High throughput FRET analysis of protein–protein interactions by slide-based imaging laser scanning cytometry

This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Robert Clegg, a pioneer and leading expert in FRET techniques.

Nikoletta Szalóki and Quang Minh Doan-Xuan are equal first authors.

György Vámosi and Zsolt Bacsó are equal senior authors.

Abstract

Laser scanning cytometry (LSC) is a slide-based technique combining advantages of flow and image cytometry: automated, high-throughput detection of optical signals with subcellular resolution. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a spectroscopic method often used for studying molecular interactions and molecular distances. FRET has been measured by various microscopic and flow cytometric techniques. We have developed a protocol for a commercial LSC instrument to measure FRET on a cell-by-cell or pixel-by-pixel basis on large cell populations, which adds a new modality to the use of LSC. As a reference sample for FRET, we used a fusion protein of a single donor and acceptor (ECFP-EYFP connected by a seven-amino acid linker) expressed in HeLa cells. The FRET efficiency of this sample was determined via acceptor photobleaching and used as a reference value for ratiometric FRET measurements. Using this standard allowed the precise determination of an important parameter (the alpha factor, characterizing the relative signal strengths from a single donor and acceptor molecule), which is indispensable for quantitative FRET calculations in real samples expressing donor and acceptor molecules at variable ratios. We worked out a protocol for the identification of adherent, healthy, double-positive cells based on light-loss and fluorescence parameters, and applied ratiometric FRET equations to calculate FRET efficiencies in a semi-automated fashion. To test our protocol, we measured the FRET efficiency between Fos-ECFP and Jun-EYFP transcription factors by LSC, as well as by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry, all yielding nearly identical results. Our procedure allows for accurate FRET measurements and can be applied to the fast screening of protein interactions. A pipeline exemplifying the gating and FRET analysis procedure using the CellProfiler software has been made accessible at our web site. © 2013 International Society for Advancement of Cytometry

(1)

(1)where R0 is the Förster radius, at which E = 0.5. Because of its sensitive distance dependence, FRET can be used as a molecular ruler to assess intra- or inter-molecular distances 4, molecular conformation or association state. FRET has several effects on the fluorescence parameters of the donor and the acceptor, which can be used to determine E in different ways 3, 5, 6. The fluorescence lifetime and quantum yield of the donor decreases resulting in a decrease of the donor intensity (donor quenching), whereas the intensity of the acceptor is enhanced (sensitized emission). E can also be determined by selectively bleaching the donor 7, 8 or the acceptor. In acceptor photobleaching, the enhancement of the donor intensity is measured after photodestruction of the acceptor dye 9, 10. The advantage of photobleaching methods is the simplicity of the experiment and data analysis. However, irreversible photobleaching precludes monitoring the time course of processes on the same cells. Bleaching requires time, which can lead to the motion of the sample compromising the spatial resolution. Reversible blinking of fluorescent proteins, especially of red variants such as mRFP1 and mCherry, is another source of complications in photobleaching experiments.

Ratiometric methods are faster and nondestructive 11, 12. They are based on the simultaneous detection of donor quenching and acceptor sensitized emission at multiple wavelengths. By using spectral and instrumental correction factors, pure donor and acceptor intensities (proportional to the expression levels) and FRET efficiencies can be derived on a cell-by-cell or pixel-by pixel basis by using flow cytometry or imaging microscopy. The flow cytometric version of the method provides excellent statistics over large cell populations 11, 13, 14, while microscopic imaging allows FRET analysis of adherent cells with sub-cellular resolution and in a repetitive manner in situ. A limitation of intensity based FRET methods is that they cannot resolve donor subpopulations characterized by different individual E values, e.g., those having or missing an acceptor pair. Thus, the measured apparent E value is an average over individual FRET efficiencies arising from different donors in the observation area (e.g., in a diffraction limited spot). In case only a fraction of donors is in complex with an acceptor, the gained FRET efficiency can be considered as a lower limit of the real E value. To resolve donor subpopulations characterized by different E values, fluorescence lifetime measurements 15-17 or single molecule conditions are needed 18, 19.

Cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins (ECFP and EYFP), as well as green and red fluorescent proteins (EGFP and mRFP1 or mCherry), are often used as donor–acceptor pairs because of their substantial spectral overlap and their consequently high R0 20-22. Earlier, we used EGFP- and mRFP1 or mCherry to map interactions between FP-tagged nuclear or plasma membrane proteins using ratiometric FRET measurements by flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) 23, 24. A pivotal problem of ratiometric FRET methods is the determination of the so-called α factor, which is a “photon exchange rate” comparing signal intensities in the donor and transfer detection channels arising from equal amounts of excited donor and acceptor dyes. To assess α, fusion proteins of donor and acceptor dyes can be used, which are expressed in a single polypeptide at one-to-one ratio 23, 24.

