What is the relationship between fear of self, self-ambivalence, and obsessive–compulsive symptomatology? A systematic literature review

Abstract

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is one of the most debilitating health conditions in the world. There has been a vast amount of research into factors that increase the likelihood of developing OCD, and there are several explanatory models. Current cognitive models of OCD can be split into appraisal-based and self-doubt models. To date, cognitive–behavioural therapy for OCD (grounded in appraisal-based models) is the recommended treatment approach, and research into the importance of self-doubt beliefs has been somewhat neglected. This paper therefore aims to consolidate current research, utilizing a systematic review approach, to establish the relationship between fear of self, self-ambivalence, and obsessive–compulsive symptomatology. A systematic search was conducted based on inclusion criteria identified for this review. Papers were then individually appraised for quality and key data extracted from each paper. A total of 11 studies were included in the final sample. Fear of self and self-ambivalence were both consistently found to be significant predictors of obsessive–compulsive symptomatology. In particular, research suggests that there is a strong link between self-doubt beliefs and obsessions and obsessional beliefs related to OCD. Limitations of the review and suggestions for future research are made and applications to clinical practice discussed.

Key Practitioner Message

- It may be useful for clinicians to assess self-doubting beliefs during their therapy assessment process and to incorporate work on these in treatment.

- Targeting this in treatment could have positive long-term consequences in the form of reduced relapse rates and improved self-esteem, over and above purely symptom reduction.

- Assessment and treatment of self-doubt beliefs can be incorporated in currently utilized cognitive therapy for OCD.

1 INTRODUCTION

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is an anxiety disorder that is characterized by repeated intrusive thoughts, anxiety, and subsequent behavioural compulsions in an effort to rid oneself of the intrusions or feared consequences of non-compliance with compulsions. The World Health Organization ranks OCD as one of the 10 most debilitating conditions based on lost income and decreased quality of life (Veale & Roberts, 2014). This makes research into OCD, and in particular, areas that might be beneficial to work on in therapy with these patients, very important indeed. There has been a great deal of research into what might make someone vulnerable to developing OCD (Fontenelle & Hasler, 2008; Grisham, Fullana, Moffitt, Caspi, & Poulton, 2011; Rector, Cassin, Richter, & Burroughs, 2009), and research has focused on the importance of cognition in the development of OCD. This paper presents a systematic review, which focused on two associated areas of cognition in relation to OCD: self-ambivalence and fear of self.

Self-ambivalence is a term first used by Guidano and Liotti (1983) to introduce the idea that an individual may not have a stable and concrete sense of themselves, part of this being a fear that they may somehow be a bad person. This may relate to a “feared self,” a concept that has been introduced relatively recently within OCD research (Aardema et al., 2013) and refers to the idea of a “self” that an individual is afraid of becoming. The theorists behind both ideas suggest that fear of self-beliefs and self-ambivalence are common amongst people who suffer with OCD. Despite increasing evidence in support of this idea, these concepts are yet to be incorporated into the cognitive models of OCD that are currently utilized in clinical practice. As a result, there is a need to review current research to establish the role of fear of self-beliefs and self-ambivalence in the development of OCD.

Cognitive–behavioural models of OCD emphasize the impact of beliefs on the development of the disorder (Rachman, 1997; Salkovskis, 1985). In particular, Steketee, Frost, and Cohen (1998) found several belief types that are common to those that experience OCD. These include beliefs around responsibility, over-importance of thoughts, perfectionism, and intolerance of uncertainty. These cognitive–behavioural models all suggest that intrusive thoughts and images are universal experiences, which only develop into clinical OCD as a result of certain beliefs about the intrusion, leading to misinterpretation of the intrusion itself. The models propose that it is the misinterpretation of these intrusions as having some deeper meaning that causes anxiety and subsequent behavioural responses. Appraisal-based models have developed over the years from considering the importance of responsibility interpretations (Salkovskis, 1985) to thought–action fusion (Rachman, 1993) and on to incorporating core beliefs that are common to those who experience OCD (OCCWG, 1997). The therapeutic protocol outlined by Wilhelm and Steketee (2006) advocates working on these beliefs within cognitive therapy for OCD, as a means of therapeutic shift.

Alongside the development of these appraisal-based models, other cognitive theory and research around OCD have focused on the importance of perceptions about the self and identity in the progression of obsessions and compulsions (Doron, Kyrios, & Moulding, 2007; Doron, Kyrios, Moulding, Nedeljkovic, & Bhar, 2007; Guidano & Liotti, 1983). In particular, it has been found that beliefs regarding the self and the world predicted obsessive–compulsive (OC) symptom severity, over and above beliefs outlined in “traditional cognitive–behavioural models of OCD,” that is, appraisal-based models (Doron, Kyrios, Moulding, Nedeljkovic, & Bhar, 2007). This is interesting as it highlights a noteworthy construct, which has been neglected in commonly used therapeutic cognitive models of OCD.

The different cognitive models can be divided into appraisal-based models, which highlight concepts such as responsibility (Salkovskis, 1985) and thought–action fusion (Rachman, 1993; Rachman, Thordarson, Shafran, & Woody, 1995) as being important, and self-doubt models, such as those described in more detail below. This is a somewhat arbitrary distinction, however, as one could argue that, for therapeutic purposes, these models need not be seen as discrete from one another and could be integrated. If, for example, a person's self-doubt beliefs were key to the development of their OCD, it would be rational to target them within the course of therapy. This being agreed, it is worth questioning why self-doubt models have not yet been incorporated into commonly used cognitive therapies. One answer to this question could be their focus on what could perhaps be seen as more dynamic beliefs about the self, which may be influenced by context and change over time. However, as one aim of cognitive therapy for OCD is to modify beliefs that impact OCD symptoms, this argument may not be sufficient to ignore the importance of self-doubt beliefs, as the inherent assumption of cognitive therapy is that beliefs are susceptible to modification and therefore dynamic.

