills.

In addition to the composition of the state legislature, interest groups exert various types of pressure to influence outcomes. As explained above, key among these types of pressure is lobbying through which interest groups attempt to influence legislators through direct contact with them. As such, we posit that the presence of oil and gas lobbyists is an important factor in the adoption of anti-protest bills.

H1c Corporate pressure.The presence of oil and gas lobbyists is positively related to the adoption of anti-protest bills.

Our second hypothesis focuses on a different set of internal determinants. Expanding beyond the state legislature, we posit that certain state characteristics are key drivers of anti-protest bills. Most notably, states vary in the extent to which they are economically dependent on the oil and gas industry (Davis, 2012). In states where the oil and gas industry serves as a prominent economic driver, there exists a notable alignment between governmental revenue, employment rates, infrastructure development, and public service provisions with the growth trajectory of this industry. This phenomenon is exemplified by the case of Texas. In the fiscal year 2022 alone, Texas witnessed substantial influxes of funding, surpassing $2.1 billion, directed toward both the Permanent University Fund and the Permanent School Fund. Furthermore, the state amassed a significant sum of over $203.4 billion through the collection of state and local taxes, alongside state royalties originating from the oil and gas sector (Texas Oil and Gas Association, n.d.). The consequential impact on employment was also substantial, with the oil and gas industry generating 442,966 jobs directly and contributing to a comprehensive total of 1.4 million jobs, spanning both direct and indirect associations with the industry, during the same fiscal year. As such, the presence and expansion of the oil and gas sector function as catalysts, significantly augmenting the state's economy and fortifying its infrastructure. This phenomenon simultaneously helps proponents of the oil and gas industry better legitimize and support their claims for the industry's sustained growth. We generally expect that states that are more economically dependent on the oil and gas industry are more likely to protect the industry through the adoption of anti-protest bills. We measure this both through Gross State Product (GSP) derived from the oil and gas industry and through the level of oil and gas production in the state.

H2 Economic contribution.The economic contribution of the oil and gas industry is positively related to the adoption of anti-protest bills.

Third, we expect to see some interactions between the relationships outlined above as state contextual factors combine with political pressure variables. That is, pressure from the oil and gas industry and ALEC might be more effective in states that are more dependent on the industry, consistent with literature emphasizing the importance of institutional and contextual factors (Mahoney, 2007). Indeed, existing policy and interest group literature on tactics and strategies suggests that contexts, rather than tactics determine outcomes (Hall & Taplin, 2007, 2010). We expect to see this both in terms of the strength of the oil and gas lobby and also in terms of the presence of ALEC, both of which may be critical to bringing anti-protest bills on to political agendas.

H3a Corporate interaction with GSP.The positive effect of oil and gas lobbyists on the likelihood of anti-protest bill adoption is stronger in states with higher economic dependence on oil and gas.

H3b ALEC interaction with GSP.The positive effect of ALEC member legislators on the likelihood of anti-protest bill adoption is stronger in states with higher economic dependence on oil and gas.

4.1 Data and methods for the estimation of policy adoption likelihood

To test our hypotheses, we collected data from 2017 to 2021. For our dependent variable, we collected state-level fossil fuel anti-protest bill information from the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law (ICNL, 2023), which tracks such legislation. Specifically, we focused on bills that explicitly target protests near oil and gas pipelines or project sites. These bills are often referred to as “fossil fuel anti-protest laws” or “critical infrastructure laws.” While some of these bills include other types of infrastructure as well as oil and gas pipelines, it is widely known that they were introduced and enacted specifically in response to and to quell oil and gas protests (Suh & Tarrow, 2022). We coded “0” for states without anti-protest laws and “1” in the year for those that adopted anti-protest laws. Once it is coded “1”, the state was dropped from the dataset.

For our independent variables, first, as a measure of policy entrepreneurs in anti-protest policymaking, we retrieved ALEC member rosters from SourceWatch (2019) for each state and calculated the ratio of state legislators who are ALEC members to the total number of state legislators. This is expressed as a percent. Next, we collected the partisan composition of state legislatures from the NCSL (2023), and calculated the percentage of Democrats at the state legislatures.1 In an attempt to explore the effect of oil and gas industry lobbying, we collected oil and gas industry lobbyist data from OpenSecrets (2023). We calculated the percentage ratio of conventional energy industry lobbyists to state legislators. To measure the economic contribution of the oil and gas industry in each state, we used two key indicators: the GSP generated by the oil and gas industry and the levels of oil and gas production. GSP from the oil and gas industry was collected from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2023), while data on oil and gas production were obtained from the EIA (2023a, 2023c). As noted above, to account for potential interactions between state context and political variables, we introduced interaction terms for ALEC legislators and oil and gas contributions to GSP, as well as for oil and gas lobbyists and oil and gas contributions to GSP. Socioeconomic conditions such as median household income and population were gathered from the U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Unemployment rate data were collected from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023). Lastly, the effect of neighboring states was calculated as the percentage of border-sharing states that adopted anti-protest bills. All independent variables are time-lagged by 1 year. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

