Integrating Gender Equality Into Strategy Using Management Control Systems: Case Studies From Japanese Companies

Funding: This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (22K01795).

ABSTRACT

In Japanese companies, gender equality has been one of the most pressing sustainability issues of the day. Accordingly, there has been a strong need to discuss gender issues from the perspective of Management Control Systems (MCSs). The degree to which gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy varies, depending on the configuration of each MCS. Thus, relying on the case studies of seven Japanese companies, this study investigates the configuration of MCSs based on their use and examines the degree to which the realisation of gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy. The results revealed the configuration of MCSs typified by their use and technical, organisational and cognitive dimensions in integrating gender equality into strategy in Japanese companies. This study contributes to research on management accounting and MCSs in gender accounting by showing the configurations of MCSs in terms of how gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy.

1 Introduction

Gender equality is a global issue that has been widely discussed by academics, businesses, governments, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and society (Eweje and Nagano 2021). Sustainable Development Goal 5, which aims to achieve gender equality and empower women, has still not been achieved despite strong commitments by many countries (G20 2024). Women's empowerment can be enhanced by increasing their labour participation and wages (Anderson and Eswaran 2009; Rahman and Rao 2004). However, the feminisation of poverty has exposed many women around the world to gender inequality (Crear-Perry et al. 2021; Leal et al. 2023; Odera and Mulusa 2020; Stoet and Geary 2018). While national economic development tends to reduce gender inequality, it has been observed that cultural norms and policymakers may hinder the promotion of gender equality (Duflo 2012; Seema 2015).

Japan is one of the few developed countries where gender inequality has yet to be extensively resolved, although the percentage of women in the country's workforce reached 45% in 2023, exceeding the global average of 42% (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications 2024; World Economic Forum 2024). It is worth noting that the participation of women in the workforce has increased over the past two decades, and the tendency for women to quit their jobs when they get married is weakening (Cabinet Office 2022a). However, an analysis of the employment status of working women aged 24–34—women who are married and have children—reveals that two-thirds of them are part-time workers who work less than 35 h a week, and one-third of them are full-time workers who work 35 h or more a week (Cabinet Office 2022a). In addition, although the proportion of employed women among all women has remained at around 80% between the ages of 25 and 54, the proportion of women with an annual income of 1.5 million yen or less is 43% for those aged 25 to 34 and 55% for those aged 35 to 54 (Cabinet Office 2022a). Almost half of working women earn less than 1.5 million yen a year1.

Survey data also exist showing that nearly half of both men and women agree that men should work and support the family (Cabinet Office 2022b)—a clear indication of ingrained notions in Japanese society about gender-based division of labour, wherein men are expected to do paid work while women engage in mainly unpaid work at home or work for pay only in their spare time2 (Tanaka and Nagano 2021). According to the World Economic Forum's (WEF) 2024 Global Gender Gap Report, Japan's gender gap index is 0.663, placing it 118th out of 146 countries. The index for participation in economic activities and equal opportunities is only 56.8%, placing it 120th out of 146 countries (World Economic Forum 2024).

Japanese companies have recently responded to societal demands for gender equality as a key sustainability issue (Eweje and Nagano 2021). Since the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law in 1985, there have been sustained efforts to promote gender equality in the workplace. In 2003, the Cabinet Office set a target of ‘expecting that, by 2020, women will account for at least 30% of leadership positions in all fields of society’. The 2015 Act on the Promotion of Female Advancement obliges large companies to promote gender equality (Article 8(1)). In order to address issues such as organisational homogeneity and high female turnover, companies are ensuring gender equality, respecting their employees' work–life balance and supporting women's career development (Hosoda and Nagano 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; PwC Consulting LLC 2019; Watanabe 2021). The percentage of women who were employed before having their first child, and who continue to work after having a child, is increasing due to legal reforms and corporate initiatives. As of 2019, the percentage of women who continued to work after having a child was 69.5%, and the government target of ‘a 70% rate of continued employment by 2025’ is within sight (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2023).

However, within the context of Japanese companies, the pursuit of gender equality is impeded by cultural norms, such as the division of labour by gender (Tanaka and Nagano 2021) and workplace practices (Watanabe 2021). The percentage of women in senior management positions in the workplace remains low in Japan—at 8.2% (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2024), compared to the global average of 31.7% (World Economic Forum 2024, p.7). The percentage of women in middle management positions in Japanese companies is 13.9%, and even in entry-level management positions, it is 24.1% (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2024). Notwithstanding the fact that women constitute 45% of the working population, most managerial roles are still occupied by men. Consequently, there is an urgent need to promote female managers to senior positions (Cabinet Office 2021).

Research on gender equality in the workplace has examined various aspects, including the impact of female board members on company performance (Jeong and Harrison 2017; Post and Byron 2015; Terjesen, Sealy, and Singh 2009). Studies have identified persistent barriers and explored how organisational culture and practices obstruct women's advancement (Atena and Tiron-Tudor 2020; Carli and Eagly 2016). While studies have examined the barriers to gender equality in Japan (Kobayashi and Eweje 2021; Lottanti von Mandach and Blind 2021; Yamaguchi 2019), significant disparities remain (Iida 2024; Kobayashi and Eweje; Nagase 2024). Moreover, little is known about the mechanisms for promoting gender equality in the workplace.

Accounting studies have focused on gender inequality within the accounting profession (Cooper and Senkl 2016; Kokot-Blamey 2021; Sian, Agrizzi, Wright, and Alsalloom 2020). Additionally, the disclosure related to gender equality has also been discussed to reduce the legitimacy of gender inequality by increasing stakeholders' attention to the issue (Al-Nasrallah 2023; Austin, Bobek, and Harris 2021; García-Sánchez, Minutiello, and Tettamanzi 2022; Miles 2011). A continuous discussion of the relationship between gender diversity and organisational performance is also evident (Gaio, Lucas, Poker Junior, and Belli 2024; Hazaea, Al-Matari, Farhan, and Zhu 2023; Provasi and Harasheh 2020; Ramon-Llorens, Garcia-Meca, and Pucheta-Martínez 2021).

However, the issue of gender equality within the context of management accounting and Management Control Systems (MCSs) remains unaddressed despite the identification of MCSs as a potential mechanism for promoting female managers to senior positions (Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Wittbom 2015; Wittbom and Hålen 2021). Thus, there is a need to discuss gender issues in the context of management accounting and MCSs (Burritt, Schaltegger, and Christ 2023; Hardies and Khalifa 2018; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Wittbom 2015; Wittbom and Hålen 2021; Parker 2008). There have been increased calls for a discourse on management accounting and MCSs that facilitate the establishment and achievement of the objective of transforming companies to address gender inequality as a social issue (Schaltegger, Christ, Wenzig, and Burritt 2022).