Developing on investigation into self-doubt in OCD, researchers have studied the concept of self-ambivalence as a phenomenon commonly experienced by people who experience obsessions (Bhar & Kyrios, 2007; Bhar, Kyrios, & Hordern, 2015). This concept was first introduced by Guidano and Liotti (1983), who theorized that people with OCD have a “double view of themselves” and state that this causes the person to have a need for certainty (to find out which view is the true one) and perfection (to act in such a way to conform to the more positive of the two views of self). These authors suggest that, in the context of an unacceptable intrusion, this need for certainty and perfectionism provides a context for the development of obsessions and compulsions. If the unacceptable intrusion activates the feared self, the person is likely to pay attention to the intrusion and attempt to neutralize it, which, evidence suggests, increases the likelihood of further intrusions. It has been suggested that an individual with an ambivalent or fragile self-view experiences intrusions due to a distrust of themselves. That is, intrusions that they will do something bad arise because the person distrusts that they are a good person (Aardema & O'Connor, 2007). This idea is notably a different theoretical perspective from appraisal-based models, though in practice, treatment might use similar approaches. The discussion of this review will consider further how these models could potentially be theoretically linked.

Later papers proposed that a central issue in clinical presentations that feature intrusive cognitions is the feared self—what an individual is afraid of becoming (Aardema et al., 2013). This concept was perhaps first introduced by Markus and Nurius (1986) when they presented the idea of “possible selves.” They highlight that the feared self is different for each individual, likely dependent on their own life experience and aspirations. This idea is situated alongside self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), which states that discrepancies between an actual and ought self are associated with “agitation related emotions” such as fear and anxiety. They describe the ought self as the person we feel we should be and the actual self as the person that we believe we are. This therefore suggests that when these concepts do not marry as one, the actual self becomes more analogous to the feared self (Markus & Nurius, 1986). This appears to be a useful way to conceptualize OCD, based on the thematic content of intrusions that are common to the disorder (such as concerns around morality, responsibility, and goodness). Ferrier and Brewin (2005) have highlighted, however, that the feared self had been neglected in OCD research, in favour of a focus on appraisal-based ideas (i.e., responsibility and thought–action fusion).

The idea of a feared self and its role in OCD was developed further in the inferential confusion model (Aardema & O'Connor, 2007), in which the authors suggested that intrusions are perceived as self-representations and the person with OCD confuses obsessional intrusions with reality. Aardema and O'Connor (2007) contested Salkovskis' (1985) assertion that intrusions appear at random into consciousness, by observing that intrusions have content that appears to be related to a feared self. This, they argue, provides evidence that intrusions are not random, but instead originate from beliefs about one's own identity. In this model, they further discuss ego-dystonic intrusions and refer to a “feared self” as being the reason these intrusions result in obsessions: the intrusions are both created and perpetuated by a distrust of the self-as-is. Treatment targets should therefore logically include modifying beliefs around distrust of the self.

There are several accounts of self-doubt in OCD, and they are not necessarily distinct from one another. Each account focuses on asking the question of why some people appear to place significant importance on thoughts as evidence of what type of person they are, over and above other evidence to the contrary. Aardema et al. (2013) suggest that although the feared self is likely related to self-ambivalence, it does not imply an underlying ambivalent self; however, they do not make a strong argument for differentiating their concept from Guidano and Liotti's (1983) self-ambivalence. Additionally, in their study of the feared self, Aardema et al. (2013) reported a very strong correlation between their measure of the feared self, the Fear of Self Questionnaire (FSQ), and an established measure of self-ambivalence, the Self Ambivalence Measure (SAM; r = .73). This calls into question how distinct these concepts, or measures of them, are. Aardema and Wong (2020) provide further elaboration on this matter by proposing a model in which fear of self is responsible for the occurrence and thematic content of obsessions and not just their interpretation. In this new conceptualization, Aardema and Wong (2020) propose that self-ambivalence (referred to as an incoherent sense of self) is a vulnerability factor for the later development of a feared self and that self-ambivalence is related to the occurrence of obsessions by virtue of it providing a context for the development of the feared self. In other words, self-ambivalence has an indirect relationship with the occurrence of obsessions that is mediated by the development of fear of self.

The position of this review is that, although theoretically, the concepts are different—with fear of self referring to a feared “bad” self, which one wishes to avoid, and self-ambivalence referring to more uncertainty about the goodness of the self—the nature of the concepts means that the two are highly correlated (i.e., a person who is high in self-ambivalence is more likely to have a high fear of self and vice versa). Both concepts are based on the idea that a person with OCD has a tendency to focus on possible (and feared) selves, rather than the self-as-is. As a result of this, the present review includes literature on both fear of self and self-ambivalence in relation to OCD. Related concepts will also be considered for review.

As yet, no systematic review has been conducted to synthesize the findings of the research into OCD and self-doubt models. This paper draws together this research, by means of systematic review, in order to address the following question: do fear of self and self-ambivalence predict OCD symptomatology?

Answering this question will provide additional evidence to inform therapeutic work with those with OCD, and in particular, it will provide further support for the potential benefit of incorporating therapeutic work on self-ambivalence and fear of self-beliefs in the treatment of OCD more widely.

2 METHOD

2.1 Search strategy

Search strategy was based on PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). Several databases were searched, and these were: PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Medline, and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection. Databases were searched using cross-search; therefore, specific results gained from each database are not available. Search terms used were Fear of Self OR Self Ambivalence OR Feared Identity AND Obsessive Compulsive OR OCD. Self-doubt was not included as a search term as this would likely yield too broad results. The search fields were limited to title and abstract, to increase probable relevance of papers. Searching was completed in January 2019 with no time limits.

2.2 Criteria for inclusion/exclusion

Studies were included if they documented primary research, the research was quantitative, they were conducted on adult samples, there was access to full text articles, they were written in English, a validated measure of OC symptomatology was used (e.g., Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory (OCI), Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles, & Amir, 1998), and the study was measuring an aspect of feared self or self-ambivalence. Studies included needed to have assessed whether feared self or self-ambivalence predicted variance in OC symptomatology. For the purposes of this review, we included papers referring to OC overall symptomatology and any symptom that has been evidenced to be common in OCD when referencing OCD symptomatology. These include, but are not limited to, obsessive beliefs, obsessions, doubt, thought–action fusion beliefs, responsibility beliefs, beliefs about contamination, or behavioural components of the condition such as washing and checking.

Papers utilizing both clinical and non-clinical populations were included in the review. Studies with participants who were documented as having a clinical diagnosis of another mental health problem were not eligible for inclusion, unless they were utilized as a comparison sample. However, many of the studies included used a population (non-clinical) sample and did not document whether any other mental health problems were present.

