Tumor microenvironment signaling and therapeutics in cancer progression

Anshika Goenka, Fatima Khan, Bhupender Verma and Priyanka Sinha contributed equally to this work

Abstract

Tumor development and metastasis are facilitated by the complex interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironment, which comprises stromal cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, among other factors. Stromal cells can adopt new phenotypes to promote tumor cell invasion. A deep understanding of the signaling pathways involved in cell-to-cell and cell-to-ECM interactions is needed to design effective intervention strategies that might interrupt these interactions. In this review, we describe the tumor microenvironment (TME) components and associated therapeutics. We discuss the clinical advances in the prevalent and newly discovered signaling pathways in the TME, the immune checkpoints and immunosuppressive chemokines, and currently used inhibitors targeting these pathways. These include both intrinsic and non-autonomous tumor cell signaling pathways in the TME: protein kinase C (PKC) signaling, Notch, and transforming growth factor (TGF-β) signaling, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress response, lactate signaling, Metabolic reprogramming, cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS)–stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and Siglec signaling pathways. We also discuss the recent advances in Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 (PD-1), Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4 (CTLA4), T-cell immunoglobulin mucin-3 (TIM-3) and Lymphocyte Activating Gene 3 (LAG3) immune checkpoint inhibitors along with the C-C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4)- C-C class chemokines 22 (CCL22)/ and 17 (CCL17), C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2)- chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5)- chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (CCL3) chemokine signaling axis in the TME. In addition, this review provides a holistic understanding of the TME as we discuss the three-dimensional and microfluidic models of the TME, which are believed to recapitulate the original characteristics of the patient tumor and hence may be used as a platform to study new mechanisms and screen for various anti-cancer therapies. We further discuss the systemic influences of gut microbiota in TME reprogramming and treatment response. Overall, this review provides a comprehensive analysis of the diverse and most critical signaling pathways in the TME, highlighting the associated newest and critical preclinical and clinical studies along with their underlying biology. We highlight the importance of the most recent technologies of microfluidics and lab-on-chip models for TME research and also present an overview of extrinsic factors, such as the inhabitant human microbiome, which have the potential to modulate TME biology and drug responses.

Abbreviations

-

- TME

-

- tumor microenvironment

-

- ECM

-

- extracellular matrix

-

- MMP

-

- matrix metalloproteinase

-

- TAM

-

- tumor-associated macrophage

-

- CAF

-

- cancer-associated fibroblast

-

- APC

-

- antigen-presenting cell

-

- DC

-

- dendritic cell

-

- Teff

-

- effector T cell

-

- NK

-

- natural Killer cell

-

- XCL

-

- X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand

-

- CCL

-

- CC motif chemokine ligand

-

- FLT3LG

-

- FMS Related Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 3 Ligand

-

- FGF

-

- fibroblast growth factor

-

- CXCL

-

- CXC motif chemokine ligand

-

- VEGF

-

- vascular endothelial growth factor

-

- SDF-1

-

- stromal cell-derived factor 1

-

- TGF-ß

-

- transforming growth factor ß

-

- IL

-

- interleukin

-

- IDO

-

- indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

-

- TDO2

-

- tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase

-

- SLIT2

-

- slit guidance ligand 2

-

- CD

-

- cluster of differentiation

-

- PDGF

-

- platelet-derived growth factor

-

- PDGFR

-

- platelet-derived growth factor receptor

-

- HGF

-

- hepatocyte growth factor

-

- MET

-

- mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor

-

- EC

-

- Endothelial cell

-

- CAR-T Cell

-

- Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell

-

- PSMA

-

- prostate-specific membrane antigen

-

- TNF α

-

- tumor necrosis factor α

-

- NICD

-

- notch-intracellular domain

-

- ASO

-

- antisense oligonucleotides

-

- BiP

-

- binding-immunoglobulin protein

-

- HIF

-

- hypoxia-inducible factor

-

- PD-1

-

- Programmed cell death protein 1

-

- PD-L1

-

- Programmed cell death protein ligand 1

-

- CCR

-

- C-C chemokine receptor type

-

- 3D

-

- Three (3D)-dimensional

-

- PDX

-

- patient-derived tumor xenograft

-

- WNT

-

- Wingless/Integrated

-

- PKC

-

- protein kinase C

-

- ER

-

- Endoplasmic Reticulum

-

- cGAS

-

- cyclic GMP–AMP synthase

-

- STING

-

- stimulator of interferon genes

-

- CTLA4

-

- Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4

-

- TIM-3

-

- T-cell immunoglobulin mucin-3

-

- LAG3

-

- Lymphocyte Activating 3

-

- PAK4

-

- p21-Activated kinase 4

-

- EGFRvIII

-

- Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III

-

- FGF

-

- Fibroblast growth factor

-

- PEGPH20

-

- pegvorhyaluronidase alfa

-

- DON

-

- 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine

-

- GM-CSF

-

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

-

- Th

-

- T helper

-

- Teff

-

- T effector

-

- HOX

-

- Homeobox

-

- DAG

-

- diacylglycerol

-

- STAT

-

- Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription

-

- NF-κB

-

- Nuclear factor-κB

-

- DLL1

-

- delta like canonical Notch ligand 1

-

- JAG2

-

- jagged canonical Notch ligand 2

-

- NICD

-

- intracellular domain of the Notch receptor

-

- ADC

-

- antibody-drug conjugates

-

- IRE1α

-

- inositol-requiring enzyme 1α

-

- SLC16A

-

- solute carrier family 16 member

-

- LDHA

-

- lactate dehydrogenase A

-

- CHC

-

- cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate

-

- ROS

-

- Reactive Oxygen Species

-

- IDH

-

- Isocitrate dehydrogenase

-

- D2HG

-

- D-2-Hydroxyglutarate

-

- GBM

-

- Glioblastoma

-

- AML

-

- Acute myeloid leukemia

-

- TCGA

-

- The Cancer Genome Atlas

-

- TMEM

-

- transmembrane protein 173

-

- TBK-1

-

- TANK-binding kinase 1

-

- IRF-3

-

- Interferon regulatory factor 3

-

- PCDH

-

- protocadherin

-

- Cx

-

- connexin 43

-

- IKK

-

- nuclear factor-κB (IκB) kinase

-

- IFN-I

-

- Type I interferons

-

- MDSC

-

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

-

- BTLA

-

- B and T lymphocyte attenuator

-

- scRNA-seq

-

- single-cell RNA sequencing

-

- EVs

-

- extracellular vesicles

-

- ITSM

-

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif

-

- NSCLC

-

- Non-small cell lung cancer

-

- SHP2

-

- Src-homology-region-2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2

-

- CyTOF

-

- Cytometry by time of flight

-

- TCR

-

- T cell receptor

-

- CTLA4

-

- Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

-

- JNK

-

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

-

- ERK

-

- extracellular signal-regulated 701 kinases

-

- TIM-3

-

- T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

-

- HLA-B

-

- human 710 leukocyte antigen B

-

- LCK

-

- lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase

-

- ITK

-

- inducible T cell kinase

-

- LAG3

-

- Lymphocyte activation gene 3

-

- α-syn

-

- α-synuclein fibrils

-

- L-SECtin

-

- lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cell C-type lectin

-

- FGL-1

-

- fibrinogen-like protein 1

-

- TILs

-

- tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

-

- BTLA

-

- B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator

-

- HVEM

-

- herpesvirus entry mediator

-

- HNSCCs

-

- head and neck squamous cell carcinomas

-

- MDSCs

-

- myeloid-derived suppressive cells

-

- PDOs

-

- patient-derived organoids.

1 BACKGROUND

The concept of tumor microenvironment (TME) research emerged in the 1800s when the relationship between inflammation and cancer was proposed and acknowledged with Paget's theory of “seed and soil” [1]. With the progress made in the following decades, Hanahan and Weinberg enhanced the hallmarks of cancer from six to ten in 2011 with the recognition of the TME [2]. However, with the limited understanding of the TME, the therapies targeted against its components, such as the blood vasculature, were efficient against cancers of all organs regardless of their source [3].

With the advent of single-cell analysis through sequencing technologies and analytical bioinformatics, the immense complexity of the TME is apparent, and contrary to the earlier notions, the TME is now understood to be either tumor-supportive or tumor-suppressive depending on the stage and type of cancer [4, 5]. Currently approved therapeutics of the TME are targeted against immune checkpoints, T cells and blood vasculature. In one study, inhibition of p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4), selectively expressed by tumor endothelial cells (ECs) in glioma, re-sensitizes tumor cells to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy engineered against epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) mutation in glioma, allowing engineered T cells to enter the brain and elicit a robust immune response [6]. Another study targeting chemoresistant and desmoplastic colorectal cancer (CRC) cells by targeting vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and angiopoietin-2 (ANGPT2) along with the cluster of differentiation 40 (CD40) agonistic antibodies destroyed tumor fibrosis and induced T cell-mediated killing [7]. These studies exemplify the successes and current state of the art of TME signaling and mechanisms of unleashing tumor therapeutics.

