“I don't think I took her fears seriously”: Exploring the experiences of family members of individuals at-risk of developing psychosis over 12 months

Abstract

Individuals with an at-risk mental state (ARMS) of psychosis experience high levels of distress, anxiety, low mood, and suicidal ideation. Families of ARMS individuals provide significant support but are often neglected by services. This study is the first of its kind to use a novel longitudinal qualitative methodology to directly compare family/carers' earlier experiences supporting ARMS individuals to 12 months later. This provides a more ecologically valid insight into how perceptions change over time and how family/carers adapt. Semistructured interviews were conducted with 10 family/carers at two points within a 12-month period. This study was embedded within a randomized control trial, the Individual and Family Cognitive Behavioural Therapy trial. Interview transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis, with a focus on how experiences and reactions for family/carers changed over time. Over 12 months, four factors were important for family/carers to facilitate their caring role. These were summarized in the thematic map (LACE model): Looking after your own well-being; Accessing additional support from family intervention; Communicating openly with the individual; and Engaging with services for the individual. All four aspects of the model were important in improving family communication, meeting family/carers' unmet needs, and helping them to feel more confident and less isolated in their carer role. Novel implications suggest that when feasible, services should involve family/carers of ARMS individuals in sessions and explore family/carer support strategies in managing their own distress. The most significant insight was the need to develop family/carer resources to educate, normalize, and validate their own experiences.

Key Practitioner Message

- Exploring coping strategies with family/carers to manage their worries, anxiety, and distress can help them to prioritize their own health and well-being.

- Psychoeducation and normalizing family/carers' experiences can help them to feel validated and reduce their worry.

- Facilitating open communication between the individual and family/carer can positively impact on their relationship.

- Early engagement between services and at-risk individuals can be validated and help families to feel less isolated.

1 INTRODUCTION

Individuals with an at-risk mental state (ARMS) are at high-risk of developing psychosis. They often experience a significant reduction in functioning and comorbid psychological conditions (Fusar-Poli, Nelson, Valmaggia, Yung, & McGuire, 2014). These individuals can be assessed for meeting ARMS criteria through the comprehensive assessment of an at-risk mental state (Yung et al., 2005). The transition rate for psychosis ranges between 20% and 40% (Larson, Walker, & Compton, 2010), whilst 40% maintain ARMS symptoms after 6 months (Tor et al., 2017). A high proportion of the individuals who are no longer ARMS meet criteria for another condition, with similar poor outcomes (Lin et al., 2015). In England, recommended intervention for ARMS includes individual cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with or without family intervention (FI, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2014).

Carers of individuals experiencing psychosis have increased levels of anxiety, worry, and depression, which impacts on their caregiving (Jansen et al., 2015; Wang, Chen, & Yang, 2017). Some family members experience fear and trauma (Onwumere, Bebbington, & Kuipers, 2011), whereas others experience stigma and guilt (McCann, Lubman, & Clark, 2011). The exacerbated levels of worry can increase feelings of responsibility and uncertainty as to whether families are acting and communicating appropriately (Coker, Williams, Hayes, Hamann, & Harvey, 2016; Kumar, Sood, Verma, Mahapatra, & Chadda, 2019). When carers perceive themselves to have high levels of unmet needs, this can negatively impact on the extent of their caregiving and their quality of life, suggesting that it is imperative to address these concerns earlier rather than later (Lal et al., 2019; Poon, Harvey, Mackinnon, & Joubert, 2017). Caregivers of individuals with first episode psychosis (FEP) identified wanting education and support in how to improve the relationship with the individual, recognize and respond to symptoms and help to reduce their own fears, worries, and anxieties (Kumar et al., 2019; Lal et al., 2019).

Interventions for families of FEP have been associated with improved carer psychological well-being and caregiving experiences (Addington, McCleery, & Addington, 2005), increased understanding of psychosis over time (McWilliams et al., 2010), reduced burden and negative expressed emotions (Kapse & Kiran, 2018), and improved coping skills and confidence in responding to difficulties (Onwumere et al., 2017).