Fos and Jun proteins are members of the bZIP family of transcription factors containing a highly conserved basic region involved in DNA binding and a heptad repeat of leucine residues. They function as homo- or hetero-dimers that bind to AP-1 (activator protein-1) regulatory elements in the promoter and enhancer regions of numerous mammalian genes 25. Because of their propensity to form stable heterodimers via a leucine-zipper, Fos and Jun are often used as positive controls in dimerization studies. Earlier, we demonstrated their stable heterodimer formation by FCCS 26 and FRET 23 in live cells, and described the C-terminal conformation of the complex using a Fos-GFP + Jun-mRFP1 pair.

The laser scanning cytometer (LSC) is a microscope-based cytofluorometer, which has attributes of both flow cytometry and microscopy 27. LSC expands the capabilities of flow cytometry to the analysis of solid tissues and adherent cells and significantly improves the statistic power of microscopy methods. Optical signals from fluorophore or dye labeled individual cells lodged on a microscope slide are measured at multiple wavelengths 28, 29. The specimen carrier is mounted on a computer-controlled, motor-driven stepper stage allowing automated analysis of thousands of individual cells in a short duration. Detected signals comprise forward light scattering, light-loss, and fluorescence intensities. Contouring by one or a combination of these signals allows segmentation of the image, e.g., discrimination of cells or cellular organelles. From the primary signals, the total fluorescence, highest pixel intensity, or total area of a cell or a sub-cellular structure can be determined, and arithmetic calculations among parameters can be carried out. LSC is capable of relocalizing cells allowing, e.g., monitoring the same cells before and after a treatment or following the time course of processes. LSC has been found useful to analyze various cellular processes ranging from enzyme reaction kinetics to apoptotic DNA damage 30-33.

The phenomenon of FRET donor de-quenching has been used in some applications. Enhancement of donor emission after photobleaching the acceptor moiety of FRET-based tandem dyes has been demonstrated 34. Cleavage by caspase of a CFP-YFP-labeled FRET sensor has been detected in an apoptosis assay 35. However, the FRET efficiency has not been assessed in any of these applications, and no quantitative FRET measurements have been carried out to investigate molecular associations; the focus of the aforementioned studies was different.

Here, we demonstrate that a commercially available standard LSC equipped with 405-, 488-, and 633-nm laser lines can be used for the identification of adherent, ECFP-EYFP double-positive HeLa cells. It is shown that ECFP and EYFP fluorescence can be detected with sufficiently high sensitivity and accuracy, and application of a reference sample with known FRET efficiency makes reliable FRET measurements on other samples possible. We compare FRET results obtained with a CLSM having optimal excitation wavelengths for the excitation of ECFP and EYFP (458 and 514 nm) with results gained from the LSC and a flow cytometer, both having suboptimal excitation wavelengths (405 and 488 nm). We introduce a novel numerical method to calculate the so-called α factor and the FRET efficiency from the same set of equations simultaneously. By using an ECFP-EYFP fusion protein as a standard, FRET efficiencies measured between Fos and Jun proteins using the different instruments are nearly identical. We define the methodology for semi-automated FRET measurements uniting the high throughput of flow cytometric FRET with the capability of subcellular resolution and cell back-tracking in a single instrument. Our method can facilitate screening of protein interactions by using FRET-based LSC assays.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Plasmid Construction, Transfection, and Fluorescence Labeling

Cell culture conditions, transfection, and fluorescence labeling are described in the Supporting Information. Shortly, FRET experiments were carried out using HeLa cells transfected with fluorescent proteins. Construction of the expression vectors pSV-c-Fos-ECFP, pSV-c-Jun-EYFP, and the positive control, pSV-ECFP-EYFP (coding for the fusion of the two fluorescent proteins connected by a RNPPVAT linker) is described elsewhere 26. pSV-Fos215-ECFP is a truncated version of full-length Fos-ECFP, where the last 164 amino acids have been deleted 23. Cells co-transfected with ECFP and EYFP plasmids were used as a negative control for FRET. Cells transfected with ECFP or EYFP alone were used for the determination of spectral cross-talk of the dyes between detection channels. For measurements with LSC and confocal microscopy, cells were plated in μ-Slide 8-well Ibidi chambered coverslip (Ibidi GmbH, Planegg/Martinsried, Germany). Membrane proteins were stained with Cy5 succinimidyl ester to define cell contours for segmentation of LSC data.