However, several challenges impede the progression of TME research. One challenge is to create experimental models that can preserve the initial characteristics of the primary tumor to develop personalized medicine tools for drug development and cancer therapy. The recent development of three-dimensional platforms for cell culture using lab-on-chip and microfluidic devices holds enormous potential to better simulate TME processes and bridge the gap between preclinical and clinical translations [8]. Another aspect of personalized medicine that poses a challenge to TME research is to identify responders from non-responders [4]. To achieve this, several approaches, such as noninvasive liquid biopsies to identify circulating tumor DNA in the blood or the use of extracellular vesicles as diagnostic markers, are underway to improve the prediction of responses in patients [9]. Thus, preclinical studies, especially those involving immune responses, should consider responsiveness of the mechanistic aspects of mutations or molecular subtyping in patients.

Few recent reviews have discussed the advances in TME therapeutics. Baghban et al. explored the molecular interactions between cancer cells and the TME to identify novel cancer therapeutics [10]. Jin et al. classified the chemopathological characteristics of TME, such as the metabolic, immune and acidic niches and advances in drug repurposing in their context [11]. Moreover, Bejarano et al. provided a comprehensive analysis of the current therapies targeting the TME and their clinical evaluation [3]. In this current review, we extensively discuss the advances in the signaling mechanisms, both intrinsic to cancer cells and non-autonomous signaling prevalent in the TME and the therapeutics targeting those mechanisms from a preclinical and clinical perspective. We further comprehensively assessed the prevalent and newly identified tumor models in TME research and described how the gut microbiome alters the TME and affects treatment response.

2 EXPLOITING MICROENVIRONMENTAL CUES FOR THERAPY

2.1 Components of the TME

Single-cell-based technologies have enabled a better dissection of the TME through precise monitoring of cell sub-populations and spatial architecture, thus revealing the heterogeneous and complex nature of the TME [10, 12]. Other than the cancer cells that form the bulk of the tumor, the other predominant populations include the immune cells constituting the tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), natural killer (NK) and dendritic cells (DCs), and T and B lymphocytes. The blood and lymphatic ECs, complex collagen fibers and glycoproteins form the ECM, while the cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and mesenchymal stem cells further assist in ECM remodeling and even chemoresistance [13, 14]. The unique signatures of its cellular components, the associated signaling and the diversity of the TME have been targeted in cancer therapy.

The contribution of the immune system in the modulation of cancer has recently gained importance. Other than tumor heterogeneity, the ‘immune system’ forms a crucial aspect of the complex architecture of the TME, and their modulation can be leveraged to overcome the persistent problems of therapy failure and resistance. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells infiltrate in the TME to get primed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), macrophages, B cells and DCs to modulate cytotoxic effector T (Teff) cell response. For instance, DCs secrete the chemoattractants chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 (CXCL9) and 10 (CXCL10) to facilitate the infiltration of CD8+ Teff cells in the TME and for T cell cytotoxic activity [15]. Instead, their engagement in inhibitory crosstalk, such as with the PD-1/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) signaling axis, leads to immunosuppression in the TME [16]. Other immune cells facilitating a pro-tumorigenic response in the TME include the immunomodulatory regulatory T (Treg) cells and the myeloid suppressor (MDSCs) that result in an immunosuppressive TME [17] and therapy failure. However, the presence of NK cells in the TME is believed to be anti-tumorigenic, resulting from the release of cytokines and chemoattractants such as X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (XCL1), chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) or Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3LG) and leading to APC accumulation in the TME [18-20].

CAFs were initially considered a homogeneous population. However, recent studies indicated that CAFs consist of several types of stromal cells that differ in their origin, functions, number, and phenotype [21-24]. Thus, CAFs can either lead to cancer progression or inhibit cancer growth, depending on their nature. They secrete several growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), to promote angiogenesis via the VEGF, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and TGF-ß signaling [25, 26]. CAFs recruit and polarize immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, T cells and DCs to a pro-tumorigenic phenotype by secreting several cytokines, chemokines, and other effector molecules such as Interleukin 6 (IL-6), and 8 (IL-8), TGF-β, CXCL12, CCL2, SDF-1, VEGF, Indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO2) [27]. However, certain CAFs (Slit Guidance Ligand 2 [Slit2]+ and cluster of differentiation 146 [CD146]+ CAFs) were shown to have anti-tumorigenic effects such as tumor suppression and increased tumor chemosensitivity [28]. Furthermore, downregulating the paracrine signaling of fibroblasts, such as the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)/ PDGF receptor (PDGFR) signaling pathway and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/ mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (MET) signaling pathway, was shown to promote chemosensitivity in CAFs [29, 30].

The TME modulates ECs to induce an angiogenic response because of the high nutritional demand of the tumor [31]. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) activation in tumor cells promotes the secretion of proangiogenic factors, such as VEGF, FGF-2, and PDGF, and stimulates angiogenesis [32, 33]. ECs are targeted indirectly for tumor therapy by inhibiting angiogenesis via neutralizing antibodies for VEGF or inhibitors of VEGF activity [34]. In a clinical trial, bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against circulating VEGF-A, combined with chemotherapy was shown to improve the overall and progression-free survival of colorectal cancer patients compared with chemotherapy alone [35]. However, tumor cells become resistant after long-term treatment, and these anti-angiogenic drugs were shown to promote vasoinvasion leading to metastasis and reduced lifespan in mice [36]. Thus, it suggests the need for targeting the multiple oncogenic interactions in the TME rather than individual cell types and molecules.

ECM acts as a scaffold and plays a tumor-suppressing role in healthy tissues; however, it is modified in tumor tissue to possess a tumor-promoting role [37]. The ECM components underlying tumor-promoting activity, such as fibronectin and its splice variants, crosslinked collagen I and tenascin-C, are induced in the TME [37, 38] and interact with integrins to influence tumor cell migration, proliferation and cellular signaling [39]. Various strategies have been developed to target aberrant ECM components to develop novel treatments, including fresolimumab (to inhibit collagen synthesis), collagenases and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (to promote collagen degradation), 4-methylumbelliferone (to inhibit hyaluronic acid synthesis), hyaluronidase (to promote hyaluronic acid degradation), Vitaxin and Volociximab (to target integrin and inhibit angiogenesis) [40]. Moreover, Provenzano et al. found that systemic administration of pegvorhyaluronidase alfa (PEGPH20), an enzyme against hyaluronic acid, reduced stromal hyaluronic acid, normalized interstitial fluid pressures, re-expanded the microvasculature and led to tumor suppression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas murine models [41].

Thus, different components of the TME secrete growth factors, components of the ECM, cytokines and extracellular molecules that are essential for signaling between cells in the TME and systemically. Thus, it would be critical to identify strategies for identifying key vulnerabilities and targeting them to alleviate the immune suppression prevalent in most TMEs.

2.2 TME-based cancer therapy

In recent times, combining therapies, especially those inducing the engagement of immune cells, have been the primary focus of TME-based therapeutics. In this section, we review several facets of the TME that have been targeted for therapy. Table 1 shows the clinical trials targeting different components of the TME.

| Inhibitor | Functional Mechanism | Cancer Type/Stage | Clinical ID/Phase | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECM | ||||

| Fresolimumab | mAb inhibits collagen synthesis (targets TGF-β) | Advanced malignant melanoma or renal cell carcinoma | NCT01401062NCT02581787 | [42] |

| Losartan | Anti-hypertensive drug: inhibits collagen synthesis | Breast, pancreatic, skin, and ovarian cancer | NCT01821729 | [43, 44] |

| FN-CH296 | Recombinant fibronectin - stimulates T cells to achieve strong tumor-inhibitory effects | Advanced cancer | Phase I | [45] |

| Vitaxin | Humanized mAb - targets integrin αvβ3 | Progressive tumors with stage IV disease | Phase I | [46] |

| Cilengitide | Peptide antagonist - targets the binding between integrin αvβ3 and RGD | Head and neck tumor, glioblastoma | Phase II | [42, 47] |

| huBC-1-mIL-12 | Murine mAb - targets extra domain B (EDB) of fibronectin | Malignant melanoma, renal cell carcinoma | NCT00625768 (Phase I) | [48] |

| L19-IL-2 | L19, was fused with IL-2 - targets EDB | Advanced renal cell carcinoma, metastatic melanoma | NCT01058538 (I) NCT01055522 (II) | [49, 50] |

| RO5429083 | CD44 antibody - inhibits the mRNA transcription of CD44 or CD44v | Neoplasms, Myelogenous Leukemia, acute | NCT01358903NCT01641250 | [51, 52] |

