Synergy in Child Neurology: Science, Collaboration, and Leadership – The 2024 Hower Award Lecture

1 Introduction

This is an exciting era in child neurology! The scientific state of the art is accelerating rapidly. New diagnostics and treatments are here – or are coming quickly. And our community of researchers, clinicians, and educators is becoming more diverse and increasingly representative of the children and families we serve.

Of course, we have our challenges. What does it take to be a successful researcher in the current climate? How do we best take care of the many patients who need us? How do we recruit new colleagues and retain them in the field? Who will be the next wave of child neurology leaders? None of these questions have easy answers, but the solutions come down to three fundamental values: great science, effective and consistent collaboration, and excellent leadership.

2 Great Science Requires Effective Collaboration

2.1 The Neonatal Seizure Registry (NSR) – Co-produced Research With Parents and Investigators

NSR is a collaborative of nine US centers with level IV neonatal intensive care (NICU) programs, level IV pediatric epilepsy programs, site investigators with expertise in neonatal neurology and epilepsy, dedicated clinical research coordinators, and outstanding parent partners. Together with Hannah Glass, I have had the privilege of leading this group over the last dozen years to accomplish practice-changing research in neonatal seizures.

-

The top three neonatal seizure etiologies are hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), stroke, and hemorrhage [1].

-

1 in 8 newborns with seizures at our tertiary care centers have neonatal-onset epilepsy [2].

-

Most neonates with epilepsy have a genetic etiology [2].

-

Almost all newborns with seizures are treated with phenobarbital [3]. Some neonates were discharged home on phenobarbital, while others had their antiseizure medication (ASM) discontinued before hospital discharge. The best predictor of this treatment decision was the study site [4].

Based on the above observations and informed by our parent partners, we designed NSR-II – an observational comparative effectiveness study, powered for non-inferiority, to evaluate whether discontinuing ASMs before discharge from the NICU was safe. We employed propensity-weighted analyses to allow for causal inference from an observational study design [5]. With nine participating NSR centers, we recruited 303 neonates with acute provoked neonatal seizures and evaluated the impact of discharge to home with any ASM versus discontinuing all ASMs before discharge on 24-month functional neurodevelopment and postneonatal epilepsy. Two-thirds of infants were discharged home on ASM. Of these, 68% received phenobarbital monotherapy, 12% levetiracetam monotherapy (parenthetically, this study occurred before the clear finding from NEOLEV2 [6] that levetiracetam is inferior to phenobarbital for the treatment of neonatal seizures), and 20% were discharged with more than one ASM [7].

Children were followed for 24 months to evaluate functional neurodevelopmental outcomes and the risk of epilepsy. All analyses, including pre-planned subgroup analyses for preterm infants and infants with HIE, demonstrated equivalent neurodevelopmental outcomes [7]. Importantly, the risk for postneonatal epilepsy was also not different between the groups [8]. However, there was a high risk of severe neurodevelopmental impairment and drug-resistant seizures among children with postneonatal epilepsy [8].

These practice-changing results were highlighted in the 2023 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) evidence-based guideline for the treatment of neonatal seizures. Recommendation 3 indicates that “following cessation of acute provoked seizures (electroclinical or electrographic) without evidence for neonatal-onset epilepsy, ASMs should be discontinued before discharge home, regardless of MRI or EEG findings.” [9].

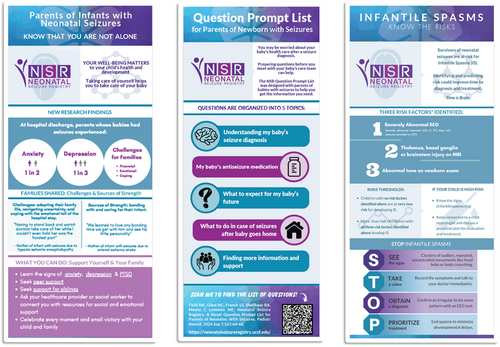

NSR parent partners and patient advocacy group representatives are integral to the team's impact. A parent representative from every study site, along with representatives from several advocacy groups, form our parent advisory panel. This group has met every month for more than a decade to advise the study investigators about the highest priority questions (resulting in published manuscripts [10, 11]), development of research protocols, assistance with protocol implementation and optimal retention strategies for long-term follow-up, review of data, interpretation of results, authorship of manuscripts and creative means of results dissemination (Figure 1). The parent advisory panel has also been integral in a long-term NSR study arm that examines parent and family well-being as they care for their infants with neonatal seizures [12-17].