2.3 Study selection

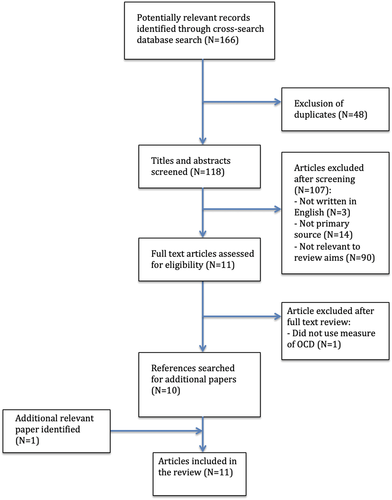

The search identified 166 potentially eligible results. Following the removal of duplicates (N = 48), titles and abstracts were screened for possible inclusion. Fourteen of the titles and abstracts screened revealed that they were not primary source research (i.e., they were book chapters or theoretical papers); three of them were not in English language and a translated version was not available. Of the 101 results remaining, 11 appeared to be potentially relevant from the initial screening of their titles and abstracts. Full texts for all of the articles were then accessed and reviewed. References were searched during the full-text review of each article in order to ensure that all relevant papers were located. During this process, one other potentially relevant paper was identified. Each paper (N = 12) was then assessed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and one study was excluded at this point as it did not use a valid measure of overall OC symptomatology and focused solely on measures of hoarding. The final inclusion total was therefore 11 papers. Figure 1 shows a summary of study selection and exclusion.

2.4 Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the final 11 studies: title, year, journal, authors, abstract, design, setting, sample size, characteristics of participants (i.e., gender, age), and country. Also extracted were measure of self-ambivalence/feared self used, measure of OCD/OCD symptoms used, whether the sample was clinical or non-clinical, data analysis strategy, and main findings. A data extraction spreadsheet was used in order to systematically record the data that were extracted from each paper.

2.5 Quality assessment of studies

The “Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields” (Kmet, Lee, & Cook, 2004) was employed to assess the quality of the 11 papers. These assessment criteria were used as used as it allowed for comparison of papers using a variety of methodologies. This framework considers 14 criteria on which to rate the quality of each paper. For the purposes of this review, three of the criteria (referring to random allocation and blinding) were removed, as they were not applicable to the studies that were included. Therefore, studies were assessed against 11 criteria. The framework provides definitions of each criterion and scoring guidelines on which to base individual scoring decisions on. The rater allocated a score of 2 if the criterion was satisfactorily met, 1 if it was partially met, and 0 if the criterion was not met. The maximum overall score a study could acquire was therefore 22.

3 RESULTS

As noted above, the search identified 11 studies that were relevant for inclusion in the review. Key information has been extracted from the studies and presented in tables below for ease of review and comparison. The tables include study characteristics, quality appraisal of studies, and results and outcomes of analysis.

3.1 Study characteristics

Characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1. This table includes data on design, setting, and country. Information about the samples across the studies is also presented, including sample size, age, and gender. Also presented is whether the study recruited a clinical or non-clinical sample in the design.

| Paper | Design | Setting | Sample size | Mean age (SD) | Gender | Country | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aardema et al. (2018) | Longitudinal | Community OCD setting | 93 | 38.65 (13.67) | 48.9% male, 51.1% female | Canada | Clinical |

| Aardema, Doron et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | OCD spectrum study centre | 144 | 38.8 (13.4) | 45% male, 55% female | Canada | Clinical and non-clinical |

| Aardema et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional | University | 292 | 1st*: 21.7 (5.92), 2nd*: 25.6 (11.63) | 1st*: 131 female, NR* 2nd*: 73 female | Canada | Non-clinical |

| Ahern et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | University | 120 | Female: 22.49 (7.96), male: 21.64 (7.26) | 95 female, 25 male | Australia | Non-clinical |

| Bhar and Kyrios (2007) | Cross-sectional | OCD patients, other AD*, non-clinical | 391 | 19.55 (3.27), 43.78 (13.92), 36.16 (11.24), 36.42 (11.42) | 70.6, 70.7, 62.9, 78% female, respectively | Australia | Clinical and non-clinical |

| Bhar et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | OCD treatment centre | 62 | 36.05 (11.58) | 59.7% female | Australia | Clinical |

| Ferrier and Brewin (2005) | Cross-sectional | Psych anxiety services and controls | 61 | 43.2 (13.58), 47.33 (13.08), 37.75 (13.87) | OCD = 8 male, 16 female, AC* = 4 male, 17 female, NAC* = 5 male, 11 female | UK | Clinical and non-clinical |

| Jaeger et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | University and social media | 221 | 26.4 (9.2) | 155 female, 3 NR* | Australia, US, UK | Non-clinical |

| Melli et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | OCD treatment centre | 83 | 33.21 (10.01) | 67.1% male | Italy | Clinical |

| Nikodijevic et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Community | 463 | 25.17 (7.47) | 291 female | US, Australia | Non-clinical |

| Seah et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | Majority university | 439 | 23.2 (8.4) | 75% female (328) 25% male (109), <1% (2) “other” | Australia | Non-clinical |

- Abbreviation: OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder.

- * 1st/2nd = study 1 or 2 in same paper, NR = No Response, AD = Anxiety Disorder, AC = Anxious Controls, NAC = Non-Anxious Controls.

3.1.1 Participants

The total sample size across 11 studies was 2,170. Three of the studies recruited an entirely clinical sample, whereas five of the studies utilized an entirely non-clinical sample within their research. Three studies used both clinical and non-clinical samples, for comparison purposes. All studies reported both age and gender of participants. Average ages for samples varied substantially, from 19.55 (Bhar & Kyrios, 2007) to 47.33 years (Ferrier & Brewin, 2005). Average age between clinical and non-clinical samples also varied considerably, with age of non-clinical samples averaging early 20s and age of clinical samples averaging late 30s. All but one of the studies had a significant majority of female participants. Female participants made up 72% of the total sample across 11 studies. The studies reported that the rest of the samples comprised male participants, other than in two studies (Aardema et al., 2013; Jaeger, Moulding, Anglim, Aardema, & Nedeljkovic, 2015) in which four participants across the two studies did not report their gender and another study (Seah, Fassnacht, & Kyrios, 2018) in which two participants recorded their gender as “other.”

3.1.2 Design

Ten of the 11 studies utilized a cross-sectional research design. The other (Aardema, Wong, Audet, Melli, & Baraby, 2018) utilized a longitudinal, within-participants design, assessing the same participants before and after treatment to look at changes in symptoms and fear of self-beliefs within participants.