MCSs are defined as ‘the formal, information-based routines and procedures managers use to maintain or alter patterns in organisational activities’ (Simons 1995, p. 37). Emphasised in the literature is the necessity for the identification of ‘patterns of approaches to management controls for specific sustainability-related strategies while adopting a broader view of controls’ (Ghosh, Herzig, and Mangena 2019, p. 17). MCSs can support the integration of sustainability-related aspects, including gender equality, into organisational strategy by facilitating the planning and control of gender equality initiatives (Beusch, Frisk, Rosén, and Dilla 2022; Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Wittbom 2015; Wittbom and Hålen 2021). Through this process, MCSs can also enhance communication among top management as well as between top management and managers responsible for gender equality (Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023). The utilisation status of MCSs may influence their configurations. Ideal MCS configurations support integrating sustainability into organisational strategy (Beusch et al. 2022; George, Siti-Nabiha, Jalaludin, and Abdalla 2016; Gond, Grubnic, Herzig, and Moon 2012). However, while previous research has focused on the use of MCSs by companies to promote gender equality (Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Wittbom 2015; Wittbom and Hålen 2021), there are limited studies on the configuration of MCSs towards gender equality based on the use of MCSs and the extent to which gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy.

The lack of theoretical focus on the configuration of MCSs prevents any meaningful progress in exploring the potential of MCSs to strategically achieve gender equality. This is because the extent to which gender equality is incorporated into organisational strategy will vary according to the configuration of each MCS (Beusch et al. 2022; Ditillo and Lisi 2016; George et al. 2016; Ghosh et al. 2019; Gond et al. 2012). This typology derives the ideal types of organisations based on the relationships between organisational attributes (Doty and Glick 1994; Miller 1996). The configuration of organisational elements can be used to identify the optimal types by examining the interdependencies between the elements and themes derived from the relationships between them (Miller 1996). By focusing our analysis on MCS configurations, this research can also explore the relationship between MCSs usage and factors that can contribute to altering the dimensions for integrating gender equality into organisational strategy, thereby addressing a gap identified in previous research (Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024).

The issue of comprehending the function of MCSs in incorporating gender equality into organisational strategy gives rise to the following research question: How does the use of MCSs facilitate the integration of gender equality and organisational strategy? To address this research question, this study aims to examine the configuration of MCSs and assess the extent to which the realisation of gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy, utilising case studies of seven Japanese companies. Despite some progress in female workforce participation, Japan continues to face significant gender inequality. Entrenched societal norms concerning gender roles underscore the critical need to address this issue in Japan. The lens of MCSs can offer effective solutions to overcome the complex cultural and structural barriers that impede true gender equality in Japanese workplaces.

Thus, this study contributes to research on management accounting and MCSs related to sustainability by examining the configurations of MCSs towards the integration of gender equality into organisational strategy. The study also examines the path to each MCS configuration based on use of MCSs, with each path providing a theoretical framework for integrating gender equality into organisational strategy (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012). The proposed theoretical framework may be deployed to refine MCSs to advance gender equality in future research, thereby enhancing the rigour and relevance of the existing body of knowledge. The practical contribution of this study concerns its important implications for companies that are beginning to promote gender equality, as well as for those that will be encouraging gender equality efforts in the future. The proposed framework is designed to facilitate the assessment of the current status of gender equality within organisations, thereby providing the necessary information for decision-making processes aimed at further promoting gender equality. This study is equally important for policymakers, as the proposed theoretical framework can indicate the extent to which gender equality is promoted in organisations. Using this framework, policies that employ each MCS configuration can help address gender inequality based on the needs of each organisation. The configuration of each MCS for promoting gender equality that is identified in this study can help change gender roles in the workplace and develop female managers. In the end, this will help in achieving governmental goals to keep women in the workforce and develop them for management roles.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews prior research on the links between gender equality in the workplace and accounting and the links between MCSs and gender equality. Section 3 presents the theoretical framework of this case study. The fourth section outlines the research methodology, while the fifth section presents the findings. Section 6 discusses the findings, while Section 7 presents the conclusions and contributions while highlighting future research issues.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Gender Equality in the Workplace

Research on gender equality in the workplace has been conducted from diverse perspectives. For example, the impact of board gender diversity on corporate value and financial performance has been a topic of continuous discussion (Jeong and Harrison 2017; Post and Byron 2015; Terjesen et al. 2009). Some scholars have critiqued the research for its narrow focus on the financial merits of promoting gender equality, arguing that this is not a comprehensive solution to the issue of gender inequality (Kulik 2022). Gender equality has also been discussed as part of corporate responsibility (Grosser and Moon 2005, 2008).

Furthermore, the social construction of women's roles is established during youth and persists over an extended period, manifesting in the gender-based division of labour within the workplace (Brinton 1993; Fortin 2005). Numerous obstacles are faced by women in the workplace (Carli and Eagly 2016), and organisational practices that have a significant impact on gender were identified in the 1990s and persist to the present day (Atena and Tiron-Tudor 2020). The idealisation of extended working hours has precipitated an augmentation of the gender-based division of labour, culminating in gender inequality (Gascoigne, Parry, and Buchanan 2015). Additionally, there has been extensive research on the mechanisms underlying the gender pay gap (Christofides, Polycarpou, and Vrachimis 2013; Gascoigne et al. 2015; Goldin 2014; Mulligan and Rubinstein 2008; Roethlisberger, Gassmann, Groot, and Martorano 2023; Zamberlan and Barbieri 2023).

The various mechanisms that impede gender equality in Japan have been subjected to analysis from a multitude of perspectives. Managers' bias against female employees' way of work affects the promotion of female employees (Kobayashi and Eweje 2021). In response to the legal prohibition of gender-based discrimination under the Equal Employment Opportunity Law, Japanese companies have established two types of job: sogo-shoku and ippan-shoku. The primary responsibilities of the career-track position (sogo-shoku) entail core tasks, frequent job transfers and extended working hours, while the ippan-shoku is responsible for supporting the work of the career-track position (Hamada 2018; Yamaguchi 2019).

A notable distinction between these roles is that the ippan-shoku does not involve job transfers and the path to promotion is more limited (Hamada 2018; Yamaguchi 2019). The preponderance of women in the ippan-shoku has a discernible impact on their career progression (Yamaguchi 2019). Long working hours also still prevent women from getting promoted (Chang and England 2011; Dalton 2017; Yamaguchi 2016). Moreover, a significant proportion of women who enter into marriage and motherhood are reluctant to pursue career advancement, citing the demanding nature of the work–life balance required (Yamaguchi 2019). This often results in their departure from the labour market following the transition to motherhood (Hamada 2018; Lottanti von Mandach and Blind 2021).

Despite some evidence of promotion of gender equality in Japan (Hosoda and Nagano 2023; Min and Kim 2024), significant gender inequality persists in the country. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted the recruitment employment of married women with children, thus hindering progress towards gender equality in the workforce (Fukai, Ikeda, Kawaguchi, and Yamaguchi 2023). Iida (2024) addresses the different challenges faced by women, including balancing demanding work schedules with childcare and eldercare responsibilities. To address these challenges, Kobayashi and Eweje (2021) and Iida (2024) suggest the need for more family-friendly policies from the government and organisations. Nagase (2024) specifically calls for a reform of the social security system, which remains rooted in the traditional breadwinner model. Furthermore, fostering gender equality requires collaborative efforts among various stakeholders, including companies, families, schools, the government and individuals (Kobayashi 2021; Zhang-Zhang 2024).