Laser Scanning Cytometric FRET

For slide-based scanning, an iCys Research Imaging Cytometer (CompuCyte Corporation, Westwood, MA) was used. The instrument is based on an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope equipped with three lasers, photodiodes (detecting light loss and scatter) and four photomultiplier tubes (PMTs). A 405-nm solid state laser, a 488-nm Argon laser, and a 633-nm HeNe laser were alternatively operated in multitrack mode to excite ECFP, EYFP, and Cy5, respectively. Laser beams scanned the sample point by point. The autofocus utility determined the inclination of the cover slip by triangulation (based on reflection of the 488-nm laser). During the scan, a fixed offset from the bottom of the cover slip was applied, which placed the focus to the middle plane of cells. User-defined areas on the specimen having optimal cell density were marked as regions of interest (ROIs) and scanned in an automated process. Each ROI was automatically divided into smaller areas called scan fields by the software. Each scan field (1024 × 768 pixels) was scanned by a focused laser beam via an oscillating mirror in the y direction and by the motorized stage in the x direction with a step size of 0.25 μm. The arising fluorescence signals were collected via a 40× (NA 0.75) objective, whereas transmitted light was captured by the light loss detector. Laser intensities at the objective were 151 μW for the 405-nm and 27 μW for the 488-nm lines. Donor and transfer signals with an excitation at 405 nm were collected through 460–500 and 520–580 nm band-pass filters by separate PMTs; the acceptor was excited at 488 nm and detected at 520–580 nm by the same PMT as the transfer signal; Cy5 fluorescence was excited at 633 nm and detected through a 650-nm long-pass filter. Raw scanned images were processed post-acquisition by the CellProfiler software, in which cellular events were defined, and pixel-by-pixel FRET calculations were carried out according to equations described in the “Data Analysis” section. FRET efficiencies were also calculated on a cell-by-cell basis from the mean cellular intensities gained from the ImageProfiler software by using Microsoft Excel for n ∼ 500 cells for each sample. Photostability of the dyes was checked by a time lapse experiment where the sample was scanned seven times. The extent of bleaching between two consecutive scans was 1% and 2.8% for ECFP and EYFP (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

Flow Cytometric FRET

Flow cytometric FRET measurements were carried out on a FACSAria III instrument (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Forward and side scattering were used to gate out debris and apoptotic cells. Donor and transfer signals were excited by a 405-nm solid state laser and detected between 430–470 and 515–545 nm, whereas the acceptor signal was excited by a 488-nm solid state laser and measured between 515 and 545 nm. Because of the spatial separation between the laser foci, fluorescence signals excited by the two lasers were detected with a time delay minimizing spectral crosstalk. For FRET calculations from flow cytometric data, the Reflex software developed at our institute was used 36. FRET efficiencies were presented as mean values of ∼10,000 double positive cells.

Collection of Ratiometric FRET Data by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

FRET measurements were performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 63× Plan Apochromat oil immersion objective (NA 1.4). The donor and transfer signals were excited by the 458-nm line of an Argon ion laser and detected simultaneously between 475–525 nm and 530–600 nm; the acceptor signal was excited at 514 nm and detected between 530 and 600 nm. The intensities of the 458-nm and 514-nm lines at the objective were 4.3 and 2.3 μW, respectively. The “Multi Track” option of the data acquisition software was used switching laser illumination line by line to minimize spectral crosstalk between the channels. Pixel time was 2.56 μs, and each line of the image was scanned four times and then averaged to reduce noise. The pinhole was set to 200 μm corresponding to an optical slice thickness of 1 μm. Images were collected from the middle plane of cells. The LSM data acquisition software was used to select ROIs including cells and to calculate the mean pixel intensities for each selected cell. FRET calculations with the mean intensities were performed with Microsoft Excel from n ∼ 100–150 cells per sample. Average background intensities were determined from nontransfected cells. For pixel-by-pixel FRET calculations, the RiFRET plugin of the ImageJ software 37 was applied. Photobleaching was checked in a time lapse experiment. The intensity of ECFP and EYFP decreased by 0.1% and 0.6% between consecutive images.

Acceptor Photobleaching FRET on CLSM

Acceptor photobleaching FRET measurements were carried out on the Fos-Jun samples and the positive and negative controls with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). FRET efficiency results with the positive control (ECFP-EYFP fusion protein with a RNPPVAT-linker) were used as a reference for ratiometric FRET measurements with the different instruments. ECFP was excited by the 458-nm line of an Ar ion laser and detected between 465 and 510 nm; EYFP was excited at 514 nm and detected between 535 and 590 nm. First, images of the donor and acceptor distributions were taken. Then, acceptor dyes were bleached by repetitive scans with the 514-nm laser at maximal laser power. After photobleaching, a donor image was recorded again. The LSM data acquisition software was used to define ROIs and calculate the mean cellular fluorescence intensities in each channel. Mean cellular FRET efficiencies from the above mentioned intensities using formulas described in the Supporting Information were calculated in Microsoft Excel from n > 20 cells. In the calculations, corrections for incomplete acceptor bleaching, unwanted donor bleaching, crosstalk of acceptor, and acceptor photoproduct into the donor channel were taken into account 10. For details, see Supporting Information.