| Variable | N | Mean | Std. dev. | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-protest bill adoption | 225 | 0.071 | 0.258 | 0 | 1 |

| % ALEC legislators | 225 | 17.964 | 12.478 | 0.833 | 60 |

| % Democrats in the state legislature | 225 | 26.783 | 10.858 | 8 | 55.120 |

| % Oil and gas lobbyists to state legislators | 225 | 28.869 | 35.565 | 0 | 194.167 |

| Oil and gas contribution to GSP (million $, chained to 2012 dollars) | 225 | 6650.678 | 25521.570 | 4.500 | 222911.200 |

| Oil production (in Thousand Barrels) | 225 | 47042.610 | 169651.200 | 0 | 1,609,034 |

| Gas production (in Million Cubic Feet) | 225 | 592858.600 | 1,467,785 | 0 | 9,109,174 |

| Median household income ($) | 225 | 64771.830 | 11155.220 | 41,099 | 95,572 |

| Population (logged) | 225 | 15.194 | 1.032 | 13.269 | 17.490 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 225 | 4.600 | 1.671 | 2.100 | 11.700 |

| Neighboring state effect (% adjacent states with anti-protest bills) | 225 | 7.719 | 17.372 | 0 | 100 |

A Cox regression model was employed for the event history analysis of anti-protest bill adoption in 50 states from 2017 to 2021. Cox regression is well-suited for testing continuous predictors or incorporating multiple covariates within a single model (George et al., 2014). For rare events, Cox regression provides less biased estimates compared to logistic regression (Van Der Net et al., 2008), and it demands fewer assumptions about data distribution than parametric survival models (George et al., 2014). Event history analysis with Cox regression is regularly used in diffusion studies, including recent studies about the diffusion of energy policy (Berry et al., 2015; Carley et al., 2017).

4.2 Results of analysis

The first part of our analysis models the adoption of anti-protest bills using the hypotheses and variables described above. We also include a second analysis, below, on the influence of model bills. Table 2 shows the results of event history analysis using a Cox model. The model includes the variables shown in Table 1, along with our two interaction terms.

| (1) | |

|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Coefficients |

| ALEC legislators | .102** |

| (.046) | |

| Democratic legislators | −.105* |

| (.058) | |

| Oil and gas lobbyists | .019 |

| (.030) | |

| GSP from oil and gas | 4.430 × 10−4*** |

| (1.240 × 10−4) | |

| Oil production | −3.180 × 10−6 |

| (4.080 × 10−6) | |

| Gas production | −7.030 × 10−7** |

| (3.540 × 10−7) | |

| ALEC legislators | −6.460 × 10−6 |

| * GSP from oil and gas | (4.460 × 10−6) |

| Oil and gas lobbyists | −4.500 × 10−7 |

| * GSP from oil and gas | (1.190 × 10−6) |

| Median income | −1.940 × 10−4*** |

| (5.110 × 10−5) | |

| Population (logged) | −.101 |

| (.450) | |

| Unemployment | −.928*** |

| (.265) | |

| Neighbor | .006 |

| (.012) | |

| Observations | 225 |

| Log Pseudo likelihood | −44.485 |

| Probability > χ2 | .000 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *** p < .01.

- ** p < .05.

- * p < .1.

Supporting our first two sub-hypotheses, results show that ALEC legislators are positively related to the likelihood of anti-protest bill adoption, while the predominance of Democratic legislators is negatively related to the adoption of anti-protest bills. However, we found that the influence of oil and gas lobbyists is not significantly related to the adoption of anti-protest bills. Thus, while the first hypothesis (H1a) on ALEC as a policy entrepreneur and second hypothesis (H1b) on predominance of Democratic legislators were supported in the analysis, the third hypothesis (H1c) on corporate pressure remains in question.

With regard to hypothesis H2, we find that the effects of oil and gas industry's economic contributions to the states are mixed. The hypothesis finds support in that revenue generation by the oil and gas industry (GSP) is positively associated with anti-protest bill adoption. However, we find surprising results for the relationship with oil and gas production. First, the relationship between oil production and the likelihood of anti-protest bill adoption is not statistically significant. Yet, gas production is negatively related to anti-protest bill adoption, which runs counter to expected effects.

