Between science, authority, and responsibility: Exploring institutional logics to rethink climate governance

Abstract

This article explores the logics mobilized by stakeholders involved in national climate governance to identify ways of conciliating them for sound governance. Based on the theoretical framework of institutional logics, the study offers an innovative perspective on climate governance and the management of green funds. Content analysis of the briefs submitted (N = 46) to a public hearing in Quebec (Canada) reveals three competing institutional logics: scientific governance, authority-based governance, and participative governance. The results of this research have significant managerial and political implications for our understanding of the interactions between the different logics and for identifying ways to optimize climate governance. It also addresses essential but under-researched aspects of national climate governance and green fund management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Climate change represents one of the major challenges of the 21st century. Its consequences will potentially devastate humanity and ecosystems worldwide (Lenton et al., 2019; Ripple et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). Governments, businesses, and citizens are increasingly aware of the situation's urgency, and are seeking solutions to mitigate global warming's effects and adapt to its inevitable consequences (Fischer & Knutti, 2020; Mechler et al., 2020). In this context, climate governance has become a central issue for researchers, policymakers, and interested stakeholders (Zelli et al., 2020). However, climate governance faces challenges of coordination and effectiveness across different levels of government and sectors, exacerbated by the polycentric nature of governance where multiple decision-making centers often interact with divergent objectives (Jordan et al., 2018).

This research looks at national-level climate governance, a little-explored but essential area, using institutional logics as an analytical tool to detect the complex interactions between the various actors actively engaged in the fight against climate change (Falkner, 2016; Jordan et al., 2018). In a context marked by a rise in climate skepticism, where political figures and movements such as “Trumpism” openly deny facts about climate change (Dunlap & Brulle, 2020; Oreskes & Conway, 2022), it seems paradoxical that even actors who agree on climate urgency are experiencing difficulties in harmonizing their efforts. The current study focuses on these internal challenges, highlighting how, despite accepting the scientific consensus, divergences in the institutional logics of these actors complicate the coordination of actions.

Indeed, climate governance faces significant structural challenges, including the complexity of coordinating effective action across multiple levels of government and diverse economic and social sectors. This complexity is accentuated by its polycentric nature, where multiple decision-making centers must interact and collaborate despite sometimes divergent objectives and interests (Abbott et al., 2017; Lofthouse & Herzberg, 2023). Navigating this fragmented governmental landscape and reconciling various institutional logics is crucial to implementing policies that tackle climate change and adapt to its effects (Bernstein & Hoffmann, 2018).

This research examines the interactions between the institutional logics of the actors involved in climate governance in Quebec (Canada) to identify ways of reconciling them and thus promoting effective governance. By exploring the motivations, vested interests, and mechanisms by which actors integrate and operate within these governance systems, we aim to understand better the complex dynamics underlying the fight against climate change. Our study focuses on how these different institutional logics—defined as sets of practices, beliefs, and rules that materialize power relations within institutions (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999)—can facilitate or hinder decision-making processes and strategic actions.

By using institutional logics as an analytical tool, we seek to explore these interactions and address several gaps identified in the scientific literature. First, our research addresses the need to study climate governance at the national level (Falkner, 2016; Jordan et al., 2018; Keohane & Victor, 2011) and to explore the challenges of green fund governance (Abbott & Snidal, 2009; Van de Graaf & Colgan, 2016). Moreover, our study also responds to Lounsbury et al.'s (2021) call to examine institutional logics as a complex and evolving phenomenon and to consider their cohesion as a problem for study. By analyzing the logics and prior interests of actors in climate governance systems, our work offers a deeper understanding of the interactions between different institutional logics and their role in climate governance (Aamodt, 2018; Auld et al., 2015). Thus, this study contributes to understanding climate governance dynamics and offers avenues for improving decision-making practices and designing more effective collaborative arrangements.

The remainder of the paper is organized into five parts. The first introduces the literature on climate governance and green fund management. The second presents the conceptual framework of the institutional logics mobilized in this study. Then, the article discusses the method of content analysis and how it was applied to the briefs filed during a public consultation. Finally, after presenting the study results, a discussion highlights the research's scientific, political, and managerial implications.

2 CLIMATE GOVERNANCE AND THE MANAGEMENT OF GREEN FUNDS

As a political and social issue of global significance, climate governance requires decisive coordination at all levels of government and among various sectors to achieve common goals (Aykut & Dahan, 2014; Ciplet & Roberts, 2017). This task is made more challenging by the rise of climate skepticism, a phenomenon that, fueled by populist currents, denies established scientific evidence and deepens divisions, making climate governance even more complex (Dunlap & Brulle, 2020; Oreskes & Conway, 2022). In this paradoxical context, where even actors who agree on the need to act struggle to harmonize their efforts, the importance of green funds as mechanisms for decision-making and action becomes decisive (Antimiani et al., 2017).