So far, however, little is known about the mechanisms for promoting gender equality in the workplace in terms of management accounting and MCSs (Burritt et al. 2023; Hardies and Khalifa 2018; Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Wittbom 2015; Wittbom and Häyrén 2021). It is suggested that MCSs could play a facilitating role in the establishment and achievement of the objective of transforming companies to address gender inequality as a social issue (Schaltegger et al. 2022).

2.2 Gender Equality and Accounting

The field of gender accounting, which is feminist research in accounting, has contributed to our understanding of the patriarchal nature of the accounting profession and the diverse reasons for gender inequalities there (Hopwood 1987). Various studies have emerged from a feminist perspective on the issues faced by women in the accounting profession (Ciancanelli, Gallhofer, Humphrey, and Kirkham 1990; Hammond and Oakes 1992; Kirkham and Loft 1993; Lehman 1992; Thane 1992) alongside those focusing on gender inequality in the accounting profession (Cooper and Senkl 2016; Kokot-Blamey 2021; Sian et al. 2020). Furthermore, it has been argued that the disclosure of information pertaining to gender equality has the potential to diminish the legitimacy of gender inequality by eliciting concern among stakeholders (Al-Nasrallah 2023; Austin et al. 2021; García-Sánchez et al. 2022; Miles 2011). Additionally, there is an ongoing debate about the relationship between gender diversity and organisational performance (Gaio et al. 2024; Hazaea et al. 2023; Provasi and Harasheh 2020; Ramon-Llorens et al. 2021).

Despite the paucity of research on gender issues in the Japanese accounting domain (Kamla and Komori 2018), Komori (2008) has demonstrated that female accounting professionals in Japan have made a significant impact on Japanese accounting practice. They have done so by employing approaches that are unique to women and mothers in their daily work. Their thorough professionalism has firmly established women in the audit profession, with some of these women having succeeded in setting up their own firms. However, the issue of gender inequality in accounting has also been identified in other academic fields, including university-based research (Baldarelli, Baldo, and Vignini 2016; Dhanani and Jones 2017; Haynes and Fearfull 2008). These studies have demonstrated that, despite the efforts of researchers in this field, gender inequality remains a significant challenge.

The aforementioned studies indicate that women in accounting-related professions continue to encounter gender bias and discrimination in the workplace. It is anticipated that future gender accounting research will address gender inequality in the accounting profession (Grosser and Moon 2019; Haynes 2008). However, it is notable that gender accounting research has not yet explored the development of comprehensive solutions to address gender inequalities within organisational contexts.

2.3 MCSs, Sustainability and Gender Equality

From the perspective of the strategic implementation of solutions to sustainability challenges, MCSs support strategy changes through interactions within the organisation as well as interactions between the organisation and its environment (Narayanan and Boyce 2019; Simons 1991); MCSs can also be used to improve the performance of the intended strategy (Arjaliès and Mundy 2013; Ghosh et al. 2019; Gond et al. 2012). In management accounting, there has been research on how companies use MCSs to implement sustainability strategies (Arjaliès and Mundy 2013; Crutzen and Herzig 2013; Laguir, Laguir, and Tchemeni 2019).

Previous research has also addressed the design of MCSs, focusing on how they are structured in organisations; research has equally identified the patterns or configurations of MCSs that contribute to the implementation of sustainability (Beusch et al. 2022; Crutzen, Zvezdov, and Schaltegger 2017; Ditillo and Lisi 2016; George et al. 2016). However, previous studies have not examined the extent to which gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy and implemented in sustainability, which has a wide range of objectives. The different sustainability issues faced in different countries highlight the need to clarify how individual sustainability goals are integrated into organisational strategy and practised (Laguir et al. 2019).

In this context, studies have started examining how organisations use MCSs to achieve gender equality (Galizzi and Siboni 2016; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Wittbom 2015; Wittbom and Häyrén 2021). For example, Nagano and Hosoda (2023), through a case study of a major Japanese bank, found that formal and cultural MCSs are used interchangeably to achieve gender equality. However, few studies have been conducted to clarify the configurations of MCSs in relation to gender equality; similarly, there is a paucity of research on how gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy with each configuration (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Ghosh et al. 2019; Gond et al. 2012). Therefore, through case studies of seven Japanese companies, this study clarifies the configurations of MCSs based on the degree of use of MCSs and examines the extent to which the realisation of gender equality is integrated into strategy by MCS configurations.

3 Theoretical Framework

This study adopts Simons' (1995) MCSs framework known as Levers of Control (LOC) because it can help to determine how MCSs are used to implement corporate sustainability (Adib, Zhang, Zaid, and Sahyouni 2021; Arjaliès and Mundy 2013; Gond et al. 2012; Narayanan and Boyce 2019; Wijethilake 2017; Wijethilake, Munir, and Appuhami 2018). Specifically, studies on sustainability management using MCSs have considered cases based on the four systems in the LOC (Adib et al. 2021; Arjaliès and Mundy 2013; Narayanan and Boyce 2019; Wijethilake 2017; Wijethilake et al. 2018) and cases based on diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems (George et al. 2016; Wijethilake and Upadhaya 2020).

The diagnostic control systems in Simons (1995) are formal information systems used by managers to monitor organisational performance and correct deviations from preset standards of performance (Simons 1995). Where deviations from the standards occur, the information is fed back while the inputs, as well as the production and service processes, are aligned to meet predetermined standards (Simons 1995).

Interactive control systems are formal information systems used by managers to regularly and personally intervene in subordinates' decision-making behaviour (Simons 1995). These systems are used to encourage learning in the organisation and generate new ideas and strategies (Simons 1995). The aim of these systems is to manage strategic uncertainty (opportunities and threats) through repeated dialogue and meetings between top management and managers and between managers and subordinates in the bid to identify new business opportunities while modifying or changing organisational strategy.

This study discusses cases of the promotion of gender equality using MCSs based on diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems. This is because the degree of use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems MCSs is related to the integration of gender equality into organisational strategy (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012; Wijethilake and Upadhaya 2020). Explaining how and why multiple elements relate to or complement each other based on typology leads to the theorisation of ideal MCS configurations for integrating gender equality into organisational strategy (Doty and Glick 1994; Miller 1996). Gond et al. (2012) presented a typology to identify the shift from one MCS configuration to another based on the degree of integration between sustainability and organisational strategy in terms of the use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems. Based on the theoretical framework of Gond et al. (2012), this study depicts the degree of integration of gender equality and organisational strategy according to each MCS configuration.

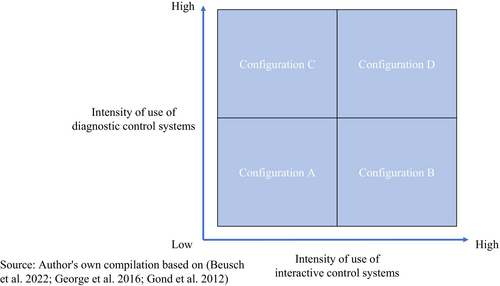

According to Nagano and Hosoda (2023), the following four MCS configurations can be envisaged depending on how MCSs are utilised (Figure 1). Depending on the configuration, the degree of integration between the realisation of gender equality and strategy will differ (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012).