Our third set of hypotheses (H3a and H3b) is also not supported. That is, we found no significant interaction effect between measures of political pressure and state economic dependence on the oil and gas industry. While pressure from ALEC is independently significant, the interaction between ALEC and GSP is not significant. Furthermore, as noted above, the presence of oil and gas lobbyists is not significant, and likewise, their interaction with GSP is also not significant.

Table 2 also includes results for control variables. Median household income is negatively related to anti-protest bill adoption, while population is not a statistically significant driver of anti-protest bill. State unemployment rate is negatively associated with the adoption of anti-protest bill, and geographically adjacent states' anti-protest bill adoption is not a statistically significant driver of anti-protest bill adoption in laggard states.

4.3 Effectiveness of ALEC model legislations on policy adoption

Among the motivations for this research is the fact that other studies have discussed similarities between ALEC's model bill and states' anti-protest bills in their narratives without conducting an actual analysis of these similarities (e.g., Nosek, 2020). Thus, while the preceding section found that ALEC members play a crucial role in the adoption of anti-protest bills, a question remains regarding the specific methods they employ in their entrepreneurial activities. As mentioned earlier, ALEC employs a variety of strategies to exert influence on policymaking processes, one of which is through the creation of model legislation. This aspect warrants particular attention as ALEC provides assistance to legislators in their policymaking responsibilities, which demand substantial time, effort, and expertise in dealing with policy matters.

In an attempt to measure the similarity between the ALEC model bill and actual policy bills introduced, we used a web-based, text similarity comparison program called “Dupli Checker,” which highlights overlapping phrases between two documents and generates similarity scores as percents.2

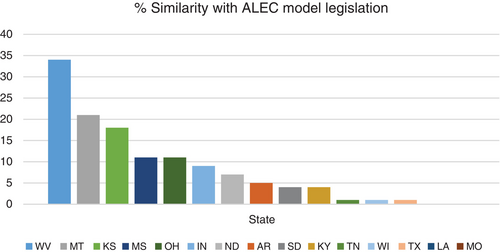

Figure 1 displays the similarity scores to ALEC model legislations for anti-protest bills that were successfully adopted. Among the states analyzed, West Virginia, which introduced and adopted HB 4615 in 2020, showed a relatively high similarity score of 34% with ALEC model legislation. Following behind is Montana's HB 481, with a similarity score of 21%. However, it is noteworthy that other states, such as Louisiana and Missouri exhibit almost no similarity with ALEC model legislations in their anti-protest bills.

To examine further the impact of model bills on policy adoption, we also examine whether there are differences in similarity scores between bills that passed and bills that did not pass. Existing studies on ALEC's model legislations have primarily focused on presenting similarities between ALEC model legislations and state policy bills (Baka et al., 2020; Collingwood et al., 2019; Garrett & Jansa, 2015), but these studies have paid limited attention to assessing the effectiveness of ALEC model legislations as an entrepreneurial strategy in achieving the enactment of bills.

Through our analysis of similarity scores, we sought to identify any discernible differences in the level of resemblance between the defeated and adopted bills as compared with the ALEC model legislations. This analysis allows us to explore whether higher similarity scores to ALEC model legislations are associated with policy adoption. We conducted an independent sample T-test to identify differences in the ALEC model policy bill similarity scores between the introduced bills that were defeated and those that successfully reached the governor's desk. While the average similarity score of bills that successfully navigated the legislative processes is greater by approximately 1.5% points than that of the proposed bills that failed, the difference in similarity scores is not statistically significant. Results are shown in Table 3.

| N | Mean (standard deviation) | F-statistics | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % ALEC model bill copied | Proposed, but not passed | 17 | 9.1765 (7.527) | .204, .1765 | .955 |

| Proposed (passed later) | 14 | 10.6900 (7.7180) | |||

Although the T-test analysis does not confirm our expectation that bills with higher similarity to model legislation are more likely to be adopted, the results in this section show that model bills do play a role in the legislative process, with average similarity scores over 10%, and substantially higher scores in certain states. This analysis does not account for the extent to which elected officials may streamline their efforts by using model legislation as a foundation for state-specific proposals. Thus, while model legislation may help introduce and spread policy ideas, legislators still face similar challenges in achieving enactment as they do with other legislative proposals.