In this global sense, governance guides social organizations through collective action to reach shared goals (Bäckstrand et al., 2021; Torfing et al., 2012). This interactive process allows society and its social and economic components to negotiate goals collectively (Ansell & Torfing, 2016). Climate governance focuses on the complex decision-making process associated with climate change (Sapiains et al., 2021). It considers the specifics of adaptation, defined as adjusting to actual or expected climate change and its effects; it is, therefore, generally more locally oriented (Lesnikowski et al., 2021; Termeer et al., 2011; Wellstead & Biesbroek, 2022). These authors pointed out that issues related to climate change mitigation also require human intervention to reduce emissions or enhance greenhouse gas capture. Such intervention requires local initiatives to achieve global goals, and thus requires multi-stakeholder climate governance.

However, climate governance faces issues of balance. Aykut and Dahan (2015) questioned whether climate change is “governable.” For example, climate disasters seem to escape any short-term response, and no decision appears to have reversed the trend of climate disruption (Averchenkova et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2022). The climate issue has been on the global agenda for 50 years (Gupta, 2014; Heinen et al., 2022) and is the subject of recurrent summits involving international leaders (Ciplet & Roberts, 2017). For Baeckelandt and Talpin (2023), local governance alone cannot address global climate externalities. In turn, the national or sub-national government is affected by competing ideologies and interests. Democratic systems follow recurrent electoral cycles, while expected political decisions are subject to very long and often closed processes (von Lüpke et al., 2023).

In the complex dynamic of climate governance, the state has historically appeared as the dominant structure attempting to control national environmental problems (Kythreotis et al., 2023; Ntounis et al., 2023; Tzaninis et al., 2023). However, climate governance must primarily improve government decision-making processes (Dubash, 2021). It is not an alternative to politics but a complementary element. Moreove, climate governance must contribute to democratic legitimacy, requiring—among other things—its reintegration into institutionalized procedures (van der Heijden, 2019).

The importance of climate governance is thus undeniable, especially given global environmental and socioeconomic challenges. A unique mechanism in this area is green funds. These funds play a crucial role in the decision-making and implementation of climate actions, with colossal budgets at their disposal (Antimiani et al., 2017). Despite their importance, the scientific literature has paid them scant attention. Some work has focused on their effectiveness and efficiency by studying them on a global scale (Tang & Chen, 2020), or in individual countries such as the United Kingdom (Moreira, 2016) or South Africa (Mohamed et al., 2014), or through comparison of large markets such as China and the United States (Dong, 2022; Phan, 2020). However, the study of green fund governance remains insufficient, apart from some research on specific mechanisms such as the role of actors in the management of taxation systems (Puaschunder, 2023), interactions between actors in environmental market mechanisms (Wang & Zhi, 2016), or investor involvement in the management of funds (Chung et al., 2012).

Given the significant issues at stake and the considerable sums involved, it is essential to examine the logics at work in these funds and national governments' climate governance. To measure the amounts involved, let us recall that several countries have set up national green funds, such as the Green Bank in the United States, which was managing about USD 4 billion in 2021 (GCG, 2021), and the National Clean Energy Fund in India, which had accumulated nearly USD 3.5 billion by the end of 2020 (Central Electricity Regulatory Commission, 2021). In this regard, Aamodt (2018) has emphasized the importance of adopting institutional logics as an analytical framework to better understand climate governance, illustrated here by the management of green funds as operational and far-reaching mechanisms to address climate change. Managing these green funds itself requires adapted and effective governance (Antimiani et al., 2017). Through a long-term comparative study of the implementation of the Paris Agreement in India and Brazil, Aamodt (2018) argued for using institutional logics to better capture fund management and the implementation of decisions on a national level.

3 CLIMATE GOVERNANCE THROUGH THE LENS OF INSTITUTIONAL LOGICS

Friedland and Alford's (1991, p. 249) define institutional logics as “socially constructed historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs, by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences.” For Thornton and Ocasio (1999, p. 804), a logic is a social construct made up of assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals give meaning to their social reality. On this view, it is then possible to determine which logics attribute to individuals and groups of individuals a set of principles and a common language which allow them to achieve their objectives (Friedland & Alford, 1991). There may be multiple complementary or competing logics, adding to the complexity of problem management. It is the responsibility of the state to integrate these different logics into decision-making mechanisms (Greenwood et al., 2011). Alvesson et al. (2019) added that a plurality of logics can exist within the same institution, as is often the case within governments. Lawrence et al. (2006) also introduced a significant element into their definition of logics: the idea that they reflect broader societal discourses that permeate governance and institutions, to which they provide content and meaning.

The work of Loorbach (2010) provides insight into managing social transitions, particularly those pertaining to the environment, by considering the complexity of the governance of these issues across different levels. Loorbach (2010, p. 169) notes that a logic is an “analytical lens to assess how societal actors deal with complex societal issues at different levels but also to develop and implement strategies to influence these ‘natural’ governance processes.” However, this approach underestimates the importance of the context of multiple institutional logics; that is, the coexistence of several structures of values, beliefs, and objectives. Thus, institutional logics present sources of conflict and fragmentation, often impeding sustainable development (Besharov & Smith, 2014). Institutional logics and how they impact the operational outcomes of governance have significant potential to guide or divert transitions toward sustainability (Abson et al., 2017).

