Vitamin A: It's role in cosmeceuticals for antiaging

Abstract

Topical retinoids are among the most well-studied and widely used cosmeceutical ingredients. Topical retinoids have skin rejuvenating benefits and can soften fine lines and wrinkles, lighten mottled hyperpigmentation, improve skin roughness, sallowness, and overall appearance of photoaged skin. Retinoic acid or tretinoin remains favored among dermatologists because there are a plethora of well-designed clinical trials confirming its efficacy as a topical therapy for treating aging skin. In contrast, cosmeceutical retinoids are regulated as cosmetics and in general are not subjected to the same degree of scientific rigor as prescription retinoids. Despite this difference, there are studies confirming the antiaging benefits of cosmeceutical retinoids and studies comparing their efficacy and tolerability to tretinoin. This review will focus on over-the-counter retinoids including retinol, retinaldehyde, retinyl esters, adapalene, and novel retinoid molecules. Studies on pharmacokinetics, mechanisms of action, clinical benefits, and tolerability will be reviewed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cosmeceuticals are over-the-counter skincare products that contain active ingredients that are beneficial for skin. Common cosmeceutical actives include antioxidants, botanical extracts, peptides, growth factors, hydroxy acids, moisturizing, and skin-lightening ingredients.1 Retinol and its derivatives, referred to as retinoids, are among the most sought-after and well-studied cosmeceutical ingredients. Retinoids include natural and synthetic derivatives of vitamin A. Natural retinoids include retinol (ROL), retinaldehyde (RAL), retinyl esters (REs), and retinoic acid (RA).2, 3 Synthetic retinoids include adapalene, bexarotene, tazarotene, and alitretinoin.4 Retinoids have diverse biologic activity and have been studied and used for treatment of acne, psoriasis, hyperpigmentation, wound healing, hyperkeratotic disorders, rosacea, striae, hair growth, and aging skin.5 This review will focus only on cosmeceutical retinoids found in over-the-counter products to treat aging skin.2, 3

2 SKIN AGING

Skin aging is the result of the combined effects of intrinsic and extrinsic aging.6, 7 Intrinsic aging is a natural degeneration of the skin that occurs with advanced age. Intrinsically aged skin is thin, fragile, pale, finely wrinkled, and exhibits poor wound healing.8 Extrinsic aging is caused by exposure to environmental factors including solar radiation, pollution, and cigarette smoke.9 Extrinsically aged skin is characterized by deep coarse wrinkles, mottled pigmentation, lentigines, telangiectasia, roughness, sallowness, and laxity.8 It is important to note that extrinsic aging in darker Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI has a unique phenotype. Wrinkles are generally not apparent in darker skin types until over the age of 50 and hyperpigmentation including uneven skin tone and dark spots predominate.10 Additionally, deeper pores are more common in these patients.10

Chronic ultraviolet light exposure is the major factor responsible for extrinsic skin aging. Both ultraviolet B (UVB) and ultraviolet A (UVA) play a role in photoaging.11 UVA is considered the more important wavelength since UVA penetrates deeper into the dermis and is at least 10 times more abundant than UVB at the earth's surface.12 UVA mediates its deleterious effects on skin primarily through oxidative stress. Reactive oxygen species triggered by UVA exposure damage cell membranes, mitochondria, and DNA directly.11 Oxidative stress also induces redox-sensitive transcription factors such as activator protein 1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-кβ).7, 13 AP-1 is responsible for the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that break down collagen. In addition, UV exposure causes an inhibition of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway causing a decrease in gene expression for types I and III procollagen and a reduction in collagen production. These combined effects result in a net loss in dermal collagen that manifests clinically as wrinkling. NF-кβ upregulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines that play a role in skin aging.13, 14

