Activity budget and foraging patterns of Nubian giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis camelopardalis) in Lake Nakuru National Park, Kenya

Abstract

The activity budget of giraffe in various African populations has been studied extensively, revealing that it is affected by body size, foraging patterns, and sex. Foraging patterns show an animal's feeding choices in its environment and are influenced by resource availability, competition, and predation risk. The ability of giraffe to survive and reproduce is significantly impacted by the variation in activity budget and foraging across different ecosystems. Our study focused on evaluating the seasonal activity budgets and foraging patterns of Nubian giraffe in Lake Nakuru National Park, Kenya. We used the scan sampling method to record the activity budget of giraffe which included foraging, movement, resting, and drinking water. We then evaluated if activities varied with the seasons. A total of 11,280 activities were documented, with 4560 (40.4%) occurring during the dry season and 6720 (59.6%) during the wet season. Foraging accounted for 53% of the time budget during the dry season, but increased to 57% during the wet season. There was a slight drop in records of movement (22%; n = 995 of 4560) and resting (25%; n = 1145 of 4560) from the dry season to the wet season (20%; n = 1375 out of 6720 and 22%; n = 1515 of 6720). During the dry season, females (53%) foraged longer than males (47%), whereas males (44%) had longer resting periods than females (56%). Giraffe frequently fed on Vachellia xanthophloea (67%; n = 4136 of 6215 foraging records), Maytenus senegalensis (19%), and Solanum incanum (9%) over both seasons. Overall, seasons had little impact on giraffe activity time budgets and foraging patterns in Lake Nakuru National Park. A better insight into the behavioural patterns of this subspecies will allow managers to enhance the protection and conservation of the species and its habitat. Heavy foraging on Vachellia by giraffe at LNNP has been associated with a population decline in number, so perhaps planting more of this species in LNNP could promote a rebound in numbers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Different animals have an activity time budget that reflects physiological traits and ecological interactions (Blake et al., 2012; Norris et al., 2010). These behavioural decisions, i.e., what activities to perform and how much time to dedicate to them can affect survival and reproductive success (Gaillard et al., 2010). An animal's decision regarding foraging, movement, resting, and drinking water might reduce the risk of predation, hence enhancing chances of survival and reproduction (Lind & Cresswell, 2005; Sansom et al., 2009). Factors such as water and food availability, temperature fluctuations, seasonal changes, growth and reproduction cycles, predator avoidance, and proximity to human settlement determine how prey species allocate their time to various behaviours (Brown et al., 2023; Owen-Smith & Goodall, 2014; Svizzero & Tisdell, 2017; Xia et al., 2011). Animals modify their feeding behaviour by increasing the time spent foraging as the quality and quantity of browse decline during the dry season to maintain daily nutritional needs and survival (Adolfsson, 2009). Evaluating activity budgets of different species is essential for understanding how factors like forage variability with seasons affect their survival (Blanco et al., 2017; Estes et al., 2011).

Giraffe (Giraffa spp.) inhabit diverse habitats and consume a range of plant species such as Vachellia, Grewia, Combretum, and Commiphora spp. (Obari, 2014). Giraffe prefer Vachellia-dominated savanna woodlands characterised by evenly spaced trees and open canopies that provide ample forage (Berry & Bercovitch, 2017; Ciofolo & Le Pendu, 2002; Mahenya, 2016; O'Connor et al., 2015). Berry and Bercovitch (2017) described close to 100 plant species in the diet of a population of giraffe, although only about half a dozen make up most of the forage consumed. Giraffe can thrive in regions with scarce water resources due to their water-independent nature. However, some giraffe choose to feed near rivers to guarantee a consistent availability of food and water in all seasons (Saito & Idani, 2020; Wyatt, 1969).