Data Analysis

Ratiometric Determination of FRET Efficiency

(2)

(2) (3 and 4)

(3 and 4) (5 and 6)

(5 and 6) vs.

vs.

for S1) were fitted with Deming's method 39 in Graphpad. The term

for S1) were fitted with Deming's method 39 in Graphpad. The term

is a ratio of the extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at the wavelengths used for exciting the donor and the acceptor. For the FACSAria and the LSC:

is a ratio of the extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at the wavelengths used for exciting the donor and the acceptor. For the FACSAria and the LSC:

(7)

(7) (8)

(8) was negligible for the CLSM. The factor α, which is an “exchange rate” between donor and acceptor fluorescence, relates the I2 signal arising from a given number of excited EYFP molecules to the I1 signal from the same amount of excited ECFP molecules is defined by the following equation:

was negligible for the CLSM. The factor α, which is an “exchange rate” between donor and acceptor fluorescence, relates the I2 signal arising from a given number of excited EYFP molecules to the I1 signal from the same amount of excited ECFP molecules is defined by the following equation:

(9)

(9) and

and

are the detection efficiencies (including emission filter transmissions, detector sensitivities, and amplifications) of ECFP and EYFP fluorescence emission in channels 1 and 2, respectively. The value of α can be determined from two samples expressing known amounts of ECFP or EYFP as:

are the detection efficiencies (including emission filter transmissions, detector sensitivities, and amplifications) of ECFP and EYFP fluorescence emission in channels 1 and 2, respectively. The value of α can be determined from two samples expressing known amounts of ECFP or EYFP as:

(10)

(10) and

and

are the fluorescence intensities of ECFP and EYFP directly excited at the donor excitation wavelength (405 for the FACSAria and the LSC and 458 nm for the confocal microscope),

are the fluorescence intensities of ECFP and EYFP directly excited at the donor excitation wavelength (405 for the FACSAria and the LSC and 458 nm for the confocal microscope),

is the ratio of ECFP and EYFP fluorophores expressed by the samples, and

is the ratio of ECFP and EYFP fluorophores expressed by the samples, and

is the ratio of their extinction coefficients at the donor excitation wavelength. For the FACSAria and the LSC:

is the ratio of their extinction coefficients at the donor excitation wavelength. For the FACSAria and the LSC:

(11)

(11) (12)

(12) (13)

(13) (14)

(14) (15)

(15) (16)

(16) (17)

(17) (18)

(18)Equation 2 and those describing E, ID, IA, and α are considerably simplified for the LSC and the confocal microscope (see Supporting Information) because of the negligible values of S4 (LSC) or S3 and

(confocal).

(confocal).

Results

Detection of Cells by Automatic Segmentation, Gating of Cellular Events, and FRET Analysis

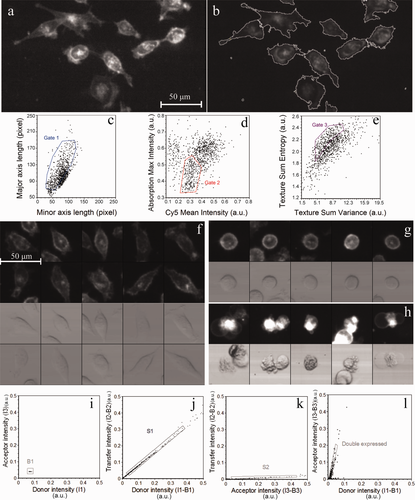

Raw images captured by LSC were analyzed with CellProfiler, an open-source software developed for high-throughput analysis of imaging cytometry data 40. CellProfiler features auto-segmentation and declumping modules using Otsu's method 41. The Cy5 signal was used primarily to detect cellular events (Fig. 1a). Identified events were marked with contour lines surrounding the event (Fig. 1b). Cellular parameters within the contours: fluorescence intensity profiles, area, perimeter, circularity, and location parameters of the events were generated and displayed by the software. Events underwent a multistep gating procedure. First, cells having a clear difference between the lengths of the major and minor axes, assumedly being adherent and having long filopodia, were selected (Figs. 1c and 1f). Floating detached cells obviously featured rounded shape with equal axes (Figs. 1c and 1g). Cells having high absorption signals were generally necrotic or apoptotic and were excluded from FRET analysis. These cells usually had high mean Cy5 intensities also because of their highly permeable membrane, and possessed a more granular texture (Figs. 1d, 1e, and 1h). Cellular texture parameters “sum entropy” and “sum variance” were computed by a built-in module of CellProfiler. Sum entropy is a measure of randomness within an image, whereas variance increases as the variability of pixel intensity of an image is increased 42.