Configuration A: In situations where neither diagnostic control systems nor interactive control systems are used to realise gender equality, companies are not in a state of strategic commitment to realise gender equality (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012). In this situation, the necessary systems for realising gender equality have not been identified and measures to increase the number of female managers remain unclear. Thus, there has yet to emerge a system for realising gender equality based on information on the development status of female managers (Nagano and Hosoda 2023).

Configuration B: The degree of use of interactive control systems increases in the initial stages of developing various systems to realise gender equality (Nagano and Hosoda 2023). It is necessary to gather the opinions of human resource (HR) managers and workplaces on what systems need to be implemented, even as top management must make decisions based on these opinions (Nagano and Hosoda 2023).

Configuration C: In the process of developing various systems to realise gender equality, there is an increase in the degree to which the ratio of female managers is set as a target related to gender equality in diagnostic control systems, even as progress is managed (Nagano and Hosoda 2023). By managing progress, diagnostic control systems provide material for discussion to strategically improve the prevalent state of gender equality (Nagano and Hosoda 2023).

Configuration D: This is a situation with a high degree of use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems to achieve gender equality. In this configuration, as well as motivating managers involved in the realisation of gender equality to achieve their goals, managers also attempt to strategically deliver gender equality through necessary discussions to achieve their goals (Nagano and Hosoda 2023).

The integration of gender equality into organisational strategy should be considered from three dimensions: technical, organisational and cognitive. These three dimensions are complementary and influence the degree of use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems, as well as changes in the configuration of MCSs. Consequently, technical, organisational and cognitive integration influences the degree of integration into organisational strategy for realising gender equality (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012).

Technical integration focuses on the technical dimension, which is necessary for promoting gender equality as a strategic issue (Gond et al. 2012). Technical integration supports integrating gender equality into MCSs by collecting and using data related to gender equality (Gond et al. 2012). Without technical integration, diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems cannot work towards realising gender equality (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012).

Organisational integration seeks to capture the dimensions of integrating gender equality into organisational strategy through ‘actors' practices’ (Gond et al. 2012, p. 206). Actors' practices are what people from different layers or/and departments do (Gond et al. 2012). Such practices are believed to influence the operation of systems and measures to achieve the goals and the degree to which the goals are achieved (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012).

Cognitive integration focuses on how people's thinking and beliefs change towards the realisation of gender equality. The more people understand the need to achieve gender equality, the more they are encouraged to operationalise the institutions and measures necessary for achieving it. In addition, interactive communication for proposing and improving institutions and measures to realise gender equality will be activated within organisations (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012).

Based on the framework, this research investigates the configuration of MCSs and assesses the three dimensions to reveal the extent to which the realisation of gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy in Japanese companies.

4 Methodology

This study investigated the degree to which the realisation of gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy depending on the configuration of MCSs, using case studies of seven Japanese companies. The case study is a research method involving detailed descriptions and analyses of one or more cases (Creswell and Poth 2016). The approach allows us to evaluate MCS configurations for promoting gender equality (Beusch et al. 2022; George et al. 2016; Gond et al. 2012). A case-study approach involving multiple entities is more appropriate for examining the replication of findings and determining whether they can be duplicated (Yin 2018). Multiple case studies, in which individual cases are analysed and compared, can be used to identify commonalities and differences in the use of MCSs in the integration of gender equality and organisational strategy (Creswell and Poth 2016; Yin 2018). The case studies used multiple sources of data, but focused mainly on interview transcriptions.

To confirm the results of the analysis, the authors consulted company websites, publicly available information about the companies and documents provided by the interviewees. The case companies were those that had been or were currently included in the ‘Nadeshiko Brands’ several times. Nadeshiko Brands are companies selected by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) as outstanding organisations among Japanese listed companies in terms of their promotion of gender equality. The selection of companies for Nadeshiko Brands means that companies that are actively committed to gender equality are attractive investment targets for investors who value medium- and long-term improvements in corporate value. The announcement of Nadeshiko Brands by METI and TSE is also aimed at further increasing investors' interest in such companies and accelerating listed companies' efforts to promote gender equality (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry 2023). This study aims to clarify how gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy through the use of MCSs, targeting Japanese companies that have experienced recognition by third-party organisations such as METI and TSE for their proactive efforts towards gender equality. The interviewees and interview summaries are shown in Table 1.

| Company | Industry | Employees | Interviewee | Interviewer | Length and date of interview | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Foodstuff manufacturing | 40,000 | Diversity promotion officer | All authors | 57 min. 05/08/2022 (Online) | Company A is a major Japanese food company dealing in beverages and food products globally. |

| Diversity promotion Manager | Second and third authors | 53 min. 20/12/2022 (Face to face) | ||||

| Diversity promotion officer | ||||||

| B | Land transport | 23,000 | Diversity promotion officer | All authors | 1h18min. 28/03/2023 (Online) | Company B is a company dealing with electric railways and real estate, mainly in the Tokyo metropolitan area. |

| C | Information and communications industry | 15,000 | Diversity promotion officer | All authors | 1h13min. 29/03/2023 (Online) | Company C is a leading Japanese systems integrator and provider of various IT solutions, including consulting and systems development. |

| D | Textile manufacturing | 22,000 | Diversity promotion Manager | All authors |

1h22min. 05/04/2023 (Face to face) |

Company D is a former textile manufacturing company that now manufactures ethical pharmaceuticals and home medical equipment. |

| Diversity promotion officer | ||||||

| E | Pharmaceutical manufacturing | 7000 | Diversity promotion Manager | First and second authors |

1h01min. 17/04/2023 (Face to face) |

Company E is a pharmaceutical manufacturing company with strong R&D in biopharmaceuticals. |

| Diversity promotion officer | ||||||

| F | Insurance | 49,000 | Chief Internal auditor | First and second authors |

1h37min. 29/05/2023 (Face to face) |

Company F is one of the largest insurance agencies in Japan, providing life and other insurance services, with service offices throughout Japan. |

| G | Foodstuff manufacturing | 30,000 | Diversity promotion officer | E-mail exchange only |

E-mail. 09/03/2023 24/03/2023 |

Company G is a leading Japanese food company with a global beverage and food product portfolio. |

- Source: Author's creation.

The analysis was conducted as follows. The first and second authors coded the interview comments to generate themes by reading the interview data repeatedly (Creswell and Poth 2016). The coding process was conducted in accordance with the framework of MCS configurations for integrating gender equality into organisational strategy and other related aspects, including the background, challenges, and outcomes of promoting gender equality. The use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems to realise gender equality, alongside the issue of technical, organisational and cognitive integration, produced themes based on the theoretical framework. The background and challenges of promoting gender equality were also extracted as themes. Thereafter, all the authors interpreted the study results for the individual cases and then compared the companies' performances using an aggregation table (Creswell and Poth 2016; Yin 2018).