3.1.3 Context

The constructs of self-ambivalence and fear of self as related to OCD have been studied in several countries across the western world. Six of the studies were conducted in Australia, three in Canada, two in the United Kingdom, and one in both Italy and the United States. Two studies utilized data from more than one country. One study (Melli, Aardema, & Moulding, 2016) utilized an Italian translation of the FSQ to assess its validity. Settings of research varied, but studies were predominantly composed of research conducted in clinical environments such as OCD treatment centres or psychological therapy services and in non-clinical environments such as universities and through social media recruitment, dependent on required study sample.

3.1.4 Materials utilized

Employed measures of OCD symptom or severity are detailed in Tables 3 and 4, alongside measures of self-doubt. Measures of OCD varied substantially across the studies. The most commonly used measure of OCD was the OCI (Foa et al., 1998), followed by the Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire (OBQ, OCCWG, 2001) and the Vancouver Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory (VOCI, Thordarson et al., 2004). The Padua Inventory (Sanavio, 1988), Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (YBOCS, Goodman et al., 1989), and Dimensional Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (DOCS, Abramowitz et al., 2010) were also utilized. Each of these measures has been shown to be reliable and valid measures of OCD or obsessive beliefs.

As noted, measures of self-doubt employed are also presented in Tables 3 and 4. Four studies used the FSQ (Aardema et al., 2013) alone, four used the SAM (SAM, Bhar & Kyrios, 2007) alone, and two studies utilized both measures. Both of these measures have been shown to be valid and demonstrated good reliability over a number of studies. One study (Ferrier & Brewin, 2005) did not use the FSQ or SAM and utilized the Intrusion-Related Self-Inferences Scale, which was designed specifically for the study. The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was reported at .95, with test–retest reliability at .60. As this was a new measure developed specifically for this study, it is important to be aware that its reliability had not been established across different studies.

3.2 Quality appraisal of studies

The included studies were assessed using 11 of the 14 criteria from the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields (Kmet et al., 2004). As noted above, three criteria were removed for brevity, due to lack of applicability to any of the studies. In particular, the criteria removed refer predominantly to randomized-control trials than to cross-sectional studies and therefore were not relevant to the studies included in this review. The scoring instructions for the framework were followed, and each study was given a rating for each of the remaining 11 criteria. Each study was also provided with a total score out of 22. The quality appraisal ratings for each of the assessment criteria can be seen in Table 2. Ratings of the papers ranged from 95% to 82% and were assessed to be of very good quality.

| Paper | Question/objective sufficiently described? | Design evident and appropriate? | Selection method described and appropriate? | Subject characteristics described? | Outcome measure well defined and robust? | Sample size appropriate? | Analysis described & appropriate? | Estimate of variance reported? | Controlled for confounding variables? | Results reported in sufficient detail? | Conclusions supported by results? | Total score/22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aardema et al. (2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| Aardema, Doron et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Aardema et al. (2013) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Ahern et al. (2015) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| Bhar and Kyrios (2007) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Bhar et al. (2015) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Ferrier and Brewin (2005) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| Jaeger et al. (2015) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Melli et al. (2016) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Nikodijevic et al. (2015) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Seah et al. (2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

The Standard Quality Assessment Criteria (Kmet et al., 2004) were used as it allowed for comparison of papers using a variety of methodologies. Three of the papers assessed received a 95% rating using this scale and were assessed to be particularly strong papers. These were particularly strong papers. These were Aardema, Doron et al. 2017), Bhar and Kyrios (2007), and Seah et al. (2018). Contrastingly, the weakest rated study in this review was that of Ahern, Kyrios, and Moulding (2015), although it still received a relatively high score of 18/22. The main identified problems in this paper were not sufficiently reporting design and sample selection, which makes it difficult to directly replicate the research presented. The papers were blind co-rated, and interrater reliability was high (α = .855, p = .003). Of the total scores for all papers (total 22), the raters agreed completely 46% of the time, had 1-point discrepancies 36% of the time, and had 2-point discrepancies the remaining 18% of the time. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and agreement on final scores.

Though the numeric rating scales can be useful as a guide, it should be noted that the criteria within this tool are not exhaustive and without their own limitations. Indeed, there are also strengths of the studies that are not highlighted in using the tool alone. It is important to assess the studies qualitatively, as well as quantitatively, to ensure that important issues that affect the quality of the papers are not missed. For example, a strength of Aardema et al.'s (2018) study is that they reported non-significant results alongside their significant results. This is a strength of the paper as publishing null findings helps to overcome some of the issues around publication bias (Easterbrook, Gopalan, Berlin, & Matthews, 1991). This was the only paper to report null results when considering fear of self and self-ambivalence as predictors.

When considering the dimensions on the quality appraisal tool, all papers were marked down by 1 point on their sample size being appropriate. Though the sample sizes of many of the studies were deemed subjectively appropriate, none of the studies included a description of having conducted a sample size power calculation, and as a result, it is therefore difficult to assess whether the sample sizes used were for measuring the observed effects.

The selection of participants also appeared to be predominantly appropriate; however, only three studies utilized both clinical and non-clinical samples (Aardema, Doron et al., 2017; Bhar & Kyrios, 2007; Ferrier & Brewin, 2005). This was a strength of these studies as it allowed for comparisons and examination of the relationship between self-doubt beliefs and OCD across the spectrum of symptom severity. One study would have benefitted from further clarity around participant selection (Aardema et al., 2018) as it was not clear from the write up whether the same participants had been used in previous research (Aardema, Doron, et al., 2017), as both papers appeared to recruit from the same source. This paper was therefore marked down on this criterion as sample selection was deemed to not be reported in sufficient detail.

Some further study limitations were highlighted using the quality appraisal tool. For example, several studies failed to make the study design explicit (Ferrier & Brewin, 2005; Melli et al., 2016; Nikodijevic, Moulding, Anglim, & Aardema, 2015). This could cause problems for replicability of these studies. Two studies also both failed to adequately explain or justify the method of sample selection (Ahern et al., 2015; Nikodijevic et al., 2015).

Despite the highlighted limitations, all studies were felt to be of sufficient quality for results to be interpretable and useful to answer the question in the context of this review.