There is limited research with relatives of individuals with ARMS. Izon, Berry, Law, Au-Yeung, and French's (2019) qualitative study identified barriers and facilitators to caregiving amongst family/carers of individuals with ARMS. Barriers for family members included a lack of understanding around individual's symptoms, limited confidence in how to support them, and unproductive coping strategies impacting on their own health and/or well-being. Quick access and involvement of services, family member's own social support, and open communication with the at-risk individual facilitated the caring role.

Considering the recommended interventions and early service involvement for at-risk individuals, we might expect reduction in worry, improvements in family member well-being, and similar outcomes to families of FEP individuals. That is assuming all individuals have access to the same standard of treatment, with family members feeling supported. However, with the ongoing and deteriorating symptoms for some individuals over the first year, some family members may experience new caring responsibilities, as well as new challenges that were not previously identified.

The current study aimed to understand the different types of changes, similarities, and reflections of those family/carers 12 months after taking part in the original qualitative interviews (Izon et al., 2019). This study is the first of its kind to use a qualitative longitudinal methodology to capture the nuances and outcomes of supporting someone at ARMS over 12 months. Giving family/carers a voice would provide richer data and explore micro-level impacts from involvement with services. This study incorporated the previous term “family/carers” to capture the varied relationships and support from all participants.

2 METHOD

2.1 Design

The study was embedded within a feasibility randomized control trial, the Individual and Family Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (IFCBT) trial (Law et al., 2019). The therapy (IFCBT) involved combined individual CBT and FI, typically with one family/carer. Irrespective of an individual's allocation, all participants were able to access or continue with their treatment as usual, typically but not always, enhanced care from an early intervention service (NICE, 2014). Fourteen family/carers participating in the feasibility trial completed qualitative interviews upon entry to the trial and were invited to take part in a follow-up qualitative interview after completion of their final trial assessment (12 months later). The current study received ethical approval by the Research Ethics Committee (16/NW/0278) as part of the main feasibility trial. The study conforms to recognized standards of European Medicines Agency Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

2.2 Procedure

At 12 months, 10 of the 14 family/carers agreed to a qualitative interview. The first author conducted all face-to-face, semistructured interviews at the family/carer's home. The topic guide covered the relationship, family/carer's understanding of symptoms, and hopes for the future and outcomes over the past 12 months (see Table 1). Interviews were audio recorded and lasted approximately 45 min. Participants were given £10 to thank them for participating. All interviews were transcribed and entered into NVivo11 qualitative analysis software. Any identifying information was removed in order to protect participant anonymity.

| Baseline qualitative interview | 12-month qualitative interview |

|---|---|

| Please explain your beliefs and understanding of what's going on with (your daughter). | Please explain your beliefs and understanding of their health and any changes over the past year? |

| Please describe/explain how you are feeling. | Please describe and explain how your feelings have changed over the year? |

| What challenges have you experienced? | What challenges did you experience in the past year? |

| What help and support, if any, have you sought? | In the past year, what support have you received that you found helpful? |

2.3 Analysis

The study utilized a two-stage analysis, guided by Braun and Clarke's (2006) thematic analysis and a framework analysis to integrate and compare themes and subthemes both across-case and within-case analyses (Spencer, Ritchie, Ormston, O'Connor, & Barnard, 2014). Thematic analysis facilitated an in-depth understanding, whilst maintaining the flexibility of an approach to develop a theoretical model, whereas framework analysis enabled data comparison of themes across multiple time points.

2.4 Stage 1

Stage 1 involved utilizing the thematic framework from the 14 interviews coded into themes and subthemes at baseline (Izon et al., 2019). The themes and subthemes were revisited for each participant to ensure that they accounted for the 10 who took part in the second interview and not exclusively for the four who did not.

2.5 Stage 2

Coding was both based on the prior publication themes and subthemes (Izon et al., 2019) but also grounded from the 12-month data (see Table 2). A mixed method approach was adopted. Deductive analysis was used to make comparisons, identifying changes and reflections at 12 months, whereas inductive analysis monitored new themes to account for novel family/carer experiences. Codes were clustered into a table of themes and subthemes and compared within and between time points for each participant and across participants. The authors accounted for changes in psychosis state over time (transition to FEP, meeting criteria for ARMS or no longer ARMS) and treatment received.All authors engaged in discussions through bimonthly supervision, suggesting alternative interpretations with constant comparisons within and across interviews to establish rigour and validation of results. Where the authors disagreed, further discussion and analysis of the data were undertaken until agreement was reached. For example, the 12-month interviews were initially coded into the themes and subthemes from the baseline analysis (Izon et al., 2019). The authors' decision for the themes to focus on the clinical implications was influenced by family/carers' providing recommendations and reflections during the 12-month interviews. Subthemes from the baseline analysis were retained, and new subthemes grounded from the data were included, which provided a more comprehensive structure of the results (see Table 2).