5 Findings

Following the information in Tables 2 and 3, this section discusses the findings from the seven case studies. Table 2 shows how each company used diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems to achieve gender equality. Table 3 presents the three dimensions that integrate gender equality into organisational strategy.

| Company | Diagnostic use of MCSs | Interactive use of MCSs |

|---|---|---|

| A |

|

|

| B |

|

|

| C |

|

|

| D |

|

|

| E |

|

|

| F |

|

|

| G |

|

|

- Source: Author's own compilation based on the findings.

| Company | Technical integration | Organisational integration | Cognitive integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| A |

|

|

|

| B |

|

|

|

| C |

|

|

|

| D |

|

|

|

| E |

|

|

|

| F |

|

|

|

| G |

|

|

|

- Source: Author's own compilation based on the findings.

5.1 Organisational Integration and Interactive Control Systems at the Initial Stage of Promoting Gender Equality

Organisational integration was initially facilitated by the establishment of departments or project teams aimed at promoting gender equality throughout the entire company. At the initial stage of promoting gender equality, there were no systems in place to facilitate ease of work, training and other forms of professional development or training programmes for managers tasked with driving the implementation of gender equality. In this situation, communication among top management, as well as between top management and HR managers, was implemented to kick-start the promotion of gender equality in the seven companies. Moreover, as illustrated in Table 2, the department or project team conducted surveys with top management and employees to develop a system for promoting gender equality in companies B, C, E, F and G. Consequently, organisational integration was encouraged as a means of advancing gender equality.

In the case of A, regarding the background to promoting women's empowerment, the initially established Diversity Promotion Office addressed issues of gender, nationality, disability and age in four key areas. Focusing particularly on women, the 2011 declaration on diversity management was the start of initiatives for achieving gender equality. Since this declaration on diversity promotion, the Diversity Promotion Office has been established and initiatives to promote work style reform were outlined. Systems have been developed mainly to support balancing work and family life with a view to reducing the number of employees leaving the workforce due to childcare reasons and encouraging women to achieve their career potential.

Because of increases in the number of women and people balancing work and childcare, as well as the growing social emphasis on balancing family and work, Company B has been working on reforming the way people work while also promoting the creation of a comfortable working environment since the early 2000s. From 2010, it has also been focusing on promoting diversity management, including the promotion of gender equality. A Diversity Working Group was established in 2013, followed by a dedicated team for diversity promotion in 2014. Various other initiatives have also been planned and implemented.

Company C launched a limited six-month women's advancement project under the direct control of the president; it also conducted an interview survey of all female employees in 2006 because the president was alarmed by the fact that there were few women and the turnover rate among women was high. The results of the interviews revealed issues faced by women who continue to work. To address these issues the company improved its systems, focusing on support for work–life balance.

In Company D, the CEO, who assumed office in 1999, took a top-down approach to the promotion of gender equality. That CEO operated on the assumption that making it easier for women to work is important for all employees and that promoting women's active participation is necessary for the achievement of global competitiveness. Company D started the Office for the Promotion of Women's Advancement as a full-time organisation in 2000.

In 2010, Company E assembled a team comprising female representatives from each department to discuss issues related to promoting gender equality. From 2005 to 2007, there had been an increase in new graduate hiring, with both men and women recruited, particularly for the position of medical representative (MR). Activities were developed to create a gender-neutral environment in which men and women could work longer and earn promotion to important decision-making positions.

Regarding Company F, a project team was established in the HR department in 2002 to enable women to continue working after marriage or childbirth. In the same year, project team members set up a volunteer-run Women's Committee to aggregate women's observations and use them in new initiatives. In 2003, a dedicated gender equality unit was established in the HR department. The unit worked with the Women's Committee to improve the support system for combining work and childbirth/childcare, as well as to enhance employees' career awareness.

In Company G, to address the high turnover rate and low motivation of female employees, top management in 2006 initiated messaging that led to the emergence of the women's advancement network comprised by women. It was an opportunity to gather views on the systems needed to create a more women-friendly working environment. Right from the beginning, top management has been committed to achieving gender equality, leading to the emergence of systems to improve the working environment. In the late 2000s, gender-neutral work assignments began to be made and the evaluation of women's work and competence within the company improved. However, it is also true that many lower level managers were not committed to realising gender equality.

5.2 The Use of Diagnostic Control Systems and Technical Integration

Following the development of systems for the realisation of gender equality, a ratio of female managers to the total number of managers was established for all companies (see Table 2). To set and manage these targets, it was necessary to manage individual information in the system. As a result of high levels of technical integration, all companies were able to manage individual information and calculate the ratio of female managers.

At Company A, the rate of female employees returning to work after parental leave reached 100% in 2018, thus further accelerating the promotion of gender equality. The target of a ‘30% female management ratio by 2030’ was set in 2019 and announced in 2020. In Company A, top management and HR personnel are able to discuss achieving gender equality and the management board continually discusses achieving gender equality in its diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) discussions. Although the achievement of targets was monitored at management meetings, it took some time for each manager to fully commit to them in their own key performance indicators (KPIs).

In Company B, target figures for the number of female managers (section manager level) were set and diversity management was specified in the medium-term management plan of 2015.

Regarding Company C, in 2012, a target number of female managers (section managers and above) was set to be achieved by 2018. This target remained unchanged until it was achieved in 2019. In addition to setting and managing targets, top management, officers and frontline managers discussed progress at board meetings. Top management and HR communicate regularly to discuss HR strategy and other issues needed to achieve gender equality.

In Company D, the ratio of new female graduates hired was 10% in 1999. Based on the idea that a minority composition ratio of 30% or more was necessary to revitalise the organisation, top management set a 30% hiring ratio target for new female graduates. Their sustained commitment has contributed to maintaining this ratio above 30% since 2001.

In Company E, since 2015, companywide KPIs for promoting gender equality (2015–2018) have been established. In 2019, with the aim of further accelerating promotion, the company set KPIs for each department, in addition to companywide KPIs. A new personnel system was also introduced to realise competency-based treatment that was not tied to attributes.

In Company F, a companywide target of 30% women in management positions (section managers and above) was set in 2013. In the course of monitoring progress, issues were identified, such as the fact that achievement status differed depending on the department and job type. The number of female managers in internal departments, where they work at the head office and do not change jobs, was relatively high. However, the number of female managers in sales departments, where they are repeatedly transferred to different regions and must continue to demonstrate their abilities in line with the characteristics of each region, was relatively low.

In Company G, a long-term plan for the promotion of gender equality and diversity was formulated, and a department for the promotion of diversity, including gender equality, was established in 2013. In addition, Company G has a career development policy for women from the early stages of their career development that is currently being implemented in the workplace. In Japan, efforts are being made to achieve the target of 30% female managers and 30% female directors in holding companies.

5.3 The Use of Interactive Control Systems Towards the Integration of Gender Equality into Organisational Strategy

The use of diagnostic control systems in all companies has led to discussions on the advancement of gender equality both within top management and between HR managers and top management (see Table 2). These communication processes have been conducted regularly and have functioned as interactive control systems, with the input of information from diagnostic control systems.

In Company A, top management and HR personnel are able to discuss achieving gender equality and the management board continually discusses achieving gender equality in its DEI discussions. Although the achievement of targets was monitored at management meetings, it took a while for each manager to fully commit to them in their KPIs.