4 RESULTS OF ANALYSIS

The primary significant findings from the studies are shown in Tables 3 and 4. For ease of reporting, analysis tables have been split into those studies that used regression analyses to analyse data (eight studies) and those that used other statistical techniques to analyse data. Other analytical techniques utilized were ANOVA and Bayesian modelling. As the review question was initially quite broad, the main aspects of OCD that were highlighted within the papers have led the reporting of results. As might be expected, each of the papers highlighted findings relating to different aspects of overall OC symptomatology. The significant OC concepts associated with self-doubt beliefs across the studies can be categorized into overall OC symptomatology, obsessions, obsessional beliefs, doubt, and contamination. Results have therefore been reported under these headings.

| Paper | OCD symptom measure (Criterion variable) | Measure of self-doubt beliefs (predictor variables) | r2 | Standardized beta | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aardema et al. (2018) | VOCI—Total | FSQ | .321 | .280 | NS |

| SAM | −.075 | NS | |||

| VOCI—Contamination | FSQ | .193 | 0.42 | <.007 | |

| SAM | −0.147 | NS | |||

| VOCI—Checking | FSQ | .217 | .034 | NS | |

| SAM | −.133 | NS | |||

| VOCI—Repugnant obsessions | FSQ | .403 | 0.361 | <.007 | |

| SAM | 0.063 | NS | |||

| VOCI—Hoarding | FSQ | .098 | −.052 | NS | |

| SAM | −.038 | NS | |||

| VOCI—Just Right | FSQ | .197 | .146 | NS | |

| SAM | −.039 | NS | |||

| VOCI—Indecisiveness | FSQ | .229 | .153 | NS | |

| SAM | −.047 | NS | |||

| Aardema, Doron et al. (2017) | VOCI—Obsessions | FSQ | .36 | 0.45 | 0.004 |

| Aardema et al. (2013) | OCI—Total | FSQ | .45 | 0.2 | 0.009 |

| SAM | 0.31 | <.001 | |||

| OCI—Obsessions | FSQ | .51 | 0.18 | 0.014 | |

| SAM | 0.45 | <.001 | |||

| OBQ | FSQ | .60 | 0.53 | <.001 | |

| SAM | 0.28 | <.001 | |||

| Ahern et al. (2015) | VOCI | SAM | .06a | 0.3 | <.01 |

| Bhar and Kyrios (2007) | Padua Inventory | SAM—SA | .337 | 0.232 | 0.004 |

| SAM—MA | 0.169 | 0.013 | |||

| OBQ—Responsibility | SAM—SA | .401 | 0.27 | 0.000 | |

| SAM—MA | 0.332 | 0.000 | |||

| OBQ—Perfectionism | SAM—SA | .423 | 0.403 | 0.000 | |

| SAM—MA | 0.215 | 0.000 | |||

| OBQ—Importance of thoughts | SAM—SA | .431 | 0.336 | 0.000 | |

| SAM—MA | 0.387 | 0.000 | |||

| Bhar et al. (2015) | YBOCS | SAM | Not reported | −0.41 | 0.005 |

| Melli et al. (2016) | DOCS—Unacceptable thoughts | FSQ | .47 | 0.64 | <.001 |

| Seah et al. (2018) | OCI | SAM | .35 | 0.2 (US) | <.001 |

| OBQ | SAM | .48 | 0.28 (US) | <.001 |

- Abbreviations: DOCS, Dimensional Obsessive Compulsive Scale; FSQ, Fear of Self Questionnaire; MA, moral self-ambivalence; OBQ, Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; OCI, Obsessive Compulsive Inventory; SA, self-worth ambivalence; US, only unstandardized Beta reported; VOCI, Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory; YBOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale.

- a Change in r2 with addition of predictor variable.

| Paper | OCD symptom measure | Measure of feared self | Bayesian regression value | ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaeger et al. (2015) | OCI-R (OCD symptoms), inference process task (doubt) | FSQ | 2.25*(control)/1.50* (checking) | N/A |

| Nikodijevic et al. (2015) | OCI | FSQ | 3.8*(control), 1.2*(checking), 1.8*(doubt) | N/A |

| Ferrier and Brewin (2005) | Padua Inventory | Intrusion-Related Self-Inference Scale | N/A | F = 28.88** |

- Abbreviations: FSQ, Fear of Self Questionnaire; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; OCI, Obsessive Compulsive Inventory.

- * significant coefficient defined where the 95% credible interval does not include zero.

- ** p<.001

Effect sizes have been reported, where possible, to enable the reader to interpret the strength of the effect as well as the directionality. Effect sizes (r2) for regression are categorized using Cohen's (1988) criteria (under 0.15 = small, 0.15–0.35 = medium, 0.35+ = large). Standardized betas for the regression analyses are also reported, to allow the reader to assess the individual predictive power of the relevant predictor variables (FSQ and SAM). Effect size was not reported in the paper that used ANOVA (Ferrier & Brewin, 2005) or the two papers that used Bayesian modelling (Jaeger et al., 2015; Nikodijevic et al., 2015).

4.1.1 Overall OC symptomatology

Self-ambivalence was found to be a significant predictor of OCD overall symptom severity across all but one study (Aardema et al., 2018), in which neither fear of self nor self-ambivalence was found to be significant individual predictors of overall OC symptomatology; however, the effect size of model as a whole was medium (r2 = .321). This is interesting as Ahern et al. (2015) found that, in their sample, SAM was a significant predictor of OC symptomatology in a study using the same measure of OCD (VOCI); there was a small but significant change in the model with the addition of SAM as a predictor. Aardema et al. (2018) utilized a clinical OCD population, whereas Ahern et al. (2015) used a non-clinical sample for their study, which could partially explain the different pattern of results. However, Aardema et al. (2018) also had a smaller sample size, which may have resulted in limited power to detect the effect. Without the power calculation for the sample size, it is difficult to draw conclusions based on these non-significant findings. Similar differences were also not seen across other studies utilizing clinical and non-clinical samples. In four out of the six studies that looked at self-worth ambivalence's (SA) ability to predict OCD symptoms, a medium to large effect size was reported. One of the remaining two papers, Ahern et al. (2015), did not report the overall effect size but noted that the SAM was also a significant predictor of OC severity, and the authors showed that the addition of the SAM into the regression model increased the predictive power of the model (change in r2 = .06). In another study (Bhar et al., 2015), the SAM was found to be a significant predictor of overall YBOCS score, but results were negatively correlated (β = −.41). This is inconsistent with findings from all other studies, though this is the only study in the sample that utilized the YBOCS to measure overall OC symptomatology.

Fear of self was also found to be a significant predictor of OCD symptom severity in all but one (Aardema et al., 2018) of the studies that looked at the predictive ability of the FSQ in determining OCD symptom severity. The two papers that reported effect size also showed medium to large effects of the overall model. Despite quality appraisal suggesting that Aardema et al.'s (2018) paper is of high quality, it is difficult to interpret how much weight to put on results that are inconsistent with other findings when the paper lacks evidence of a sample size calculation. Another point for consideration as to why results appear to be inconsistent with others is that Aardema et al.'s (2018) paper was different to the other papers in this review in that it analysed change scores before and after treatment, rather than predictive ability of FSQ or SAM at a single point.