| Baseline | Development phase | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1 | Expectations and knowledge | Personal factors of the family/carer | Looking after your own well-being |

| Subtheme | Expectations and feelings of frustration with the mental health system | Health and wellbeing; work life balance; accessing emotional support; practical coping strategies | Life stressors on one's health and well-being |

| Subtheme | Feelings of uncertainty | The importance of peer supporta | |

| Theme 2 | Personal factors of the family/carer | Accessing additional support from family intervention (FI) | |

| Subtheme | Health and well-being | Expectations and knowledge; feelings of uncertainty | Breaking down myths and increasing family/carer understanding |

| Subtheme | Work life balance | Feelings of uncertainty | Increased hope but maintained worry |

| Subtheme | Accessing emotional support | ||

| Subtheme | Practical coping strategies | ||

| Theme 3 | Aspects within the relationship | Aspects within the relationship | Communicating openly with the individual |

| Subtheme | How communication can ease emotional challenges | How communication can ease emotional challenges | Importance of openness in reducing fear |

| Subtheme | Responsibility for the individual | Helpful humoura | |

| Theme 4 | Expectations and knowledge | Engaging with services for the individual | |

| Subtheme | Expectations and feelings of frustration with the mental health system | Frustrations and persistence | |

| Subtheme | Responsibility for the individual | Carer identity |

- Note: The “development phase” was the first integration of analysis involving both the baseline and 12-month data. This was further developed to include new themes from the 12-month data.

- a New theme grounded from the 12-month data.

2.6 Reflexivity

Four of the authors had experience working in services with people experiencing psychosis and advocates of psychological therapies to psychosis, with three authors involved in the IFCBT trial. One author had direct experience of mental health services as a carer of a daughter with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The first author completed the original interviews, 12-month interviews, and had contact with both family/carers and individuals for trial assessments at baseline, 6 and 12 months in the capacity of a research assistant. The first author was aware that their rapport with participants may have influenced family/carers' responses.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics from baseline and 12-month interviews can be found in Table 3.

| Baseline | 12-months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables of interest |

Individual N = 14 |

Family/carer N = 14 |

Individual N = 10 |

Family/carer N = 10 |

| Therapy: eTAU | 8: 6 | — | 8: 2 | — |

| Statea of psychosis (N, %) | ||||

| ARMS | 14 (100%) | — | 3 (30%) | — |

| FEP | — | — | 2 (20%) | — |

| No longer ARMS | — | — | 5 (50%) | — |

| Age | ||||

| Mean (years) | 21.15 (5) | 40.29 (12) | 20.8 (3) | 44.1 (10) |

| Range (years) | 17–34 | 17–56 | 18–27 | 23–54 |

| Gender (N, %) | ||||

| Males | 9 (64%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (50%) | 1 (10%) |

| Females | 5 (36%) | 13 (93%) | 5 (50%) | 9 (90%) |

| Ethnicity (N, %) | ||||

| White British | 12 (86%) | 12 (86%) | 9 (90%) | 9 (90%) |

| White Mixed | 1 (7%) | 1 (7%) | — | 1 (10%) |

| Caribbean | 1 (7%) | — | 1 (10%) | — |

| Any other mixed background | — | 1 (7%) | — | — |

| Family/carer (N, %) | ||||

| Parent | — | 9 (64%) | — | 8 (80%) |

| Sibling | — | 1 (7%) | — | 1 (10%) |

| Partner | — | 4 (29%) | — | 1 (10%) |

- Note: All data N (%) or mean (standard deviation).

- Abbreviations: ARMS = at-risk mental state of psychosis; eTAU = enhanced treatment as usual; FEP = first episode psychosis.

- a Individuals state after assessment on the CAARMS (Yung et al., 2005) to assess whether they were still ARMS had transitioned to psychosis or were no longer ARMS threshold at 12-month follow-up.