| Ronespartat (SST0001) | Heparanase inhibitor | Multiple myeloma | NCT01764880 (Phase I) | [53, 54] |

| Incyclinide (CMT-3 and COL-3) | MMP inhibitor | Advanced carcinomas | NCT00004147NCT00003721NCT00001683NCT00020683 | - |

| Immune cells | ||||

| MTP10-HDL | Immunostimulatory muramyl tripeptide - epigenetic reprogramming of the multipotent progenitor cells in the bone marrow | Mouse melanoma model | preclinical | [55] |

| 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) | Blocks glutamine metabolism in myeloid precursor cells | 4T1 triple-negative breast cancer model | preclinical | [56] |

| “designer” T cells (dTc, CAR-T) against PSMA | PSA declines of 50% and 70% in 2/5 patients | Prostate cancer | phase I trial | [57] |

| CD133-CAR-T therapy | CART-133 transfer for treating patients with CD133-positive and late-stage metastasis malignancies. | Advanced metastasis malignancies | phase I trial | [58] |

| HPV16 vaccine (ISA101) | Long immunogenic peptide antigens - induce CD4+T and CD8+T cell cytotoxic activities | HPV16-induced cancers | Phase I/II study | [59] |

| Pexidartinib (PLX3397) | CSF-1R 1 inhibitor | Advanced solid tumors | NCT02734433 (1) | [60] |

| Giant cell tumor | NCT02371369 (3) | [61] | ||

| Melanoma | NCT02975700 (1/2) | - | ||

| Pancreatic/colorectal cancer | NCT02777710 (1) | - | ||

| Gastrointestinal stromal cancer | NCT03158103 (1) | [62] | ||

| Advanced solid tumors | NCT01525602 (1) | [63] | ||

| Gastric cancer | NCT03694977 (2) | - | ||

| Canakinumab | Anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody | Lung cancer | NCT01327846 | [64] |

| Sipuleucel-T | Recombinant fusion protein of prostatic acid phosphatase; PA2024 linked to GM-CSF | Prostate adenocarcinoma | NCT03686683 | - |

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts | ||||

| Val-boroPro (talabostat) and Cisplatin | FAP-targeted inhibitory small-molecules | Colorectal cancer, melanoma | Phase II | [65, 66] |

| Crenolanib | PDGFR-targeted inhibitor | Gastro-intestinal stromal tumor | NCT02847429 (Phase III) | - |

| Endothelial Cells and Pericytes | ||||

| Bevacizumab (Avastin) | Antibody - anti-angiogenic; targets VEGF | FDA-approved (in clinics) | [67] | |

| Everolimus (RAD001) | Rapamycin derivative mTOR inhibitor | Renal cell carcinoma | NCT01206764 (Phase 4) | - |

| Pazopanib (Votrient) | Multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Advanced renal cell carcinoma and soft tissue sarcoma | [68, 69] | |

Tumors have a high demand for rich vasculature to keep up with the high nutrient and glucose demand for their progression. However, most tumors are poorly vascularized and hypoxic, which advances cancer progression and chemoresistance [70, 71]. Additionally, poor tumor vasculature increases interstitial fluid pressure, protecting the tumor core from cancer therapeutics via the bloodstream [72, 73]. To block neoangiogenesis and mitigate hypoxia, VEGF antagonists have been used as a line of therapy [74]. However, its success depends on other microenvironmental factors. For example, anti-VEGF treatment is ineffective in obese mice due to increased IL-6 and FGF-2 expression by the adipocytes in the TME, while co-targeting these improve the anti-VEGF therapy response [75].

Tumor-specific ECM varies among different cancer types. This specificity is exploited for therapies. For example, breast cancer samples have a remarkably high fibrillar collagen content, leading to a poor prognosis [76, 77]. Thus, probes targeted to tumor-specific collagen help detect tumors and micrometastases [78]. Conjugation or recombinant fusion of therapeutic agents such as cetuximab or lumican to a collagen-binding domain peptide can increase efficacy and safety [79, 80]. Similar to collagen, TME also displays a unique matrix of fibrin and fibronectin. Specific antibodies (such as L19) against fibronectin to improve tumor response in the clinical trials of patients with glioblastoma by localizing interleukin 2 (IL-2) or interleukin 12 (IL-12) in the tumor, leading to increased infiltration of cytotoxic T cells [81-83].

The abundance of TAMs in TME can be therapeutically harnessed if they can be polarized to their anti-tumor phenotype. Histone deacetylase inhibitor, TMP195, polarizes TAMs toward an anti-tumor phenotype and increases the efficacy of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and anti-PD-1 therapies [84]. Moreover, the phagocytic role of TAMs can be harnessed to concentrate cytotoxic drugs in the TME [85, 86]. Miller et al. found a reduction in liver metastases due to enhanced delivery of nano-encapsulated platinum in the TME via TAMs in a breast cancer mouse model [87]. On a similar note, immunosuppressive myeloid cells can be differentiated/polarized for anti-tumor phenotypes [88, 89]. For this, myeloid progenitor differentiation has been manipulated via a bone marrow homing nanoparticle therapeutically containing the immunostimulatory muramyl tripeptide. This peptide shows anti-tumor effects by epigenetic reprograming of the multipotent progenitor cells in the bone marrow, which overcomes the immunosuppressive TME [55]. Moreover, a prodrug of 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) that blocks glutamine metabolism in myeloid precursor cells can differentiate monocytes into anti-tumor TAMs, leading to tumor regression in mouse models [56].

Stimulating a patient's dominant immune system can have long-lasting effects against cancer. Targeting the immunosuppressive TGF-β signaling in T cells by PLGA nanoparticles enhances antitumor immunity in mice. These nanoparticles bind to T cells and release a TGF-βR1 inhibitor, SD-208, that stimulates the potency of CD8+ Teff cells while inhibiting the inhibitory Treg cells in the TME [90]. CAR-T cell therapy by engineering T cells to express synthetic receptors that recognize tumor-associated antigens in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent way has shown huge success in hematological malignancies. Although CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors is challenging since CAR-T cells cannot penetrate solid tumors through vascular endothelium, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-directed CAR-T cells have shown success in clinical trials against prostate cancer [57]. CD133-CAR-T therapy in colorectal, pancreatic and hepatocellular carcinoma has shown anti-metastatic potential in a phase I clinical trial [91]. Moreover, therapeutic cancer vaccines have shown promising results in cancer immunotherapy by amplifying tumor-specific T-cell responses. They can be categorized as cellular, viral, or molecular vaccines [92]. Viral vaccines using a heterologous prime-boost strategy to amplify T-cell responses have been successful in prostate cancer. Here, the delivery of a tumor antigen by a viral vector is boosted by a subsequent delivery of the same antigen by another vector [93]. Also, peptide-based vaccines that deliver long immunogenic antigens to DCs have been shown to induce CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell cytotoxic activities and improve survival in patients with HPV-16-positive cervical cancer and newly diagnosed glioblastoma (NCT02455557) [59].

DCs form a nexus between the adaptive and innate immune responses. DCs present antigen to T cells along with upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules and cytokine production. The inactivity of DCs in the TME to perform these functions hampers immune response to tumors. DC deficiency in the TME can be caused by several factors. Tumor-derived exosomes are known to inhibit DC differentiation by releasing immunosuppressive factors such as IL-6 and TGF-β [94, 95]. Moreover, high lipid accumulation in DCs facilitated by tumor cells can also decrease the secretion profile and reduce antigen-presenting capacity, and high amounts of hyaluronic acid in the ECM affect DC maturation [96]. Also, hypoxia in the TME inhibits DC maturation and function by inducing VEGF signaling caused by the binding of hypoxia-induced VEGF to its receptors on DC membranes [97]. Combinational DC-based therapy, such as DC-based vaccine or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which stimulates DC differentiation, activation and migration, along with immune-checkpoint blockade, has shown success in clinics [98]. Immune checkpoint blockers pembrolizumab and nivolumab are among the most frequently used blockers, along with US FDA-approved PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [96].

CAFs are unique in expressing their cell surface markers. For example, depleting fibroblast activation protein (FAP)+ CAFs via a FAP vaccine decreases collagen density and improves chemoresistance in mouse models [99]. However, CAF depletion has also been shown to reduce infiltrating immune cells, leading to tumor progression [100]. CAF depletion in the TME leads to a shift from T helper 2 (Th2) to T helper 1 (Th1) to promote inflammation, accompanied by the up-regulation of IL-2 and IL-7 and downregulation of TAMs, Tregs and MDSCs [101]. Moreover, CAF depletion using diphtheria toxin-based immunotherapy reduced cancer growth by increasing CD8+ Teff-cell infiltration to the TME [102]. Another approach to target CAFs is to inhibit their tumor-promoting functions. For example, CAFs are known to activate the transcription of homeobox (HOX) transcript antisense RNA through paracrine TGF-β1, which leads to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and thus promotes breast cancer metastasis. Moreover, inhibiting TGF-β1 was found to significantly inhibit CAF-induced tumor growth and lung metastasis in an MDA-MB-231 orthotopic tumor transplantation nude mouse model [103]. Furthermore, inhibiting the proliferation of CAFs by co-administering IPI-926, which inhibits the hedgehog signaling, with the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine increasing tumor drug sensitivity in the mouse models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [104].

