Diencephalic Syndrome in Adolescents: A Case Series

Abstract

Introduction

Two pediatric patients presented with unintentional weight loss despite normal caloric intake. Both patients later developed neurological symptoms, and a neoplastic lesion was detected in the hypothalamic-optic chiasmatic region. The location of the tumor and the significant weight loss aligned with diencephalic syndrome (DES), which typically occurs in infants and young children. However, both patients were in their teens and thus greatly deviated from the normal age range of this disorder.

Methods/Results

After chart review we analyzed the patients with a focus on the similarities in their clinical course and final diagnosis. Both patients were ultimately diagnosed with DES. Managing the patients' tumors allowed them to experience significant weight gain and return to daily life activities.

Discussion

Although the exact pathogenesis for DES is not fully understood, the symptoms are associated with hypothalamic dysfunction. DES has been accepted as a disorder of the hypothalamic hunger and satiety control mechanisms. With both patients having tumors in the hypothalamic-optic chiasmatic region, it is expected that the growing mass would compress the hypothalamus and disrupt normal hypothalamic function. Because of the hypothalamus' role in hunger and satiety control mechanisms, it is logical that these disruptions could produce abnormal weight changes.

Conclusion

DES is a rare condition and typically only presents in infants and toddlers. Thus, this syndrome occurring in teenage populations represents a rare diagnosis in an unexpected demographic. The novelty of this presentation led to delays in diagnosis and effective treatment. Greater awareness of the occurrence of DES in atypical demographics is needed to ensure proper patient management.

Patient 1 Introduction

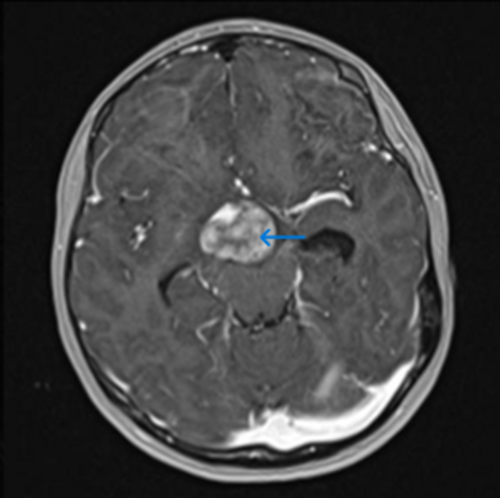

This 13-year-old adolescent girl presented to the pediatrician after experiencing morning nausea and vomiting for 3–4 months. She had also unintentionally lost 10 lbs over the course of a year. Initially, she was referred to gastroenterology. However, within a week of presenting to the pediatrician, she developed headaches. The headaches prompted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1), which detected a suprasellar nonsecreting astrocytoma that was later found to be positive for the BRAF V600E mutation. The mass projected up into the anterior aspect of the third ventricle, included cystic components, and involved the optic chiasm. The patient was diagnosed with an inoperable suprasellar juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma (JPA). Her tumor was considered inoperable as a complete resection was expected to cause blindness.

Nausea and vomiting were evaluated as a potential cause for the unexplained weight loss, but calorie counts and nutrition assessments did not support this. The patient reported appropriate caloric intake without significant loss to vomiting. Approximately 20 months after diagnosis, a G-tube was placed to aid in nutrition, and this allowed her to experience a small weight gain.

The patient came into our care approximately 2 years after diagnosis. She appeared very thin and weighed 81 lbs (36.7 kg) despite claiming normal to increased appetite. She presented for intractable headaches with migrainous features and with hydrocephalus, urinary incontinence, and left homonymous quadrantanopia, which progressed to left homonymous hemianopia over the course of her illness. Hydrocephalus and urinary incontinence improved with a shunt revision at that time, but her weight continued to be a struggle.