Extrinsically aged skin has distinct histologic features when compared to intrinsically aged skin. Intrinsically aged skin is characterized by thinning of the epidermis and flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction.15 There is a decrease in epidermal cell turnover which may contribute to poor wound healing and slower desquamation. Melanocyte density and Langerhans cells decrease with advancing age. The dermis shows a reduction in the number of fibroblasts and collagen fiber bundles. In addition, there is an increase in the ratio of type III to type I collagen in naturally aged skin. In contrast, early photoaged skin shows epidermal thickening with acanthosis while more advanced photoaging causes atrophy of the epidermis with a flattening of the epidermal-dermal junction.11, 15 Nuclear atypia may be seen in keratinocytes and melanocytes after long-term UV exposure.16 The dermis shows an accumulation of altered elastotic material, that is amorphous, thickened, and nonfunctional. This finding, called solar elastosis, is a hallmark of photoaged skin.17, 18 There is an increase in glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) associated with this abnormal elastotic material. The dermis also shows a reduction in other extracellular matrix components including disorganization and fragmentation of collagen fibrils. There may be hyperplasia of sebaceous glands and ectatic blood vessels seen in the dermis of photoaged skin.

3 THE HISTORY OF TOPICAL RETINOIDS

Retinoic acid or tretinoin was first studied for the treatment of acne and was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1972.5, 19 Anecdotal reports that fine lines and wrinkles were improving in adult acne patients treated with tretinoin led Albert Kligman and others to study the antiaging effects of tretinoin.20-22 In an early study, Kligman et al. treated subjects with photoaged skin with tretinoin 0.05% cream or a bland moisturizer.20 Forearms treated for 3 months with 0.05% tretinoin cream demonstrated histologic changes not seen in controls including epidermal hyperplasia, dispersion of melanin, improvement in epidermal atypia, eradication of actinic keratoses, new collagen formation in the dermis, and angiogenesis. Photodamaged facial skin showed even more dramatic clinical improvement and histologic changes after tretinoin 0.05% cream treatment.20 The investigators suggested that topical tretinoin was at least partly capable of reversing the structural damage of excessive light exposure and may be helpful for mitigating the photoaging process.

Subsequently, numerous clinical studies have confirmed that topical tretinoin improves photoaged skin including mottled hyperpigmentation, lines and wrinkles, sallowness, and skin roughness.23-26 Tretinoin was ultimately reformulated in an emollient cream base and studied for treating photoaged skin. Olsen et al. conducted a multicenter, double-blind clinical study to evaluate the efficacy of 0.01% and 0.05% tretinoin emollient cream.27 Both strengths were found to be safe and clinically effective for treating photoaged skin and wrinkles as confirmed by skin replica analysis. In 1995, the Food and Drug Administration approved tretinoin 0.05% emollient cream (Renova®) as the first prescription medication with an indication for treating photoaged skin and wrinkles.5

Tretinoin has also been studied for treating photoaging skin in patients with darker skin types. A 40-week, double-blind, randomized trial of 45 Chinese and Japanese patients demonstrated that 0.1% tretinoin cream significantly lightened hyperpigmentation due to photoaging compared to vehicle control (p < 0.05%) as measured by colorimetry.28 90% of the subjects in the test group showed lighter or much lighter pigmentation on the hands and face after tretinoin whereas only 33% showed improvement in the vehicle group (p < 0.0001). Erythema, scaling and burning occurred in 91% of the patients in the test group although no patient dropped out. Seven patients required temporary discontinuation of tretinoin due to retinoid dermatitis. Histology confirmed a 41% reduction in epidermal pigmentation in tretinoin-treated patients and a 37% increase in pigmentation in vehicle controls (p = 0.0004).28 Studies such as this are important so that dermatologists can reassure patients that retinoids are safe and effective in all Fitzpatrick skin types and ethnicities.

Despite its confirmed skin rejuvenating benefits, topical tretinoin is limited by its propensity to cause skin irritation or retinoid dermatitis.29 Retinoid dermatitis is characterized by redness, peeling, and flaking and occurs when supraphysiologic doses of retinoic acid are applied to the skin. This results in an upregulation of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor and amphiregulin causing basal cell proliferation, epidermal hyperplasia, and stratum corneum desquamation.29 Barrier dysfunction and cytokine release ensue causing redness. It is of interest that studies have demonstrated that higher concentrations of tretinoin are no more effective than lower concentrations for improving photoaged skin although higher concentrations are significantly more irritating.30 Although retinoid dermatitis is viewed as an indicator of skin penetration and efficacy, it is primarily an epidermal phenomenon and not related to the major skin rejuvenating benefits of RA which occur in the dermis.29 Retinoid dermatitis is generally self-limited but there are many patients who are intolerant of tretinoin and seek more gentle options.