Previous research has examined several aspects of giraffe behaviour, such as nocturnal behaviour (Burger et al., 2020), diurnal activity budgets (Deacon et al., 2024; Paulse et al., 2023) and the impact of seasonal changes on foraging activities (Clark et al., 2023; Pellew, 1984). Studies have shown variation in giraffe behaviour across many environments, including zoos (Fernandez et al., 2008), national parks (Lee et al., 2023; Saito & Idani, 2020), and natural habitats (Fennessy, 2009). These variations can be influenced by factors like sex differences (Bashaw, 2011; Ginnett & Demment, 1997), body size (du Toit & Yetman, 2005), anthropogenic influences (Scheijen et al., 2021), and proximity to human settlements (Bond et al., 2021). Giraffe adapt their foraging time according to food availability (Pellew, 1984), habitat utilisation patterns (Saito & Idani, 2020), and the impacts of feeding opportunities on reducing abnormal behaviour such as oral stereotypy (Enevoldsene et al., 2022). While giraffe research has been conducted throughout Africa, no equivalent research has been conducted to determine the activity pattern of Nubian giraffe (Giraffa c. camelopardalis) in Lake Nakuru National Park (LNNP) due to significant variations in environmental conditions.

This study seeks to better understand the ecological dynamics of LNNP, an enclosed and distinctive conservation area located on the periphery of an urban centre. Research on giraffe foraging at LNNP provides additional insights into the dietary flexibility and adaptability of giraffe, given that LNNP is on the periphery of a sprawling urban city. Urban sprawl and obstruction of giraffe dispersal patterns may limit their ability to move to suitable habitats and resources, affecting their survival and population dynamics (Bond et al., 2023). The park, like other enclosed ecosystems, has unique challenges, like habitat deterioration, competition for resources, heightened vulnerability to environmental shifts and increased risk of predation (Bond et al., 2023; Brenneman et al., 2009; Dharani et al., 2009; Gathuku et al., 2021; Muller, 2018). Giraffe need a large home range to acquire resources and restricting them to a park can affect their activity time budget and overall survival (Brenneman et al., 2009; Obari, 2014; van der Jeugd & Prins, 2000). In the Tarangire-Manyara region of northern Tanzania, adult giraffe had an average home range size of 114.6 km2 for females and 157.2 km2 for males (Knüsel et al., 2019). The portion of LNNP not encompassed by the lake is around 134 km2 (Onyango, 2020). This is smaller than the typical home range size of females, although home range size is determined by resource availability (Knüsel et al., 2019). Enclosed habitats can prevent giraffe from having access to quality forage, exacerbate intraspecific competition, and/or increase the risk of predation, (Brenneman et al., 2009; Muller, 2018; Pendu & Ciofolo, 1999; van der Jeugd & Prins, 2000). Furthermore, understanding the behaviour and foraging patterns of giraffe is crucial for developing successful conservation measures due to the potential genetic isolation of giraffe populations in the region (Fennessy et al., 2013).

There are approximately 1042 Nubian giraffe in Kenya, making it the most at-risk subspecies in the country (Muneza et al., 2024). Most of the Nubian giraffe populations in Kenya are isolated in enclosed areas (Brenneman et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2023; Dagg, 1962). Habitat degradation has reduced the Nubian giraffe habitat by 37% in sub-Saharan Africa and 75% in Kenya (O'Connor et al., 2019). However, Bercovitch (2020) questioned these findings owing to methodological concerns. The factors affecting the Nubian giraffe activity time budget and foraging patterns in Kenya are not well known. This study aimed to evaluate how seasonal variations and sex differences could impact the activity time budget and foraging behaviour of the Nubian giraffe in LNNP, Kenya, due to the limited information available and the significance of precise data for conservation and management decisions.

2 STUDY AREA

LNNP covers 188 km2 in the Rift Valley in Nakuru County, Kenya and is situated between 000 18' S and 000 30' S latitude and 360 03′ and 360 07′ E longitude, at an elevation of around 1759 metres above sea level (KWS, 2011). The park features a central lake that covers an area of approximately 54 km2. The park experiences an average annual rainfall of 750 millimetres, evenly distributed between April and June and from October to December. The dry seasons occur from July to September and from January to March. The daily maximum temperature during the dry season is 28°C, while the minimum is 18°C. The average daily minimum and maximum temperatures during the wet season are 14°C and 24°C, respectively (KWS, 2011).