Patient 1 Clinical Course

Shunt replacement and then trials of gabapentin and nadolol led to transient improvement of her symptoms. Several short courses of oral dexamethasone also led to transient improvement in symptoms, including appetite. She never received prolonged steroids. Overall, however, her JPA was not responsive to conventional (thioguanine, procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine, carboplatin/vincristine [TPCV]) or targeted (dabrafenib, trametinib + dabrafenib) chemotherapies. Four months after her third shunt adjustment surgery, she received laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT). Her JPA was very responsive to LITT, and her headaches became more manageable.

Initially, the feeding tube allowed her weight to increase to 90 lbs, but she was still severely underweight and unable to maintain weight increases. Following LITT, her appetite increased and she maintained her weight gain. She was placed on a 1.5-month oral dexamethasone taper, and her weight increased to 114 lbs and then decreased to 108 lbs. Although the G-tube may have played a factor in her weight gain, it is unlikely to be the most influential intervention since she still had trouble gaining weight after its placement 4 months prior to LITT. Six months after LITT the G-tube was no longer needed and subsequently removed. The girl's ability to maintain weight without the G-tube indicates that targeting the tumor with LITT played the most significant role in her long-term recovery. Similarly, although the steroids assisted in her weight gain and helped to manage the tumor, they are unlikely to be the most influential factor in her weight gain since she received short courses of oral steroids prior to LITT to manage her headaches and still struggled with weight gain.

Patient 2 Introduction

This 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to the emergency department (ED) after unintentionally losing 10 lbs over 1 to 2-months. He had been continuously losing weight for 2 years, thought to be due to difficulty swallowing and decreased appetite. Despite his low appetite, his stepmother and father continued to encourage him to eat and maintain a normal caloric intake, which he did by forcing food consumption. As a result of his anorexia, he presented to the ED at a weight of 89 lbs and a body mass index of 13.85. He appeared underweight with a scaphoid abdomen. Additionally, he had a 3-month history of blurry vision and a 3-day history of left-sided ptosis. He was hypotensive (blood pressure 85/60 and dropping as low as 65/49), bradycardic (51 bpm and dropping as low as 36 bpm), and hypothermic (temperature 96.2°F). The patient also complained of intense headaches accompanied by slight photophobia and a pounding pain behind his eyes. Headache onset was 3 months prior to the emergency visit.

Patient 2 Clinical Course

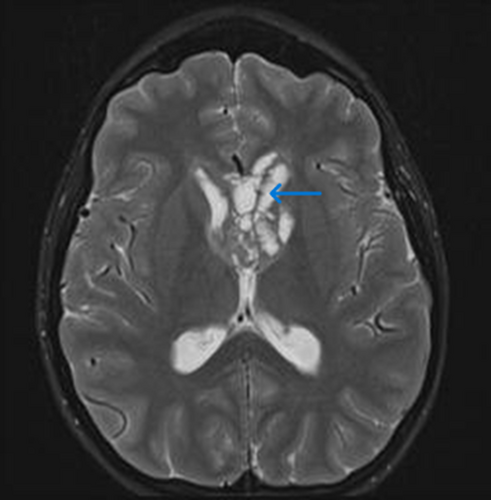

In the ED, the patient received an abdominal computed tomography scan, which revealed a dilated appearance of the proximal duodenum and a decompressed appearance of the duodenum as it crosses the midline behind the mesenteric vessels. The scan also showed trace nonspecific low-density free fluid layering his pelvis. He was transferred from the ED to the pediatric intensive care unit and received rapid crystalloid boluses to manage his hypotension. Consultations from a gastrointerologist, a nutritionist, and a neurologist were requested. The neurological examination at the time of the ED consultation confirmed the patient's left-sided ptosis and slowed speech without a definite visual field deficit. An MRI revealed a cystic and solid mass lesion with associated restricted diffusion (Figure 2). The mass was interposed between the dorsum sellae and basilar artery and extended superiorly posterior to the optic chiasm to extensively involve the anterior third and fourth ventricles and adjacent septum pellucidum. There was also evidence of the tumor spreading subependymally posteriorly along the third ventricle, into the cerebral aqueduct and fourth ventricle. A ventricular tumor biopsy revealed the mass was a germinoma. The patient was then started on cycles of etoposide and carboplatin to manage his germinoma. Addressing the patient's tumor with a combination chemotherapy treatment resulted in a present-day 20-lb weight gain despite chemotherapy.