4 COSMETIC RETINOIDS

In the mid-1990s formulators successfully stabilized retinol in cosmetic formulation.3 Delivery systems such as microsponges and liposomes have been used to enhance stability and deliver retinol more gradually to the skin.31, 32 In addition, packaging such as airless pumps and tubes were used to extend the shelf-life of cosmetic retinoids to 2 years.3 Retinol-based cosmeceuticals fast became a “go-to” option for consumers since they could be purchased without a prescription and were far more tolerable than tretinoin.

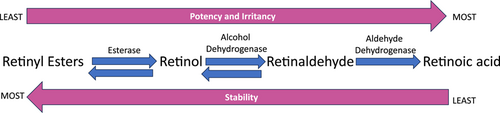

Today, there are three basic forms of vitamin A found in cosmeceuticals, retinyl esters including retinyl palmitate, retinyl propionate and retinyl acetate, retinol, and retinaldehyde.2, 33 (Table 1) The rationale behind their use is that these molecules are precursors to retinoic acid, the active form of vitamin A within the cell.2 Accordingly, REs, ROL, and RAL differ in efficacy, potency, and propensity to cause retinoid dermatitis (Figure 1).3 Retinyl esters are the most stable but least potent of the natural retinoids followed by retinol and retinaldehyde in that order.3, 34 In contrast, retinaldehyde and retinol are more likely to cause retinoid dermatitis than retinyl esters although they are far less likely to cause retinoid dermatitis than retinoic acid.34 Other factors such concentration and delivery systems contribute to the tolerability profile of topical retinoids.35

| Cosmeceutical retinoids |

|---|

| Retinyl esters |

| Retinol |

| Retinaldehyde |

| Adapalene |

| Retinyl retinoate |

| Hydroxypinacolone retinoate |

| AHA-ret or AlphaRet® |

When retinol and retinaldehyde are applied to the skin, the majority is converted back to retinyl esters that serve as the storage form of vitamin A within the skin.36 Through a series of enzymatic conversions, retinyl esters are hydrolyzed to retinol, retinol is oxidized to retinaldehyde, and retinaldehyde is irreversibly oxidized to retinoic acid (Figure 1).2 Conversion of these molecules to retinoic acid is under tight control and occurs only as the cell needs it. This helps maintain relatively low levels of retinoic acid within the cell and minimizes irritation when precursor molecules are applied.36

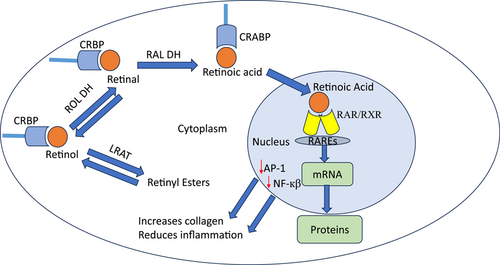

The biologic effects of all forms of vitamin A are dependent on their ability to bind to cytoplasmic and nuclear receptors (Figure 2).36-40 Retinol and retinaldehyde bind to cellular retinol-binding protein (CRBP).37 There are two isomers CRBP I and CRBP II. In contrast, retinoic acid binds to cellular retinoic acid binding protein (CRABP) that also has two isomers CRABP I and CRABP II. It is believed that CRABP II facilitates the translocation of retinoic acid into the nucleus where it binds to nuclear receptors. There are two families of nuclear receptors, retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs).38-40 There are three isoforms of both RARs and RXRs, α, β, and γ. In the epidermis, RARγ/RXRα is the heterodimer that binds retinoic acid to DNA retinoic acid response elements (RAREs).41 RAREs are found in the promoter region of target genes and promote mRNA and protein synthesis. Retinoids also have indirect effects that occur due to downregulation of transcription factors including AP-1 and NF-кB.42 Thus, retinoids prevent collagen breakdown by MMPs and mitigate the production of proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, retinoids upregulate the TGF-β pathway increasing collagen synthesis. This regulation of dermal matrix homeostasis is believed to be the mechanism whereby topical retinoids efface wrinkles.