The park comprises grasslands, woodlands, and bushed woodland as its main habitat types. Vachellia woodlands are widespread and associated with high water table areas (Figure 1). Vachellia seyal, Vachellia hockii, Vachellia xanthophloea, Vachellia gerrardii and Vachellia abyssinica, are the predominant woody species in Vachellia woodland. Additional species found in Vachellia woodland include Achyranthes aspera, Solanum incanum, and Urtica massaica which are short bushes as well as Grewia similis, Rhus natalensis, Senecio lyratipartitus, Cassia bicapsularis, and Vernonia auriculifera (Mutangah, 1994). The park's second-largest habitat consists of bushed woodlands interspersed with Vachellia woodland. The primary shrub in the bushed woodlands is Tarchonanthus camphoratus, while the main grasses are Cynodon dactylon and Sporobolus spicatus. The main trees include Vachellia xanthophloea and Vachellia gerrardii (Mutangah, 1994). Open grasslands are located in the sedimentary plains to the north and south of the lake. The grass species present are Chloris gayana and Hyparrhenia hirta, along with Lippia ukambensis and Lantana trifolia bushes. The habitat contains scattered trees and shrubs such as Maerua triphylla, Maytenus senegalensis, Cordia ovalis, Tarchonanthus camphoratus, and Rhus natalensis (Mutangah, 1994)(Data S1).

The park is home to around 400 bird species, including large colonies of lesser (Phoeniconaias minor) and greater (Phoenicopterus roseus) flamingos (McClanahan et al., 1996; Ogutu et al., 2017). The park hosts a diverse array of over 70 mammalian species, including grazers such as hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus), Thompson's gazelles (Eudorcas thomsonii), Bohor reedbuck (Redunca redunca), Burchell's zebras (Equus quagga), warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus) and impala (Aepyceros melampus) along the lake's shoreline. Vachellia woodlands are inhabited by Nubian giraffe, bushbuck (Tragelaphus sylvaticus), black rhino (Diceros bicornis); grazers like cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer), and white rhino (Ceratotherium simum); mixed feeders like olive baboons (Papio anubis), and colobus monkey (Colobus guereza) and predators like leopard (Panthera pardus) and lion (Panthera leo). Bushed woodlands provide habitats for many grazers such as eland (Taurotragus oryx), bushbuck, impala, Chandler's mountain reedbuck (Redunca fulvorufula) and dik-dik (Madoqua kirkii). The cliffs and escarpments are home to yellow-spotted rock hyrax (Heterohyrax brucei), klipsringer (Oreotragus oreotragus), and Chandler's reedbuck, which are both grazers and browsers (KWS, 2002; Mutangah, 1994).

The population trend of giraffe in LNNP has been declining with a variation in recovery. The population decreased from 153 to 62 between 1998 and 2003 (Brenneman et al., 2009), then rose to 89 (Muller, 2018). The current population is estimated to be between 95 and 120 Nubian giraffe (Muneza et al., 2024). A study by Muller (2018) indicated that a high lion density of 30 lions per 100 km2 in the park could endanger giraffe through predation and impact their habitat selection. Unpublished data show that there were 65 lions in 2002 and 56 lions in 2010 (Bett et al., 2010; KWS, 2002). However, routine ground counts conducted between 2010 and 2017 revealed an infrequent sighting of six to sixteen individuals (Bett, unpublished data). In 2017, surveys were paired with a spatially explicit capture–recapture (SECR) method that recorded 16 lions (Elliot et al., 2020) and proposed that previous approaches may have led to double-counting, rather than indicating a drop in the population.

2.1 Methods

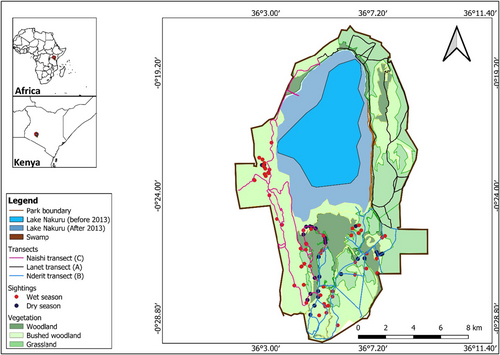

2.1.1 Giraffe activity observations

We completed pre-survey training in November 2018 to ensure consistent and reliable recording of sightings. The park was divided into three equally sized blocks (A, B, and C) for surveys conducted along three transects: Lanet (50 km) in block A, Nderit (49 km) in block B, and Naishi (49 km) in block C. The blocks contained heterogeneous vegetation, including Vachellia woodland, grassland, and bushed woodland as the main types. We used roads that cut across each block as sampling lines (Figure 1).

