Histopathology of granulomatous liver disease

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Watch a video presentation of this article

Abbreviations

-

- DILI

-

- drug-induced liver injury

-

- PBC

-

- primary biliary cholangitis

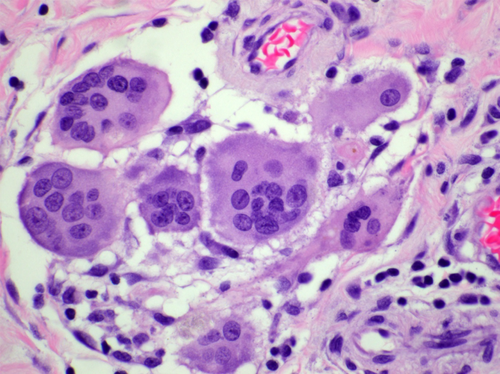

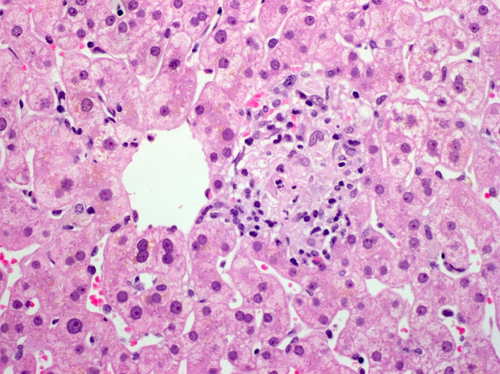

A granuloma is a collection of specialized tissue macrophages known as histiocytes. There is often a lymphocytic component, either intermingled with or forming a cuff around the histiocytes, but it is the aggregation of macrophages that is required to classify an inflammatory process as granulomatous. From a morphological standpoint, granulomas may be either loose or well-formed (epithelioid) and caseating or noncaseating. Sometimes the constituent histiocytes will fuse together forming multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 1).

Granulomas are relatively common in liver samples, identified in 2% to 10% of cases.1 Clinically, they may be restricted to the liver or reflect hepatic involvement by a systemic process. Histologically, they may be seen in the portal tracts, hepatic lobules, or both; there may be no accompanying inflammation (bland granulomas) or an associated lobular inflammatory infiltrate (granulomatous hepatitis). The location and type of granuloma(s), background changes within the liver, and the presence or absence of systemic involvement help provide clues to the diagnosis. Clinical diseases associated with hepatic granulomas are listed in Table 1.1-5 The most common etiologies will be discussed briefly in the following sections.

| PBC |

| Sarcoidosis |

| DILI |

| Infection (bacterial, viral, parasitic, fungal) |

| Histoplasma, Mtb, MAI, hepatitis C, Schistosoma |

| Malignancy |

| Lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| Toxin exposure/foreign body |

| Lipogranuloma |

| Idiopathic |

Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is an autoimmune condition that targets the small, intrahepatic bile ducts.6 The florid duct lesion, initially designated chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis, is the pathological hallmark.7 Granulomas are a requisite component of the florid duct lesion. Although they may rarely be epithelioid, a more typical appearance is that of a loose collection of histiocytes surrounding an injured bile duct (Fig. 2). There is disruption of the bile duct basement membrane and infiltration by lymphocytes. Presence of florid duct lesions varies with the stage of the disease. They are more common early in the course and diminish in frequency as PBC progresses and burns out.

Sarcoidosis

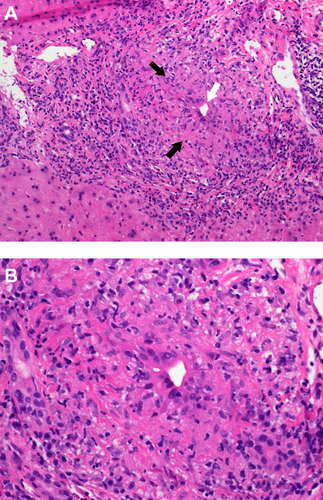

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem condition of unknown etiology thought to represent a reaction to one or more antigens. Worldwide prevalence is 2 to 60/100,000 people.8 It is defined by the presence of noncaseating epithelioid granulomas in affected organs or sites. Most frequent sites of involvement are the lung (>90%), lymph nodes, and liver.9 Although liver involvement is common (50%-70% of sarcoid livers histologically contain granulomas), only 20% to 40% of patients will have elevated LFTs.5 Less than 20% of patients will have clinically significant liver disease.8