Most current therapies directed against the TME target TAMs, tumor vasculature, DCs, ECM, T cells and CAFs. As each of these cell types functions uniquely to modulate the TME, it is important to analyze them and identify critical nodes that could be targeted to inhibit TME support to tumor cells.

3 TARGETING SIGNALING IN THE TME

Tumor cells highjack and modulate various signaling pathways such as the PKC, Notch and TGF-β signaling pathways, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response, lactate and metabolic signaling, and the most recent cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS)–stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and Siglec signaling pathways [105-108]. These signaling pathways are crucial in maintaining a favorable TME and developing resistance against therapies or multi-drug resistance [109]. In this section, we review the signaling mechanisms of these pathways in different cancer types and the current status of therapies to target them.

3.1 Protein kinase C (PKC) signaling

The extent to which PKC isoform activation or inactivation affects TME components, including stroma and immune systems, determines their promotion or suppressor functions on tumor growth. PKC is a family of structurally related serine/threonine kinases that functions as the transducer of signals from a variety of molecules ranging from hormones (adrenaline, angiotensin), growth factors (insulin, epidermal growth factor), cytokines (Tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β and IL-6) and neurotransmitters (i.e., dopamine, endorphins) to regulate cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, adhesion and malignant transformation [105, 110, 111]. The binding of ligands to their receptors can activate phospholipase C, leading to the upregulation of cytosolic concentrations of the activators of PKC signaling, diacylglycerol (DAG) and Ca++ [112, 113]. The activation of PKC can upregulate several molecular pathways, including Akt, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and apoptotic pathways, to regulate tumorigenesis and metastasis [112]. PKC alpha, a PKC isoform, showed antitumor activity by inducing the polarization of TAMs within the TME [114]. Additionally, the protein levels of PKC alpha, beta and epsilon were found to be downregulated in cancers such as colon cancer [115, 116]. PKC theta, another isoform of PKC, showed tumor-suppressive effects by inducing immune suppression within the TME by controlling CTLA4-mediated regulatory T-cell function [117-119]. Conversely, phorbol esters, the naturally occurring activating ligands of PKC, showed tumor-promoting functions, suggesting that PKC could be an oncogene [111, 120, 121]. Moreover, within the TME, PKC beta, another PKC isoform, is a well-documented effector of the VEGF signaling that promotes angiogenesis and is required for invasiveness in certain tumors, such as pancreatic tumors [122-124]. Therefore, it is likely that different isoforms of PKCs or the same isoform within different contexts may act as tumor promotors or tumor suppressors in a context-dependent manner.

Nonetheless, combining existing therapies with novel molecules to modulate the dysregulated PKC signaling in cancer could be promising. Bryostatins, which are PKC activators, were shown to protect against phorbol ester-induced tumors [125]. Epoxytiglianes, another class of PKC activators, showed efficacy in preclinical mouse models and clinical mast cell tumors in canine models [126-128]. Another activator of PKC, tigilanol tiglate, has been approved for use in canine mast cell tumors [129]. Besides activators, CGP 41251, an inhibitor of PKC, has also shown anti-tumor activity and was found to reverse multidrug resistance when combined with adriamycin [130].

Although preclinical activation has led to the identification of complex PKC functions, their translation in clinical trials is impeded by a lack of mechanistic insights and robust pathological markers. This understanding is required to clinically address the action or inaction of the isoforms and to reveal the gain or loss of function of isoforms required for optimum efficiency of therapeutic interventions.

3.2 Notch signaling

Recent evidence indicates that a distinct population within tumors can express distinct Notch ligands or paralogues, which can both activate and inhibit tumor development in different cancers since the outcome of Notch signaling is highly changeable depending on the context. For instance, the presence of Notch ligand delta-like canonical Notch ligand 1 (DLL1) on DCs interacts with the NOTCH2 receptor on tumor cells to promote DC immunosuppressive function. However, jagged canonical Notch ligand 2 (JAG2) on DCs plays negative tumor-promoting roles Moreover, Notch mutations have been suggested to serve as predictive biomarkers for immune checkpoint therapy in various cancers. Thus, although not yet clinically successful, an integrative analysis with newer perspectives holds the potential for clinical developments [131].

Notch signaling plays a key role in determining cell fate and regulating embryonic as well as tumor angiogenesis [132, 133]. Notch receptors are heterodimeric, single-pass transmembrane receptors that interact with either one of their membrane-bound ligands (Jagged1, Jagged2, and Delta-like ligands Dll1, Dll3 and Dll4) to stimulate the expression of target genes [133]. In solid tumors’ TME, the activation of Notch signaling generally promotes oncogenesis [134]. For example, Notch ligand Dll4 is upregulated in tumor samples from clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients [135], and inhibiting Dll4 leads to the disruption of tumor vasculature within the TME [136, 137]. However, Notch signaling functions as a tumor suppressor in the malignancies of myeloid origin, such as acute myelogenous leukemia and chronic myeloid leukemia [138, 139]. Moreover, a chronic blockade of Notch signaling leads to vascular tumors of the liver, skin, ovary, testes and colon in mice [140, 141].

Demcizumab and enoticumab (Dll4 targeting antibodies) alone or in combination with existing antitumor drugs, and Rovalpituzumab (anti-Dll3 targeting antibody) work by suppressing cancer stem cells and angiogenesis in the TME and have progressed to randomized phase II trials [142-144]. Brontictuzumab (anti-Notch1 receptor antibody) and Tarextumab (anti-Notch2/3 receptor antibody) were tested in relapsed or refractory tumors, small-cell lung cancer and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, but clinical trials were discontinued owing to a low response rate in patients [145-147]. MEDI3622 (anti-TACE antibody) showed promising preclinical activity in human colorectal adenocarcinoma progression [148, 149]. Inhibiting γ-secretase using small molecules like PF-03084014 and BMS-906024 has shown promising results in triple-negative breast cancer, desmoid tumors and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and related phase II and III trials are currently underway [150-153]. Small molecule and peptide inhibitors of the intracellular domain of the Notch receptor (NICD)-transcriptional complex assembly have been developed, and phase I/IIa clinical trials are being conducted on one such inhibitor, CB-103 (NCT03422679). Other categories of Notch inhibitors, such as IMR-1 and PRI-724, have been found to be effective in inhibiting the Notch-transcriptional complex in in vitro model of triple-negative breast cancer [154].

Although extensively studied in the past several decades, Notch signaling therapeutics have failed clinical expectations. The major shortcomings are high cytotoxicity, shown by pan-NOTCH inhibitors, and low affinity of antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). To combat these issues, it was suggested to investigate novel isoform-specific drugs with high ADC affinity. Moreover, combination therapies targeting chemoresistance, endocrine resistance and radio-resistance also hold promise.

3.3 TGF-β signaling

TGF-β therapeutics have recently shown great promise with the use of TGF-β-neutralizing antibodies and ligand traps, which inhibit the binding of TGF-β with its receptors [155]. Moreover, dosing strategies to bypass cellular toxicity or specifically target TGF-β isoforms that are maximally linked to cancer progression hold promise in clinics to avoid the cytotoxicity of TGF-β inhibitors [155].

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a family of cytokines that intricately regulate embryonic development, tissue homeostasis and regeneration [156]. Moreover, they regulate various aspects of cancer cells, such as adhesion, differentiation, cell cycle progression and apoptosis [157, 158]. TGF-β signaling plays a biphasic role in TME and cancer progression. It acts as a tumor suppressor in the initial stages of malignancies by suppressing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis [159]. However, cancer cells adapt to the protective TGF-β signaling and utilize its moonlighting functions to create a conducive TME by activating CAFs, promoting angiogenesis and ECM production, and suppressing anti-tumor immune responses [160-162].

Various strategies have been adopted to target the deregulated TGF-β signaling, including neutralizing antibodies to target either ligands or receptors, ligand traps, small-molecule inhibitors, and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). Fresolimumab, a human monoclonal antibody against TGF-β in a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT00356460), demonstrated preliminary evidence of anti-tumor activity in malignant melanoma and renal cell carcinoma [42]. LY3022859, an antibody against TGF-β receptor 2, showed survival benefits in mouse models [163]. TGF-β ligand traps are chimeric fusion proteins designed to prevent TGF-β from binding to its receptors. AVID200, a ligand trap for TGF-β1 and TGF-β3, showed anti-tumor activity in mouse models [164] and feasibility in clinics in patients with advanced solid-state tumors in a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03834662) [165]. Moreover, various small molecule inhibitors of TGF-β, including galunisertib (LY2157299) [166-168], vactosertib (TEW-7197) [169-171] and LY3200882 [172], have shown specific antitumor activity. Lastly, phase 1 clinical studies with trabedersen (AP12009), Lucanix (belagenpumatucel-L), or with ASOs against TGF-β2 mRNA, showed better survival in glioblastoma, melanoma, pancreatic cancer or colorectal cancer patients [173, 174].