From gated cells of dot plots, a gallery of 100–150 randomly chosen cells was displayed. Visual observation confirmed that the gating strategy outlined above sufficiently discriminated between attached healthy and detached dead or dying cells (Figs. 1f–1h).

Background determination for autofluorescence correction was done on Cy5-labeled nontransfected cells (Fig. 1i). Dot plots of background-corrected mean pixel intensities I2 vs. I1 (Fig. 1j) or I3 vs. I1 intensities from single ECFP-transfected cells were plotted to determine the S1 and S3 correction factors as the slopes of these graphs. Similarly, I2 vs. I3 signals from single EYFP-transfected cells were used to determine S2 (Fig. 1k). From double-labeled samples, cells expressing both donor and acceptor were selected for FRET evaluation (Fig. 1l). FRET efficiencies on a pixel-by-pixel or cell-by-cell basis were calculated using CellProfiler and Microsoft Excel, respectively, according to Eq. (S2) in the Supporting Information.

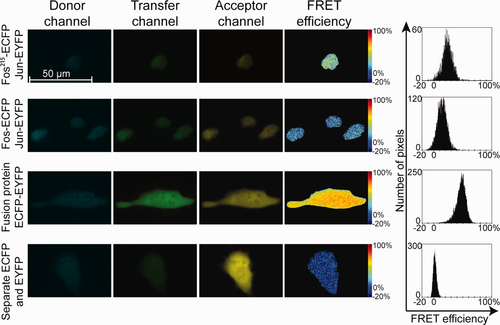

Ratiometric and Acceptor Photobleaching FRET Results Obtained by Confocal Microscopy

Confocal microscopic FRET measurements by the ratiometric 22, 23 and acceptor photobleaching 10, 43, 44 techniques are well established. We used these techniques to determine FRET on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. Results of cell-by-cell measurements for the positive and negative controls (ECFP-EYFP fusion, ECFP, and EYFP expressed as separate proteins) and for the full length and truncated Fos-Jun complexes are shown in Table 1. We used the acceptor bleaching FRET results as reference for the ratiometric values. The extent of heterodimer formation by Fos and Jun depends on the absolute concentrations as well as the relative amounts of these proteins: with increasing acceptor-to-donor ratio the FRET efficiency increases 23. Therefore, for comparing FRET efficiencies gained with the two methods, we selected those cells for which this ratio was higher than 1 and the E vs. acceptor-to-donor ratio curve had a plateau (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Full length Fos has a longer C terminal domain than Jun, whereas the C terminal domain of the truncated Fos215 after the dimerization domain is similar in length to that of Jun. Therefore, the FRET efficiency between Fos215-Jun is significantly higher than for the full length Fos-Jun pair 23.

Ratiometric E (mean ± SD) with

|

Ratiometric E (mean ± SD) with

|

Acceptor photobleaching E (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP-EYFP (positive control) | 47.3 ± 3% | 37.9 ± 2.5% | 48.5 ± 1.8% |

| ECFP + EYFP (negative control) | 0.9 ± 1.2% | 0.6 ± 0.8% | 1.0 ± 1.5% |

| Fos215-ECFP + Jun-EYFP | 22.0 ± 1.9% | 16.0 ± 1.1% | 21.2 ± 3.3% |

| Fos-ECFP + Jun-EYFP | 7.9 ± 2.5% | 5.5 ± 1.7% | 8.0 ± 3.6% |

-

Ratiometric calculations were carried out assuming

= 26,000 M−1 cm−1 (left column) or 32,500 M−1 cm−1 (center column).

= 26,000 M−1 cm−1 (left column) or 32,500 M−1 cm−1 (center column).

The laser lines of the microscope (458 and 514 nm) are optimal for the excitation of ECFP and EYFP, yielding an excellent signal-to-noise ratio. For calculating FRET efficiencies, knowledge of the α factor is indispensable. The excitability of EYFP at 458 nm is sufficiently high (

is 8.2% of the peak extinction) to allow for the reliable determination of the S2 [Eq. (5)],

is 8.2% of the peak extinction) to allow for the reliable determination of the S2 [Eq. (5)],

[Eq. 12], and, via Eqs. 13 and 14, the α factors, making reliable FRET calculations possible. Two ratiometric FRET efficiency values are reported for each sample corresponding to two different values of the

[Eq. 12], and, via Eqs. 13 and 14, the α factors, making reliable FRET calculations possible. Two ratiometric FRET efficiency values are reported for each sample corresponding to two different values of the

absorption ratio. The reason for this uncertainty is the following. E is a monotonously decreasing function of the α factor [Eq. 15], which itself depends linearly on

absorption ratio. The reason for this uncertainty is the following. E is a monotonously decreasing function of the α factor [Eq. 15], which itself depends linearly on

, the ratio of the extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at the donor excitation wavelength, 458 nm [Eqs. 12 and 13]. Because there is ambiguity regarding the peak extinction coefficient of ECFP in the literature (