5 RETINOL

Retinol is the most well studied precursor molecule and has been shown to have epidermal and dermal effects in skin (Table 2).3 Retinol is lipid soluble and penetrates the epidermis and upper levels of the dermis.40 Most commercially available retinol products contain 0.04%–1.0% although many products are not labeled accordingly.3 Although it might seem logical that higher concentrations of retinol should be more effective, a comparative study demonstrated that stabilized 0.1% retinol upregulated CRABP II more than a 0.2% prestige brand.48 This data underscores the importance of evaluating retinols on a product-by-product basis.

Early studies by Kang et al. demonstrated that topical 1.6% retinol under occlusion increased expression of CRABP II mRNA as did tretinoin 0.025%.43 Retinol treatment under occlusion also induced epidermal hyperplasia but was associated with less erythema and skin irritation compared to tretinoin. Application of retinol 0.1% cream to ex vivo skin explants demonstrated that retinol treatment induced CRABP II and HB-EGF gene expression and increased keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal thickness.44 In the same study, human volunteers applied the retinol 0.1% cream for 36 weeks and showed improvement in wrinkles under the eyes, fine lines, and skin tone evenness compared to placebo control. Li et al. demonstrated that application of a stabilized retinol 0.1% to human skin equivalents increased hyaluronic acid synthases (HAS) and HA accumulation in the epidermis compared to control.47

Studies have also demonstrated that retinol modulates components of the dermal extracellular matrix. Retinol 0.4% lotion applied three times a week for 24 weeks to forearm skin significantly increased glycosaminoglycan (GAG) expression and procollagen 1 immunostaining in intrinsically aged skin.45 Retinol 0.1% was compared to tretinoin 0.1% and vehicle when applied to forearm skin once a week under occlusion for 4 weeks.46 Epidermal thickness increased, collagen types 1 and 3 gene expression was upregulated, and increases in procollagen 1 and III protein expression was seen in the papillary dermis with both RA and ROL. It is important to note that retinols effects were approximately twofold lower than retinoic acid. Retinol 0.4% has also been shown to increase elastin fiber formation when added to cultured dermal fibroblasts and promote elastin fiber network as evidenced by Luna staining on biopsy in human skin explants.49 Thus, like retinoic acid, retinol's ability to modulate dermal extracellular matrix components like collagen, GAGs, and elastin play a major role in its antiaging benefits.3

Clinical studies have confirmed that retinol can improve the phenotype of photoaged skin. Pierard-Franchimont et al. conducted a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, controlled study (n = 120) comparing 0.04% retinol, 1% melibiose/4% lactose, and 0.04% retinol/1% melibiose/4% lactose using 1% salicylic acid as a comparator.50 All three test products caused significant improvement in skin elasticity as measured by cutometer and fine lines and wrinkles by image analysis of skin replicas. The authors concluded that all three test products were superior to 1% salicylic acid treatment. Using a higher concentration retinol, Tucker-Samaras et al. tested 0.1% stabilized retinol in an 8-week, randomized, vehicle-controlled, split-face study of 36 females with moderate photodamage.51 This study demonstrated that application of a 0.1% stabilized retinol cream caused statistically significant improvement in facial wrinkles, pigmentation, elasticity, firmness, and overall photodamage compared to vehicle control (p < 0.05). The test product was well tolerated with no erythema, scaliness, or edema. Long-term use of the same stabilized 0.1% retinol cream has also been studied in a 52-week, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study.52 The test retinol improved parameters of skin aging including cheek wrinkles, crow's feet, under-eye wrinkles, discrete pigmentation, mottled pigmentation, and overall skin tone with progressive improvement over the 52 weeks. As early as 12 weeks, retinol was significantly better than vehicle at improving overall photodamage and crow's feet (p < 0.05%), and from Week 24 to 52 the test retinol was significantly better than vehicle at improving all measured parameters of photoaging (p < 0.05%). Notable was a 44% improvement in crow's feet and an 84% improvement in pigmentation over baseline at the end of 52 weeks in the retinol-treated group. It was also noted that over half of the subjects in the retinol-treated group showed a 2+ grade improvement in many of the parameters of aging skin that were assessed. A limited number of biopsies were performed to see if the skin remained responsive to retinol throughout the duration of the study. The investigators found that retinol-treated photoaged skin showed an increased expression of type 1 procollagen at 52 weeks and an increase in Ki67 staining, an indicator of epidermal proliferation, through the end of the study. There was an increased expression of hyaluronan in both the dermis and epidermis throughout the study.52