Four of the original 14 family/carers disengaged from the IFCBT trial and the qualitative interview. Three of the four family/carers who were not followed-up at 12 months were partners who had separated from the individual. The final family/carer reported ill health at time of follow-up. Of those four family/carers, two of the individuals were seen and were no longer at ARMS, whereas the other two individuals disengaged from the IFCBT trial and their states were unknown.

At 12 months, three individuals who were followed up still met ARMS criteria, two transitioned to FEP, and five no longer met ARMS criteria. All eight of the family/carers who received the therapy took part in the 12-month interview, whereas only two of the six who received eTAU participated. Of the eight who received therapy through the trial, individual CBT ranged between 2 and 25 sessions (median = 15.5) and FI ranged between 0 and 6 sessions (median = 3.5). One family/carer engaged with the therapist separate to the individual.

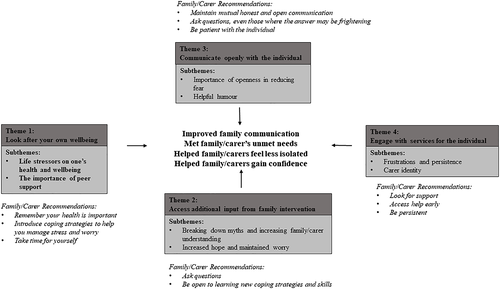

Four themes fit into the LACE model (see Figure 1). The model includes facilitating factors that can support family/carers of ARMS individuals from the themes and subthemes. The model includes recommendations for family/carers grounded by the 12-month data. The authors included the recommendations in the figure to provide accessible tips and advice for future family/carers from those with experiences of supporting ARMS individuals. The centre section includes the experiences at 12 months for some family/carers, when facilitating factors within the key themes were recognized and assimilated. All themes were important in the resulting positive changes for family/carers, as characterized by the arrows.

3.2 Theme 1: Looking after your own well-being

During the 12-month study involvement, family/carers continued to report stressful life events beyond their supporting role to an individual at-risk of psychosis. Social support continued to facilitate the caring role; however, some family/carers reported seeking support from their General Practitioner (GP) to discuss accessing medication or therapy for themselves. Some reported ongoing unmet needs and continued challenges, as well as processing the emotional and psychological distress associated with supporting an ARMS individual.

3.3 Life stressors on one's health and well-being

It probably doesn't help my depression. I don't sleep because I'm worried about her, you know, it wears you down. It's just that's been something else on top of everything that's been happening. (Parent 7)

I was doing a lot of things to try and cope with my level of stress to then be able to support (him). I was reading a lot of self-improvement books. (Partner)

(Partner) tries, but he doesn't get it. I have got friends I can talk to but I don't. I try not to, it's just so … it's not really the kind of thing you go out and talk about. I did ask for counselling for myself and I have got an appointment but I asked last August, and I've got my appointment in April. So, the waiting list is horrendous. (Parent 1)

You need to find someone who's been through a similar experience and I think that's part of the reason that when people would say go to carers (groups), well me speaking to somebody who's got a child with spina bifida or you know, it's a totally different scenario, and I don't, I don't want to speak to somebody who is a carer for a blind person because the situation is so different. (Parent 6)

3.4 The importance of peer support

You can talk to your friends, but because they don't understand … I mean they're kind and everything, it's not like they're not kind but I don't think it's the kind of advice that I could get from a friend. (Parent 2)

I think unless you are caring for someone else with a mental health condition, you're not going to get it. If you can find anybody in a similar situation to you, talk to them, even if it's not the same, something similar. Puts it into perspective. (Parent 6)

3.5 Theme 2: Accessing additional support from FI

FI provided family/carers an opportunity to speak to an expert, ask questions, and gain confidence and knowledge in strategies to support ARMS individuals. The differences between family/carers who had exposure to an expert were apparent from their changes in perceptions, understanding, and language over time.