, the ratio of the extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at the donor excitation wavelength, 458 nm [Eqs. 12 and 13]. Because there is ambiguity regarding the peak extinction coefficient of ECFP in the literature (

= 26,000 M−1 cm−1 in 45; 28,750 in 46; 32,500 in 47),

= 26,000 M−1 cm−1 in 45; 28,750 in 46; 32,500 in 47),

cannot be determined unequivocally. The extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at 458 nm (Supporting Information Table S1) were estimated as the product of the peak extinction coefficient of the corresponding dye and the extinction at 458 nm relative to the peak. The relative percentages were assessed from the excitation spectra of ECFP (measured in house on a Jobin Yvon Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorimeter) and EYFP (using the BD Fluorescence Spectrum Viewer on the Becton Dickinson homepage). As shown in Table 1, the FRET efficiency values determined by the ratiometric method are in good agreement with the acceptor photobleaching FRET results. We considered the FRET efficiencies from acceptor photobleaching experiments as reference values for the other techniques.

cannot be determined unequivocally. The extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at 458 nm (Supporting Information Table S1) were estimated as the product of the peak extinction coefficient of the corresponding dye and the extinction at 458 nm relative to the peak. The relative percentages were assessed from the excitation spectra of ECFP (measured in house on a Jobin Yvon Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorimeter) and EYFP (using the BD Fluorescence Spectrum Viewer on the Becton Dickinson homepage). As shown in Table 1, the FRET efficiency values determined by the ratiometric method are in good agreement with the acceptor photobleaching FRET results. We considered the FRET efficiencies from acceptor photobleaching experiments as reference values for the other techniques.

Ratiometric FRET Results Obtained by LSC and Flow Cytometry

To measure ratiometric FRET with high throughput, we used LSC and flow cytometry. As explained above, the major difficulty in ratiometric FRET calculations is the determination of the α factor [Eq. 13], for which knowledge of the

and the S2 factors are required. In the case of the LSC and the flow cytometer, the 405 and 488 nm laser lines were used to excite ECFP and EYFP, respectively.

and the S2 factors are required. In the case of the LSC and the flow cytometer, the 405 and 488 nm laser lines were used to excite ECFP and EYFP, respectively.

depends linearly on

depends linearly on

, which is less than 2% of the peak extinction value (Supporting Information Table S1), and its exact value is not known. In addition, S2 is determined from

, which is less than 2% of the peak extinction value (Supporting Information Table S1), and its exact value is not known. In addition, S2 is determined from

, the acceptor fluorescence excited at 405 nm, which is very low due to the low extinction coefficient. Therefore, the value of both of these parameters (and consequently α), carries large error, and leads to a large uncertainty of E values. A further source of error is the uncertainty in

, the acceptor fluorescence excited at 405 nm, which is very low due to the low extinction coefficient. Therefore, the value of both of these parameters (and consequently α), carries large error, and leads to a large uncertainty of E values. A further source of error is the uncertainty in

[Eq. 7], which also depends on

[Eq. 7], which also depends on

. When substituting the possible extreme values of

. When substituting the possible extreme values of

and

and

(Supporting Information Table S1) into the expressions of

(Supporting Information Table S1) into the expressions of

and

and

, the resulting ranges of E values for the positive control are very broad (Table 2). The uncertainty of the extinction coefficients involved in the equations impairs quantitative FRET calculations. To get around this problem, we used the FRET efficiency of the positive control from acceptor photobleaching (E = 48.5%) as a standard. The utility of this sample as a standard is that it has an intramolecular FRET process; thus, the FRET efficiency is independent of the expression level of the ECFP-EYFP protein. In the FRET calculations of LSC, flow cytometric and confocal microscopic data according to Eq. 15 the value of α was set to yield E = 48.5% for the population average. This α was used in subsequent FRET calculations of the Fos-Jun samples and the negative control. By using this approach, FRET efficiencies derived from the different instruments show excellent agreement (Table 3).

, the resulting ranges of E values for the positive control are very broad (Table 2). The uncertainty of the extinction coefficients involved in the equations impairs quantitative FRET calculations. To get around this problem, we used the FRET efficiency of the positive control from acceptor photobleaching (E = 48.5%) as a standard. The utility of this sample as a standard is that it has an intramolecular FRET process; thus, the FRET efficiency is independent of the expression level of the ECFP-EYFP protein. In the FRET calculations of LSC, flow cytometric and confocal microscopic data according to Eq. 15 the value of α was set to yield E = 48.5% for the population average. This α was used in subsequent FRET calculations of the Fos-Jun samples and the negative control. By using this approach, FRET efficiencies derived from the different instruments show excellent agreement (Table 3).