Fear of self was also found to be a significant predictor of OCD symptom severity when utilizing Bayesian modelling (Jaeger et al., 2015; Nikodijevic et al., 2015); however, reporting of effect size was not apparent in these papers.

One paper (Ferrier & Brewin, 2005) utilized a measure of self-doubt that was developed specifically for the study, namely, the Intrusion-Related Self-Inferences Scale. The authors conducted an ANOVA looking at difference between a clinical sample of people with OCD, an “anxious control” sample and a “non-anxious control” sample. They found that the OCD group drew significantly more negative self-inferences based on their intrusions than did both other groups. They did not report an effect size for the difference between groups. The Padua Inventory was used to measure OCD symptomatology in this paper.

4.1.2 Obsessions

All four papers (Aardema et al., 2013; Aardema et al., 2018; Aardema, Doron, et al., 2017; Melli et al., 2016) that looked at the extent to which fear of self predicts obsessions or obsessional thoughts found that the FSQ significantly predicted obsessionality, with all papers reporting large effect sizes for the model. Only two papers (Aardema et al., 2013; Aardema et al., 2018) looked at the relationship between obsessions and self-ambivalence, using the SAM. Of these papers, only one (Aardema et al., 2013) found that SAM was a significant predictor of obsessions, with both papers reporting a large effect size for the model as a whole (.40 and .51, respectively). Despite one of these papers not finding the SAM to be a significant predictor of obsessions, this seems too small a sample of studies to enable the drawing of conclusive results. Again, the Aardema et al. (2018) paper found non-significant results, where others had. Further research is required in this area to enable conclusive evidence.

4.1.3 Obsessional beliefs

Contrary to this, three papers from the sample (Aardema et al., 2013; Bhar & Kyrios, 2007; Seah et al., 2018) studied the extent to which self-ambivalence predicted obsessional beliefs, utilizing the OBQ (OCCWG, 2001). Each of these papers found that self-ambivalence was a significant predictor of obsessive beliefs. These papers all reported large effect sizes, ranging from .40 to .60. Furthermore, one paper also found that the SA and moral ambivalence (MA) subscales of the SAM also both individually significantly predicted the “responsibility,” “perfectionism,” and “importance of thoughts” OBQ subscales. Effect sizes within this paper were all reported as large. The largest effect reported within this study was that of the ability of the SAM to predict beliefs around the “importance of thoughts” (r2 = .43). When broken down further, however, the SA subscale appeared best able to predict perfectionistic beliefs (β = .40), over and above the ability of the MA scale to predict any belief subscale. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the theoretical underpinnings of both of these concepts. This paper highlights the extent to which self-doubt beliefs are intrinsically related to those beliefs highlighted within “appraisal-based” models.

Only one paper in the sample had studied the extent to which fear of self was able to predict obsessive beliefs (Aardema et al., 2013). This paper found that fear of self was significantly able to predict obsessive beliefs (β = .53), with a large effect size for the model, inclusive of the SAM (r2 = .60). Further research into the relationship between fear of self and obsessive beliefs is warranted. Future studies would need to move beyond cross-sectional designs to begin to establish whether fear of self-beliefs predate obsessive beliefs or vice versa.

4.1.4 Doubt

One study in the sample looked at the ability of fear of self-beliefs to predict doubt (Nikodijevic et al., 2015). They found that, though fear of self did significantly predict higher baseline levels of doubt and greater fluctuation in doubting, they did not predict fluctuation in doubt over and above symptoms of OCD. The authors conclude that this provides evidence of a mediation model, suggesting that fear of self is related to doubt because fear of self influences OC symptoms, which, in turn, influences doubt. Fear of self alone was not able to significantly predict doubt. However, within this paper, the design of the research was unclear, which makes results more difficult to interpret. Additionally, as this was a cross-sectional sample, we are unable to determine causality. Therefore, although the authors conclude that this pattern of results provides evidence of a mediation model, we must be cautious and emphasize that this evidence only supports the idea that this is a reasonable hypothesis, rather than providing conclusive evidence, as such. Nevertheless, theoretically, it is perhaps unsurprising that feared self and doubt would indeed be related, due to the nature of both concepts. Further to this, given that self-ambivalence is defined as “the co-presence of positive and negative self-evaluations” (Riketta & Ziegler, 2006, pp. 219), it seems likely that self-ambivalence, as a concept, would also be inherently related to doubting. Unfortunately, however, none of the papers in this review studied the relationship between these factors. This would warrant investigation in future research.

4.1.5 Contamination

Only one of the 11 studies (Aardema et al., 2018) looked specifically at the ability of the FSQ and SAM to predict contamination fears. They found that fear of self significantly predicted contamination-based fears and reported a medium effect size for the model as a whole (r2 = .21). Contrary to this, they did not find that self-ambivalence, as measured by the SAM, was a significant predictor of contamination fears. This is interesting in that these constructs are highly correlated (Aardema et al., 2013). However, one issue worth considering here is the possible impact of multicollinearity on the results of this study. In examining the individual correlations, changes in the SAM and FSQ were found to be significantly correlated, with a strong, though not extremely high, correlation (r = .51). SAM was also significantly moderately correlated with contamination fear (r = .30), as was FSQ, with a slightly stronger correlation (r = .40). Given the similarity of these two constructs (FSQ and SAM), it is possible that only one (FSQ) has emerged as a significant predictor. This may be, for example, because self-ambivalence is a subcomponent of a broader concept of fear of self. Again, due to lack of power calculation reported in the study, it is also difficult to ascertain whether the sample size was sufficient to obtain required power to detect an effect. Due to the limited sample of studies specifically looking at contamination, there is argument that further research into this area is warranted.

