Opioid neurotoxicity: A case series and review from members of the Child Neurology Society Neurocritical Care Special Interest Group

Varina L. Boerwinkle and Imani H. Sweatt are coprimary first authors.

Abstract

Objective

The Child Neurology Society 2023 Annual Meeting Neurocritical Care Special Interest Group discussed pediatric opioid use–associated neurotoxicity with cerebellar edema (POUNCE). Inspired by the discussion and the suspicion of an underrecognized severe form of the disorder, we provide a case series and literature review on this important and emerging topic.

Methods

The meeting was moderated by coauthor DSM, with formal presentation by coauthor AG, and supplemented with a supporting case by coauthor VLB. The attendees, by show of hand, were queried for experience with direct care of children in the critical care unit with neurotoxicity from opioid exposure. These meeting elements informed our literature review and case series.

Results

A key focus of the meeting was the importance of interdisciplinary communication regarding POUNCE, emphasizing the necessity for neurosurgical assessment due to mass effect. Approximately 10 of 40 attendees, representing different US hospitals, reported caring for children with opioid neurotoxicity and concern for increased intracranial pressure. Described during the meeting was a 2-year-old girl with opioid exposure, rapidly worsening neurological exam, and transforaminal herniation concerning for severe POUNCE syndrome and impact on brain networks by resting-state functional magnetic resonanance imaging (rs-MRI). After surgical decompression did not improve her neurological function, she underwent rs-MRI, electroencephalogram, and MRI. The networks indicated better neurological function than the exam, consistent with outcome. In contrast, the second patient, was an 11-month-old boy with fentanyl exposure who was treated for opioid overdose and closely monitored clinically. He did not require surgical intervention and has recovered well.

Interpretation

These patients add to the few publications documenting the management of POUNCE, which may require urgent posterior cranial fossa decompression, and highlight the potential for good outcomes. Additionally, this is the first report documenting rs-fMRI for this condition, which was consistent with the patient's outcome.

Introduction

The opioid crisis is promoting illicit fentanyl and other opioid overdose in children. One complication, leukoencephalopathy, is described in a variety of resultant syndromes, including chasing the dragon leukoencephalopathy syndrome; cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion syndrome; acute toxic leukoencephalopathy; and pediatric opioid use–associated neurotoxicity with cerebellar edema (POUNCE) syndrome.1 Because each syndrome is rare, the nature and extent of difference between these syndromes is unclear.

However, recently reported pediatric patients appear to have the characteristics of POUNCE, which include cerebellar edema, altered mental status, and cardiorespiratory depression due to opioid toxicity.1 Early detection and intervention may be necessary to achieve immediate and long-term recovery.1 There is a paucity of pediatric literature to guide care in severely affected patients, which appear to threaten life due to increased intracranial pressure.

Inspiration from the 2023 Child Neurology Society Annual Meeting Neurocritical Care Special Interest Group Topic

The 2023 Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society Neurocritical Care Special Interest Group members discussed recent patients with POUNCE (one of the three discussed cases is not included due to planned inclusion in another article) in whose consciousness was temporarily reduced with good recovery. With a show of hands, about a fourth of 40 attendees from different US institutions reported directly caring for a child with POUNCE. The format of the meeting was a round table moderated open discussion among all attendees. The group discussed the utility of external ventricular drain placement and intracranial pressure monitoring to guide medical management of patients with posterior fossa mass effect and reduced consciousness. The central concern and related solutions further focused on communication barriers between care services, including the need to foster collaborative working relationships between medical and surgical teams through regular structured meetings for case reviews. One evolving element further illuminated in the discussion was the medical provider promoting the need for extra ventricular drain but the neurosurgical member promoting caution against rushing toward this intervention without focal brainstem findings on current exam. The risk discussed for extra ventricular drain placement included worsening or precipitation of upward cerebellar herniation, while the cons of waiting were missing the window for reducing intracranial pressure and patient deterioration.

These cases represent the published spectrum of severity of POUNCE syndrome, with the first one illustrating findings of focal brainstem function deficits, which furthers the expert group's discussion of peri-surgical focus. Here we outline successful life saving neurosurgical intervention for severe POUNCE, postoperative management, and novel whole-brain resting-state functional imaging for neuroprognostication.