|

|

Range of average E for positive control (ECFP-EYFP) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser scanning cytometer | 42.6–9.5 | 0.0029–0.0066 | 44%–224% |

| Flow cytometer | 31%–135% |

| Sample | Confocal laser scanning microscope | Laser scanning cytometer | Flow cytometer |

|---|---|---|---|

| E (mean ± SD) | E (mean ± SD) | E (mean ± SD) | |

| ECFP-EYFP (positive control) | 48.5% | 48.5% | 48.5% |

| ECFP + EYFP (negative control) | 0.84 ± 0.9% | 0.65 ± 1.6% | 1.8 ± 1% |

| Fos215-ECFP + Jun-EYFP | 21.1 ± 1.3% | 23.6 ± 2.8% | 22.1 ± 3.7% |

| Fos-ECFP + Jun-EYFP | 8.3 ± 1.9% | 8.6 ± 2.9% | 10.2 ± 3.6% |

- E values were calculated only for cells with an acceptor-to-donor ratio larger than 1.

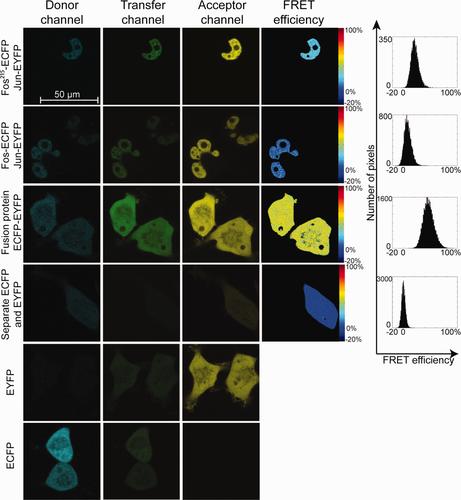

In addition to being able to measure a large number of cells, LSC has the advantage that it can also provide a map of subcellular FRET distribution. Thus, protein–protein interactions can be localized to specific cellular compartments. Such FRET efficiency maps of Fos-Jun interactions are shown (Fig. 2) along with similar data gained by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3). Fos-Jun dimers show nuclear localization, whereas the positive and negative controls are present in the whole cell. Pixel-by-pixel FRET efficiencies from the two instruments are nearly identical and show no significant spatial variation, similar to earlier results on Fos and Jun pairs 23. The advantage of confocal FRET images is their higher optical resolution (limit of resolution: r∼230 nm) and better signal-to-noise ratio, whereas LSC provides higher throughput with somewhat lower resolution (r∼420 nm).

A pipeline exemplifying the gating and FRET analysis procedure using the CellProfiler software has been made accessible at our web site (http://biophys.med.unideb.hu/en/node/227).

Discussion

FRET has a renaissance of biomedical applications, where its capacity to indicate molecular proximity relations is used. A major field of application is the screening of protein–protein interactions, which is important in many areas of biological research such as the study of signaling pathways or drug discovery. Recently, high throughput assays applying microscopic techniques with TIRF illumination to detect membrane protein interactions 48, or interactions between cells attached to a micropatterned surface with a “prey” protein 49 have been reported. FRET measured by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy has been applied to quantify posttranslational modifications in live cells 50 in a high throughput fashion. Here, we worked out a simple procedure to collect and analyze FRET data in a semiautomated fashion by using a commercially available laser scanning cytometer with a typical three-laser setup and open-source software. Raw images collected with the own software of the LSC were processed with the Cell Profiler open source image analysis program according to a custom protocol developed by us. In this procedure adherent, healthy cells expressing the protein of interest in sufficiently high amounts were selected and the cell-by-cell fluorescence intensities necessary for FRET analysis were calculated. Actual FRET calculations can be performed in any spreadsheet program using the classic ratiometric FRET equations. The throughput of FRET data acquisition by LSC (60 cells/min) was between that of confocal microscopy (1 cell/min) and flow cytometry (50,000 cells/min). The total data acquisition time for a complete FRET experiment by LSM with FRET samples and controls (50 cells/sample) took 6 h and the data analysis 4 h. For LSC, acquisition (3000 cells/sample) took 4 h, and did not require the presence of the operator, whereas analysis required 0.5 h/sample. FACS data acquisition and analysis took 2 h and 1 h, respectively.