Retinol has also been compared to topical tretinoin.53 In a comparative study, three strengths of retinol were evaluated against three strengths of tretinoin. It is generally thought that retinol is 10 times less potent than tretinoin. Accordingly, in this split-face study of 65 subjects with moderate to severe photodamage, tretinoin 0.025% was evaluated against sustained release retinol 0.25%, tretinoin 0.05% was tested against sustained release 0.5% retinol, and tretinoin 0.1% was tested against sustained release 1.0% retinol. After 12 weeks of applying retinol to one side of the face and tretinoin to the other, both products produced significant improvement from baseline in all efficacy parameters, including overall photodamage, fine lines and wrinkles, coarse lines, skin tone brightness, mottled pigmentation, pore size, and tactile roughness (p < 0.001 for all parameters). There was no significant difference in efficacy between the retinol and tretinoin-treated sides. Mean scores for erythema, dryness/scaling, and burning/stinging remained mild or below at Weeks 4, 8, and 12. At week 4 mean tolerability scores increased in all three treatment group test products. By week 12 there was no significant increase in any of the tolerability parameters for any test products.53

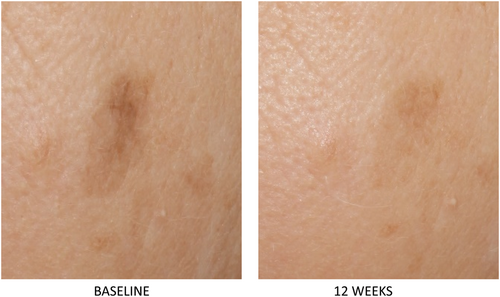

A unique 0.3% retinol serum was developed and tested to treat photoaged skin and hyperpigmentation across a diverse population.54 Retinol was combined with additional ingredients that were selected to enhance skin-lightening benefits and minimize skin irritation. Additional ingredients include Centella asiatica leaf extract to sooth, sodium hyaluronate to hydrate, niacinamide, and acetyl glucosamine to enhance skin lightening. Preclinical studies demonstrated that the test product upregulated expression of retinol-mediated genes including CRABPII, HBEGF, and HAS3.54 In a clinical study of 40 women skin types I–VI (30% Black, 8% Asian, 2% other, 60% Caucasian) the test serum produced statistically significant improvement in all graded parameters at week 12 compared to baseline including mottled hyperpigmentation, skin tone evenness, brightness, fine lines and wrinkles, pore size, tactile roughness (p < 0.05).54 (Figures 3 and 4) The serum was well tolerated with less than mild scores on average for redness, scaling, burning, stinging, dryness, tightness, and edema. Three patients discontinued treatment due to skin irritation. Subject self-assessment confirmed skin benefits and tolerability across all skin types.