The institutional review boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine and Nemours Children's Health granted waivers of consent for this report.

Patient 1 description

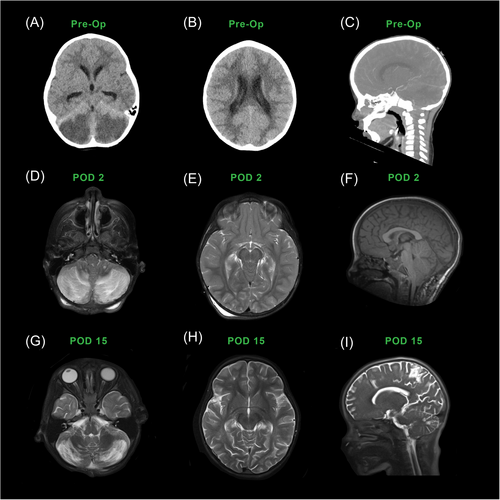

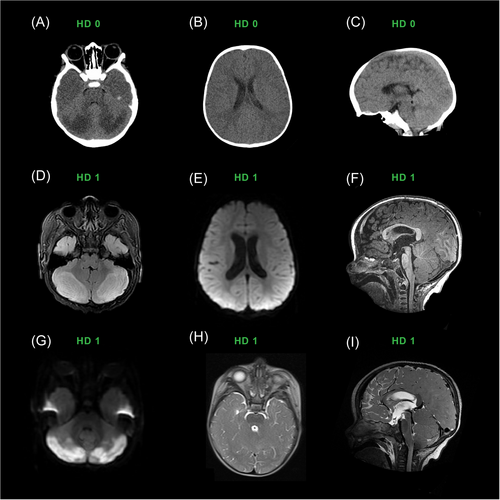

A normally developing 2-year-old girl with a history of in utero drug exposure presented with unresponsiveness despite improvement with parent-administered naloxone a day earlier. Her unresponsiveness and cyanosis fluctuated between repeat dosages of naloxone by emergency medical services and emergency department staff, and she regained command following in all extremities and spontaneous eye opening, to a Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale of 15, with positive urine toxicology for fentanyl. Computed tomography (CT) of the head was concerning for bilateral cerebellar infarctions (Figure 1), so she was prophylactically intubated and life-flighted to our tertiary center. Upon arrival, she was completely unresponsive, had fixed and dilated pupils, and had full-body dystonic extensor posturing, concerning for imminent death due to brain herniation. After consultation with colleagues in pediatric neurocritical care and neurosurgery, she promptly underwent a suboccipital craniectomy and extra-ventricular drain placement.

Postoperatively, on days 0–3, her examination was consistent with unresponsive wakefulness syndrome, unable to follow commands but able to intrmittently open her eyes and able to withdraw from pain in all extremities. Her tone and brainstem reflexes were normal, including intact pupillary response to light.

Her day 0–1 continuous video electroencephalogram (EEG) recorded a background of mixed delta, beta, and lower theta range activity, indicative of diffuse nonspecific cortical dysfunction, and focal slowing suggesting underlying structural or functional abnormality involving white matter, but it did not record electrographic or clinical seizures, off seizure medication. Her postoperative day 0 MRI (Figure 1) showed stabilization of the effects of increased intracranial pressure with its prior impact on cerebellar and cerebral ischemia and POUNCE.

By day 4, she remained in unresponsive wakefulness but was extubated. Due to her lack of clinical progression, a repeat MRI with resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) was performed (Figure 1) and showed seizure networks. Thus she received levetiracetam on days 6–35. She received melatonin for sleep rehabilitation on day 5 and was weaned from dexmedetomidine by day 6. Gabapentin and clonidine were started for agitation on day 8 and amantadine for wakefulness on day 9. By day 15, she had intermittent spontaneous nonreflexive and purposeful movements in all four extremities, indicative of minimally conscious syndrome. After extra ventricular drain removal on day 28, she developed a fever; cerebral spinal fluid cultures grew Candida tropicalis, for which she received antifungal therapy. A repeat MRI on day 28 revealed reduced swelling (Figure 1). At six months, a pediatric neurologist concluded that she was developmentally on track with motor, social, and self-care skills and had low normal language capacity.