ECFP and EYFP are among the most frequently used FRET reporters thanks to the ease at which they can be expressed as fusion proteins, and their significant spectral overlap resulting in a large Förster distance (4.92 ± 0.1 nm 20). In ratiometric FRET calculations, a pivotal element of the analysis is the determination of the α factor, which relates the signals arising from equal amounts of excited donor and acceptor molecules to each other. When calculating α, the donor and acceptor fluorescence intensities must be normalized by the number of molecules and by the efficiency of excitation. It is practical to use donor–acceptor fusion proteins, in which the donor and acceptor dyes are present at a 1:1 ratio. Normalization by the excitation efficiency is usually achieved by applying the same laser line to excite the donor and the acceptor, and division of the resulting fluorescence intensities by the ratio of the extinction coefficients of the two dyes at this wavelength (

). For the ECFP-EYFP pair, the 458 nm line is optimal for exciting ECFP, and sufficient to excite EYFP (Supporting Information Table S1). Because not all instruments have the optimal wavelengths for all possible dye pairs, it may be necessary to measure a reference sample at its optimal excitation wavelengths on another instrument. Its E value may then serve as a standard. The 458 and 514 lines are not available in the LSC and the BD FACSAria flow cytometer used in our study. The 405 nm line is suitable for exciting ECFP (the extinction coefficient is 55.1% of the maximum). On the other hand, the extinction of EYFP at this wavelength is very low; thus, α cannot be defined precisely. As a reference sample, we used an ECFP-EYFP fusion protein with a high E, which can be measured reproducibly, and is independent of the expression level. We demonstrated that using a FRET standard with predetermined FRET efficiency makes the determination of the α factor and reliable FRET measurements possible when using the 405 and 488 nm lasers. This was confirmed by the good agreement between results gained by acceptor photobleaching and ratiometric FRET techniques with the different instruments. By the application of the FRET standard, the FRET efficiency differences between the full-length Fos-ECFP + Jun-EYFP and the truncated Fos215-ECFP + Jun-EYFP protein pairs could clearly and reproducibly be resolved with all three methods. We also carried out pixel-by-pixel FRET analysis of LSC and confocal microscopic images, which yielded identical FRET distributions with each other and with the results of cell-by-cell analysis. This gives evidence that the sensitivity of LSC is sufficient for subcellular FRET analysis as well.

). For the ECFP-EYFP pair, the 458 nm line is optimal for exciting ECFP, and sufficient to excite EYFP (Supporting Information Table S1). Because not all instruments have the optimal wavelengths for all possible dye pairs, it may be necessary to measure a reference sample at its optimal excitation wavelengths on another instrument. Its E value may then serve as a standard. The 458 and 514 lines are not available in the LSC and the BD FACSAria flow cytometer used in our study. The 405 nm line is suitable for exciting ECFP (the extinction coefficient is 55.1% of the maximum). On the other hand, the extinction of EYFP at this wavelength is very low; thus, α cannot be defined precisely. As a reference sample, we used an ECFP-EYFP fusion protein with a high E, which can be measured reproducibly, and is independent of the expression level. We demonstrated that using a FRET standard with predetermined FRET efficiency makes the determination of the α factor and reliable FRET measurements possible when using the 405 and 488 nm lasers. This was confirmed by the good agreement between results gained by acceptor photobleaching and ratiometric FRET techniques with the different instruments. By the application of the FRET standard, the FRET efficiency differences between the full-length Fos-ECFP + Jun-EYFP and the truncated Fos215-ECFP + Jun-EYFP protein pairs could clearly and reproducibly be resolved with all three methods. We also carried out pixel-by-pixel FRET analysis of LSC and confocal microscopic images, which yielded identical FRET distributions with each other and with the results of cell-by-cell analysis. This gives evidence that the sensitivity of LSC is sufficient for subcellular FRET analysis as well.

The interpretation of the measured apparent FRET efficiencies is complicated by the existence of multiple photophysical states of the dyes, the unknown relative orientation of the transition dipoles of the dyes 51 and the variable extent of association between the donor- and acceptor-labeled molecules. ECFP and EYFP are characterized by at least two lifetimes each, and EYFP may be in a nonabsorbing dark state, which does not function as a FRET acceptor. Therefore, three lifetimes were discerned for an ECFP-EYFP fusion protein indicating that different donor–acceptor configurations were present characterized by distinct FRET efficiencies 52. Thus, apparent FRET efficiencies by intensity based FRET (including acceptor bleaching and ratiometric methods) are averages of real FRET efficiencies of the different species. In the case of intermolecular FRET, incomplete association of donor- and acceptor-labeled molecules results in a decreased apparent FRET efficiency. Titration of the acceptor-to-donor ratio 23 showed that at high A-to-D ratios the apparent E reached a saturation value (see Supporting Information), which can be regarded as the value characterizing the fully associated state. Thus, useful comparisons can be made between different conformations of complexes or different association states of donor- and acceptor-labeled molecules using ratiometric measurements.

Our data exemplify that FRET can be used as an additional modality in the versatile, high throughput analysis of cells by LSC. Such analyses could yield important information on molecular interactions not available by methods previously used in LSC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Dániel Beyer and György Vereb for comparing their acceptor photobleaching FRET data with ours and Attila Forgács for calculating confocal microscopic pixel-by-pixel FRET histograms.