Parents were the primary drivers of subsequent successful grant submissions to evaluate risk for infantile spasms after neonatal seizures (NSR-SPASMS) [18], pre-school and school-aged outcomes (NSR-Developmental Evaluation; NCT04337697), as well as the genetic underpinnings of the risk for postneonatal epilepsy (NSR-GENE; NCT05361070). Coproduction of research with traditional investigators and invested parents enriches every aspect of the work.

2.2 The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium (PERC) – Making Connections to Advance Clinical Care

PERC is a national organization of pediatric epilepsy centers whose mission is to perform collegial, collaborative, practice-changing research. At the same time as NSR was accelerating its research portfolio, excellent collaborative research was launching through PERC. The first two major projects were the National Infantile Spasms Consortium (NISC, led by Kelly Knupp) and the Early-Life Epilepsy Study (ELE, led by Anne Berg). These two related projects paved the way for fundamental changes in the way we evaluate and treat early-life epilepsy.

The 23 participating centers of NISC enrolled 629 infants with newly diagnosed infantile epileptic spasms syndrome from 2012 to 2018. Critical observations included that only three currently available treatments are effective for this epilepsy syndrome: ACTH, prednisolone, and vigabatrin [19-21]. Additionally, response to treatment was not predicated on hypsarrhythmia [22].

In parallel, 775 children with new-onset early-life epilepsies were enrolled from 17 PERC centers to form the ELE cohort. From these data, we learned the key value of genetic testing [23] and neuroimaging [24] to determine the epilepsy etiology, as well as the most common first-line treatments [25]. Leveraging the statistical methods we had learned from NSR, we evaluated the comparative effectiveness of levetiracetam versus phenobarbital for treatment of early-life epilepsy and discovered that levetiracetam was significantly more likely to provide seizure-freedom for children with non-syndromic epilepsy in the first year of life [26].

Continued collaboration with talented colleagues at PERC allowed additional high-impact analyses. For example, we learned that in spite of our knowledge about the best treatments, children who are Black or African American, or who have public insurance, are less likely than children who are White or who have private insurance, to receive standard treatment courses for infantile spasms [27]. Additionally, while it is traditional to wait for 2 weeks to assess treatment response, most failure of first-line treatment for infantile spasms is evident by Day 7 [28]. Thus, clinical protocols to reduce bias in treatment selection and to encourage a simple phone call to determine whether infantile spasms persist after 1 week of treatment could lead to more efficient and effective care for these vulnerable patients.

2.3 The Pediatric Epilepsy Learning Healthcare System (PELHS) – A Promising Next Step

PELHS (led by Zachary Grinspan) leverages the electronic health record, and dozens of dedicated and innovative collaborators, to glean key information from data clinicians enter every day into our patients' charts [29]. The promise of this model is to use informatics to rapidly gather and analyze data in iterative cycles to facilitate quality improvement initiatives and comparative effectiveness studies. A next step for PELHS and NSR is our NIH-funded study to leverage the electronic health record to determine the best second-line treatment for neonatal seizures, when phenobarbital fails, and to evaluate risk factors for postneonatal epilepsies.

2.4 Next Opportunities in Child Neurology – The Importance of Sleep Research

With the advantage of collaborations across multiple high-functioning clinical research networks, as well as my own work on neonatal sleep [30-33], it has become apparent that research on sleep is a key opportunity in child neurology. Our parent partners from NSR and from the Spina Bifida Association underscore sleep as a high priority for research [11]. Indeed, fully two-thirds of 5-year-old survivors of neonatal seizures had parent-identified sleep problems (three times the rate of sleep problems among healthy children [34]), with one-quarter screening positive for sleep-disordered breathing [35]. These observations are critical since sleep problems are treatable.

For otherwise healthy children, treating sleep disorders improves behavior and quality of life [36-40]. It stands to reason that children with neurological disorders will also benefit from such interventions – and emerging evidence supports this hypothesis [41]. Given that many children with neurological disorders have sleep problems, and parents identify these problems as key priorities, it is time for child neurologists to address sleep as a key strategy to improve outcomes for our patients.

To begin to address sleep as a modifiable risk factor for neurodevelopmental impairment, my team developed a research program designed to evaluate sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in infants with myelomeningocele. These infants are at risk for SDB given their high rates of hydrocephalus, Chiari II malformation, and infant surgery. Additionally, children and young adults with myelomeningocele are known to be at elevated risk for SDB [42]. Initial data suggest that most neonates with MMC already have SDB [43-46]. Our ongoing multicenter study will evaluate whether early detection and treatment of SDB is associated with measurable improvements in neurodevelopment (NCT04251806).