rs-fMRI

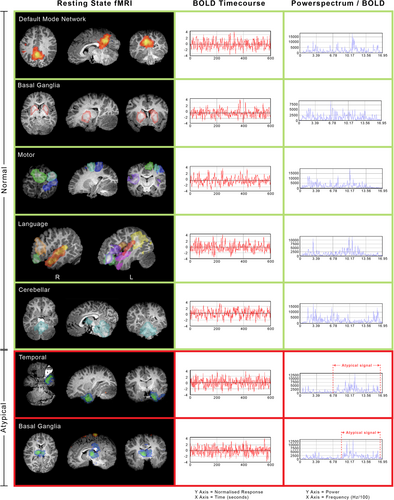

At the local institution, rs-fMRI is obtained as a component of the multimodal standard evaluation in acute brain injury after initial stabilization to assist with understanding the impact on whole brain networks and neuroprognostication, as suggested in the 2018 American Academy of Neurology disorder of consiousness guidelines and the 2020 European Academy of Neurology disorder of consciousness guidelines.2, 3

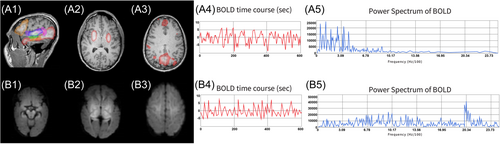

This patient's rs-fMRI findings were compared with age-reported norms contrasted against acute brain injury in children as described in Figure 2, which were in line with prior reports.4-10 Overall, the resting-state networks, including the cortical motor, language, and default mode networks, and the subcortical basal ganglia were detected with mild atypical features (Figure 3) that, when compared with a study in acute brain injury of neonates, portend good language and motor outcomes.6, 11

However, atypical networks were also detected, including in the (1) bilateral medial thalamus deactivation and increased blood oxygen level–dependent signal frequency, (2) bilateral cerebellum, posterior brainstem, and thalamus with relative deactivation and increased network blood oxygen level–dependent frequency, (3) seizure networks in the cortical fronto temporal regions, and (4) relative lack of detected long-range association fronto temporal-parietal network.

Patient 2 description

An 11-month-old term boy, born with neonatal abstinence syndrome, failure to thrive, and reflux, presented unresponsive to the emergency department. The emergency services personnel reported he was found cyanotic, bradypneic, and hypoxemic after co-sleeping with a parent. On arrival, he was in respiratory distress with a pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale of 10. He was initially hypotonic but then developed hypertonia and ankle clonus. He had small but reactive pupils and was minimally unresponsive. After receiving naloxone, he responded to noxious stimuli and had spontaneous movements. Initial lab work included complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, respiratory virus panel, blood culture, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin, which were all unremarkable. The urine toxicology screen revealed presence of cocaine metabolites. Head CT showed symmetric hypoattenuation and loss of gray-white matter differentiation of the cerebellar hemispheres as well as enlargement of the cerebellar hemispheres with effacement of fourth ventricle concerning for cerebral edema.

He was started on naloxone continuous infusion and admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for management of presumed opioid toxicity, although the extended urine drug screen was pending. Due to persistently altered mental status and poor respiratory effort, the patient was intubated and neurosurgery was consulted. Ventricular puncture was performed, and 10 mL of cerebrospinal fluid was sent for inflammatory and infection studies; both were unremarkable. Based on his imaging, reactive pupils, and responsiveness to noxious stimuli, the decision was made to continue to monitor him clinically and consider placing an extra ventricular drain if his condition deteriorated. He ultimately did not require surgical intervention and became increasingly awake and agitated within 12 h of admission.