5 DISCUSSION

The present review represents the first attempt at consolidating the current body of research evidence assessing the relationship between self-doubt (i.e., collectively the concepts referred to in the literature as “fear of self,” “self-ambivalence,” and “intrusion-related self-inferences”) and OCD symptomatology. Based on the theories of feared self and self-ambivalence in OCD, several pieces of empirical research have been conducted to look at the association between fear of self and/or self-ambivalence and various aspects of OCD symptomatology. In particular, research has focused on the relationship between these concepts and things such as obsessions, certain obsessive beliefs, and other symptoms, as noted above. Despite significant research into this area, these self-beliefs have not yet been incorporated into the cognitive appraisal-based models of OCD that are commonly used in the treatment of the disorder in a clinical setting (e.g., Wilhelm & Steketee, 2006). Notably, however, inference-based therapy has been successfully utilized in working with individuals who suffer with OCD (O'Connor, Koszegi, Aardema, van Niekerk, & Taillon, 2009). This was developed from the inferential confusion model (Aardema & O'Connor, 2007) but is not currently recommended in the NICE (2005) guidelines, unlike cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). The aim of the review was to establish whether self-doubt beliefs were able to predict OCD symptomatology. Fear of self and self-ambivalence were used as the primary two concepts under the umbrella term “self-doubt”; however, one paper, which looked at intrusion-related self-inferences, was also included.

In summary, there is strong evidence that both fear of self and self-ambivalence are significant predictors of OCD symptomatology in general. This was a consistent finding across all but one (Aardema et al., 2018) of the studies included for review. This study looked at change in symptoms before and after treatment.

Given the above finding, it may also be helpful to establish whether some symptoms are more strongly predicted by self-beliefs than others. However, this was not possible within this study as meta-analysis techniques could not be used due to the small number of studies and substantial variability in measures of OC symptomatology. Further research to attempt to replicate the findings of these studies would be beneficial and may result in the ability to draw stronger conclusions about the relationship between self-doubt beliefs and individual symptoms of OCD. Nevertheless, some findings could be extracted from the studies included within this review, to offer some preliminary information.

In particular, the studies included in this review provide strong evidence of a link between obsessional beliefs and self-doubt. Both self-ambivalence and fear of self were consistent predictors of obsessional beliefs across all of the papers that were reviewed. More specifically, self-doubt predicts obsessional beliefs as measured by the OBQ (OCCWG, 2001). Similarly, both measures of self-doubt were also consistent predictors of overall OC symptomatology. The evidence therefore highlights that separately, self-doubt has a relationship with obsessive beliefs and overall OC symptomatology. This may provide some initial evidence that obsessional beliefs could be a mediating factor between self-doubt and OCD symptom severity.

The OBQ includes the following belief subscales; overestimation of threat, tolerance of uncertainty, importance of thoughts, control of thoughts, responsibility, and perfectionism. These subscales are synonymous with the beliefs highlighted as being common to those with OCD in appraisal-based models (Steketee et al., 1998; Wilhelm & Steketee, 2006). The fact that self-doubt appears to consistently be able to predict obsessional beliefs has implications for current theoretical understandings of OCD. This finding provides evidence that “appraisal-based” and “self-doubt” models are, indeed, not discrete from one another and could be integrated. Indeed, the originators of inference-based therapy note that their model can complement CBT (O'Connor et al., 2009). Indeed, studies of treatment outcome have shown successful results, with some highlighting a potential increased benefit for using inference-based approaches over cognitive appraisal-based approaches in working with individuals with poor insight (Visser et al., 2015), strong obsessional conviction (O'Connor et al., 2005), or for those who have previously been considered “treatment resistant” (Aardema, O'Connor, Delorme, & Audet, 2017). This has implications for treatment approaches and suggests that therapeutic work on modifying self-doubt beliefs and inferences could and perhaps should be incorporated into current cognitive behavioural (appraisal-based) models routinely utilized in therapy. As suggested in the introduction to this paper, it may be useful for clinicians to assess self-doubting beliefs during their therapy assessment process and to incorporate work on these in treatment. If an ambivalent sense of self is related to obsessive beliefs, it may be that targeting this in treatment would have positive long-term consequences for those individuals in the form of reduced relapse rates and improved self-esteem, over and above purely symptom reduction. Consideration of self-doubt may therefore be a useful addition to treatment protocols that focus on obsessive beliefs. Further research should aim to study this concept longitudinally—to take a large sample of young people and assess self-ambivalence and OCD symptoms. Participants could be followed up throughout early development to assess whether self-ambivalence does indeed precede OC symptomatology. This may allow us further understanding of the cognitive risk factors and mechanisms that influence the development of OCD.

Looking in more detail into the relationship between self-ambivalence and obsessive beliefs, Bhar and Kyrios (2007) found that, in particular, self-ambivalence was able to significantly predict the responsibility, perfectionism, and importance of thoughts belief subscales of the OBQ. Furthermore, the MA subscale within the SAM was able to predict both responsibility and importance of thoughts beliefs to a greater extent than the SA subscale. The SA subscale, on the other hand, was more able to predict perfectionistic beliefs. Future research may benefit from analysing the two subscales of the SAM individually, in order to further assess the impact of MA and SA on OCD symptoms independently. This may provide developments in theoretical understanding about the interplay between these constructs, as well as helpful information that could inform treatment approaches.

A further finding highlighted in this review is that all of the papers that studied both constructs found that that FSQ was able to significantly predict obsessions. This provides additional evidence that fear of self may relate to OCD by way of relating to the nature of obsessional thoughts (Aardema & O'Connor, 2007). Appraisal-based models (Salkovskis, 1985; Wilhelm & Steketee, 2006) would argue that it is the appraisal of intrusions that leads to the perpetuation of OCD, whereas inference-based models (Aardema & O'Connor, 2007) suggest that intrusions arise as a result of an ambivalent or fragile self-view, due to a distrust of themselves. The author proposes a new, combined theory: that self-doubt (or an ambivalent self-view) likely influences the nature, as well as the interpretation of intrusive thoughts, and this appraisal and the presence of ongoing intrusions perpetuate the self-doubt beliefs. These propositions would require empirical investigation. There is evidence to suggest that the intrusions that people experience are based on inferential confusion (the idea that intrusions are perceived as self-representations that are confused with reality, (Aardema, O'Connor, & Emmelkamp, 2006) and proposals that these obsessions develop dependent on core fears (Huppert & Zlotnick, 2012). There is also evidence that suggests that intrusions are related to highly valued aspects of self that are rated as more distressing (Rowa & Purdon, 2003). This might suggest that self-doubt in areas of felt importance impacts the types of intrusions one is likely to experience, which are then the most likely to be perpetuated by anxiety, leading to the development of OCD. Further research is required to assess this theory. Research could utilize a longitudinal design, following a cohort of participants and measuring both self-doubt beliefs and OCD symptoms over time, to try to ascertain whether one feature appears to precede the other. However, some aspects may also be amenable to experimentation, for example, by manipulating self-doubt and assessing the impact on one or more symptoms of OCD (e.g., checking).