Results

Both patients presented with a combination of severe, unexplained weight loss and neurological symptoms and were found to have tumors in the expected locations for diencephalic syndrome (DES). Both were ultimately diagnosed with DES.

Discussion

DES remains a rare diagnosis and an uncommon cause of failure to thrive in infants and children. Only about 100 patients have been reported.1 The syndrome is characterized by weight loss and emaciation despite normal caloric intake and the presence of a lesion on the optic chiasm or hypothalamus.1, 2 Associated symptoms include normal linear growth, normal or even precocious development, visual disturbances, hyperemesis, nystagmus, and endocrinopathies.2, 3 The lack of hyperemesis, visual symptoms, and nystagmus should not rule out the diagnosis, as the key features for diagnosis are unexplained weight loss and lesions in the characteristic locations.4 Although the exact pathogenesis is not fully clear, symptoms are associated with hypothalamic dysfunction. The hypothalamus is the center for neuroendocrine regulation of energy homeostasis, specifically the ventromedial nucleus, the arcuate nucleus, and the paraventricular nucleus. DES has been accepted as a disorder of the hypothalamic hunger and satiety control mechanisms, and new data theorize that an interplay between the dysregulation of the orexin (hypocretin) system, growth hormone, β-lipotropin, and other hormones play a role in the observed emaciation and hypermetabolic state.1, 5-7

The causative lesions for DES are commonly low-grade gliomas such as pilocytic astrocytomas. Other lesions such as craniopharyngiomas, suprasellar ependymoma, and germinomas have rarely been described as causing DES.8 The literature documents only one 11-year-old female patient and only a few male patients with DES caused by germinomas.9, 10 Astrocytomas associated with DES are larger, occur at younger ages, and are often more aggressive than other astrocytomas arising in this region.8 Prognosis is variable. Low-grade gliomas on the optic pathway present as slow-growing tumors, and worse outcomes are associated with delayed diagnosis. Deep hypothalamic tumors usually have poorer clinical outcomes and more often result in anorexic or hypermetabolic symptoms.3

DES only rarely affects adolescents or adults and has been described as a disease of young children, with diagnosis usually occurring at 18 ± 10.5 months.2, 3, 8 Both of our patients, however, were adolescents who experienced weight loss eventually associated with neurological symptoms, and both had intracranial masses: the girl, a suprasellar pilocytic astrocytoma; the boy, a germinoma involving the posterior optic chiasm. Having a germinoma as the cause of DES in the male patient adds to his rare presentation. Diagnosis was delayed in both patients due to a lack of awareness of DES presentation in this age group; a brain MRI was not considered until headaches developed.

Our patients provide excellent case studies for the general pediatrician or pediatric subspecialist in gastroenterology, endocrinology, or neurology who may have the opportunity to diagnose patients with similar presentations. Thankfully, after effective treatment of their respective tumors, both patients' emaciation and neurological symptoms improved or resolved. This response to treatment corroborates their diagnoses of DES, as weight loss and additional symptoms typically resolve with treatment of the tumors responsible for the dysregulation of metabolic homeostasis.

Conclusion

Although DES typically occurs in infants and toddlers, it should also be included in the differential diagnosis for adolescents presenting with neurological symptoms and weight loss despite normal caloric intake or weight loss alone in the absence of other clear etiologies. As with our patients, a delay in diagnosis occurs often and can worsen the prognosis if the tumor progresses. Therefore, early imaging and hormonal testing for patients with the aforementioned presentation will ensure timely diagnosis and treatment of DES and the underlying cause.

Author Contributions

Toritseju I. Kpenosen: Conceptualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Owen N. Chandler: Conceptualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Scott I. Otallah: Conceptualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing, supervision.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.