Ping-pong snaring of a totally dislodged stent across left main ostium: “All is not lost”

Abstract

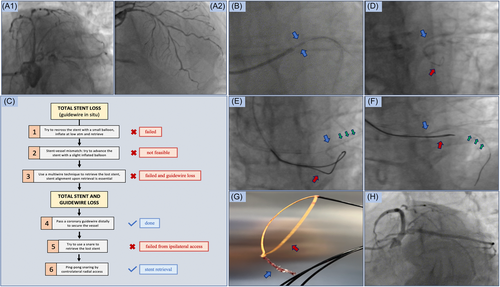

Undeployed stent loss is a rare but potentially serious complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. Its management is not assisted by well-defined guidelines, and it is made even more difficult when the dislodged stent is not protected by in situ guidewire. In this work, we present the case of a total stent loss with a crushed device protruding out of the left main. In this hopeless circumstance, an innovative ping-pong technique was used to contralaterally perform a successful stent retrieval.

1 INTRODUCTION

Stent loss is a rare complication of percutaneous coronary intervention, more frequently occurring when dealing with heavily calcified lesions.1, 2 The device retrieval is usually preferred to stent crushing and abandoning, and it is highly recommended when the undeployed stent is located in the proximal part of the coronary arterial tree.3, 4 However, dislodged stent requires cautious management, as retrieval failure may ultimately lead to serious consequences, such as vessel dissection, coronary perforation, and systemic embolization.

1.1 Case report

A 79-year-old man with inferior-posterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction was referred to our cathlab. Coronary angiography documented three-vessel disease with acute proximal left circumflex artery (LCX) occlusion, diffuse and heavily calcified left anterior descending artery (LAD), and mid right coronary artery critical stenosis (Figure 1A.1,A.2 and Supporting Information: Video S1). Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on LCX was performed, but patient still complained chest pain. Therefore, we proceeded with PCI on LAD. After vessel preparation, including the use of rotational atherectomy (Supporting Information: Video S2), an attempt to advance a 2.25 × 18 mm drug-eluting stent (DES) in first diagonal branch failed. At shaft retrieval, the stent was not over the balloon anymore, being lost at proximal left main stem (Figure 1B).

- 1.

re-crossing the stent with a 1.25 mm balloon failed;

- 2.

the high amount of calcium in the LAD made it unfeasible to advance the lost stent distally, using the balloon as a pushing device;

- 3.

considering the stent location in left main, a crushing bailout strategy was not ideal;

- 4.

therefore, the guidewires were twisted to entangle the stent and then retracted.

- 1.

once the vessel was secured with a new guidewire, ipsilateral snaring attempts both with a 4.0 and 30 mm Goose Neck snares (Medtronic) were ineffective, mainly due to the absence of devices coaxiality (Figure 1D and Video S3);

- 2.

contralateral radial access was gained and the 30 mm snare catheter was advanced into a 7-Fr JL3.5 guiding catheter (Cordis) to perform snaring in a ping-pong fashion;

- 3.

in fact, to improve the suboptimal device alignment (Figure 1E and Supporting Information: Video S4), a ping-pong wiring of LAD was performed to stabilize and to orient the catheter with the lost stent (Figure 1F);

- 4.

finally, a safe snaring of the dislodged stent was accomplished (Figure 1G and Supporting Information: Video S5).

PCI was completed by implanting three DES across the left main-LAD axis, thus reaching a satisfying angiographic result (Figure 1H and Supporting Information: Video S6). The patient was then transferred to cardiac intensive care unit for continuous monitoring. After revascularization completion with PCI on right coronary artery, he was dismissed in optimal clinical condition.

2 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a ping-pong technique-assisted retrieval of an undeployed stent protruding out of the left main.

Total stent loss is a rare but potentially serious PCI complication. An appropriate management needs accurate evaluation of lost stent position and condition, and may benefit from intracoronary imaging if fluoroscopy is not diagnostic.5 Intracoronary imaging, mainly intravascular ultrasound, should always be considered to check coronary vessel integrity after crushed stent retrieval. However, in our case, the absence of both angiographic and clinical suspect of left main damage supported our choice to avoid further manipulation of the left coronary artery and clinically monitor the patient in cardiac intensive care unit.

The contemporary loss of in situ guidewire makes the retrieval highly challenging. Our case emphasized the risk of the “twirling guidewires” technique, as our choice to twist and retract the guidewires in the attempt to capture the stent, eventually turned a difficult scenario into a nightmare. Therefore, snaring devices should be considered as first option to retrieve a dislodged stent when it is still protected by its guidewire. With regard to the sizing of the snaring device, in our experience a large snare, by gently surrounding the undeployed device, can reduce the risk of further stent manipulation, embolization, or vessel injury.

The embolization risk of lost stent located in the ostial part of coronary arteries is not negligible. A perfect alignment of the snaring devices with the lost stent is crucial to minimize this possibility, and may require a contralateral access approach.

3 CONCLUSION

Total stent dislodgement is a highly threatening scenario, whose management needs careful maneuvers.

Snaring devices should be preferred over guidewires twirling to reduce the risk of in situ guidewire loss.

Ping-pong wiring can improve the stability and the maneuverability of the devices, and gaining contralateral access seems a valid option to grant a safer snaring of a lost stent prolapsing from the left main.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Matteo Saccocci, Dr. Michele Bellamoli, and Dr. Luca Bettari for their contribution to this case.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.