Seven people participated in the sampling process. Three team members monitored giraffe behaviour; two took photos, and two identified plant species browsed by giraffe. We observed giraffe behaviour during the dry season from February 13 to 15 and February 20 to 22 and during the wet season from May 31 to June 2 and July 11 to 13 in 2019. Each data collection period spanned 3 days. We selected a block at random from blocks A, B, and C, and then chose the first herd we encountered from that block, sampling one block per day. Four observations were made daily, two in the morning (08:00–09:00 and 11:00–12:00) and two in the afternoon (14:00–15:00 and 17:00–18:00). Giraffe are typically most active during the early morning (07:00–09:30) and late afternoon (15:00–19:00), with less activity throughout the afternoon hours (14:00) (Leuthold & Leuthold, 1978a). Therefore, observation hours were randomly chosen to fall within these times.

We used a scan sampling method to observe Nubian giraffe daily activity, maintaining a distance of 50–100 metres from the research vehicle to avoid disturbing the animals (Altmann, 1974). We waited for 5 minutes before commencing observations to give the giraffe to acclimate to our presence. Each hour, we performed eight scans, (time taken watching a herd and writing down their activities), each lasting 5 min followed by a 20 min break after four scans. Every 5 min, three people observed and recorded the behaviour of each giraffe in the herd. The giraffe were scanned in a consistent order during the subsequent scans within each hour (left to right or right to left), and the average of the observation from the three people was calculated. We recorded the date, time, season (wet or dry), habitat type (Vachellia woodland, bushed woodland, or open grassland), herd size, sex, and location (GPS coordinates) at the beginning of the observation. Recorded activities included moving (running and walking), resting (lying down, standing, and socialising), foraging (biting or using the tongue to pull a leaf or twig), licking soil, and drinking. Adult giraffe were exclusively observed to enhance precision.

We recorded the plant species selection by giraffe in each herd in 5-minute scan intervals and defined a foraging record as one plant species consumed by one giraffe during one scan. We identified the plant species selected by each giraffe based on named species, photographs, and illustrations.

2.2 Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to analyse the activity budget and foraging patterns of giraffe in the study area. We calculated the percentage of time spent on each activity by averaging the frequency of each activity per hour for each season. We aggregated the foraging data for each plant species consumed each hour and expressed it as a percentage of all feeding records for that specific hour, and subsequently for each season. We calculated the percentage of occurrence of the various activities per hour and season, and the percentage of occurrence of a plant species in the foraging records for each season. We conducted a Mann–Whitney U test to evaluate the effect of seasonality on activity budget, seasonality and plant species in giraffe diet, and sex on activity budget. We also used the Kruskal–Wallis test to assess the effect of habitat type on the activity budget of giraffe. The dependent variables of the study were the giraffe activities (foraging, resting, moving, and drinking water) and plant species in the giraffe diet, whereas the independent variables included sex, time, season, and habitat types with the level of significance set at 0.05 (Zar, 1996). We conducted all statistical analyses using STATA version 12.0.

3 RESULTS

The findings of the study indicate significant variations in giraffe foraging behaviour between the dry and wet seasons. Foraging records of giraffes increased from the dry season to the wet season. Additionally, female giraffes were found to forage more frequently than male giraffe during the dry season. Habitat preference was also noted, with giraffes foraging more frequently in the Vachellia woodland during the dry season compared to open grassland and bushed woodland. Furthermore, giraffes foraged on eight plant species during both seasons, showing dietary diversity. Notably, there was a marked increase in the selection for Maytenus senegalensis in the wet season.