3.6 Breaking down myths and increasing family/carer understanding

I don't know whether “belittled” is the right word but I don't think I took her fears seriously. I used to think that she was being dramatic. (Parent 2)

The therapist helped me normalise the hallucinations and auditory and visual things he was getting and understand them and understand how common it was and not be so frightened of them. We were distressed about the situation. (Therapist) was so calm and it was so normal to them and not shocking and they would say and explain what your brain was doing at the time and sort of normalised it in a way and it wasn't as scary. (Parent 5)

Sometimes you just have to ground her and I recognise that now, not sort of like “don't be ridiculous,” because I think at that moment for her it is real. It's more about grounding her and saying, “what would make you think that?” (Parent 2)

I'm still frightened of the schizophrenia thing because I don't know, I know they're all permanent. (Parent 8)

3.7 Increased hope but maintained worry

I don't feel too bad about her future to be honest. If you'd have asked me that 12-months ago, I'd have been really quite concerned because I wasn't sure she actually [emphasis] wanted a future 12-months ago. (Parent 2)

Its small steps really and just making sure that they know that they can rely on you but yeah don't push them too hard. (Parent 1)

She's not mentally fit to go to work, I don't think she's mentally fit to just be in a social gathering, never mind being in work. (Sibling)

I've still got that worry that how long can he cope with his life being like it is. (Parent 8)

3.8 Theme 3: Communicating openly with the individual

Open and honest communication was deemed important by all carer/families. At 12 months, some family/carers felt more confident than at the beginning of the study, to ask challenging or frightening questions. However, many reported that when they did not understand or were frightened of the answer, they chose to ignore the situation. This negatively impacted on the relationship and was associated with the individual's isolation.

3.9 Importance of openness in reducing fear

I kind of see a positive in that I know more about what's going on with her, with her being a bit more open with me now, whereas before, when she was quiet and everything, she didn't want to talk and she didn't know how I'd react. (Parent 4)

I've learned that I'm able to deal with things that are sometimes like catastrophic. (Parent 3)

(The family) could ask me how he was doing and I could tell them because we were involved in the therapy and we weren't having to ask (individual) anything about it, because we [emphasis] knew, you know. We knew because we were involved and he might not have wanted to come out at first telling us anything and then he's still in this isolated, lonely place of dealing with it on his own. (Parent 5)

You'd go out to work in the morning and I wouldn't know what she'd do. I don't think she's hurt herself for some time, but I don't know. I don't ask the question because I know I don't want the answer. And that might be cowardly, so I just try not to think about it I guess. (Parent 2)

3.10 Helpful humour

Even the worst case scenario, you can find something funny in it. (Parent 6)

It's just stuff like that, that we have a bit of a laugh about, whereas normally I'd have gone “don't be ridiculous, we're poisoning you?” (Parent 2)

3.11 Theme 4: Engaging with services for the individual

Family/carers reported feeling relieved and lucky when a service was involved in their relative's care. They validated the importance of services support but identified that brief engagement from multiple services over 12 months was disruptive and unhelpful.

3.12 Frustrations and persistence

Don't wait, it sounds awful, but don't wait for the NHS or therapy which will take months and months, if you can afford it, pay for it. Have sessions with the person, have sessions on your own. (Parent 5)

I know it sounds really bad, phone 999 and tell them if they leave you, you are going to kill yourself, and they will section you, because the police will drop you there, that's what it takes for you to get a support package in place, do it, because I just feel like I wasted a year of my life, going back and forth to A&E with (individual) and never managed to even get a psychiatric assessment. (Parent 6)

I would tell them to go to the GP straight away. I would tell them to be quite persistent because I think it took a long time for us to get help. (Parent 2)

It sounds awful but I can actually not think about him during the day, whereas before I [emphasis] could not think of anything else. We are happier. Well you know, I'm happier. (Parent 5)

3.13 Carer identity

(Social services asked) do you still consider yourself to be a carer for him and I thought, I am really. (Parent 6)

I think as the years gone on it's been a little bit less intense than it was 12 months ago. It's been a supportive role really: taking him to appointments, listening a lot of the time and trying to help him rationalise things as well a lot, in his life. I suppose just being there you know … I would like everything to be okay and for my role to not be as intense but it's something that I don't think will ever happen. (Parent 8)

(I'm) just frustrated and worn out with it all. Just, I can't say I blame an individual, I think it's the system as a whole. People cope in different ways and I really don't think you should have to hit rock bottom before somebody does something. (Parent 7)

4 DISCUSSION

Over 12 months, four factors were important for family/carers to facilitate their caring role, which were summarized in the thematic map (LACE model, see Figure 1): Looking after your own well-being; Accessing additional support from FI; Communicating openly with the individual; and Engaging with services for the individual. All four aspects of the model were important to understand how family/carers' experiences had changed over time. For some family/carers, the four themes led to changes over the 12 months, including improving family communication, meeting family/carers' unmet needs, and helping them to feel more confident and less isolated in their family/carer role.