6 RETINALDEHYDE

Retinaldehyde is a precursor molecule to RA that is popular in cosmeceuticals. It requires only one step to be converted to retinoic acid thus it is viewed as the strongest of the precursor molecules. Most commercially available products contain RAL at 0.05%–0.1% In a study designed to explore the biologic activity of retinaldehyde, subjects applied RAL 1.0%, 0.1%, and 0.05% in a cream vehicle to the forearm 4 days under occlusion.55 Induction of CRABP II mRNA expression and CRABP II protein was seen with all concentrations of RAL compared to vehicle control. There was no irritation seen in the RAL-treated sites. Induction of CRABP II was compared to other retinoids and was greatest with 0.05% RA followed by 0.05% RAL, 0.05% 9-cis RA, and 0.05% ROL in that order.55 Interestingly β-carotene at 0.5% did not increase CRABP II levels. Volunteers were treated for 1–3 months with 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.05% RAL. Topical RAL was found to increase epidermal thickness, keratin 14 immunoreactivity, and Ki67-positive cells in a dose-dependent manner. RAL 0.5% also increased expression of filaggrin, transglutaminase, and involucrin and increased the number of Ki67 cells in the basal layer threefold. Tolerability of different concentrations of RAL was evaluated in 229 patients with various inflammatory dermatoses including psoriasis, seborrhea, acne, atopic dermatitis, and in patients with melasma and photoaging (N = 41). The 1% RAL was tolerated by 69% of subjects with 31% of patients discontinuing treatment due to irritation. Tolerability of RAL 0.5% was slightly better while the 0.1% and 0.05% used mostly on the face was well tolerated even in patients with facial dermatitis.55

Clinical studies have confirmed the skin benefits of retinaldehyde. Creidi et al. compared retinaldehyde 0.05% with tretinoin 0.05% in a 44-week, vehicle-controlled study of 125 subjects.56 In this study, both retinaldehyde and tretinoin produced comparable and statistically significant reduction in wrinkles and skin roughness. Silicone replicas were also performed of the crow's feet area and optical profilometry confirmed these benefits in both RA and RAL treated groups. The retinaldehyde was well tolerated whereas tretinoin produced some skin irritation. Two concentrations of retinaldehyde 0.05% and 0.1% were tested in a 3-month, randomized, double-blind controlled trial.57 Wrinkles were assessed using the Antera 3D systems and transepidermal water loss, hydration, melanin index, skin brightness, and overall improvement were measured. Both concentrations caused significant improvement in all parameters except melanin index was improved only by the higher concentration. There was no difference otherwise between the two groups.57

7 RETINYL ESTERS

Despite their widespread use in cosmeceuticals, there is a paucity of data on retinyl esters. In an early randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study, 0.15% retinyl propionate was tested in 75 patients with mild to severe photodamage.58 At the end of the 24-week study, 60 subjects elected to continue for an additional 24 weeks. Subjects applied the test product or vehicle to the backs of the hands, forearms, and face. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in clinical assessment of photodamage even when patients were stratified as to the degree of photodamage. There was also no difference between the test product and vehicle control in photographic analysis, subject self-assessment, skin surface replicas and profilometry, and histologic evaluation. The authors suggest that a higher concentration of retinyl propionate should be tested.

Retinyl esters are often found in cosmeceuticals alongside retinol. Accordingly, a comparative study was conducted where patients were randomized to receive tretinoin 0.02% cream or a combination of topical tretinoin precursors 1.1% (TTP) once daily for 24 weeks.59 TTP 1.1% contained retinol, retinyl acetate, and retinyl palmitate. The patients applied the product once daily to moderate to severe facial photodamage. The treatment with TTP was associated with erythema six times less frequently than RA. Target gene expression assessed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction of biopsied tissue from TTP-treated areas showed induction of CRABP II mRNA confirming retinoic acid receptor signaling but no changes in procollagen I or MMP1/3/9 mRNA. TTP treatment significantly reduced MMP2 mRNA that encodes for type IV collagenase, and this was strongly correlated with improvement in fine wrinkles. The authors suggest that MMP2 may be a mediator of retinoid efficacy in photoaging.59