His brain MRI withmagnetic resonance angiography on day 1 showed bilateral, nearly symmetrical T2/FLAIR hyperintense signal abnormality and cytotoxic edema in both posterolateral cerebellar hemispheres with corresponding diffusion restriction and reduced perfusion (Figure 4). There was also surrounding mass effect on the fourth ventricle with early obstructive hydrocephalus and tonsillar displacement below the foramen magnum. The patient was extubated on day 4 and began physical, occupational, and speech therapies. Repeat imaging on day 5 showed diminishing mass effect. Neurological examination revealed truncal ataxia and hyperreflexia. Although he participated in therapies, he had a flat affect and did not cry or fuss when left alone in the crib.

By hospital day 15, his neurological examination had improved tremendously, and he was smiling, playing, and interacting with providers as expected for his age. His muscle tone improved, and he was moving all extremities spontaneously, transferring toys, and clapping. On discharge, he had minimal ataxia but persistent clonus and hyperreflexia. The extended urine drug screen ultimately returned positive for fentanyl and norfentanyl, presumably due to co-ingestion of cocaine and fentanyl.

Outcome

The patient did not require inpatient rehabilitation and was discharged to foster care with outpatient therapies. By two months after hospital discharge, he had returned to his neurological baseline and had gained new developmental skills, such as feeding himself, walking, and beginning to speak. He was alert, smiling, and babbling and had normal muscle tone and strength throughout. He had brisk patellar reflexes with crossed adductors, but ankle clonus was no longer present. He walked with a toddler gait but did not appear ataxic.

Discussion

The pediatric mortality rate from all opioids tripled from 1996 to 201612 and from fentanyl increased 37-fold between 2013 and 2021.13 For those under 6 years, ingestion of both prescription and illicit sources from caretakers has been reported.14 Wolters et al. first described opioid-induced neurological complications in 1982. While most opioid-associated fatalities are generally attributed to respiratory depression, the potential resulting pathology can be due to specific-location neurotoxicity.15 Singh described delineating between respiratory and neurotoxicity etiologies based on the opioid formulation, route of administration, and age at exposure. For example, the adult-centric chasing the dragon syndrome combines opioid inhalation–induced temporal lobe epilepsy with cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, dementia, and coma.16 Transient cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei edema with restricted diffusion includes cytotoxic edema and reduced consciousness also impacting the cerebellar cortex, but more uniquely the hippocampi.17, 18 Intravenous heroin abuse, however, is associated with a broader impact from hypoxic-ischemic leukoencephalopathy.16

In pediatric patients, in contrast, POUNCE is not associated with a specific opioid formulation or delivery route but results in cerebellar edema. For example, POUNCE after a pediatric transdermal fentanyl patch exposure required a decompressive craniectomy.19 Like other opioid-related cerebellar toxic leukoencephalopathies, POUNCE also results in reduced consciousness, ataxia, and coma and can progress to death without intervention.1, 20, 21 Cerebellar edema and reduced mental status are the hallmarks of the syndrome.1 The T2-weighted symmetric white matter cerebellar hyperintensities distinguish POUNCE from other opioid neurotoxic conditions such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.1, 16, 20, 21

There is a paucity of POUNCE studies to guide management.1 Regarding surgical management beyond extra ventricular drain for intracranial pressure monitoring, Reisner et al. described a 2-year-old with lethargy and seizures who had posterior fossa decompression and cerebral spinal fluid drainage.20 Unlike our patient, he also required a partial cerebellectomy and had a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt placed after extra ventricular drain removal.20 In 2015, Duran et al. reported “malignant cerebellar edema” in two toddlers after accidental ingestion of prescription opioids. In these patients, the distinctive cerebellar edema and hyperintensities on CT and MRI were appreciated, and both patients had a similar hospital course to our patient with suboccipital craniectomy, cervical level one laminectomy, and extra ventricular drain placement.21 In our patient, we posit the irreversible cerebellar lesions were at least in part due to increased intracranial pressure with mass effect, most prominent in the infratentorial space, resulting in bilateral watershed ischemic cerebellar infarctions in addition to and as a result of the leukoencephalopathy. We suspect that the degree of recovery in our patient was related to the timing of intervention after presentation, as in a prior report.19

This is also the first documented use of rs-fMRI in POUNCE, especially in the acute phase during suppression of consciousness. The atypical networks have neuropathological underpinnings consistent with the regional network functions and implications for management. The atypical network in the medial thalamus is known to support consciousness in children, thus reduced connectivity in this region may be one of the factors reducing consciousness at the time of the scan.7 The network findings in the cerebellum, posterior brainstem, and thalamus are hypothesized to be related to potentially reversible aspects of the toxic leukoencephalopathy impacting the ascending communication between the cerebellum and the thalamus, which itself may also reduce consciousness.