3 How Will We Change Clinical Practice Based on Breakthrough Research?

Since the state of the art is advancing so quickly, this is a crucial time to mindfully evaluate how the new data can be incorporated into clinical practice. Apart from our need for rigorous training in implementation science and quality improvement methodology, one of our field's main challenges is the limited number of clinicians available to care for children with neurologic disease.

In 2024, 177 medical students matched into US child neurology residency programs [47]. We do not currently have a systematic approach to quantifying the number of nurse practitioners or physician assistants in child neurology (personal communication, Mona Jacobson, president, ACNN), but such advanced practice providers are clearly a key element of expanded access to clinical care. To enable continued advances in the state of the art, it is crucial that every single one of these individuals succeeds and is retained in child neurology. And we need to recruit far more.

Early exposure to child neurology is an essential long-term strategy. From effective pipeline programs for school-aged children, to exposure to neurosciences in the undergraduate years, and learning from outstanding and inspirational clinicians in the early months of medical and nursing school, educators matter.

3.1 Active Support and Retention for Child Neurologists

Flexibility in career trajectory and day-to-day schedules, equitable compensation, and respect for the full range of professional pathways are key levers for support and retention of child neurologists. A critical part of increasing and diversifying the child neurology workforce is placing value on all types of careers in this vast field.

Academia has long rewarded research contributions, and educators are increasingly recognized for their impactful work. It is now essential that we recognize and reward the vital work of clinicians in child neurology. As a significant step forward, my work as Senior Associate Dean of Faculty Promotions & Career Development at Washington University in St Louis led to a recent revision of our faculty promotion criteria. Our updated appointment and promotion guidelines and recommendations (aptly named “APGAR”) now state: “While achievement of regional, national, or international reputation or publications shall receive appropriate credit, these serve mainly to demonstrate that the candidate's work is outstanding and impactful. Demonstrable professional excellence of faculty on the Clinician Track does not necessarily result in external reputation or published manuscripts. Therefore, external professional reputation and published manuscripts are not required for promotion on the Clinician Track.” [48] In the months since these updated criteria were implemented, many faculty members who were stalled in junior academic ranks have been promoted, or now see for the first time how their careers goals can be recognized through promotion at WashU Medicine. I hope that our experience in St Louis will be a model for other academic centers.

3.2 See It to Be It

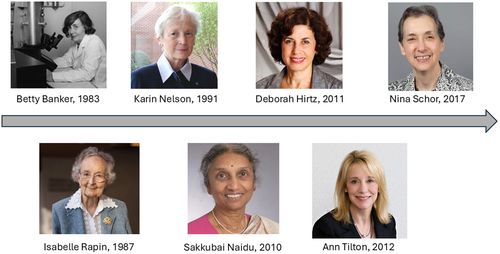

While women have made up more than half of board-certified child neurologists for the last 25 years, they remain under-represented at the highest level of leadership and recognition in child neurology [49]. Just three women have served as president of the Child Neurology Society (CNS) since 2000 (Ann Tilton, 2005–2007; Donna Ferriero, 2009–2011; Nina Schor, 2013–2015). Notably, Yasmin Khakoo became president-elect in 2024.

As the daughter of a Hower Award winner (Peter Camfield, 2009) and a CNS Lifetime Achievement Award winner (Carol Camfield, 2019), I have always been surrounded by outstanding academic child neurologists – many of whom are women. I am fortunate to have had personal connections with six of the seven women who received the Hower Award before me (Figure 2). All of them were highly accomplished leaders and have been personally generous with their time and talent. I am humbled to now be counted among them.

I realize that my good fortune of coming up in an environment enriched with outstanding role-models, mentors, clinicians, educators, and scientists accelerated my own career trajectory. I also know that for too many others, a lack of representation at the top of the field can be discouraging. Simply waiting for women to naturally “catch up” in the ranks of recognition and leadership is insufficient [50, 51]. It is clear that concerted efforts are needed to sponsor women for top leadership roles and prestigious awards. As demonstrated at the 2024 CNS meeting, such efforts can pay off – after encouragement of more diverse nominations, women earned the Hower, Sachs, Denckla, Dodge, and Brumback awards in this ground-breaking year.