4.1 Changes over time

Over the 12 months, family/carers continued to experience ongoing stressors. At the beginning of the study, family/carers were more likely to prioritize the individual before themselves, neglecting their own well-being. They described accessing social support as a coping strategy; however, at 12 months, they reported more support was sought or needed to manage their own emotional and psychological distress. At 12 months, ARMS family/carers experienced unmet needs that impacted on their well-being, similar to relatives caring for individuals with FEP (Lal et al., 2019; Poon et al., 2017). At 12 months, FI had facilitated the change in understanding for some family/carers. However, family/carers who had no involvement with a therapist continued to minimize the symptoms of the individual or express ongoing fears at 12 months. Similar to FEP research, education and support for carers helped reduce family/carers' own fears, worries, and anxieties (Kumar et al., 2019; Lal et al., 2019). Reported worry around the individual's symptoms, employment, and future continued from the beginning of the study, but there was an increase in hope from family/carers of individuals having a future. Similar findings were found from McCann, Lubman, and Clark's (2011) qualitative study with FEP carers, who had accessed a FEP service for approximately a year. Despite the difficulties, carers reported developing hope as a caregiver. In comparison to the beginning of the study, some family/carers felt more confident to ask open questions to the individual. However, when conversations broached difficult topics, open communication was overlooked. This resulted in a continued absence of understanding for family/carers towards the individual's experiences and knowledge in how best to support them. This adds to previous research where improved coping skills and confidence can support families in responding to challenges (Onwumere et al., 2017). Some family/carers experienced continued feelings of frustration towards services, having felt dismissed about their initial concerns. These family/carers often had limited involvement with services and continued to act as sole advocates for the individual, thus strengthening their identity as a carer. Hughes, Locock, and Ziebland (2013) suggest that some relatives may embrace the term carer with pride and be more prepared to adopt it; however, additional factors are important, for example, cultural expectations or receipt of welfare benefits.

4.2 Look after your own well-being

A change from baseline to 12 months was that family/carers recognized the importance of their own health and well-being, with some describing themselves as a carer. Similar to FEP relatives, they reported being more worried about the individual, with their own well-being less of a priority (Lavis et al., 2015). FI focussed on the relationship and needs of the individual rather than exploring the relatives' psychological distress. At 12 months, family/carers identified that they needed support in processing their own emotional and psychological distress. A proportion of family/carers had accessed support from their GP and were either prescribed medication or referred to counselling. By 12 months, family/carers were able to recognize the importance of looking after their own health and well-being. This may have been facilitated through new knowledge or family/carers taking the time to prioritise themselves.

4.3 Access additional support from FI

FI provided family/carers educational support to understand the individuals' symptoms and feel confident in their role. The initial lack of understanding for ARMS family/carers was similar to those at FEP, which led to family/carers minimizing the severity of the symptoms and reducing the likelihood or delaying individuals from accessing support (Connor et al., 2016). Similar to carers of FEP, ARMS family/carers also acknowledged a lack of understanding of the individual's symptoms, which may have initiated self-stigma and feelings of guilt, fear, and worry (Connor et al., 2016; McCann, Lubman, & Clark, 2011). For relatives of FEP individuals, FI helped them to feel valued (Jones, 2009) and less marginalized (Shiers, 2004). Early involvement in services from family/carers of ARMS and contributions to the individual's care may therefore help relatives to feel empowered and valued.

4.4 Communicate openly with the individual

During the 12 months, some ARMS individuals had become withdrawn and isolated themselves from their family. Family/carers of ARMS recommended talking to the individual about their experiences rather than avoiding conversations. FI helped to facilitate open discussions and develop strategies together to improve communication within the relationship. Relatives play a pivotal role in sustaining individuals' engagements with mental health services (Chung et al., 2010; Connor et al., 2016). Open communication can help relatives engage with individuals and services, which would be imperative for individuals who transition to psychosis and withdraw or self-isolate from services.