The evidence supporting the ability of self-ambivalence to predict obsessional thoughts was more varied. Of the two papers investigating this, one paper showed a strong significant predictive effect (Aardema et al., 2013) and another, by the same first author (Aardema et al., 2018), suggesting that SAM was not a significant predictor of obsessional thoughts. In this instance, two different measures of OCD obsessions were used: the subscales from the VOCI and OCI. This might suggest that whether or not SAM predicts OCD symptoms is dependent on the measure used. Future research would benefit from replicating this study and utilizing other measures of OCD to assess this. Another possible explanation for this is the sample size difference between the two studies; Aardema et al. (2018) recruited 93 participants, whereas Aardema et al. (2013) recruited 292 participants. Therefore, one possibility is that the former study did not achieve sufficient statistical power to detect an effect. Without evidence of power calculations for required sample size, it is difficult to ascertain this. A final possible explanation for these differences is that Aardema et al. (2018) utilized a clinical sample, whereas Aardema et al. (2013) used a non-clinical sample, primarily comprising university students. A possibility is that there may not have been enough variation in overall OC symptomatology within the clinical sample to establish a significant effect.

Studies looking specifically at the relationship between self-doubt beliefs and doubt and contamination as symptoms of OCD are limited, and further research is required in this area to allow for the drawing of confident conclusions. The paper that did look at the link between self-doubt and contamination fears found mixed results, with FSQ highlighted as a significant predictor of contamination fears and SAM as not significantly predicting contamination. Multicollinearity, though, is a potential issue.

As the MA subscale of the SAM was found to be a significant predictor of importance of thoughts and responsibility, but not contamination (Bhar & Kyrios, 2007), it would be interesting for future research to assess the extent to which this concept could predict mental contamination, as opposed to the physical contamination fears that are perhaps better represented by the VOCI subscale. The contamination subscale on the VOCI has items such as “I am excessively concerned about germs or disease” and “I feel very contaminated if I touch an animal,” which may be less relevant to those people who experience mental contamination. Mental contamination can be described as having a feeling of internal dirtiness and a desire to cleanse, in the absence of a bodily contaminant, and is more commonly induced by psychological processes (Rachman, 1994). It may be that MA and indeed, fear of self, are theoretically more likely to predict mental contamination than fear of physical contaminants, as mental contamination is often triggered by moral violation, whereas physical contamination is not. Therefore, MA and fear of self are more likely to explain variability in mental contamination than physical contamination. Recent research has provided evidence in support of this idea in finding that mental contamination is a significant mediator of the relationship between fear of self and contact contamination (Krause, Wong, O'Meara, Aardema, & Radomsky, 2020). This line of theorizing is further supported by work by Rowa and Purdon (2003) who found that intrusive thoughts that contradict highly valued aspects of self are rated as the most distressing and Doron, Kyrios, and Moulding (2007) who found that those who valued morality but who felt morally incompetent displayed more obsession-like problems.

A general issue in the literature on self-ambivalence and fear of self is their specificity to OCD. Based on the finding that people with OCD did not differ from those with other anxiety disorders in self-ambivalence, Bhar and Kyrios (2007) concluded that self-ambivalence might be more appropriately conceptualized as being relevant to OCD rather than specific to it. Moreover, Higgins' (1987) self-discrepancy theory and subsequent investigations related to it suggest that internally inconsistent representations of the self are associated with a variety of affective difficulties. Nevertheless, irrespective of specificity to OCD, this literature review further supports arguments about incorporating a focus on fear of self and self-ambivalence in interventions for OCD.

5.1 Summary of proposed future directions

Significant further research is required to address questions raised as a result of this review. First, future longitudinal research could look to assess whether self-ambivalence and fear of self do indeed precede OC symptomatology. This would help to guide treatment approaches and our understanding of the development of OCD. Second, though not a research direction in itself, future research may benefit from analysing the two subscales of the SAM individually. This would enable further assessment of the impact of MA and SA on OCD symptoms independently. Third, additional research is required to assess the question of cause and effect about how self-doubt influences OCD: does it cause the intrusions themselves, or impact the interpretation, or both? Fourth, research into contamination and self-doubt beliefs is very limited. Further research is required in this area to enable the drawing of accurate conclusions. This could include research specifically looking at mental contamination, which may be more likely to be linked to fear of self and self-ambivalence (particularly the moral-ambivalence subscale) than studies of physical contamination fears.

5.2 Limitations

One limitation of the present review is that due to the differing statistical analysis used by included studies, it was not possible to conduct meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is favourable to systematic review alone, where possible, as it allows for the combining of effect sizes from multiple papers to increase statistical power and give a clear picture of overall findings (Gopalakrishnan & Ganeshkumar, 2013). The outcomes of this review are based on the authors' reading of papers alone, and thus, conclusions about effect sizes should be interpreted with care, as they have not been able to be statistically compared.

Second, this review only includes published research on the topic areas. To attempt to identify relevant unpublished research, an internet search was conducted and unpublished theses were included in the search process; however, no additional unpublished papers were yielded. Grey literature searches lack the systematic nature of database searching and therefore may fail to find relevant studies. Publication bias is therefore something to be mindful of when interpreting the results of this review, as evidence is suggestive of a steady increase in publication bias, particularly in the fields of psychology and psychiatry (Joober, Schmitz, Annable, & Boksa, 2012). This refers to the idea that papers that have findings in support of the null hypothesis are not published and there is a preference for studies with significant findings. Due to this publication bias, there may be additional research that found evidence in support of the null hypothesis, which has not been made available publicly and therefore was unable to be included in this review. This conclusion is supported by the fact that none of the papers included in the review yielded entirely non-significant findings.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The current paper represents the first attempt to draw together research that assesses self-doubt models of OCD and the links between the feared and ambivalent self and individual symptoms of OCD. Initial research provides strong evidence that fear of self and self-ambivalence are able to significantly predict OCD symptom severity. In particular, research suggests that there is a strong link between self-doubt beliefs and obsessions and obsessional beliefs related to OCD. Additional research is required to replicate and develop on current understandings. Though there were some limitations to the review, the results are highly valuable with regard to providing new theoretical questions and new directions for research in this area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Bob Patton, who provided feedback on this paper prior to submission. The authors received no funding from an external resource.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There were no conflicts of interest with regard to the production of this review.