3.1 Nubian giraffe diurnal activities in the dry and wet seasons

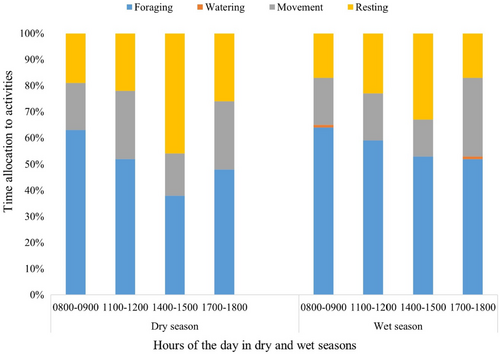

During the dry season, foraging records accounted for 53% of the activity records (Table 1). Foraging records decreased from 63% in the early morning to 52% at noon and further reduced to 38% in the afternoon. Foraging records increased to 48% in the evening (Figure 2). Movement records were lowest in the afternoon at 16%, whereas resting records were lowest in the morning at 19% (Figure 2). There were no records of giraffe drinking water during the survey period.

| Activities | Dry season | Wet season | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4560 | N = 6720 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Foraging | 2420 | 53 | 3795 | 57 | .091 |

| Moving | 995 | 22 | 1375 | 20 | .307 |

| Resting | 1145 | 25 | 1515 | 22 | .315 |

| Watering | 35 | 1 | |||

Giraffe primarily engaged in foraging during the rainy season, representing around 57% of their activity (Table 1). Foraging records accounted for more than 50% of the observations while resting and moving made for 22% and 20%, respectively. From morning to evening, foraging records decreased progressively from 64% in the morning to 59% to 53% to 52% in the evening (Figure 2). Just like during the dry season, movement records were lowest in the afternoon at 14%, while the lowest resting records were made in the morning and evening. Only 1% of wet-season mornings and evenings were spent drinking water (Figure 2).

We used the Mann–Whitney U test to assess the variation in giraffe activities across different seasons. We found a marginal increase in the foraging records of giraffe from the dry to the wet season accounting for 53%–57% of the total activity records (p = .09). Movement and resting records decreased from the dry to the wet season from 22% to 20% and 25% to 22% of the total, respectively. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p = .31 and p = .32, respectively) (Table 1). Afternoon resting records were highest in both seasons, with a greater increase observed during the dry season.

The Mann–Whitney U test results showed a significant difference between the frequency of giraffe foraging and resting during the dry season, based on their sex (p = .023 and p = .024, respectively) (Table 2). Female giraffe foraged more frequently (53%) compared to male giraffe (47%), while male giraffe rested more often (56%) compared to female giraffe (44%). There was no statistically significant variation in the frequency of movement of female and male giraffe throughout the dry season. No notable difference was seen in the activity budget of female and male giraffe during the wet season (Table 2).

| Seasons | Activity | Sex | n | Mean | % | U | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | Foraging | Female | 1705 | 22.14 | 53 | 1046.5 | −2.37 | .023** |

| Male | 715 | 19.32 | 47 | |||||

| Moving | Female | 665 | 8.64 | 49 | 1383 | −0.26 | .804 | |

| Male | 330 | 8.92 | 51 | |||||

| Resting | Female | 710 | 9.22 | 44 | 1051 | −2.34 | .024** | |

| Male | 435 | 11.76 | 56 | |||||

| Wet | Foraging | Female | 2845 | 22.58 | 50 | 2644.5 | −0.01 | .997 |

| Male | 950 | 22.62 | 50 | |||||

| Moving | Female | 1005 | 7.98 | 48 | 2338 | −1.17 | .261 | |

| Male | 370 | 8.81 | 52 | |||||

| Resting | Female | 1155 | 9.17 | 52 | 2454 | −0.73 | .484 | |

| Male | 360 | 8.57 | 48 |

- **p < .05.