The pleiotropic effects of TGF-β in tissue homeostasis have rendered exploiting their pro-tumorigenic properties difficult, as targeting TGF-β can systemically affect healthy tissues and tumor cells, thus safety concerns. Thus, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of TGF-β in their regulation of normal and cancerous cells is required. Moreover, stratifying patients based on biomarkers who may benefit from TGF-β targeting is essential.

3.4 ER stress response pathways

The presence of hypoxia [175, 176], reduced nutrient availability [177, 178], accumulation of reactive oxygen species [179, 180] and a decreased pH within the TME [180, 181] contribute to a chronic upregulation of ER stress in the TME, impacting the fate and survival of cancer cells. Additionally, oncogenic transformation contributes to the constitutive activation of ER stress sensors such as inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), leading to persistent activation of ER stress by cancer cells [182]. Such chronic activation of ER stress modulates the TME by reducing the surface expression of major histocompatibility complex class 1 and 2 proteins, thereby impeding immune recognition of the cancer cells by NK cells [183, 184]. Therefore, reducing the ER stress load could be utilized to target TME for more favorable treatment outcomes.

Therapies modulating ER stress response pathways by inhibiting IRE1α, PRKR-like ER kinase (PERK) and molecular chaperone binding-immunoglobulin protein (BiP) have shown success in various preclinical and clinical studies. IRE1α inhibitors KIRA8 or AMG-18, STF083010, MKC8866 and MKC3946 reduced tumor growth in various cancers, including multiple myeloma [185-187], melanoma [188], breast cancer and prostate cancer [189]. Similarly, PERK inhibitors GSK2606414 and GSK2656157 possess antitumor activity and can reactivate T cell function in the TME in mouse embryonic fibroblasts; however, these compounds had adverse effects in mouse models, hindering their progress toward clinical trials [190-193]. Further, suppression of BiP signaling by KP1339 (also known as IT-139) or HA15 in glioblastoma, bladder or breast cancer cell lines has been shown to enhance the response to anti-cancer therapy [194, 195].

3.5 Modulation of the TME by lactate bioavailability

Targeting lactate transporters, such as solute carrier family 16 member 1 (SLC16A1) and member 7 (SLC16A7), to reduce lactate levels in tumors has shown huge preclinical success. Another approach to inhibit the conversion of pyruvate to lactate through targeting lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) is useful in inhibiting the oncometabolic lactase functions and revoking T cell- and NK cell-mediated immunosuppression in various cancers [108].

Due to elevated glucose uptake rates, cancer tissues have high levels of metabolic by-products like lactate that can be partly attributed to the accelerated metabolism of cancer stem cells and other constituents of the TME [2, 196]. Recent reports suggest the role of proton-coupled lactate efflux in maintaining an acidic phenotype in the TME, thereby promoting angiogenesis [197, 198], cell invasion [198] and metastasis [199-202]. Additionally, high lactate concentration in the TME inhibits the maturation of monocytes to dendritic cells [203, 204] and reduces cytokine production and cytotoxic activity by T cells and NK cells [205-207], thereby contributing to suppressed immune recognition of cancer cells.

Suppression of lactate efflux by cancer cells using the small molecule inhibitor AZ3965, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate (CHC), has shown promising results in preclinical models of Burkitt lymphoma, breast cancer, gastric cancer, small cell lung cancer and glioblastoma [208, 209]. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase-A, a key gene involved in lactate synthesis using N-hydroxyindoles and galloflavin or genetic ablation of LDHA, reduced tumorigenesis in non-small cell lung cancer[210], pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [211, 212] and cervical cancer cells [212, 213].

Despite understanding the pathogenic roles of lactate, how its targeting affects host anti-tumor immunity and synergizes with other anti-cancer immune therapies still needs to be explored since lactate also partly modulates the metabolism in the TME as an energy source, signaling molecule, and as a key tumor immunosuppressive factor [202]. Moreover, identifying more potent lactate transporter and LDHA inhibitors warrants improving anti-cancer therapies.

3.6 Metabolic reprogramming of the TME

Metabolic reprogramming is an essential hallmark of cancer characterized by the ability of cancer cells to reprogram the metabolism of non-cancerous cells, specifically immune cells, to go against their nature, help in tumor progression, and better adapt to the limited availability of nutrients in the TME [214-216]. This reprogramming, via regulating metabolic enzymes’ activities, helps enrich the TME with nutrients and plays a causal role in tumor progression [217, 218].

The metabolic niche of the TME is regulated by four key factors: 1) intrinsic metabolism of the tumor cells, 2) tumor-non-tumor cell interaction, 3) location and heterogeneity of the tumor, and 4) metabolic homeostasis of the body [219]. Regarding intrinsic metabolism, several studies have demonstrated that tumor cells drive aerobic glycolysis and promote cell proliferation via fueling mitochondrial metabolism [220, 221]. Moreover, apart from glucose and lactate, tumor cells use fatty acids, proteins and amino acids as fuel [222, 223]. For example, glutamate is converted into aspartate in cells with a dysfunctional electron transport chain to promote proliferation, allowing tumor cells to adapt rapidly to the substrates available in their TME niche [224, 225].

T cells provide a natural defense against cancer cells as they can specifically kill tumor cells by recognizing tumor-specific antigens. However, glycolytic tumors have very low T cell infiltration and proliferation as activated T cells and tumor cells compete for glucose in the TME [226]. Limiting glucose levels leads to cellular competition; this impairs T-cell function via decreased mTOR signaling. Reduction in mTOR activity diminishes IFNγ transcripts in T cells, mitigating Th1 CD4+ T cell differentiation [227-229]. Furthermore, tumor cells compete with T cells for amino acids [230]. For example, glutamine is required for T-cell function and differentiation, and tumor cells use glutamine to activate STAT3 to promote cell proliferation [231].

The polarization of TAMs towards either the M1 (antitumoral) or M2 (protumoral) phenotype is dictated by cellular metabolism and thus regulates its response to tumor cells. Increased glycolysis by tumor cells leads to the formation of TAMs with low glycolytic potential, which promotes metastasis [232]. Moreover, tumor cells produce lactate which induces the M2 phenotype of TAMs via stabilizing HIF-1α and activating G-protein-coupled receptor 132 [210, 233, 234]. Glutamine metabolism in TAMs also promotes an M2 phenotype via the production of α-ketoglutarate, which aids in fatty acid oxidation and epigenetic activation of M2 genes [235].

Tumor location plays a key role in TME modulation because different organs and tissues have different proteomic and metabolic signatures. These differences determine the metabolite dependencies of tumor cells. Moreover, the perfusion level, tissue function and cell-type composition within the same organ also contribute to metabolic heterogeneity. For example, blood vessel proximity distinctly defines metabolic niches. Additionally, a significant correlation has been found between glycolysis, mitochondrial metabolism and local oxygen concentrations in a study conducted on human melanoma and head and neck cancers [236]. Glucose tracing studies stipulate that tumor cells in highly perfused locations rely mainly on glucose, whereas those in less perfused regions depend on other carbon sources [237]. Furthermore, solid tumors, being metabolically heterogeneous, show glutamine-depleted cores, which promote histone hypermethylation, resulting in the reduced expression of differentiation-related genes and cancer cell dedifferentiation [238, 239].

Although cellular metabolism and its role in the TME are well explored, the role of systemic nutrient levels in characterizing the metabolic environment of the TME is still elusive. Recent studies indicate that dietary restrictions and hormonal modulation affect local metabolism [240]. For example, dietary restriction of serine-glycine is beneficial in tumors lacking p53 because of their inability to counteract reactive oxygen species (ROS)-associated oxidative stress [241, 242]. Moreover, the gut microbiome also produces specific microbial metabolites that can be altered by dietary restrictions, thus affecting tumor cell metabolism [243].

Metabolic enzymes were previously considered to catalyze their specific reactions, and their roles were strictly limited to regulating metabolic pathways. However, research in the past decades indicated that these enzymes have a moonlighting function in phosphorylating various proteins that regulate many pathways ranging from cell-cycle progression and proliferation to apoptosis, autophagy and T-cell activation. Some of these enzymes are pyruvate kinase M2, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1, acylglycerol kinase, hexokinase and phosphoglycerate kinase 1 [244-247]. Moreover, the metabolic products of these enzymes play a crucial role in regulating gene expression [245, 248]. Interestingly, these enzymes perform their non-canonical functions via protein-protein interactions and regulate many central signaling pathways and functions of several organelles, such as the nucleus, ER and mitochondria [249]. Thus, unraveling the moonlighting functions of metabolic enzymes that help in tumor progression helps us to better understand the TME dynamics and can be exploited to develop better therapeutic interventions [250].