Recently, this issue of the coexistence and entanglement of multiple logics has received attention (Ocasio et al., 2017; Sattler et al., 2023; Toubiana & Zietsma, 2017), with a growing interest in studying how organizations apprehend and manage the tensions and contradictions between logics, seeking to solve a “theoretical puzzle” (Sadeh & Zilber, 2019), as is the case in addressing climate change. The use of the conceptual framework of institutional logics is thus already informing the debate. For example, a study by Boiral et al. (2022) has shown how competing logics can explain positions in favor or opposition to the use of pesticides.

Lounsbury et al. (2021) discussed emerging approaches that focus on the sustainability and coherence of institutional logics, highlighting the possibilities of further exploring the role of governance dynamics. Indeed, the authors argued that the concept of logics, in and of itself, is not only relevant but also that, by studying institutional logics as complex phenomena rather than viewing them as explanatory tools, we will be able to explore governance dynamics in greater depth. In doing so, Lounsbury et al. (2021) provide an analytical framework that makes the governance of logics an essential element of institutional orders alongside values and practices. Here, governance indicates a constellation of logics that understand where different governing agents and their interrelationships come from.

4 METHODOLOGY

4.1 Research context

In Quebec (Canada), unlike other regions such as the United States, where climate skepticism is more prevalent (Dunlap & Brulle, 2020; McCright & Dunlap, 2011), the actors involved in climate governance broadly agree on the reality and urgency of climate change. As Mildenberger et al. (2016) pointed out, Quebec strongly recognizes climate change. A proactive environmental policy at various levels of government supports this. This commitment to heightened sensitivity to climate change in Quebec is partly due to a progressive approach (Long et al., 2021) via educational initiatives and effective awareness campaigns, which fosters more integrated climate governance receptive to environmental challenges (Mildenberger et al., 2016).

The Government of Quebec (Canada) prioritizes the fight against climate change. In 2020, it adopted a target of reducing GHG emissions by 37.5% by 2030 compared to 1990 (Government of Quebec, 2020). This commitment has also resulted in adopting three climate change action plans in 15 years. These plans include measures to mitigate GHG emissions and adapt to climate change. One green fund is the main funding source for these measures. Since 2006, the fund has invested over $6.6 billion CAD in the fight against climate change. From 2021 to 2026, the cost of funding the actions planned in the Green Economy Plan 2030 is estimated at nearly $6.7 billion CAD.

In recent years, however, the use of this budget by public authorities has been criticized. In 2014, the Commissioner for Sustainable Development highlighted significant problems in terms of communication practices and accountability. He criticized specific departments for not regularly monitoring program results and for communicating incomplete and patchy data. Among his recommendations, he proposed that monitoring mechanisms be put in place to continuously evaluate results and that specific, measurable objectives be set for each of the funded programs (Vérificateur général du Québec, 2014). However, almost 5 years after this report was published, the Commissioner has again called attention to persistent problems concerning performance monitoring and measurement. The Commissioner described this situation as deplorable: “Nearly five years after the publication of our initial audit report on the Green Fund, we can only regret this situation, especially since the objectives of the Green Fund are large, considerable sums of money are at stake, and parliamentarians have shown a sustained interest in this sustainable development tool” (Vérificateur général du Québec, 2019, p. 17).

Faced with these persistent criticisms and problems, the Quebec government reviewed governance mechanisms to ensure greater coherence in climate action and optimize the use of resources. A public consultation was conducted in 2020 to gather comments and recommendations on the proposed reform of climate governance, with the main objectives of strengthening the monitoring and performance measurement of funded programs and ensuring transparent communication of results.

4.2 Data collection

The public consultation process resulted in 46 briefs from stakeholders of the environmental, transportation, business, and research sectors and local governments (see Table 1).

| n | |

|---|---|

| Environmental organizations (ENV) | 18 |

| Transportation organizations (TRA) | 3 |

| Local public authorities (AUT) | 4 |

| Business representatives (BUS) | 15 |

| Research organizations (RES) | 6 |

| Total | 46 |

These briefs are written in a format ranging from 5 to 60 pages, for a total of 764 pages to be analyzed. In the briefs, these organizations advocate in detail and with evidence for their opinions about and proposals for improving climate governance. They constitute valuable research material. Indeed, there are briefs that contain evidence-based reflections about shared experiences that were drafted, debated, and validated before being sent to the government.

4.3 Data analysis

To understand the institutional logics that prevail in climate governance, this study uses qualitative content analysis. This research method systematically examines textual documents or recorded data to identify trends, themes, or patterns (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Newman et al., 2023). This approach allows for the interpretation of data based on pre-established or emergent categories and concepts and the formation of relevant conclusions (Krippendorff, 2019).

To understand the institutional logics prevalent in climate governance, this study employed qualitative content analysis, adopting an inductive approach similar to that of Reay and Jones (2016). This method allowed us to dive deep into the textual corpus of the submitted briefs. We also used the QDA Miner qualitative data analysis software to systematically structure and code the data. Following the “pattern-inducing” techniques described by Reay and Jones, we identify recurring motifs that reveal the different institutional logics expressed by the actors involved (Reay & Jones, 2016, p. 443).