5 DISCUSSION

The literature on the adoption of environmental and energy policies has predominantly centered around clean and pro-environmental initiatives. Scholars in the field have diligently amassed a wealth of findings pertaining to policies designed for climate change mitigation and sustainability. Nonetheless, policies aimed at safeguarding corporate interests and economic development, even at the cost of environmental protection and conservation, have not received commensurate scholarly scrutiny, despite their profound implications for both the environment and society. Building a deeper understanding of these policies and their drivers is particularly important as they gain momentum in today's era of democratic backsliding (Bauer et al., 2021). Anti-protest bills warrant both scholarly and practical consideration, as they threaten the bedrock principles of American environmentalism and stifle civic voices while prioritizing corporate business interests.

By criminalizing civic protests within oil and gas project sites, states find themselves susceptible to accusations of both environmental and democratic regression. This vulnerability is particularly pronounced in an era when developed countries take a proactive role in shaping the agenda and determining the course of action for the transition to clean energy as a vital component of their efforts toward sustainable development and climate change mitigation. Achieving sustainable development and effectively mitigating climate change necessitate comprehensive alterations across economic, social, and environmental domains. However, this bill steers states in a direction where economic development takes precedence over democratic values and the preservation of the environment.

In our endeavor to unravel the driving forces behind the proliferation of anti-protest policies across states, our focus was directed toward understanding the role played by political and industry pressure in suppressing these protests. Since Mintrom's (1997) empirical study of the influence of policy entrepreneurs on policy adoption, the policy adoption literature has still paid limited attention to policy entrepreneurs mainly due to the challenges with collecting relevant large-N data that could be used for the study of policy adoption and diffusion. This study addresses this gap by zooming in on ALEC's influence as a policy entrepreneur and by examining how policy entrepreneur influence interacts with other political and contextual variables.

At an initial level, this study reveals that the presence of ALEC-tied legislators may increase the likelihood of anti-protest policy adoption, which is consistent with other research demonstrating that ALEC effectively promotes conservative policies across the U.S. (e.g., Jang & Yi, 2022). The meaning of this result, however, is also emphasized when read in relation to our other findings. First, existing research suggests that energy and environmental policymaking is largely shaped by partisan politics, and we found that legislative bodies with fewer Democratic legislators are more inclined to support measures aimed at prohibiting protests related to the oil and gas industry. This result reaffirms existing findings on the politics surrounding energy and environmental policymaking (e.g., Carley & Miller, 2012; Yi & Feiock, 2012). Second, in contrast with the role of ALEC and legislative composition, the lobbying efforts undertaken by oil and gas companies do not necessarily correlate with the successful enactment of anti-protest policies. While these businesses are renowned for their substantial financial expenditures and adept use of political influence to shape policymaking in their favor, our analysis revealed a lack of statistical significance associated with the presence of oil and gas lobbyists. The reasons for this finding are not clear, but it is possible that oil and gas companies do not invest resources in unfavorable contexts or wish to avoid the potential repercussions of unfavorable public sentiment (Smith & Richards, 2015), underscoring the delicate balance between pursuing policies that may benefit the industry and mitigating potential negative consequences that could arise from heightened scrutiny and opposition. Future research should continue to explore this relationship.

Third, as expected, we found a positive association between revenue generation from the oil and gas industry and the adoption of anti-protest bills. The extent to which a state is economically dependent on the oil and gas industry holds strong implications for whether each state prioritizes and protects the oil and gas industry (Davis, 2012). However, we did not find support for our hypotheses predicting interactions with this context.

Read together these findings underscore the important role that policy entrepreneurs can play in policy diffusion. Oil and gas interests are generally known to have significant influence in policymaking (Downie, 2017), but their influence may be watered down in unfavorable political contexts. In contrast, our model suggests that powerful organized interests acting as policy entrepreneurs can overcome difficult contexts. Other studies have demonstrated the primacy of political context in policy change and advocacy (e.g., Hall & Taplin, 2007, 2010). However, even controlling for contextual factors, such as the political composition of state legislatures and the extent to which state economies depend on oil and gas interests, we still see that ALEC can be a powerful force in state policymaking, particularly through its member legislators.

Thus, this research suggests that policy entrepreneurs, in addition to other political and interest group variables, should be considered in diffusion studies. While early studies of policy diffusion focused primarily on the influence of neighboring states, along with internal socio-economic and political factors (Berry & Berry, 1990; Walker, 1969), more recent research has expanded these variables to include factors like the type of information that states consider in policy adoption (Grossback et al., 2004), along with the mechanisms of diffusion (Maggetti & Gilardi, 2016). This study builds on recent research by highlighting the powerful role that policy entrepreneurs may play in policy diffusion. While this study focuses on a particular policy and issue area, it raises important questions for future research, such as when and how policy entrepreneurs are successful in overcoming unfavorable contexts and what implications for democracy may result.