Several challenges hinder the targeting of the pro-tumorigenic metabolic profile of the TME. Targeting the tumor cells’ proliferative profile also affects normal cell metabolism at the systemic level. Combining these drugs with other cancer hallmarks, such as immunity, could increase the therapeutic window for targeting oncometabolites. Another prevalent strategy is to inhibit enzymes mutated in cancer, such as the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH) 1/2 mutation-induced oncometabolite D-2-Hydroxyglutarate (D2HG) in glioblastoma (GBM) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). IDH inhibitors have shown clinical success in AML and are under investigation with combination therapies in GBM. Thus, targeting tumor-specific metabolites in the optimum therapeutic window and exploiting cancer-specific vulnerabilities hold great potential in metabolomics [251].

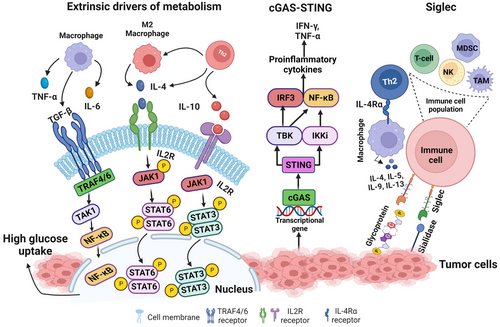

3.7 cGAS-STING signaling in the TME

Research on the cGAS-STING signaling promoting tumor progression is emerging in the field of cancer. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database categorizes 18 different malignant tumor types. Researchers have observed differences in the expression of essential genes in the cGAS-STING signaling mechanism between normal and malignant tissues, along with MB21D1-encoding cGAS, transmembrane protein 173 (TMEM-173)-encoding STING, TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK-1) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3). Comprehensive research and recent evidence proved that these four genes were significantly elevated in almost all cancer models, suggesting that cGAS-STING signal transduction might be stimulated in all cancer types [252, 253]. In some cancer models, extremely invasive tumors can ambiguously depend on and utilize the cGAS-STING pathway to modulate tumorigenesis with significant implications for cancer therapy [254]. NF-κB regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and survival of normal cells, thus acting as a crucial stimulator of the inflammatory response. Additionally, NF-κB promotes the development of inflammation, tumors and immune dysfunction [255]. Chromosomal instability induces chronic inflammatory signals by constantly activating the cGAS-STING signaling mechanism, which downstream NF-κB function and consecutively increases metastatic cancer cell progression [256] (Figure 1).

Moreover, TCGA dataset analysis revealed that the STING expression level in cancer is negatively correlated with infiltrating immune cells in various tumor models, demonstrating that significant upregulation of the cGAS-STING signaling mechanism predicts a poor prognosis in cancer patients [252]. It has been shown that various tumor cells can specifically advance the accumulation of astrocyte-gap junctions to enhance brain metastasis by expressing protocadherin 7 (PCDH7), composed of connexin 43 (Cx43)[257]. These junction carriers pass to the cGAMP, from cancer cells to adjacent astrocytes, to stimulate STING by triggering IRF-3 and TBK-1 to generate TNF and IFN-α. Similarly, as paracrine signals, these factors further activate the NF-κB and STAT-1 pathway in metastatic brain cells, thus promoting brain metastasis and resistance in lung and breast cancer therapy [257].

3.8 Siglec signaling in the TME

Tumor cells express an abnormal quantity of sialic acids on their cell surface [258]. Most sialic acids belong to negatively charged disaccharides masking the chains of glycan on glycoproteins and glycolipids [258, 259] and are known as sialoglycans. On tumor cells, sialoglycans are involved in tumor cell-to-cell interactions within the TME, and it was also suggested that sialoglycans with negatively charged moieties could form an invisible cover by protecting tumor cells from immune recognition [260]. A vaccination trial with autologous sialidase treatment in human breast and melanoma cancer revealed that the elimination of sialic acid elicited a robust antitumor and an immune response [261]. Studies over the past decades have suggested a clear function of sialoglycans in tumors via immune evasion, not only by shielding of antigens but also by sialic acids show robust immunomodulatory properties as sugar moieties [260, 262, 263]. Sialoglycans form different ligands for sialic acid binding proteins, i.e., Factor H (FH), to evade complemented activation and are proposed as a mediator of the selectin-independent adhesion of lymphocyte trafficking, plays an essential role in metastasis [258, 264, 265]. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) have specific interactions with the immunomodulatory properties of sialoglycans. In mammals, siglecs are divided into two groups: the structurally preserved siglecs- (1, 2, 4 to 15) and the CD33-related siglecs (3, 5 to 11, 14 to 16) [266, 267]. Tumor cells with abnormal expression of sialic acid upregulate siglec family expression to infiltrate immune cells in the TME. The function of inhibitory siglecs closely resembles the PD-1 immune checkpoint function (Figure 1) [266, 267]. TME also promotes abnormal sialylation in tumor cells and modulates the expression of siglec on infiltrating immune cells [268]. Future studies could explore the approach to target the dysregulation of the sialoglycan-siglec axis in cancer, which could contribute to shaping the immunosuppressive TME, composing an obstacle to overcome towards effective immunotherapy in cancers.

4 IMMUNOTHERAPY AND IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE SIGNALING IN TME

4.1 Checkpoint signaling mechanisms

Several inhibitory immune receptors have been identified and studied intensively in the TME immune population, such as PD-1, CTLA4, TIM-3, LAG3 and B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), and are termed “immune checkpoints”, which essentially indicate a molecule that acts as a guard of immune responses against tumors or pathogens. The immuno-suppressive functions of the immune checkpoints usually rely upon ligand-receptor interaction. Recent studies using advanced technologies, like mass cytometry (CyTOF) and single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq), followed by functional studies, have shown a dynamic and diverse immune landscape that facilitates the understanding of tumor heterogeneity in various cancers, including various tumor stages and genetic backgrounds. In the TME, exhausted T cells exhibit reduced effector function and increased expression of immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-1, CTLA4, TIM-3, LAG3, BTLA) [269]. In this section, we summarize several well-researched immune checkpoint receptor signaling mechanisms.

4.1.1 Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) signaling

Some tumors express PD-L1, which contributes to immune evasion by inhibiting cytotoxic responses. Thus, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies can promote T cell activation and enhance anti-tumor immunity by blocking the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1/PD-L2 [270, 271]. Typically, PD-L1 or PD-L2 are expressed on the surface of cancer cells or antigen-presenting cells and transduce a signal for cooperation with PD-1 expression on the cell surface of T lymphocytes to stimulate restraint signaling [272, 273]. Tumor cells secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs) having membrane-bound PD-L1, mostly to upregulate the PD-1 mechanism, thus decreasing T lymphocytes [274, 275]. Additionally, PD-L1 can interact in cis with Cluster of differentiation 80 (CD80) to PD-1 [276-278], which may disturb the PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction and the CTLA4 and CD80 interaction and also maintain the flexibility of CD80 to trigger the signaling of CD28 [277, 279]. Consequently, the cis PD-L1 and CD80 interaction influences antitumoral immunity by abolishing PD-1 and CTLA4 functions. In contrast, ligand involvement with PD-1 causes a mutation in immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) in cytotoxic T cells, which significantly abolishes tumor growth in the Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) model [280, 281]. Phosphorylated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (p-ITSM) primarily recruits Src-homology-region-2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP2) to dephosphorylate key signaling molecules to downmodulate PD-1 activity levels [282, 283]. Even though SHP2 is important for inhibitory signaling of PD-1 in most cases, T lymphocyte SHP2 deficiency can still be detrimental by reacting to the treatment of anti-PD-1 antibodies in vitro, thus revealing an alternate signaling pathway [284, 285]. Reports also showed that phosphorylated PD-1 ITSM could recruit SHP-1 to play a role in the T-cell inhibitory mechanism [286]. Previous studies showed quantitatively applied mass spectrometry of PD-1 signalosome assembly in primary effector T cells and confirmed that PD-1 mainly recruited SHP2 [282, 287, 288]. Deep immune profiling of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-refractory and responsive in mouse models using Cytometry by the time of flight (CyTOF) showed that ICI-refractory in glioma tumors was associated with accumulating PD-L1+ TAMs and lack of MHC-II+ antigen-presenting cells [289]. It is important to note that multiple TAM subpopulations likely drive the immune evasion of GBM. In addition to PD-L1+ TAMs, CyTOF and scRNA-seq analyses revealed that CD73high macrophages are immunosuppressive cells and have a signature distinct from microglia that persist after anti-PD-1 treatment [269, 290, 291]. A transcriptional study of the PD-1-modulated activation on individual populations of T cells confirmed that PD-1 signaling largely inhibits transcriptional genes generated by the powerful T cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathway [292, 293]. Emerging evidence leveraged translationally to improve anti-PD-L1 therapy, and future studies can minimize it by avoiding the resistance and using combination therapy, for example, through companion biomarkers and/or identifying novel targets that could be modulated to overcome resistance.