Data analysis begins with an initial immersion in the data to capture contextual nuances, followed by identifying text segments that reflect institutional practices and beliefs. We employ an analysis strategy based on emergent patterns (Reay & Jones, 2016, p. 459), grouping textual data into categories that clearly illustrate the institutional logics at play. This process captures the complexities of institutional interactions and offers a comprehensive interpretation of the dynamics underlying climate governance. The categories are verified and refined through an iterative process of comparison and discussion between researchers to ensure consistency and reliability of interpretations. This approach responds to Reay and Jones' (2016, p. 450) call for an analysis that does not simply measure or operationalize logics but seeks to “capture” them through the rich and engaged description. This approach thus makes it possible to paint a faithful portrait of institutional logics as they manifest themselves in the briefs studied.

More specifically, in this study, we used a qualitative and inductive content analysis following the recommendations of Thomas (2006). This approach requires condensing the raw data, relating it to the research purpose by assigning categories of meaning called codes to the data and creating a framework for reference and analysis. The method revealed the cross-referenced meanings of the data set (Barbier & Galatanu, 2000; Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Thus, content analysis allowed us to better understand the opinions, proposals, and institutional logics underlying the briefs submitted during public consultations.

We proceeded by following the five steps Thomas (2006) identified: (1) preparation of the raw data, (2) in-depth reading of the data, (3) the creation of categories or codes, (4) verification of the codes and categories, and (5) the development of an analytical reference framework. This strategy reveals the cross-referenced meanings of the data set (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). It also allows for a better understanding of the opinions, proposals, and institutional logics underlying the submissions made during the public consultations. The coding process identified themes (N = 3, institutional logics), sub-themes (N = 10, dimensions of logics), and codes (N = 71). Appendix 1 presents the coding tree. Saturation in the emergence of new codes or themes was reached after analyzing 26 briefs, ensuring complete coverage of emerging themes and concepts (Hennink et al., 2017).

This study emphasized validation and methodological rigor throughout the analysis and carried out independent double coding (Thomas, 2006). To do this, two researchers worked in parallel by coding the documents separately and then comparing their results. Rather than revealing major disagreements, this process led to complementary readings to enrich the meanings assigned. When researchers assigned codes differently, they discussed their respective understandings and choices, allowing for greater consistency in the analysis. This iterative process of validation, which involved frequent returns from the coding tree to the data and exchanges within the research team, ensured the rigor of our analysis (Grodal et al., 2021). Indeed, thanks to this cyclical approach, the researchers constantly questioned their understanding of the content studied and reinforced the objectivity of the results through comparison. This approach thus ensured a nuanced and in-depth analysis of the briefs, contributing to the validity and richness of our study. During the coding process, the two researchers met nine times; two full days and seven half days.

5 RESULTS

An analysis of the 46 briefs on the climate governance reform project revealed various logics, all working toward the same goal of promoting effective climate governance. As shown in Figure 1, the data analysis revealed three main institutional logics: scientific governance, authority-based governance, and participative governance. These logics highlight the actors' concerns in the fight against climate change, ranging from the need for a science-based approach to the importance of coordination and effective decision-making.

5.1 The logic of scientific governance

The logic of scientific governance is at the heart of the implementation of green fund governance in Quebec. It is composed of several dimensions, one of which is the call for organizations to use performance indicators to ensure impartial decisions. These dimensions also become the object of reports to provide monitoring and to hold actors accountable. A comment from an industry organization (BUS #4.3) highlights the importance of performance indicators: “[I]t is essential to identify targets and performance indicators, measure their progress and report the results on a known and periodic basis.” This quote highlights the need for rigorous and transparent monitoring of actions to address climate change. This governance can be based on international indicators validated and legitimated by the International Climate Study Group, or determined according to local issues. Many associations and environmental organizations particularly emphasize the importance of these indicators to ensure effective climate governance adapted to local realities.

Another dimension of the logic of scientific governance concerns the prominence of scientists, particularly in promoting science-based decision-making in selecting projects and programs for financial support. For proponents of this approach, it is necessary to fund research and development adequately and to have scientists participate in governance structures. In the briefs we studied, many organizations supported this idea. For example, one environmental association (ENV #1.3) expressed the importance of involving experts in the decision-making process: “[M]embers of the permanent advisory committee should be appointed by a selection committee consisting of the chief scientist and members of the steering committee with specific selection criteria, particularly concerning the areas of expertise sought.” This quote emphasizes the importance of an expertise-based approach to ensuring the quality and relevance of decisions made under the government's climate action plans.

5.2 The logic of authority-based governance

Effective climate change governance requires significant coordination of government action. To do this, the state must assume its environmental responsibilities to make and implement decisions. It must ensure impartiality in its governance. Several organizations emphasize this point by referring to the need to take unpopular actions and to ensure the integrity of those actions and decisions. The following excerpt from an environmental organization's brief (ENV #1.9) illustrates this expectation: “unpopular actions will have to be taken, and the best way to ensure the authority of those actions and decisions is through popular participation in their development and a governance body independent of political power to recommend them.” Several organizations have recommend the creation of an independent body. The solution for some is to create a state-owned enterprise to reduce bureaucracy and lower the stakes of partisan decision-making. For example, one company pointed out (BUS #4.13) that “creating a state-owned enterprise responsible for implementing climate policies is necessary for the success of the fight against climate change.”