3.2 Nubian giraffe diurnal activities in different habitat types

Giraffe were predominantly found in the Vachellia woodland during both the dry season (60%) and wet season (63%) (Table 3). Open grassland and bushed woodland followed in order of most frequented habitats in the dry (22% and 18%) and wet seasons (21% and 16% (Table 3).

| Activities | Habitat types | Dry season N = 4560 | Wet season N = 6720 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | χ 2 | p | n | χ 2 | p | ||

| Foraging | Acacia woodland | 1450 | 5.73 | .06 | 2445 | 3.12 | .21 |

| Open grasslands | 495 | 785 | |||||

| Bushed woodlands | 475 | 565 | |||||

| Movement | Acacia woodland | 575 | 2.56 | .23 | 835 | 1.36 | .51 |

| Open grasslands | 260 | 305 | |||||

| Bushed woodlands | 160 | 235 | |||||

| Resting | Acacia woodland | 735 | 1.89 | .39 | 940 | 0.43 | .81 |

| Open grasslands | 245 | 305 | |||||

| Bushed woodlands | 165 | 270 | |||||

During the dry season, foraging records were higher in Vachellia woodlands at 60% compared to the open grassland at 21% and the bushed woodland at 19% (Table 3). The Kruskal–Wallis test results showed a marginal difference between foraging and habitat types in the dry season (p = .06) (Table 3). During the study period, we observed that giraffe exclusively inhabited the southern half of the park throughout both the dry and wet seasons (Figure 1).

3.3 Plant species in giraffe diet in dry and wet seasons

We observed that giraffe foraged on Vachellia xanthophloea, Maytenus senegalensis, Solanum incanum, Maerua triphylla, Vachellia gerrardii, Vachellia abyssinica, Rhus natalensis, and Grewia similis (Table 4). In both seasons, Vachellia xanthophloea, Maytenus senegalensis, and Solanum incanum contributed to the bulk of the giraffe diet (Table 4).

| Plant species | Dry season | Wet season | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2420 | N = 3795 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Vachellia xanthophloea | 1743 | 72 | 2393 | 63 | .27 |

| Maytenus senegalensis | 313 | 12 | 896 | 23 | .01** |

| Solanum incanum | 243 | 11 | 267 | 8 | .48 |

| Maerua triphylla | 57 | 2 | 89 | 2 | |

| Vachellia gerrardii | 39 | 2 | |||

| Vachellia abyssinica | 59 | 2 | |||

| Rhus natalensis | 91 | 2 | |||

| Grewia similis | 24 | 1 | |||

- **p < .05.

Grewia similis and Vachellia gerrardii were only browsed in the dry season, while Vachellia abyssinica and Rhus natalensis were browsed in the wet season (Table 4). We used the Mann–Whitney U test to determine whether plant species in the giraffe diet were significantly different in the dry and wet seasons. Selection for Maytenus senegalensis increased significantly from 12% in the dry season to 23% in the wet season (p = .01) (Table 4).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Activity budget for Nubian giraffe in Lake Nakuru National Park during the dry and wet seasons

Giraffe behaviour and activity patterns have been extensively researched, including their foraging patterns (Berry & Bercovitch, 2017; Deacon et al., 2023; Paulse et al., 2023). Multiple studies have shown a clear seasonal difference in giraffe activity budgets, with higher foraging rates during the wet seasons (Deacon, 2015; Deacon et al., 2023; Mahenya et al., 2016; Paulse et al., 2023). In the current study, we found a marginal seasonal difference in foraging between the dry and wet seasons, and no seasonal influence on resting and movement of the Nubian giraffe in LNNP. The disparity in findings prompts questions and suggests additional research to understand the reason for data divergence from previous studies. It is essential to note that individual studies may have limitations and might not always capture the full spectrum of seasonal variation in giraffe behaviour at individual and population levels. Additionally, variables like sample size, study duration, or the specific location of the study site can influence the contrasting findings. The limited number of days spent in the field was a constraint on the study. Despite these limitations, the sampling methods were chosen to capture a representative snapshot of the giraffe activity time budget within the constraints of the study's timeline and resource availability.