4.1.2 Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) signaling

New studies suggest that CTLA4 blockade within the TME could decrease the activation threshold of T cells while selectively depleting immunosuppressive regulatory T cells, which can increase the number of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [294]. CTLA4 binds to CD80 or CD86 with higher binding affinity and impedes CD28 co-stimulation [295, 296]. T cells expressing CTLA4 on the surface can decrease CD80 and CD86 expressions on APCs by undergoing trans-endocytosis and inhibiting CD28 signaling [297]. It is commonly known that the CTLA4 cytoplasmic domain recruits SHP2 and contains YVKM motifs, which are considered to recruit SHP2 [298]. Some studies reported that there might be phosphotyrosine-independent cooperation among SHP2 and CTLA4 as alternated tyrosine CTLA4 could interact with SHP2 and inhibit TCRζ signaling pathways [299, 300]. Evidence also confirms no immediate interaction between CTLA4 and SHP2. However, it is perhaps arbitrated through the PI3K protein [301]. Further studies have suggested a disturbing action of CTLA4 on ZAP70. Micro-clusters are established when the ligands bind to TCR, and ZAP-70 reacts and arbitrates on the downstream pathway. CTLA4 disrupted the ZAP70 cluster formation in most T cells, although 5%-10% of T cells demonstrated cluster forming followed by anti-CD3 treatment [302-304]. A study reported almost no effect on ZAP70. Instead, the activation of T cells was associated with impaired c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) signaling activation [305, 306]. Consequently, the inhibition of CTLA4 could be achieved without the degradation of CTLA4 and adverse events caused by toxicity. Exploring CTLA4's inhibition in combination with other checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1, could improve the therapeutic efficacy compared to their single inhibition.

4.1.3 T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3) signaling

The interest in studying the ICI TIM-3 comes amid growing efforts to boost the efficacy of ICI immunotherapy. TIM-3 expression has a “complex biology” that negatively affects the immune system. Nevertheless, tyrosine kinase FYN and human leukocyte antigen B (HLA-B)-associated transcript 3 (BAT3) were suggested to inhibit the cytoplasmic tail of TIM-3 signaling [307-309]. It is hypothesized that when TIM-3 is unbound, BAT3 is confined to bind TIM-3 cytoplasmic motif and engage the intermediary form of lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK). In this condition, T cell activity was not inhibited. The binding state of TIM-3 with ligands activates the phosphorylation of Tyr256 and Tyr263 tyrosine residues by IL-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK), followed by ligand binding, releasing BAT3 into the cytoplasm [310, 311]. Release of BAT3 suggests that FYN tyrosine-protein kinase links with the TIM-3 cytoplasmic tail to generate inhibitory signaling that causes anergy of T cells by activating the transmembrane protein phosphoprotein membrane anchor with glycosphingolipid microdomains 1 (PAG1). This prompts the recruitment of tyrosine kinase (CSK), leading to phosphorylating LCK and suppressing T cells [308, 312]. Another inhibitory signaling mechanism discussed is the colocalization of TIM-3 with CD45 and CD148 at the immunological synapse, where T cell function was suppressed [313]. The latest study showed that the binding for a short term of the extracellular motif of TIM-3 amidst phosphatidylserine (PS) leads to the activation of TCR signaling. Another data revealed that the blockade activity of the TIM-3 or galectin 9 axis is due to the action of galectin 3 by clustering TIM-3 to inhibit the binding to PS [314]. Nevertheless, the binding of TIM-3 to PS in NK cells abrogated the activity and all-inclusive cytokines production [315]. It is known that TIM-3 action is based on different ligand interactions, and investigative efforts are focusing on pairing novel agents directed at TIM-3 activity with PD-1/PD-L1 immune ICI therapy [316, 317].

4.1.4 Lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3) signaling

LAG3 interacts with its ligands to regulate the function of T cells. The ligands of LAG3 are not only limited to MHC II as well as other ligands like galectin 3 (Gal-3), α-synuclein fibrils (α-syn), lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cell C-type lectin (L-SECtin) and fibrinogen-like protein 1 (FGL-1) [318-320]. In TCR signaling engagement, the LAG3 cytoplasmic tail arbitrates the inhibitory signaling through 3 conserved motifs, glutamate proline di-peptide multiple repeats (EP), a KIEELE, and a serine phosphorylation (S484) motif. It is known that the inhibiting action of LAG3 is not directly contemplated by eradicating the interaction between MHC-II and CD4 [321]. Some confirmed data showed that inhibitory signaling is triggered when LAG3 and CD-3 interlink. When LAG3 physically interplays with the complex of CD3 or TCR, it decreases the stimulative alteration of the complex. In addition, besides this, it also abolishes the activity of calcium influx. The essential role of LAG3 is to reduce the T-cell counter, but it does not necessarily induce any apoptosis in T cells [322, 323]. It is already illustrated that the specific KIEELE motif is a vital sequence necessary for blocking the signaling pathway. Notably, a single lysine residue (Lys468) exerts an inhibitory effect in CD4+ T lymphocytes at 468 motifs within the KIEELE [324]. However, LAG3 can positively induce Treg cell activation and stimulate its immunosuppressive function [325, 326]. LAG3 may synergize with other inhibitory molecules (PD-1, CTLA4) to improve the inhibitory activity of Treg cells, leading to APC-induced immune tolerance [327]. LAG3 can activate the maturation and stimulation of DCs through the regulation of intracellular phosphorylation protein and promote chemokines like tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [328]. LAG3, highly expressed on the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), interacts with ligands located on the surface of tumor cells to cause T cell dysfunction or even exhaustion, promoting tumor immune escape, particularly evident in CD8+ T cells [329, 330].

4.1.5 B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) signaling

BTLA is the essential co-signaling immune checkpoint protein with bidirectional functions [331]. BTLA contains ITIM and ITSM motifs and stimulates the inhibition of Grb2 protein in its cytoplasmic domain. Due to adaptor signaling, Grb2 recruits the p85 protein subunit of the PI3K or Akt signaling mechanism, inducing the proliferation of B and T lymphocytes [332]. ITIM and ITSM, both tyrosine residues, are phosphorylated in BTLA signaling to recruit SHP1 and SHP2, which inhibit lymphocyte functional signaling. BTLA compels the strongest phosphatase SHP1 to abrogate the CD28 and TCR signaling mechanisms. In contrast, PD-1 signaling recruits the weakened phosphatase SHP2 [282]. In addition, BTLA and herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) shares ligand on the same T lymphocytes (CD8+), and the same cell interaction happens, which suppresses T cell function [333]. On the other hand, on APCs, when HVEM is attached to BTLA on T lymphocytes, it invigorates downstream NF-κB signaling, which leads to APC maturation [334]. The unique interaction between HVEM and BTLA allows for bidirectional signaling, which elucidates an understanding of the opposite or dual roles of HVEM and BTLA and the approach for their specific targeting in treatment.