8 ADAPALENE

Adapalene was developed with the goal of creating a more stable, tolerable retinoid with receptor specificity for RARγ and RARβ.60 Adapalene 0.1% gel is now available over the counter in the United States, while the 0.3% gel is still available by prescription only. Adapalene has been studied extensively for treating acne while fewer studies have looked at its benefits for treating photoaged skin. Kang et al. conducted a two-center, randomized, vehicle-controlled, blinded, parallel-group study of 83 patients with actinic keratoses (AKs) and solar lentigines.61 After 9 months of treatment, both 0.1% and 0.3% adapalene significantly reduced the number of AKs by 0.5 ± 0.9 (mean ± SE) and 2.5 ± 0.9 while there was an increase of 1.5 ± 1.3. (p < 0.05) in vehicle-treated subjects. At 9 months, subjects treated with both concentrations of adapalene demonstrated lightening of solar lentigines of 57% and 59% respectively compared to only 36% in vehicle control (p < 0.05). Evaluation of photographs by blinded dermatologists demonstrated that after 9 months of adapalene there was clinical improvement in other parameters of photoaging including wrinkles.61

Although it remains available only by prescription, adapalene 0.3% gel shows promising results for treating photoaged skin in diverse ethnicities. In a 6 month, open-label study of 40 Latin American women, adapalene 0.3% gel was found to be effective for treating photoaged skin.62 There were significant improvements in clinical grading of wrinkles (p < 0.01) with a reduction in mean severity score of 40% in forehead wrinkles, 52% in periorbital wrinkles, and 29% in perioral wrinkles. Melanin, transepidermal water loss, and skin hydration were also improved. Histology showed a significant reduction in the elastosis band of 11.6% at 12 weeks and 15.1% at 24 weeks. Adapalene 0.3% gel was well tolerated overall, although three patients discontinued treatment early in the study due to irritation.

Adapalene 0.3% gel has been compared to tretinoin 0.05% cream for the treatment of photoaging.63 The study was an investigator-blinded, parallel-group, comparison study that was conducted in Brazil. Subjects were randomized 1:1 and followed for 24 weeks. Clinical evaluation of subjects at the end of 24 weeks showed no difference in the efficacy between the two products for improving photoaged skin. Global photoaging, periorbital wrinkles, ephelides/melanosis, forehead wrinkles, and AKs were improved equally in both groups compared to baseline. The investigators concluded that adapalene 0.3% gel showed noninferior efficacy compared to tretinoin 0.05% cream for treating photoaged skin with a similar tolerability profile.

9 NOVEL RETINOID MOLECULES

Retinyl retinoate is a unique molecule created with a condensing reaction between retinol to retinoic acid.64 This molecule is more active than retinol alone, has enhanced photostability, and is more gentle than retinoic acid. Retinyl retinoate has been shown to increase hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS 2) and hyaluronic acid in hairless mouse skin.65 It also caused less transepidermal water loss when compared to retinol, retinoic acid, and retinaldehyde which the authors suggest might explain why retinyl retinoate is less irritating.65

Retinyl retinoate was tested in 46 patients with mild to moderate photodamage and crow's feet.66 In the first study 0.06% retinyl retinoate was tested against placebo in 24 women and in the second study retinyl retinoate was tested against 0.075% retinol lotion in 22 women. The patients applied the products twice daily for 8 weeks and were evaluated every 4 weeks with investigator grading for photodamage, self-assessment, replica analysis, and visiometer. There was greater improvement in the retinyl retinoate-treated patients for overall photodamage and crow's feet compared to placebo and retinol 0.075% lotion.

Hydroxypinacolone retinoate (HPR) also called Granactive Retinoid®, is a retinoic acid ester making it unique among the retinoid family.67 HPR does not require conversion to retinoic acid and can interact directly with RA nuclear receptors. In a comparative study looking at 16 retinoid derivatives in commercialized products, HPR was found to be the most stable derivative.67 In vitro studies demonstrate that HPR can be combined with retinyl palmitate in an optimal weight ratio of 5:9.68 This combination added to human fibroblasts was found to synergistically increase expression of type IV collagen, CRABP I, and RARβ genes. In an 8-week clinical trial, 42 Chinese women used a serum with a combination of HPR and RP at the optimal weight ratio of 5:9. At the end of 8 weeks, subjects showed statistically significant improvement in skin wrinkles and elasticity with less adverse events compared to retinol alone at the same concentration.68 There is a lot more to learn about this unique retinoid, but preliminary results are promising.