Giraffe showed significant sex-dependent differences in foraging and resting activities in the dry seasons. Females foraged more frequent than males, whereas males had longer resting periods than females. Males were recorded resting more often than females, despite their bigger size, as indicated by various studies (Brand, 2007; Dagg, 1962; Paulse et al., 2023). Male individuals can optimise their energy intake by feeding in taller patches on tree species with higher leaf biomass (Brand, 2007). Other factors that could lead to the difference in foraging and resting activity between males and females include, reproductive requirement, basal metabolism, and the ability to efficiently consume low-quality food to meet their energy demands more quickly than females (Parker, 2004; Paulse et al., 2023). We assume that male giraffe exhibited resting behaviour more frequently due to reduced foraging time, allowing for more opportunities to engage in other activities (resting and moving) (Paulse et al., 2023).

4.2 Nubian giraffe diurnal activity time budget in different habitat types of Lake Nakuru National Park

During the dry season, the western side of the lake, characterised by a bushed woodland habitat, was predominantly used, whereas it was largely avoided during the wet season. Giraffe primarily inhabit Vachellia woodlands during dry periods and spend the least amount of time in open grassland as also observed by Saito and Idani (2020). The bushed woodland habitat is characterised by fewer Vachellia xanthophloea trees with expansive canopies that provide more shade compared to the other habitat types (Dharani et al., 2009). Resource availability and diet quality are crucial factors influencing giraffe home ranges and habitat use, especially during periods of scarcity (Leuthold & Leuthold, 1978a, 1978b; Frost, 1996; Saito & Idani, 2020; Deacon & Smit, 2017). For instance, giraffe in Tsavo East National Park preferred habitats near rivers during the dry season and deciduous woodlands in the rainy season (Leuthold & Leuthold, 1978a, 1978b). Valeix et al. (2008) discovered that giraffe in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, avoided areas with little shade during hotter periods when solar radiations were at their peak. Giraffe in Katavi National Park, Tanzania, used miombo woodland during the dry season for resting due to its ample shade and capacity to accommodate larger groups (Saito & Idani, 2020). Further, other herbivores, including the giraffe, were seen to move to more open areas when wind intensity was higher for evapotranspiration-related heat loss (Valeix et al., 2008).

Our results also showed that giraffe avoided the northern part of the park. Giraffe, just like other wild species, select habitats based on features such as the topography, and the interactions between the animals and the habitat (Godvik et al., 2009; Thurfjell et al., 2017; van Beest et al., 2016). The activity time budget and home range of wildlife, especially prey species, can be affected by the available resources, the presence of competitors, and the risk of predation, among other factors (Knüsel et al., 2019; van Beest et al., 2011). In our study area, the northern part of the park is characterised by hilly and rocky terrain, posing challenges for giraffe to inhabit the area. This is also exacerbated by the increased water levels of Lake Nakuru, which have reduced the habitat available for giraffe in the north-western part of the park (Figure 1). The narrow strip of habitat left is also close to human settlements and the fence that was erected to keep out poachers, hence increasing the likelihood of the area being avoided.

4.3 Forage species in Nubian giraffe diet in dry and wet seasons

Giraffe foraged not only on the leaves of Vachellia xanthophloea but also on the bark, causing debarking, a behaviour that is caused by nutrient deficiency in an animal's diet (Ihwagi et al., 2012). Deacon (2015) noted that giraffe in the Kalahari region of South Africa selected plant species in the following order: Vachellia erioloba, Senegalia mellifera, Ziziphus mucronata, and Boscia albitrunca in decreasing order of selection. Milewski and Madden (2006) recorded that giraffe at Game Ranching Limited in Kenya spend the longest period feeding on Vachellia drepanolobium, Vachellia seyal, and Balanites glabra. Viljoen (2013) reported that 80% of the diet of a giraffe in the southwestern region of Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa, consists of Vachellia haematoxylon. Vachellia species were seen to have the most nutritive value among 14 woody species in Zambezi National Park in Zimbabwe, with high in vitro gas production (IVGP), low acid detergent fibre (ADF), and low condensed tannin (CT) concentration, hence preferred by giraffe (Mandinyenya et al., 2019). All these observations confirm the results from this study relating to the high selection of Vachellia species by giraffe.

