A self-caricature of michelangelo buonarroti hidden in the portrait of vittoria colonna

Abstract

The specialized literature has described how the great anatomist par excellence, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), like many other renowned artists of his time, included a self-portrait in many of his works. This article presents novel evidence that Michelangelo inserted his self-portrait into a sketch of his close friend, Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547). This work, made by Michelangelo in 1525, is currently in the collection of the British Museum in London, England. This self-portrait of Michelangelo can serve as a tool for analyzing the artist's probable bodily dimensions and even his state of health during this period of his life. Clin. Anat. 31:335–338, 2018. © 2018 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

La mia pittura morta

difendi orma', Giovanni, e 'l mio onore,

non sendo in loco bon, né io pittore.

My dead painting

defend now, Giovanni, and my honor,

for I am not in a good place, nor am I a painter.

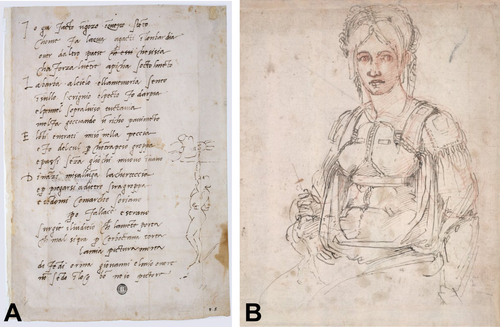

(A) Michelangelo Buonarroti's self-caricature made in 1509, painting the Sistine Chapel, next to a sonnet dedicated to his friend, Giovanni da Pistoia (283 × 200 mm, Casa Buonarroti, Florence, Italy). (B) Half-length figure of the portrait of Vittoria Colonna made by Michelangelo Buonarroti in 1525 (Pen and brown ink over red and black chalk, made up strip in the upper and lower right corner −32.3 × 25.8 cm, British Museum, London, England). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The specialist literature (Crispino, 2001; Cliulich and Ragionieri, 2004; Blech and Doliner, 2008; Parker, 2010; Vasari, 2011; Vaughan, 2016) has treated this famous caricature as the only known representation of the artist. Therefore, some authors (Gallenga et al., 2012; Lazzeri et al., 2016) have used it as a tool for analyzing the artist's probable bodily dimensions and even his state of health during the period in which he painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. However, this article provides surprising and novel evidence that Michelangelo included a similar self-caricature in another of his drawings, which is currently held in the collection of the British Museum in London, England.

ANALYSIS

Among the many Michelangelo drawings in the British Museum collection is one that is less well-known but nevertheless deserves special mention, especially because it is thought (Chapman, 2006; Musiol, 2013) to depict a celebrated close friend of Michelangelo, Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547) (Figure 1B).

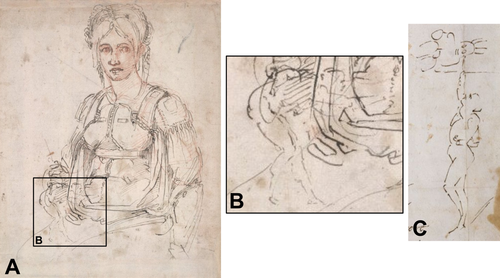

In this portrait of Vittoria Colonna by Michelangelo, made in 1525 (Figure 2A), a figure remarkably similar to that drawn by the artist in 1509 for his friend Giovanni da Pistoia stands in the area immediately in front of her abdomen and between the lines that form part of her dress (Figures 2B and 2C). The only significant difference between the caricatures is the posture; in the drawing depicting Vittoria Colonna the caricature leans forward at an acute angle, as if the caricature itself were drawing the portrait of Vittoria Colonna (Figure 2B).

(A) In the drawing of Vittoria Colonna (32.3 × 25.8 cm, British Museum, London, England), it is possible to see in detail/highlighted (B) a caricature inserted between the lines that form the dress. Note the striking similarity of this caricature (B) to Michelangelo Buonarroti's self-caricature (C) made in 1509, especially between the faces. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

At the time of Michelangelo Buonarroti there were many restrictions on artists and their work, perhaps the main one being that no artist was allowed to sign his works, especially those made for the Catholic Church hierarchy. The stated purpose of this rule was to keep the artists in their places and protect them from the sin of pride. However, the patron who paid for the work had his name, image and/or symbol of his family displayed prominently. This was the main reason why many artists of that era discreetly inserted their own faces within their works. In some cases, for example paintings by Botticelli and Rafael, this was obvious, since they had the consent of their patrons. In other cases it was not so apparent (Blech and Doliner, 2008).