Finally, some stakeholders consider it essential that government decisions be subject to the control of the Auditor General of Quebec or the Commissioner for Sustainable Development. This third-party auditor could ensure that consistency among the choices made to fight climate change. In particular, the organizations recommend requiring the Commissioner for Sustainable Development to conduct annual audits. The proposal of a research laboratory (RES #6.1) clearly illustrates this recommendation: “The Commissioner for Sustainable Development should be required to report annually on all measures and programs related to climate objectives, including mitigation and adaptation.” As another example, a local community (AUT # 3.2) recommends that “all ministerial directives that bind relevant government departments and agencies be made available to the public so that the Minister is accountable for their enhanced role as the government's climate watchdog.” These quotes illustrate the importance of independent control and transparency in ensuring sounder climate governance.

5.3 The logic of participative governance

As its name suggests, the third institutional logic—participative governance—is characterized by a participatory approach, encompassing social dialog, attention to social justice, and a desire for concrete and effective action. The actors involved in this logic seek to transcend the divide between the environment and the economy. They view the participation of local governments as essential for a less centralizing approach to the fight against climate change. A federation representing local governments (AUT #3.3) emphasizes this perspective by saying it welcomes “the reform of the Green Fund as an opportunity to promote a less centralist approach that favors greater participation by local governments in the fight against climate change.” For the partisans of this approach, social dialog is crucial to ensuring a fair and socially acceptable energy transition.

The energy transition brings with it several workforce challenges. Attention to social justice in addressing these challenges is necessary for the acceptability of binding actions, including support measures for the most vulnerable populations. For example, the government must implement employee retraining programs. One environmental organization emphasized the importance of supporting people in this transition by “[p]roviding [them] access to conversion and training programs to ensure that the workforce has the skills and knowledge required by the new technologies.” The logic of participative governance also includes attention to the economic sector. These actors are a driving force in the fight against climate change. A group representing companies (BUS #4.9) emphasized this sector's role in Quebec's carbon inventory and the proactivity of industrial players: “Remember that industry already reduced its emissions by 25% between 1990 and 2017.”

Table 2 presents a synthesis of the three institutional logics. It includes definitions of the different dimensions of the logics and some excerpts from briefs to illustrate divergent conceptions of climate governance.

Scientific governance The centrality of science in the decision-making process |

Dimensions | Importance of performance measurements | Importance of experts in the decision-making process | Importance of research and development |

| Definitions | Emphasis on the use of performance indicators to ensure objective and fair decisions, as well as to monitor progress and hold actors accountable. | The critical role of scientific experts in decision-making is to ensure transparency and impartiality and to provide evidence. | Insistance on adequate research and development funding, allowing for the acquisition of new knowledge and the promotion of a culture of innovation to address climate challenges. | |

| Representative quotes | “Identifying targets and expected performance indicators is of utmost importance.” (ENT #4.3) | “Establish a simple, agile, expert-led management process to guide the government in all investment choices.” (TRA #2.2) | “[We] recommend that experts from the research, education, clinical medicine, and policy communities act together to find new solutions to reduce GHG emissions and that funding be allocated to such research” (RES #6.4) | |

Authority-based governance Primary emphasis on decision-making and control |

Dimensions | Government authority | Autonomous authority | Shared authority |

| Definitions | The central role of government is coordinating actions, making decisions, and implementing climate policies. | Reference to creating independent third-party agencies that make decisions autonomously, without partisan influence or bureaucratic red tape. | Stress on the importance of collaboration between the different levels of government, organizations, and actors. | |

| Representative quotes | “It is important that the minister responsible for greenhouse gas reduction targets has the ability to coordinate activities and programs.” (ENV #1.3) | “We reiterate our recommendation for the creation of an independent ‘super’ agency, which should be assigned the management of these funds.” (ENV #1.10) | “Communities must also be involved because it is only by knowing the needs of the regions that the government will find ways to implement the appropriate measures.” (AUT #3.3) |

Participative governance Voluntary stakeholder involvement for collective, action-oriented decisions |

Dimensions | Importance of including all stakeholders | Importance of a sustainable, integrative approach |

| Definitions | Emphasis on inclusion and participation of stakeholders. | Emphasis on the need to simultaneously address environmental, social, and economic issues in the fight against climate change, seeking to reconcile these objectives. | |

| Representative quotes | “Social dialogue, therefore, becomes a must to ensure that the energy transition is done fairly.” (BUS #4.4) | “That the Government of Quebec, through its Premier, declare a state of climate emergency.” “To ensure a just transition. Bold gestures and sacrifices await us.” “Businesses in the sector are also key players in achieving the government's economic development objectives.” (ENV #1.15) |