Noncaseating epithelioid granulomas are present in both the portal tracts and hepatic lobules (Fig. 3). Roughly one-third of liver biopsies of hepatic sarcoidosis may have changes similar to those of PBC (19%) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (13%).4 However, in the majority of cases, the granulomatous infiltrates of PBC and sarcoidosis are sufficiently different to allow one to distinguish them. Sarcoid granulomas are typically larger, more numerous, better defined, not directed at the bile duct, and often associated with multinucleated giant cells. The granulomas may even coalesce to form tumefactive nodules occupying >90% of the tissue sample in a small number (6%) of cases.4 These may be mistaken for neoplasms by imaging. One never encounters this degree of granulomatous inflammation in PBC. Table 2 outlines the pathological and clinical features that are helpful in distinguishing sarcoidosis from PBC. Sarcoid granulomas are associated with end-stage fibrosis (cirrhosis) in only 6% to 8% of patients.4, 8 Vascular abnormalities, including portal hypertension (with or without cirrhosis) and Budd-Chiari syndrome, are rare but do occasionally occur.5

| Diagnosis | Granuloma Location | Bile Duct Destruction | Granuloma Type | Confluent Granulomas | Giant Cells | AMA | Systemic Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBC | Portal based | Present | Poorly formed | Absent | Absent to rare | Positive | Absent |

| Sarcoidosis | Portal and lobular | Absent to rare | Well formed | Occasional | Common | Negative | Present |

Infection

A variety of bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic organisms may induce a granulomatous reaction in the liver. A comprehensive review of infectious granulomas of the liver is beyond the scope of this article. Interested readers should see Lamps1 for a thorough and authoritative review.

From a practical, clinical perspective, special stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungal organisms (GMS or periodic acid–Schiff) are performed anytime a newly diagnosed granulomatous process is encountered in the liver. Sequential biopsies for previously diagnosed conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis, Crohn's disease, or PBC) would not require special stains.

Granulomas with central, caseating necrosis are considered infectious until proven otherwise. As detailed earlier, conditions such as PBC and sarcoidosis are not associated with caseating necrosis (sarcoid granulomas may rarely contain fibrinoid necrosis). Unfortunately, histochemical stains lack sensitivity, so a negative result does not preclude an infectious process.

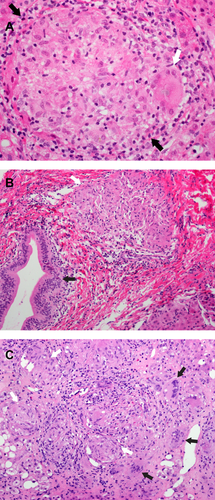

Drug-Induced Liver Injury

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) most commonly manifests histologically as cholestasis.10 Granulomas may be identified in a minority of cases. One study demonstrated granulomatous hepatitis in 3.6% (4/110) of patients with documented DILI.10 Granulomas are not tumefactive (as seen in sarcoidosis) or typically directed at the bile ducts (as seen in PBC). Instead, they are usually small (Fig. 4) and present within the hepatic lobule, accompanied by a portal and lobular inflammatory infiltrate (i.e. granulomatous hepatitis). Eosinophils are typically present. Numerous drugs and medications have been implicated in granulomatous DILI, with the most common being antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic agents, antituberculous medications, and antiepileptics.10, 11

Lipogranuloma

The lipogranuloma is a special type of granuloma composed of lipid-containing macrophages with associated lymphocytes. Initial studies suggested that these formed as a reaction to mineral oil in some foods and medications. However, it has subsequently been demonstrated that they may also form when histiocytes ingest fat droplets released by ruptured hepatocytes in the setting of fatty liver disease.12