- In the skin of Saint Bartholomew (which is usually shown carrying all his skin intact and the knife used to skin him) in The Last Judgment fresco (1536–1541), located on the wall behind the altar of the Sistine Chapel, Rome, Italy. It is agreed that although the figure of Saint Bartholomew is completely bald and has a long grey beard, the face of the skin is beardless and is covered with dark hair. Thus, the two faces do not coincide; that of the skin is none other than Michelangelo himself. So, instead of using his signature, Michelangelo secretly signed the fresco with his own face.

- Another well-known self-portrait is part of his most famous Pietà, painted towards the end his life, which is currently in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo in Florence (Pietà de Bandini, 1550–1555). In this sculpture, the hooded figure holding Jesus from behind is Nicodemus. According to Christian tradition, Nicodemus symbolizes the concealment of true faith in order to survive and serve God. When we look closely at Nicodemus's face, we see Michelangelo's self-portrait.

In recent years, renowned authors (Barreto and Oliveira, 2004; Blech and Doliner, 2008; Tatem, 2010, 2013) have shown that Michelangelo, like other artists of his time, occasionally included his self-portrait among the figures that composed his works. However, none of these authors refers to the caricature discussed in this article. Not even the references (Cliulich and Ragionieri, 2004) found in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, Italy, indicate a probable caricature of the artist in the drawing of Vittoria Colonna.

This fact, although curious to say the least, might be understood since the caricature is part of a drawing held in a museum in England (the British Museum), far away from Florence and Rome, where most of Michelangelo's famous works are located and therefore attract more of the critics and scholars interested in them. The descriptions in the catalogues from the British Museum (Chapman, 2006) referring to this portrait of Vittoria Colonna by Michelangelo make no mention of any possible self-caricature of the artist.

The fact that the caricature is inserted between the lines that form the dress of Vittoria Colonna undoubtedly contributes to making it almost imperceptible at a quick glance. Also, any observer who noticed the caricature within the folds of the dress of Vittoria Colonna would have to be familiar with the other caricature drawn by the artist in 1509 for Giovanni da Pistoia to realize how similar they are. If the two drawings were exhibited side by side, then sooner or later someone (not necessarily a specialist in Michelangelo's works) would find significant similarities between the image hidden in the portrait of Vittoria Colonna and the self-caricature of Michelangelo from 1509.

With regard to the image made by the artist for Giovanni da Pistoia in 1509, some authors who have specialized in the works of Michelangelo (Cliulich and Ragionieri, 2004) have suggested the sketch is not a realistic self-portrait or a descriptive caricature, but only an indication of the content of the verses in a concise diagram. Without the verses the sketch would not have its full artistic effect, but when the sonnet has been read it synthesizes the meaning.

The specialized literature (Symonds, 2002; Blech and Doliner, 2008; Musiol, 2013; Smithers, 2016) describes Vittoria Colonna as being a great friend of Michelangelo. Years earlier, while still living in Rome, Vittoria became friends with Michelangelo, and their bonds grew stronger and stronger until her untimely death in 1547. They exchanged long letters, wrote poems in honour of each other, and on many occasions exchanged poems, gifts and favours. Many historians who wished to deny Buonarroti's love for men chose to use his poems for Vittoria as proof of his heterosexuality. Their love, however, was the epitome of what we would now call platonic. They loved their minds. Michelangelo was excited to have found in Vittoria an intellectual peer and a spiritual companion.

Thus, it would seem reasonable to infer that Michelangelo, holding Vittoria Colonna in such high esteem, might have intentionally inserted his self-portrait into a portrait of such a valued friend, represented as though the caricature itself (Michelangelo) was drawing Vittoria Colonna.

CONCLUSION

Many authors have pointed out that most of Michelangelo's works include various hidden symbols often associated with pagan, Neoplatonic beliefs, mathematical properties, and anatomical representations (Ackerman, 1986; Meshberger, 1990; Eknoyan, 2000; Strauss and Marzo-Ortega, 2002; Bondeson and Bondeson, 2003; Barreto and Oliveira, 2004; Tranquilli et al., 2007; Blech and Doliner, 2008; Suk and Tamargo, 2010; Reis et al., 2012; De Campos et al., 2015a, 2015b; Malysz et al., 2015; Di Bella et al., 2015; De Campos et al., 2016). In addition, the artist left poems and personal letters that explained some of these works and, at the end of his life, he dictated some of his memories to his amanuensis, Condivi, to elucidate many of his artistic intentions (Blech and Doliner, 2008).

However, none of the specialized literature described in this article mentions any sonnet/poem associated with Michelangelo's portrait of Vittoria Colonna, or any other specific description of a probable self-caricature of the artist inserted in the drawing. Nevertheless, the lack of any description of this self-caricature does not constitute evidence for its absence, and the images themselves provide a significant argument for the striking similarity between the caricature found in the Vittoria Colonna drawing and that previously made in 1509 for his friend Giovanni da Pistoia.