5.4 The stakeholders' positions

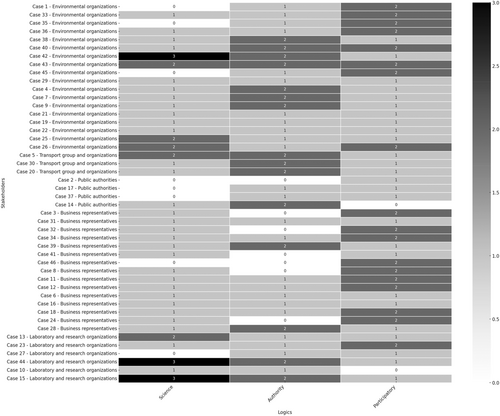

An analysis of the 46 submissions reveals a trend in the positioning of the various actors concerning the three institutional logics of governance. The heat map below presents a detailed analysis of each actor's use of the different institutional logics (science, authority, and participatory), identified by case number and type. This visualization method provides a granular view highlighting each actor's specificities for adopting these logics. The data is organized to display the distribution and intensity of logic use (Figure 2).

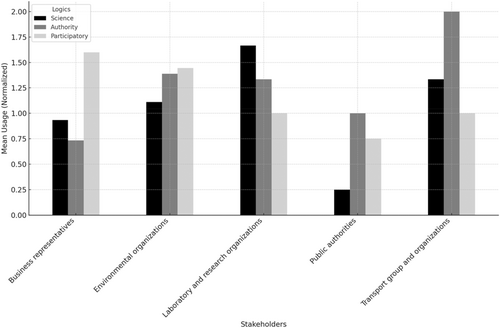

The averages were calculated to analyze the institutional logics (science, authority, and participatory) used by different types of stakeholders. Figure 3 presents a comparative analysis of the use of institutional logics for these different types of actors. This visualization highlights clear distinctions between stakeholder types regarding their propensity to adopt certain logics. It enables an analysis of the institutional preferences that might influence their strategies and behavior.

Table 3 summarizes the institutional logics favored by the different types of stakeholders. The logics are classified into priority, secondary, and subsidiary for each stakeholder category. This classification reveals the predominant orientations that characterize the institutional approaches of local public authorities, business representatives, and organizations (environmental, research, and transport). The analysis highlights the diversity of institutional priorities, illustrating how each type of actor privileges certain logics according to their specific contexts and objectives. This arrangement allows us to understand the internal dynamics of each sector and discern cross-influences and potential alignments or conflicts between the various institutional players.

| Priority | Secondary | Subsidiary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental organizations (ENV) | Proactive | Authority | Science |

| Transportation organizations (TRA) | Authority | Science | Proactive |

| Local public authorities (AUT) | Authority | Proactive | Science |

| Business representatives (BUS) | Proactive | Science | Authority |

| Research organizations (RES) | Science | Authority | Proactive |

The results presented in Table 3 indicate that many environmental stakeholders emphasized the logic of participatory governance based on the social dialog approach. Several organizations also expressed a desire for concrete and effective climate action while paying attention to social justice. The logic of authority-based governance is also essential for stakeholders expecting the government to assume its environmental responsibilities and to make concrete decisions.

By contrast, for most transportation agencies, the logic of authority-based governance is predominant, followed by the logic of scientific governance and, finally, the logic of participative governance. On the other hand, communities favor the logic of authority-based governance first, followed by the logic of participatory governance, and finally, the logic of scientific governance. Businesses, for their part, put forward the logic of participatory governance first, followed by the logic of scientific governance, and thirdly, the logic of authority-based governance. Finally, for research organizations, the logic of scientific governance is privileged in the first place, followed by the logic of authority-based governance, and last, the logic of participatory governance.

These trends highlight the different points of view of the stakeholders involved in the fight against climate change in Quebec. Environmental associations and organizations are more proactive, focusing on concrete action and social justice. At the same time, businesses are more pragmatic and seek to use their sectors to contribute to the fight against climate change. Like institutional actors, local governments emphasize the logic of authority-based governance, while the research sector emphasizes the logic of scientific governance. These different logics may seem divergent, but it is important to highlight that they can complement each other and thereby contribute to more effective global climate governance.

5.5 Conciliatory pathways to sound climate governance

Actors engaged in climate governance adopt hybridization strategies that harmonize their actions toward common objectives. This alignment, inspired by the work of McGivern et al. (2015), highlights the role of actors who have become hybrids. They integrate elements of several logics, enabling an approach that can better address the transversality and complexity of contemporary climate requirements (Reay & Hinings, 2009). These actors facilitate productive interaction between different logics by occupying roles that straddle science, management, and advocacy. For example, a scientist may take on project management responsibilities while maintaining scientific integrity to influence climate policymaking. This hybrid role enables scientific knowledge to be applied more effectively and promotes pragmatic, action-oriented management.

The identity work associated with these hybrid roles is essential, as it requires individuals to navigate between different professional identities while remaining steadfastly committed to their original expertise. This dynamic is particularly relevant to discussions of the balance between scientific imperatives, the necessities of authoritarian action, and participatory initiatives. This hybridization leads us to identify possible paths of conciliation for effective climate governance.