In a surprising finding, our analysis uncovered a negative relationship between gas production and policy adoption, but no significant relationship between oil production and policy adoption. There is certainly an overlap between states with high oil and high gas production. For example, in our study period, the top five producers of both oil and gas include Texas, Alaska, and Oklahoma (EIA, 2023b, 2023d). However, the more recent proliferation of extraction using technologies such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has brought oil and gas production into new regions, which may be at least partially reflected in states' gas production. Not only did new technologies significantly increase oil and gas industry presence in states like Pennsylvania and Ohio, but it also brought oil and gas development to new communities in states like Colorado and New Mexico (EIA, 2023b, 2023d). Thus, policy contexts may be less favorable for oil and gas development in states with high gas production where the industry is relatively new, but these findings should be explored in future research.

Finally, our analysis does not support our expectation that bills more similar to model legislation are more likely to be adopted. However, the influence of model bills should be explored in future studies. While we did not see a significant effect in this study, the availability of model bills may increase the likelihood of bills being introduced in the first place or could spark increased opposition from legislators aware of their origins. From a descriptive standpoint, states seem to emulate and draw inspiration from ALEC's model legislations when crafting their policy bill text. Thus, additional research on the use, benefits, and challenges associated with model legislation is needed. Future research might also explore whether the variability in similarity scores can be plausibly explained by the differing characteristics of state legislatures. For example, in states that most closely followed the ALEC model, such as West Virginia, Montana, and Kansas, legislators earn an average salary of approximately $18,449 and dedicate about 57% of a full-time workload to their legislative duties. In contrast, states with the lowest similarity to the ALEC model, such as Louisiana and Missouri, tend to have legislators who are predominantly full-time, with 74% of their time committed to legislative work and an average salary of around $41,110 (Ballotpedia, 2017). Though beyond the scope of this study, these trends might have implications for regulatory capture and the abilities of powerful interests to influence policymaking.

Limitations of this study arise from our reliance on quantitative analysis. First, this approach may not fully illuminate the nuances of how ALEC members and corporate lobbyists engage in legislative activities related to the adoption of anti-protest bills. Second, it is possible that certain events, which could have influenced the adoption or non-adoption of such bills, may have gone unaccounted for in our quantitative analysis. Although event history analysis with Cox regression allows us to demonstrate the significance of variables like ALEC-affiliated legislators in policy diffusion, in-depth case studies of individual states could also provide insights into the specific strategies ALEC member legislators use to promote anti-protest legislation. Additionally, due to data limitations, our models do not account for factors, such as whether particular protests or focusing events directly precipitated policy adoption. Third, while Cox regression is a powerful tool for examining policy diffusion, the rapid spread of anti-protest bills within a short time frame—beginning with Oklahoma's adoption of the first such bill in 2017—presents challenges. As more time passes and additional bills are introduced, a longer timeframe within a longitudinal approach may offer deeper insights into the factors driving the continued proliferation of anti-protest legislation, as well as potential reasons for any slowdown in the wave of bills aimed at restricting protests near oil and gas infrastructure.

6 CONCLUSION

The transition toward cleaner energy sources stands as a pivotal strategy for mitigating climate change, considering that burning fossil fuels is a leading contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (EPA, n.d.). While a global shift toward clean energy is rapidly underway, with numerous nations aligning themselves with the Paris Agreement, the U.S. has shown comparatively less activity, and even dormancy, in its pursuit of climate change mitigation. Over the past few years, the U.S. has tacitly supported oil and gas production, a stance that raises concerns.

The transition to clean energy is complicated by the fact that many states have experienced socioeconomic and political advancement owing to their oil and gas industries. While it is important to recognize the crucial role oil and gas play as essential energy sources underpinning the U.S. economy and industry, efforts to ban protests at oil and gas sites are problematic, particularly as social movements and direct action lie at the heart of American environmentalism.

REFERENCES

- 1 While scholars typically utilize Berry et al. (1998) state government ideology score to measure the government ideology at the state level, the latest data available is for 2016.

- 2 Prior to conducting the similarity analysis, we redacted any irrelevant or non-meaningful texts present in the policy bills, including line numbers, page numbers, and section numbers. This step was taken to ensure that the analysis focused solely on the substantive content of the bills, without being influenced by any structural or organizational elements.