In Company B, a new advisory board on HR strategy has been established to report and exchange views on the progress of diversity management. Diversity management, including the promotion of gender equality, is addressed throughout the organisation with the establishment of this advisory board.

In Company C, top management, officers and frontline managers discuss progress at board meetings. Top management and HR communicate regularly to discuss HR strategy and other issues needed to achieve gender equality.

In Company D, discussions on the realisation of gender equality have been held at various meetings to achieve these targets. For example, there is a management strategy meeting among top management, as well as a group HR diversity and inclusion (D&I) meeting and a diversity promotion committee that includes managers responsible for HR in group companies. In addition, working groups and project teams discussed the realisation of gender equality. Not only successive generations of top management but also middle management and people in the workplace have a high level of understanding and commitment to gender equality and a good understanding of diversity.

In Company E, a conference for the promotion of gender equality was held, attended by management directors, including the president and heads of departments. They reviewed progress for the year and discussed issues related to the promotion of women. By enhancing the accuracy of progress reviews in this manner, the company can identify female employees as candidates for management positions and subsequently monitor their promotion and steady development. In addition, the management, the upper management and those in charge shared a common understanding of issues regarding the realisation of gender equality.

In Company F, once a year, a D&I Promotion Headquarters meeting involving the presidents of the Group companies is held. At the meeting, the entire management team promotes D&I in the Group intending to realise ‘Diversity for Growth’. In addition, there are opportunities for the internal audit department and top management to exchange views on how HR development is being conducted at each sales office.

In Company G, since 2020, the promotion of gender equality has been a regular agenda item for the Board of Directors, with monitoring being strengthened. Top management and the organisation as a whole have successfully communicated the need to realise gender equality and the understanding of general and plant managers now aligns with the ideas of top management.

5.4 Improvements in Diagnostic Control Systems and Continuous Technical Integration

In the further course of the initiatives, interactive control systems based on information from diagnostic control systems were being used within the companies, with some companies improving their diagnostic control systems through discussions. For example, the lack of female managers has led to an emphasis on the setting of targets based on the company's situation (Company B, C and D) (see Table 2).

In Company B, the targets for female managers were achieved one year ahead of schedule. Subsequently, in the bid to create an environment in which more people can play active roles, further targets were set for the ratio of female managers and the percentage of male employees taking parental leave.

In Company C, after achieving the target for the development of female managers (section managers and above), from 2021, targets were set for the ratio of female department managers and the number of highly specialised female engineers. This was to increase the number of female managers at the top level, while simultaneously enabling women to pursue diverse careers. These targets are positioned as management goals, with a system being put in place to motivate everyone from top to middle management to take individual development seriously and achieve these targets.

In 2020–2022, Company D set the KPIs to promote diversity in the executive ranks, with regional strategies and KPIs being set according to the situation in each region, not only in Japan but also globally, even as measures were implemented to achieve the goals. In 2023, a long-term target of at least 30% female and non-Japanese officers was set for 2030. Furthermore, to grow the list of female executive candidates, targets for female section managers and above were set for each business and linked to executive remuneration. These initiatives have been implemented not only in Japan but also globally.

Companies A, E and F also enhanced technical integration to develop female managers individually and to achieve the targets (see Table 3). In Company A, a development plan for female managers for the next three to four years was put in place on a nomination basis, with managers in the workplace developing the relevant candidates under the development plan. The HR department proposed these targets to the management board, which approved them. In Company E, a talent management system was also used both to develop managers and to formulate and implement an HR development plan based on individual ability and aptitude.

5.5 Continuous Organisational Integration

Organisational integration was continuously enhanced by actors from different layers and departments, with the objective of incorporating gender equality into organisational strategy. As shown in Table 3, all companies continuously address issues hindering achievement of the aforementioned targets through the implementation of various systems led by the HR departments and specialised offices to promote gender equality. Top management has also persistently supported the implementation of various systems for promoting gender equality by the use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems; top management has also been consistent in conveying the importance of promoting gender equality in all companies. Upper–lower level managers also contributed to support the use of various systems and the development of female employees in six companies (Company A, B, C, E, F and G).

In Company A, the performance measurement system has been reviewed to ensure that employees can be promoted regardless of life events. Efforts have been made to ensure that absence during maternity or paternity leave does not affect performance appraisals and that employees are appraised on performance if they meet standard attendance rates. To realise gender equality in the workplace, the top management of each operating company and frontline managers work together to support the career development of female employees and foster a culture of gender equality under the basic policy. Training and workshops for managers were conducted to promote these initiatives. In addition, senior managers have contributed to the establishment of development plans for nominated female managers and for the creation of a climate that is conducive to gender equality. Messages related to the realisation of gender equality have been disseminated by top management as a DEI issue. In particular, the current chief executive officer (CEO) has sent messages on the importance of DEI. In 2021, a DEI workshop for executives, including top management, was held and an individual DEI programme was implemented in 2023.

Company B promotes diversity management from three perspectives: systems, climate and mindset. Regarding systems, in addition to the hourly paid leave, the return-to-workplace system and the childcare leave that had been in place long before 2010, various other policies have been implemented to enable employees to continue working after life events. Among these policies are teleworking (including telecommuting) and the establishment of shorter hours and days of work. On climate, diversity seminars have been held for all officers and employees every year since 2015. In 2017, ‘fostering an organisational climate’ was included as an evaluation item for managers, given that they contribute to promote gender equality in the workplace. Messages on achieving gender equality have also been disseminated by top management, who have also appointed female managers to senior positions, such as president of a subsidiary. This helps to create a climate in which women can play an active role. Regarding mindset, the company has been organising seminars for women and sending female employees to external training courses with a view to boosting their morale and further motivating them.

In Company C, as women continued to work, a dedicated diversity promotion organisation was established in 2012, leading to the launching of the next stage of gender-equality initiatives. During this period, a system was also designed whereby male senior managers acted as mentors to train female managers to become senior managers. In the workplace, line managers support female employees to think about acquiring management skills and career development. Top management personally provided messages on gender equality during the training. There is also a high level of understanding and action on the part of management and board members towards the realisation of gender equality, as exemplified by discussions at board meetings.

In Company D, the mission of the Women's Advancement Office was expanded and it became the Diversity Promotion Office, with various systems put in place, including hourly paid leave, childcare leave and teleworking in 2007. In 2011, the company began training female candidates for management positions. To encourage the realisation of gender equality in the workplace, diversity-related training was provided to all employee levels. In addition, to ensure that female employees received fair and impartial evaluations regardless of life events, Company D established a system that avoids promotion delays due to life events such as childbirth and childcare. This has enabled the company to promote the career growth of employees returning from maternity and childcare leave. Managers are responsible for the development of subordinates regardless of gender. They also receive training on gender equality in the workplace as part of their new manager training. However, as only 20% of the employees in Company D are female, there is a limited number of managers with female subordinates. Successive top management sent messages to ensure that those initiatives steadily led to the realisation of gender equality.