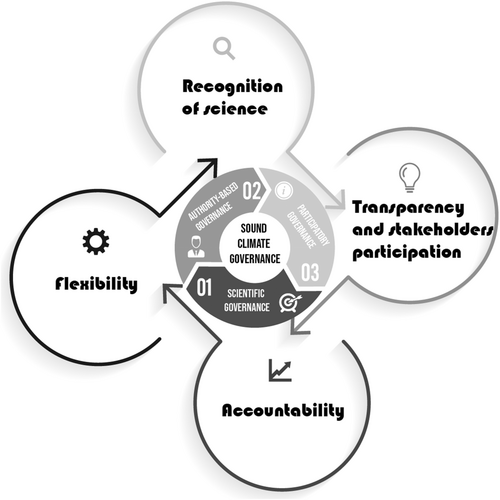

These pathways to conciliation, described in Figure 2, are based on an analysis of the proposals for improvement put forward in the briefs submitted during the public consultation. This analysis identified four fundamental principles that could link the different institutional logics while responding to the various stakeholders' concerns. These principles were identified by highlighting the convergence points between the logics and examining the stakeholders' proposals in detail.

The proposed integrative climate governance framework respects the balance between scientific imperatives, institutional authority, and stakeholder responsibility. Actors' ability to integrate and articulate these institutional logics is a major advantage when proposing solutions that respect scientific rigor and the practical constraints of the various stakeholders.

Figure 4 shows that four principles facilitate the combination of the different logics of climate governance: (1) recognition of the importance of science, (2) transparency and stakeholder participation, (3) accountability, and (4) flexibility.

The principle of recognizing the importance of science emphasizes the central role of scientific research and knowledge in climate policymaking. By recognizing the importance of science, actors can build a common foundation for understanding the impacts of climate change and developing options to address them. Research laboratories have a natural role in this area, and environmental advocacy groups can support them by providing scientific data and analysis to inform policy decisions. Businesses and industry representatives can also contribute by adopting science-based approaches and sharing information about the environmental impacts of their activities, thereby promoting the integration of different climate governance logics.

The principle of transparency and stakeholder participation emphasizes the need to include diverse people in the decision-making process and to ensure access to relevant information to enhance the legitimacy and effectiveness of climate policies. Stakeholders can contribute to transparency and participation by providing precise and objective information and by involving the groups most affected by climate change. Environmental organizations are likely to be the most active in this area. Research laboratories can promote transparency and participation by sharing their research results and involving stakeholders in the design and implementation of research projects. This inclusive approach reconciles logics by encouraging dialog and collaboration between actors.

Accountability emphasizes the need for actors to be accountable for their commitments and actions in the struggle to mitigate climate change. By establishing performance indicators and monitoring measures, actors can assess the effectiveness of climate change policies and standards and adjust their actions accordingly. Business and industry representatives are likely to be most active in this area. At the same time, the logic of authority-based governance can help enforce these measures and hold actors accountable for their implementation. Local governments also valorized accountability in their briefs. By holding actors accountable, this principle fosters collaboration and complementarity between the different logics of climate governance, thus encouraging concerted and effective action.

The principle of flexibility emphasizes the importance of adopting adaptive and responsive approaches to the challenges and uncertainty of climate change. Flexibility allows actors to adjust quickly and effectively to new information and long-term trends while adopting practices and systems based on reliable data to implement necessary measures. Business representatives, as well as transportation organizations, are focused on flexibility. By promoting adaptability and responsiveness, this central principle facilitates the conciliation of different climate governance logics, encouraging actors to work together to develop innovative and coordinated solutions to the challenges of climate change.

Each principle plays an essential role in building sound climate governance, allowing the strengths and contributions of different logics and actors to be combined. By adopting these principles, actors can work together to develop coherent, science-based, transparent, accountable, and flexible climate policies and actions, ensuring a collective and appropriate response to the growing challenges of climate change.

6 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study has highlighted three institutional logics to explain the positions of the players involved in climate governance and the possible avenues of reconciling them. These findings reflect a need for further reflection on how institutional logics can be specifically adapted to environmental and climate challenges. Indeed, there is a growing consensus in the literature on the need to develop and adapt institutional logics aimed explicitly at environmental and climate challenges. This need stems from the recognition that existing institutional frameworks often fail to fully capture environmental governance's complex and interconnected dimensions (Hoffman & Jennings, 2015; York & Venkataraman, 2010). This work highlights the importance of integrating distinct environmental perspectives within institutional logics to address climate change and sustainability issues.

In their research on environmental logics, Hoffman (2013) proposed that, as a new component of the institutional landscape, they offer a structure for understanding and organizing environment-related actions in a way that transcends the traditional boundaries of business or professional logics. This approach is supported by Whiteman et al. (2013), who suggested that integrating environmental logics into business practices can catalyze sustainable innovations, responding effectively to contemporary ecological and societal pressures.