AlphaRet® is a double-conjugated retinoid that combines a retinoid and lactic acid (AHA-ret).69 Through double hydrolysis, the ester bonds that hold the two molecules together are cleaved by naturally occurring enzymes in the skin. Skin benefits have been confirmed in a 12-week clinical trial of patients with mild to severe photoaging. In this split-faced study, subjects applied AHA-Ret to one side of the face and either 1% retinol or 0.025% retinoic acid to the other.69 Treatment with AHA-Ret showed progressive improvement in fine lines and wrinkles, dyschromia, erythema, skin tone, pore size, and global photoaging over 12 weeks of use. There was also significant improvement in skin hydration believed to be due to the presence of a lactic acid molecule. AHA-Ret was noninferior to tretinoin at 4 and 8 weeks in all categories and for fine line and wrinkles, erythema, skin tone, and dyschromia. There was less irritation in the AHA-Ret group compared to retinol or RA.69

10 GUIDELINES FOR CLINICAL USE

Although cosmetic retinoids are generally more tolerable than prescription retinoids, their side effect profile still limits their use. Retinoid dermatitis is generally seen in the first few weeks and is indicative of a process referred to as retinization of the skin.70 To mitigate this problem, users are instructed to apply topical retinoids sparingly every 2–3 days for the first several weeks and to apply a moisturizer either before and/or after application. The so-called “sandwich technique” of applying a topical retinoid between two layers of moisturizer has recently been popularized on social media. Despite their widespread use, these techniques for mitigating retinoid dermatitis are largely anecdotal. Draelos, et al. conducted a paired, double-blind study to determine if preconditioning the skin with a barrier-enhancing cosmetic moisturizer and continued use through retinoid therapy would help abate retinoid dermatitis.71 In this study patients applied a moisturizer containing niacinamide, panthenol, and tocopherol acetate to one side of the face and the same moisturizer without the vitamins to the other for 2 weeks before treatment was initiated with tretinoin 0.025% cream. Subjects then continued to use tretinoin 0.025% cream nightly followed by moisturizers for 8 weeks. The results showed that barrier function, as reflected by TEWL, was better in both phases of the study on the side treated with the vitamin-containing moisturizer. There was also significantly less dryness and peeling on the vitamin-containing side compared to vehicle control.71 Taking an approach such as this for patients who are initiating retinoids or retinoid intolerant might be helpful. Additionally, users are also instructed to apply cosmetic retinoids at bedtime to avoid photodegradation and not to use them during pregnancy and breastfeeding.71 Although studies have not confirmed negative effects on fetal development from topical retinoids, it is still prudent to avoid them during pregnancy and breastfeeding.72

11 CONCLUSION

Retinoids remain the gold standard for treating photoaged skin. While the benefits of tretinoin are well documented, having the option to purchase over-the-counter retinoids is appealing to consumers. We now have a plethora of cosmeceutical retinoids to offer to our patients who are looking for cosmetic solutions for skin rejuvenation. With so many choices, it is difficult for consumers and even dermatologists to navigate the marketplace and understand the differences between products. There are four key variables that determine retinoid efficacy and likely patient satisfaction. These include retinoid type, concentration, vehicle, and number and length of application. The efficacy of cosmeceutical retinoids continues to improve with the development of new molecules and novel formulation techniques to better stabilize and deliver retinoids to the skin. Dermatologists need to keep current on the science behind cosmeceutical retinoids so they can advise their patients on what works, what doesn't and what is worth the money.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author has nothing to report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Farris serves as a consultant/advisor to Alumier MD, Cerave, Figure 1 Beauty, La Roche Posay, Neutrogena, Pierre Fabre, Skinceuticals, Regimen MD.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this review article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.