At 12 months, humour was identified as helpful for aiding open communication between ARMS individuals and their families. Humour has previously been found to help carers across health conditions as a coping mechanism and an effective intervention for dealing with difficult situations (Williams, Morrison, & Robinson, 2014). At the initial interviews, this may not have been mentioned due to an absence of open communication, family/carers beliefs, and understanding of the individual's experiences or higher levels of fear and uncertainty for the individual's future.

4.5 Engage with services for the individual

Family/carers experienced challenges when first accessing support, which was reflected in their recommendations at 12 months to visit the GP early and to be persistent if not initially given support. Their reporting of someone else's health, rather than their own, was a significant obstacle to overcome. Families play an integral part in facilitating engagement with services, but this can be influenced by their attitudes, beliefs, and responses to the symptoms (Connor et al., 2016). Similar to FEP literature, family/carers experienced unfamiliarity and limitations in their knowledge to negotiate access to services (McCann, Lubman, & Clark, 2011). The experiences of ARMS family/carers were mixed due to the variations between services, expectations from relatives, and limitations in their understanding and knowledge of services.

4.6 Strengths and limitations

Qualitative work does not draw inferences about the prevalence of phenomena observed beyond the sample. The study looked to include a diverse sample that reflected the ARMS population and their families, albeit the majority of participants were white British. The study involved the nominated family/carer of IF CBT trial participants (Law et al., 2019), with only one partner and one sibling; therefore, family/carers were not necessarily representative. However, mothers representing the majority fit with previous literature, whereby mothers typically take on the caring role (O'Brien et al., 2006, 2008; O'Brien, Miklowitz, & Cannon, 2015; Schlosser et al., 2010).

Qualitative literature has been criticized for providing a retrospective outlook, with the potential to omit important details and experiences that may not reflect the current service context (Gladstone, Boydell, Seeman, & McKeever, 2011). This study explored family/carers' experiences and changes in relation to what they found helpful or challenging over their 12-month study involvement. Noble and Douglas (2004) argued that there is a need for greater attention to caregiving experiences, and this is the first study of its kind to provide an in-depth understanding of the changes, similarities, reflections, and experiences from family/carers of ARMS individuals over 12 months.

4.7 Future research

More engagement with male family/carers and partners is needed to understand similarities or differences in their emotional, physical, and psychological responses. Future qualitative research could look beyond 12 months or to more frequent interviews to help capture changes in perceptions and understanding more closely, as opposed to relying on retrospective recall. To assess the applicability of the study recommendations to the wider ARMS population and their families/carers, future quantitative research should investigate how introducing the recommendations impacts on outcomes for all family members.

4.8 Clinical implications

Future clinical implications could include peer support for relatives or ARMS family support groups to aid, validate, and normalize family/carer experiences. When feasible, inviting the entire family into sessions that focus on an Open Dialogue model could support the development of a shared understanding, tolerating uncertainty (Seikkula et al., 2006) and promoting respectful, collaborative family environments (Gidugu, Rogers, Gordon, Elwy, & Drainoni, 2020).

Not knowing what and from where support can be accessed was a challenge for family/carers in the current study. Services could look into the development of a resource in collaboration with expert family/carers to help and provide support to future families. This could include education to enhance understanding and challenge beliefs, normalize family/carers' experiences, and increase their confidence and recommendations from people with similar experiences.

5 CONCLUSION

Four aspects were important for family/carers in facilitating the caring role of an ARMS individual as seen in the LACE model (Looking after your own well-being; Accessing additional support from FI; Communicating openly with the individual; and Engaging with services for the individual). The LACE model explains how family/carers felt more confident and less isolated in their carer role, prioritized and improved open communication with the individual, and had their needs met. Novel implications from the study suggest that when feasible, services should involve family/carers of ARMS individuals in sessions with the individual and explore family/carer support strategies in managing their own distress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to all of the families who participated in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

David Shiers is expert advisor to the NICE centre for guidelines and a member of the current NICE guideline development group for Rehabilitation in adults with complex psychosis and related severe mental health conditions, and board member of the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH); views are personal and not those of NICE or NCCMH. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.