This conceptualization of institutional logics in the study of climate governance in Quebec enables an analysis of the interactions between traditional frameworks and the specific dynamics of this region. Scientific, authority-based, and participative governance are distinguished by significant overlaps with traditional logics, while introducing unique dimensions essential to understanding how to best respond to climate change. For example, scientific governance relies heavily on professional logic, emphasizing the use of specialized expertise and knowledge to shape public policy (Friedland & Alford, 1991; Thornton et al., 2012). This symbiosis highlights the importance of empiricism and scientific rigor when formulating climate responses, transcending standard professional approaches by firmly grounding them in evidence-based practices.

On the other hand, authority-based governance has its roots in the logic of the state, emphasizing the importance of regulatory structures and governmental power in imposing climate action (Scott, 2000). This crossover illustrates how formal frameworks and authority-based directives can be mobilized to guarantee the effectiveness and adherence of environmental initiatives. Finally, participatory governance, while sharing characteristics with market and community logics (Friedland & Alford, 1991; Thornton et al., 2012), proposes integrating these elements to foster active participation and sustained innovation within communities, thereby strengthening local commitment and collective responsibility in the face of climate change.

The three logics proposed here offer a new conception of climate governance, highlighting the need for multidimensional approaches adapted to the complex challenges of climate change. Scientific governance values the role of empirical research and the need for a sound scientific basis in policy decisions, responding to the requirement for robust evidence-based interventions (Thornton et al., 2012). Authority-based governance emphasizes the importance of a strong regulatory framework and centralized management to ensure the effective implementation of climate policies (Scott, 2000), while participative governance illustrates the role of action, flexibility, and community participation (Friedland & Alford, 1991). Each of these logics enriches the discourse on climate governance by offering strategies that harness existing institutional resources and the adaptive capacities required for effective climate management. Together, they provide an integrated framework for addressing climate issues in a strategic, inclusive, and responsive way, marking an important departure from traditional, more segmented approaches. This innovative approach further allows us to understand the dynamics between institutional logics, incorporating the conciliation mechanisms and mutual adjustments that shape climate governance. This article also responds to Lounsbury et al.' (2021) call to study the governance dynamics of institutional logics and their ordering in context (Friedland & Alford, 1991; Thornton et al., 2012). This research goes beyond using logics as mere analytical tools, following in the footsteps of studies that view institutional logics as complex, constantly changing phenomena (Greenwood et al., 2011; Pache & Santos, 2013; Smets et al., 2015).

Thus, this research contributes significantly to enriching the literature on institutional logics by proposing an analytical framework that considers the complexity of interactions and conciliation processes between logics. This approach allows us to better understand how institutional logics coexist, transforming, and influencing each other in climate governance, thus offering new perspectives for understanding and managing climate-related issues. By approaching them through the lens of institutional logics and by revealing avenues for conciliation, this study contributes to the literature on climate governance and institutional logics.

Second, this work expands the knowledge of how national authorities and states contribute to climate change and the governance issues of green climate funds (Andonova & Mitchell, 2010; Bulkeley & Betsill, 2013; Jordan et al., 2015, 2018; Newell & Paterson, 2011). It highlights the importance of a multidimensional approach to climate governance, considering the three institutional logics. This study provides a better understanding of the interactions between these logics and how they influence climate governance (Andonova & Mitchell, 2010; Bulkeley & Betsill, 2013; Zeigermann, 2021). This work addresses the need, identified in the literature, to study how different actors' logics combine within climate governance by examining those actors' prior logics and interests (Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., 2020; Jordan & Huitema, 2014; Newell et al., 2012).

Third, the implications of this research are both scientific and political. Indeed, this study enriches the work of Jordan et al. (2015) and Vedeld et al. (2021) by highlighting how different logics can combine to foster effective polycentric climate governance at the national scale. It also helps policymakers better understand the motivations of the different actors involved in climate governance and identify the most efficient formats for collaboration to move toward a stronger climate governance system. By emphasizing the importance of balancing diverse logics and promoting transparency, participation, and accountability, this research contributes to the literature on developing governance mechanisms adapted to climate change's complex challenges and uncertainty (Gomez-Echeverri, 2013; Newell et al., 2012).

Finally, this study has some limitations. First, it focuses on the specific case of Quebec (Canada). It would be essential to conduct similar research in other states or regions to validate and enrich the conclusions drawn from this study. Second, while the study examines the prior interests of actors in entering governance systems, it may only capture some of the nuances of those interests and their underlying motivations. Additional qualitative research could deepen our understanding of actors and their motivations, such as by asking them about these specific determinants.

APPENDIX 1: INDUCTIVE CODING TREE

-

The logic of scientific governance

- ○

1.1 Decisions must be based on transparent indicators

- ○

1.2 Decisions must be based on expert advice

- ○

1.3 Need to support and involve scientific research

- ○

-

The logic of authority-based governance

- ○

2.1 Government leadership needed

- ○

2.2 Need for neutral third-party control

- ○

2.3 Need for a neutral decision-making body

- ○

-

The logic of participative governance

- ○

3.1 Need for collaborative and open governance

- ○

3.2 Need for climate action

- ○

3.3 Need to act for social justice

- ○

3.4 Need for action to support the economic sector

- ○