In patient 1 neither the exam nor the EEG showed seizures. Regarding those who have neither clinical or electrographic seizures or interictal continuum, in traumatic brain injury professional society recommendations point toward giving prophylactic antiseizure medication.22 In contrast, we do not have such recommendations for patients with nontraumatic brain injuries such as POUNCE, as many sources point toward possible harm from prophylactic antiseizure therapy.23, 24 As the EEG was negative for seizure and interictal continuum, we did not have objective evidence for starting prophylactic antiseizure medications. However, in this situation of ongoing suppressed consciousness with no EEG correlate to direct therapy, the concept of using rs-fMRI is relatively new and not as well established as using rs-fMRI to classify disorders of consciousness and predict outcome from acute brain injury, both of which are supported by professional society recommendations and a meta-analysis.25 This concept was first posited by Bagshaw et al., who hypothesized that such network activity suppresses consciousness.26 In epilepsy, simultaneous fMRI-EEG has shown that the paroxysmal generalized discharges suppressing consciousness correspond to fMRI connectivity changes in regions supporting consciousness.27

In the intensive care unit population, rs-fMRI seizure networks in acute brain insult have been shown to predict epilepsy and thus are implicated in the patterns of damage resulting in future seizures.11 More specifically, reports have shown rs-fMRI to be a biomarker of treatable network pathology in acute brain insult responding to antiseizure medication.28, 29 The underlying reasoning is that rs-fMRI does not have the spatial limitations plaguing surface EEG and can therefore identify deeper regions involved in epileptogenesis that may not manifest observable clinical signs and may not be detectable through surface recording EEG electrodes.28, 30-33 Thus, in case-by-case clinical care directed by the clinicians' best judgment for the patient's well-being, wherein we are acquiring rs-fMRI for neuroprognostication per the American Academy of Neurology and European Academy of Neurology disorder of consciousness guidelines, it is reasonable to also consider treating the seizure networks if the patient is not otherwise clearly improving, as this is a population with high mortality.7, 25, 34

The seizure networks in the cortical fronto temporal regions of our patient resembled those reported in studies of drug-resistant epilepsy and case series in children, which when treated were reversible.4, 8, 11, 30, 35-38 These reports influenced the care and provider escalation of antiseizure medication in this child, with parent and team clearly understanding the level of evidence. Finally, the relative lack of detection of the long-range-association fronto temporal-parietal network is hypothesized to be a downstream impact of the regional seizure networks, suggesting potential for future improvement with resolution after seizure network therapy.

Conclusion

Though relatively uncommon, leukoencephalopathy due to opioid toxicity appears to be increasing in the pediatric population due to the opioid crisis. These cases in the context of the 2023 Child Neurology Society Neurocritical Care Special Interest Group discussion on opioid crisis cases highlight the increasing need for concerted collaborative multidisciplinary communication for rapid diagnosis of POUNCE, and potentially devastating effects need to be recognized by providers to ensure swift intervention and optimal outcome. Continued research is needed to further understand POUNCE and how it may differ from similarly presenting opioid-induced syndromes in children. Yet, having such severe cases with favorable outcomes demonstrates the potential for excellent medical and surgical management, assisted by standard and functional imaging and with consistent follow-up, to help guide our understanding of POUNCE and ways to optimize care, neuroprognostication, and recovery.

Author Contributions

Varina L. Boerwinkle: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Imani H. Sweatt: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Aniela Grzezulkowska: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. William R. Reuther: Data curation; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Aaron Gelinne: Conceptualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Emilio G. Cediel: Visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Divakar S. Mithal: Conceptualization; data curation; project administration; supervision; writing—review and editing. Carolyn S. Quinsey: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Scott W. Elton: Conceptualization; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.