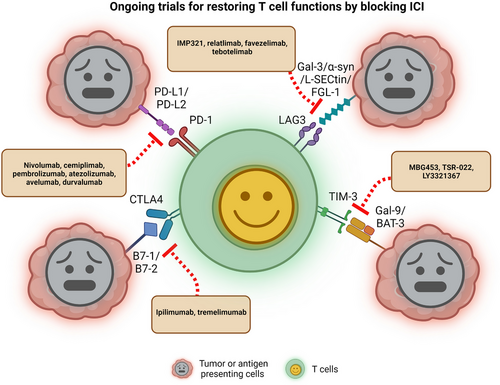

4.2 Immunotherapies targeting immune checkpoint signaling

In recent years, the TME has appeared as a promising approach for targeting several cancers. Here we discuss recent research targeting immune checkpoint signaling by blockade antibodies, ICIs, or various tumor-suppressive blocking peptides, nanoparticles, and CAR-T cell therapy to target the receptor-ligand intercommunication and attenuate T cell function to kill tumor cell progression. Many studies or clinical trials have conquered and are authorized for clinical translation [335]. Nonetheless, the overall survival response for these immunotherapies is not enough and needs a more comprehensive study [335]. Blocking antibodies PD-1 or PD-L1 is the most widely used in various cancer models as immunotherapy. T cell-targeted immune modulators are used as monotherapy or combination treatment with chemotherapies for almost all cancer types [336, 337]. Active clinical trials on different immune checkpoint proteins in several cancer models are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. Recently small molecules have been studied and shown to have the potential to emerge into immune checkpoint inhibitors with nanomolar binding affinity to PD-L1. Conceivable data revealed abolished PD-1 and PD-L1 interactions, improved T-cell activity, and enhanced antitumor immunity in colon, breast, pancreatic, and kidney cancer models [338-341]. Recently, glioblastoma mouse models revealed the inhibition of intratumoral immune-suppressive microglia or macrophages into the TME and increased CD8+ T cell infiltration, activation, and cytotoxicity into the tumor tissue and synergizing with anti-PD-1 combination therapy [342, 343]. In contrast, to intensify the T cells’ function and minimize the adverse effects of using CTLA4 immunotherapies, ICI treatment using combinations of anti-PD-1 (nivolumab) and anti-CTLA (ipilimumab) have shown to boost CD8+ T cell activation, proliferation, enhance the Teff cell memory (CD8+) and produce interferon-γ and granzyme-B in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) patients [344]. Recently, the US FDA-approved PD-L1 inhibitors atezolizumab and durvalumab were combined with carboplatin plus etoposide (CP/ET) to target and kill aggressively growing tumors in advanced SCLC patients and reported an overall increase in survival [345, 346]. Recent data from several clinical trials are encouraging combination therapy with a TIM-3 directed antibody (TSR-022) and PD-1 together with chemotherapy for patients with NSCLC [347]. The researcher explained that the combination regimen was well tolerated across multiple dosing levels and that the responses showed the strategy is worth pursuing. Anti-LAG3 monoclonal antibody relatlimab was also evaluated in several advanced solid tumors such as head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), melanoma, NSCLC, renal cell carcinoma and bladder cancer, and the trial evaluated the efficacy of relatlimab, mono-immunotherapy or in a combination regimen with an anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab [348]. LAG3 may synergize with other inhibitory molecules (PD-1, CTLA4) to improve the inhibitory activity of Treg cells, leading to APC-induced immune tolerance [327]. Several ongoing clinical trials investigating the blockade of TIM-3 inhibitor (sabatolimab) with or without PD-1 inhibitors in advanced solid tumors concluded that the doses for combination therapy of sabatolimab and spartalizumab were under tolerance and showed anti-cancer activity with survival benefits [349]. Moreover, CAR-T cell therapy is emerging to be a progressive new pillar in immune cell therapy for cancer, which has yielded remarkable clinical responses in patients with B-cell leukemia. However, many challenges remain to be addressed to overcome its ineffectiveness in treating solid tumors and hematological malignancies [350]. The great potential of CAR-T cell therapy at the beginning or earlier during the treatment course was unraveled, and the strategy revealed higher success rates and reduced toxicity associated with anticancer treatments [351]. Early administration of the therapy may also provide access to a higher proportion of naïve unexposed T-cell population, which is beneficial to facilitate the production of CAR-T cells. Finally, immunotherapeutic development of targeting immune checkpoint signaling molecules has promptly increased over the decade. The development of new biomarkers or identification of new targeting mechanisms with combinational strategies and novel nano-drug delivery strategies could significantly boost immunotherapy benefits in an effort to improve the quality of life for cancer patients by enhancing overall survival and eventually eliminate cancer.

| Treatment | Drugs/regimen | Condition or disease | Target | Clinical Trial No. | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | Leflunomide | smoldering multiple myeloma | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase | NCT05014646 | Phase 2 |

| Pemetrexed | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase | NCT00102804 | Phase 3 | |

| Metformin Hydrochloride | HER2-positive breast cancer | MAP kinase, Akt, mTOR | NCT03238495 | Phase 2 | |

| AZD3965 | Burkitt Lymphoma, Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma, Adult Solid Tumor | Monocarboxylate transporter 1 | NCT01791595 | Phase 1 | |

| L-asparaginase | Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Metastatic | Asparagine synthetase | NCT02195180 | Phase 2 | |

| Methotrexate | primary CNS lymphoma | Dihydrofolate reductase | NCT04609046 | Phase 1 | |

| 5-Fluorouracil | Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Thymidylate synthase | NCT02620800 | Phase 1 | |

| Hydroxyurea | Leukemia | Ribonucleotide reductase | NCT05005182 | Phase 2 | |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate amidotransferase | NCT01503632 | Phase 3 | |

| Enasidenib/AG-221 | Hematologic Neoplasms | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 | NCT01915498 | Phase 1/2 | |

| CB-839 | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Glutaminase | NCT04250545 | Phase 1 | |

| Immunotherapy | Pembrolizumab | Colorectal cancer | PD-1 | NCT02563002 | Phase 3 |

| Nivolumab | Melanoma | PD-1/PD-L1 | NCT01721772 | Phase 3 | |

| Cemiplimab | NSCLC | PD-1/PD-L1 | NCT03088540 | Phase 3 | |

| Nivolumab, Ipilimumab combined with chemotherapy | NSCLC | PD-L1 | NCT03215706 | Phase 3 | |

| TSR-022+Nivolumab combined with chemotherapy | Advanced solid tumors | TIM-3/PD-1 | NCT02817633 | Phase 1 | |

| Atezolizumab + Carboplatin + Etoposide | SCLC | PD-L1 | NCT02763579 | Phase 3 | |

| Varlilumab and nivolumab | Recurrent glioblastoma | Anti-CD27 and anti-PD-1 | NCT02335918 | Phase 1/2 | |

| Atezolizumab combination Nab-Paclitaxel | Breast cancer | PD-L1 | NCT02425891 | Phase 3 | |

| Pembrolizumab and vorinostat combined with temozolomide | New diagnosis GBM | PD-L1 | NCT03426891 | Phase 1 | |

| Pembrolizumab and Bevacizumab | Recurrent glioblastoma | PD-1 and VEGF | NCT02337491 | Phase 2 | |

| Tremelimumab and durvalumab in combination or alone | Malignant Glioma, Recurrent Glioblastoma | CTLA4 and PDL1 | NCT02794883 | Phase 2 | |

| Nivolumab and ipilimumab | Mesothelioma | PD-L1 | NCT02899299 | Phase 3 | |

| Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | PD-L1 | NCT03434379 | Phase 3 | |

| ICT-121 DC vaccine | Recurrent gliomas | Dendritic cell Vaccine | NCT02049489 | Phase 1 | |

| MBG453 | Hematologic malignancy | TIM-3 | NCT03066648 | Phase 1 | |

| LY3321367 | Advanced solid tumors | TIM-3 | NCT03099109 | Phase 1 | |

| TTF(Optune), Nivolumab Plus/Minus Ipilimumab | Recurrent glioblastoma | PD-1/PD-L1 | NCT03430791 | Phase 2 | |

| Atezolizumab combination with Cobimetinib + Vemurafenib | Melanoma | PD-L1/BRAF kinase | NCT02908672 | Phase 3 | |

| Nivolumab | Recurrent or progressive IDH-mutant gliomas | PD-1/PD-L1 | NCT03557359 | Phase 2 | |

| IMP321 (anti-LAG-3) + Pembrolizumab | Melanoma | LAG-3/PD-1 | NCT02676869 | Phase 1 | |

| IMP321 (anti-LAG-3) + Paclitaxel | Breast cancer | LAG-3/PD-1 | NCT02614833 | Phase 2 | |

| BMS-986016 + Nivolumab | Melanoma | LAG-3/PD-1 | NCT05002569 | Phase 3 | |

| Favezelimab/Pembrolizumab | Colorectal cancer | LAG-3/PD-1 | NCT05064059 | Phase 3 |

4.3 Immunosuppressive chemokine cell signaling into the TME

The chemokine gradient determines the composition of the TME. Pro-tumor chemokine gradient attracts immune suppressive immune cells and excludes effector immune cells. On the other hand, the antitumor chemokine gradient favors the migration of effector immune cells. Here, we discuss key chemokine signaling axes in tumors and immune crosstalk therapeutically targeted to make the TME less immune suppressive.

4.3.1 CCR4-CCL22/17 signaling axis in the migration of regulatory T cells into the TME

Regulatory T cells suppress immune responses against tumors and their normal function to maintain immune tolerance in physiological conditions [352]. The CCR4-CCL17 signaling axis induces chemotaxis of CCR4+ T cells, mainly Th2 and Tregs, generating an immunosuppressive TME [353]. CCL17 acts as a ligand for CCR4 and is produced by DCs or endothelial cells [354, 355]. These observations were made in the context of gastric cancer and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Similarly, CCL22 is also another ligand of CCR4. In breast cancer, the CCR4-CCL22 signaling axis was reported to induce increased migration of regulatory T cells in TME, which in turn leads to the exclusion of effector T cells in the TME [356, 357].

4.3.2 CCR2-CCL2 axis and CCR5-CCL5 signaling axis in the migration of TAMs into the TME