In Company E, the Diversity Promotion Office was established in 2012 to expand the scope of its activities. Initially, each headquarters had an officer who handled issues of diversity promotion, with initiatives developed in line with the issues faced by each department. The promotion of gender equality was discussed and implemented in collaboration with divisions on matters specific to each headquarters. Company E also introduced, reviewed and promoted the use of systems to support the balance between work and family life. The company emphasised the linkage between diversity and such talent management systems and worked to promote the success of diverse workers, including female employees. The CEO disseminated messages to members of the organisation on the importance of diversity and inclusion and the promotion of gender equality. Female managerial candidates were also assessed and developed within the talent management system as a way to steadily develop and promote them. From 2019, in cooperation with the HR Business Partners (HRBPs) assigned to each department, female manager candidates were identified, individual development plans were set and training and promotion were promoted. HRBPs ensure that HR strategy is implemented within departments.

From around 2010, Company F, in its bid to steadily promote the career advancement of women, made it possible for women to choose whether to be transferred to a new location and it also abolished the course-based employment management system that is unique to Japanese financial institutions. Since 2011, female managers have been selected for various training programmes. The creation of a comfortable working environment for women, as well as the promotion of the system, has created a comfortable working environment for men, too. To support these efforts, the company communicated the importance of diversity and gender equality under the President of Holdings from 2015 onwards. In addition, the top management was involved in the development of female managers in some systems and tried to promote female employees to senior management positions. Workplace managers were also committed to the development of female managers and implemented individually planned development. Unconscious bias training was also conducted to raise managerial awareness. In 2017, from the viewpoint that it was no longer necessary to give special treatment only to women, the company increased opportunities to provide the same training regardless of gender. Subsequently, from 2022, training limited to women was abolished altogether.

In company G, top management's strong commitment to achieving gender equality has led to the development of systems to improve the working environment. In the late 2000s, gender-neutral work assignments began to be made and the evaluation of women's work and competence within the company improved. However, it is also true that many lower level managers were not committed to realising gender equality. Company G has a career development policy for women from the early stages of their career development. In addition, since 2022, an evaluation system has been initiated in which the period of childcare leave does not negatively affect the personnel evaluation process, leading to increased motivation among employees after they return from maternity leave. Top management and the organisation as a whole have been successful in strongly communicating the need to realise gender equality, with the understanding of general and plant managers now aligned with top management's ideas.

5.6 Gradual Changes in Cognitive Integration

At the initial stage in the drive for gender equality, cognitive integration was weak because top management and managers did not fully appreciate the importance of gender equality. However, all companies set targets to increase the number of female managers while committing to improving the work environment for both men and women. Formal discussions on the realisation of gender equality have been conducted on a regular basis, based on information from diagnostic control systems. Consequently, cognitive integration became high. As illustrated in Table 3, more top management and managers have emerged who are aware of the importance of gender equality and are working towards meeting targets for increased numbers of female managers.

In Company A, until around 2015–2016, it was difficult to communicate the need to promote gender equality in the workplace. Although the achievement of targets was monitored at management meetings, managers did not immediately commit fully to those targets in their own KPIs. Through the ongoing use of interactive control systems, top management's understanding of and commitment to the realisation of gender equality has stayed high.

Company B did not have a high level of awareness of diversity management from the outset, but the management was aware of the issues. The company has made steady efforts in the three aspects of system, climate and mindset in a well-balanced manner, thereby creating a comfortable working environment for both women and men. This situation has accelerated efforts towards the realisation of diversity management, including gender equality.

In Company C, successive top management teams have expressed interest in achieving gender equality, about which there is now better understanding in the workplace. There is also a high level of understanding and action on the part of management and board members with regard to the realisation of gender equality, as shown by discussions at board meetings. Workplace supervisors have also made significant contributions to management training on the realisation of gender equality. Consequently, women continue to work in the workplace both as a matter of course and to improve the way they work. Furthermore, the creation of an environment in which there are women in line positions has made it easier to work, in addition to creating a workplace where it is commonplace for women to aim for management positions.

In Company D, not only successive generations of top management but also middle management and people in the workplace have a high level of understanding and commitment to gender equality, as well as a good understanding of diversity. Organisational efforts to realise gender equality have created a good working environment for both women and men. Consequently, discussions have been generated on achieving and targeting goals for the realisation of gender equality and creating better workplaces.

In Company E, one of their strengths is their high level of understanding of the importance of D&I and the promotion of gender equality among the management board and upper management. This is expected to ensure that diverse employees, regardless of gender, will continue to be appropriately recruited for important decision-making in the future.

In Company F, top management messages and various training programmes have helped to deepen understanding of gender equality in the workplace. Gender equality is now taken for granted throughout the organisation. Initiatives are being implemented to promote gender equality, such as the abolition of women-only training courses.

In Company G, men's understanding has improved and the working environment become more comfortable for women, even as women have also been contributing to the production of managerial results. This situation is due to the inclusion of gender equality progress management in the Board's regular agenda (2020) and the development of a long-term plan with targets for 2030 (2022).

6 Discussion

Despite efforts by government and companies in Japan, the objective of attaining 30% of women in leadership positions by 2020 has not yet been realised. Consequently, there is a strong need for the development of initiatives for increasing the number of women who move from lower management positions to senior positions (Cabinet Office 2021). Furthermore, as Japan's working population continues to decline in line with its rapidly ageing population and declining birth rate, Japanese companies are required to take action to mitigate the gender gap and promote gender equality in order to secure employees (Cabinet Office 2021). From a strategic perspective, MCSs have the potential to facilitate the establishment and achievement of the objective of transforming companies to address gender inequality as a sustainability issue (Burritt et al. 2023; Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Schaltegger et al. 2022). Focusing the analysis on MCS configurations can also help in exploring the relationship between MCSs usage and influencing factors—a situation that is necessary for interpreting the relationships between MCSs and integration of gender equality into organisational strategy (Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024). As such, this research examined MCS configurations to promote gender equality and lead to more effective management of the process of achieving gender equality within organisations, based on case studies of seven Japanese companies.

Based on the findings of the seven companies, the following describes how MCSs have been configured and how gender equality has been integrated into organisational strategy, depending on the extent to which the MCSs have been utilised. In the initial stage of realising gender equality, MCSs were not fully utilised; therefore, the realisation of gender equality was not integrated into organisational strategy (Configuration A). At this stage, there are no systems related to ease of work, training and other development systems or training systems for managers responsible for the realisation of gender equality (Nagano and Hosoda 2023).

Subsequently, communication among top management and between top management and HR managers was implemented in the seven companies. Moreover, the five companies (Company A, B, C, D and E) formed project teams with the objective of developing systems for incorporating the opinions and suggestions of frontline employees. At this stage, the degree of integration between the realisation of gender equality and organisational strategy remained low because the focus was on the development of various systems to realise gender equality (Configuration B).

In terms of organisational integration for the realisation of gender equality in Configuration B, specialised offices to promote gender equality were established in the seven companies. In all companies, top management supported the implementation of various systems promoting gender equality (Beusch et al.2022; Gond et al. 2012). However, cognitive integration at this stage was low, as top management and upper-/lower level managers did not always understand the significance of gender equality (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012).