Next, we as a profession need to make sure that 2024 is not an outlier and that gender representation among awardees and leaders becomes consistently reflective of the membership of the CNS. At the same time, it is very clear that our organization – and we as individuals – must address the unacceptably small number of child neurology leaders and awardees from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Many of the actions needed to address the gender gaps in child neurology may also be applicable to reduce disparities experienced by other demographic groups. I look forward to a day when it is not at all remarkable for a woman or a person from a historically under-represented background to be president of the society or selected for our most prestigious awards.

4 Fostering the Development of Leaders in Academic Child Neurology

It is clear that we need to develop excellent leaders in child neurology. There are countless open positions for division chiefs, section heads, and program leaders – not to mention department chairs in Pediatrics and Neurology. The CNS now has a committee on Leadership, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. This team is working to develop appropriate programming, but it is clear that support for emerging leaders must come from a range of sources – from national organizations to medical school offices of faculty development, to individuals who are willing to advise, mentor, and sponsor.

For senior child neurologists, this is a critical time to actively identify and develop emerging leaders. Challenging high-performers so they are constantly learning and performing at their highest potential is key for retention and career satisfaction – with benefit to the entire field and the children we serve. For emerging leaders, please take advantage of the opportunities offered by mentors and sponsors. I encourage you to engage with your local career development resources, as well as leadership development opportunities offered through the CNS and other professional organizations. Develop your professional network – and let your colleagues, mentors, and potential sponsors know about your career aspirations. Be bold with your vision, and be willing to put in the patient, incremental, daily work required to achieve that vision.

4.1 Mentorship, Sponsorship, Cheerleading

Service as mentors and sponsors has never been more important (Table 1). Mentorship is necessary for career progression at all stages. Many programs support junior child neurologists to establish their careers, but mentorship also remains critical at mid- and senior career stages. Traditional mentorship models, coupled with wonderful peer mentors, have been key to my success. I will always be grateful for my mentors – the senior attendings who marked up my papers and grants, the mid-career role model who held my infant son at my first CNS meeting so I could focus on Frances Jensen's excellent neonatal seizure lecture, and the peer mentors who push me to succeed at the highest levels while staying grounded as a human being.

| Mentor | Sponsor |

|---|---|

| Talks with you | Talks about you |

| Gives advice | Opens doors |

| Helps you out | Has your back |

| Suggests ways for you to get what you want or need | Advocates for you (even/especially when you are not there) |

| Tells you to believe in yourself | Believes in, and tells others about, your potential |

| Discusses your problems | Pushes you to strive for more |

| Says positive things when asked | Creates opportunities for you |

Just as mentorship is essential at all stages, sponsorship is also important throughout our careers. Taking the time to become a great sponsor allows us to leverage our connections to actively create opportunities for our colleagues – nominations for awards and leadership roles, invitations to write or review papers, serve on committees, give presentations, etc. For those being sponsored, I encourage you to take advantage of the opportunities you are offered (even when you feel too busy!). Recognize that your sponsor is invested in your success. Thank them for their confidence in you – and seek their advice and support to excel at the challenges they send your way.

Each of us can serve as mentors and sponsors. And we can all serve another vital role – cheerleader. In a high-pressure environment, when there is always another patient to see, student to teach, or grant to write, we don't celebrate enough. Graceful self-promotion is a necessary skill, but uncomfortable for many. It is very easy, however, to offer a “well-done” or to spread the word about a colleague's accomplishments. Fostering a culture of sincere celebration of the big and small wins can significantly improve the climate in which we all learn, grow, and work together for the purpose of improving the lives of children with neurologic diseases.

4.2 Child Neurology Needs You!

There has never been a better time to be a child neurologist – or a member of the CNS. Through excellent scientific and clinical collaborations, we are advancing the state of the art. Through outstanding leadership, we can shape the field to be inclusive – and representative of all demographics and career paths. Each of us has agency to make a difference in the moment and we all have influence that we can leverage for good. To this end, I invite you to be encouraged by my family's motto as you change the world through your lives and careers: Seek the Truth, Act in Kindness, Create Beauty, Do the Needful Deed.

Author Contributions

Renée A. Shellhaas: conceptualization, investigation, writing – original draft, methodology, visualization, writing – review and editing, resources.

Conflicts of Interest

RAS receives a stipend for her role as President of the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, serves as a consultant for the Epilepsy Study Consortium, and receives royalties from UpToDate for authorship of topics related to neonatal seizures. She receives payment for her work as an executive coach for physicians. She also serves on the ACNS Editorial Board.