Excessive foraging on Vachellia xanthophloea by giraffe in LNNP was also seen from the debarking of the species, which threatens the plant species, ecosystem, and the herbivores that utilise it. Brenneman et al. (2009) stated that climatic events and the decline in flora in LNNP have led giraffe to forage more on Vachellia species, thus reducing the amount of quality forage. Giraffe population decline is caused by an increase in competition for the reducing browse species, as noted by Brenneman et al. (2009)). Furthermore, since 2013 the water levels of Lake Nakuru have been increasing, submerging a part of the park that has plant species fed on by giraffe. Additionally, the population of giraffe in the park has been observed to increase in recent years. Nonetheless, further research is required to determine the effects of over-browsing on Vachellia species and its impacts on the giraffe population in LNNP. Giraffe numbers are increasing despite the ‘over browsing’ of Vachellia species and the presence of predators. Researchers need to find out whether there are enough different types of Vachellia species to sustain the giraffe population and whether giraffe get enough nutrients to supplement what they do not receive from Vachellia trees.

Giraffe foraged more on Maytenus senegalensis in the wet season compared to the dry season. Maytenus senegalensis is deciduous, thus reducing the amount of available browse for giraffes during the dry season while producing new leaves and flowers on the onset of rain (Dziba et al., 2003; Singh & Kushwaha, 2016). Further, Maytenus senegalensis has known medicinal values in human beings including anti-leishmanial, antiplasmodial, antiparasitic, anti-helminthic, and anti-inflammatory properties (da Silva et al., 2011; Zangueu et al., 2018). We suggest that the Nubian giraffe in LNNP could be foraging on Maytenus senegsalensis as a form of self-medication. However, further research is needed to understand the medicinal value of the species to the giraffe and to better understand the giraffe forage choice.

Solanum incanum ranked third in the giraffe diet even though it is considered a bush encroacher, toxic to livestock, a major threat to grazing, and a threat to native vegetation (Lusweti et al., 2011). The inclusion of this species in the giraffe diet could be a pointer that the woody species that giraffe feed on in the park may be lacking important minerals and nutrients required for survival (Sbhatu & Abraha, 2020). Other invasive or alien species foraged by giraffe include Tamarix ramosissima and Atriplex nummularia in the Little Karoo, South Africa (Gordon et al., 2016), and Lantana camara in Nairobi National Park (Obari, 2009). Foraging on invasive species can indicate the potential positive impacts these species can have on the environment and wildlife species (Chapman, 2016). Similarly, Bonanno (2016) reported that the possible benefits of invasive species are unreported and that removing them indiscriminately may not be a suitable management action.

Our findings indicate that sex significantly influences the foraging behaviour of giraffe, with females allocating more time to feeding. Our investigation also found a distinct spatial use of habitat types in LNNP among giraffe in the park. Giraffe were seen to avoid the northern section of the park throughout both dry and rainy seasons, preferring to primarily forage in the western part during the dry season. Resource availability and vegetation distribution are key elements that impact giraffe activity in the park. Lake Nakuru's rising water levels have submerged approximately 2 kilometres of the park, decreasing the giraffe's habitat. If their survival in the park is further endangered, translocation is a viable alternative to ensure their protection. The findings enhance our comprehension of giraffe behaviour and can guide conservation initiatives focused on securing appropriate habitats and resources for both male and female giraffe.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Consolata G. Gitau: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); software (lead); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead). Arthur B. Muneza: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); project administration (supporting); resources (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (lead). Judith S. Mbau: Conceptualization (supporting); resources (supporting); supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (lead). Robinson K. Ngugi: Conceptualization (supporting); methodology (supporting); project administration (supporting); resources (supporting); supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); writing – review and editing (lead). Emmanuel ngumbi: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (lead); project administration (supporting); resources (supporting); validation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI) for granting me a research permit. Special thanks to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) for logistical support. We also thank Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) researchers from Lake Nakuru and Hell's Gate National Parks for their support during field data collection and the identification of woody plant species.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the African Fund for Endangered Wildlife (AFFEW) in Kenya and the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Dryad at https://datadryad.org/stash/share/HJlY2b3iGv2I_ZVvATUhyTnVjJyJBBDAnS4iPKHBNw8