Moreover, when or after the systems for the realisation of gender equality were developed, the seven companies set targets related to the promotion of women to management positions and started to use diagnostic control systems. At this stage, the realisation of gender equality and its integration with organisational strategy progressed (Configuration C), just as efforts towards the development of female managers began in earnest. In Configuration C, through diagnostic control systems, planning and current assessment for the realisation of gender equality became possible (Nagano and Hosoda 2023). Simultaneously, as an interactive control system, the promotion of gender equality was discussed at management meetings based on information from diagnostic control systems.

Technical integration was already at a high level as targets for the development of female managers were set and managed throughout the company. However, Companies A, E and F further enhanced technical integration. Companies A and F use a nomination-based approach to effectively develop female managers, while Company E uses a talent management system to make training more effective.

Organisational integration gradually increased owing to the involvement of top management and the actions of upper-/lower level managers regarding the realisation of gender equality in Configuration C (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012). The use of various systems introduced by the HR and the specialised offices to promote gender equality and the development of female employees have been promoted in earnest in the workplace.

Regarding cognitive integration in Configuration C, a certain number of managers had a good understanding of the realisation of gender equality but lacked action (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012). Female employees had to be motivated for promotion (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012). Therefore, in terms of organisational integration, the emphasis was on HR-led training for managers and female employees and messages from top management (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012).

The seven companies have recently achieved a high level of use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems to achieve gender equality, with the achievement of gender equality being highly integrated into their strategies (Configuration D). Gender-friendly workplaces and increased numbers of role models promote efforts to realise gender equality in the workplace and, consequently, increase the degree of integration between the realisation of gender equality and organisational strategy.

Regular discussions on the realisation of gender equality among top management as well as between top management and managers in formal settings, based on information from diagnostic control systems, have ensured that the realisation of gender equality is highly integrated into organisational strategy in Configuration D. These discussions help to establish the new initiatives (Nagano and Hosoda 2023), as there have been improvements in the diagnostic control systems of three companies (Company B, C and D). For example, the lack of female managers has led to an emphasis on the setting of targets based on the company's situation.

Efforts have also been made to further increase organisational and cognitive integration to blend the realisation of gender equality with organisational strategy in Configuration D (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012). In the seven companies, top management and HR managers are developing and improving various systems (Nagano and Hosoda 2023). Frontline managers are also working to create a workplace where the use of such systems and the presence of female managers are the norm in Company A, B, C, E, F and G (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012). Company D provides gender equality training as part of its new manager training programme. At Company D, managers are responsible for developing their subordinates regardless of gender, and they understand the importance of developing their subordinates in a gender-equal way. However, as only 20% of the company's employees are female, there are not many managers who actually have female subordinates.

Regarding cognitive integration in all the companies, the understanding of gender equality among top management, the heads of individual businesses and managers in the workplace is significant. This internal situation regarding the realisation of gender equality can be a factor that activates interactive communication within the organisation to propose and improve systems and measures for realising gender equality (Beusch et al. 2022; Gond et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, challenges remain in achieving gender equality. The small number of female managers is due to past recruitment systems. Diagnostic control systems need to manage both the ratio of female managers and the recruitment plans for women (Company A, B, D and E). There are also other issues that require continuous improvement in organisational and cognitive integration, such as unconscious bias among managers (Company B, C, E, F and G), turnover due to life events (Company E), female manager development varying according to the departmental job characteristics and departmental tradition (Company A, D and F) and a climate of satisfaction with the status quo (Company E). The excessive domestic burden on women in Japan has affected their attitudes to work (Company C). It should be noted that this is a problem that is difficult to solve through internal initiatives alone. To achieve gender equality, both companies and society need to change their values, hence the need for cooperation among stakeholders, including companies, governments and individuals (Kobayashi 2021; Kobayashi and Eweje 2021).

7 Contributions

This study describes the configurations of MCSs with a focus on the use of diagnostic control systems and interactive control systems. It also discusses the technical, organisational and cognitive dimensions of integration and assesses the degree of integration between gender equality and organisational strategy. The study makes several contributions to theory, practice and policy as highlighted below.

7.1 Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to advancements in management accounting and MCSs research. In particular, the study advances work on the configurations of MCSs that contribute to the integration of sustainability into organisational strategy (Beusch et al. 2022; Crutzen et al. 2017; Ditillo and Lisi 2016; George et al. 2016). The research has proposed a theoretical framework for elucidating the path to each configuration that can facilitate the transition of MCSs towards gender equality. This has led to the theorisation of ideal MCS configurations for integrating gender equality into organisational strategy. The theoretical focus on the configuration of MCSs according to their use supports meaningful progress in exploring the potential of MCSs as tools for strategically achieving gender equality.

This research also contributes to the body of literature on gender equality in the workplace. The current understanding of mechanisms to promote gender equality in managerial positions is limited. This study advances the discourse by proposing mechanisms to enhance gender equality, drawing on insights from management accounting and MCSs research.

7.2 Practical Contributions

This study also contributes to practice. Through a comparative analysis of the shifts in the configurations of MCSs in Japanese companies making serious efforts to promote gender equality, it has been possible to show the configuration of MCSs according to the degree of integration between the realisation of gender equality and organisational strategy. This also has the potential to facilitate more effective management of the process of achieving gender equality within organisations not only in Japan but also in other countries facing difficulties in promoting gender equality. Furthermore, while the MCS configurations are developed based on the cases of large listed Japanese companies, the configurations can also aid in promoting gender equality across organisations of various sizes, including small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This is particularly relevant, as SMEs are increasingly striving to integrate environmental and social considerations into their business strategies through the use of MCSs (Cavicchi, Oppi, and Vagnoni 2023; Hosoda 2018).

7.3 Policy Contributions

This study also carries implications for policymakers. The proposed theoretical framework can indicate the extent to which gender equality is promoted in organisations. Using this framework, policies that use each MCS configuration can help address gender inequality based on the needs of each organisation. The configuration of each MCS to promote gender equality as identified in this study can help change gender roles in the workplace and develop female leaders. Ultimately, this will support the government's goal of retaining women in the workforce and developing them for managerial roles.

In addition, in the case of Japan, given that 99.7% of Japanese companies are SMEs3 (The Small and Medium Enterprise Agency 2024), it is imperative to acknowledge the significance of MCS configurations in order to advance gender equality across SMEs in Japan. This is because SMEs are increasingly promoting women's participation in the workforce; however, only a limited proportion of these companies are actively engaged in such initiatives (Cabinet Office 2023). Consequently, policy development that considers adoption of the MCS configurations for SMEs will be essential for promoting gender equality throughout the nation.

8 Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research

In Japan, closing the gender gap has been identified as one of the most important sustainability issues of the age. In the field of management accounting and MCSs research on sustainability, the need for research on MCSs to close the gender gap has been identified (Burritt et al. 2023; Hosoda and Toyosaki 2024; Nagano and Hosoda 2023; Schaltegger et al. 2022). The focus on MCS configurations advances the exploration of the potential of MCSs as tools for strategically achieving gender equality. This is because the extent to which gender equality is integrated into organisational strategy varies according to the configuration of each MCS (Beusch et al. 2022; Ditillo and Lisi 2016; George et al. 2016; Ghosh et al. 2019; Gond et al. 2012).